Abstract

Tourism has played a fundamental role in shaping the image of destination countries. This study aimed to examine changes in international tourists’ enhanced and complex destination-country images (DCIs) by comparing pre- and post-trip perceptions. A total of 268 and 275 valid questionnaires from pre- and post-trip Chinese outbound tourists to South Korea, respectively, were collected. The results indicated that tourists’ DCIs were dynamic and could be effectively promoted through their actual tourism experiences. Overall, when considering enhanced DCI perception, compared with pre-trip tourists, post-trip tourists possessed a positive complex DCI perception. Tourism could provide an important channel for promoting a destination country’s image to the world.

1. Introduction

With the globalization of the world economy, countries are facing heightened competition for investments, immigrants, tourists, etc. A favorable country image has become the most important form of soft power, and the impetus that promotes a country’s international competitiveness against the background of fast development under globalization [1]. In particular, the tourism industry has become an increasingly essential ingredient in the global economy. Given the intensive competition in the tourism market, the overall image of a country plays an important role in attracting international tourists [2,3]. However, most studies on tourism destination image have focused on the image of a tourist destination, while ignoring the destination in a country image context [4,5,6]. Country image includes consumers’ perceptions of country stereotypes, reflected in a country’s politics, economy, cultural heritage, technological resources at the macro level, and specific product categories at the micro-level [7,8]. Both the macro and micro characteristics may come into play in the choice of tourism destination country [9,10]. Therefore, tourism managers and researchers should pay considerable attention to the role that destination-country image plays in attracting international tourists.

According to Zhang et al. [10], destination-country image (DCI) is defined as international tourists’ mental representations of their overall cognition and affection regarding a given country for a tourist destination, and it is composed of the macro DCI and micro DCI. The macro DCI refers to tourists’ perceptions and impressions of politics, the economy, technology, the environment, people, and other factors of a destination country. The micro DCI refers to the core tourism product image related to tourist attractions and tourism facilities. Compared with the macro DCI, the micro DCI emphasizes the core tourism product aspects more.

However, the question of whether tourists’ perception of a destination image is able to be changed remains controversial. Some scholars believe that tourism destination image is dynamic [11], while others believe this dynamism only refers to changes in dimensions of the destination image, and the overall image is quite stable [12]. At present, researchers are mainly focused on comparative studies of pre- and post-trip tourist destination image changes. Results show that post-trip tourists’ destination image is more positive than that of pre-trip tourists. However, Hughes and Allen [13] disclosed that there is no difference in country image between visitors and non-visitors when comparing these two groups’ overall country image. Therefore, whether international tourists’ actual tourism experience enhances destination-country image remains an important question for tourism destination marketers and researchers to answer. If well-understood, it could provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for a destination-country to shape its country image and develop an international tourism market.

In the international tourism context, tourists’ travel experiences are composed of the different products of a destination country that can co-meet their needs. Tourists’ actual travel experiences in a destination country will promote adjustment and reshaping of their DCI [14,15]. Hence, Smith et al. [15] suggested that tourists’ actual travel experience-related feelings will contribute to the tourist’s DCI. To extend the findings of prior studies, this study focuses on the analysis of DCI perception changes between pre-trip and post-trip international tourists. Tourists’ DCI perceptions vary throughout the different stages of their travel. Pre-trip tourists’ DCIs may be shaped by various types of indirect information. In contrast, those who are traveling acquire direct information on the destination country, which helps shape a richer and more factual DCI [16]. The present study answers the following questions: (1) Does the DCI change, and how has the DCI changed?, (2) does tourism experience enhance or weaken the DCI? To answer the above questions, this article selects South Korea (hereafter Korea) as a destination country to investigate, in pre-trip and post-trip Chinese outbound tourists, DCI perception changes in the context of international tourism and seeks to provide a thorough understanding of the tourism experience effect on the DCI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Country Image and DCI

Country image is a mainstream research area in the international trading, marketing, and tourism fields. Diverse disciplines have defined the concept of country image differently, to accommodate varied research contexts. From the perspective of consumers, a widely held view is that the concept of a country image includes a country-of-origin effect (specific product country image), product-country image (aggregate product country image), and country stereotype (overall country image) [17,18]. “Specific product country image” refers to consumers’ overall perceptions of a particular country’s products [19,20], “aggregate product country image” focuses on the image of countries and their products [21], and “overall country image” represents consumers’ overall perception of a country. When consumers purchase products from a specific country, the country image (positive or negative) will be linked with the country’s products (positive or negative evaluation), resulting in a country-of-origin effect [18,22]. Therefore, international trading and marketing scholars have connected the specific country with the evaluation of specific products to study country image and have deconstructed the country image into macro and micro components (see Table 1) [8,23].

Table 1.

Macro and micro country image (CI) dimensions [18,24,25].

From the perspective of tourism consumers, a tourism destination is a kind of experience product, and the tourism destination image corresponds to the product image in the international trading and marketing field [26,27]. However, the destination image at the country level is not exactly the same as the product image. It includes not only dimensions that relate to tourism activities, such as tourism attractions, transportation, accommodation, food, and entertainment, but also the dimensions of politics, the economy, the environment, and people, which overlap with the content of the country image concept in the international trading and marketing field [9,10]. To further illuminate the country image concept and measurement in the tourism context, this study adopted the concept of the DCI [10]. Zhang et al. integrated the abovementioned overlapping contents into the macro DCI and defined it as international tourists’ perception of macro DCI factors, including the political, economic, technical, cultural, character of the people, and competence dimensions. The micro DCI is the core tourism product image that meets international tourists’ needs, and includes aspects such as tourism attractions, service infrastructure, and tourism activities in the destination country.

However, environmental management and affective DCI dimensions were not included in the DCI in the study by Zhang et al. [10]. Environmental management is an important indicator to measure a country's development. It is closely related to tourists’ actual tourism experiences in a destination country [24]. Further, international tourists prefer to choose countries with relatively good environmental quality as tourism destinations. Thus, the environmental management dimension was included in the DCI in the present study. Based on Attitude Theory [28], the country image can be divided into cognitive and affective country images. The cognitive country image is the consumers’ beliefs about a particular country. The affective country image is the emotional response of the consumer to the country [9,25,29]. According to Roth and Diamantopoulos, most of the scales measuring country image studies lacking an affective dimension. Likewise, the DCI can be divided into the cognitive and affective DCIs in the tourism context [30,31,32,33]. In the present study, the macro DCI was further disaggregated into the macro cognitive DCI and macro affective DCI aspects, and the micro DCI into the micro cognitive DCI and micro affective DCI. The macro cognitive DCI, as defined here, refers to tourists’ overall beliefs about a particular country. The micro cognitive DCI refers to tourists’ beliefs about the core tourism product of a destination country. The macro affective DCI refers to tourists’ affective evaluations of a particular country. The micro affective DCI refers to tourists’ affective evaluations of a destination country [10,25].

2.2. Factors That Affect the DCI

The DCI is mainly influenced by stimuli and personal response factors (e.g., mega events, tourism experiences). Stimuli factors are the characteristics of the object being perceived, and personal response factors are internal [34].

Mega-events are important external factors that influence the DCI. However, most studies have emphasized the influence of major events on changes in the macro DCI, and there has been little exploration of micro DCI perception changes. It is widely accepted that events help to enhance the DCI [35]. A great number of scholars have conducted empirical studies of pre- and post-event destination image changes. For instance, Zeng et al. [36] examined the Beijing Olympic Games as an example and concluded that it served to promote a better understanding of China in the world’s media and for the global public. However, after the Olympic Games, China’s international image did not significantly improve. Ritchie and Smith [37] suggested that the success of the Winter Olympic Games in 1988 in Calgary caused the city to be mentioned much more frequently when compared with other cities in Canada. The city image was also tangibly improved, which enabled Calgary to have a stronger competitive advantage in the long term from the perspective of tourism.

Individual behaviors like information searching, tourism activity participation, and tourism experience are important internal factors that influence the DCI. The evolution process of a tourist’s trip is a dynamic changing process of the DCI [38]. During the pre-trip, a tourist’s DCI perception changes with information acquisition, information source, and subjective judgment of the available information. During the post-trip, a tourist’s DCI perception changes again due to their perception of tourism destination products [39]. For instance, Kim and Morrison [11] used a before-after design and investigated international tourists’ country image changes of Korea after event participation. They found that personal experience affects country image perception, in that the country image perception of post-event tourists tended to be higher compared with pre-event tourists. Chaudhary [14] investigated tourists from Germany, the U.K., and the Netherlands to examine their pre- and post-trip perception of Indian tourism, and came to a conclusion that, except for a slight promotion of the image perception of art, cultural heritage, safety, and guide service, the post-trip Indian image among tourists tends to be more negative than the pre-trip image.

2.3. Enhanced DCI and Complex DCI

The dynamic nature of the destination image has been given various names [16,40]. Tourism destination images could be divided into organic, induced, and complex images [12]. The organic image refers to an image that is mainly formed based on non-commercial marketing information. The induced image is mainly formed by commercial marketing information, and the complex image is a more realistic image formed by a combination of actual tourism experience and former knowledge. With the boom of information, diversified information sources such as social media and online social networks have begun to greatly influence destination images. The marketing strategies and modes of tourism information dissemination for tourism destinations are becoming increasingly flexible. The coexistence of commercial and non-commercial information sources enables tourists to acquire tourism information that is both commercial and non-commercial, blurring the distinction between organic and induced images. In this regard, Li et al. proposed that a destination image shaped with information that is passively available to potential tourists is called the baseline image, whereas the image shaped after tourists’ intentional and active search for destination information is called the enhanced image. They adopted mixed-methods experiments to analyze the destination image differences between pre- and post-information collection and found that the affective and overall image were both significantly and positively changed after online information search. However, the cognitive image basically remained the same [41]. The analysis of the evolution of baseline and enhanced images in Li et al. mainly focused on the perspective of tourism information searches and discussed image perception changes caused by potential tourists’ active information searching behavior. However, tourists’ actual tourism experiences in a destination promote adjustment and reshaping of the destination image, thereby forming a more complex image.

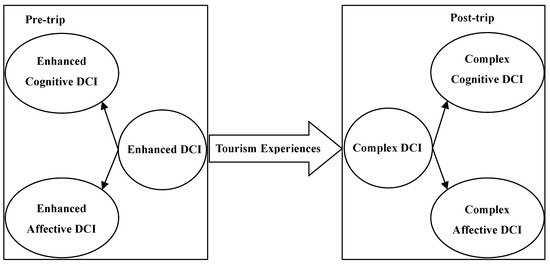

From the perspective of the dynamic development of DCIs, the present study divided the DCI into the baseline DIC, referring to the DCI before international tourists’ decision making, the enhanced DCI, referring to the DCI shaped by international tourists’ positive information search after tourism decision making but before the actual trip, and the complex DCI, referring to the DCI shaped after tourists’ personal travel experiences in the destination country. As Figure 1 shows, the actual travel experiences of international tourists caused the pre-trip enhanced DCI to evolve into the post-trip complex DCI. The objective of this research was to investigate the perception changes in the enhanced DCI and complex DCI measurement items and related factors between pre-trip and post-trip international tourists.

Figure 1.

Perception changes of the DCI between pre-trip and post-trip tourists.

3. Research Method and Data Collection

3.1. Survey Questionnaire Development

In the international tourism context, the DCI contains both the macro and micro DCI. Based on previous studies, the measurement dimensions of the macro cognitive DCI were divided into country’s character, country’s competence, people’s character, people’s competence [9,18,23], environmental management, and national relationship [24,25]. In the present work, the measurement items of the macro affective DCI included “I like Korea” and “I enjoy being with Koreans” [9,21]. Based on the scale of the tourism destination images of Beerli and Martín [32] and Lee et al. [42], the micro DCI in this study referred to the image related to tourism core products. The micro cognitive DCI was divided into tourism attractions, destination’s environment, and service infrastructure. The micro affective DCI contained “Travel in Korea makes me very happy,” “Travel in Korea makes me relaxed,” and “Travel in Korea makes me excited.” A five-point Likert-type scale was adopted to evaluate the measurement items (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree).

3.2. Data Collection

Korea is one of the top foreign tourism destination countries for Chinese tourists. This research used Korea as a tourism destination country and Chinese outbound tourists as research subjects. The outbound Korea trip of Chinese tourists was divided into the pre-trip and post-trip stages. Considering the comparatively smaller geographical area, Chinese tourists prefer team tours, and often have fixed tour routes, including several major tourism cities like Seoul, Inchon, Gimpo, Busan, and Jeju. Usually, Jeju is the last leg of the trip. In this regard, the research samples were mainly Chinese tourists who had traveled to several cities in Korea. Data collection in the pre-trip stage involved a pre-trip tourists’ questionnaire survey, which was carried out in the international departure hall of Hefei Xinqiao International Airport, Nanjing Lukou International Airport, and Shanghai Pudong International Airport in January and March 2015. Based on flights to Korea, this study selected Chinese tourists as questionnaire respondents using convenience sampling. Before distributing the pre-trip questionnaire, the investigator briefly demonstrated the aim of the investigation and asked the respondent, “Is this the first time you have traveled to Korea?” The questionnaire was only released to those who answered “Yes”, which helped to correctly measure tourists’ enhanced DCI. The questionnaires were distributed and retrieved on the spot, as soon as the respondents were finished. A total of 350 questionnaires were distributed, of which 268 were valid, for a valid questionnaire response rate of 77%. Data collection in the post-trip stage involved a post-trip tourists’ questionnaire survey, which was carried out in the departure hall of Jeju International Airport in March 2015. Jeju was selected because it is the main tourism destination and departure port in Korea for Chinese tourists. Chinese tourists were again selected as questionnaire respondents using convenience sampling. Of the 350 questionnaires distributed, 275 were deemed valid (valid questionnaire response rate of 79%). The total number of samples (pre-trip and post-trip tourists) was 543.

3.3. Comparison of Demographic Characteristics between Pre-trip and Post-trip Tourists

In order to ensure any comparative analysis of the perception difference in DCI between pre- and post-trip tourist samples would be valid, this paper applied the chi-square test to analyze the difference in the variable structure of demographic characteristics between the pre- and post-trip tourist samples. The demographic characteristics of the two research samples (pre-trip and post-trip tourists) are presented in Table 2. The chi-squares test for pre-trip and post-trip tourists’ demographic variables, given in Table 3, revealed no significant differences in the sex (χ2 = 4.385, p = 0.112), age (χ2 = 6.845, p = 0.114), occupation (χ2 = 17.769, p = 0.123), monthly income (χ2 = 8.301, p = 0.217), marital status (χ2 = 4.916, p = 0.296), or completed education (χ2 = 0.304, p = 0.959) between the two samples. The majority of both samples were people aged between 25 and 44 years with a bachelor’s degree, whose monthly income ranged between CNY 4000 and 6000. Most of them were female and company employees. The distribution of marital status was relatively even. The chi-squared test results showed that the demographic characteristics of the pre-trip Chinese tourists bore strong similarities to those of the post-trip Chinese tourists. Therefore, it is reasonable to make comparisons between the two samples.

Table 2.

Profile of the respondents.

Table 3.

Chi-square test for pre-trip and post-trip tourists’ demographic variables.

4. Results

This study mainly used SPSS software to analyze the collected data, with analysis methods, including the independent sample t-test and exploratory factor analysis. This paper adopted the independent sample t-test to analyze the differences in the mean values of DCI items between the pre- and post-trip tourist samples. Next, exploratory factor analysis was applied to figure out the DCI factors. Finally, this paper adopted the independent sample t-test to analyze the differences in the mean value of DCI factors between the pre- and post-trip tourist samples.

4.1. Change in the Mean Values of Macro DCI Items

The changes in the macro DCI items (see Table 4) showed that the mean value of each item was above 3.40. Considerable differences between the pre- and post-trip tourists were observed. Compared with the pre-trip tourists, post-trip tourists’ perceptions of all measurement items were significantly improved, which demonstrated that Chinese tourists’ actual tourism experiences in Korea were better than their pre-trip expectations. The post-trip tourists offered a comparatively positive evaluation of Korea’s macro DCI. On the measurement item “Korea is a country that respects the environment,” especially, both the pre- and post-trip tourists gave the highest score. Meanwhile, both tourist samples gave the lowest score on the item “I enjoy being with Koreans.”

Table 4.

Change in the mean value of macro destination-country image items.

According to the perception changes in the macro DCI items, the change degree in the mean value of the item “Korea has made positive efforts to protect the environment” was the highest, increasing by 0.58 from the pre-trip’s 3.57 to the post-trip’s 4.15. In addition, compared with pre-trip tourists, the mean value of post-trip tourists’ perceptions of the items “Korea is a country that respects the environment” and “Korea has strict controls on environmental pollution” increased by more than 0.50. It can be concluded that the post-trip Chinese tourists’ perceptions of Korea’s environmental problems and management were significantly better compared with those of pre-trip tourists, and they positively perceived the achievements that Korea has made in this respect. However, the change degree in the mean value of the item “Bilateral relations between China and Korea are friendly” was the lowest, increasing by only by 0.15 from the pre-trip’s 3.69 to the post-trip’s 3.84.

4.2. Change in the Mean Values of Micro DCI Items

The perception differences in the micro DCI between pre- and post-trip tourists were determined with the independent samples t-test (see Table 5). Significant differences were observed in the perception of most items, namely: “Personal security is not a problem in Korea,” “The climate is good in Korea,” “Hygiene and cleanliness standards in Korea are good,” “Korea has suitable accommodation,” “The natural scenery in Korea is beautiful,” “The environment in Korea is not polluted and destroyed,” “Travel in Korea is good value for money,” “Travel in Korea makes me relaxed,” and “Travel in Korea makes me excited.” No significant differences in perception were observed for the following six items: “It is easy access tourism information about Korea,” “Korea is a good place for shopping,” “Korea has good recreational facilities,” “Korea has interesting historical and cultural attractions,” “Korea is an exotic destination,” and “Travel in Korea makes me very happy.” According to the changes in micro DCI items, there were improvements but also reductions in measurement items between the pre- and post-trip tourists. Post-trip tourists’ evaluations of most items improved compared with pre-trip tourists’. However, post-trip tourists’ evaluation of “Korea has good recreational facilities,” “Korea has interesting historical and cultural attractions,” and “Travel in Korea makes me excited” were lower compared with pre-trip tourists. It can be concluded from the mean values of the micro DCI items that “Korea is a good place for shopping” scored the highest (mean = 3.90) and “Korea has interesting historical and cultural attractions” scored the lowest (mean = 3.49) among pre-trip tourists, whereas “Hygiene and cleanliness standards in Korea are good” scored the highest (mean = 4.23) and “Travel in Korea makes me excited” scored the lowest (mean = 3.28) among post-trip tourists. As for the change degree in the micro DCI items, the mean value of “Personal security is not a problem in Korea” was the highest, increasing by 0.54 from the pre-trip’s 3.63 to the post-trip’s 4.17. The change degree in the mean value of “Travel in Korea makes me very happy” was the lowest, increasing by only 0.01 from the pre-trip’s 3.79 to the post-trip’s 3.80.

Table 5.

Change in the means of micro destination-country image items.

4.3. Change in the Mean Values of DCI Factors

This study combined the DCI measurement items in both the pre-trip and post-trip tourists’ sample data (total number of samples = 543), and then applied exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to determine the DCI factors. The change characteristics of the DCI at the factor level were determined by comparing the mean values of the factors.

SPSS Statistics 23.0 was used to conduct EFA of the macro cognitive DCI, macro affective DCI, micro cognitive DCI, and micro affective DCI. The factors and items in the EFA of the macro cognitive DCI measurement scale showed that KMO was 0.897, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p = 0.000), and the hypothesis of the independent variable was invalid. These outcomes met the basic requirement of factor analysis, and as such, the adoption of factor analysis was applicable. The study applied varimax rotation to run EFA and regarded Eigenvalues > 1, factor loading > 0.50, and communality > 0.50 as prerequisites. The items that did not meet the requirements were deleted. EFA was again run with the remaining factors and finally identified four factors: “Country’s competence” (Alpha = 0.80), “National relationship” (Alpha = 0.71), “People’s character” (Alpha = 0.89), and “Environmental management” (Alpha = 0.84), the total variance was 71.29%.

The EFA of the micro cognitive DCI measurement scale showed a KMO of 0.855 and significant results for Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p = 0.000), indicating that the micro cognitive DCI measurement items had multi-related dimensions and that the adoption of EFA was applicable. After the EFA, three factors were obtained: “Destination’s environment” (Alpha = 0.65), “Service infrastructure” (Alpha = 0.71), and “Tourism attraction” (Alpha = 0.77), the total variance was 59.79%.

Using an independent samples t-test for the DCI factors (see Table 6), the study found significant differences in country’s competence, national relationship, people’s character, environmental management, macro affective DCI, and destination’s environment between the pre-trip and post-trip tourists. However, no significant differences were seen in the service infrastructure, tourism attractions, and micro affective DCI between the samples.

Table 6.

Change in the means of destination-country image factors.

According to the changes in the mean value of the DCI factors, the post-tourists’ evaluations of Korea’s DCI were comparatively positive (the mean value of all factors was above 0.35). Except for the decline in the micro affective DCI perception, post-trip tourists’ perceptions of the other DCI factors all improved compared with those of the pre-trip tourists. The comparison of the mean values of the DCI factors showed that the macro affective DCI scored the lowest, both among pre-trip and post-trip tourists. Service infrastructure ranked highest (mean = 3.81) in the pre-trip tourists’ evaluations, whereas environmental management ranked the highest (mean = 4.30) in the post-trip tourists’ evaluations. As for the change degree in the mean values of the DCI factors, the mean value of “Environmental management” was the highest, increasing by 0.54 from the pre-trip’s 3.76 to the post-trip’s 4.30. The change degree in the mean values of the “Micro affective DCI” was the lowest, decreasing by 0.04 from the pre-trip’s 3.71 to the post-trip’s 3.67.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

This study examined the perception changes in enhanced DCI and complex DCI items and factors in the international tourism context, taking Korea as the tourism destination and pre-trip and post-trip Chinese mainland tourists as the research subjects. Regarding Korea’s DCI measurement items between pre-trip and post-trip Chinese tourists, the post-trip tourists’ perceptions of macro DCI measurement items were significantly higher compared with those of pre-trip tourists. This was also the case for most of the micro DCI measurement items. Moreover, perceptions of country’s competence, national relationship, people’s character, environmental management, destination’s environment, and macro affective DCI were significantly changed. Post-trip tourists’ perceptions of country’s competence, people’s character, national relationship, environmental management, destination’s environment, service infrastructure, tourism attraction, and macro affective DCI were higher compared with pre-trip tourists, indicating that post-trip Chinese tourists’ actual experiences met or exceeded their pre-trip expectations. However, post-trip tourists’ perceptions of micro affective DCI factors were comparatively lower compared with those of pre-trip tourists, which could be attributed to tourists’ pre-trip excitement and happiness turning into post-trip relaxation as they returned to China.

The results of this research indicate that, compared with pre-trip tourists in terms of enhanced DCI perception, post-trip tourists possessed a positive complex DCI perception. However, Chaudhary [14] concluded that tourists’ post-trip Indian images were more negative than at pre-trip. Therefore, this is quite a different finding from the results of the present study. The possible reasons for the different results are that Chaudhary collected both pre- and post-trip image perceptions on India at the post-trip stage. As re-evaluation is often distorted by events following the trip, this approach may have yielded inaccurate answers regarding the tourists’ pre-trip images.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The findings suggest that international tourists’ actual travel experiences promote their perceptions of enhanced DCI, evolving into perceptions of complex DCI, as well as improving their impression of the destination country. The results highlight the importance of travel as a way to improve DCIs. International tourists’ travel experiences in the tourism consumption process and non-resident consumption space function as possible ways to adjust the DCI. Pre-trip international tourists will actively search for tourism information related to the destination country, enhancing their cognitive and affective DCIs, and then shaping their enhanced DCI. If post-tourists’ actual perceptions meet or exceed their expectations, they will have a comparatively happy tourism experience, which further helps shape a positive complex DCI. Otherwise, a negative complex DCI will be shaped. However, international tourists are more likely to form a positive complex DCI after traveling to their destination country. This study also supplemented understanding of the cognitive and affective components of the DCI, particularly by including environmental management and the affective DCI in the measurement structure of the DCI. The present study showed that post-trip tourists’ perceptions of environmental management and macro affective DCI factors improved compared with those of pre-trip tourists.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study offers a reference for DCI construction and marketing: Destination countries ought to value the development of inbound tourism, strive to meet the tourism demand for tourism activities of inbound tourists, improve the travel experience quality of inbound tourists to guide inbound tourists to shape a positive DCI, and maximize the role that travel plays in improving DCIs. In this study, post-trip Chinese tourists’ perceptions of service infrastructure, tourism attraction, and the micro affective DCI were generally consistent with those of pre-trip Chinese tourists. However, significant perception changes were noted in people’s character, environmental management, and destination’s environment between the pre-trip and post-trip tourists. The post-trip tourists’ evaluations of environmental management, the destination’s environment, and people’s character were significantly higher compared with those of pre-trip tourists.

5.4. Limitations and Recommendations for Further Study

The results of this research provide a new perspective on the influence of international tourists’ experiences on DCI change. Nonetheless, this study is not free of limitations. First, this research did not differentiate individual tourists and group tourists. There are certain differences in the characteristics of tourism consumption between the two, which might further influence the DCI perception of pre-trip and post-trip tourists. Future research could compare the characteristics of DCI perception changes between individual and group tourists. Second, a follow-up study may be needed to understand the differences between destination-country perceptions of long-haul and short-haul destination countries [5]. China is geographically close to Korea, where a similar culture can be experienced. Whether the actual tourism experience of international tourists enhances the image of a long-haul destination country remains to be answered in tourism research. Thus, investigating post-trip international tourists’ perceptions of a long-haul destination country would provide insightful clues to related research questions. Third, this study takes China as the tourist source country, and Korea as the tourism destination country. Pre- and post-trip tourists’ destination-country image perception might be influenced by geographical and cultural distance. Therefore, much more validation will be required to support these research results. Finally, this study does not take Chinese tourists’ duration of stay in Korea and form of tourism organization into consideration, which might influence tourists’ complex DCI perceptions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, H.Z. and P.Y.; investigation, software, and writing, P.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contribute equally to the work.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41371161).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. The relevance of visitors’ nation brand embeddedness and personality congruence for nation brand identification, visit intentions and advocacy. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Correia, M.B.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. Instagram as a co-creation space for tourist destination image-building: Algarve and Costa del Sol case studies. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Cai, L.A. Dimensionality and associations of country and destination images and visitor intention. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2016, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.Y.; Chen, C.C. The impact of country and destination images on destination loyalty: A construal-level-theory perspective. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.; Day, J.; Sydnor, S.; Lehto, X.; Jaffé, W. Integrating country and brand images: Using the product-country image framework to understand travelers’ loyalty towards responsible tourism operators. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P. Country equity: Conceptualization and empirical evidence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, J.; Heslop, L.; O’Reilly, N.; Luk, P. Destination in a country image context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Leung, H.H.; Cai, L.A. The influence of destination-country image on prospective tourists’ visit intention: Testing three competing models. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Morrsion, A.M. Change of images of South Korea among foreign tourists after the 2002 FIFA World Cup. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.L.; Allen, D. Visitor and non-visitor images of Central and Eastern Europe: A qualitative analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M. India’s image as a tourist destination—A perspective of foreign tourists. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.W.; Li, X.R.; Pan, B.; Witte, M.; Doherty, S.T. Tracking destination image across the trip experience with smartphone technology. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Pan, S.L.; Setiono, R. Product-, corporate-, and country-image dimensions and purchase behavior: A multicountry analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.P.; Diamantopoulos, A. Advancing the country image construct. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.S.; Romeo, J.B. Matching product catgeory and country image perceptions: A framework for managing country-of-origin effects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992, 23, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, A. A comparison of Japanese and US attitudes toward foreign products. J Mark. 1970, 34, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, S.C.; Alvarez, M.D. Country versus destination image in a developing country. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P.W.; Steenkamp, J.B.E. A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P.G.; Cooksey, R.W. Country image and consumer-based brand equity: Relationships and implications for international marketing. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Allred, A.T.; Chakraborty, G. A multidimensional scale for measuring country image. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2008, 21, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Li, D.; Barnes, B.R.; Ahn, J. Country image, product image and consumer purchase intention: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, L.; Kleppe, I.A. Country and destination image–different or similar image concepts? Serv. Ind. J. 2005, 25, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Mills, J.E. Destination image: A meta-analysis of 2000–2007 research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 575–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Allred, A.; Chakraborty, G.; Miller, S.J. Measuring images of developing countries: A scale development study. J. Euromark. 2000, 8, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. TravelTour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D. Tourists’ characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: A quantitative analysis—A case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y.; Huang, J. A missing link in understanding revisit intention—The role of motivation and image. J. TravelTour. Mark. 2010, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. Branding national images: The 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, 2010 Shanghai World Expo, and 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Go, F.; Kolmer, C. The impact of international TV media coverage of the Beijing Olympics 2008 on China’s media image formation: A media content analysis perspective. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2011, 12, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Smith, B.H. The impact of a mega-event on host region awareness: A longitudinal study. J. TravelRes. 1991, 30, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary K, W. US international pleasure travelers’ images of four Mediterranean destinations: A comparison of visitors and nonvisitors. J. TravelRes. 1999, 38, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, M.; Morgan N, J. Reconstruing place image: A case study of its role in destination market research. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J. Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. J. TravelRes. 2014, 53, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pan, B.; Zhang, L.; Smith, W.W. The effect of online information search on image development: Insights from a mixed-methods study. J. TravelRes. 2009, 48, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, B.K. ‘Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 world cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).