The Mediating Effect of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: Middle Eastern Example/Jordan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Statement of the Problem

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Leadership and Leadership Styles

1.2.2. Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

1.2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

1.3. Development of the Hypotheses

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Tools

2.2. Particiants and Data Gathering

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis: First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

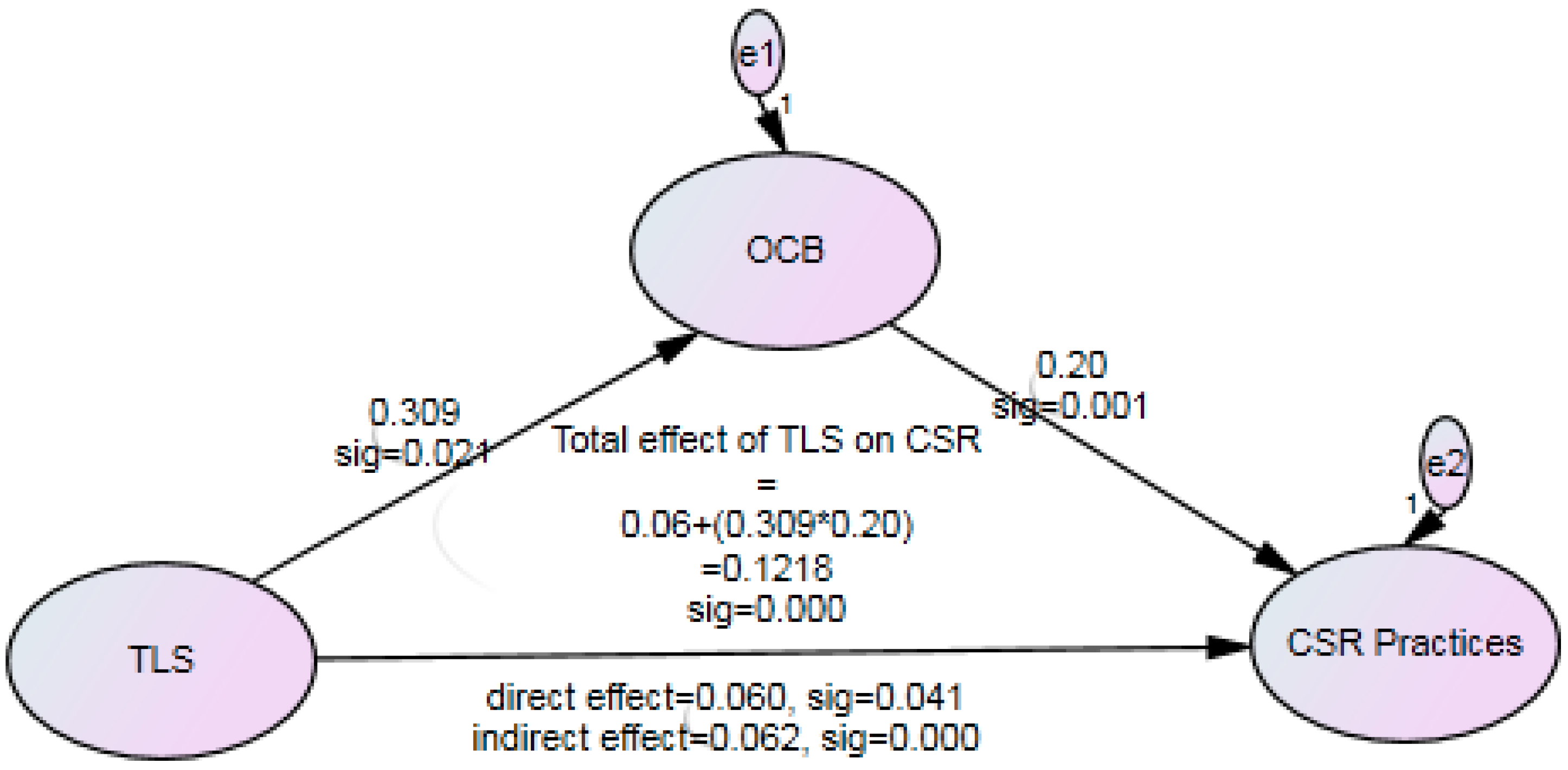

3.3. Effects of TLS, OCB, and CSR Interaction

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Implications

4.2. Contributions

4.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. (TLS) Items

- 1.

- Idealized InfluenceII1 (Instills pride in me for being associated with him/her.)II2 (Goes beyond self-interest for the good of the group.)II3 (Acts in a way that builds my respect.)II4 (Displays a sense of power and confidence.)

- 2.

- Idealized BehaviorIB1 (Talks about their most important values and beliefs.)IB2 (Specifies the importance of having a strong sense of purpose.)IB3 (Considers the moral and ethical consequences of decisions.)IB4 (Emphasizes the importance of having a collective sense of mission.)

- 3.

- Inspirational MotivationIM1 (Talks optimistically about the future.)IM2 (Talks enthusiastically about what needs to be accomplished.)IM3 (Articulates a compelling vision of the future.)IM4 (Expresses confidence that goals will be achieved.)

- 4.

- Intellectual StimulationIS1 (Re-examines critical assumptions to question whether they are appropriate.)IS2 (Seeks differing perspectives when solving problems.)IS3 (Gets me to look at problems from many different angles.)IS4 (Suggests new ways of looking at how to complete assignment.)

- 5.

- Individual ConsiderationIC1 (Spends time teaching and coaching.)IC2 (Treats me as an individual rather than just as a member of the group.)IC3 (Considers me as having different needs, abilities, and aspirations from others.)IC4 (Helps me to develop my strengths.)

Appendix B. (OCB) Items

- 1.

- ConscientiousnessCons 1 (I believe in giving an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay.)Cons 2 (My attendance at work is above the norm.)Cons 3 (I don’t take extra breaks.)Cons 4 (Obeys organization rules and regulations even when no one watching.)Cons 5 (I am one of most conscientious employees.)

- 2.

- Sportsmanship (reverse questions)Sport 1 (I am the classic “squeaky wheel” who always needs greasing.)Sport 2 (I consume a lot of time complaining about trivial matters.)Sport 3 (I tend to make “mountains out of molehills”.)Sport 4 (I always focus on what’s wrong, rather than the positive side.)Sport 5 (I always find fault with what the organization is doing.)

- 3.

- Civic VirtueCivVir 1 (I keep abreast of changes in the organization.)CivVir 2 (I attend meetings that are not mandatory, but are considered important.)CivVir 3 (I attend functions that are not required, but help the organization image.)CivVir 4 (I read and keep up with organization announcements, memos, and so on.)

- 4.

- CourtesyCour 1 (I try to avoid creating problems for coworkers.)Cour 2 (I consider the impact of my actions on coworkers.)Cour 3 (I don’t abuse the rights of others.)Cour 4 (I take steps to try to prevent problems with other workers.)Cour 5 (I am mindful of how my behavior affects other people’s jobs.)

- 5.

- AltruismAltru 1 (I help others who have heavy workloads.)Altru 2 (I am always ready to lend a helping hand to those around me.)Altru 3 (I help others who have been absent.)Altru 4 (I willingly help others who have work related problems.)Altru 5 (I help orient new people even though it is not required.)

Appendix C. (CSR) Practices Items

References

- Anderson, S.; Cavanagh, J. Top 200: The Rise of Corporate Global Power; Institute of Policy Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbonna, E.; Harris, C. Leadership style, organizational culture and performance: Empirical evidence from UK companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, D. The Link between Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) and Sustainability; Allied Telesis, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.; Dukerich, J.; Harquail, C. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, M.J. Government as a Driver of Corporate Social Responsibility. In Dirk, International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility; No. 20-2004 ICCSR Research Paper Series; ICCSR: New Delhi, India, 2004; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, R.N. Self-Organising Leadership: Transparency and Trust. In Management Models for Corporate Social Responsibility; Jonker, J., de Witte, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, M.L. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting through the Lens of ISO 26000: A Case of Malawian Quoted Companies. Int. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shephard, K.; Guiney, B. Researching the professional-development needs of community-engaged scholars in a New Zealand university. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nejati, M.; Shafaei, A.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Daraei, M. Corporate social responsibility and universities: A study of top 10 world universities’ websites. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Buffington, J.; Hart, S.; Milstein, M. Tandus 2010; Race to Sustainability; Center for Sustainable Enterprise, University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Haden, S.; Oyler, P.H.J. Historical, practical and theoretical perspectives on green management: An exploratory analysis. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C. Greening of business schools: A systemic view. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Abubakar, I. An integrated approach to achieving campus sustainability: Assessment of the current campus environmental management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deegan, C. The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures-A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, F. Dealing with misconceptions on the concept of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2000, 1, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Morrison, E. Psychological contracts and (OCB): The effect of unfulfilled obligations. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohe.org; The Ministry of Higher Education: Amman, Jordan, 2018.

- Allmer, T. Theorising and Analysing Academic Labour. TripleC 2018, 16, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; Avolio, B.J. Developing transformational leadership: 1992 and beyond. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1990, 14, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D.; Boyatzis, R.; Mckee, A. The New Leaders. Transforming the Art of Leadership into the Science of Results; Little, Brown: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yusra, K.; Sana, A. Leadership Styles & Using Appropriate Styles in Different Circumstances. Researchgate 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323797001_Leadership_Styles_Using_Appropriate_Styles_in_Different_Circumstances (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Pillai, R.; Schriesheim, C.; Williams, E. Fairness perceptions and trust as mediators for transformational and transactional leadership: A two-sample study. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 897–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagude, J.; Charles, R.; Anne, N. Influence of Idealized Behaviour On the Implementation of Cdf Construction Projects in Public Secondary Schools in Kisumu County, Kenya. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, I.; Adell, F.L.; Alvarez, O. Relationships between personal values and leadership behaviors in basketball coaches. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, B.; Smith, B.; Slobodnikova, A. Visual Images of People at Work: Influences on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. In Visual Ethics Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations; Schwartz, M., Harris, H., Comer, D., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.V. Do good citizens make good organizational citizens? An empirical examination of the relationship between general citizenship and organizational citizenship behavior in Israel. Adm. Soc. 2000, 32, 596–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igor, K.; Daniel, H.; Mari, B. Predicting organizational citizenship behavior: The role of work-related self. Sage Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; MohdZabid, A. The mediating effect of organizational commitment in the organizational culture, leadership and organizational justice relationship with organizational citizenship behavior: A study of academicians in private higher learning institutions in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ozyilmaz, A.; Erdogan, B.; Karaeminogullari, A. Trust in organization as a moderator of the relationship between self-efficacy and workplace outcomes: A social cognitive theory-based examination. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H. The interactive effect of positive psychological capital and organizational trust on organizational citizenship behavior. Sage Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbode, G.A. Personality Characteristics as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB). Master’s Thesis, Department of Psychology, Unilag, Lagos, Nigeria, 2010. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Okediji, A.A.; Esin, P.; Sanni, K.B.; Umoh, O.O. The influence of personality characteristics and gender on organizational citizenship behavior. Glob. J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 8, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. The roles of tacit knowledge and (OCB) in the relationship between group-based pay and firm performance. J. Technol. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 9, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broucek, W. An examination of organizational citizenship behavior in an academic setting from the perspective of the five factor model. J. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. 2003, 2, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, N.; Ababneh, R.; Kyung Bae, Y. The impact of (TLS) on innovation as perceived by public employees in Jordan. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2012, 22, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareq, G. The impact of (TLS) on organizational performance: Evidence from Jordan. Int. J. Hum. Res. Stud. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akif, L.; Sahar, M. The impact of leadership styles used by the academic staff in the Jordanian public universities on modifying students’ behavior: A field study in the northern region of Jordan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alsheikh, G.; Sobihah, M. Effect of behavioral variables on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), with job satisfaction as moderating among Jordanian five-star hotels: A pilot study. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2019, 35, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, E.; Cohen, A. The role of values and leadership style in developing (OCB) among Arab teachers in Israel. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 308–327. [Google Scholar]

- Oo, E.; Jung, H.; Park, I.-J. Psychological Factors Linking Perceived CSR to OCB: The Role of Organizational Pride, Collectivism, and Person–Organization Fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cingöz, A.; Akdogan, A. A Study on Determining the Relationships among Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Ethical Leadership. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2018, 16, 1940004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; He, W. Corporate social responsibility and employee organizational citizenship behavior: The pivotal roles of ethical leadership and organizational justice. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Corporate Social Responsibility and Collective OCB: A Social Identification Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohammad, H.; Nik, R. The Implementation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Programs and its Impact on Employee Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Int. J. Bus. Commer. 2012, 2, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, M.; Mayer, D.; Leigh, P.T.; Wellman, N. When corporate social responsibility motivates employee citizenship behavior: The sensitizing role of task significance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. Res. Collect. Lee Kong Chian Sch. Bus. 2018, 144, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Farid, T.; Ma, J.; Khattak, A.; Nurunnabi, M. The Impact of Authentic Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behaviours and the Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Banking Sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazutis, D. CEO open executive orientation and positive CSR initiative adoption. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-S.; Thapa, B. Relationship of Ethical Leadership, Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 447. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.; Avolio, B.; Gardner, W.; Wernsing, T.; Peterson, S. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Schaubroeck, J.; Avolio, B.J. Retracted: Psychological Processes Linking Authentic Leadership to Follower Behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira-Lishchinsky, O.; Tsemach, S. Psychological Empowerment as a Mediator Between Teachers’ Perceptions of Authentic Leadership and Their Withdrawal and Citizenship Behaviors. Educ. Adm. Q. 2014, 50, 675–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edú, V.; Moriano, J.; Molero, A.; Topa, C. Authentic leadership and its effect on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviours. Psicothema 2012, 24, 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.; Avolio, B. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Manual and Sampler Set, 3rd ed.; Mind Garden Inc.: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Paine, J.; Bachrach, D. Organizational citizen ship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y.; Singh, S. On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs: Two extensions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1991, 8, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Kenny, D.A. Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aksu-Dunya, B.; Karakaya-Ozyer, K. A review of structural equation modeling applications in Turkish educational science literature, 2010–2015. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2018, 4, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Frequency | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 241 | 61.5 |

| Female | 151 | 38.5 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 40 Years | 200 | 51.0 |

| 40 Years and Older | 192 | 49.0 |

| Level of Education | ||

| High School and Less | 59 | 15.1 |

| Diploma | 53 | 13.5 |

| Bachelor | 109 | 27.8 |

| Master | 71 | 18.1 |

| Doctorate | 100 | 25.5 |

| Type of Work | ||

| Services | 105 | 26.8 |

| Technicians | 62 | 15.8 |

| Academic | 151 | 38.5 |

| Management | 74 | 18.9 |

| Years of Experience | ||

| 1–5 Years | 47 | 12.0 |

| 6–10 Years | 116 | 29.6 |

| 11 Years and More | 229 | 58.4 |

| Income in JD | ||

| 500 and Less | 157 | 40.1 |

| 501–1000 | 128 | 32.7 |

| 1001–1500 | 69 | 17.6 |

| 1501 and More | 38 | 9.7 |

| Type of University | ||

| Public | 188 | 48.0 |

| Private | 204 | 52.0 |

| Items <--- Component Factors | Initial Factor Loadings | Modified First-Order Loadings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDBEH4 | IDBEH | 0.604 | 0.601 |

| IDBEH3 | 0.650 | 0.643 | |

| IDBEH2 | 0.590 | 0.590 | |

| IDBEH1 | −0.098 | Del | |

| INSMOT4 | INSMOT | 0.609 | 0.625 |

| INSMOT3 | 0.474 | Del | |

| INSMOT2 | 0.517 | 0.538 | |

| INSMOT1 | 0.559 | 0.535 | |

| INTSTIM4 | INTSTIM | 0.487 | Del |

| INTSTIM3 | 0.793 | 0.821 | |

| INTSTIM2 | 0.542 | 0.509 | |

| INTSTIM1 | 0.499 | Del | |

| INDCON4 | INDCON | 0.769 | 0.774 |

| INDCON3 | 0.713 | 0.722 | |

| INDCON2 | 0.433 | Del | |

| INDCON1 | 0.423 | Del | |

| IDINF4 | IDINF | 0.619 | 0.617 |

| IDINF3 | 0.783 | 0.783 | |

| IDINF2 | 0.683 | 0.688 | |

| IDINF1 | 0.715 | 0.711 | |

| Cons1 | Cons | 0.136 | Del |

| Cons2 | 0.862 | 0.895 | |

| Cons3 | 0.886 | 0.878 | |

| Cons4 | 0.515 | Del | |

| Cons5 | 0.279 | Del | |

| Sport1 | Sport | 0.412 | Del |

| Sport2 | 0.645 | 0.516 | |

| Sport3 | 0.362 | Del | |

| Sport4 | 0.743 | 0.802 | |

| Sport5 | 0.547 | 0.600 | |

| CivVir1 | CivVir | 0.297 | Del |

| CivVir2 | 0.933 | 0.923 | |

| CivVir3 | 0.953 | 0.965 | |

| CivVir4 | 0.476 | Del | |

| Cour1 | Cour | 0.461 | Del |

| Cour2 | 0.533 | Del | |

| Cour3 | 0.554 | Del | |

| Cour4 | 0.636 | 0.532 | |

| Cour5 | 0.702 | 0.840 | |

| Altru1 | Altru | 0.912 | 0.912 |

| Altru2 | 0.927 | 0.926 | |

| Altru3 | 0.946 | 0.947 | |

| Altru4 | 0.950 | 0.949 | |

| Altru5 | 0.749 | 0.749 | |

| CSR Practice1 | CSR Practices | 0.519 | 0.508 |

| CSR Practice2 | 0.694 | 0.681 | |

| CSR Practice3 | 0.424 | Del | |

| CSR Practice4 | 0.502 | 0.517 | |

| Fit Index | Recommended Values | Acceptable Values | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN (χ2) | |||

| p-value | >0.05 | ≥0.000 | [59] |

| χ2/df | ≤3.00 | ≤5.00 | [60] |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | ≥0.80 | [61] |

| AGFI | ≥0.80 | ≥0.80 | [61] |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | [60] |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | [59] |

| IFI | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | [59,62] |

| RMSEA | 0.05 to 0.08 | ≤0.10 | [62] |

| Component Factors | Constructs | Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDINF | <--- | TLS | 0.572 |

| IDBEH | <--- | TLS | 0.616 |

| INSMOT | <--- | TLS | 0.511 |

| INTSTIM | <--- | TLS | 0.522 |

| INDCON | <--- | TLS | 0.505 |

| Cons | <--- | OCB | 0.594 |

| Sport | <--- | OCB | 0.578 |

| CivVir | <--- | OCB | 0.502 |

| Cour | <--- | OCB | 0.501 |

| Altru | <--- | OCB | 0.608 |

| EFFECT | TLS | OCB |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Total Effects/Sig | ||

| OCB | 0.309 | … |

| CSR Practices | 0.122 | 0.20 |

| Standardized Direct Effects/Sig | ||

| OCB | 0.309 | … |

| CSR Practices | 0.060 | 0.20 |

| Standardized Indirect Effects/Sig | ||

| OCB | … | … |

| CSR Practices | 0.062 | … |

| EFFECT | TLS | OCB |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Total Effects/Sig | ||

| OCB | 0.021 | … |

| CSR Practices | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Standardized Direct Effects/Sig | ||

| OCB | 0.021 | … |

| CSR Practices | 0.041 | 0.001 |

| Standardized Indirect Effects/Sig | ||

| OCB | … | … |

| CSR Practices | 0.000 | … |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshihabat, K.; Atan, T. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: Middle Eastern Example/Jordan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104248

Alshihabat K, Atan T. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: Middle Eastern Example/Jordan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104248

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshihabat, Khaled, and Tarik Atan. 2020. "The Mediating Effect of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: Middle Eastern Example/Jordan" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104248

APA StyleAlshihabat, K., & Atan, T. (2020). The Mediating Effect of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: Middle Eastern Example/Jordan. Sustainability, 12(10), 4248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104248