1. Introduction

The concept of collective impact has drawn attention from various disciplines seeking to understand social innovation [

1]. The seminal work of Kania and Kramer [

2] provides a clear definition and rich illustrations of the idea, and many scholars and practitioners have sought to promote it [

3,

4,

5,

6]. There has been a great deal of supporting evidence of collective impact in various contexts, but critiques of the thesis have also been made [

7]. Stachowiak and Gase [

7] emphasize that implementing a collective impact is not as straightforward as formulating it. In other words, the thesis of collective impact assumes that proper partners exist who can share the goals of the collaborative work and give their full commitment to it, but it does not closely examine how engaging actors can have a collective impact that persists [

7]. Collective impact has largely been understood as a static outcome or a goal, but as Stachowiak and Gase [

7] suggest, it can perhaps best be understood as a process and, they note, the conditions for collective impacts are inter-related. This suggests that we need to expand our knowledge on collective impact by acknowledging that collective impact is indeed socially constructed through ongoing interactions among various actors. This social construction aspect of collective impact could be empirically investigated. That is, we can be asked: how can collective impact, once formed, be developed and evolved over time? By elaborating our understanding of collective impact to view it as a process, we tackle the questions of its implementation [

8].

In this study, adopting the given conceptualization of collective impact, we develop a new perspective to assess robustness in collective impacts. A robust collective impact is one that is not strongly influenced by other internal, external, or relational factors, leading to long-lasting results. The nature of a social economy, in which actors pursue social impact through achieving economic values, leads its actors to discern the difference between economic and social values, and they accordingly show divergent social praxis between organizations [

9,

10]. Even though organizations seek shared goals and may work together, the resulting collective impact may be localized depending on which value is prioritized. Thus, if collective impact is sought by corporations, which are conventionally considered to be motivated by the pursuit of economic value, the achievement of collective impact in the face of this can be a challenge. This challenge can restrict collective action from being mobilized across boundaries, as corporations should form coalitions with actors who are oriented to social values, such as nonprofits, the local community, or other actors in civil society. Furthermore, even if cross-boundary partnerships are formed, they may not persist because they have different and often contradictory views on how to achieve social impact, and conflict may result [

11].

In this study, we investigate how collective impact can be achieved and sustained under the leadership of corporations. H-OnDream is a corporation-driven program that has appeared in South Korea and supports nascent social enterprises as they develop their business ideas, financially and otherwise. Since its inception in 2011, H-OnDream has supported more than 220 social enterprises and created more than 1600 jobs through them. Additionally, the social enterprises, on average, could increase their revenues by more than 330% because of H-OnDream. As a result, H-OnDream gained a reputation as a model intervention. Because corporations may not deeply engage in social innovation or other work for social impact, the case of H-OnDream can exhibit potential obstacles to collective impact that can appear where a corporation takes the initiative and establishes a backbone, illustrating how collective impact can be more effectively implemented.

This paper consists of five parts.

Section 2 presents theoretical background regarding collective impact. In particular, corporation-driven collective impact and robust collective impact are specified. In

Section 3, the methods used for our study are explained in detail. In

Section 4, our findings from the H-OnDream case are presented. Then, in the last part, we elaborate how we can understand the findings, and we provide theoretical and practical implications on robust collective impact as well as suggestions for future studies.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Corporation-Driven Collective Impact

Based on the concept of collective impact, the collective impact framework has been comprehensively understood as cross-sector and interdisciplinary collaborative work aimed at developing common understanding and addressing multifaceted social problems involving various stakeholders like government, businesses, civil groups and community leaders [

1,

2]. Collective impact requires five conditions: a common agenda, shared measurements, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and backbone support [

8]. Here, the role of the backbone organization is vital [

8]. The managerial challenges that exist to the achievement of collective impact must be reconciled through a backbone organization [

12,

13].

Most backbone organizations are in the public sector or are nonprofits, as these types of organization have long experience with social issues, legitimizing their initiative are throughout society [

1,

14]. The roles that for-profit corporations play in collective impact, therefore, are partial or simple, i.e., mostly concentrated on funding [

15]. That means that corporations usually do not take the initiative to produce collective impact. While, from a conceptual point of view, collective impact can feature corporations in the lead among backbone organizations, from a practical point of view, corporations might not seek the role of a backbone organization because they are pursuing their own goals, which may not perfectly match to the concept of collective impact.

However, this does not mean that corporation cannot take initiative in this area. For corporations, collective impact can be a source for their CSR activities [

16,

17]. Prompted by the social expectations that their stakeholders may have, corporations often do actively engage in social issues [

18,

19]. In response, corporations allocate resources to charitable actions or give philanthropic contributions, explicitly or implicitly [

16]. However, this direct action is not considered legitimate or authentic within corporations, because it is not a core activity for the corporation’s value chain and is also considered to be a social cost that could come into conflict with shareholder wealth [

20]. Thus, cross-sector partnerships may be a positive alternative for CSR actions [

17]. However, such partnerships are not a cure-all. Because different actors seek different interests, the participation of an organization tends to secure its own self-interest [

21]. This implies that social partnerships are a matter of persistence, not formation [

12]. For inter-organizational relationships to persist, relevant uncertainty, such as resource dependence [

22,

23,

24], agency issues [

25,

26], or transaction costs [

27,

28], should be effectively countered. As a result of this collective impact driven by corporations can produce unexpected outcomes relative to nonprofits unless these contingencies are reconciled [

29,

30].

2.2. Robust Collective Impact

Robust collective impact refers to the collective impact that persists, coping with the uncertainty that arises from cross-boundary partnerships. In robust collective impact, backbone organizations, taking on the leadership for the impact, effectively mobilize resources from diverse participants, reconciling any conflict among them and reducing social costs rooted in the relationships entailed. This role that backbone organizations can play is rooted in multivocality, or “the fact that single actions can be interpreted coherently from multiple perspectives simultaneously, the fact that single actions can be moves in many games at once, and the fact that public and private motivations cannot be parsed” [

31] (p. 1263). This allows backbone organizations to “maintain engagement across conflicting positions” [

32] (p. 372). The presence of diverse participants who have various interests and agendas requires a more explicit focus on the role of backbone organizations in coping with uncertainty and complexity in their social structures.

Padgett and Ansell [

33] coined the term of robust action to assess this type of multivocality; specifically, it refers to “noncommittal actions that keep future lines of action open in strategic contexts where opponents are trying to narrow them” [

33] (p. 24). When participants’ contributions to collective impact cannot be easily predicted, or potential conflict among participants can be predicted, the presence of a backbone organization tends to preserve flexibility [

34]. That is, robust action requires that “discretionary options across unforeseeable futures in the face of hostile attempts by others to narrow those options” [

31] (p. 1263) be maintained. In response to these factors, robust collective impact seeks to balance flexibility and robustness to achieve multivocality.

Related to this, Banyai and Fleming [

3] focused on collective impact capacity building by illuminating that how collaborative networks can be developed and leadership of the backbone organizations can be strengthened. Given that collective impact comes up with participation of diverse partners, stakeholders, and community members, backbone organizations are required to build up their capacity to integrate diverse perspectives and interests from diverse participants. This implies that ways to build up collective impact capacity can make collective impact last long, which is understood as robust collective impact.

3. Methodology

To specify the ways in which backbone organizations can achieve a robust collective impact, we employ a qualitative approach, focusing empirically on the case of H-OnDream, the initiative of a corporation that generated a robust collective impact. H-OnDream was a one-year CSR program of the Hyundai Motor Company (HMC), developed through cross-boundary partnerships, to purse the goal of nurturing social enterprises. Seeking young people who have interesting ideas and are strong minded, H-OnDream partnered with a range of ecosystem incumbents (such as nonprofits, funders, investors, incubators, accelerators, and other organizations engaged in social innovation) to create an environment where social enterprises could be supported both financially and in other ways to actualize their social mission.

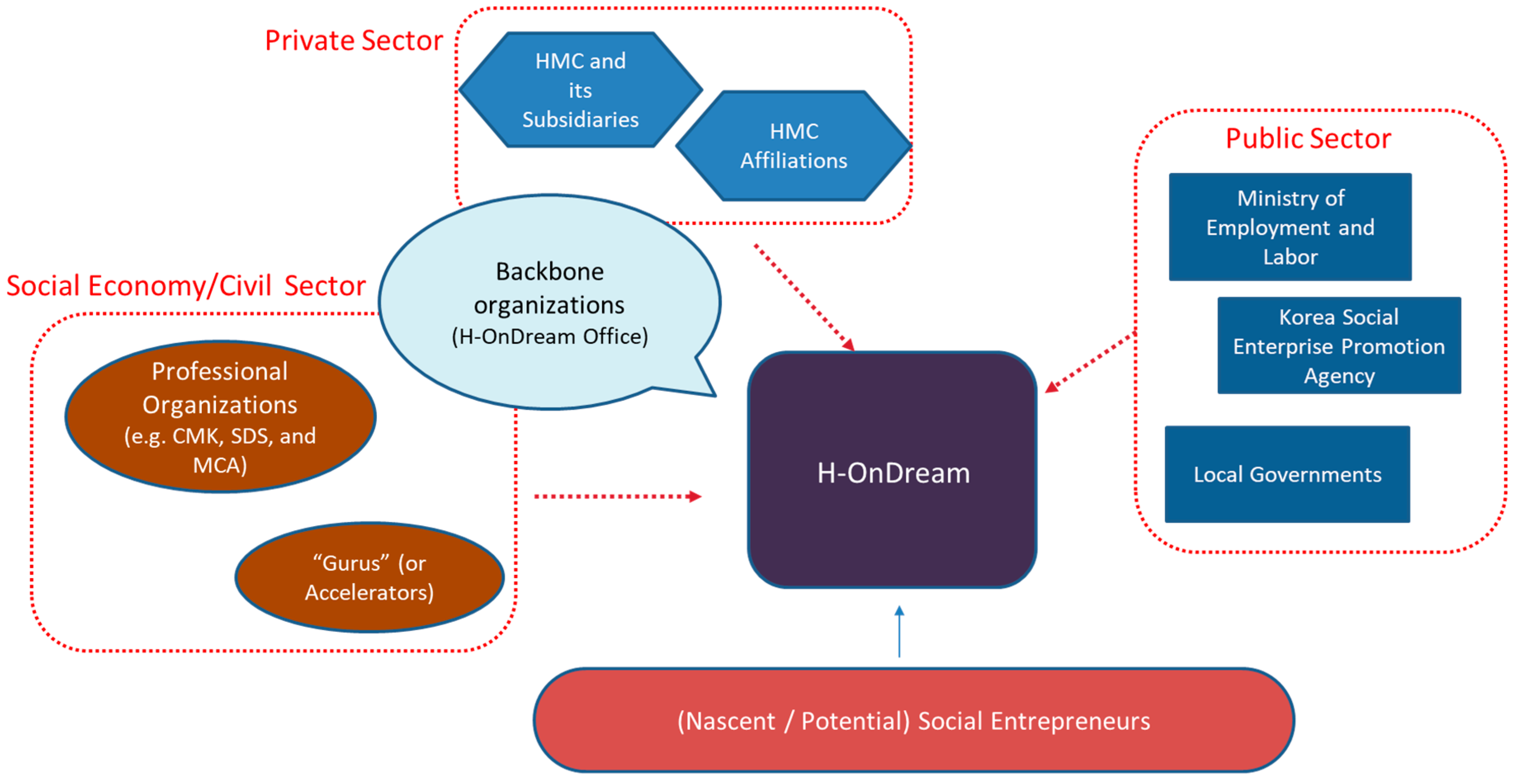

Figure 1 shows which ecosystem incumbents are involved in the creation of H-OnDream. Specifically, for H-OnDream, there were three sectors of engagement. In the public sector, hoping to address the social issues regarding employment, the Korea government initially participated in designing H-OnDream. In particular, the Ministry of Employment, the Labor and Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency, and local governments constituted a political environment where social enterprises were supported and nurtured. In the private sector, HMC, HMC subsidiaries, and their affiliated businesses (e.g., suppliers) were directly and indirectly associated with H-OnDream. These for-profit organizations played roles for establishing business environments for social enterprises. In the civil sector, professional organizations pursuing social economy, such as nonprofits, activists, and impact investors, were engaged in the operation of H-OnDream by guiding and assisting social enterprises. Additionally, business gurus were partnered to join the H-OnDream program. Last, nascent or potential social entrepreneurs were the member of ecosystem as the target entities H-OnDream attempted to support.

We collected data from multiple sources because collective impact, by definition, requires collaboration from multiple partners, so if data were collected from a single source, a measurement bias could result. The primary data were drawn from documents supplied by the backbone organization, the H-OnDream Office, but we also collected participant observation data by involving in the H-OnDream program, such as mentoring and attending board meetings and presentations in international fora between 2018 and 2020. The information obtained in this way also served as a tool to specify the collective impact.

We conducted in-depth interviews using the data thus collected as a guide. The interviews for this study were conducted in a three-stage process. First, we interviewed the main decision makers for H-OnDream, who include a vice president and a director of the department of Society and Culture at HMC. These two figures took the initiatives for H-OnDream from the beginning. As they planned, designed, and organized the whole parts of the program, we asked them why they had decided to take the initiatives for H-OnDream and how the H-Ondream could have been created. To clarify their answers, we conducted both formal and informal interviews for both interviewees. We requested each for a formal interview at first and then we had informal conversations through emails and phone-calls. During these informal conversations, we asked them the questions raised while we described the initial stage of H-OnDream. In particular, the informal conversations were intensively made when we attended international fora with them. Then, certain collaborators for H-OnDream, including incubating organizations, accelerators, and private investors, were interviewed. There were two incubating organizations involved in H-OnDream. We interviewed one director of an incubating organization and two former associate directors from the organization. Of the two associate directors, one was actively involved in designing the H-OnDream program and the other took charge in implementing it. Then, we interviewed two accelerators and a private investor. They joined the H-OnDream program in 2017, which was the year that accelerating activities, as a sub-program, were organized under the H-OnDream program. In these groups, we sought to know how and why each of them decided to collaborate with the H-OnDream Office and what activities each of them carried out during the program.

The entire interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed and compared with the official documents on H-OnDream. Because these three groups played the role of service providers, we needed to validate whether the beneficiaries had same perception on H-OnDream. In the last stage of our interview, we randomly sampled social entrepreneurs who had obtained the support of H-OnDream to investigate what they were able to accomplish with H-OnDream and how helpful the organization was. To sample social enterprises, we used the whole list of the 224 social enterprises which had joined the H-OnDream program. With the list, we requested randomly chosen social enterprises for a formal interview and interviewed once they accepted it. In total, seven social enterprises were interviewed (See

Appendix A Table A1). We asked what brought them to H-OnDream and how it worked. These interviews were also audio-recorded and transcribed.

Using these data sources, we established how the collective impact of H-OnDream is constructed over time. For this, we used a process-based approach. That is, in this study, we do not attempt to explicate how collective impacts can be identified with H-OnDream. Instead, we focused on how the H-OnDream program constructed its collective impact over time. Thus, five conditions for collective impact were initially considered to demonstrate how collective impacts could be developed, but we focused on how the five conditions had been achieved. Our analysis traced how the cohorts of the backbone organizations interacted with each other to pursue common goals.

4. Case of H-OnDream

4.1. Overview of H-OnDream

H-OnDream was established to help support the ecosystem of social enterprises as part of an effort to address unemployment in Korea. Previously, focusing on the unemployment among senior citizens, HMC had enabled social enterprises to develop and implement CSR programs to help senior citizens commute. However, while this did help alleviate unemployment, the activities required a large investment of resources, reducing funds available to pursue other social goals. Hoping to increase the spectrum of social impacts, HMC partnered with SDS, a nonprofit organization that pursues social innovation. This partnership was necessary for two reasons. First, HMC realized that it had limited experiences in effective social impact. Further, HMC could not marshal more than limited resources, a CSR could not be a core activity under the logic of HMC’s main value chain. Thereupon, HMC removed itself from the implementation of its own CSR programs. Second, SDS, which is renowned its design and implementation of programs supporting social movements by mobilizing resources from a range of sources, had proposed a project to support and nurture nascent social entrepreneurs. HMC hoped that this project could expand their potential social impact to new fields and accepted the proposal. This is how H-OnDream came out.

Upon implementing H-OnDream, a concern expressed by HMC was how financial resources could be attained. Because the program for supporting and nurturing nascent social entrepreneurs was not directly aligned to the main business of HMC, there was no strong consensus in favor of launching the program. HMC turned its attention to external institutions to locate resources, contacting for instance CMF, a private foundation for culture and the arts, which had developed a close relationship with HMC, to propose a partnership in the program. The foundation accepted the offer, participating as a funder. Then, MCA, a professional organization in culture and the arts, was invited as a backbone organization in H-OnDream. SDS played a main role in implementing H-OnDream, its expertise did not extend to social enterprises working in culture and the arts, so MCA took the role of supplementing in this area.

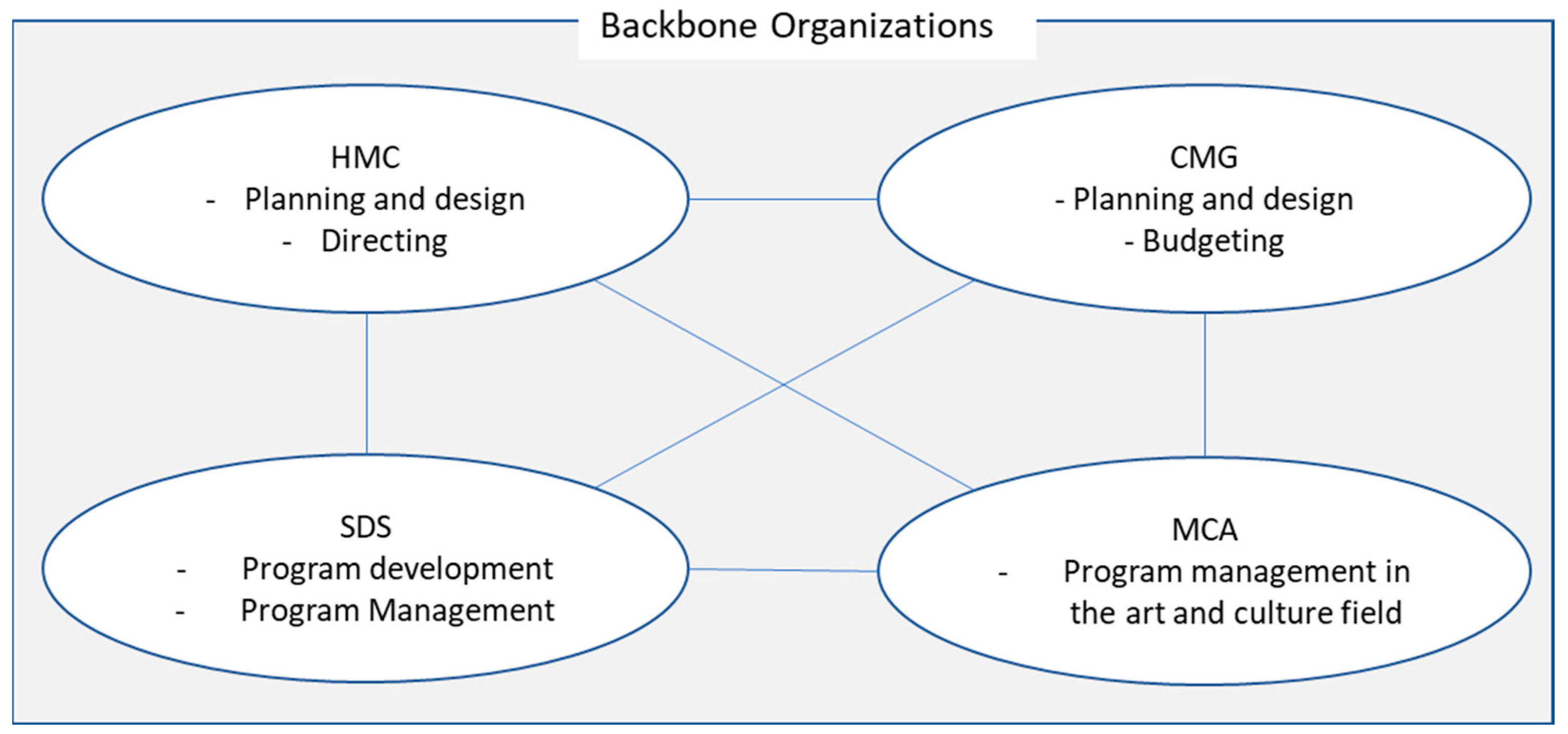

Figure 2 presents the backbone structure for H-OnDream.

Because H-OnDream is a product of cross-boundary collaboration, its outcomes constitute a collective impact. More precisely, the five conditions for collective impact are met by H-OnDream. H-OnDream is an illuminating illustration of collective impact. First, multiple players have the common goal of addressing the unemployment by supporting social enterprises. This matches the first condition of collective impact, having a common agenda. From this goal, a clear rubric could be developed to evaluate the outcomes of H-OnDream, i.e., the unemployment rate. Each year, SDS publishes the survival rates of the social enterprises that participate in H-OnDream, and HMC publishes how the participants are helping meet the Sustainable Development Goals [

35]. This can be understood as an achievement of H-OnDream, but it also shows how the outcomes of H-OnDream can be shared throughout society. The second condition, shared measurement, is fulfilled in this way. Third, the backbone organizations all have roles to play in producing the collective impact. HMC takes charge of all of the planning and organizing, SDS and MCA do the practical implementation of HMC’s designs, and CMF provides the financial resources. Fourth, continuous communication is considered essential by these organizations and the participating social enterprises. Last, support is produced by multiple cohorts of backbone organizations. The four organizations support the dedicated organization H-OnDream Office; they cohesively interact with each other to ensure proper implementation of the program.

4.2. Potential Perils of Collective Impact

As diverse parties jointly seek to produce a social impact while taking their own interests into account within the structure of H-OnDream, unseen strains have developed within the backbone organizations. The main issue here is how to localize the goals of the cohorts. That is, each organization that participates in the collective impact has its own understanding of how to create collective impact. Based on these, the backbone organizations’ behavioral consequences are distinct. For H-OnDream, there were, broadly speaking, two sets of expectations for its social impact. The first set was market-oriented: H-OnDream was expected to play an ecosystem role in commercial entrepreneurship.

“We thought that the growth process for social enterprises would be the same as that of commercial ventures. Social ventures are also concerned with how they can expand their customer base in the market, and they devise strategies to seek competitive advantages. H-OnDream was intended to help these enterprises succeed through our acceleration program.”

(VP of HMC)

“We considered H-OnDream as a crucial program because it could give social enterprises additional opportunities for growth.”

(Director of CMF)

The other expectation was that it would resolve social issues. This expectation dictates that the outcomes of H-OnDream should be measured in terms of new jobs are created, ideally jobs filled with young people.

“We have warned our collaborators that social ventures should not treat disadvantaged superficially, and thus their business models should focus on actual benefits. Otherwise, we don’t need to include them in H-OnDream.”

(Director of SDS)

“Originally, H-OnDream was designed to tackle the unemployment among young people. In general, as firms grow, they can hire more people. We expected that nascent social enterprises that are nurtured and grown through H-OnDream will hire more people, and as the number of growing social enterprises increases, unemployment would fall.”

(Director of HMC)

These two expectations have the potential for conflict, and resource allocation and joint collaboration could be endangered. In other words, while the organizations worked together, they sought their own goals (e.g., [

21]). Furthermore, such localized goals could prevent H-OnDream from improving its collective impact, pursuing social expectations, and retaining their reputation. When a corporation seeks collective impact, such perils are common because a program can be understood as a means for the corporation’s own performance (e.g., [

16,

36]). This suggests that corporation-driven collective impact will not function as designed unless the backbone organizations have distinct roles and identities for implementing collective impact (e.g., [

36]).

4.3. Strategies for Robust Collective Impact

Despite the potential problems with corporation-driven collective impact, we found that H-OnDream has met with few problems. It is a stable program in the social economy of Korea, and the collaborating organizations have developed closer interactions through investment of more resources to the program. All original organizations are still participating in H-OnDream. This shows that the collective impact generated by H-OnDream is robust. How can a collaboration among sectors lead to a robust collective impact?

We found that what HMC did for H-OnDream is related to robust action [

31,

32]. This robust action implies that social actors strategically utilize their social network consisting of diversified partners [

32]. To deal with the range of interests from different counterparties, HMC sought to understand the cohorts’ interests more deeply, making itself sufficiently flexible to find ways to meet their needs. The strategies gazing, abstracting, and spacing are used to produce a robust collective impact.

4.3.1. Gazing

To allow collective impact to persist over time, additional treatments were sought. Initially H-OnDream was intended to assist nascent social entrepreneurs develop business models. SDS focused on how the social enterprises can bring new jobs to the disadvantaged. While this was helpful for devising new business models that tackle social issues, it could not touch upon firm growth. To support social enterprises as they grew in terms of their firm size and revenues, HMC launched an accelerator program. This indicated that the capability of addressing social issues could be combined with the capabilities for business itself. Because these capabilities are sequentially configured, different perspectives on H-OnDream could be integrated. That is, the unseen goal conflicts drawn from the different expectations of H-OnDream could be mitigated by focusing on either one aspect at a time and then shifting to another.

“We looked back on what we’ve done with H-OnDream. We have quite good numbers on employment rates, survival rates, etc. But I wondered, are we are doing good, not just doing well? We need to focus on social impact. So, we tried to apply the SDGs to what our fellows have done [social enterprises that have participated in H-OnDream]. And we thought that H-OnDream made the participants critically tackle growing social issues, such as the re-development of local areas, local inequality, etc. The Consortium was designed for this reason. We needed to show that H-OnDream really helped with social issues.”

(Director of SDS)

Because the backbone organizations could prioritize different goals, localized goals could be more efficiently pursued [

16,

37].

4.3.2. Abstracting

Abstracting is a strategy that focuses on abstract aspects of goals. This means that other things are put aside and rarely considered. Abstracting indicates a direct connection between an interpretation of an event and a master frame [

38,

39]. Master frames may intensify commitments and forge a shared agenda [

38]. Strang and Meyer [

39] introduced the concept of theorization, in which people connect their cognition of an event to a theorized logic. Thus, abstracting can be understood as the product of a framing processes, which reconstituted the way in which some objects of attention are interpreted as relating to each other [

40].

This means that the relation between the particularistic event and the universalistic structure is utilized as a rhetorical form. Suddaby and Greenwood [

41] observed that theorization, understood as broad statements of appropriate scale and pace of change and the role of agency, can change the institutional logic. Earl [

42] argued that well-framed arguments that adopt abstraction can lead to large-scale changes in values, beliefs, and opinions (p. 519). Polletta [

43,

44] illustrated that the narratives of black students emphasized abstract injustice, which can motivate participation in collective action by aligning individual and collective identities. In relation to this strategy, a director of HMC reflected as follows:

“We just focused on employment issues. We already knew SDS was the expert in this area, so we didn’t care about what they pursued. We gave all the discretion regarding how to manage H-OnDream to SDS.”

(Director of HMC)

Emphasizing social values in collective impact (i.e., H-OnDream) enables parties to bond closely, pay less attention to economic incentives, and pursue common goals.

4.3.3. Spacing

Spacing is another strategy used to promote robust collective impact. HMC highlights the importance of assessment through measurement, but it did not make fine-grained assessments. The other organizations were not entirely dedicated to assessment either, even though they have traced and shared all outcomes for H-OnDream, such as employment rates, growth rates, and survival rates for its participants. This was possible not only due to their close relationships but also to the long-term contracts for H-OnDream. The backbone organizations of H-OnDream had a five-year contract at the initial stage. This led to an avoidance of confrontation with organization-wise interests.

“We know the difference between HMC and SDS and we know that would lead to potential conflict. However, we admitted that the roles SDS plays are crucial for H-OnDream, and we trust the abilities of the directors and staff. We actually learned a lot from SDS. And finally, we found that H-OnDream could make a social impact by empowering SDS. Having different perspectives cannot tell whether SDS’s capacity is worthwhile or not.”

(VP of HMC)

“[SDS] is a nonprofit; we know they have a different perspective on how to generate social impacts… Probably… In fact, we didn’t even notice that SDS had a different point of view on H-OnDream. But the original idea came from SDS, which was what we expected. Even though there are some differences, they might be related to politics. Actually, we have worked together very closely… I trust the director and so does our VP. As we’ve never worked separately, we are never aware of such political things.”

(Director of HMC)

That is, spacing enabled the backbone organizations avoid direct conflict. After the first contract for H-OnDream expired, the backbone organizations continued the relationship, and another five-year contract was signed.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study provides practical insight and academic implications into collective impact. Because shared goals are critical for facilitating cross-boundary collaborations [

45,

46], collective impact should be treated as a process, and it is important to investigate how diverse goals from diverse organizations can be integrated over time. One possible implementation method for collective impact is social partnership [

2], which refers to partnerships formed between public and private sectors to pursue a common goal (especially delivering specific services or benefits for the disadvantages) [

2,

16,

36]. It has been understood that partnerships can effectively mobilize the resources for their common goals. However, social partnership is not easy to achieve, because it requires coping with different perspectives, interests, and goals among the partners [

2,

9,

22].

Acknowledging that collective impact is a process, we contend that such difficulties of social partnership can be overcome through a social construction process. This study investigated the strategies that backbone organizations use in pursuing collective social impact over time. In the case of H-OnDream, we understand that collective impact requires the backbone organizations to cope with uncertainty from the range of participants. The H-OnDream case attests that collective impact is not a one-time thing. It cannot be designed in all particulars at the first stage is constructed over time through ongoing interactions among backbone organizations, their partners, and stakeholders. In this case, the backbone organizations developed their capacity for collective impact over the long run.

In addition, our findings suggest that the three strategies noted above relate to how the relationships among backbone organizations can be further developed. This indicates that it is critical to understand how potential cohorts account for the contexts of social innovation, social impact, and social economy. For collective impact, more than collaboration is required; an integration of differing understandings and expectations regarding social entrepreneurship must be pursued. Cohorts can be selected with respect to their attributes, such as capabilities, expertise, or resources. However, the collective impact they produce cannot come into being unless the backbone structure clearly shows how the cohorts configure social and economic values.

In this study, we demonstrated that a corporation-driven collective impact can persist if the backbone organizations are closely tied to each other and pursue their collective impact in close and ongoing interactions. To achieve this, the robust strategies of gazing, abstracting, and spacing should be pursued. Then, the self-interest of each backbone organization can come to an agreement through these actions, which can help the organizations seek for social value using each organization’s comparative advantages. Thus, self-interest and localized goals can be balanced among these organizations.

While our findings show valuable implications, we acknowledge that this study has some limitations for future studies to address. First, the findings will be examined with multiple cases which represent various contexts. As an in-depth study, this study can shed a light on collective impact, especially robust collective impact. Yet, it requires external validity to be gained. Future studies are thus expected to further our findings with different contexts. Second, longitudinal studies can be more systematically designed to capture how collective impact can persist. In this study, we attempted to follow the historical development of H-OnDream, but it is largely dependent on interviewees’ retrieved facts—a retrospective approach. For future studies, various approaches can be considered to prevent from issues such as potential recall or misclassification biases.