The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions of Strategic Alignment on Sustainability: An Empirical Investigation of Korean Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

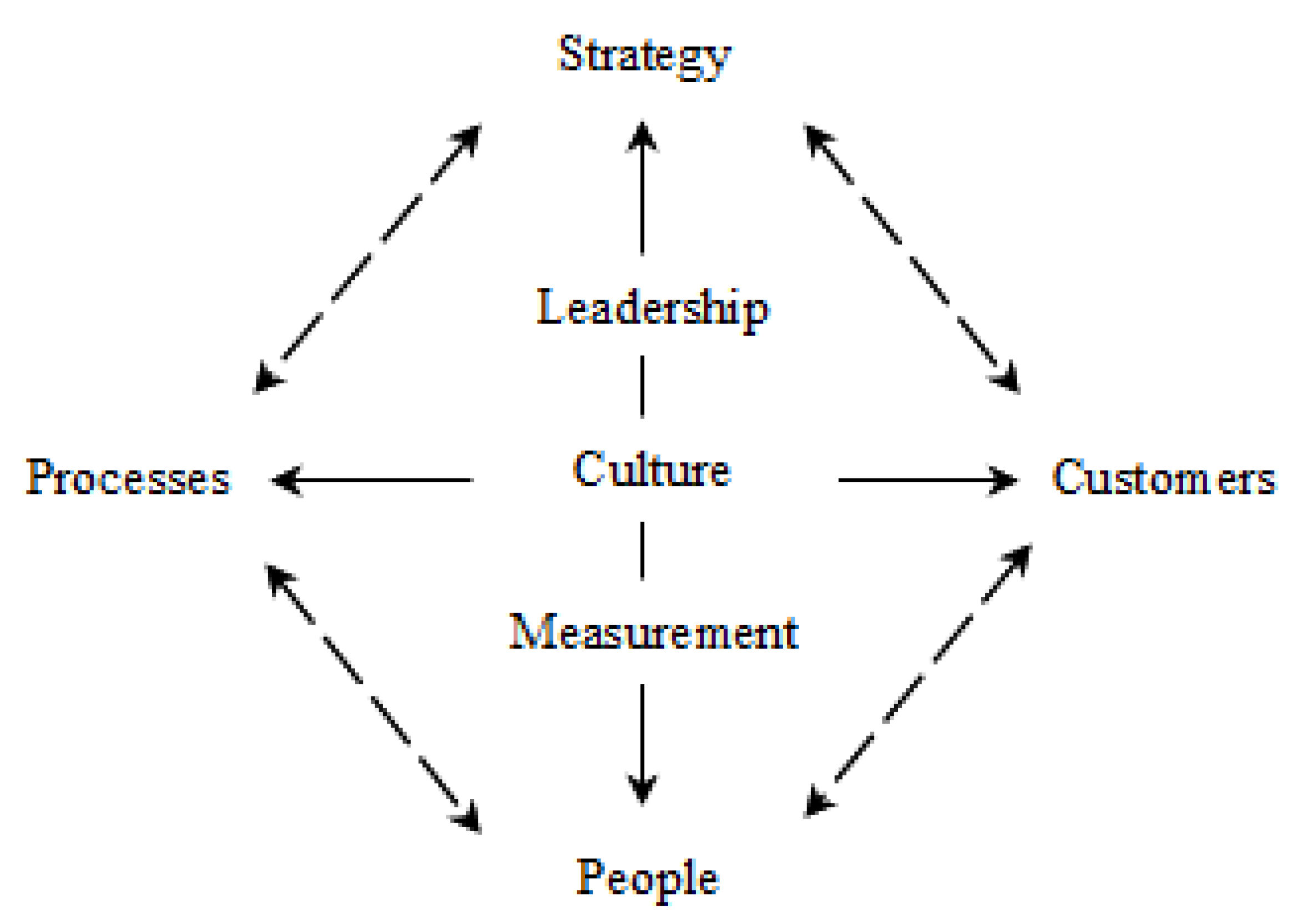

2.1. Strategic Alignment

2.2. Role Clarity: Goal and Process Clarity

2.3. Employee Engagement

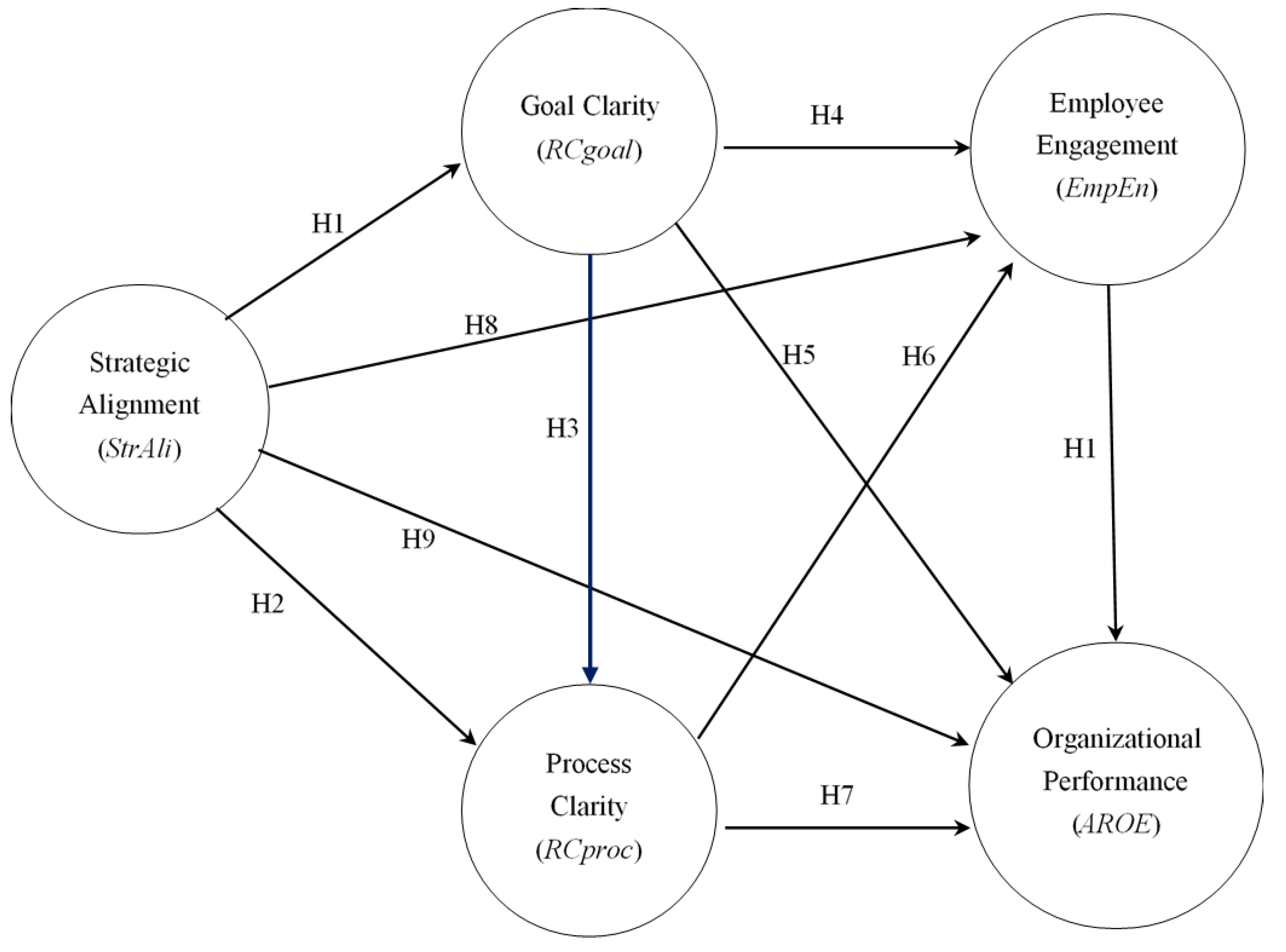

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Relationships between Strategic Alignment and Role Clarity

3.2. Relationships between Role Clarity and Employee Engagement

3.3. Relationships between Strategic Alignment, Employee Engagement, and Organizational Performance

4. Research Method

4.1. Sample and Data

4.2. Variable Description

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Common Method Bias Test

5.3. Data Analysis: Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS)

5.4. Discussion of the Measurement Model

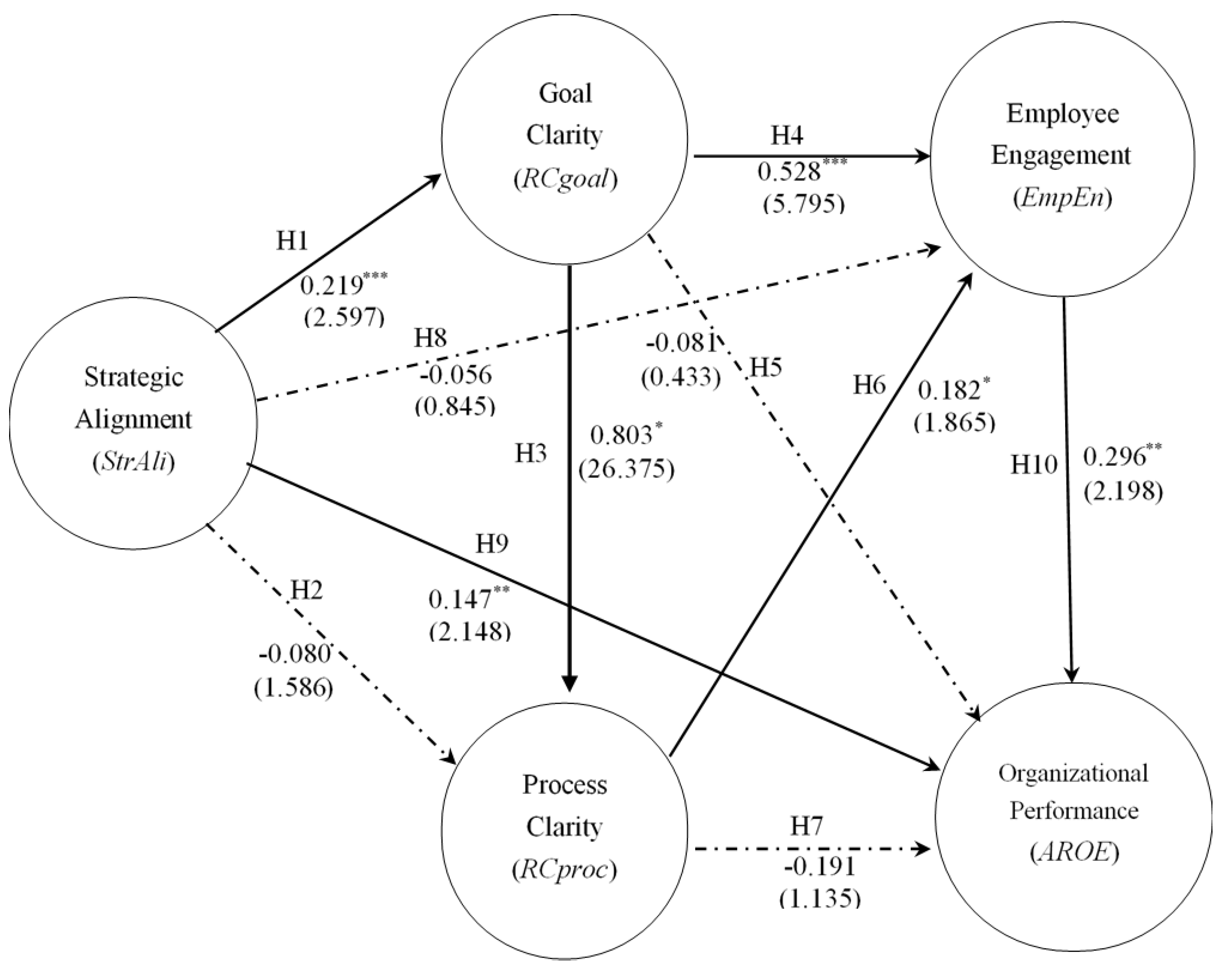

5.5. Discussion of Structural Model: Hypothesis Tests

5.6. Contextual Analysis

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, Y.E.; Sabherwal, R.; Thatcher, J.B. Antecedents and outcomes of strategic IS alignment: An empirical investigation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 53, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Jones, D.; Cao, Q.; Song, J. Conceptualizing the dynamic strategic alignment competency. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, W. Manufacturing: The missing link in corporate strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1969, 47, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, W. Manufacturing in the Corporate Strategy; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Palia, K.A. Industrial firms’ grand strategy and functional importance: Moderating effects of technology and structure. Acad. Manag. J. 1982, 25, 265–298. [Google Scholar]

- Labovitz, H.G.; Rosansky, V.I. The Power of Alignment; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Labovitz, H.G.; Rosansky, V.I. Rapid Realignment: How to Quickly Integrate People, Processes, and Strategy for Unbeatable Performance; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, M.P.; Kathuria, R.; Porth, S.J. Alignment of strategic priorities and performance: An operations perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel, C.M. Alignment: The duality of decision problems. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 1258–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria, R.; Joshi, M.P.; Porth, S.J. Organizational alignment and performance: Past, present and future. Manag. Decis. 2007, 45, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Lee, S.W. Measurement diversity, alignment with firm strategy and organizational performance: A note on the mediating role of organizational learning. Korean Account. J. 2011, 20, 75–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. BSC (Balanced Scorecard) implementation factors and firm performance: The role of communication, strategic alignment, and cooperation. Korean Account. J. 2011, 20, 233–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.G.; Lee, J.H. The effects of strategic alignment on job performance through role stress: Focused on BSC perspective. Korea Int. Account. Rev. 2015, 63, 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, M.; Pouryousefi, S.; Hibbert, S.; Russon, J.A. Sharing vocabularies: Towards horizontal alignment of values-driven business functions. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Hussain, H.I.; Kot, S.; Androniceanu, A.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Role of Social and Technology Challenges in Sustainable Competitive Advantage and Sustainable Business Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholihah, M.; Maezono, T.; Mitake, Y.; Shimomura, Y. PSS strategic alignment: Linking service transition strategy with PSS business model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The contributions of industrial organization to strategic management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 64, 609–620. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Organization and Environment; Reissued as a Harvard Business School Classic, Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ciborra, C.U. De profundis? Deconstructing the concept of strategic alignment. Scand. J. Inf. Syst. 1997, 9, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Smaczny, T. Is an alignment between business and information technology the appropriate paradigm to manage IT in today’s organizations? Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C.; Venkatraman, N. Strategic alignment: A framework for strategic information technology management. In Transforming Organizations: 97–117; Kochan, T., Unseem, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Alagaraja, M.; Shuck, B. Exploring Organizational Alignment-Employee Engagement Linkages and Impact on Individual Performance: A Conceptual Model. Hum. Res. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papke-Shields, K.E.; Malhotra, M.K. Assessing the impact of the manufacturing executive’s role on business performance through strategic alignment. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. What is strategy? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall, R.H.; Langfield-Smith, K. The relationship between strategic priorities, management techniques and management accounting: An empirical investigation using a systems approach. Account. Organ. Soc. 1998, 23, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R.H. Integrative strategic performance measurement systems, strategic alignment of manufacturing, learning and strategic outcomes. Account. Organ. Soc. 2005, 30, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliansyah, Y.; Jermias, J. Strategic performance measurement system, organizational learning and service strategic alignment: Impact on performance. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2018, 34, 564–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. Interaction effect of strategic leadership behaviors and organizational culture on IS-business strategic alignment and enterprise systems assimilation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.; Raymond, L.; Rivard, S. Ideal Patterns of Strategic Alignment and Business Performance. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avison, D.; Jones, J.; Powell, P.; Wilson, D. Using and validating the strategic alignment model. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F. Working with corporate social responsibility in Brazilian companies: The role of managers: Values in the maintenance of CSR cultures. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring Employee Engagement with (Corporate) Social Responsibility: A Social Exchange Perspective on Organisational Participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.W.; Markus, M.L. The Performance Impacts of Quick Response and Strategic Alignment in Specialty Retailing. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, P.P. The alignment paradox. CIO Insight 2003, 1, 75–76. Available online: https://www.cioinsight.com/c/a/Past-News/Paul-Tallon-The-Alignment-Paradox/ (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Shields, M.D.; Deng, F.J.; Kato, Y. The design and effects of control systems: Tests of direct and indirect effect models. Account. Organ. Soc. 2000, 25, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, F. Managerial accounting systems and organizational control: A role perspective. Account. Organ. Soc. 1982, 7, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckett, P.F.; Eggleton, I.R.C. Feedback and management accounting: A review of research into behavioral consequences. Account. Organ. Soc. 1991, 16, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. The effect of comprehensive performance measurement systems on role clarity, psychological empowerment, and managerial performance. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, D.A.; Tushman, M.L. A model for diagnosing organizational behavior: Applying a congruence perspective. Organ. Dyn. 1980, 9, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, D.; Jackson, S.F. Organizational Alignment. 2000. Available online: http://www.ichangeworld.com/docs/icwoa0303.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Weiser, J.R. Organizational alignment: Are we heading in the same direction? Kans. Bank. 2000, 90, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, W.R.; Bingham, J.B.; Colvin, A. Aligning Employees through “Line of Sight”. Bus. Horiz. 2006, 49, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Buller, P.F.; McEvoy, G.M. Strategy, human resource management and performance: Sharpening line of sight. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, M.; Mehra, S. Aligning operations, marketing, and competitive strategies to enhance performance: An empirical test in the retail banking industry. Omega 2006, 34, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Alignment between product innovation and competitive priorities. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2004, 6, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, K. Construct validation of strategic alignment in learning and talent development. Perform. Improv. Q. 2016, 28, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoek, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Occupational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Barbour, J.P. Strategic Alignment with Organizational Priorities and Work Engagement: A Multi-Wave Analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, J.E. Goal and process clarity: Specification of multiple constructs of role ambiguity and a structural equation model of their antecedents and consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liden, R.C. Antecedents of team potency and team effectiveness: An examination of goal and process clarity and servant leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilulio, J.D. Principled agents: The cultural bases of behavior in a federal government bureaucracy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1994, 4, 277–318. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D.; Durham, C.C.; Locke, E.A. The relationship of team goals, incentives, and efficacy to strategic risk, tactical implementation, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, M.; Pavlov, A.; Franco-Santos, M. The contributing effects of performance measurement and human resource management practices. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 1599–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-Unit-Level Relationship between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Wollard, K. Employee Engagement and HRD: A Seminal Review of the Foundations. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2010, 9, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The Psychological Conditions of Meaningfulness, Safety and Availability and the Engagement of the Human Spirit at Work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.; Perryman, S.; Hayday, S. The Drivers of Employee Engagement; Institute for Employment Studies: Brighton, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shon, M.K.; Chang, Y.C. The effect of transformational leadership and transactional leadership on employee job engagement. J. Acad. Ind. Technol. 2013, 29, 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Burney, L.L.; Widener, S.K. Behavioral Work Outcomes of a Strategic Performance Measurement System-Based Incentive Plan. Behav. Res. Account. 2013, 25, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Artz, M.; Wieseke, J. Marketing Performance Measurement Systems: Does Comprehensiveness Really Improve Performance? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, C. The Relationship between Strategic Alignment, Meaningful Work, and Employee Engagement (Dissertation Dissertation); The University of New Mexico: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Social Structural Characteristics of Psychological Empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Kizilos, M.A.; Nason, S.W.A. Dimensional Analysis of the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and Effectiveness, Satisfaction, and Strain. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 679–696. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J.A.; Piderit, S.K. The value of mission statements in public agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1999, 9, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, G. Disentangling the relationship between public service motivation and ethics: An interdisciplinary approach. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2019, 2, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramis, D.J. Work role ambiguity, job satisfaction, and job performance: Meta-analyses and review. Psychol. Rep. 1994, 75, 1411–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubre, T.C.; Collins, J.M. Jackson and Schuler (1985) revisited: A meta-analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conflict and job performance. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W. Aligning Employees with the Organization’s Strategic Objectives: Out of Line of Sight, Out of Mind. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoene, V.; Bruggeman, W. Strategic Alignment and Middle-Level Managers’ Motivation in a Balanced Scorecard Setting. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2006, 26, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.H.; Wheelwright, S.C.; Clark, B.K. Dynamic Manufacturing: Creating the Learning Organization; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, T.C. Organizational alignment as competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. 1992, 13, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Reece, S. The relationship of strategy, fit, productivity, and business performance in a service setting. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, J.M.; Szeto, C. Effective management of information technology: Closing the strategic divide! J. Sci. Ind. Res. 1999, 58, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.; Kay, R.; Avison, D. Strategic alignment: A practitioner’s perspective. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2005, 18, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Woo, C.; Rho, J.J.; Chung, Y.H. Environmental Capabilities of Suppliers for Green Supply Chain Management in Construction Projects: A Case Study in Korea. Sustainability 2016, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.T.; Schwenk, C.R. Top management team strategic consensus, demographic homogeneity, and firm performance: A report of resounding nonfindings. Strateg. Manag. 1996, 17, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Krohmer, H.; Workman, J.P., Jr. Strategic consensus and performance the role of strategy type and market-related dynamism. Strateg. Manag. 1999, 20, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, F.T.; Callarman, T.E.; Fowler, K.L.; McClatchey, C.A. Strategic consensus and manufacturing performance. J. Manag. Issues 2001, 13, 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K.K.; McDermott, C. Strategic Consensus in Operations Strategy. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.; Kwon, H.J. Corporate social responsibility activity combinations for sustainability: A fuzzy set analysis of Korean firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C.D.; Larcker, D.F.; Randall, T. Performance Implications of Strategic Performance Measures in Financial Services Firms. Account. Organ. Soc. 2003, 28, 715–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H. Partial least squares. In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985; Volume 6, pp. 581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Eribaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J. Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Recent Studies. Strateg. Manag. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An Empirical Comparison of the Efficacy of Covariance-Based and Variance-Based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equations with unobservable variables measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Leonardelli, G.J. Calculation for the Sobel Test: An Interactive Calculation Tool for Mediation Tests (Computer Software). Available online: www.quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Ilgen, D.R.; Fisher, C.D.; Taylor, M.S. Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979, 64, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.; Breidahl, E.; Marty, A. Organizational Resources, Organizational Engagement Climate, and Employee Engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Schaufeli, W. Positive Organizational Behavior: Engaged Employees in Flourishing Organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liphadze, S.M.; Vermaak, A.P. Assessment of employees’ perceptions of approaches to sustainable water management by coal and iron ore mining companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.; Raymond, L.; Rivard, S. Fit in strategic information technology management research: An empirical comparison of perspectives. OMEGA Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2001, 29, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.L.; Wang, K.; Chiu, I. Business-IT fit in e-procurement systems: Evidence from high-technology firms in China. Inf. Syst. J. 2008, 18, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.K. The contingent role of innovation between IT management sophistication and strategic alignment. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2009, 17, 60–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Simons, R. Performance Measurement and Control Systems for Implementing Strategies; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 17.0 User’s Guide; Amos Development Corporation: Crawfordville, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Definition | Literature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy Alignment | Strategy | Perception and acceptance of the company’s strategy | [6,7] |

| Customer | Efforts in managing information and process for customer satisfaction | ||

| Employee | Satisfaction with work results and rewards of members of the organization | ||

| Process | Executives’ level of management in work processes | ||

| Role Clarity | Goal Clarity | Extent to which members clearly understand the goals and responsibilities of work related to their jobs | [41,52] |

| Process Clarity | Extent to which members clearly understand the processes required in performing tasks related to their jobs | ||

| Engagement | Employee Engagement | Employees’ enthusiasm for work in addition to individual participation and satisfaction | [60,65,87] |

| Organizational Performance | AROE | Three-year average ROE of companies adjusted to three-year market average ROE by type of business | [88] |

| (1) Respondents by KSIC-9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KSIC Code | Name | Frequency | Percent | |

| Profit organization: | ||||

| 16 | Wood products | 4 | 1.6 | |

| 20 | Chemicals | 21 | 8.6 | |

| 21 | Basic metals | 5 | 2.1 | |

| 26 | Electronic components | 10 | 4.1 | |

| 30 | Motor vehicles | 29 | 11.9 | |

| 32 | Furniture | 5 | 2.1 | |

| 35 | Electricity supply | 9 | 3.7 | |

| 41 | Construction | 9 | 3.7 | |

| 46 | Wholesale and retail | 19 | 7.8 | |

| 49 | Transportation | 5 | 2.1 | |

| 60 | Broadcasting | 4 | 1.6 | |

| 64 | Financial | 28 | 11.5 | |

| 71 | Other professional services | 2 | 0.8 | |

| 96 | Information and communication services | 8 | 3.2 | |

| Non-profit organization: | ||||

| Public organization | 86 | 35.2 | ||

| Total | 244 | 100.0 | ||

| (2) Respondents by Position | ||||

| Position | Frequency | Percent | ||

| CEO | 2 | 0.8 | ||

| Directors | 6 | 2.5 | ||

| Heads of Department | 75 | 30.7 | ||

| Managers | 87 | 35.7 | ||

| Assistant managers | 45 | 18.4 | ||

| Staff | 29 | 11.9 | ||

| Total | 244 | 100.0 | ||

| (3) Firms by Size | ||||

| Number of employees | Frequency | Percent | ||

| Less than 100 | 22 | 9.0 | ||

| 100–249 | 34 | 13.9 | ||

| 250–499 | 46 | 18.9 | ||

| 500–999 | 43 | 17.6 | ||

| 1000–2499 | 29 | 11.9 | ||

| 2500 and over | 70 | 28.7 | ||

| Total | 244 | 100.0 | ||

| (4) Company Tenure | ||||

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std Dev. | |

| Company tenure (years) | 1 | 31 | 9.96 | 7.11 |

| Constructs | EmpEn | AROE | RCgoal | RCproc | StrAli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EmpEn | − | 1.821 | − | − | − |

| AROE | − | − | − | − | − |

| RCgoal | 2.762 | 3.270 | − | 1.051 | − |

| RCproc | 2.654 | 2.714 | − | − | − |

| StrAli | 1.067 | 1.073 | 1.000 | 1.051 | – |

| Constructs and Items | Loadings | Mean | Std. Dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StrAli: AVE: 0.744; CR: 0.920; α: 0.887 | ||||

| strategy | 0.904 *** | 9.568 | 1.479 | |

| sa_s1 | Organizational strategies are clearly communicated to members. | 0.677 *** | 5.038 | 0.961 |

| sa_s2 | Organizational strategies guide the identification of the skills and knowledge I need. | 0.700 *** | 5.006 | 0.882 |

| sa_s3 | People here are willing to change when new organizational strategies require it. | 0.787 *** | 4.924 | 0.952 |

| sa_s4 | Our senior managers agree on the organizational strategy. | 0.813 *** | 4.867 | 1.068 |

| customers | 0.780 *** | 9.187 | 1.816 | |

| sa_c1 | For each service our organization provides, there is an agreed-upon, prioritized list of what customers care about. | 0.942 *** | 4.677 | 1.294 |

| sa_c2 | People in this organization are provided with useful information about customer complaints. | 0.732 *** | 4.861 | 1.040 |

| sa_c3 | Strategies are periodically reviewed to ensure the satisfaction of critical customer needs. | 0.737 *** | 4.715 | 1.050 |

| sa_c4 | Processes are reviewed regularly to ensure that they contribute to the attainment of customer satisfaction. | 0.705 *** | 4.804 | 1.105 |

| employee | 0.856 *** | 9.115 | 1.787 | |

| sa_e1 | Our organization collects information from employees about how well things work. | 0.642 *** | 5.089 | 0.957 |

| sa_e2 | My work unit or team is rewarded for our performance as a team. | 0.800 *** | 4.494 | 1.349 |

| sa_e3 | Groups within the organization cooperate to achieve customer satisfaction. | 0.844 *** | 4.778 | 1.094 |

| sa_e4 | When processes are changed, the impact on employee satisfaction is measured. | 0.827 *** | 4.785 | 1.229 |

| processes | 0.904 *** | 9.245 | 1.619 | |

| sa_pr1 | Our managers care about how work gets done as well as about the results. | 0.699 *** | 4.614 | 1.140 |

| sa_pr2 | We review our work processes regularly to see how well they are functioning. | 0.713 *** | 4.854 | 1.024 |

| sa_pr3 | When something goes wrong, we correct the underlying reasons so that the problem will not happen again. | 0.907 *** | 4.791 | 1.031 |

| sa_pr4 | Processes are reviewed to ensure they contribute to the achievement of strategic goals. | 0.703 *** | 4.911 | 0.957 |

| RCgocl: AVE: 0.758; CR: 0.940; α: 0.920 | ||||

| rc1 | The goals and objectives for my job | 0.909 *** | 5.538 | 0.978 |

| rc2 | How my work relates to the overall objectives of my work unit | 0.890 *** | 5.487 | 0.979 |

| re3 | My duties and responsibilities | 0.898 *** | 5.709 | 0.859 |

| rc4 | The expected results of my work | 0.866 *** | 5.589 | 0.929 |

| rc5 | What aspects of my work will lead to positive evaluations | 0.784 *** | 5.342 | 1.135 |

| RCproc: AVE: 0.660; CR: 0.906; α: 0.870 | ||||

| rc6 | How to divide my time among the tasks required of my job | 0.843 *** | 5.291 | 0.996 |

| rc7 | How to schedule my workday | 0.892 *** | 5.057 | 1.039 |

| rc8 | How to determine the appropriate procedures for each work task | 0.700 *** | 4.918 | 1.190 |

| rc9 | The procedures I use to do my job are correct and proper | 0.742 *** | 5.158 | 1.016 |

| rc10 | I know the best way to do my job | 0.868 *** | 5.146 | 1.011 |

| EmpEn: AVE: 0.594; CR: 0.909; α: 0.882 | ||||

| ee1 | Performing my job is so absorbing that I forget about everything else | 0.656 *** | 4.570 | 1.149 |

| ee2 | Time passes quickly when I perform my job | 0.776 *** | 5.544 | 1.053 |

| ee3 | I really put my heart into my job | 0.871 *** | 5.475 | 0.933 |

| ee4 | I get excited when I perform well in my job | 0.795 *** | 5.310 | 1.179 |

| ee6 | I am rarely distracted when performing my job | 0.822 *** | 5.551 | 0.980 |

| ee7 | I don’t think about other things when performing my job | 0.868 *** | 5.601 | 0.980 |

| Constructs a | Mean | Std Dev. | StrAli | RCgocl | RCproc | EmpEn | AROE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| StrAli | 9.724 | 1.468 | 0.862b | ||||

| RCgocl | 5.530 | 0.850 | 0.219 *** | 0.871 | |||

| RCproc | 5.114 | 0.852 | 0.096 *** | 0.786 *** | 0.812 | ||

| EmpEn | 5.342 | 0.836 | 0.770 *** | 0.591 *** | 0.591 *** | 0.770 | |

| AROE | 10.379 | 12.887 | 0.134 *** | −0.003 | −0.065 *** | 0.142 *** | 1.000 |

| Panel A: Path Coefficients, t-Statistics, and R2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Variable | Path to | ||||

| RCgoal | RCproc | EmpEn | AROE | ||

| StrAli | 0.219 (2.597) *** | −0.080 (1.586) | −0.056 (0.845) | 0.147 (2.148) ** | |

| RCgoal | – | 0.803 (26.375) *** | 0.528 (5.795) *** | −0.081 (0.433) | |

| RCproc | – | – | 0.182 (1.865) * | −0.190 (1.135) | |

| EmpEn | – | – | – | 0.296 (2.298) ** | |

| AROE | – | – | – | – | |

| R2 | 0.048 | 0.623 | 0.451 | 0.074 | |

| Panel B: Indirect Effects and t-Statistics (Sobel’s Test) | |||||

| Latent Variable | Linkages | Path to | |||

| RCgoal | RCproc | EmpEn | AROE | ||

| RCgoal | RCproc | 0.146 (1.783) * | −0.153 (1.128) | ||

| EmpEn | 0.156 (2.065) ** | ||||

| RCproc | EmpEn | 0.054 (1.486) | |||

| StrAli | RCgoal | 0.176 (2.427) ** | 0.116 (2.194) ** | −0.018 (1.124) | |

| RCproc | −0.015 (1.197) | 0.015 (0.814) | |||

| EmpEn | −0.017 (0.698) | ||||

| RCgoal/EmpEn | 0.034 (1.640) * | ||||

| RCproc/EmpEn | 0.043 (1.502) | ||||

| RCgoal/RCproc | 0.032 (1.474) | −0.033 (0.952) | |||

| RCgoal/RCproc/EmpEn | 0.009 (1.286) | ||||

| Relationship | Sustainability Pressure a | Market Uncertainty a | Organization Type b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 117) | Low (n = 41) | │Diff.│ | High (n = 101) | Low (n = 57) | │Diff.│ | Profit (n = 158) | Public (n = 86) | │Diff.│ | |

| StrAli -> RCgoal | 0.299 (3.786) *** | 0.117 (0.693) | 0.182 (1.098) | 0.284 (2.759) *** | 0.183 (1.238) | 0.102 (0.558) | 0.168 (1.598) * | −0.130 (0.498) | 0.298 (1.396) |

| StrAli -> RCproc | −0.064 (1.104) | −0.118 (0.988) | 0.054 (0.447) | −0.102 (1.648) * | −0.031 (0.336) | 0.071 (0.637) | −0.079 (1.287) | −0.071 (0.819) | 0.008 (0.046) |

| StrAli -> EmpEn | −0.035 (0.499) | −0.100 (0.730) | 0.065 (0.449) | −0.031 (0.410) | −0.077 (0.557) | 0.045 (0.306) | −0.056 (0.658) | −0.042 (0.468) | 0.014 (0.103) |

| StrAli -> AROE | 0.127 (1.584) | 0.135 (0.657) | 0.008 (0.041) | 0.145 (1.491) | 0.145 (1.116) | 0.000 (0.007) | |||

| RCgoal -> RCproc | 0.820 (26.097) *** | 0.767 (9.643) *** | 0.053 (0.738) | 0.836 (26.409) *** | 0.773 (14.103) *** | 0.063 (1.068) | 0.779 (26.475) *** | 0.863 (23.564) *** | 0.085 (1.738) * |

| RCgoal -> EmpEn | 0.546 (5.007) *** | 0.497 (2.248) ** | 0.049 (0.209) | 0.511 (3.917) *** | 0.603 (3.364) *** | 0.092 (0.418) | 0.356 (6.549) *** | 0.542 (5.149) ** | 0.014 (0.083) |

| RCgoal -> AROE | −0.502 (0.231) | −0.106 (0.372) | 0.054 (0.128) | −0.024 (0.104) | −0.099 (0.498) | 0.075 (0.206) | |||

| RCproc -> EmpEn | 0.179 (1.473) | 0.178 (0.820) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.217 (1.528) | 0.061 (0.326) | 0.156 (0.654) | 0.146 (1.646) * | 0.361 (3.354) *** | 0.215 (1.398) |

| RCproc -> AROE | −0.297 (1.412) | −0.021 (0.121) | 0.276 (0.737) | −0.337 (1.426) | −0.021 (0.158) | 0.316 (0.928) | |||

| EmpEn -> AROE | 0.463 (2.979) *** | −0.121 (0.585) | 0.583 (2.024) ** | 0.480 (2.919) *** | −0.099 (0.764) | 0.579 (2.439) *** | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kwon, H. The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions of Strategic Alignment on Sustainability: An Empirical Investigation of Korean Firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104180

Kim J, Kim H, Kwon H. The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions of Strategic Alignment on Sustainability: An Empirical Investigation of Korean Firms. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104180

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jinhwan, Hyeob Kim, and HyukJun Kwon. 2020. "The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions of Strategic Alignment on Sustainability: An Empirical Investigation of Korean Firms" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104180

APA StyleKim, J., Kim, H., & Kwon, H. (2020). The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions of Strategic Alignment on Sustainability: An Empirical Investigation of Korean Firms. Sustainability, 12(10), 4180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104180