A Quantitative Analysis of the Optimal Energy Policy from the Perspective of China’s Supply-Side Reform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

3. Model

3.1. Final Goods

3.2. Intermediate Goods

3.3. Energy Producer

3.4. Energy Producer

3.5. Market Clearing

- Intermediate goods market.

- Energy market. In equilibrium, the energy demand for the two types of intermediate products should be equal to the energy output.

- Labor market. The supply of workers L is normalized to 1, which equals the number of workers employed by high and low energy-consuming firms.The supply of scientists S is exogenously calibrated to match the ratio of scientists to workers. (The number of scientists refers to actual staff with college degrees or higher working in the energy sector).

4. Numerical Results

4.1. Calibration and Model Validation

4.2. Quantitative Results

4.3. Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

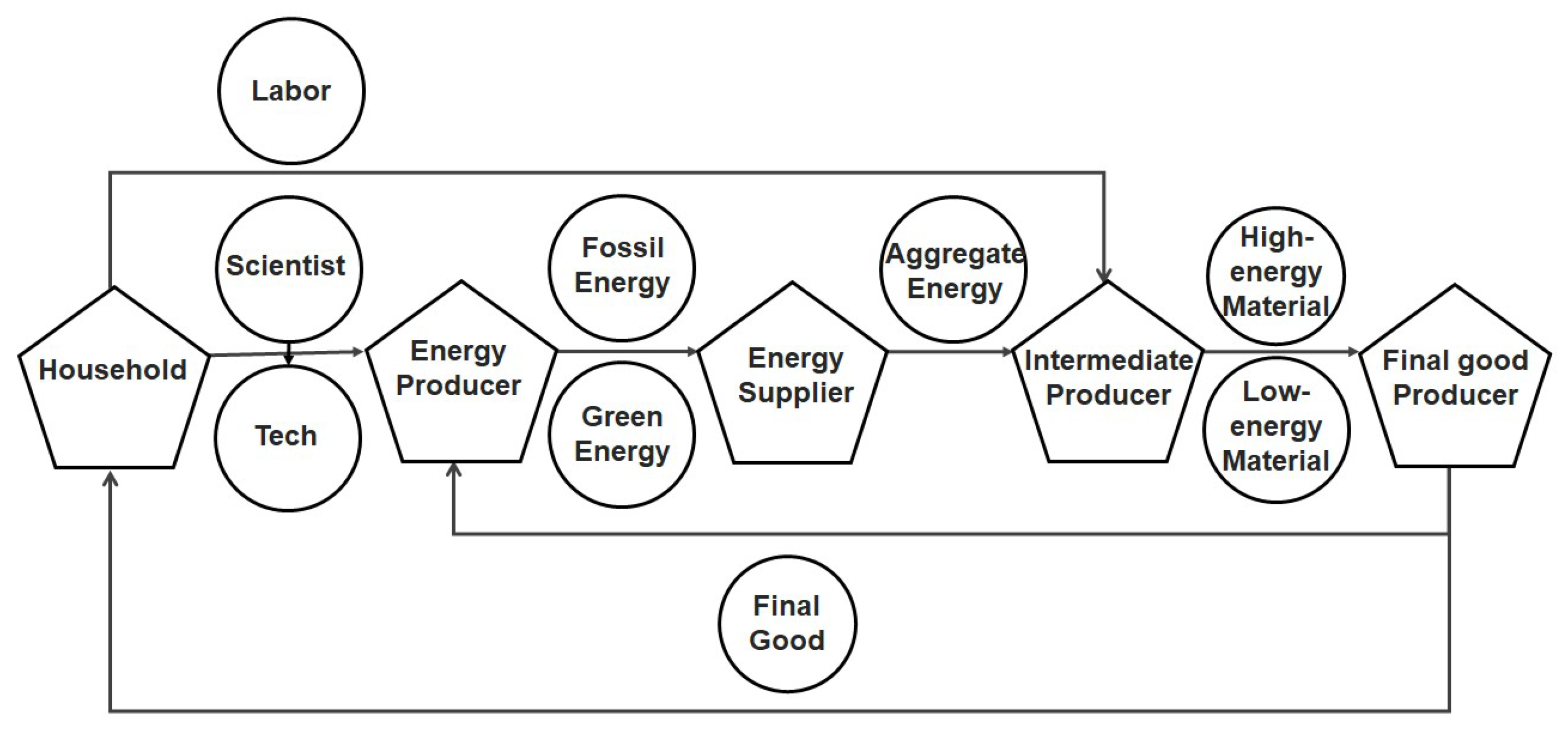

Appendix A. A Descriptive Diagram

Appendix B. Computation

Appendix C. Results

| BGP | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross output:Y | 0.348 | 0.305 | 0.300 | 0.306 |

| (−12.31%) | (−13.83%) | (−12.18%) | ||

| Fossil energy:F | 0.391 | 0.417 | 0.420 | 0.403 |

| (6.72%) | (7.56%) | (3.28%) | ||

| Green energy:G | 0.424 | 0.534 | 0.513 | 0.557 |

| (66.36%) | (53.67%) | (76.09%) | ||

| Energy structure:G/(F+G) | 0.288 | 0.478 | 0.442 | 0.506 |

| (26.02%) | (20.90%) | (31.26%) | ||

| Energy:E | 0.495 | 0.472 | 0.431 | 0.462 |

| (−4.75%) | (−13.00%) | (−6.78%) | ||

| Scientists in industry F: | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| (−28.23%) | (−28.71%) | (−18.89%) | ||

| Scientists in industry G: | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| (28.73%) | (39.41%) | (18.07%) | ||

| Technology of industry F: | 2.212 | 2.378 | 2.377 | 2.394 |

| (7.48%) | (7.44%) | (8.21%) | ||

| Technology of industry G: | 1.818 | 2.054 | 2.065 | 2.038 |

| (13.03%) | (13.63%) | (12.11%) | ||

| Technology of industry G:A | 2.038 | 2.237 | 2.241 | 2.239 |

| (9.76%) | (9.97%) | (9.85%) | ||

| Price of industry M: | 0.522 | 0.578 | 0.572 | 0.577 |

| (10.79%) | (9.54%) | (10.50%) | ||

| Price of industry F: | 0.360 | 0.394 | 0.488 | 0.401 |

| (9.45%) | (35.50%) | (11.33%) | ||

| Price of industry G: | 0.423 | 0.371 | 0.472 | 0.356 |

| (−12.12%) | (11.73%) | (−15.80%) | ||

| Relative energy price:/ | 1.173 | 0.0.941 | 0.967 | 0.887 |

| (−19.71%) | (−17.55%) | (−24.37%) |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Nie, R. Enterprise investment, local government intervention and coal overcapacity: The case of China. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulter, J. China’s Supply-side Structural Reform. Reserve Bank-Aust. Bull. 2018, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gutowski, T.G.; Sahni, S.; Allwood, J.M.; Ashby, M.F.; Worrell, E. The energy required to produce materials: Constraints on energy-intensity improvements, parameters of demand. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 2013, 371, 001–003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.Y.; Wu, H.-M.; Xing, Y. “Wave Phenomena” and Formation of Excess Capacity. Econ. Res. J. 2010, 10, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, G.; Guo, Y. Why is there overcapacity in China’s PV industry in its early growth stage? Renew. Energy 2014, 72, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, S.; Sha, Y.; Ding, Q.; Yuan, J.; Guo, X. Coal power overcapacity in China: Province-Level estimates and policy implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Liu, Y. Coal overcapacity in China: Multiscale analysis and prediction. Energy Econ. 2018, 70, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shen, X.; Zhang, K.; Dong, L. Coal power overcapacity and investment bubble in China during 2015–2020. Energy Policy 2016, 97, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Hou, X.; Han, J.; Zhang, L. The drivers of coal overcapacity in China: An empirical study based on the quantitative decomposition. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wan, K.; Song, X.; Liu, Y. Provincial allocation of coal de-capacity targets in China in terms of cost, efficiency, and fairness. Energy Econ. 2019, 141, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lua, C.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y. The impacts of policy mix for resolving overcapacity in heavy chemical industry and operating national carbon emission trading market in China. Appl. Energy 2019, 204, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. Directed technical change. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2002, 4, 781–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulders, S.; De Nooij, M. The impact of energy conservation on technology and economic growth. Resour. Energy Econ. 2003, 1, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Akcigit, U.; Hanley, D.; Kerr, W. Transition to clean technology. J. Political Econ. 2016, 1, 53–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. Directed technological change: It’s all about knowledge. Swed. Univ. Agric. Sci. Dep. Econ. Work. Pap. Ser. 2012, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, L.H.; Stephen, H.S. Induced technological change and the attractiveness of CO2 abatement policies. Resour. Energy Econ. 1999, 21, 211–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D. ENTICE: Endogenous technological change in the DICE model of global warming. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2004, 48, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlagh, R. A climate-change policy induced shift from innovation in carbon-energy production to carbon-energy savings. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Aghion, P.; Bursztyn, L.; Hémous, D. The Environment and Directed Technical Change. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 1, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, S. Climate policy and innovation: A quantitative macroeconomic analysis. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2018, 1, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heutel, G. How should environmental policy respond to business cycles? Optimal policy under persistent productivity shocks. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2012, 2, 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Springborn, M.R. Emissions targets and the real business cycle: Intensity targets versus caps or taxes. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 3, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, K.; Economides, G.; Philippopoulos, A. What is the Best Environmental Policy? Taxes, Permits and Rules under Economic and Environmental Uncertainty. Athens Univ. Econ. Bus. DEOS Work. Pap. 2010, 3, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dissou, Y.; Karnizova, L. Emissions cap or emissions tax? A multi-sector business cycle analysis. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 79, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method of Moments | Data | Model |

|---|---|---|

| Ratio of energy consumption of industry M: /E | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| Ratio of energy supply of industry F: F/E | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| Ratio of scientists in industry G: /S | 0.41 | 0.43 |

| Scientist structure of the energy production sector: / | 1.44 | 1.33 |

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Final goods production | ||

| Output elasticity of substitution: | 0.95 | — |

| Distribution of high energy-consumption materials: | 0.6 | Data |

| Intermediates production | ||

| Labor share of high energy-consumption materials: | 0.19 | Data |

| Labor share of low energy-consumption materials: | 0.49 | Data |

| Number of workers: L | 1 | Normalization |

| Production shock of sector M in policy 1: | 0.90 | Method of moments |

| Production shock of sector F in policy 2: | 0.88 | Method of moments |

| Production shock of sector M in policy 3: | 0.91 | Method of moments |

| Production shock of sector F in policy 3: | 0.93 | Method of moments |

| Energy production | ||

| Capital share of fossil energy: | 0.915 | Method of moments |

| Capital share of green energy: | 0.599 | Method of moments |

| Energy supply | ||

| Energy elasticity of substitution: | 1.5 | Literature |

| Distribution of fossil energy: | 0.5 | — |

| Research | ||

| Cross-sector spillovers: | 0.5 | Literature |

| Diminishing returns: | 0.79 | Literature |

| Scientist efficiency: | 6.017 | Method of moments |

| Sector size of fossil producers: | 1 | Normalization |

| Sector size of green producers: | 0.773 | Data |

| Number of scientists: S | 0.01 | Data |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xi, J.; Wu, H.; Li, B.; Liu, J. A Quantitative Analysis of the Optimal Energy Policy from the Perspective of China’s Supply-Side Reform. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124800

Xi J, Wu H, Li B, Liu J. A Quantitative Analysis of the Optimal Energy Policy from the Perspective of China’s Supply-Side Reform. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124800

Chicago/Turabian StyleXi, Jianming, Hanran Wu, Bo Li, and Jingyu Liu. 2020. "A Quantitative Analysis of the Optimal Energy Policy from the Perspective of China’s Supply-Side Reform" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124800

APA StyleXi, J., Wu, H., Li, B., & Liu, J. (2020). A Quantitative Analysis of the Optimal Energy Policy from the Perspective of China’s Supply-Side Reform. Sustainability, 12(12), 4800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124800