Change Management, Digital Maturity, and Green Development: Are Successful Firms Leveraging on Sustainability?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. Research Instrument

3.2. Construct Definition

3.2.1. Change Management

3.2.2. Digital Maturity

3.2.3. Business Performance

3.2.4. Green Development

3.3. Sample Description

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Model Measurement

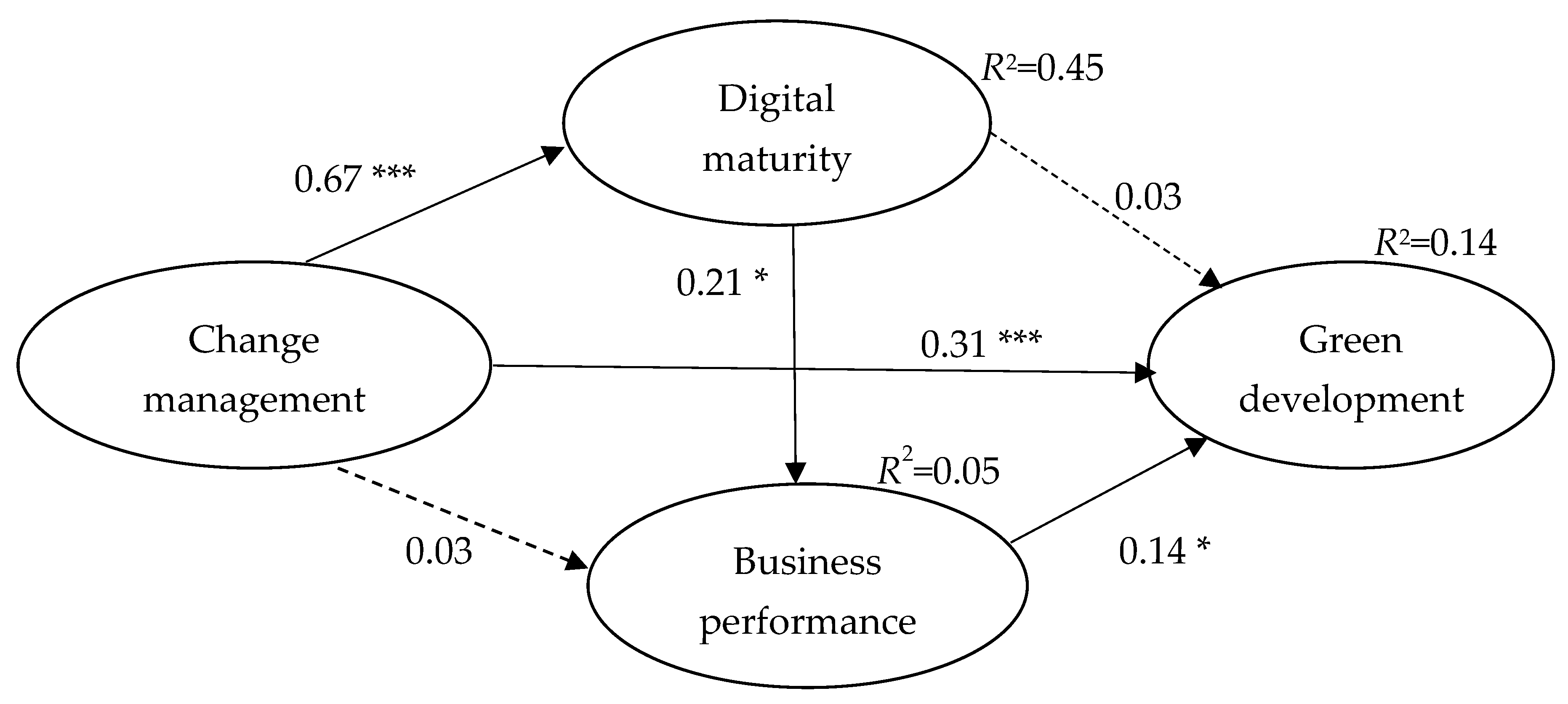

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rafferty, A.E.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Armenakis, A.A. Change readiness: A multilevel review. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A.M.; Woodman, R.W.; Cameron, K.S. Studying organizational change and development: Challenges for future research. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 697–713. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, M.K.; Kraft, C.; Lindeque, J. Strategic action fields of digital transformation. An exploration of the strategic action fields of Swiss SMEs and large enterprises. J. Strategy Manag. 2020, 13, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukko, J.; Nasiri, M.; Saunira, M.; Rantala, T. Sustainability strategy as a moderator in the relationship between digital business strategy and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Su, F.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 2017, 28, 1129–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, K.J.; Hwang, T.; Gregor, S. An integrative model of IT-enabled organizational transformation. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 1755–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Lock, I. The game-changing potential of digitalization for sustainability: Possibilities, perils, and pathways. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. The Relationship between BPR Strategy and Change Management for the Sustainable Implementation of ERP: An Information Orientation Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripsas, M.; Gavetti, G. Capabilities, cognition and inertia: Evidence from digital imaging. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R.A. Hyper-competition; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Szerb, L.; Acs, Z.; Autio, E.; Ortega-Argiles, R.; Komlosi, E. REDI: The Regional Entrepreneurship and Development Index—measuring Regional Entrepreneurship. 2013 Final report. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/studies/pdf/regional_entrepreneurship_development_index.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Desai, S. Entrepreneurship and economic development in cities. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2015, 55, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Stam, E.; Audretsch, D.B.; O’Connor, A. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; McAdam, D. Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields. Sociol. Theory 2011, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, H.; Chia, R. On Organizational Becoming: Rethinking Organizational Change. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Dowell, G. A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Managing the Business Case for Sustainability. In The Integration of Social, Environmental and Economic Performance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Konar, S.; Cohen, M.A. Does the Market Value Environmental Performance? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2001, 83, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M.D.; Molina-Azorin, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E. The whole relationship between environmental variables and firm performance: Competitive advantage and firm resources as mediator variables. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3110–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Meng, X.; Yin, H.; Tam, C.M.; Sun, L. Impact of cleaner production on business performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G.R.; Treviño, L.K.; Cochran, P.L. Integrated and decoupled corporate social performance: Management commitments, external pressures, and corporate ethics practices. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Morioka, S.N.; Carvalho, M.M. A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr.; Peter, J.P. Research design effects on the reliability of rating scales: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1984, 21, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Green Human Resource Management as a Tool for the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: Polish Young Company Experience. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Zhang, X.P.; Yuan, J.; Naz, S.; Maqbool, S. Impact of a balanced scorecard as a strategic management system to improve sustainable development: Measuring the mediation of organizational performance through PLS-Smart. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); Sage: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, M.; Rowland, D. Building change leadership capability: ‘The quest for change competence’. J. Chang. Manag. 2000, 1, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agárdi, I. A digitalizáció mint a kiskereskedelmi tevékenységet integráló tényező. Vezetéstudomány 2018, 12, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remane, G.; Hanelt, A.; Wiesboeck, F.; Kolbe, L. Digital maturity in traditional industries–An exploratory analysis. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimarães, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B. Managerial perceptions of marketing performance: Efficiency, adaptability, effectiveness and satisfaction. J. Strateg. Mark. 2000, 8, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeling, A.; Himme, A. When does market share matter? New empirical generalizations from a meta-analysis of the market share-performance relationship. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; Heinemann, F.; Brettel, M.; Hungeling, S. Configurations of resources and capabilities and their performance implications: An exploratory study on technology ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1337–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.N.; Hanks, S.H. Measuring the performance of emerging businesses: A validation study. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, L.; Vinci, C.P. Green economy and sustainable development: The economic impact of innovation on employment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of green inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes-Nagy, J.; Tagai, G. Regional inequalities and the determination of spatial structure. Reg. Stat. 2011, 14, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Economic Surveys: Hungary; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rechnitzer, J.; Berkes, J.; Filep, B. The most important city development initiatives of Hungary. Reg. Stat. 2019, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barta, G.; Lőcsei, H. The effect of the recent economic crisis on the spatial structure of Hungarian industry. Reg. Stat. 2011, 14, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigne, E.; Aldas-Manzano, J.; Curras-Perez, R. A scale for measuring consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility following the sustainable development paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chau, K.W.; Wang, H.; Pan, W. A decade’s debate on the nexus between corporate social and corporate financial performance: A critical review of empirical studies 2002–2011. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modelling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakovirta, M.; Denuwara, N. How COVID-19 redefines the concept of sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | Percentage of Firms |

|---|---|---|

| Number of employees | 10–49 employees | 44.2% |

| 50–99 employees | 24.8% | |

| 100–259 employees | 20.0% | |

| over 250 employees | 13.0% | |

| Ownership | Hungarian state-owned firms | 5.3% |

| Hungarian private firms | 74.3% | |

| Foreign-owned private firms | 20.4% | |

| Type of settlement | County seats | 46.9% |

| Cities | 33.0% | |

| Other settlements | 17.4% |

| Construct | Green Development | Business Performance | Digital Maturity | Change Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Development | 0.8389 | |||

| Business Performance | 0.0395 | 0.8744 | ||

| Digital Maturity | 0.0701 | 0.0504 | 0.9197 | |

| Change Management | 0.1209 | 0.0273 | 0.4492 | 0.8228 |

| Construct | Green Development | Business Performance | Digital Maturity | Change Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Development | ||||

| Business Performance | 0.2148 | |||

| Digital Maturity | 0.2839 | 0.2389 | ||

| Change Management | 0.3788 | 0.1737 | 0.7084 |

| The Hypothesed Path | β | t-Values | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Performance→Green Development (Hypothesis 6) | 0.1419 | 1.9479 | 0.0257 |

| Digital Maturity→Green Development (Hypothesis 5) | 0.0283 | 0.3498 | 0.3632 |

| Digital Maturity→Business Performance (Hypothesis 4) | 0.2066 | 2.3425 | 0.0096 |

| Change Management→Green Development (Hypothesis 3) | 0.3053 | 3.5313 | 0.0002 |

| Change Management→Business Performance (Hypothesis 2) | 0.0268 | 0.2478 | 0.4021 |

| Change Management→Digital Maturity (Hypothesis 1) | 0.6702 | 17.4531 | 0.0000 |

| Effect | Beta | Indirect Effects | Total Effect | p-Value | Cohen’s f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business Performance→Green Development | 0.1419 | 0.1419 | 0.0257 | 0.0223 | |

| Digital Maturity→Green Development | 0.0283 | 0.0293 | 0.0576 | 0.2362 | 0.0005 |

| Digital Maturity→Business Performance | 0.2066 | 0.2066 | 0.0096 | 0.0248 | |

| Change Management→Green Development | 0.3053 | 0.0424 | 0.3477 | 0.0000 | 0.0598 |

| Change Management→Business Performance | 0.0268 | 0.1384 | 0.1652 | 0.0222 | 0.0004 |

| Change Management→Digital Maturity | 0.6702 | 0.6702 | 0.0000 | 0.8154 |

| Construct (Rho) | Statements | Mean | Standard Deviation | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business performance (ρA = 0.891) | The growth rate of revenue-to profit. | 3.42 | 0.802 | 0.9020 |

| The growth rate of Return on Equity. | 3.36 | 0.694 | 0.9678 | |

| Our market share growth rate in comparison with other firms in our industry. | 3.30 | 0.614 | 0.9343 | |

| Change management (ρA = 0.868) | In our company, change management is recognized as part of our corporate culture. | 3.17 | 1.090 | 0.8854 |

| Our firm has the capability to manage strategic change in ongoing processes. | 3.14 | 1.163 | 0.9253 | |

| Our managing directors/founders are constantly looking for innovation opportunities. | 3.61 | 1.040 | 0.8965 | |

| In comparison with our competitors, our company has significantly more capability in change management. | 3.27 | 1.012 | 0.9206 | |

| Digital maturity (ρA = 0.814) | In comparison with other firms in our industry, digital solutions in our firm are more developed. | 3.00 | 0.935 | 0.9635 |

| In comparison with our competitors, digital transformation in our firm is substantially more advanced. | 3.02 | 0.918 | 0.9744 | |

| Our firm is a leader in digital transformation within the sector. | 2.95 | 0.963 | 0.9387 | |

| Green development (ρA = 0.833) | Our firm is committed to invest in public sector development projects in green energy. | 1.60 | 0.874 | 0.9195 |

| Our firm is committed to invest in public sector development projects in waste-management. | 1.61 | 0.913 | 0.9259 | |

| Our firm is committed to invest in public sector development projects in green environmental development (e.g., parks). | 1.64 | 0.886 | 0.9022 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irimiás, A.; Mitev, A. Change Management, Digital Maturity, and Green Development: Are Successful Firms Leveraging on Sustainability? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104019

Irimiás A, Mitev A. Change Management, Digital Maturity, and Green Development: Are Successful Firms Leveraging on Sustainability? Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104019

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrimiás, Anna, and Ariel Mitev. 2020. "Change Management, Digital Maturity, and Green Development: Are Successful Firms Leveraging on Sustainability?" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104019

APA StyleIrimiás, A., & Mitev, A. (2020). Change Management, Digital Maturity, and Green Development: Are Successful Firms Leveraging on Sustainability? Sustainability, 12(10), 4019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104019