Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Tourism in Selected Cities in Turkey and Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- be easy to identify and measure,

- be significant for the functioning of the ecosystem,

- have a high cultural, socio-political or economic value,

- be sensitive to the measured changes and describe understandable mechanisms,

- respond to changes quickly and be unambiguous.

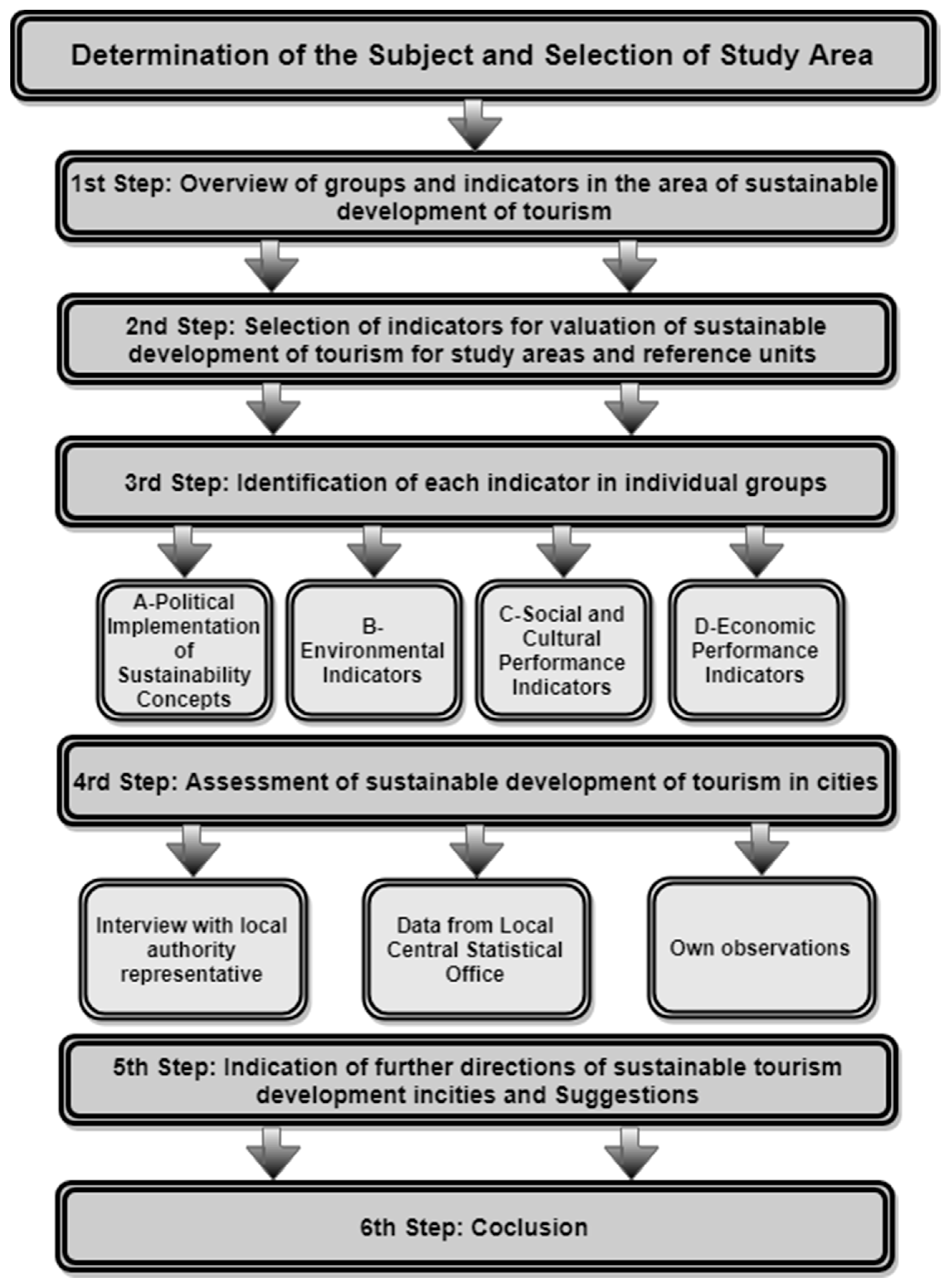

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Basic indicators that may be used to all tourist destinations and

- (2)

- Specific (supplementary) indicators used only in specific types of areas.

- Indicators that are specific for all ecosystems used for each type of ecosystem, e.g., wetlands, beaches, mountainous areas, cities, islands, etc.

- Indicators that are specific for each given locations they should be determined for each destination on an individual basis.

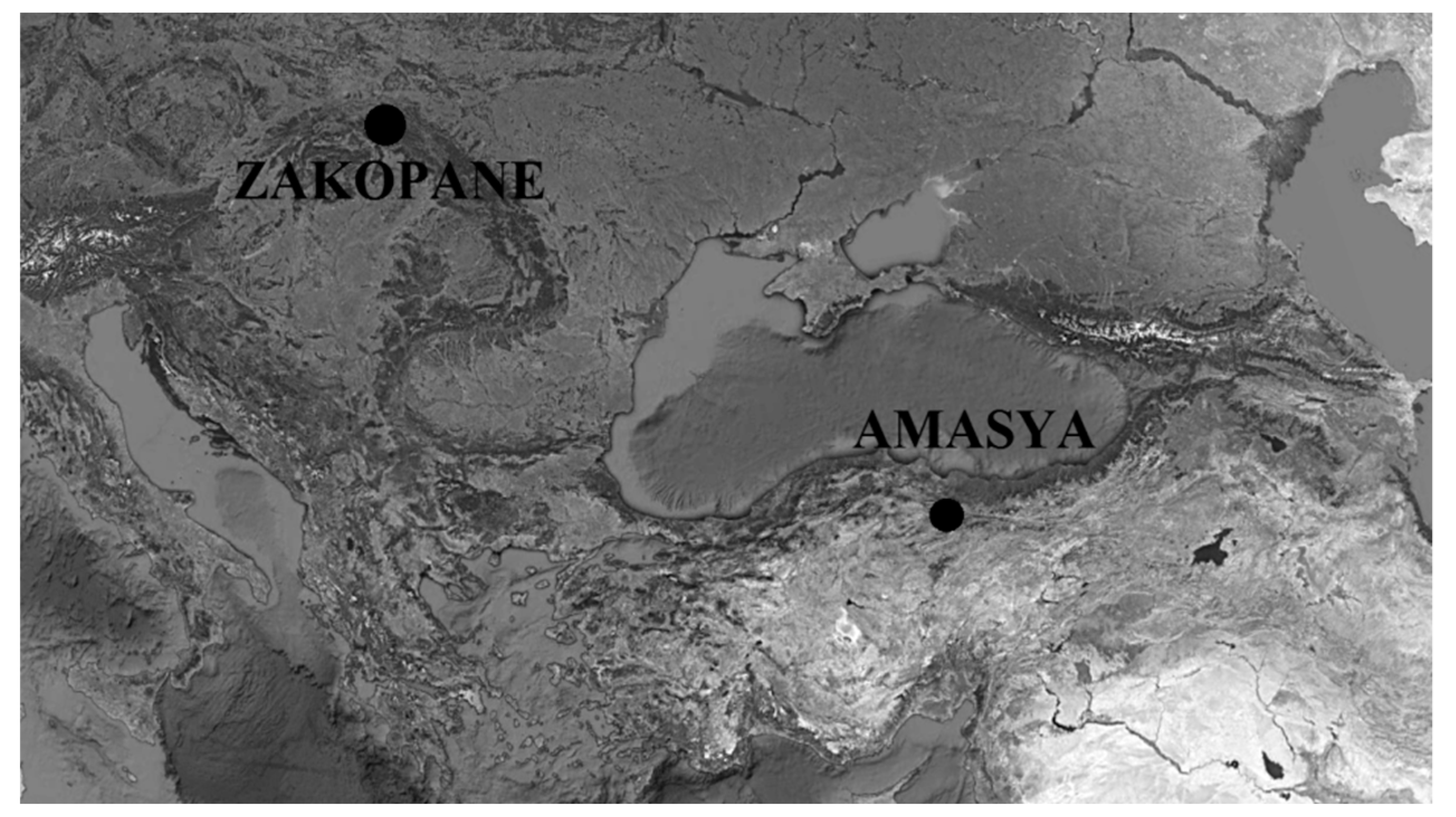

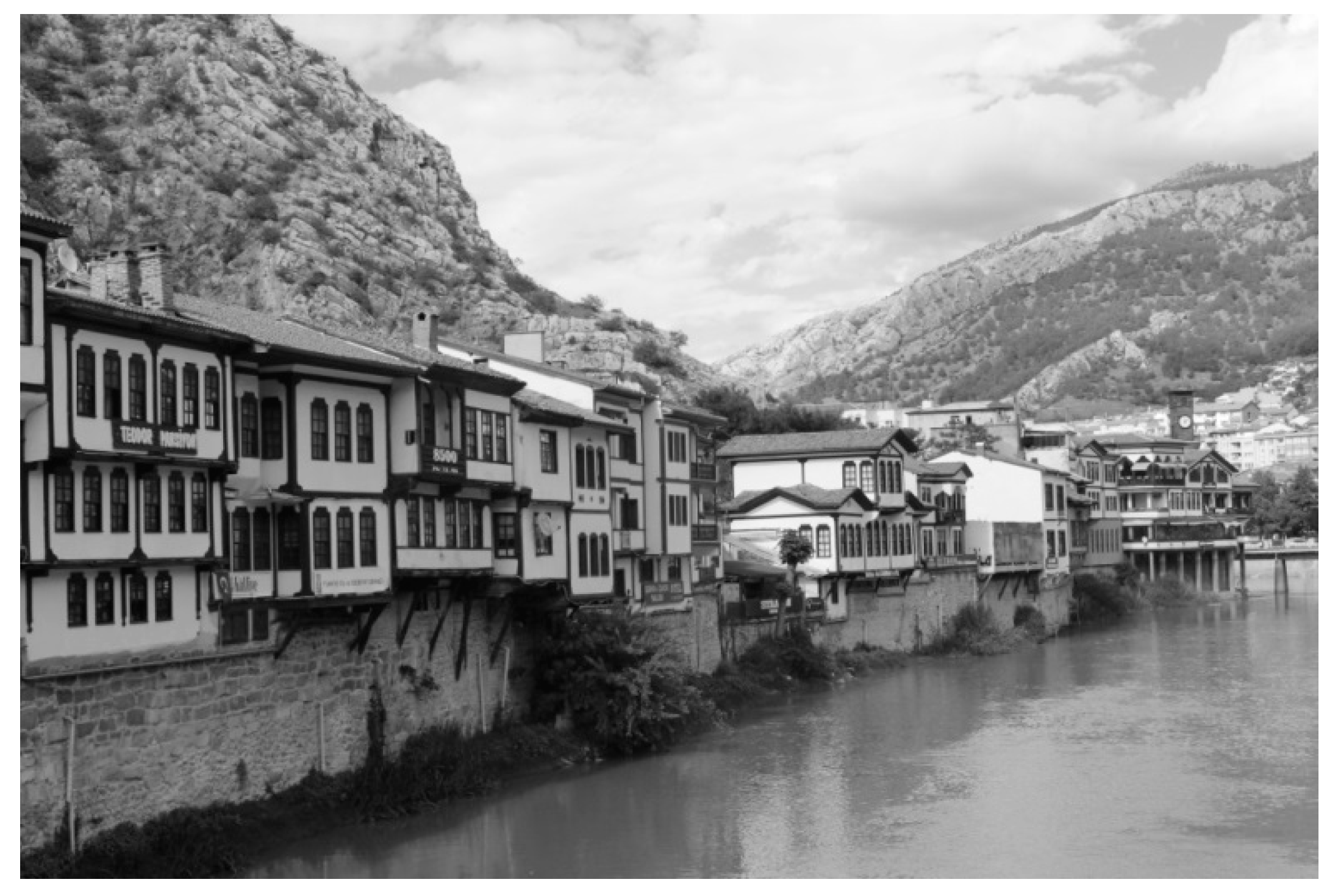

General Characteristic of the Cities

3. Results

- Policies of local and supra-local authorities

- Environmental

- Social and cultural

- Economic

4. Conclusions

- Amasya city does not have enough number of accommodation beds and hotels, so the accommodation fee is high.

- Contrary to Zakopane, the diversity of facilities related to tourism in Amasya is limited.

- Due to the natural values that it has, it is seen that mostly cultural tourism is done in Amasya and winter tourism is done in Zakopane.

- Both cities have thermal water resources and use renewable energy sources. While thermal energy is used in Zakopane, solar power is used in Amasya.

- The assessment of sustainable tourism development in both locations revealed a significantly lower environmental impact (less environmental stress) in the location of Amasya. It is manifested, e.g., by a smaller number of residents as well as the total number of residents and tourists per 1 km2.

- Concerns are also raised by a significant share of people employed on a temporary basis in Zakopane. It often eliminates permanent residents from the job market. The structure of employment in Amasya presents a different structure as it is closer to the model of sustainable development.

- The local authorities are striving for a “pro-ecological” policy, manifested in e.g., the method of receiving domestic sewage and the share of buildings connected to the sanitary sewage system.

- Indicated further actions may contribute to the development of sustainable cities. This is the last moment for Zakopane, especially in terms of improving air cleanliness and spatial order.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kowalczyk, M. Tourism Sustainable Development Index. Człowiek Środowisko 2011, 35, 35–50. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wheller, B. Sustaining the Ego. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse e Towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B. Tourism function and sustainable development of the seaside areas on the example of west pomeranian voivodeship’s communes. In Gospodarka Turystyczna w Regionie. Wybrane Problemy Funkcjonowania Regionów, Gmin i Przedsiębiorstw Turystycznych Red; Rapacz, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2013; Volume 303, pp. 170–178. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B. Nowe Trendy W Kreowaniu Produktów Turystycznych. Acta Sci. Pol. Oecon. 2010, 9, 313–322. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The competitive destination: A sustainable perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Managementm; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Tourism management. Available online: https://books.google.pl/books?hl=pl&lr=&id=1WQtIOqVT3gC&oi=fnd&pg=PP8&ots=GVQ129CRkJ&sig=tgolbJ7maqAzUVBCG-yFeu1YTRA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The elusiveness of sustainability in tourism: The culture-ideology of consumerism and its implications. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable Tourism: A state-of-the art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; CABI: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulic, J.; Kozic, I.; Kresic, D. Weighting indicators of tourism sustainability: A critical note. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 48, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry. WTO. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/search/?q=au%3a%22World+Travel+and+Tourism+Council%22 (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Hełdak, M.; Raszka, B. Evaluation of the Local Spatial Policy in Poland with Regard to Sustainable Development. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 22, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Methodological Work on Measuring the Sustainable Development of Tourism—Part 2: Manual on Sustainable Development Indicators in Tourism; Office for Official Publications on the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Environmental Agency—EEA. European Briefings—Tourism. Available online: http://www.eea.europa.eu/soer-2015/europe/tourism (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Alberti, M. Measuring Urban Sustainability. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1996, 16, 381–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, A. Measuring up to sustainability. Futures 1998, 30, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkisson, A. Developing Indicators of Sustainable Community: Lessons from Sustainable Seattle. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1996, 16, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P.; Spurr, R. Evaluating tourism’s economic effects: New and old approaches. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, R.S.; Teivane, U. Resident perceptions of tourism development in Riga, Latvia. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hełdak, M.; Raszka, B. Prognosis of the Natural Environment Transformations Resulting from Spatial Planning Solutions. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 20, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M. Borough Development Dependent on Agricultural, Tourism, and Economy Levels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdoğlu, B.C.; Kurt, S.S. Determination of Greenway Routes Using Network Analysis in Amasya, Turkey. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2017, 143, 05016013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdoğlu, B.C.; Kurt, S.S.; Celik, K.T.; Ustün Topal, T. Greenway Planning Process in the Example of Toklu Valley. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2016, 17, 611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, S.S.; Düzgüneş, E.; Kurdoğlu, B.C.; Demirel, Ö. Example Study About Meryemana Valley (Trabzon/Turkey) for Determining the Potential Campground in the Scope of Nature Tourism. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2016, 17, 576–583. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (WTO). Indicators of sustainable development in tourism destination. In A Guidebook; WTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulou-Georgudaki, J.; Kalogeras, A.; Konstantinopoulos, P.; Theodoropoulos, C. Sustainable tourism management and development of a Greek coastal municipality. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIDA (Canadian International Development Agency). Indicators for Sustainability: How Cities Are Monitoring and Evaluating Their Success. 2012. Available online: http://sustainablecities.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/indicators-for-sustainability-intl-case-studies-final.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- European Commission. European Tourism Indicator System TOOLKIT for Sustainable Destinations. 2013. Available online: https://www.surrey.ac.uk/shtm/Files/ETIS%20TOOLKIT.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Hickey, G.M.; Innes, J.L. Indicators for demonstrating sustainable forest management in British Columbia, Canada: An international review. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasser, E.; Sternbach, E.; Tappeiner, U. Biodiversity indicators for sustainability monitoring at municipality level: An example of implementation in an alpine region. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahin, R.; Veleva, V.; Hart, M. Do Indicators Help Create Sustainable Communities? Local Environ. 2003, 8, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J. An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 59, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VISIT (Voluntary Initiative for Sustainability in Tourism) Initiative. Tourism Eco-Labelling in Europe—Moving the Market Towards Sustainability. 2004. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/life/project/Projects/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.showFile&rep=file&fil=LIFE00_ENV_NL_000810_LAYMAN.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Central Statistical Office. Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Caalders, J. Managing the transition from agriculture to tourism: Analysis of tourism networks in Auvergne. Manag. Leis. 1997, 2, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Cutumisu, N. Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy in WWF Pan Parks: Case of a Swedish and Romanian National Park. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P. Trends in Park Tourism: Economics, Finance and Management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welford, R.; Ytterhus, B. Sustainable development and tourism destination management: A case study of the Lillehammer region, Norway. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2004, 11, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; White, V.; McCrum, G.; Scott, A.; Hunter, C. Measuring responsibility: An appraisal of a Scottish National Park’s sustainable tourism indicators. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Simanic, B.; Martinac, I.V.O. Environmental training and measures at scandic hotels, Sweden. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 9, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B.; McCabe, S.; Mosedale, J.; Scarles, C. Research perspectives on responsible tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, L.; Cabanban, A.S. Planning for sustainable tourism in southern pulau Banggi: An assessment of biophysical conditions and their implications for future tourism development. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuppen, H. Water Management and Responsibility in Hotels. Green Hotelier, 2013. Available online: http://www.greenhotelier.org/know-how-guides/water-management-and-responsibility-in-hotels/ (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Perrings, C.; Ansuategi, A. Sustainability, growth and development. J. Econ. Stud. 2000, 27, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A. Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Indicator Name | Unit | Data Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | Poland | |||

| A | Political implementation of sustainability concepts | |||

| A-1 | Existence of a local policy for enhancing sustainability in the destination: Existence of a political strategy decision or an action plan | Yes/No | Interview with local authority representative | Interview with local authority representative |

| A-2 | Involvement of stakeholders: Are there stakeholders continuously involved in designing, revising and monitoring the sustainability strategy | Yes/No | Interview with local authority representative | Interview with local authority representative |

| A-3 | Existence of an inventory of sites of cultural interest: e.g., monuments, buildings, UNESCO heritage sites | Yes/No | Tourist information | Tourist information |

| A-4 | Existence of an inventory of sites of natural interest: e.g., protected areas, habitats, especially vulnerable areas, Natura 2000 | Yes/No | Tourist information | Tourist information |

| A-5 | Number of eco-labelled tourism facilities or facilities applying for environmental management schemes (such as EMAS or ISO 14000): Including hotels, restaurants, camping sites or other tourism services | Pcs. | Tourist information | Tourist information |

| B | Environmental Indicators | |||

| B1 | Tourism transport (access to destination and return travel, local mobility) | |||

| B1-1 | Daily number of guests per 1 km2 | no. of tourists per 1 km² | Own observations | Tourist information, GUS-BDL |

| B1-2 | Local mobility: types of means of transport | Pcs. | Own observations | Own observations |

| B2 | Carrying capacity—land use, bio-diversity, tourism activities | |||

| B2-1 | Maximum population density (peak season) per km² | per 1 km² | TUIK | GUS—BDL and own observations |

| B2-2 | Beds in secondary residences (in % of total lodging capacity) | % | TUIK | GUS—BDL and own observations |

| B2-3 | Ratio of built-up area to natural areas | 1:1 | TUIK | GUS—BDL |

| B2-4 | Size of protected natural areas (in % of total destination area) | % | TUIK | GUS—BDL |

| B2-5 | Evolution of different leisure time activities with intensive use of resources: Evolution of different leisure time activities with intensive use of resources:

| Pcs. km2 | own observations | own observations |

| B.3 | Use of energy | |||

| B3-1 | Percentage of renewable energy in total energy consumption (entire destination, locally produced or imported): Ratio of energy consumption per year covered by renewable resources. | 1:1 | Policy of local authorities and TUIK | Policy of local authorities |

| B3-2 | Energy use by type of tourism facility | MW | Policy of local authorities | Policy of local authorities |

| B.4 | Use of water | |||

| B4-1 | Sustainable use of water resource | Ratio of water imported (pipelines, ships etc.) | TUIK | GUS—BDL |

| B4-2 | Percentage of houses and facilities connected to waste water treatment plants | % | TUIK | GUS-BDL |

| B.5 | Solid waste management | |||

| B5-1 | Percentage of solid waste separated for recycling | % | TUIK | GUS-BDL |

| B5-2 | Total of solid waste land-filled and/or incinerated | Tons/year | TUIK | GUS-BDL |

| B5-3 | Monthly table of waste production | Tons/month | TUIK | GUS-BDL |

| C. | Social and cultural performance indicators | |||

| C-1 | Percentage of non-resident employees in total number of tourism employees: seasonal percentage of non-resident employees in total number of tourism employees | % | TUIK and Tourist information | GUS-BDL |

| C-2 | Average length of contracts of tourism personnel: average length of contracts of tourism personnel | Months | Own observation | Own observations |

| C-3 | Percentage of land owned by non-residents | % | Own observation | Own observations |

| C-4 | Number of recorded thefts | No. | TUIK | GUS-BDL |

| C-5 | Tourist/host population ratio | 1:1 | TUIK and Tourist information | Own observations, GUS-BDL |

| D. | Economic performance indicators | |||

| D-1 | Seasonal variation of tourism-related employment | 1:1 | own observation | own observations |

| D-2 | Seasonal variation of occupation of the accommodation (beds) | 1:1 | own observations and Tourist information | Own observations |

| D-3 | Volume of accommodation (beds) per 1 resident | Number of beds (reported/number of residents | own observations and TUIK | Own observations, GUS-BDL |

| D-4 | Average duration of stay | Days | Own observations | Own observations |

| No. | Selected Historical and Cultural Features | Amasya (Turkey) | Zakopane (Poland) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. | Type of resort | Tourist resort, city | tourist resort, city |

| 2. | Location | At the foot of Harşena Mountains, in Turkey. Tokat from east, Tokat and Yozgat from the south, Çorum from the west and Samsun from the north. 334 km from Ankara, the capital city of Turkey | At the foot of the Tatra, in the Carpathian Mountains, in under the Zakopane Basin, (Kotlina Zakopiańska) 100 km from Cracow, the capital of Little Poland |

| 3. | Name of the region | Middle Black Sea | Podhale |

| 4. | Number of inhabitants (registered for permanent residence) | 326,351 (status for Dec 2016) | 26,737 (status for Dec. 2016) |

| 5. | Using the lodging (number of registered people) total | 93,689 | 3,200,000 |

| 6. | Population background | Local population started to increase in the 14th century when it joined the Ottoman state. Also, the population of the city is composed of Muslims and non-Muslims. | Pastoral nationals from Wallachia, wandering by the arc of the Carpathian Mountains, at the turn of the 14th and 15th century, assimilated with local population; the city also grew because of incoming population from other regions of Poland. |

| 7. | National minorities | None | None |

| 8. | Dialects | Turkish dialect | Podhale dialect |

| 9. | First settlement information | It is the oldest settlement in Anatolia. Settlement started in B.C. 4000. It continued Hittite, Phrygian, Kimmer, Scythian, Lydia, Persian, Hellen, Pontus, Roman, Byzantine, Danishmend, Seljuk, Ilkhanid and Ottoman periods. It was confirmed by Yıldırım Bayezid in 1393. The name Amasya is given by Strabon, who is known as the first geographer of the world. | Settlement privilege granted in 1578 (missing), confirmed by King Michał Wiśniowiecki in 1670. |

| 10. | Settlement origins | 16th century; in 1520, a city with 5681 inhabitants (together Muslim and non-Muslims) | 16th century; in 1676, a village with 43 inhabitants (together with Olcza and Poronin). |

| 11. | Formed architecture style | Ottoman style | Zakopane style |

| 12. | Beginnings of tourism movement development | Towards the end of the 20th century | Second half of the 19th century |

| 13. | Significant tourist and sport events | - | World championship in classical skiing in years 1929, 1939, 1962. |

| 14. | Cyclic events | International Festival of Atatürk, Culture and Art (12–22 June); series of cultural events: concerts, cherry competition, folk dance show, sport events, photo competition International Traditional Archey Festival (20–22 June); series of cultural events: concerts, sport events Festival of Plateau (18–26 July) | Annual World Cup in ski jumping during Wielka Krokiew (Big Rafter) International Festival of Mountain Folklore; series of cultural events: concerts, festivals, sport events, chess tournaments |

| 15. | Sport and tourist facilities | Visiting museums and historical sites, riding a bicycle/phaeton, trekking and hiking routes, camping, visiting spas, swimming pools, sports facilities | Cable railway—Kasprowy Wierch, numerous chair railways and ski lifts, ski-jumping take-off “Wielka Krokiew”, running tracks, aqua park, other swimming pools, halls and sports grounds, tennis courts |

| 15. | Social participation in city development | High social activity | High social activity |

| 16. | Inhabitants identification with “little homeland” | Significant | Significant, strong attachment to land |

| 17. | Regional products | Amasya apple, Toyga soup, blah, stuffed broad bean, Amasya bun | Podhale sheep cheese “bryndza” and “oscypek”—registered in the European Union as regional products |

| 18. | Return to “roots” | Significant, regional groups, folk bands, traditional handicrafts | Significant, regional groups, folk bands, cultivating traditional folk crafts, painting, sculpture and handicraft. |

| 19. | “Highlander style" of living philosophy | Important, also passed on from generation to generation without distortion | Matters greatly, Polish highlander language also gives a specific sense of freedom. śleboda, hyrność and honorność—transferred from generation to generation |

| 20. | Economic activity of the inhabitants | Medium (686 business entities) | High (over 5100 business entities) |

| Item | Indicator Name | Unit | Data Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amasya (Turkey) | Zakopane (Poland) | |||

| A | Political implementation of sustainability concepts | |||

| A-1 | Existence of a local policy for enhancing sustainability in the destination | Yes/No | Yes | Yes |

| A-2 | Involvement of stakeholders: Are there stakeholders continuously involved in designing, revising, and monitoring the sustainability strategy | Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No—dominant representation of local authority members |

| A-3 | Existence of an inventory of sites of cultural interest: e.g., monuments, buildings, UNESCO heritage sites | Yes/No | Yes | Yes |

| A-4 | Existence of an inventory of sites of natural interest: e.g., protected areas, habitats, especially vulnerable areas, Natura 2000 | Yes/No | Yes | Yes |

| A-5 | Number of eco-labelled tourism facilities or facilities applying for environmental management schemes | Pcs. | - | 15 |

| Item | Indicator Name | Unit | Data Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amasya (Turkey) | Zakopane (Poland) | |||

| B1. | Tourism transport (access to destination and return travel, local mobility) | |||

| B1-1 | Daily number of visitors per 1 km2 | No. of tourists per 1 km² | 85 | 97 |

| B1-2 | Local mobility: types of means of transport | Pcs. | 3 | 3 |

| B2. | Carrying capacity land use, bio-diversity, tourism activities | |||

| B2-1 | Maximum population density (peak season) per km² | Per 1 km² | 57 | 363 |

| B2-2 | Total accommodation (beds)—modified | Pcs. | 2572 | 3950 |

| B2-3 | Ratio of built-up area to natural areas | 1:1 | 0.23:1 | 0.15:1 |

| B2-4 | Size of protected natural areas (in % of total destination area) | % | 25.9% | 100% |

| B2-5 | Evolution of different leisure time activities with intensive use of resources, Evolution of different leisure time activities with intensive use of resources. | Pcs. | There are no lifts, or cable cars. Slopes are not covered with artificial snow. The city has 1 canoeing in river. It has about 7 km walking and bicycle routes along the river. There are hiking and trekking routes, camping areas around Borabay Lake. It has thermal water resources. | 7 skiing stations with cable cars, and ski lifts—most of the slopes are covered with artificial snow. Total length of skiing routes is approx. 16,400 m; Aqua park with thermal waters |

| B.3 | Use of energy | |||

| B3-1 | Percentage of renewable energy in total energy consumption (entire destination, locally produced or imported) | % | 22.82% | 6.8% (total consumption 200,6MW) |

| B3-2 | Energy use by type of tourism facility and per tourist | MW | N/A | 51.8 |

| B.4 | Use of water | |||

| B4-1 | Sustainable use of water resource | Ratio of water imported (pipelines, ships etc.) | 1:1 (128.56 hm2/year) | 1:1 (2523.4 dm3/year) |

| B4-2 | Percentage of houses and facilities connected to waste water treatment plants | % | 99% | 65.2% |

| B.5 | Solid waste management | |||

| B5-1 | Percentage of solid waste separated for recycling | % | 52% | 96.72% |

| B5-2 | Total of solid waste land-filled and/or incinerated | tonnes/year | 25.844 thousand tonnes 25,844.00 | 6.1 thousand tonnes 6100.00 |

| B5-3 | Monthly table of waste production | tonnes/month | 4.778 thousand tonnes 4778.00 | 0.5083 thousand tonnes 508.30 |

| Item | Indicator Name | Unit | Data Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amasya (Turkey) | Zakopane (Poland) | |||

| C. | Social and cultural performance indicators | |||

| C-1 | Percentage of non-resident employees in total number of tourism employees: seasonal percentage of non-resident employees in total number of tourism employees | % seasonal percentage of non-resident employees in total number of tourism employees | 1% | 20%–30% |

| C-2 | Average length of contracts of tourism personnel: average length of contracts of tourism personnel | month | 5 months | 2 months |

| C-3 | Percentage of land owned by non-residents | % | 3% | 8% |

| C-4 | Number of recorded thefts | No. | 660 persons | 250 persons |

| C-5 | Tourist/host population ratio | 1:1 | 5181:1 | 38:1 |

| D. | Economic performance indicators | |||

| D-1 | Share of tourism in the total target GDP | 1:1 | 2,740,410,900 TL | N/A |

| D-2 | Employment in the tourism sector in the peak of the season/out of season in comparison to total employment in the area | 1:1 | N/A | 0.4:1 0.6:1 |

| D-3 | Seasonal variation of accommodation occupancy | % | N/A | N/A |

| D-4 | Total accommodation capacity per capita of resident population | Number of (registered) accommodation beds/number of residents | 0.007 | 0.144 |

| D-5 | Average length of stay | Days | 1.6 days | 3 days |

| Item | Spheres of Action (Issues) | Further Directions of Sustainable Development of Tourism | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amasya | Zakopane | ||

| A | Political of local and supra-local authorities |

|

|

| B | Environmental |

|

|

| C | Social and cultural |

|

|

| D | Economic |

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurt Konakoglu, S.S.; Hełdak, M.; Kurdoglu, B.C.; Wysmułek, J. Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Tourism in Selected Cities in Turkey and Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092552

Kurt Konakoglu SS, Hełdak M, Kurdoglu BC, Wysmułek J. Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Tourism in Selected Cities in Turkey and Poland. Sustainability. 2019; 11(9):2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092552

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurt Konakoglu, Sultan Sevinc, Maria Hełdak, Banu Cicek Kurdoglu, and Joanna Wysmułek. 2019. "Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Tourism in Selected Cities in Turkey and Poland" Sustainability 11, no. 9: 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092552

APA StyleKurt Konakoglu, S. S., Hełdak, M., Kurdoglu, B. C., & Wysmułek, J. (2019). Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Tourism in Selected Cities in Turkey and Poland. Sustainability, 11(9), 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092552