1. Introduction

Sewage sludge is an end-product of primary and secondary treatments of sewage effluent arising from urban sources and may contain high concentrations of heavy metals and persistent synthetic organic compounds, depending on its origin [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, careless dumping of municipal sewage sludge (MSS) to the sea has resulted in serious marine pollution and has raised concerns about the damage to the marine environment and potential safety threats [

5,

6]. In addition, there has been growing awareness that instead of disposal of sewage sludge, it can be recycled.

With the increasing demand for international regulation, the practice of ocean dumping of sewage sludge has been banned in Europe since 1998 by the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North–East Atlantic, and the London Protocol (hereafter, LP) came into effect in 2006. The LP was organized to protect the marine environment from human activities under the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and it has focused on a precautionary approach to environmental protection from the dumping of waste or other materials [

7,

8]. The Republic of Korea (hereafter, ROK) joined the London Convention (hereafter, LC) on December 21, 1993, and the LP that was agreed in 1996 to further modernize and eventually to replace the LC, on January 22, 2009. The Ministry of Ocean and Fisheries (hereafter, MOF) of ROK administers the ocean dumping of wastes, including MSS, under the Marine Environmental Management Act to meet the international obligations under the LP. In pursuing the precautionary principles of the LP, the MOF recognized that using MSS as a resource instead of just dumping it into the sea could be a more effective approach. Therefore, it has aggressively promoted the policy with efforts to minimize conflicts with stakeholders.

In July 2016, the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (hereafter, KIOST) of ROK submitted a report to the office of the London Convention and London Protocol (hereafter, LC/LP) with the title of “Barriers to compliance with the termination of the ocean dumping of sewage sludge in the Republic of Korea” [

9]. In the report, ROK introduced a legal system and background for phasing out the ocean dumping of MSS before the establishment of the policy in 2012. Furthermore, it introduced the progress of the policy on the establishment of annual reduction goals, action levels to improve the efficiency of the policy, a surveillance system to observe illegal dumping, monitoring outcomes, management plans, and public activities with the cooperation of governmental agencies.

A study of similar analysis can be found in Swanson et al. [

10], in which the lessons learned from the practice of ocean dumping of sewage sludge in New York City since the early 20

th century was reviewed to provide understanding of the long-term effect of policies that had been piecemeal and changed according to shifting circumstances. Ocean dumping of sewage began in New York City in 1924 at the 12–Mile Site, and it moved to the 106–Mile Site in 1986. In response to political pressure, the practice of ocean dumping ended entirely in 1992. The study revealed that, although it was cheaper than other disposal methods, ocean dumping of sewage sludge could deteriorate the benthic environment in a wide area around the dumping site. In addition, Ofira [

11] introduced efforts and outcomes to clean up the contaminated beaches along the coastlines of New York and New Jersey as a result of the NY Bight Restoration Plan. The results suggested that although progress was made successfully, policy directives may need to be refined based on the current situation. For example, initial objectives to ensure that no beaches are closed during the summer season may not be achievable based on the research data on environmental contamination, and thus an amendment to these policies may be required.

Similarly, the objective of this review is to examine the policies and outcomes concerning phasing out the ocean dumping of sewage sludge in ROK and to share its experience with countries in overcoming barriers to LP compliance in tandem with a previous report submitted to the office of the LP [

9]. We provide additional data on the outcomes of the phasing out policy and compare the statistics between the ocean dumping and landfills of MSS to show the efficiency of the administrative actions. In addition, follow-up measures taken after 2016 are introduced, including extended monitoring and management results. This study’s findings can provide useful information for the future development of long-term strategies and policies for minimizing ocean dumping and protecting the marine environment in coastal seas. Specifically, we suggest a method for improving the contaminated benthic environment at a dumping site based on statistical results, with specific conditions on where direct dredging was not feasible because of the distance from the shore and the water depth; this approach may be effectively applied to areas with similar circumstances.

2. Literature/Policy Review

2.1. Summary of 2016 Report to Office of LP

In this section, the previous report submitted to the office of the LP in 2016 [

9] is summarized by briefly introducing the progress and outcome of the MOF’s administrative policy to phase out the ocean dumping of sewage sludge in the ROK up to 2016. This summary is necessary for readers to understand the background of the policy and its progress, as the previous report is not easily accessible. Furthermore, the summary can be used to understand the additional statistics and measures provided in this review.

Background

The ROK began ocean dumping in 1993 to reduce the load of waste produced on land and to prevent excessive degradation of river and coastal environments [

12]. Consequently, the Waste Management Act pronounced a ban on the direct landfilling of MSS in 1997 and went into effect in 2006. However, these legal measures caused substantial amounts of MSS to be diverted from land filling to ocean dumping. The dumping of MSS to the sea commenced in 1993, with a sharp build-up in quantity from approximately 10 × 10

3 m

3 to 8812 × 10

3 m

3 in 2006.

As a consequence of this increased influx of MSS, substantial enrichments were observed for trace metals including Cr, Cd, and Pb in the surficial dump site sediments, and this has affected the distributional patterns of benthic species in dump sites [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The habitats at these dump sites have been negatively impacted by anthropogenic activities, resulting in considerable changes to the structure of these ecosystems. This led to widespread awareness of environmental damage caused by the ocean dumping of MSS that evolved into a major social crisis, producing intense social conflicts, which provided a key motivation for establishing the policy to phase out ocean dumping of MSS [

12].

Internationally, a common trend has been to enact waste treatment policies in the order of most-to-least impactful on the environment by allowing ocean dumping only when inland treatment/disposal methods are not available. In this context, most contracting parties of the LP had banned the ocean dumping of MSS prior to the year 2000, as the LP requires that the hierarchy of waste management options be followed according to increasing environmental impact; this reality encouraged the MOF to prepare relevant policies and regulations concerning marine environment protection.

2.2. Progress of the Phase-Out Policy

2.2.1. Annual Reduction Goal

MOF prepared the implementation of the LP in the ROK by arranging regulations for ocean dumping of MSS in 2006; specifically, the MOF promulgated a revised enforcement rule for the Marine Environment Management Act. The MOF then established the Master Plan of Ocean Dumping Management, and it was approved by the Cabinet Council in March 2006. The plan focused on strengthening the restriction of ocean dumping of wastes by establishing a principle of land-based priority treatment and a scientific system of environmental management of dumping sites. This plan aimed to reduce the ocean dumping of MSS through inter-agency consultations and professional advice on the status of inland treatment/disposal. The plan also set a goal in 2006 to reduce the annual amount of MSS dumped into the sea by 50% by 2011, as listed in

Table 1.

To achieve this goal, MOF strengthened the standards of ocean dumping pollution by introducing the “polluter-pays principle”, by which the party responsible for producing pollution is responsible for paying for the damage done to the natural environment. This policy is enforced by conducting monitoring at dump sites on a regular basis, monitoring illegal activities by dumping vessels by strengthening cooperation with other organizations, and by building consensus among stakeholders. Consequently, the amount of ocean dumping of MSS has continuously decreased by more than 10% per year and the actual amount of ocean dumping in 2011 just before the ban of ocean dumping of MSS in 2012 was 3.97 million m3, which was less than the targeted value (4 million m3). Since 2012, the amount has been zero until 2019.

2.2.2. Action Levels

The maximum permissible contents of contaminants that can be dumped into the sea have been set as action levels by the LP (IMO) waste assessment guidelines [

7]). The action levels have effectively served as policy measures that have assisted in reducing the demand for ocean dumping of MSS, and pollution loads, and for mitigating pollution at dumping sites. Furthermore, these measures have been useful in reducing the amount of waste by converting it to recycling materials. In

Table 2, the rates of recycling, landfill, incineration and ocean dumping out of the total mass of sewage sludge is compared between 2005 and 2012, which shows that energy efficiency was greatly enhanced due to the reduction in ocean dumping.

Based on the LP’s guidelines, the MOF also developed its own action levels that provide criteria for permissible contaminants by analyzing sewage sludge in more than one hundred sewage treatment plants in the ROK (

Table 2). The upper and lower limits of the permissible contents of the harmful substances in the list have served as a useful basis to determine how much of those substances could be safely contained in the ocean (

Table 3). Using the action levels based on LP guidelines, the wastes were categorized into three groups before deciding their suitability for ocean dumping as follows:

Upper level: wastes that exceed maximum levels of permissible contents shall not be dumped to avoid acute or chronic effects on human health or impacts on sensitive marine organisms that are representative of the marine ecosystem.

Lower level: wastes that are below minimal levels of permissible contents are of little environmental concern in relation to dumping.

Wastes that are in between the lower and upper limits require more detailed assessments such as toxicity tests before determining their suitability for dumping.

Contractor companies should improve their capacity to purify sewage sludge to satisfy these criteria. Following international standards, luminous bacteria and benthic amphipods were used for toxicity tests, and only the MSS that passed the test criteria has been permitted for ocean dumping since 2008. In case of failure, the sludge should be treated or disposed of on land. The failure rates in the tests increased and became similar to the rate of reduction in the amount of MSS dumped in the ocean, and its amount in 2011 became half of that in 2005.

2.2.3. Polluter-Pays Approach

The main reason that ocean dumping of sewage sludge was preferred to inland treatment/disposal methods was the minimal cost [

10]. Therefore, the amount of ocean dumping can be controlled if the responsibility of the dumping party is increased in case of pollution; this summarizes the practical application of the LP’s “polluter-pays principle”. Perceiving its efficiency, the MOF also applied the principle by amending the Marine Environment Management Act to impose charges on ocean dumping of sewage sludge starting in 2006. The charge would increase if the dumping sewage sludge contained high concentrations of contaminants, and the imposed charges were deposited to the fisheries development fund that is used for marine environment improvement.

2.3. Surveillance

Occasionally, illegal dumping would occur, as the sewage sludge was disposed outside the designated sites to reduce the transportation cost. For example, a total of 188 cases were detected that violated ocean dumping standards from 2005 to 2007 in the ROK. To inspect such violations, MOF developed the automatic identification system (AIS) by which the navigation status of waste transport vessels could be tracked using GPS. The illegal dumping of sewage sludge could be detected by the Korean Coast Guard by monitoring the locations and traces of the vessels, and all waste transport vessels have been equipped with AIS since 2008 to prevent illegal practices.

In accordance with this surveillance regime, appropriate monitoring of waste dump sites has become an important approach, because environmental impacts from ocean dumping of sewage sludge are severe and long-lasting [

19]; moreover, the LP requires monitoring of waste dump sites as a precautionary approach. Since 2004, KIOST has conducted annual monitoring at designated dumping sites in which their environmental conditions are evaluated and remedies are proposed if problems are detected. The results from the monitoring have been utilized to minimize damages to the marine environment through the construction of regulations on waste dumping in these sea areas, with the ultimate goal of restoring the contaminated areas. Since 2006, for example, ocean dumping activities have been banned in some sectors of dump sites that have suffered from concentrated contamination; accordingly, they were designated for restoration based on KIOST’s monitoring results [

16].

2.4. Intergovernmental Coordination and Consensus Building

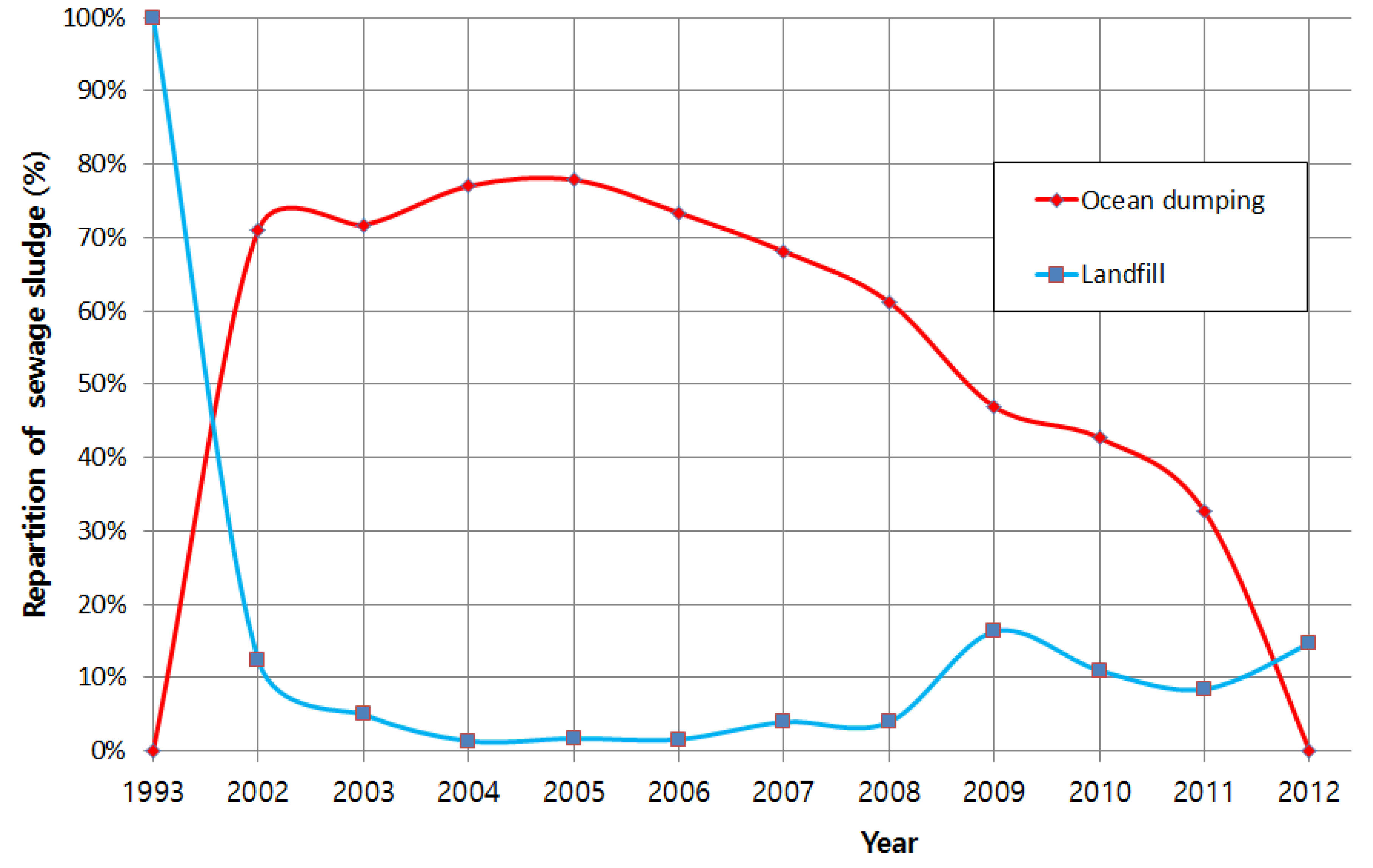

Until 2005, the amount of ocean dumping of MSS in the ROK rapidly increased, and the most common reason for this was the enhanced regulatory control on inland waste treatment/disposal methods that left ocean dumping as the only viable option. For instance, the Ministry of Environment of ROK announced a ban on the landfill of sewage sludge in 1997, which had resulted in a sharp increase in the ocean dumping of MSS from 1996 until 2005, when the ban came into effect.

Figure 1 compares the annual variation of the MSS amounts dumped in the ocean and sent to landfills. The amount of landfilled sewage sludge sharply decreased from 1993–2005, which was due to the banning of landfills by the Waste Management Act as pronounced in 1997 and implemented in 2006.

Thus, to reduce the ocean dumping of land-based wastes, cooperation was necessary between corresponding governmental agencies in reducing in both land- and ocean-based wastes. The MOF started a task force team to collect data on the amount of MSS produced in each local district and their present treatment conditions to establish future plans through cooperation with other governmental agencies and by conducting field studies at the treatment facilities. In 2006, the Master Plan of Ocean Dumping Management was established and implemented based on the data collected by the team.

The consensus and active participation of the public and stakeholders is an important ingredient in the successful implementation of phasing out the ocean dumping of MSS. For this purpose, the MOF determined the crucial issues that various stakeholders faced and held public hearings, making efforts to ensure compromises between them. Combining the data collected from the surveys made for the inland treatment/disposal and ocean dumping practices of the sewage sludge, the MOF concluded that a reduction in ocean dumping and ultimately phasing out the practice while increasing the number of the inland disposal facilities would result in stronger benefits for the country. In addition, the MOF published professional opinions with the help of KIOST through mass media, and reached out to the public through on-site education to understand the impact of marine pollution caused by ocean dumping of sewage sludge and thus to enhance citizens’ awareness.

2.5. Monitoring since 2016

Recognizing that the main reason for the increase in the ocean dumping of municipal sewage waste was the ban on landfills, the MOF closely cooperated with other government agencies and developed the Master Plan for Ocean Dumping Management in 2006. In addition, the MOF prepared regulations for the ROK to join the LP in 2009 so that its measures could be implemented nationally, which led to the establishment of the amendment to the Marine Environment Management Act in 2012. The effect of these sequential governmental actions was evident and immediate, as the amount of ocean dumping of MSS in the ROK became zero in 2012.

Although the ocean dumping of MSS was terminated in 2012, the MOF still allowed temporal dumping of sludge produced from private waste treatment plants, only when ocean dumping was inevitable. However, the MOF continued its efforts toward zero dumping of all kinds of sludge by gradually reducing the total amount of ocean dumping of sludge. As a result, the amount of total ocean dumping was 2016 × 10

3 m

3 in 2012 when the dumping of MSS was banned, and it was reduced to 900 × 10

3 m

3 in 2013 when the ocean dumping of food-oriented sewage sludge was banned. In 2014, the MOF implemented a certificate system to permit the dumping of other waste sludge; this has led to a dramatic reduction in the amount of sludge dumping, as it was 352 × 10

3 m

3 in 2014 and 154 × 10

3 m

3 in 2015. Finally, in 2016, all kinds of sewage sludge, including wastewater sludge, were banned for ocean dumping in accordance with the establishment of the policy of zero dumping of sewage sludge into the sea in the same year [

20].

The environmental conditions at designated dumping sites have improved continuously since 2016. However, they were still contaminated, as the heavy metal concentrations in some of these sites were higher than the threshold effect level (TEL) established by the MOF (

Figure 2b). Because the dumping sites were located far away from land and the water depths of the sites ranged from 80 m to 1000 m, the commonly used dredging method for remediating contaminated sediment was not feasible. Since 2016, the MOF has conducted scientific studies on remediating the contaminated sediments. Their results showed that the capping method was effective in achieving this goal [

17]. In this method, the contaminated sediments were covered with dredged materials as they were carried to the designated sites from the seashore by vessels.

In

Figure 2a,b, the concentration of chromium (Cr) is compared at selected stations in one of the designated dumping sites in the ROK. The concentration was measured in 2019, three years after the capping started in 2016. The stations were selected to compare the Cr concentrations between the capping area and the uncapping area, which was inside the dumping site but did not use capping, and the reference area, which was outside the dumping site and thus Cr concentration in the reference area could be used as a standard. Cr is one of the most serious contaminants and is contained in the sludge generated from leather factories. In the locations shown in

Figure 2a, the sludge produced in the wastewater disposal plants near leather factories was dumped and thus the Cr concentration could be used as a measure for contamination.

Notably, the Cr concentrations of two stations (U-1 and U-2) in the uncapping area were higher than TEL, thereby indicating the contamination was serious in these areas. However, the concentration in the capping area (C-1, C-2, and C3) was substantially lower than even in the reference area, which indicated the capping effectively remediated the contaminated sediments in the designated dumping site.

3. Discussion

This review reports the successful outcomes that resulted from the MOF’s policies and additionally provides insight for future planning under similar conditions. The initiation of ocean dumping of sewage sludge in the ROK was directly related to the ban of inland treatment/disposal. However, the cheap cost of ocean dumping also contributed to a substantial increase in its usage. Therefore, to reduce the amount of ocean dumping, careful investigation was required to build comprehensive planning that considered all the environmental, economic, and social effects on stakeholders and local communities.

The policies of the MOF that aimed to reduce ocean dumping were successfully applied in the seas of the ROK within a short period, as the Master Plan of Ocean Dumping Management was established in 2006 and the amount of ocean dumping of MSS became zero in 2012. The reason for this rapid success can be found in the application of economic actions such as the polluter-pays principle, which effectively worked for the stakeholders. These actions were strictly applied with fortified surveillance systems such as AIS. In addition, by setting the annual reduction goals of permitted sewage sludge, the amount of ocean dumping could be gradually reduced until it was finally terminated, which provided time for the dumping companies to prepare alternatives. The most successful outcomes in similar scenarios may be potentially achieved from close cooperation between government agencies. The MOF reduced the amount of ocean dumping by increasing the amount for recycling on land through an agreement based on research data and professional advice; additionally, this agreement created socio-economic benefits by encouraging the recycling industry. In addition, the MOF’s efforts to minimize conflicts between stakeholders and local communities were successful, as consensus and mutual understanding were reached through continuous education.

This paper focuses on the importance of follow-up monitoring and inspection of the dumping sites even after implementation of the policy and termination of the dumping activities. This is because the ultimate goal of these policies and actions of the government is to recover and maintain the environmental health of the nation. Therefore, studies focusing on determining the best ways to ensure effective policy implementation must be continuously performed to establish future plans or to amend existing policies, and their efficiency should be evaluated based on careful inspection. Regardless of the successful banning of sewage sludge, fish wastes, organic matter of natural origin, and dredged materials are still allowed for ocean dumping in the ROK, and these substances require close monitoring to examine their impacts on the marine environment. In addition, determinations of the environmental impacts of capping methods or determining alternative methods to recover contaminated areas are necessary for investigation of the future safety of the marine environment.

4. Conclusions

Ocean dumping of sewage sludge commenced in 1993 and rapidly increased until 2006 in the ROK as a result of the prohibition on landfills for sewage sludge, which increased negative impacts on the marine environment and raised societal concerns. To properly cope with these impacts, the MOF implemented the Master Plan of Ocean Dumping Management in which ocean dumping of sewage sludge was phased out from 2006 onwards. The MOF’s plans and corresponding actions were effective, as they led to termination of ocean dumping of MSS in 2012 and further reduction of the amount of other sludges in the following years until all types of sewage sludge were banned from ocean dumping in 2016. The efforts of the MOF to reduce the amount of ocean dumping have caused an extra effect in that they increased energy efficiency. For example, in 2005, one year before the MOF’s plan started, the rate of ocean dumping out of the total mass of sewage sludge in the ROK was 78%, which covered 3/4 of the total amount. In the same year, the rate of recycling of total sewage sludge was only about 5%. When ocean dumping was terminated in 2012, however, the rate of recycling increased to 43%. In addition, the use of energy from incineration and from the collected gas from reclamation significantly increased as well, which contributed to the successful application of the policy of the MOF.

Even though dumping activity was terminated, the MOF has continuously conducted monitoring and research at the dumping sites to understand the contamination process and developed methods to recover the environmental conditions at the sites. Although direct dredging at the dumping sites was not feasible because of the distance from the shore and the water depth, the capping method that covered dredged materials at the top of the area was effective in reducing the concentrations of harmful substances at dumping sites. The success of these policies in the ROK can be attributed to the rapid and strict application of policies with fortified surveillance, in addition to close intergovernmental cooperation and an achieved consensus between stakeholders and communities. However, consistent monitoring is required at the contaminated areas to develop future plans to recover the local marine environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.C., K.-Y.C., C.-J.K. and Y.S.C.; methodology, C.S.C., K.-Y.C. and C.-J.K.; investigation, C.S.C. and Y.S.C.; resources, C.S.C., K.-Y.C., J.-M.J. and C.-J.K.; data curation, C.S.C., K.-Y.C., J.-M.J. and C.-J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.C.; visualization, C.S.C., J.-M.J.; supervision, Y.S.C.; project administration, C.S.C.; funding acquisition, C.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF), grant number BSPG51041-12100-2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the officers and research team members who were involved in this study, especially those in the MOF and the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST). We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Song, G.H.; Choi, K.Y.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, Y.I.; Chung, C.S. Assessment of the governance system for the management of the East Sea-Jung dumping site, Korea through analysis of heavy metal concentrations in bottom sediments. Ocean Sci. J. 2015, 50, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.A.B.; de Carvalho, D.G.; Medeiros, K.; Drabinski, T.L.; de Melo, G.V.; Silva, R.C.O.; Diogo, S.; Leandro, B.; Gilberto, D.; dos Santos Filho, J.R.; et al. The impact of sediment dumping sites on the concentrations of microplastic in the inner continental shelf of Rio de Janeiro/Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Lei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Fang, H. Determining Discharge Characteristics and Limits of Heavy Metals and Metalloids for Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) in China Based on Statistical Methods. Water 2018, 10, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, T.; Mekonnen, A.; Leta, S. Integrated tannery wastewater treatment for effluent reuse for irrigation: Encouraging water efficiency and sustainable development in developing countries. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 30, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguello-Pérez, M.Á.; Mendoza-Pérez, J.A.; Tintos-Gómez, A.; Ramírez-Ayala, E.; Godínez-Domínguez, E.; Silva-Bátiz, F.A. Ecotoxicological Analysis of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater Discharges in the Coastal Zone of Cihuatlán (Jalisco, Mexico). Water 2019, 11, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Short, M.D.; Gerber, C.; Awad, J.; van den Akker, B.; Saint, C.P. Removal of emerging drugs of addiction by wastewater treatment and water recycling processes and impacts on effluent-associated environmental risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMO. Waste Assessment Guidelines under the London Convention and Protocol, Edition (IA531E). 2014. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/LCLP/Publications/wag/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 7 November 2014).

- Hong, G.H.; Lee, Y.J. Transitional measures to combine two global ocean dumping treaties into a single treaty. Mar. Policy 2015, 55, 47–56. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X15000184 (accessed on 16 January 2015). [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.H.; Chung, C.S. Barriers to Compliance with the Termination of the Ocean Dumping of Sewage Sludge in the Republic of Korea; Youngjin P&P: Seoul, Korea, 2016; p. 93. ISBN 978-89-444-9042-2. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.L.; Bortman, M.L.; O’Conner, T.P.; Stanford, H.M. Science, policy and the management of sewage materials. The New York City experience. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 49, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofira, D.D. The New York Bright years later: Use impairments and policy challenges. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 90, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.G.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Hyun, C.G.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, K.J. The condition and management measure of marine disposal of wastes. In Proceedings of the KOSOMES Biannual Meeting, 2006; pp. 109–115. Available online: http://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/CFKO200601436758450 (accessed on 16 March 2006).

- Lee, K.Y.; Chung, C.S.; Kim, Y.I.; Lee, H.K.; Hong, G.H. Contemporary organic contamination levels in digested sewage sludge from treatment plants in Korea: (2) Non-alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Environ. Sci. 2005, 14, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.G.; Park, M.E.; Sung, K.Y. Distribution of heavy metals in marine sediments at the ocean waste disposal site in the Yellow Sea, South Korea. Geosci. J. 2009, 13, 15–24. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12303-009-0002-8 (accessed on 3 February 2009). [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Shin, K.H. Alkylphenols in the core sediment of a waste dumpsite in the East Sea (Sea of Japan), Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1566–1571. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X09003129 (accessed on 1 July 2009). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.S.; Song, K.H.; Choi, K.Y.; Kim, Y.I.; Kim, H.E.; Jung, J.M.; Kim, C.J. Variations in the concentrations of heavy metals through enforcement of a rest-year system and dredged sediment capping at the Yellow Sea-Byung dumping site, Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 512–520. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X17306148 (accessed on 14 July 2017). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.M.; Choi, K.Y.; Chung, C.S.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, S.H. Fractionation and risk assessment of metals in sediments of an ocean dumping site. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 227–235. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X19301407 (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Botton, M.L. Effects of sewage sludge on the benthic invertebrate community of the inshore New York Bight. Estuar. Coast. Mar. Sci. 1979, 8, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOF (Ministry of Ocean and Fisheries). Development of the Best Practical Technology and Management Options for the National Disposal of Wastes at Sea; Final report (16th); Ministry of Ocean and Fisheries: Sejong, Korea, 2019.

- In Public Sewage Statistics, Ministry of Environment. 2013. Available online: www.me.go.kr/home/web/policy_data/read.do?menuId=10264&seq=6564 (accessed on 1 December 2014).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).