1. Introduction

The importance of implementing the European Union (EU) environmental policy and related legislation has gained considerable attention and traction recently in both the European Commission (EC) [

1,

2] and academia. For example, the EC recently compiled data to help explain the reasons for deficits in environmental policy implementation [

3]. Some of the specific deficits that were examined included ineffective coordination and the lack of capacities among authorities, as well as insufficient compliance and policy coherence. In undertaking implementation research, a large number of EU scholars have dedicated considerable resources to study how EU environmental law is being implemented nationally and, in some cases, even regionally and locally [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Much of this research has likewise studied compliance with EU legislation [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] or, in more recent contexts, also the dismantling of EU environmental policies, specifically focusing on what happens after legislative adoption [

3,

19].

In general terms, four waves of implementation have occurred in research, with each wave focusing on different aspects [

6]. During the first wave, scholars principally focused on the theoretical argument of “the “stickiness” of deeply entrenched national policy traditions and administrative routines, which poses great obstacles to reforms aiming to alter these arrangements” [

7] (p. 89). This meant that “downloading” to the national level of particular policies from the EU framework was viewed as particularly difficult if the “uploading” to the EU level of one’s own policies was obstructed [

12]. This degree of fit or misfit between the requirements of the new EU and existing domestic rules and traditions to test the implementation performance of Member States was at the heart of the second implementation wave of EU implementation studies [

10,

11,

20,

21,

22], although the results were later contested [

16,

23]. The third implementation wave was principally concerned with exploring the options to adopt a larger plurality of theoretical and methodological approaches, including the first quantitative studies, which drew heavily on data from the compliance literature [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Many of those studies, however, remain case-specific or used existing data compiled on the European level to study compliance and transposition, but did so without studying national contexts and different national policies simultaneously. The fourth and most recent implementation wave includes both qualitative and quantitative studies [

6]. While some of these have explored the further transposition of EU law to the Member States from a comparative perspective, others have studied the Member States’ reactions to rulings from the Court of Justice. Treib (2014) explains that these studies were based on the idea that if Council members were opposed during the voting procedure, these members’ countries would also object to the transposition of the legislation once it has been adopted. More recent research has concentrated on the role of citizens and non-governmental organizations in law enforcement [

32], as well as the EC’s role in the post-legislative phase [

3,

19].

With a broad view of the implementation literature in mind, all studies to date have seemingly concentrated on the implementation of legally binding EU instruments. Some have studied transposition, while others have studied legal and policy compliance [

33,

34,

35]; however, how the non-legally binding (or soft) policy instruments (e.g., strategies) are being implemented by EU Member States from a comparative perspective has not been researched systematically to date. This paper seeks to address this research gap by analyzing how the EU Forest Action Plan, covering the 2007 to 2011 period, was taken up by countries as part of implementing the EU Forestry Strategy [

36,

37]. This is deemed as particularly relevant now, as it has been more than 10 years since the initial implementation of the Forest Action Plan and the period since then has been especially interesting, given that so many new countries have joined the EU. These events present a unique period of EU enlargement that allows for meaningful insight into the uptake of a soft policy instrument by new and old EU Member States. The Forest Action Plan can accordingly reveal more about the Europeanization of forest policy than, for example, the more recent Multi-Annual Implementation Plan of the EU Forest Strategy (Forest MAP) [

38,

39,

40]. Moreover, given recent developments with regard to the European Green Deal, forest policy has once again found a place in the EU Agenda setting process [

41], including the development of a third EU Forest Strategy, measures to support deforestation-free value chains, and a suggested revision of the Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry Regulation (LULUCF) in 2021.

The primary reason for returning to the first Forest Action Plan is to gain a better understanding of how it translated into an EU Member State context. Moreover, most articles concerned with the analysis of forest-relevant policies in the EU focus on analyzing EU decision-making impacts on a national level [

42,

43,

44], or vice versa [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], but not how Member States actually embrace EU strategies from a comparative perspective. This paper addresses, to some degree, this empirical gap and provides insight into whether Europeanization effects are comparable, irrespective of whether EU Member States are deciding upon and implementing a legally binding or non-legally binding EU policy instrument. The EU Forest Strategy is particularly relevant from a sustainability perspective, as it is designed to ensure that the multi-functional potential of EU forests is managed sustainably, including the efficient use of natural resources.

The structure of this paper is as follows: a start is made with a broad background description of EU forest policy and its action plan before the conceptual framing of the paper is presented by utilizing Europeanization and implementation literature. Here in particular, Börzel’s up- and downloading of policy objectives as interconnected to the forest-related decision-making process and its implementation through Member States [

12] will be drawn upon. After setting out the methods applied, the article then explores the strategies used for implementing the EU Forest Strategy where the EC does not have enforcement opportunities. The findings are compared across Member States and the implications are elucidated in light of the conceptual framework.

2. Background: European Forest Governance through the Implementation of the EU Forest Action Plan

The first EU Forest Strategy was adopted in 1998, providing general guidelines for an EU forest policy designed to coordinate other EU forest-related policies [

36]. The strategy employed key principles related to Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) and addressed several issues, which included competitiveness, job creation, forest protection, and delivering forest ecosystem services through a multi-functional approach. It explicitly noted the domains of EU competence, as well as relevant processes and platforms, through which, coordination should take place, examples being the Standing Forestry Committee (SFC), the Civil Dialogue Group on Forestry and Cork, and the Expert Group on Forest-based industries and Sectorally Related Industrial issues. The second EU Forest Strategy was adopted in 2013 in response to the additional challenges that were identified as facing forests and the forest-based sector [

39]. The second strategy served as an updated and integrative framework in response to the increasing demands placed on forests, while addressing changes in societal and policy priorities since the introduction of the first strategy. Further in depth analyses and reviews of European forest governance can be found in Pülzl et al. [

46], Winkel and Sotirov [

48], Aggestam et al. [

50], Aggestam and Pülzl [

51], Lazdinis, Angelstam and Pülzl [

49], Wolfslehner et al. [

38] and [

52].

The implementation of the first strategy was done through the Forest Action Plan for the 2007 to 2011 period [

37] and remained on the level of voluntary cooperation between Member States (no enforcement capabilities), with some coordinating actions being implemented by the Commission. The Action Plan focused on four main objectives:

Improve long-term competitiveness.

Improve and protect the environment.

Contribute to the quality of life.

Foster coordination and communication.

Additionally, a further 18 related key actions were proposed by the Commission to be implemented jointly with EU Member States during this period [

37].

It can be argued that the Forest Action Plan helped to establish a workable EU-wide framework for forest-related actions as it called for, amongst other things, an improved form of coordination and cooperation on forest-related issues, even though its main contribution was the summary of ongoing forest-related activities in the EU at the time [

53].

Europeanization as a Part of the Downloading and Uploading of EU Forest-Relevant Policy

In order to avoid following a strict hierarchical top-down implementation approach, this paper will take both a top-down and bottom-up perspective [

13], which then necessitates the consideration of how EU Member States were involved in uploading their priorities into EU forest policymaking. This is based on a more dynamic view of the Europeanization process [

54]—one where an interconnected and continuous flow of the up- and downloading of policy positions and preferences exists between the EU and its Member States [

12,

55].

Summarizing the contributions to a recent collection in the Journal of European Public Policy, Thomann and Sager [

5] stated that the “characteristics of policies, in interaction with domestic political contexts, determine the responses of members states to EU policy” (p. 6). Thomann and Sager further argued that the implementation of EU policy is significantly affected by (a) the flexibility in implementation (e.g., customization patterns related to binding policies), (b) the capacities of enforcement (e.g., vertical implementation competencies), and (c) the motivation of implementing agents (e.g., interest constellations on the ground). However, these are factors principally affecting the implementation dynamics of binding EU policies across governance levels (both nationally and internationally). This would imply that the performance from an EU implementation perspective for a non-binding policy, such as the Forest Action Plan, would be very poor (e.g., due to the lack of enforcement capabilities). In this regard, Börzel [

12] defined three strategies that the Member States adopt regarding implementation, as summarized below in

Table 1.

Drawing inspiration from Börzel [

12], the main hypothesis for this paper to explain the uptake of the Forest Action Plan is that EU Member States either engage in “pace-setting”, “foot-dragging”, or “fence-sitting” (see

Table 1). Furthermore, this response is predicated less on the actual policy instrument, per se, but rather on the perceived importance of the national forest-based industry and/or the actual forest resources available. Both factors relate more to the motivation of the implementing agent rather than the flexibility or enforcement capacities associated with the implementation of the Forest Action Plan. As the Member States’ forest resources and the importance that they place on their respective forest sectors vary across the EU, we test the hypotheses based on Börzel’s framework of how Member States implement the Forest Action Plan.

The main hypothesis essentially relates to the idea that forest-rich EU Member States with significant forest-based industries have been more active in uploading their own national priorities on the EU level (pace-setting), which they hope will result in an EU policy with a minimal degree of misfit when downloaded for national adaptation. One could reasonably expect that foot-dragging is a less prevalent strategy for the Member States given the non-binding nature of the Forest Action Plan. It should further be noted that the majority of fence-sitting is likely related to national priority setting, where, for example, countries in Southern Europe may be more interested in measures addressing forest fires as compared to Northern Europe.

3. Method

This paper is based on a document review, an evaluation survey that was conducted, and interviews. Data was primarily collected for the Ex-post Evaluation of the EU Forest Action Plan [

53]. The document review was undertaken using the official documentation of the Forest Action Plan and its implementation. Some of the documents were publicly available; meeting and working group materials that were not publicly available were collected during the official evaluation of the Forest Action Plan [

53]. Meeting documentation of the Standing Forestry Committee (SFC), the Advisory Group on Forestry and Cork (nowadays the Civil Dialogue Group on Forestry and Cork), and the Inter-services’ Group on Forestry were analyzed. The reviews of official documents of the European Council and the European Parliament were based on internet-based document registers (e.g.,

https://eur-lex.europa.eu). In addition to the foregoing, materials from relevant stakeholders, including the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions, were reviewed.

The evaluation survey and interviews targeted three groups: namely, the European Commission Services, forest-relevant agencies and various ministries of individual Member States, as well as relevant stakeholders (see

Supplementary Materials for the three respective surveys). The Commission was a leading actor in the implementation of the Forest Action Plan, and the Commission survey was thus constructed to go through all the action plan’s activities. Staff from sixteen Commission departments and services were interviewed, in total, across eight Directorate-Generals (Agriculture and Rural Development, Climate Action, Environment, Health and Food Safety, Research and Innovation, Energy, Eurostat and the Joint Research Centre). The Commission respondents were selected based on their work on specific key actions stemming from the EU Forest Action Plan. In practice, the interviews, therefore, focused on asking questions that were relevant to the respondent’s work in relation to the Forest Action Plan, as well as addressing any issues that became apparent as a result of their survey responses. Interviews (conducted both in person and over the phone) were carried out between January and March, 2012, and an additional analysis and review of these interviews were carried out in 2019.

The EU Member State survey included an inventory of the Forest Action Plan activities, where they were asked to indicate their degree of progress in relation to its work program. It also included an assessment of the action plan’s implementation, its relevance, and the relationship of the relevant national forest program (NFPs) and national forest policy to the Forest Action Plan. The survey questionnaire was distributed through the SFC and additional phone interviews were conducted to collect additional data between January and March in 2012. Responses were received from 25 Member States (all EU countries except Belgium and Malta, Croatia was still not an EU Member State at this point) filled in by the national focal points in charge of coordinating the implementation of the EU Forest Action Plan at the national level.

The stakeholder survey was distributed as an online survey with targeted invitations sent to the Advisory Group on Forestry and Cork and to stakeholders from outside the actual implementation of the Forest Action Plan. Whilst there was an open registration to contribute to the survey, the distribution list itself consisted of 356 e-mail addresses, with the addressees being drawn from the main forest-relevant stakeholder organizations. Moreover, interviews were conducted in order to complete the data collection, where deficiencies were identified, and to which a total of 51 responses were received. Six of these responses were submitted as organizational responses, having been compiled by several respondents. The stakeholder responses can be categorized as follows: producers (45.1%), traders, operators, industry, and workers (15.7%), environmental organizations (17.6%), and other stakeholders (21.6%). “Other stakeholders” were mainly research and technology-related organizations.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Perceived Relevance of the EU Forest Strategy and Action Plan

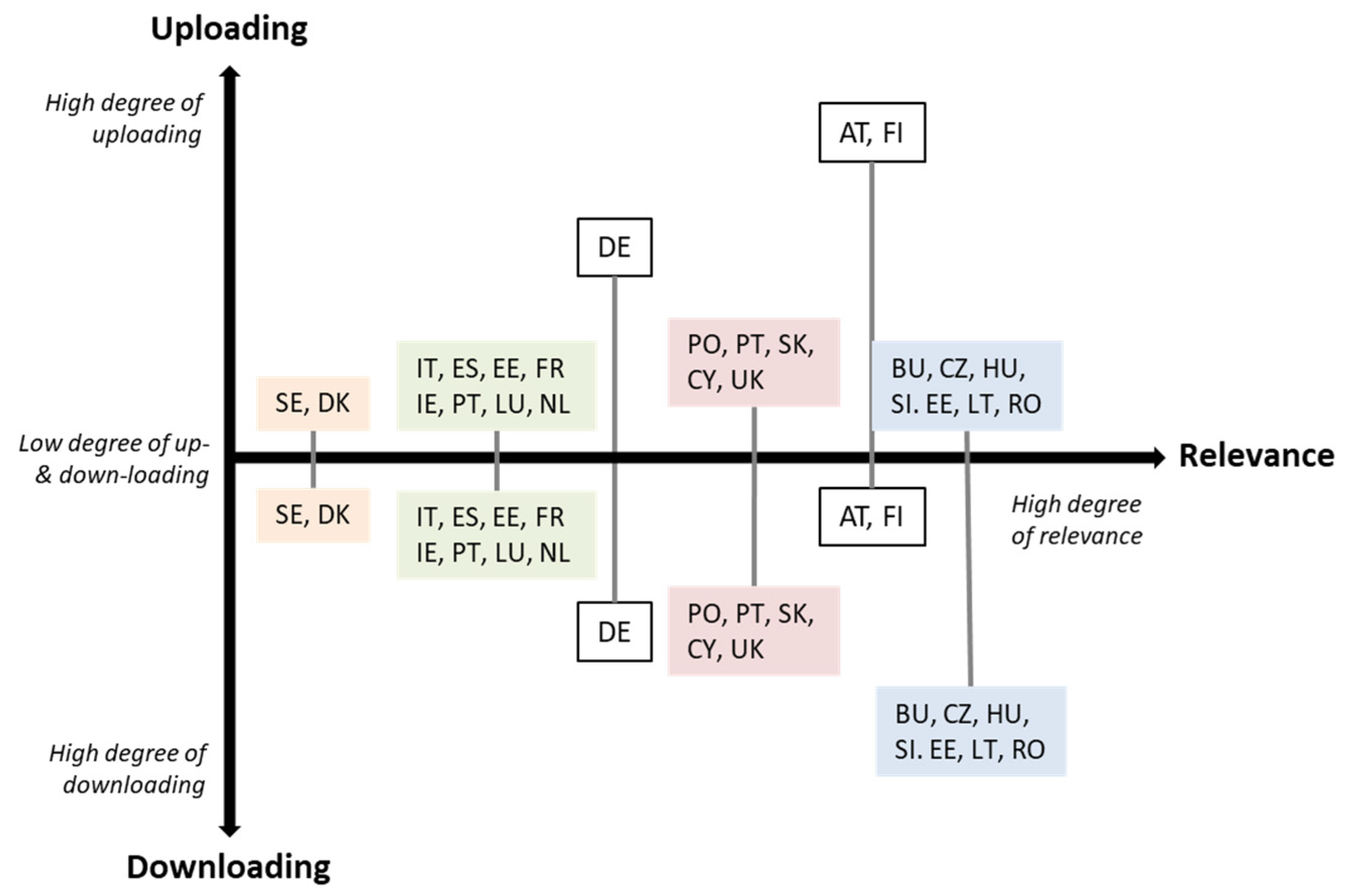

The results from the evaluations indicated that the EU Member States differed significantly in the perceived effects associated with the Forest Action Plan (see

Figure 1).

Some Member States with high forest cover—particularly Austria, Slovenia, and Spain—attributed a significant degree of relevance to the Forest Action Plan and its objectives, a position which starkly contrasted to the ‘of no importance’ view expressed by Finland and Sweden. This was an interesting result, given that Sweden and Finland not only represent a significant share of Europe’s forests, but each also maintain an impressive forest-based industry. A second observation that could be made was that Eastern European countries that had just joined the EU and also held a significant share of European forests (e.g., Poland and Romania) only ascribed medium significance, whereas the plan was rated highly in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Remarkably, the perceived effects of the plan were also surprisingly high in France and the United Kingdom, while it was considered as rather unimportant in Germany and The Netherlands.

These results provided a heterogeneous picture that did not conform to the notion that the EU Forest Strategy would be important in countries with high forest cover. These differences may not necessarily be as surprising as they appear at first glance for two reasons: (1) the economic importance and role of forest-based industries vary significantly across these countries [

46,

56,

57,

58,

59]; and (2) the EU Forest Strategy is a non-binding and voluntary policy instrument [

38,

51,

53]. Nevertheless, in contrast to our hypothesis, this would suggest that Member States that have a strong forest-based industry may simply choose to ignore the strategy, especially if it does not fit well with their national priorities.

4.2. Downloading vs. Uploading the EU Forest Action Plan

With regards to downloading, most EU Member States (approximately 70 percent) indicated that the Forest Action Plan had an actual impact on national forest policy (see

Figure 2), particularly in the development of national forest programs (NFPs). The main reasons for using the plan ranged from providing a neutral tool (or text) that actors at the national level could use to avoid conflicts, through to some Member States using it to provide an easily downloadable set of objectives that could be taken up at the national level without adding to the local workload: essentially, a work saving copy-paste. There were also instances where the Forest Action Plan was used as a reference point for forest development plans or other similar activities.

Notably, the establishment of NFPs preceded the Forest Action Plan in several countries, while in others, it became part of the accession process and could be attributed to the Europeanization of national forest policy [

53]. In fact, based on the input received through the survey, several Member States specified that their NFPs referred directly to the objectives of the Forest Action Plan. However, this position was far from universal, as some respondents referred only to the community level implementation, while others pointed out that it was difficult to isolate activities that could be attributed in some way to the Forest Action Plan at a national level.

Based on the analysis of the quantitative data, the Member States could be divided into three groups:

- A.

Countries (AT, CZ, SL, HU, RO, GR, MT, LT, LV, ET) where the Forest Action Plan had a significant impact and where a high degree of compliance and cohesion between the EU and national strategies was sought. Some of these countries used the plan as a basis for defining a structure or concrete measure in their own national forest strategies, NFPs, or in development strategies for their forest sector. This included cross-references between the EU and national policy documents and implementation during the 2007–2011 period. It was particularly observable that Eastern and South-Eastern European Member States used the Forest Action Plan as a template to shape their NFPs, which may be due to their simultaneous development and implementation. This allowed the Forest Action Plan to influence NFP definitions and implementation.

- B.

Countries (FI, DE, SK, PL, UK, PT) where the national forest policy process was seen as more independent from the EU and where the impacts from the Forest Action Plan have been more indirect in nature. For example, most Member States (≈60%) reported that the plan had only been utilized as a reference point to check and/or update national strategies, meaning that it became an additional factor rather than a key influencer of national processes in preparing development plans, carrying out evaluations, highlighting communication and education measures in NFPs, fostering cooperation and participation through NFPs, addressing the role of ecosystem services and non-wood forest goods and services, supporting forest owners’ cooperation and advisory services, and so forth. The same applied to the inclusion of forestry measures in Rural Development Programmes, national timber procurement policies, and frameworks for defining a bio-energy strategy, etc.

- C.

Countries (SE, DK, BE, NL, LX, FR, IR, ES, IT) where no added value was produced nor expected from the Forest Action Plan. These countries highlighted that the plan was a useful tool to enhance coordination and policy formulation on community policies affecting the forest-based sector, but, as such, was not directly relevant for forest policies on a national level.

Within each of the country groups, there were considerable differences in terms of forest resources (both forest-rich and biodiversity-rich Member States in each group) and in terms of the relative importance that forest-based industries played within a State (e.g., FI, SE, and AT were categorized into different groups). In addition, the groups also differed in terms of location (neither only Eastern, Southern, or Central European countries in one group), and forest ownership (both public owners only and public and private ownership structures were present). Therefore, it cannot be said that these groups related to forest resource availability nor forest-based industry importance at a national level. This contrasted with our main hypothesis and to what many other scholars have argued in the past.

Based on the interviews and document analysis (including the informal documents), the results also demonstrated that some countries (AT, FI, and DE) have been active in uploading their priorities to the EU decision-making process with regards to the development of the Forest Action Plan (see

Figure 3), while others have been active in downloading activities (PO, PT, SK, CY, UK, and BU, CZ, HU, SI, EE, LT, and RO).

It would also be relevant to note some inconsistencies in the above-suggested grouping. For example, in the case of Austria, the Forest Action Plan was seen as relevant, but it was considered to have no impact on the national forest policy (see

Figure 2). This suggests contradictions in terms of the degree of importance attached to the plan vis-a-vie national forest policy priorities. Austria was, nevertheless, included in group A based on the overall relevance attached to the plan and its active role in uploading even though it did not significantly engage in downloading. Similar arguments applied to Finland, where some impacts were reported, but it was not seen as particularly relevant at a national level; hence, it was part of group B. These variations are reflected in

Figure 3.

There was also a third group of countries (SE, DK, IT, ES, EE, FR, IE, PT, LU, and NL) that were considered as neither active in up- nor downloading. Germany was also an outlier here, as it was both active in uploading and downloading, but, at the same time, perceived the Forest Action Plan as not particularly relevant (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). One distinction to be made here that may help to clarify this seeming inconsistency is that Germany is a federal republic, and both the Forest Action Plan and the strategy could be used as neutral documents that all the federated states could agree upon without needing further negotiation. It was, thus, a useful work-saving instrument that could be used in the German context.

4.3. Actual Implementation Strategies Associated with the EU Forest Action Plan

The analysis demonstrates that our main hypothesis cannot be supported. Not all forest-rich countries attributed a significant degree of relevance to the Forest Action Plan, including countries, such as Finland and Sweden, which have very substantial forest-based industries. The analysis furthermore demonstrates that the degree of relevance attached to the plan did not necessarily affect either the policy implementation or the national forest policy, such as was the case with Austria. Three groups of countries were identified that did not adhere to the types identified by Börzel (see

Table 1) during the downloading phase. The newly acceded states in Eastern Europe especially demonstrated a predilection to downloading the Forest Action Plan—as with Austria, the outlier in the group that was not expected to so enthusiastically implement it given its efforts in uploading its own policy priorities during the formulation process. Sweden, Denmark, the Benelux, and most Mediterranean States neither implemented nor expected an impact from the Forest Action Plan. Finally, with regards to the uploading of national perspectives, the analysis showed that uploading was not necessarily linked to downloading; such was seen in Germany’s case, while other Member States downloaded more than others even though they had engaged in comparable uploading.

The findings provided a more heterogeneous picture, whereby none of the implementation strategies identified by Börzel applied neatly. This implied the need to refine the implementation categories identified by Börzel (2002) when applied to soft policy instruments. Efforts by countries to either up- or download (or not) revealed more variation in their non-binding implementation processes compared to those involving legally binding regulations and/or directives.

Table 2 outlines some of the additional elements that would need to be considered for the implementation of a soft policy instrument.

More precisely, it is argued here that countries either engage in the drafting of forest policy at the EU level (uploading) and/or choose to shape national policies based on an EU policy (downloading):

“Dual-driving” relates to a Member State that both uploads and downloads, thus, being interested in both setting the agenda at an EU level while utilizing the resultant plan to mold national forest policymaking. While no clear-cut example of this can be found in the available data, Germany best typifies this type of implementation strategy.

“Front-runner” (similar to Börzel’s pace-setter) is not characterized by the desire to avoid implementation costs (even though this may factor into the overall equation), but rather by the intent to affect EU policy prioritization in a given domain (forests), which necessarily requires uploading one’s own priorities. In addition to this, the political will exists to affect policymaking in other EU Member States, and this entails efforts to export a specific view on forests while avoiding having the final EU policy overly affect the national priority setting.

“Catching-up” relates to the Member States where pre-existing changes were ongoing at the time in question, such as recent ascension countries or, in the specific context of this paper, during the initial establishment of NFPs or the development of national forestry strategies, in which, the Forest Action Plan played a major role. These countries were, for this reason, primarily involved in downloading the EU policy. Data from a more recent evaluation of the Forest MAP [

38] suggest that these countries have now moved on from the “catching up” phase and it is, as such, a temporally specific category.

“Non-participatory” Member States encompass two types of countries: (1) EU Member States where the forest-based sector is not very relevant and where the need for a forest policy at the EU level is questioned. In such cases, EU instruments, such as the Forest Action Plan, will most likely be used as a basis for setting a discussion agenda at a national level; (2) Member States where the forest sector is well developed, but no relevance is assigned to instruments, such as the Forest Action Plan; for example, the plan did not offer any complimentary aspects to pre-existing activities. In both cases, non-binding instruments, such as the Forest Action Plan, can be expected to have limited to no impact.

“Foot-dragging,” “fence-sitting,” and “pace-setting” (see

Table 1) are, in the context of this research, not applicable, as there are no direct costs associated with the implementation of a voluntary instrument. In part, this is because of the absence of any enforcement mechanism and the lack of risk associated with non-compliance (e.g., implementation costs are not necessarily a factor affecting behavior), but also the increased flexibility inherent in the implementation of soft policies (e.g., allowing national interests to steer implementation).

5. Discussion: Under What Conditions Do Soft Instruments Have an Impact on the National Level?

The implementation of the EU Forest Action Plan demonstrate that when the EU and national policy goals dovetail well, a significant degree of downloading from an EU policy domain to a national level can occur. In line with earlier findings [

38,

51,

59], actions taken by EU Member States correlated with the relevance each attached to the plan. For example, the extent of downloading by groups A and B suggests a gradient (with some exceptions) between relevance, uploading, and downloading. This gradient is not fully reflected in

Figure 3, as this is based on a qualitative analysis of the documents and interview data. The Member States in group C present a markedly different category that does not conform to this picture. More specifically, group C contains countries that have national policies that were already well aligned with the Forest Action Plan. For example, in Sweden, it was argued that the plan did not add anything new to the national forest policy. In other States, countries simply had no interest in the plan, irrespective of whether it fit or not with national policy goals, and this is reflected in the fact that hardly any up- or downloading occurred for countries in group C. The implementation literature suggests that this behavior occurs to avoid adaptation costs; however, this does not apply to the Forest Action Plan, as it lacked any enforcement mechanisms. Arguably, any decision to up- or download is more likely based on a desire to influence the agenda or to conform to EU policy objectives. It is presumed that this is particular to voluntary policy instruments, such as the Forest Action Plan.

The gradient in terms of up- and downloading ranges from Member States that have been engaged in formulating the Forest Action Plan but are inactive in downloading it, to those that have largely embraced the plan in the development of their own national forestry strategies and programs (e.g., EU accession countries). However, the subsidiarity and proportionality principles apply to EU forest policy. This means that principles of subsidiarity and proportionality (Article 5 of the EU Treaty) govern the exercise of the EU’s competences, which aims to ensure that decisions are taken as closely as possible in conjunction with the citizenry. Having this background in mind, it should be noted that it is difficult to attribute direct effects to the Forest Action Plan, either at national or sub-national levels (where policy and practice respond to various and diverse national and sub-national drivers). This makes the relationship between up- and downloading less clear, whilst simultaneously suggesting that the categories proposed by Börzel [

12] are inadequate to explain Member State behavior with regards to implementing soft policy instruments (see

Table 1). It also supports the view that the degree to which countries align with the Forest Action Plan can be decoupled from their involvement in up- and downloading. This means that if a Member State does not assign any direct relevance to a non-binding and voluntary EU strategy or action plan, it does not matter whether it is already aligned with the associated policy priorities at the EU level.

Considering the varying degrees of relevance that different Member States have attached to the Forest Action Plan allows us to further refine how the States are categorized. First, when considering soft policy instruments, the degree to which a State aligns would only be relevant in cases where there is a national interest in downloading. This is, for example, the case in Eastern European countries that were (particularly at this time) still playing catch-up, and in some Southern and Central European countries, where the plan played a role in establishing NFPs or re-developing national forest strategies. In both cases, the Forest Action Plan provided a valuable reference point for discussion at a national level, as well as offering a framework that could be readily downloaded with no or little direct costs (e.g., human and financial). As a supporting factor in this argument, it was noted in some cases that having a ready and seemingly neutral policy instrument at the EU level made discussions at the national level substantially easier as the Forest Action Plan was perceived as being somewhat disconnected from domestic politics.

Foremost amongst the findings, and again in contrast to our main hypothesis, neither the degree of forest cover nor the national importance of forest-based industries was a determining factor for how a Member State behaved. For example, Sweden was neither active in up- nor downloading, despite having a large, well-established forest-based sector, high forest cover, and a national forest policy that aligned well with the Forest Action Plan. The main explanation for this is that the plan simply did not have anything to contribute to the national forest policy, as noted earlier. In addition, since the plan is entirely voluntary, the States in this group chose not to engage in its implementation, or engaged only where they could benefit from either up- or downloading (e.g., reducing costs in developing the national policy).

6. Conclusions

Our analysis of the EU Forest Action Plan started with the assumption that the EU Member States would either engage in “pace-setting,” “foot-dragging,” or “fence-sitting,” depending on the perceived importance of the forest-based industry and each State’s respective forest cover (see

Table 1). At the EU level, the results confirm that the Forest Action Plan did indeed provide a point of reference and framework for forest-related deliberations. For example, several concrete outputs were produced (e.g., studies and SFC opinions) and the plan appears to have been useful in terms of coordination and information sharing between the Member States and the Commission, both in horizontal and vertical terms [

53]. However, there is limited evidence to suggest that the activities and attributed effects can be credited to the Forest Action Plan, as most activities in the plan were interlinked with pre-existing actions at either an EU or national level. Most activities appear to have been principally connected with the plan purely for reporting purposes. The lack of activities that can be directly attributable to the Forest Action Plan can be attributed to an absence of binding targets, varying commitments to action, and the lack of direct funding [

53]. It can be noted in this regard that similar results have been reported for the more recent Forest MAP [

38,

51]. More relevant for this paper, however, is that our analysis of the plan supports the general assumption that it generated different degrees of implementation and uptake across the EU Member States. It is also this variation across States that constitutes the main reason for re-visiting the Forest Action Plan rather than the more recent Forest MAP [

39,

40].

Despite the varied up- and downloading by Member States, the Forest Action Plan demonstrates that EU forest policymaking has had an impact at a national level, even though there is not a common forest policy, nor is the Forest Action Plan binding in any regard. In the end, the plan added value to the implementation of the EU Forestry Strategy by setting the topics for 2007–2011 on one agenda and by operationalizing the principles of the EU Forestry Strategy for a shared implementation by Member States. It is, nevertheless, clear that the impact varies from one State to another based on the goals defined on a national level, with some that were determined to comply with the plan, whereas in others, the plan’s activities and priorities had already been included in the national agenda well before it was defined. Furthermore, several Member States with a significant forested area have seemingly not been more influenced or active in its development or implementation. This also means that the degree of downloading is not dependent on forest cover or the importance of national forest-based industries, but, rather, the extent to which there was a forest policy vacuum—one that can be addressed by the Forest Action Plan and subsequently embraced by Member States. With this in mind, the degree of up- vs. downloading appears to be interlinked with the process of Europeanization or (by chance) it coincided with ongoing national processes where it provided a neutral and convenient download. It is, moreover, not a question of whether countries are highly industrialized or industrial latecomers (e.g., high and low levels of regulation), which is often defined as a criterion for up- and downloading. This background would explain the variations in how enthusiastically the plan was embraced by some Member States (downloading) vs. those Member States that pushed for the Forest Action Plan (uploading) during its formulation in 2005 and 2006.

It is also worth noting that, as the Forest Action Plan was a voluntary instrument, no Member State chose to implement activities that ran contrary to their own national interests or agendas. This was also to be expected from this type of policy instrument. However, the degree of downloading has been dependent on two factors: namely, ongoing national reviews of forest-related policy instruments (e.g., Germany was reviewing its forestry strategy at the time and utilized the Forest Action Plan as a basis for discussion) and the Europeanization of newly ascended countries (e.g., Member States establishing NFPs and playing catch up with regard to the European forest policy). In both cases, the Forest Action Plan provided a pre-existing structure and/or framework (e.g., as a reference point) that countries could easily download from the EU level.

These findings demonstrate that there are significant variations in the implementation of soft vs. legally binding instruments. While this may have been an expected result, no studies have, to date, looked at the implementation of soft policy instruments at a national level from a comparative perspective. This article contributes to closing this gap and adds to the implementation literature. However, and most importantly, the results demonstrate the need for a more nuanced and varied approach to the implementation of soft policy instruments. The additional implementation categories in

Table 2 (”Dual-driving,” “Catching-up,” “Front running,” and “Non-participating”) were put forward to reflect the need to give the theoretical frameworks used greater harmony with real-world outcomes and can be used to complement those put forward by Börzel [

12] for legally-binding instruments. In short, Member States exhibit varied strategies when implementing soft policy instruments, as their decision paradigms substantially differ. More specifically, the costs and benefits of complying are not the same when compared to a legally binding instrument. This also means that the motivation and objectives for up- or downloading are not the same. More studies are needed to review how the implementation and the decision-making involving soft policy instruments differ from those legal instruments, on which, considerable research has already been undertaken.