Identifying Corporate Sustainability Issues by Analyzing Shareholder Resolutions: A Machine-Learning Text Analytics Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

Do shareholder resolutions reflect corporate sustainability concerns in terms of environmental, social, and governance aspects?

2. Research Background

2.1. Sustainability

2.2. Shareholder Resolutions

2.3. Text Analytics and Machine Learning

3. Methodology

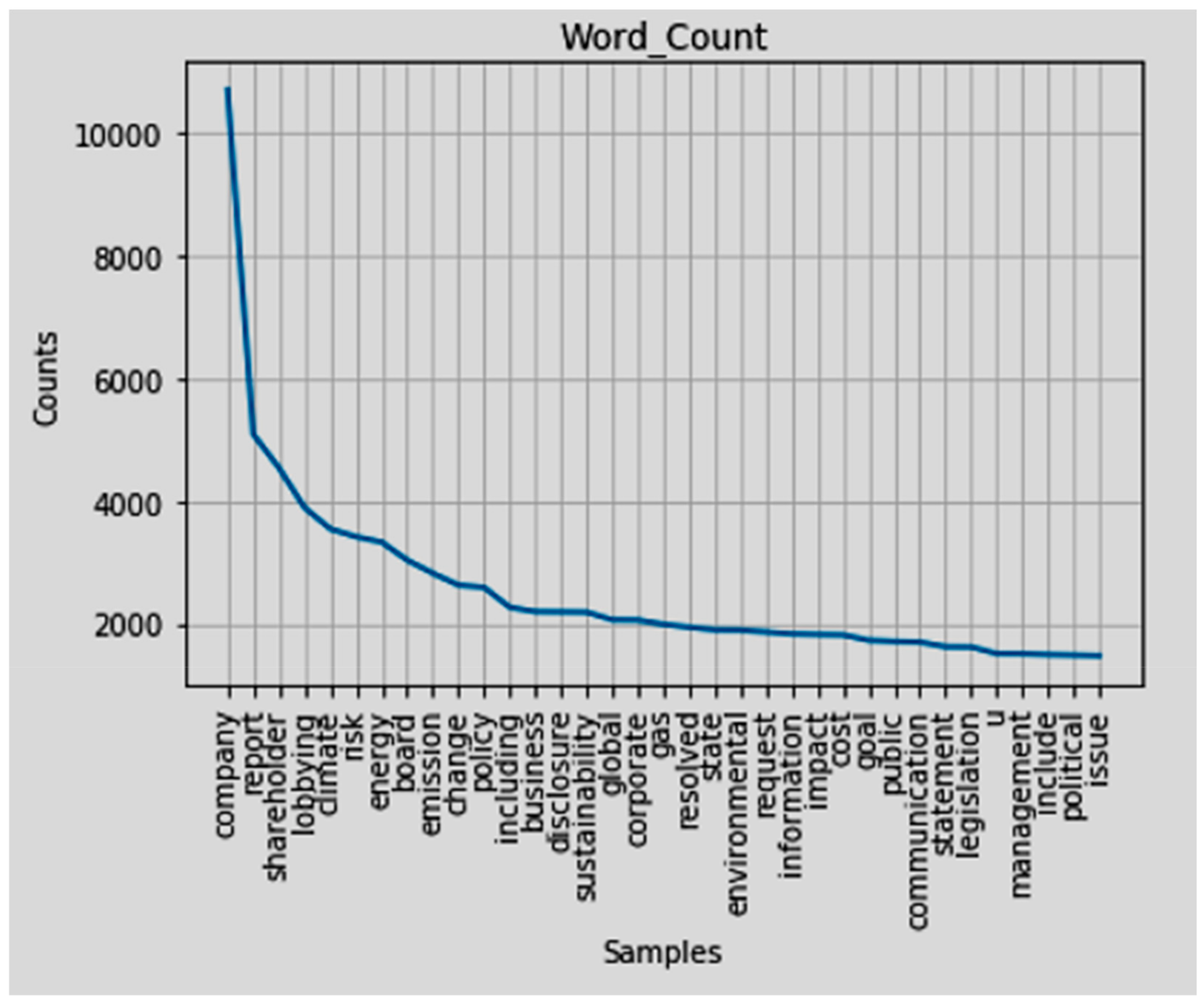

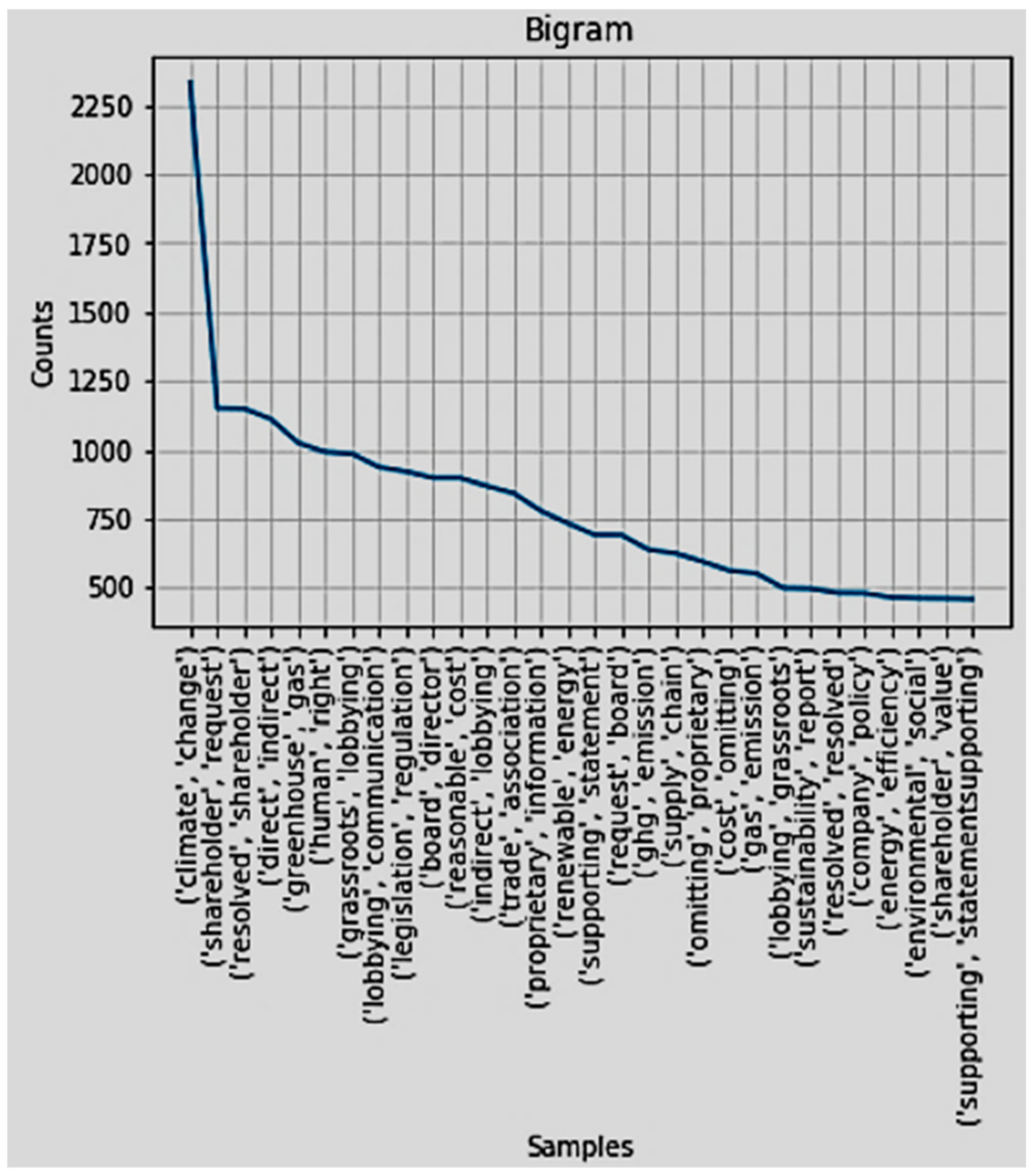

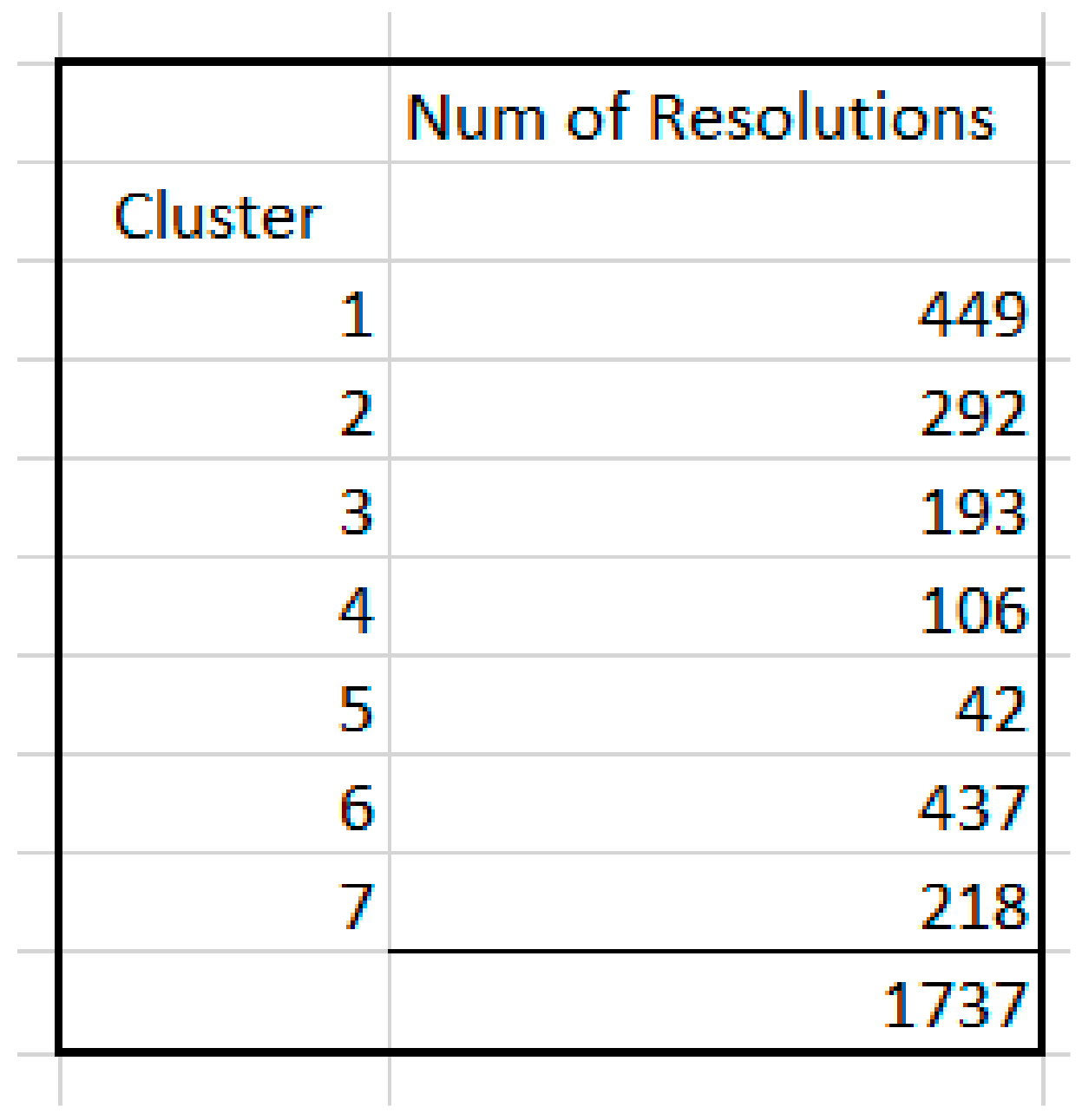

3.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

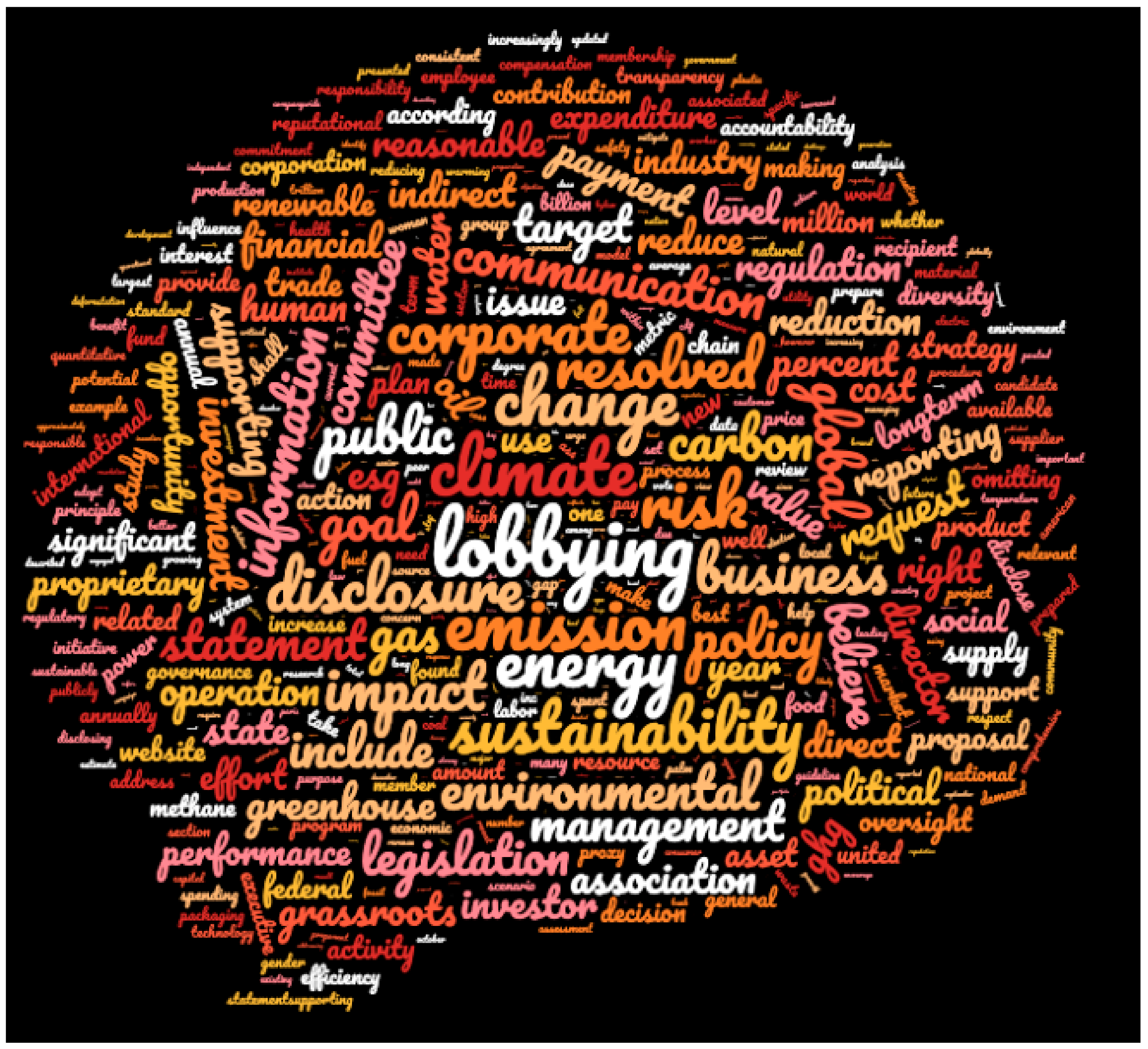

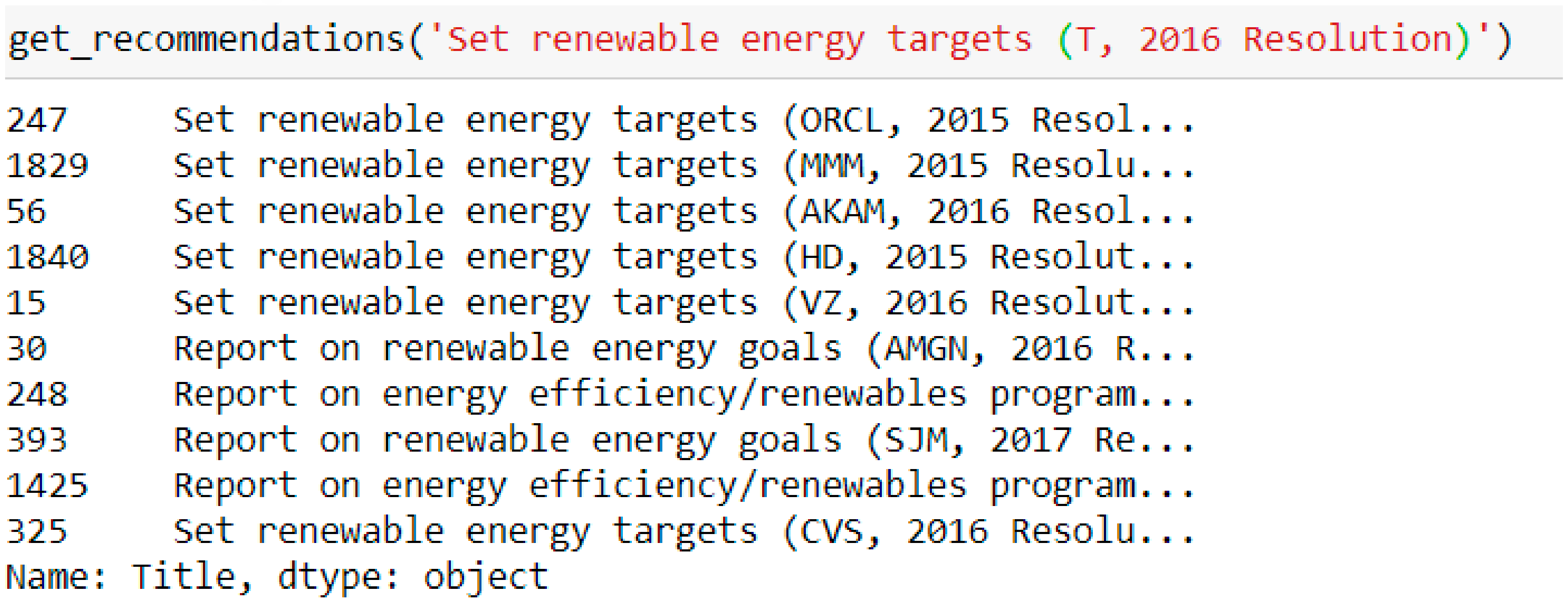

3.2. Text Analytics

4. Results and Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revising the Relation between Environmental Performance and Environmental Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Acc. Organ Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. ESG in Focus: The Australian Evidence. J. Bus. Ethic 2012, 118, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A. Identification and prioritization of corporate sustainability practices using analytical hierarchy process. J. Model. Manag. 2015, 10, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2007, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, H. Corporate social and environmental performance: A comparative study of Indonesian companies and multinational companies (MNCs) operating in Indonesia. J. Knowl. Glob. 2008, 1, 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A. Corporate sustainability performance and firm performance research literature review and future research agenda. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A.; Clarke, T.; Boersma, M. The Governance of Corporate Sustainability: Empirical Insights into the Development, Leadership and Implementation of Responsible Business Strategy. J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 122, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Yau, F.S.; San, O.T.; Attan, H. A Review on Green Integration into Management Control System. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F.; Journeault, M. Eco-control: The influence of management control systems on environmental and economic performance. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Frost, G.R. Accessibility and functionality of the corporate website: Implications for sustainability reporting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2006, 15, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, F.; Knirsch, M. Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility metrics for sustainable performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.-F.; Sheu, H.-J. Is Corporate Sustainability a Value-Increasing Strategy for Business? Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Raghupathi, W. Corporate Sustainability Reporting and Disclosure on the Web. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 32, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, G.; Peeters, R. Corporate Sustainability Performance and Assurance on Sustainability Reports: Diffusion of Accounting Practices in the Realm of Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 25, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnc, D.; Glavic, P. A model for integrated assessment of sustainable development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2005, 43, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Murty, H.; Gupta, S.; Dikshit, A.K. Development of composite sustainability performance index for steel industry. Ecol. Indic. 2007, 7, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Holmlund, M. Impression management tactics in sustainability reporting. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; Heenetigala, K. Integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure for a Sustainable Development: An Australian Study. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of the 21st Century; New Society Publishers: Stoney Creek, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, F.M.; Binder, J.K. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Convergent Process Model. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli, J.; Hartsuiker, D. World culture and transnational corporations: Sketch of a project. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Effects of and Responses to globalization, Istanbul, Turkey, 31 May–1 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, C.; Elkhawas, D. Corporate sustainability ratings: An investigation into how corporations use the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 35, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlieb, M.; Teuteberg, F. Corporate social responsibility reporting—A transnational analysis of online corporate social responsibility reports by market-listed companies: Contents and their evolution. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. A decade of sustainability reporting: Developments and significance. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.T.; Adhitya, A.; Srinivasan, R. Sustainability trends in the process industries: A text mining-based analysis. Comput. Ind. 2014, 65, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipziger, D. The Global Reporting Initiative. The Corporate Responsibility Code Book, 3rd ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2015; pp. 516–538. [Google Scholar]

- Székely, N.; Brocke, J.V. What can we learn from corporate sustainability reporting? Deriving propositions for research and practice from over 9,500 corporate sustainability reports published between 1999 and 2015 using topic modelling technique. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolk, A. Trends in sustainability reporting by the Fortune Global 250. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2003, 12, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørn, A.; Bey, N.; Georg, S.; Røpke, I.; Hauschild, M. Is Earth recognized as a finite system in corporate responsibility reporting? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 163, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modapothala, J.R.; Issac, B. Evaluation of Corporate Environmental Reports Using Data Mining Approach. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Technology, Singapore, 22–24 January 2009; Volume 2, pp. 543–547. [Google Scholar]

- Modapothala, J.R.; Issac, B.; Jayamani, E. Appraising the Corporate Sustainability Reports—Text Mining and Multi-Discriminatory Analysis. Innov. Comp. Sci. Softw. Eng. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, A.M.; Issac, B.; Modapothala, J.R. Analysis of supervised text classification algorithms on corporate sustainability reports. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology, Harbin, China, 24–26 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, A. A new politics of engagement: Shareholder activism for corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2003, 12, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. Two Sides of the Coin: Shareholders Engaging Companies on Sustainability Issues/Companies Promoting CSR Leadership as Good Business. J. Invest. 2011, 20, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenec, F. The “greening” of the annual letters published by Exxon, Chevron and BP between 2003 and 2009. J. Commun. Manag. 2012, 16, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. How does corporate social responsibility benefit firms? Evidence from Australia. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2010, 22, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. The Economic Relevance of Environmental Disclosure and its Impact on Corporate Legitimacy: An Empirical Investigation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2013, 24, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Uysal, N.; Taylor, M. Unleashing the Power of Networks: Shareholder Activism, Sustainable Development and Corporate Environmental Policy. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 27, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, S.; Edwards, M.; Williams, T. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Atan, R.; Alam, M.; Said, J.; Zamri, M. The impacts of environmental, social, and governance factors on firm performance. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Cin, B.C.; Lee, E.Y. Environmental Responsibility and Firm Performance: The Application of an Environmental, Social and Governance Model. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 25, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarmuji, I.; Maelah, R.; Tarmuji, N.H. The Impact of Environmental, Social and Governance Practices (ESG) on Economic Performance: Evidence from ESG Score. Int. J. Trade Econ. Finance 2016, 7, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, Y.; Ellison, J.; Ridgeway, R. The sustainable economy. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Harjoto, M.A.; Jo, H.; Kim, Y. Is Institutional Ownership Related to Corporate Social Responsibility? The Nonlinear Relation and Its Implication for Stock Return Volatility. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 146, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, L.; Moen, J. Sustainability in forest management and a new role for resilience thinking. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 310, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikken, B.J. Accelerating the Transition Towards Sustainable Investing—Strategic Options for Investors, Corporations, and Other Key Stakeholders. World Econ. Forum 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting. SSRN Electron. J. 2011, 11–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Ceballos, J.D. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Vithayathil, J.; Yim, D. Are corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives such as sustainable development and environmental policies value enhancing or window dressing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S. The development of corporate responsibility/corporate citizenship. Organ. Manag. J. 2008, 5, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A.S. Shareholder Activism on Sustainability Issues. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.; Nazari, J.A.; Mahmoudian, F. Stakeholder Relationships, Engagement, and Sustainability Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 138, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-D.P.; Lounsbury, M. Domesticating Radical Rant and Rage: An Exploration of the Consequences of Environmental Shareholder Resolutions on Corporate Environmental Performance. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, J. What We Want this Journal to Be: Our First Editorial Essay in which We Hope to Start a Continuing and Evolving Conversation about Why We are Now Creating this New Journal and What We Want It to Become. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain. 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Lülfs, R. Legitimizing Negative Aspects in GRI-Oriented Sustainability Reporting: A Qualitative Analysis of Corporate Disclosure Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 123, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I. Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability separate pasts, common futures. Org. Environ. 2008, 21, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azapagic, A.; Perdan, S. Managing corporate social responsibility: Translating theory into business practice. Int. J. Corp. Sustain. 2003, 10, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Belu, C. Ranking corporations based on sustainable and socially responsible practices. A data envelopment analysis (DEA) approach. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Scheermesser, M. Approaches to corporate sustainability among German companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, B.A.; Burnett, S.E.; Dennis, J.H.; Lopez, R.G. Growers look at operating a sustainable greenhouse. GMPro 2008, 28, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. Sustainable viticulture and winery practices in California: What is it, and do customers care? Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 2, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S.-C. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Hill, M.; Gollan, P. The sustainability debate. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, R.; Othman, R. Sustainability Practices and Corporate Financial Performance: A Study Based on the Top Global Corporations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 108, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.J.; Dennis, J.; Lopez, R.G.; Marshall, M.I. Factors Affecting Growers’ Willingness to Adopt Sustainable Floriculture Practices. HortScience 2009, 44, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, S.; Recker, J.; Pimmer, C.; vom Brocke, J. Enablers and barriers to the organizational adoption of sustainable business practices. In Proceedings of the 16th Americas Conference on Information Systems: Sustainable IT Collaboration around the Globe, Lima, Peru, 12–15 August 2010; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bizjak, J.M.; Marquette, C.J. Are Shareholder Proposals All Bark and No Bite? Evidence from Shareholder Resolutions to Rescind Poison Pills. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1998, 33, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, J.M.; Van Buren, H.J. Beyond the Proxy Vote: Dialogues Between Shareholder Activists and Corporations. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 87, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, H.G. Shareholder Social Proposals Viewed by an Opponent. Stanf. Law Rev. 1972, 24, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.B.; Waddock, S.; Rehbein, K. Fad and Fashion in Shareholder Activism: The Landscape of Shareholder Resolutions, 1988–1998. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2001, 106, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D. Trends in Shareholder Activism: 1970–1982. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 25, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancato, C.K. Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance: Beat Practices for Increasing Corporate Value; McGraw-Hill: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, M. Contests for Corporate Control: Corporate Governance and Economic Performance in the U.S. and Germany; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Monks, R.A.G.; Minnow, N. Power and Accountability; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, G.; Vogel, D. Lobbying the Corporation: Citizen Challenges to Business Authority. Politi-Sci. Q. 1979, 94, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Investment Forum (SIF). Report on Socially Responsible Investing Trends in the United States; SIF Industry Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.griequity.com/resources/InvestmentIndustry/Trends/siftrensreport2001.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Ryan, L.V. Shareholders and the Atom of Property: Fission or Fusion? Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, E.J.M. Effective Shareholder Engagement: The Factors that Contribute to Shareholder Salience. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.A.; Pound, J. Information, ownership structure, and shareholder voting: Evidence from shareholder-sponsored corporate governance proposals. J. Financ. 1993, 48, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpoff, J.M.; Malatesta, P.H.; Walkling, R.A. Corporate governance and shareholder initiatives: Empirical evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 1996, 42, 365–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.J. Rule 14a-8, institutional shareholder proposals, and corporate democracy. Ga. L. Rev. 1988, 23, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Taub, S. Shareholder Social Proposals Gain. 2004. Available online: https://www.cfo.com/risk-compliance/2004/09/shareholder-social-proposals-gain/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Allen, D.; Alves, L.; Caruncho, G.; Chin, D.; Cohn, D.; Damle, B.; Dracos, B.; Friend, S.; Ha, J.; Kadar, A.; et al. The New Science of Personalized Medicine. Available online: http://www.PWC.com (accessed on 20 August 2012).

- Meznar, M.B.; Nigh, D.; Kwok, C.C.Y. Effect of announcements of withdrawal from South Africa on stockholder wealth. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, E.M.; Toffel, M.W. Responding to public and private politics: Corporate disclosure of climate change strategies. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sachs, S. Managing the Extended Enterprise: The New Stakeholder View. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J.; Logsdon, J.M.; Lewellyn, P.G. Global Business Citizenship: A Transformative Framework for Ethics and Sustainable Capitalism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Masud, A.K.; Rashid, H.U.; Khan, T.; Bae, S.M.; Kim, J.D. Organizational Strategy and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Mediating Effect of Triple Bottom Line. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, S.; Zulkifli, N.; Zainal, D. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and Investment Decision in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, N.; Rahman, A.R.A.; Molla, R.I.; Noman, A.H.M.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.H. Is corporate social responsibility pursuing pristine business goals for sustainable development? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.M.; Masud, A.K.; Kim, J.D. A Cross-Country Investigation of Corporate Governance and Corporate Sustainability Disclosure: A Signaling Theory Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eesley, C.; Lenox, M.J. Firm responses to secondary stakeholder action. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, B.; Lee, L.H.; Khan, K. A Review of Machine Learning Algorithms for Text-Documents Classification. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2010, 1, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, J.; Zuell, C. Identifying Events Using Computer-Assisted Text Analysis. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2007, 26, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, M.; Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1984, 79, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Ren, J.; Raghupathi, W. Studying Public Perception about Vaccination: A Sentiment Analysis of Tweets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghupathi, V.; Zhou, Y.; Raghupathi, W. Legal Decision Support: Exploring Big Data Analytics Approach to Modeling Pharma Patent Validity Cases. IEEE Access. 2018, 6, 41518–41528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Zhou, Y.; Raghupathi, W. Exploring Big Data Analytic Approaches to Cancer Blog Text Analysis. Int. J. Healthc. Inf. Syst. Inf. 2019, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceres. 2020. Available online: https://www.ceres.org/resources/tools/climate-and-sustainability-shareholder-resolutions-database (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Cook, J. Political action through environmental shareholder resolution filing: Applicability to Canadian Oil Sands? J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2012, 2, 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Monks, R.; Miller, A.; Cook, J. Shareholder activism on environmental issues: A study of proposals at large US corporations (2000–2003). Nat. Resour. Forum 2004, 28, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, T.M. Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. The CERES principles: A voluntary code for corporate environmental responsibility. Yale J. Int. Law 1993, 18, 307. [Google Scholar]

- Dietterich, T.G. Machine learning in ecosystem informatics and sustainability. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Pasadena, CA, USA, 14–17 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, C.H.; Song, W.; Liu, S. Machine Learning Algorithms with Co-occurrence Based Term Association for Text Mining. In Proceedings of the 2012 Fourth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks, Mathura, India, 3–5 November 2012; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 958–962. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, J. Using TF-IDF to Determine Word Relevance in Document Queries; Technical Report; Department of Computer Science, Rutgers University: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M. Here Is the Letter the World’s Largest Investor, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, Just Sent to CEOs Everywhere. 2016. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/blackrock-larry-fink-letter-to-ceos-2017-1 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

| No. | Rank | Company | Count | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Exxon Mobil Corporation | 53 | 3.05% |

| 2 | 2 | Chevron Corporation | 45 | 2.59% |

| 3 | 3 | Dominion Energy, Inc. | 29 | 1.67% |

| 4 | 4 | Amazon.com Inc. | 20 | 1.15% |

| 5 | 4 | ConocoPhillips | 20 | 1.15% |

| 6 | 6 | Alphabet Inc. | 19 | 1.09% |

| 7 | 6 | Devon Energy Corporation | 19 | 1.09% |

| 8 | 6 | McDonald’s Corp. | 19 | 1.09% |

| 9 | 9 | Duke Energy Corporation | 16 | 0.92% |

| 10 | 9 | Kroger Co. | 16 | 0.92% |

| 11 | 11 | Emerson Electric Co. | 14 | 0.81% |

| 12 | 11 | FedEx Corporation | 14 | 0.81% |

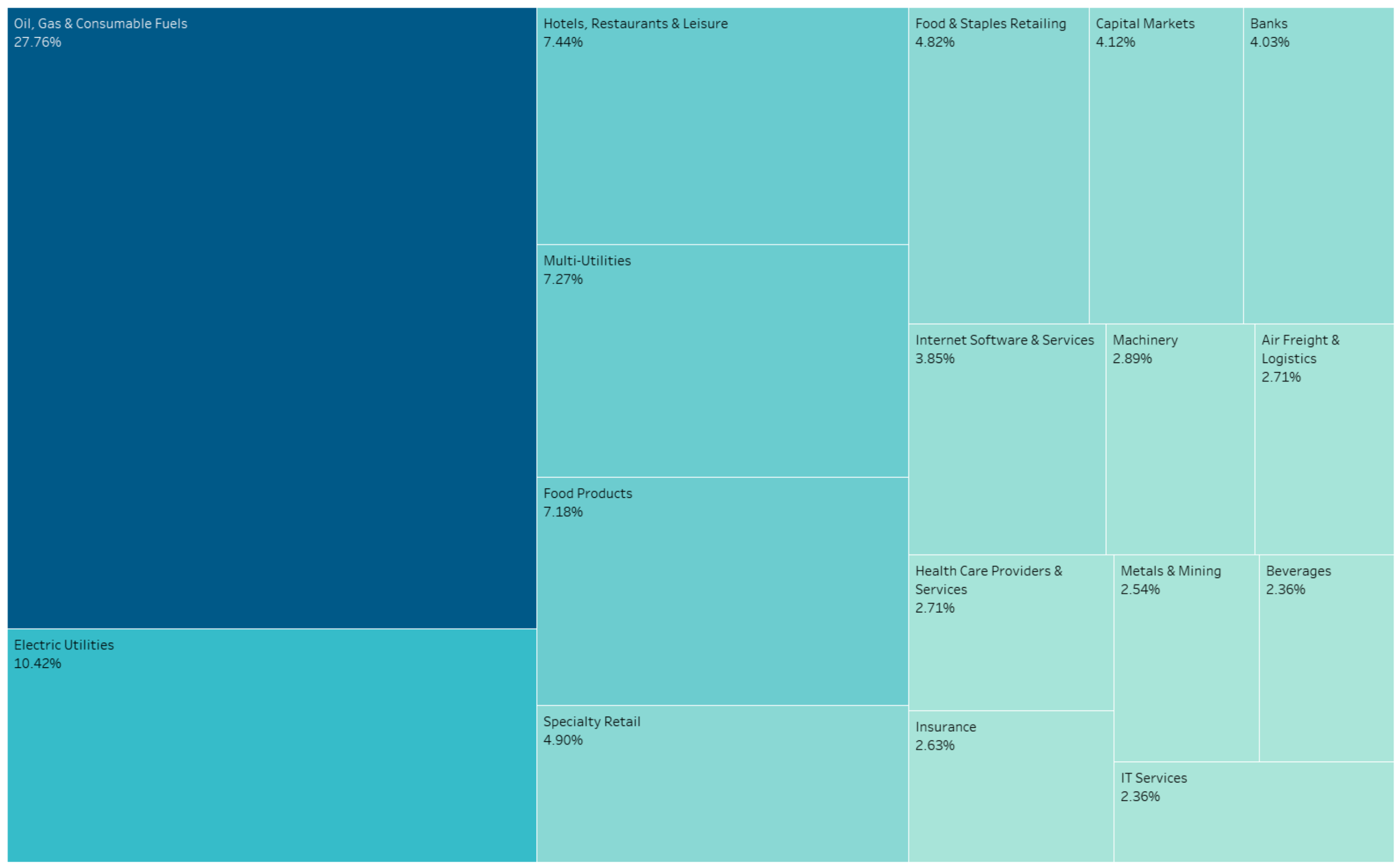

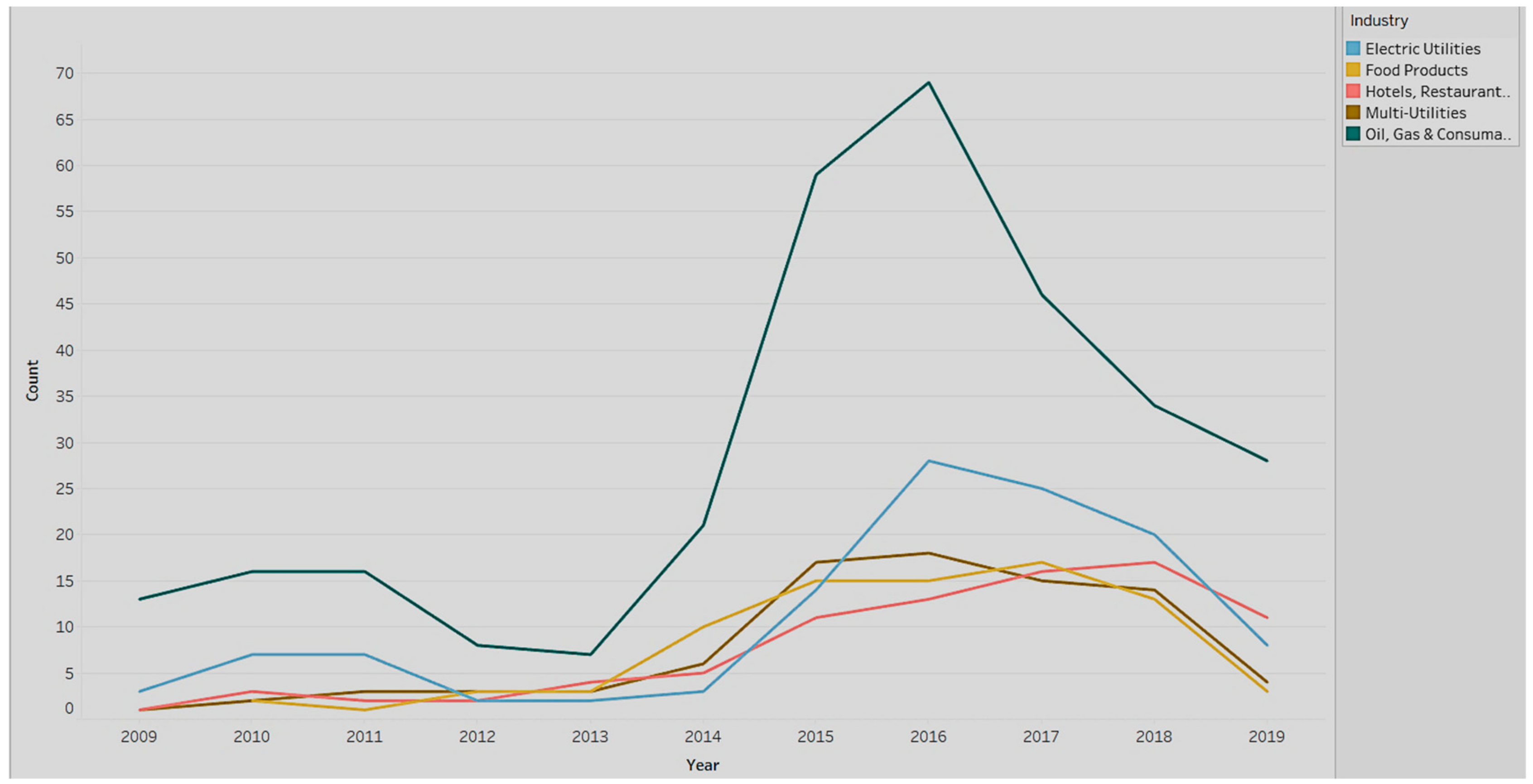

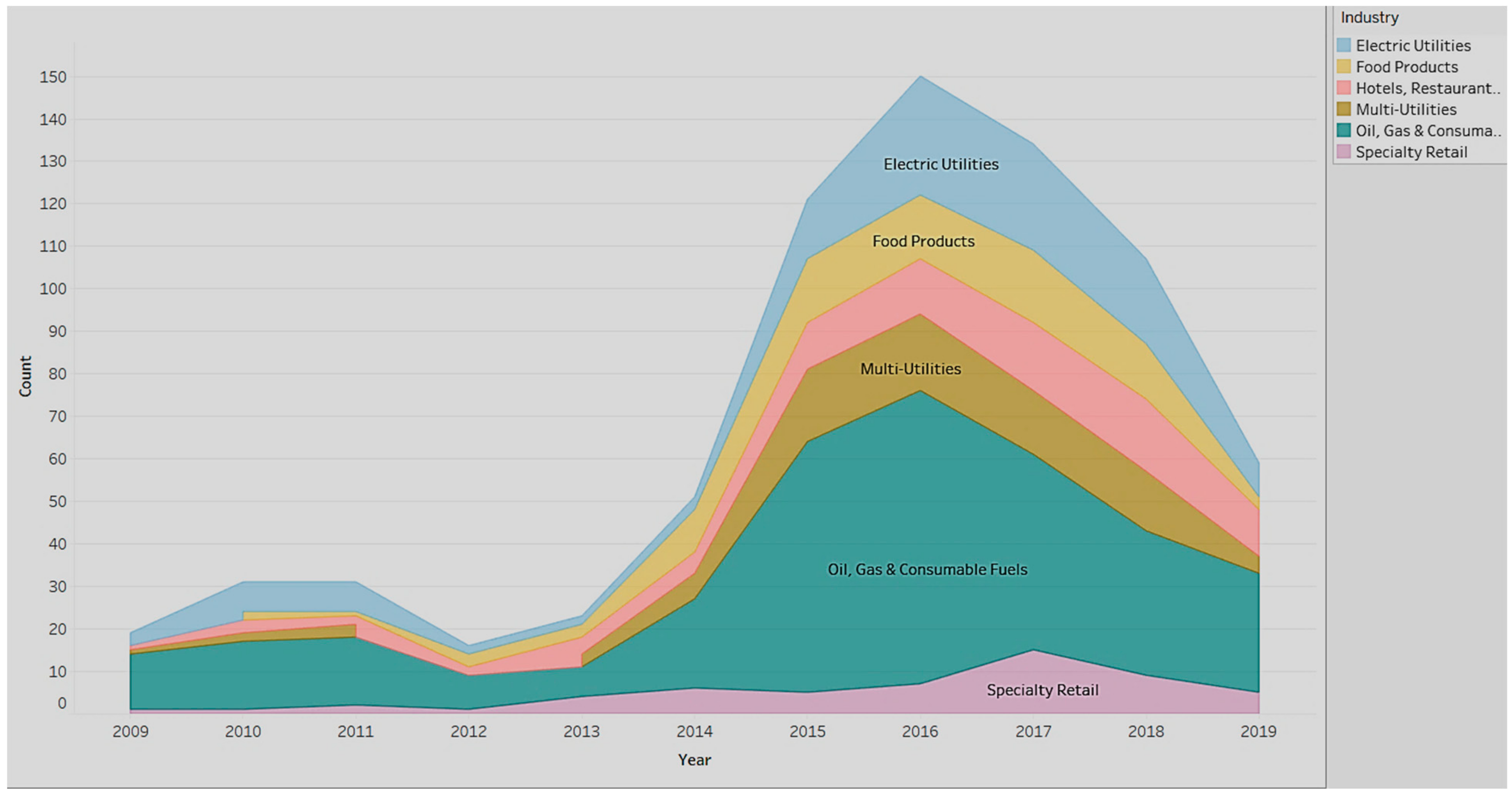

| Rank | Sector | Count | Rank | Sector | Count |

| 1 | Oil, Gas & Consumable Fuels | 317 | 16 | IT Services | 27 |

| 2 | Electric Utilities | 119 | 18 | Biotechnology | 26 |

| 3 | Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure | 85 | 18 | Chemicals | 26 |

| 4 | Multi-Utilities | 83 | 18 | Equity Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) | 26 |

| 5 | Food Products | 82 | 18 | Internet & Direct Marketing Retail | 26 |

| 6 | Specialty Retail | 56 | 18 | Media | 26 |

| 7 | Food & Staples Retailing | 55 | 23 | Diversified Telecommunication Services | 25 |

| 8 | Capital Markets | 47 | 24 | Multiline Retail | 24 |

| 9 | Banks | 46 | 25 | Communications Equipment | 23 |

| 10 | Internet Software & Services | 44 | 25 | Pharmaceuticals | 23 |

| 11 | Machinery | 33 | 27 | Tobacco | 22 |

| 12 | Air Freight & Logistics | 31 | 28 | Textiles, Apparel & Luxury Goods | 21 |

| 12 | Health Care Providers & Services | 31 | 29 | Aerospace & Defense | 20 |

| 14 | Insurance | 30 | 29 | Health Care Equipment & Supplies | 20 |

| 15 | Metals & Mining | 29 | 29 | Technology Hardware, Storage & Peripherals | 20 |

| 16 | Beverages | 27 | 32 | Electrical Equipment | 19 |

| Rank | Sector | Count | Rank | Sector | Count |

| 33 | Industrial Conglomerates | 18 | 49 | Auto Components | 5 |

| 34 | Construction & Engineering | 17 | 50 | Professional Services | 4 |

| 34 | Software | 17 | 50 | Real Estate Management & Development | 4 |

| 36 | Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment | 16 | 52 | Airlines | 3 |

| 37 | Automobiles | 15 | 52 | Building Products | 3 |

| 37 | Household Products | 15 | 52 | Construction Materials | 3 |

| 39 | Diversified Financial Services | 14 | 52 | Containers & Packaging | 3 |

| 39 | Energy Equipment & Services | 14 | 52 | Electronic Equipment, Instruments & Components | 3 |

| 39 | Independent Power and Renewable Electricity Producers | 14 | 52 | Life Sciences Tools & Services | 3 |

| 42 | Road & Rail | 13 | 52 | Personal products | 3 |

| 43 | Consumer Finance | 12 | 52 | Trading Companies & Distributors | 3 |

| 44 | Gas Utilities | 10 | 60 | Diversified Consumer Services | 2 |

| 45 | Commercial Services & Supplies | 9 | 60 | Wireless Telecommunication Services | 2 |

| 46 | Household Durables | 7 | 62 | Distributors | 1 |

| 46 | Water Utilities | 7 | 62 | Mortgage Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) | 1 |

| 48 | Leisure Products | 6 | 62 | Paper & Forest Products | 1 |

| Year | Status | Count | Year | Status | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Others | 6 | 2015 | Others | 9 |

| Vote | 24 | Vote | 207 | ||

| Withdrawn | 17 | Withdrawn | 46 | ||

| 2009 Total | 47 | 2015 Total | 262 | ||

| 2010 | Others | 4 | 2016 | Others | 10 |

| Vote | 41 | Vote | 245 | ||

| Withdrawn | 27 | Withdrawn | 59 | ||

| 2010 Total | 72 | 2016 Total | 314 | ||

| 2011 | Others | 6 | 2017 | Others | 15 |

| Vote | 17 | Vote | 227 | ||

| Withdrawn | 23 | Withdrawn | 87 | ||

| 2011 Total | 46 | 2017 Total | 329 | ||

| 2012 | Others | 5 | 2018 | Others | 34 |

| Vote | 14 | Vote | 207 | ||

| Withdrawn | 12 | With drawn | 91 | ||

| 2012 Total | 31 | 2018 Total | 332 | ||

| 2013 | Others | 2 | 2019 | Others | 88 |

| Vote | 14 | Vote | 5 | ||

| Withdrawn | 44 | Withdrawn | 43 | ||

| 2013 Total | 60 | 2019 Total | 136 | ||

| 2014 | Others | 12 | |||

| Vote | 33 | ||||

| Withdrawn | 63 | ||||

| 2014 Total | 108 | Grand Total | 1737 |

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Org | Organization |

| Industry | The industry in which the organization operates |

| Title | The title of the sustainability disclosure |

| Filed By | The entity whom filed the disclosure for the organization |

| Status | Vote/Others/Withdraw |

| Label | Vote=1/Others=2/Withdraw=O |

| Y | Filling year of the disclosure |

| Summary | Textual disclosure of such report |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raghupathi, V.; Ren, J.; Raghupathi, W. Identifying Corporate Sustainability Issues by Analyzing Shareholder Resolutions: A Machine-Learning Text Analytics Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114753

Raghupathi V, Ren J, Raghupathi W. Identifying Corporate Sustainability Issues by Analyzing Shareholder Resolutions: A Machine-Learning Text Analytics Approach. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114753

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaghupathi, Viju, Jie Ren, and Wullianallur Raghupathi. 2020. "Identifying Corporate Sustainability Issues by Analyzing Shareholder Resolutions: A Machine-Learning Text Analytics Approach" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114753

APA StyleRaghupathi, V., Ren, J., & Raghupathi, W. (2020). Identifying Corporate Sustainability Issues by Analyzing Shareholder Resolutions: A Machine-Learning Text Analytics Approach. Sustainability, 12(11), 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114753