1. Introduction

Higher, more persistent, or more volatile inflation plays a significant role in fiscal sustainability [

1]. Fiscal deficit can be the significant cause of inflation, is one of the views of macroeconomics [

2]. Specifically, for developing countries, it is very challenging to control this single variable “inflation rate”. This has been a serious macroeconomic problem of attaining a steady growth in the economy. There are various factors that can cause inflation in the economy, and the fiscal deficit is one of them. A large fiscal deficit occurs when the government spending is high relative to government revenues. Fiscal deficit and inflation are both serious economic problems in developing countries, and inflation has attracted much attention from economists. However, less attention is given to fiscal deficit and its relationship with inflation. The transmission mechanism of fiscal deficit operates in two ways [

3]: (1) the government can reduce the fiscal deficit by raising tax, which leads to increased cost of production, so producers will increase prices in market for consumers, the result is cost-push inflation from the supply side; (2) the government can reduce fiscal deficit through printing of new money, in that way money supply will be increased in market, which in turn raises aggregate demand and prices, known as demand-pull inflation [

4]. The demand-pull inflation is based on well-known Fisher equation quantity theory of money, MV = Py, the direct relationship between money supply and price level [

5]. Fiscal deficit creates both sides of inflation (demand and supply).

Malaysia, as an emerging economy, has maintained a starring record of macroeconomic management, for instance, [

6]. The country needs a fiscal policy framework, which should be carefully designed to confirm that expenditures are consistent with social objectives and available for financing [

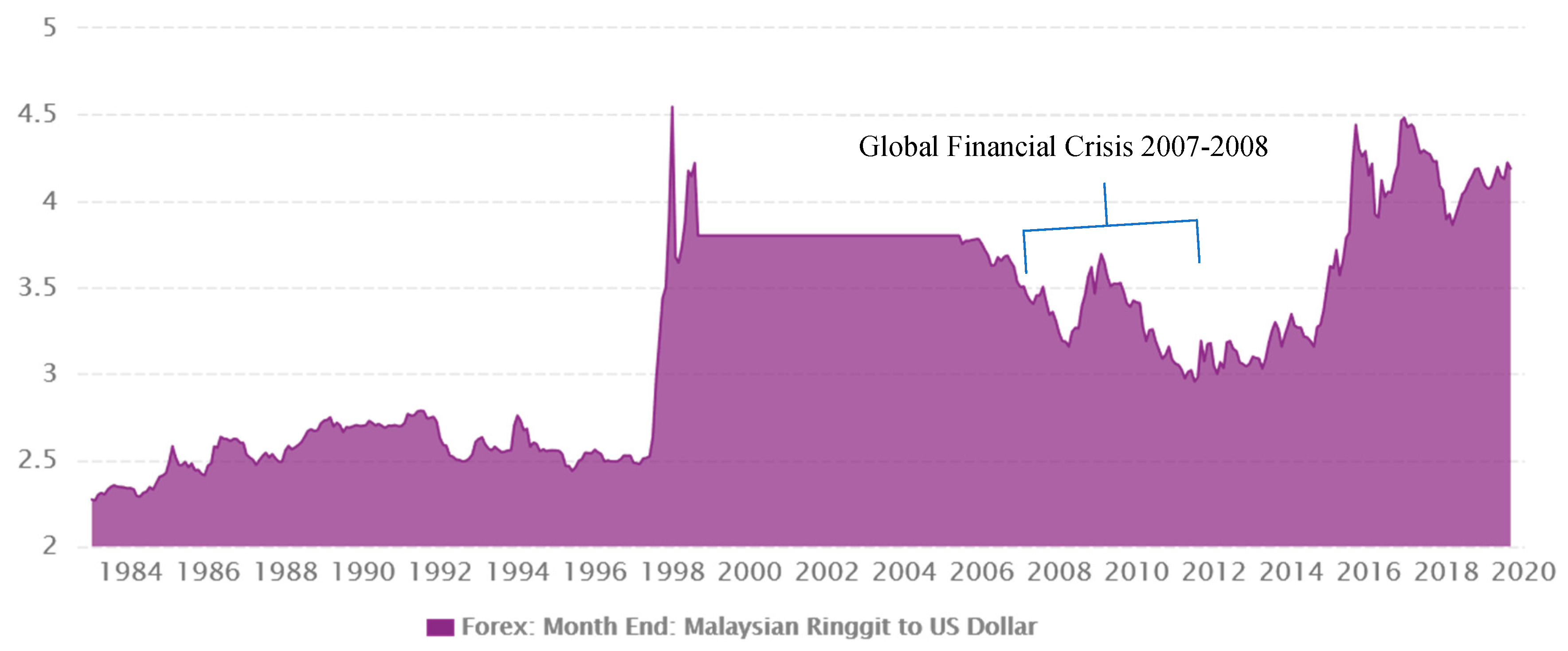

7]. In 1981–1986 crises, Malaysia has experienced a severe current account deficit. The budget deficit as a percentage of Gross National Product (GNP) was historically high, up to 18% in 1983. The public debt at Gross Domestic Product (GDP) percentage sharply increased from 44% in 1980 to 103.4% in 1987. In the late 1990s, Malaysia faced heavy selling pressure on ringgits because of the Thai Baht depreciation in May 1997. In January 1998, Ringgit depreciated against the dollar by almost 50%. However, the low foreign debt experience of financial institutions made Malaysia policymakers unable to manage the situation. In short, fiscal profligacy was the main reason of macroeconomic imbalance in the first two crises, that is, 1981–1986 and 1997–1998. The first two crisis happened in Malaysia somewhat based on fiscal grounds, and financing sources of fiscal deficits. Malaysia, affected by the Asian crisis 1997 and the Global crisis 2007–2008 (see,

Table 1, and

Figure 1), is planning to enrich the effectiveness of government expenditures through the application of zero-based budgeting, in which all expenditures will be justified for each new period, as reported in the annual report 2018 by Bank Negara [

8]. The overall balance of the Federal Government budget is 3.7 percent of GDP, as per the report of the Ministry of Finance [

9]. Fiscal deficit can be financed through many sources, for instance, printing of new money, domestic borrowing, and external borrowing. In Malaysia, domestic borrowing includes the Bank institution borrowing (commercial banks) and central bank borrowing, and these sources and more are highlighted by Bank Negara Annual reports. While in external borrowing, the most important are medium- and long-term borrowing and short-term borrowing. In past trends, Malaysia has faced a rising inflation of 5.44% and faced a fiscal deficit of 35,594 RM million (RM denotes the Malaysian currency symbol) in 2008 Q1 as per World Bank Data [

10]. As mentioned earlier, there are sources of financing the fiscal deficit, but debt levels always exert extra pressures on the fiscal sustainability of public finances [

11].

Consequently, to lessen this pressure and assuming fiscal sustainability as a constraint, it is essential to choose those sources which are less inflationary. There are several factors from supply side and demand side which can be responsible for inflation, like oil prices and food prices in the market. Now, the question is whether the fiscal deficit is inflationary in Malaysia? If it is inflationary, then which sources of financing the fiscal deficit are less inflationary? Ideally, at the time of fiscal deficit in the economy, the government covers the deficit with less inflationary sources. Sources with high inflation costs can make the economy in trouble. While discussing fiscal deficit and sources of financing and inflation, it is considered important to also discuss political instability in this study. As mentioned, political instability has been given less importance in studies, even though it causes many economic problems, and one of the critical economic problems is the inflation rate [

12]. Political instability (PS) refers to fluctuations or variabilities in the political system which severely damage the economic system of a country. In Malaysia, political stability has specific challenges, such as institutional reforms, job-led growth, religious and racial issues, and national security challenges. In this study, political instability (PS) is considered as a moderator between fiscal deficit and inflation. The index range of PS is −2.5 (refers

Not stable) to 2.5 (more

Stable).

In general, several studies argued about fiscal deficit and inflation [

3,

13,

14]. These arguments are based on theory, that is, Fiscal deficit causes an increase in money supply, inflation, which increases the interest rate and finally, crowds out the investment in the private sector. According to the Keynesian school of thought, budget deficit affects the interest rate, inflation through financing methods. Besides, the Monetarist school of thought argued that budget deficit affects money supply and inflation through financing methods. A plethora of studies has been done on the relationships of fiscal deficit and inflation [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].However, these studies have only analyzed the fiscal deficit and inflation as theoretically described in the fiscal theory of price, but another side of the fence has been ignored, which is the sources to finance the fiscal deficit and its inflation cost. It is essential to address the budget balance because, in the short run, it becomes crucial for the government to control inflation in the country [

20]. Also, political instability has a significant relationship with rising inflation, as reported by Barugahara [

21], Aisen & Veiga [

22], and Telatar et al. [

23]. As discussed earlier, the political instability means certain challenges in Malaysia, which is given less importance in the previous studies, even though it causes a high inflation rate [

20,

21]. So, it is quite important to know the impacts of fiscal deficit on inflation having political instability as a moderator. Further, from a technical perspective, the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) technique has been used in previous studies to find out the long-run relationships, but its sensitivities are missing, for example [

16,

24]. Thus, this study re-estimates the model by incorporating Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS), Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS), and Canonical Cointegration Regression (CCR) techniques to find out the robustness of the estimates.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between fiscal deficit and inflation in Malaysia’s economy, along with long-run and short-run relationships. The second objective is to evaluate the sources, including external and internal, to finance the deficit with less impact on inflation. Also, the third objective of this study is to examine the political instability as a moderating variable between inflation and fiscal deficit in Malaysia.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the findings of previous related studies,

Section 3 explains the data sources and methodology,

Section 4 presents the empirical findings,

Section 5 discusses the empirical findings, and finally,

Section 6 gives the concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between fiscal deficit and inflation with both time-series and panel data. Nguyen [

15] examined the impacts of fiscal deficit and money supply (M2) on inflation in nine Asian countries and concluded that M2 and fiscal deficit have a positive and significant impact on inflation. Lin and Chu [

16] applied dynamic quantile regression model under autoregressive distributive lag (ARDL) and investigated the fiscal deficit and inflation relationship in 91 countries from 1960–2006, empirical results showed that fiscal deficit could be inflationary when there is already inflation in the economy (high-inflation time) and can be less inflationary in low-inflation time. Sergey Pekarski [

17] examined shifts in moderate and hyperinflation occurring because of shifts in monetary and fiscal policy by considering Laffer curve—represents the relationship between the tax rate and the amount of tax collected by governments, which is used to illustrate the Laffer’s argument that sometimes cutting tax rate can increase total revenue [

25], and Olivera-Tanzi effect—an economic situation involving a period of high inflation and a decline in tax revenues, which can divide the budget deficit effect into two parts, one part, which is subject to negative inflation, and the second part, which is inflation proof. Graeve and Heideken [

18] discussed anticipated inflation, which is strictly related to fiscal policy, and pointed out that warnings for fiscal inflation are always ignored in policies. The results suggested that fiscal inflation had already induced a 1.6 percent points increase in long-term inflation in 2001. Nandi [

26] investigated the monetary policy and fiscal policy consistency and found that under high interest rate, passive monetary policy is consistent with fiscal policy. The study findings suggested the impact of fiscal policy on monetary policy; for instance, favorable fiscal policy can make monetary policy expansionary. The study highlighted the issue that there is a need for coordination between both policies. Ahmad and Aworinde [

19] analyzed the relationship between fiscal deficit and inflation in twelve African countries using quarterly data by using asymmetric cointegration analysis, which is suitable for African countries with under-developed and imperfect financial markets system. The study exposed that fiscal deficit is inflationary in Africa, and there is a long-run relationship between fiscal deficits and inflation, indicating the importance of fiscal consolidation. Montes and Limba [

27] analyzed fiscal transparency and its effects on inflation, inflation expectations, inflation volatility, and inflation expectations volatility in 82 developed and developing countries. Their findings suggested that countries could have low inflation volatility and low inflation expectations volatility as well as lower inflation and lower inflation expectations with a high level of fiscal transparency; especially in developing countries, fiscal transparency has a substantial impact on inflation. Hove et al. [

28] studied the importance of institutional quality regarding the inflation target regime in emerging market economies. The study found that monetary policy is more effective in countries having good institutions. Canh [

29] examined the effects of fiscal policy on economic growth under the contributions of internal and external debt levels in emerging market economies. The findings showed the fact that improvements in institutions can promote a huge crowd in the effects of fiscal policy and reported nonlinear effects of external debt on economic growth. Jalil et al. [

30] tested the fiscal theory of price level in Pakistan covering the period from 1972 to 2012. The study exposed the fact that fiscal deficit is a significant contributor to inflation, along with other factors like interest rate, government sector borrowing, and private borrowing. Asterio [

31] examined large fiscal deficits and public debt (by considering fiscal and budgetary shocks) and developed a macroeconometric model for the Greek economy. They have reported that the Greek government should try to reform fiscal programs which can boost the Greek economy. A similar study [

32] investigated the impact of economic growth and external debt on fiscal deficit in Jordan, after using unit root and ARDL bound test, the empirical results showed that external debt has a negative impact on the budget deficit in Jordan. A related study reported the effects of a fiscal deficit on inflation in selected African Countries [

33]. It concluded that in Nigeria, inflation is affected positively by the fiscal deficit in the short run and long run, while in South Africa and Kenya; there is a short run and adverse effects.

The review of studies shows that many studies have analyzed the relationship between fiscal deficit and inflation. However, the literature is lacking in the subject domain and shows a clear gap to fulfill. This study is considering domestic sources and external sources to finance the fiscal budget. The domestic sources include central bank and bank institutes, while the external sources include medium- and long-term loans and short-term loans. This study analyzes each of these sources of financing for fiscal budget and their corresponding inflation cost so that the policymakers can target the specific less inflationary sources to covers up the fiscal deficit.

5. Discussion

Numerous studies have reported the relationship between inflation and fiscal deficit and concluded different findings [

16,

19,

29,

30]. Theoretically, the fiscal deficit is inflationary, but the impact and significance of its source of financing on inflation are varied. The analysis of this study is carried out in three stages of estimation. In the first-stage estimation, the model in Equation (4) is used; in the second-stage estimation, the model in Equation (5) is used; and in the final third-stage estimation, the model in Equation (6) is tested. In the first model, which can be called in general a model, inflation is depending on the overall fiscal deficit, money supply, and the GDP. Through the ARDL bound test, it is confirmed that there is a long-run relationship between inflation and fiscal deficit. While analyzing the short-run estimation, there is also a short-run relationship between inflation and fiscal deficit, but it is significant at 6%. In this study, after finding the short-run and the long-run relationship, the sensitivity of parameters is also estimated by using ARDL, FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR techniques. The coefficient of fiscal deficit is 5.75 in ARDL, 1.09 in FMOLS, 1.01 in DOLS, and 1.04 in CCR findings. All coefficients are positive, as expected, and significant at 1% and 5%. Increasing fiscal deficit implies an increase in inflation. Malaysia’s economy is facing a fiscal deficit, and then obviously, the government must face its inflation cost as well. In the same model, the money supply has shown a significant impact on inflation. Due to the fiscal deficit, a country may print new money, which can create inflation. As Lin and Chu [

16] discussed, if inflation is already high, then the fiscal deficit may produce more inflation, but on the other hand, the fiscal deficit can be less inflationary in a steady inflation period.

In the second stage of estimation, the fiscal deficit is replaced by two main sources of financing, that is, the external source of borrowing and domestic source of borrowing, along with political instability as a moderator. The political instability is not included in the first stage of estimation because in the first stage, the aim is to find out the overall impact of fiscal deficit on inflation, GDP, and Money supply. In the second stage, it can be explicitly observed how the political instability moderates the relationship between the sources of financing and inflation, see

Table 7. Hence, according to the findings, there is a long-run relationship between the sources of financing and inflation. In the short-run analysis, the external sources of borrowing have also shown a short-run relationship with inflation, when the government borrows money from the external sources to cover up the fiscal deficit, affecting the money supply in the country’s economy and causing inflation in the short run. On the other hand, domestic borrowing has a long-run relationship, if the government takes domestic borrowing, which may not be in a large amount and may not be affecting in the short run, but in the long-run, it is significantly inflationary, see

Table 8. Political instability is also one of the critical factors which can affect inflation. Recently, the Malaysian government has changed through their democratic process, resulting in changes in the revenue structure and the regulations, which affected the price level in the market.

In the third stage of estimation, the external sources, including short-, medium-, and long-term borrowing, are having a short-run relationship with inflation. The short-term borrowing can be helpful for the government to support the fiscal deficit because the short-term borrowing is less-inflationary relative to medium- and long-term borrowing. In the long-term analysis, it is very clear from the findings that the central bank borrowing and the Bank institution borrowing have a less and significant impact on inflation. Utilization of these funds must be productive when the government funds fail to achieve development policy over the long term, and it can seriously damage the fiscal stability [

61]. On the other hand, the government is relying on medium- and long-term borrowing and short-term borrowing to achieve the gap in the fiscal deficit, which is inflationary. In specific analysis (after dividing the external and domestic sources), political instability is not significantly affecting the market price levels.