Managing Tourist Destinations According to the Principles of the Social Economy: The Case of the Les Oiseaux de Passage Cooperative Platform

Abstract

1. Introduction

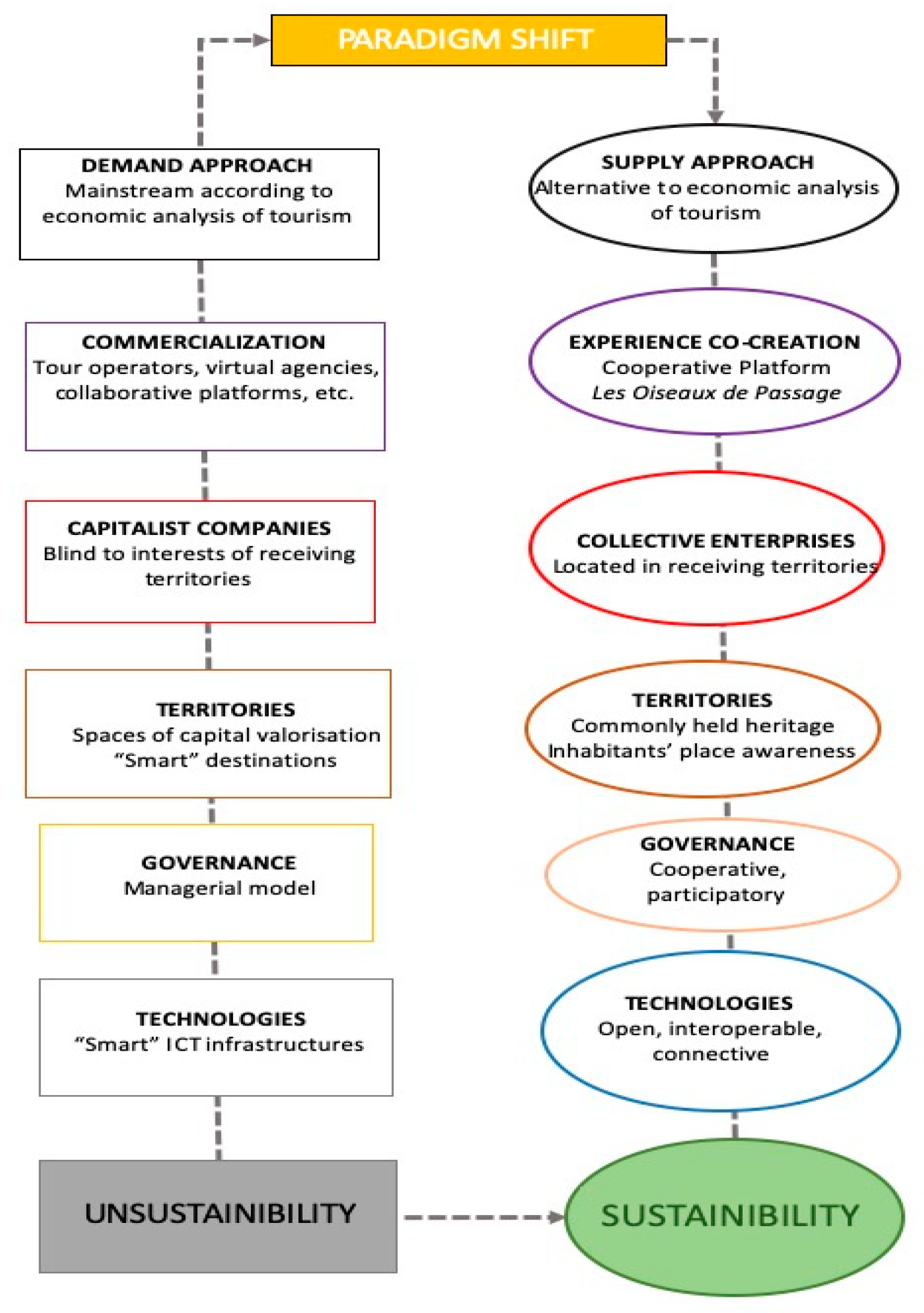

2. An Unsustainable Model: Sharing Platforms and the Management of Tourist Destinations

2.1. The Discourse of the Sharing Economy: The Truth Behind Airbnb’s Rhetoric

- In contrast to claims of disintermediation as a result of the collaborative practices of the digital economy, according to [24], not only are intermediaries not eliminated, but they take on unprecedented importance and power, which, due to the effects of the internet, display clear monopolistic tendencies.

- The platforms keep very strict control over the information that users can exchange in order to prevent any communication and ultimate economic transaction being conducted through alternative channels, going so far as to charge a commission of up to 20% of the published fee. In the view of [25], such platforms exercise an authoritarian control over what actions users can do on them.

- These players take on the role of producers of tourism, oriented towards demand, a role historically occupied by the large tour operators. In addition, they allow tourists themselves to participate in the configuration of the tourist products on offer, giving users the possibility to co-create them (in terms of organising and planning the outward and return journeys, for example). In this respect, they are genuine capitalist enterprises engaged in the production or facilitation of tourism products (experiences), and shaping them according to their own interests, in much the same way as the large tour operators have always done.

- Another much repeated claim of the collaborative consumption discourse is that it results in an even distribution of extra income for the hosts. Again, research suggests that this is true only for such individuals as are able to offer accommodation in properties where they are not resident—ranging from buy-to-let flats to second homes—and for whom the rental either wholly or partially constitutes their living. For example, according to [29], only 10.54% of rentals in Mallorca involve domiciles, that is with the owner and guest sharing space, with the remaining 89.46% involving rentals of the complete property. The conclusion to be drawn is that the vast majority of private rentals are by those with sufficient resources to rent out a property in which they are not resident for anything between several months to the whole year.

- Related to the above, another frequent complaint about collaborative platforms concerns the part they play in the so-called gentrification of over-subscribed areas. The effect is two-fold: the rental market reduces the housing stock available for residential purposes, while at the same time driving up the rents on what residential properties there are. The result, as described in sources [29] and [30], is that locals can no longer afford to live in their own town.

- A commonly occurring trope of the discourse is that of providing a quality experience, a new way of doing tourism radically different from traditional modes, which brings added value. Nevertheless, there is no getting away from the fact that the business model is low-cost, exploiting the possibilities offered by technology to enable the consumer to put together their own product and so reduce costs, but inevitably introducing job insecurity and impoverishment into the capitalist society, alongside high environmental costs [20].

- The trope of the quality alternative experience, in which, through the inclusivity of P2P, the tourist is transformed into a guest among the local residents, is also given the lie by the simple fact that, as reported by [20,29], in the majority of cases, the host is neither local nor resident, and the rental approximates a hotel more than a private residence, with the result that the tourist rarely fulfils the promise of participating in the local lifestyle.

- Finally, according to [23] (2019), platforms such as Airbnb have been lobbying European institutions over the last few years to make changes to the legislative framework of short-term lets that benefit their business model. These aspirations were articulated in the report “A European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy” [22], one of the key objectives of which was legitimise collaborative discourse in a document of political and symbolic significance.

2.2. The Need for a Destination-Driven Approach Focused on Supply. The Debate Around “Smart Destinations” and Their Governance

- the great variety of sectors and activities involved, which are located within the same territory and maintain important complementary interrelationships;

- the need to take into consideration both public and private stakeholders within an individual area, all of whom need to establish a cooperative matrix for the hospitality experience to work;

- the fact that, despite the involvement of all levels of public administration—state, regional, district and local—in the development of destinations, the ideal level for implementing tourism policies is that of district and/or local, as this is where the tourism actually takes place. This can be seen, for example, in the shifting emphasis of tourism policies in Spain, which according to [33], have seen increasing importance over time given to the local level;

- the need to provide visitors with a series of public and quasi-public goods and services—infrastructure, natural resources, sociocultural heritage, security, cleaning, etc.—which again are best managed collectively by stakeholders in situ (management of common goods and services);

- the phenomenon by which, as [34] notes, a territory not only represents the locus of tourist activity, but also an argument for the same, hence creating the need to balance its development against its conservation.

3. Methodology

4. The “Les Oiseaux de Passage” Platform: Cooperative Governance in Tourist Locations

4.1. The “Les Oiseaux de Passage” Platform

4.2. Characteristics of Cooperative Governance Applied to the “Les Oiseaux de Passage” Platform

5. Discussion

5.1. Territory as Commonly Held Heritage

5.2. Technology in the Service of Participative Relations between Humans

- Direct connection: the technological tool enables suppliers to promote the services and content they offer, authorising negotiation on a case by case basis. At the same time, by being based on annual subscriptions, it brings down the increasing costs of intermediaries (an average of 20% of the transaction on the large-scale platforms). This means that the costs of the platform are shared by and limited for the users.

- The technological tool also allows hosts and producers to present their offers in collaboration with their communities, as it is they themselves who best understand their location, while being able to cooperate at the same time with other destinations, thus conferring on the platform a dimension of cosmopolitan localism [69].

- Any aspect which might harm human contact and foment competition on the platform is forbidden, including for example a points system, certificates, classification systems and so on.

- Every content item (offers, stories) can be freely exported to other digital media (digital badges, interoperability). This free broadcasting of data allows everybody to fully express their identity within a multitude of digital media: travel blogs, social networks, personal sites, online press, associated platforms and so on. It can hence be concluded that the management of the destination stretches from the most local—the communities—to the most global—the worldwide broadcasters on social networks, blogs, online platforms, and so on.

- The ergonomics favours personalisation and co-production of content, and provides fluent and poetic navigation around the website. Each member of the platform has their own page on which to present themselves. Narration is based on a collaboration tool and a simplified editor (texts and images) to give free rein to everybody’s imagination while maintaining a common graphic identity. The travellers also have access to a simplified editor for sharing their impressions in visitor books and leaving testimony of their travel experiences.

- Disintermediation: facilitating direct interaction and interchange between hosts and visitors.

- Deautomation: facilitating negotiation between both parties considering the social, environmental and economic contexts at the moment of exchange.

- Destandardisation: facilitating the personalisation of experience and increased integration of the visitor in the local host space.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Tourism Organization. Las Cifras de Turistas Internacionales Podrían Caer Entre un 60.80% en 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/2AVLi9v (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Cals Güell, J. Turismo y Política Turística en España: Una Aproximación; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Figuerola, M. Turismo de masa y sociología: El caso español. Travel Res. 1976, 14, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. International Recommendations on Tourism Statistics; Methodological studies Série M N ° 83/Rev.1; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Environmental Outlook; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Economic Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, M.; Biggs, R.; Pereira, L.; Preiser, R.; Hichert, T.; Blanchard, R.; Warrington-Coetzee, H.; King, N.; Merrie, A.; Nilsson, W.; et al. Scenarios of Good Anthropocenes in Southern Africa. Futures 2020, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.M.; Seligman, M.E.P. Positive organizational Studies: Lesson from positive psychology. In Positive Organizational Scholarship, 1st ed.; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA; Available online: https://bit.ly/36qPJVs (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, L.; Bergeron, F. Global Distribution Systems: A Field Study of Their Use and Advantages in Travel Agencies. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 1997, 5, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Chen, J.S.; Uysal, M. Creating Experience Value in Tourism; CABI: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Ruiz, D. Manual de Gestión de Destinos Turísticos, 1st ed.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, M. Histoire du Tourisme de Masse, 1st ed.; Presses Universitaire de France: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cousin, S.; Réau, B. L’avènement du tourisme de masse. Les Grands Dossiers des Sciences Humaines 2011, 22, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Caire, G.A. Qui profitent les vacances? Le Monde diplomatique 2012, 700, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, P.J. Alineation, exploitation, and social media. Am. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. La Sociedad de Coste Marginal Cero: El Internet de las Cosas, el Procomún Colaborativo y el Eclipse del Capitalismo, 1st ed.; Planeta Group: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R.; y Rogers, R. What’s Mine is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live, 1st ed.; Collins: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J. Cambios en la producción y el consumo del turismo El caso de airbnb. In Turistificación Global, 1st ed.; Cañada, E., Murray, I., Eds.; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 325–432. [Google Scholar]

- Airbnb. Impacto Económico de Airnb en Barcelona y Cataluña, Airbnb, 2014. Available online: https://bit.ly/2yxecvS (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Comisión Europea. Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo, en el Consejo, al Comité Económico y Social Europeo y al Comité de las Regiones. Una Agenda Europea para la Economía Colaborativa, COM (2016) 356 Final. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gfiDwc (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Quaglieri-Domíngez, A.; Sánchez-Bergara, S. Alojamiento turístico y “economía colaborativa”: Una revisión crítica de los discursos y las respuestas normativas. In Turistificación Global, 1st ed.; Cañada, E., Murray, I., Eds.; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 343–365. [Google Scholar]

- Srnicek, N. Plataform Capitalism, 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambrige, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan, M.; Choe, J. Airbnb and cultural capitalism: Enclosure and control within the sharing economy. Anatolia Int. J. Hosp. Res. 2017, 28, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Sans, A.; Quaglieri Domínguez, A. Unravelling Airbnb: Urban Perspectives from Barcelona. In Reinventing the Local in Tourism: Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place, 1st ed.; Russo, A.P., Richards, G., Eds.; Paperbackshop UK Import: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Morales, A.; Mayorga-Toledano, M. New acommodation models in city tourism. The Case of Airbnb in Málaga, 2018. In Proceedings of the III Spring Symposium on Challenges in Tourism Development, Gran Canaria Island, Spain, 7–8 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dudas, G.; Vida, G.; Kovalcsik, T.; Boros, L. A socio-economic analisis of Airbnb in New York City. Reg. Stud. 2017, 7, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yrigoy, I. Airbnb en Menorca: ¿una nueva forma de gentrificación turística?: Localización de la vivienda turística, agentes e impactos sobre el alquiler residencial. Scr. Nova 2017, XXI, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Gago, A. Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon. Econ. Space 2019, 0, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de Escalona, F. El Turismo Explicado con Claridad, 1st ed.; PublishrLibrosEnRed: Madrid, Spain, 2003; Available online: www.librosenred.com (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Barroso-González, M.O.; Flores-Ruiz, D. La política turística como parte de la política económica. Revista de Análisis Turístico 2007, 4, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ruiz, D.; Barroso-González, M.O. Una revisión de la política turística española: Pasado, presente y retos de futuro. Papers de Turisme 2009, 46, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Rebollo, F. Análisis Territorial del Turismo; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1997; Volume 469. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, J.B. Sistemas de recomendación de servicios turísticos personalizados en el destino turístico inteligente. In Máster Universitario en Dirección y Planificación del Turismo; Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://bit.ly/3gfiDwc (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- López de Ávila, A.; García Sánchez, S. Destinos turísticos inteligentes. Harv. Deusto Bus. Rev. 2013, 224, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Girardot, J.J. Intelligence territoriale. In Activites et Perspectives de la CAENTI; CAENTI: Besanson, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ruiz, D.; Perogil-Burgos, J.; Miedes-Ugarte, B. Destinos turísticos inteligentes o territorios inteligentes? Estudios de casos en España. Estud. Reg. 2018, 113, 193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Perogil-Burgos, J. Turismo solidario y turismo responsable, aproximación a su marco teórico y conexiones con la inteligencia turística. Revista Iberoamericana de Economía Solidaria e Innovación Socioecológica 2018, 1, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S. Inteligencia Territorial y la Observación Colectiva. Rev. Espac. 2014, 4, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzano, H. Inteligencia Territorial. Teoría, Métodos e Iniciativas en Europa y América Latina, 1st ed.; Universidad de La Plata: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Inneraty, D. La gobernanza de los territorios inteligentes. EKONOMIAZ 2010, 74, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, P. Cibercultura: La Cultura de la Sociedad Digital; Anthropos: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miedes, B. Territorial Intelligence: Towards a new alliance between sciences and society in favour of sustainable development. Ricerca E Sviluppo Per Le Politiche Soc. 2009, 1, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ivars Baida, J.A.; Solsona Monzonís, F.J.; Giner Sánchez, D. Gestión turística y tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC): El nuevo enfoque de los destinos inteligentes. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 2016, 62, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, M.C.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. ¿Existe gobernanza en la actual gestión de los destinos turísticos? Estudio de casos. Revista PASOS 2014, 12, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Statut Jeune Entreprise Innovante, J.E.I. Available online: https://subventions.fr/dossier-subventions/jeune-entreprise-innovante-jei (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- McKernan, J. Curriculum Action Research: A Handbook of Methods and Resources for the Reflective Practitioner, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, C.A. Investigación Cualitativa, 1st ed.; ICFES: Bogotá, Colombia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Investigación con Estudio de Casos, 1st ed.; Morata: Madrid, España, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilachis, I. Estrategias de Investigación Cualitativa, 1st ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, España, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Investigación Sobre Estudio de Casos. Diseño y Métodos. Applied Social Research Methods Serie, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2003; Volume 5, Available online: https://bit.ly/36qPJVs (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Wanner, P. Les Oiseaux de Passage, Plate-Forme Communautaire, Sociale et Solidaire. Espaces 2019, 348, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, P. For a living European Heritage that creates debate and is a shared responsibility. Cartaditalia 2018, 2, 445–453. [Google Scholar]

- Les Oiseaux de Passege. Available online: https://www.lesoiseauxdepassage.coop/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Research Tax Credit. Available online: https://www.impots.gouv.fr/portail/international-professionnel/tax-incentives#TTC (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Convention Industrielle de Formation par la Recherche of the Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur, de la recherche et de l’innovation (France) CIFRE. Available online: https://www.enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr/cid67039/cifre-la-convention-industrielle-de-formation-par-la-recherche.html (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Faro Convention Action-Research Network of the Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-research (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Song, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, G. Tourism value chain governace: Review and Prospects. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merinero Rodríguez, R.; Pulido Fernández, J.I. Desarrollo turístico y dinámica relacional. Metodología de análisis para la gestión activa de destinos turísticos. Cuadernos De Turismo 2009, 23, 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, L.; Marshall, C.; Bassett, M. Partnerships: Putting Good Governance Principles in Practice; Institute on Governance: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006; Available online: https://bit.ly/2XChK8H (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Pulido, M.C.; y Pulido, J.I. Destinos turísticos. Conformación y modelos de gobernanza. In Estructura Económica de los Mercados Turísticos, 1st ed.; Pulido, J.I., Cárdenas, P.J., Eds.; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanquar, R.; Rivera, M. “El proyecto “TRES” y la “Declaración de Córdoba” (España). Una apuesta por la articulación de estrategias de turismo responsable y solidario desde Europa”. PASOS 2010, 8, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón-Campos, J.L. Economía Social y conceptos afines: Fronteras borrosas y ambigüedades conceptuales del Tercer Sector, CIRIEC—España. Revista de Economía Pública Social y Cooperativa 2006, 56, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Magnaghi, A. La Biorégion Urbaine. Petit Traité Sur le Territorie Bien Commun; Eterotopia: Rhizome, France, 2014. Available online: http://www.eterotopiafrance.com/tag/architecture/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Rabbiosi, C.; Giovanardi, M. Beyond the Great Beauty: Rescaling Heritage and Tourism. Almatourism J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2017, 8, 1–309. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design When Everybody Designs, 1st ed.; The MIT Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy, 2nd ed.; Hachette: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.L.; Riddell, D.; Vocisano, D. Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: Strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2015, 58, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cooperative Principles | Realization on the Les Oiseaux de Passage Platform |

|---|---|

| Primacy of the social objective over capital | The technology is at the service of people (guests and hosts). |

| Transparency and equity | Transparent, fair and economical fees: each professional selects the pricing scheme most appropriate to their circumstances, and benefits directly from the different services included. Payment is by annual fee irrespective of volume of sales. (By contrast, the major platforms charge up to 20% of sales.) |

| Voluntary and open membership | Hosts, grouped into communities, can request voluntary and open membership of the cooperative. Other members of the cooperative are distributors of the offer (travel agents, workers’ committees, and tourist associations), universities and researchers. |

| Democratic control by the membership | The communities are a statutory majority, represented directly or through their networks, and participate democratically in its governance. |

| The combination of individual and general interests | Each community and each of its members has their own website where they can freely promote themselves and share contacts with other communities and destinations. This constitutes a collective response to the diversity and evolution in travel patterns and web use. |

| Cooperation | The platform provides a tool for collaboration and, particularly, cooperation between hosts in different communities and destinations. |

| Autonomous management and independence from public authorities | The cooperative has its own structure, objectives and management criteria, independent of the public administration, and managed by its members. |

| Collective interest of the cooperative | This kind of platform cooperativism aims to reappropriate, on behalf of the workers and users, the latest developments in ICT applied to the hospitality and travel sector, in the form of, in this instance, collaborative online platforms. |

| Territorial focus with global reach | Although each offer is rooted in a specific territory, community and host, the content (offers, stories, content) can be freely exported to other digital media (digital badges, interoperability). |

| Reinvestment of the essential surplus for general interest | Profits are put into the creation of indivisible reserves and a research and development fund. |

| Strategic vision | The platform aims to meet a plural, inclusive demand for travel and accommodation experiences, in particular the trend towards coproduction with the traveller (preferred by 50% of users), and emerging purposes for travel: more fulfilling contact with locals, escape from standardisation, and so on. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miedes-Ugarte, B.; Flores-Ruiz, D.; Wanner, P. Managing Tourist Destinations According to the Principles of the Social Economy: The Case of the Les Oiseaux de Passage Cooperative Platform. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124837

Miedes-Ugarte B, Flores-Ruiz D, Wanner P. Managing Tourist Destinations According to the Principles of the Social Economy: The Case of the Les Oiseaux de Passage Cooperative Platform. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124837

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiedes-Ugarte, Blanca, David Flores-Ruiz, and Prosper Wanner. 2020. "Managing Tourist Destinations According to the Principles of the Social Economy: The Case of the Les Oiseaux de Passage Cooperative Platform" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124837

APA StyleMiedes-Ugarte, B., Flores-Ruiz, D., & Wanner, P. (2020). Managing Tourist Destinations According to the Principles of the Social Economy: The Case of the Les Oiseaux de Passage Cooperative Platform. Sustainability, 12(12), 4837. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124837