Factors Affecting Chinese Young Adults’ Acceptance of Connected Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. What is Connected Health?

2.2. Potential Factors Affecting Connected Health Acceptance

2.2.1. Technology Factors

2.2.2. Individual Factors

2.2.3. Environmental Factors

3. Further Development of the Factor List

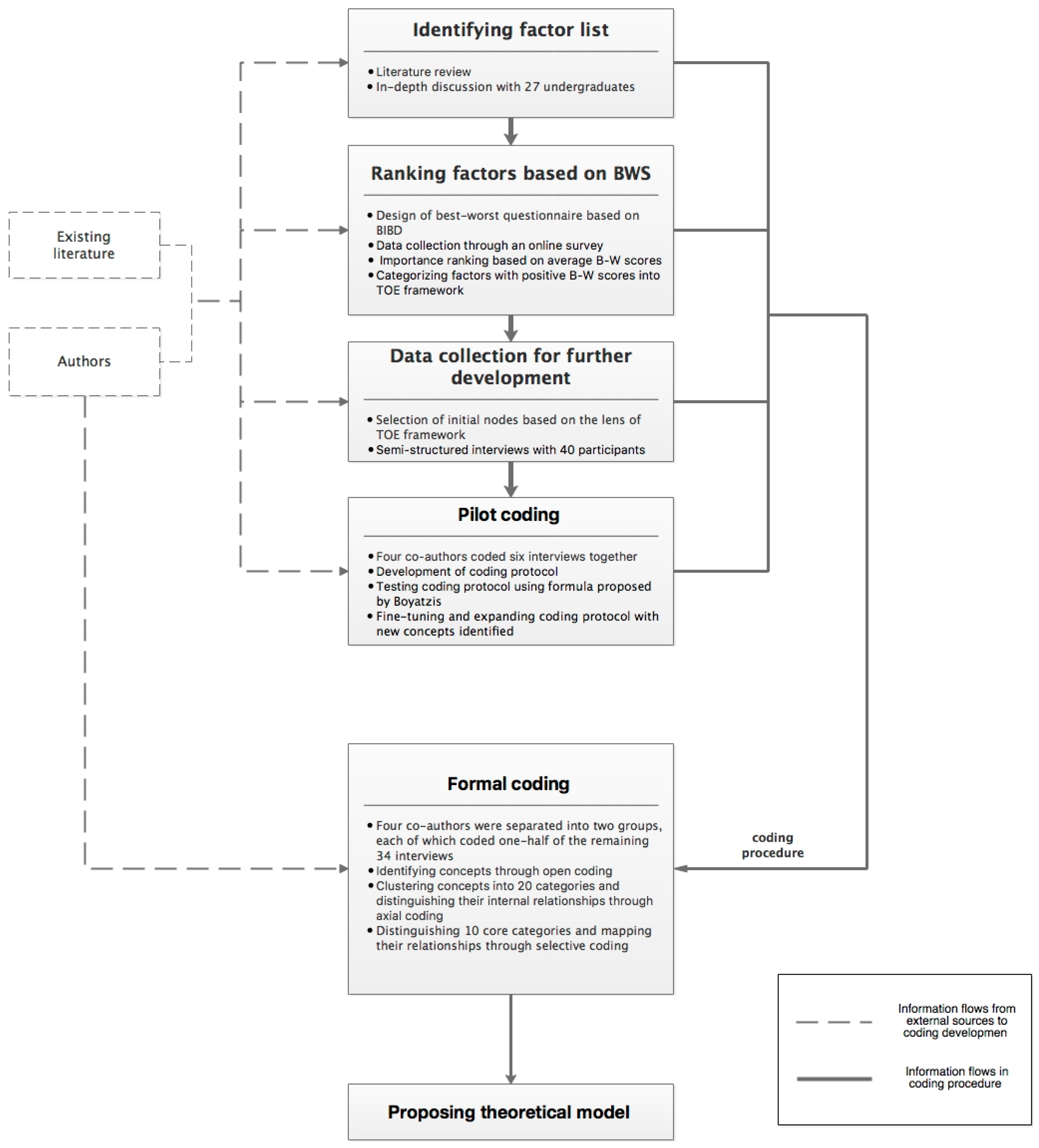

4. Methodology

4.1. Best–Worst Scaling Method

4.2. Design of Best–Worst Questionnaire

4.3. Sample and Data Collection

5. Data Analysis

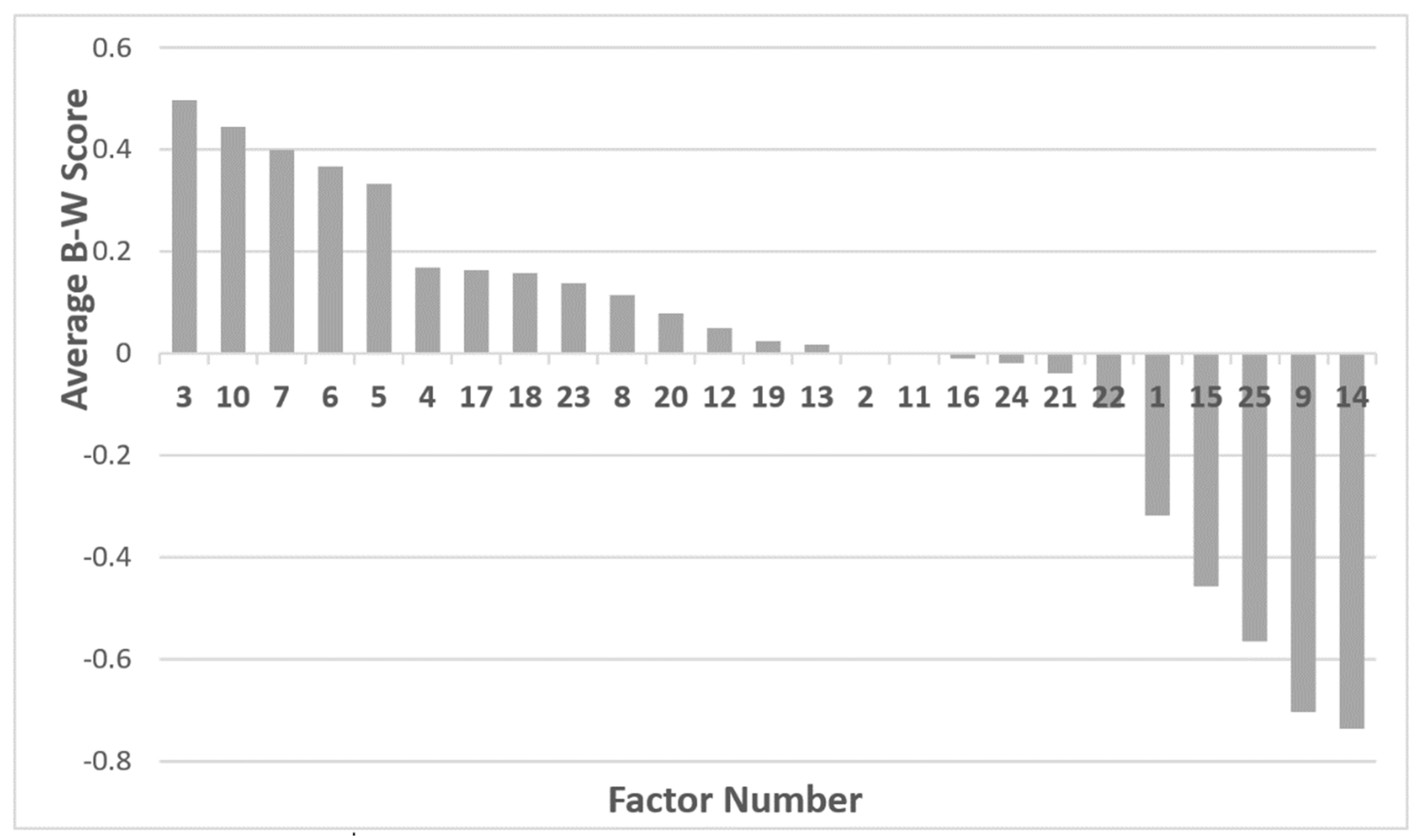

5.1. Absolute Importance of 25 Factors

5.2. TOE Framework of Factors Affecting Connected Health Acceptance

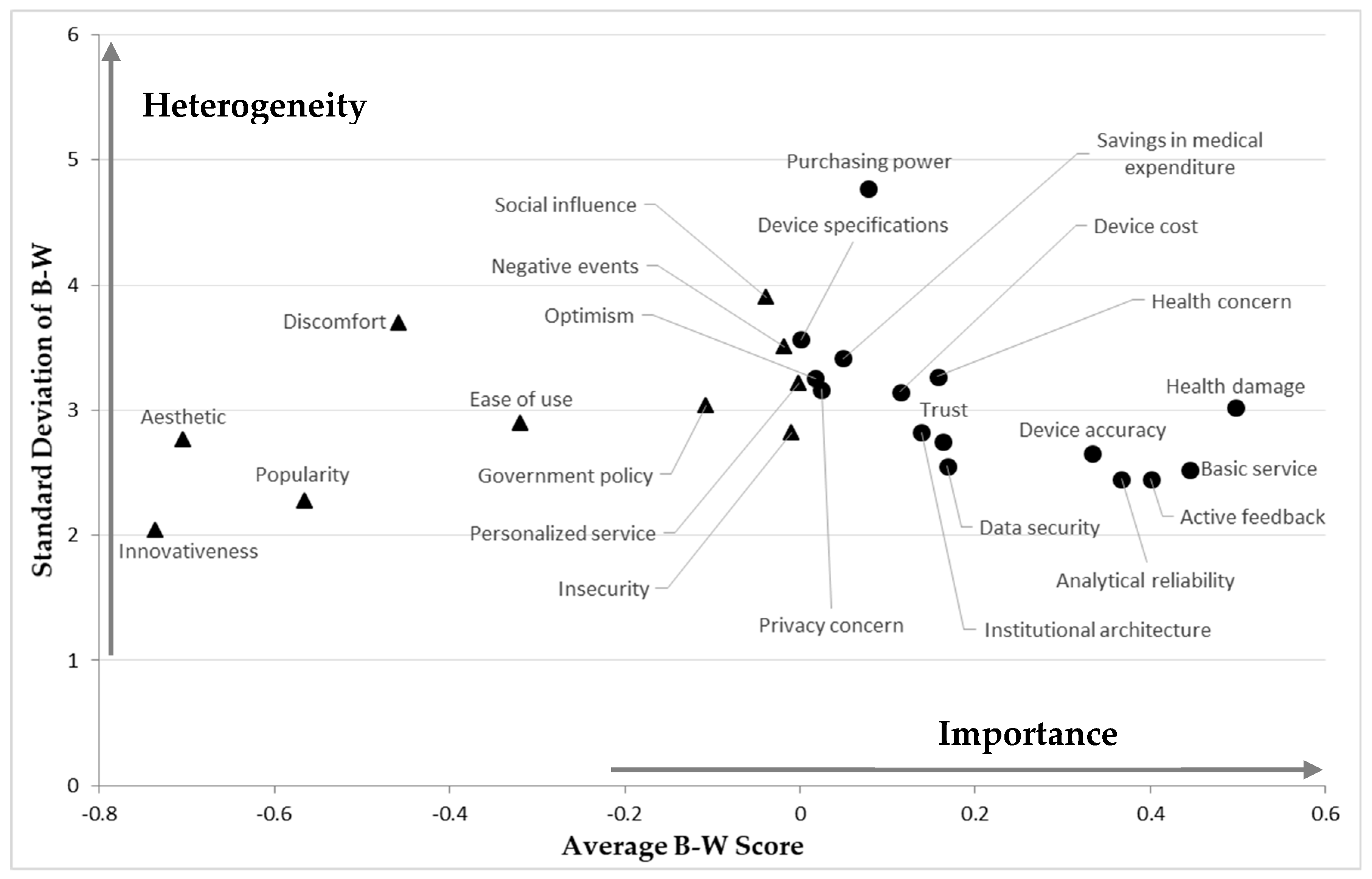

5.3. Heterogeneity of Factor Importance

6. Development of Theoretical Model

6.1. Data Collection

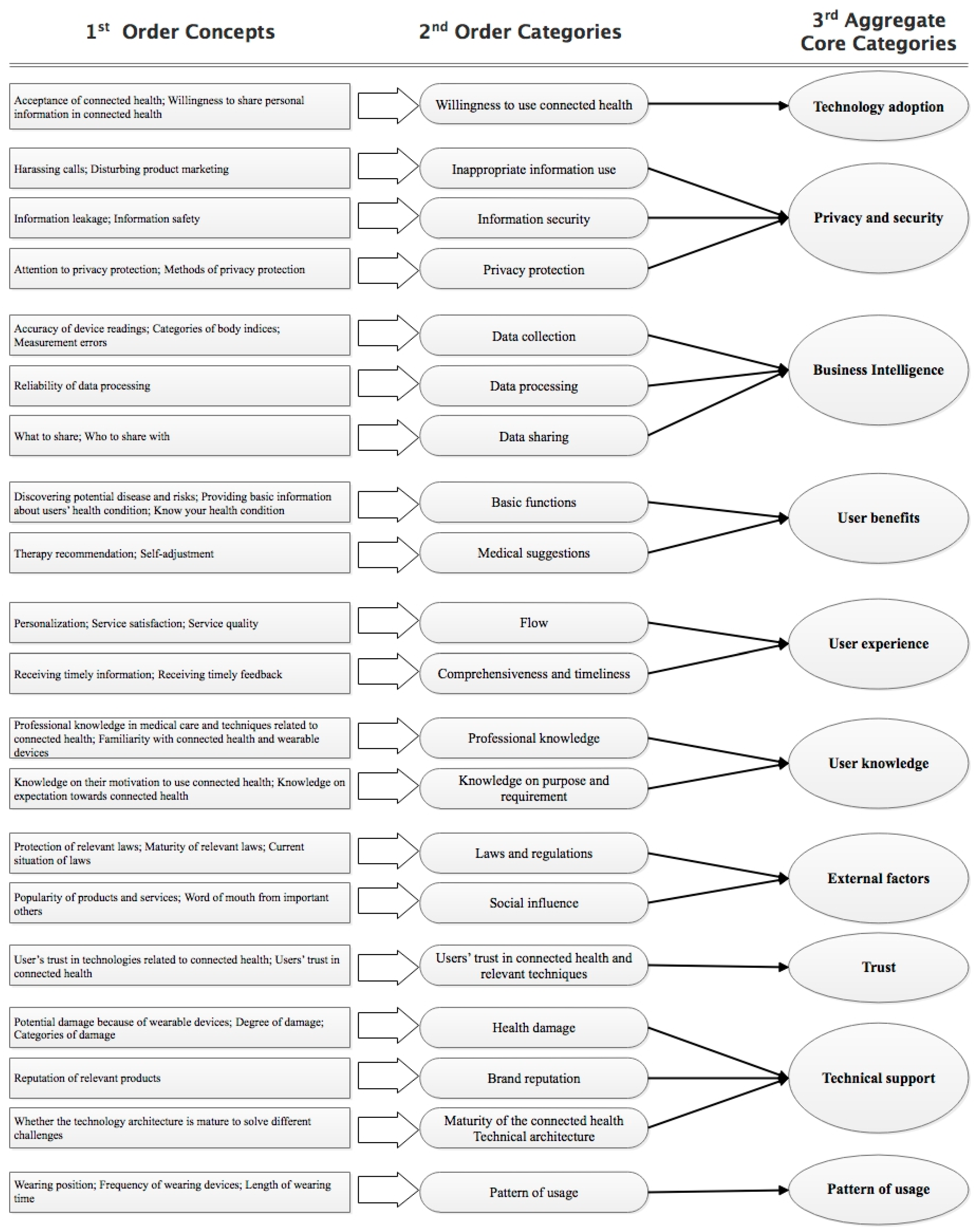

6.2. Data Analysis

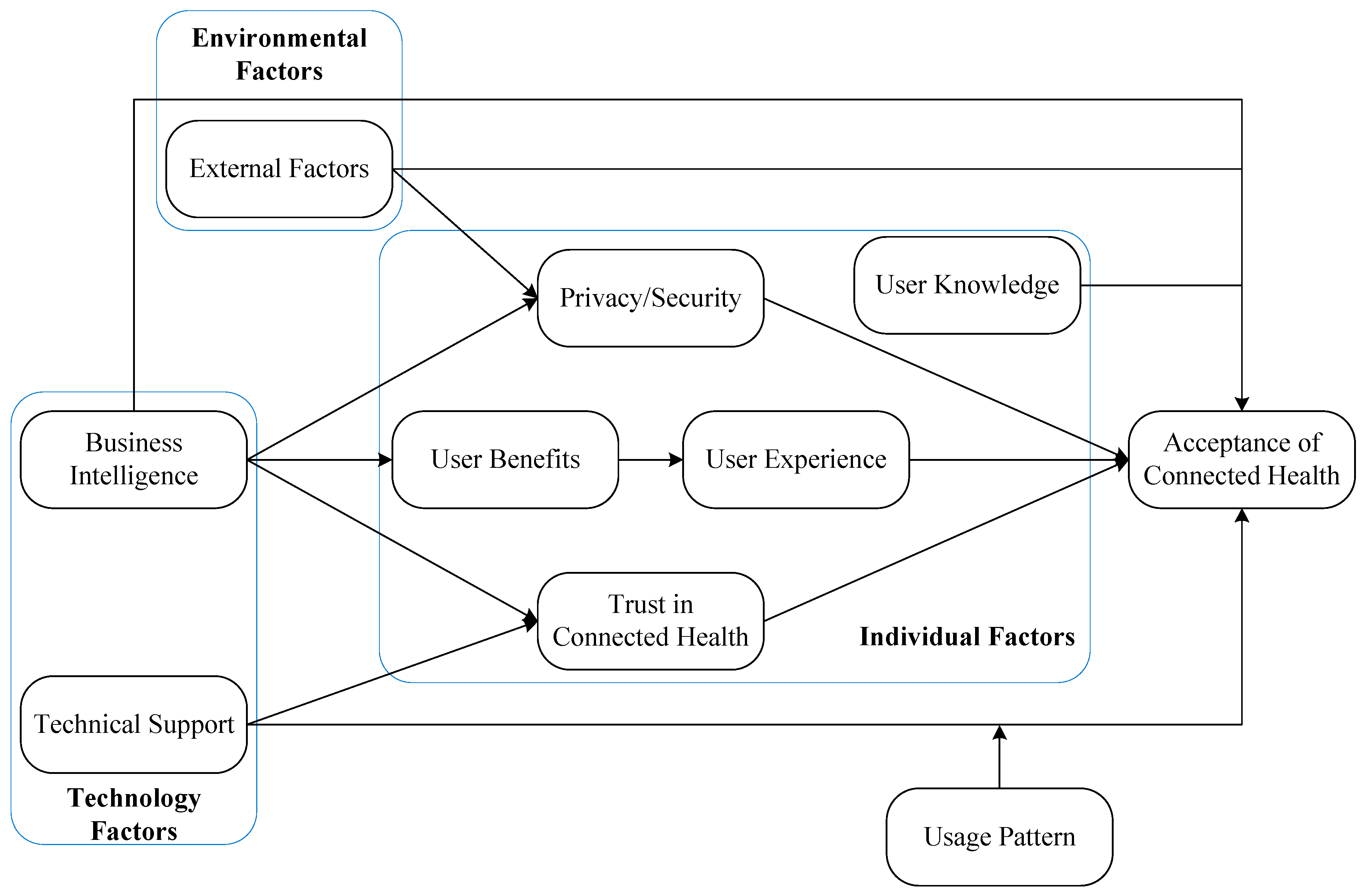

6.2.1. Technology Adoption

6.2.2. Privacy and Security

6.2.3. Business Intelligence

6.2.4. User Benefits

6.2.5. User Experience

6.2.6. User Knowledge

6.2.7. External Factors

6.2.8. Trust in Connected Health

6.2.9. Technical Support

6.2.10. Pattern of Usage

6.3. Conceptual Model from Selective Coding

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Implication

7.2. Practical Implication

7.3. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barr, P.J.; Mcelnay, J.C.; Hughes, C.M. Connected health care: The future of health care and the role of the pharmacist. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012, 18, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Integrated Care for Older People. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/guidelines-icope/en/ (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Accenture. Making the Case for Connected Health. 2012. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insight-making-casvane-connected-health (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Barr, P.J.; Brady, S.C.; Hughes, C.M.; Mcelnay, J.C. Public knowledge and perceptions of connected health. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchi, C.; Vagnoni, E. Does intellectual capital promote the shift of healthcare organizations towards sustainable development? Evidence from Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouvarda, I.G.; Goulis, D.G.; Lambrinoudaki, I. Connected health and integrated care: Toward new models for chronic disease management. Maturitas 2015, 82, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, X.J.; Ali, A.A.S.; Amira, A.; Bensaali, F. ECG encryption and identification based security solution on the Zynq SoC for connected health systems. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2017, 106, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaert, F.A.; Mazen, N.J.; Legrand, L. The tidal waves of connected health devices with healthcare applications: Consequences on privacy and care management in European healthcare systems. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, A.; Louviere, J.J. Determining the Appropriate Response to Evidence of Public Concern-The Case of Food Safety. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.M. Interpreting discrete choice models based on best-worst data: A matter of framing. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 93rd Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba, D.J. Connected health 2015: The Year of virtual patient visits. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2015, 36, 131–133. [Google Scholar]

- Harte, R.P.; Glynn, L.G.; Broderick, B.J.; Rodriguez-Molinero, A.; Baker, P.M.A.; McGuiness, B.; O’Sullivan, L.; Diaz, M.; Quinlan, L.R.; ÓLaighin, G. Human centred design considerations for connected health devices for the older adult. J. Pers. Med. 2014, 4, 245–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkins, A.; Ryan, P.; Kobb, R.; Foster, L.; Edmonson, E.; Wakefield, B.; Lancaster, A.E. Care coordination/home telehealth: The systematic implementation of health informatics, home telehealth, and disease management to support the care of veteran patients with chronic conditions. Telemed. E-Health 2018, 14, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audit Commission UK. Assistive Technology: Independence and Well-Being 4. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110601170331/ (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- O’Neill, S.A.; Nugent, C.D.; Donnelly, M.P.; Mccullagh, P.; Mclaughlin, J. Evaluation of connected health technology. Technol. Health Care 2012, 20, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caulfield, B.M.; Donnelly, S.C. What is Connected Health and why will it change your practice? QJM Mon. J. Assoc. Phys. 2013, 106, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Ajmal, M.M.; Gunasekaran, A.; Khan, M. Exploration of social sustainability in healthcare supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M.; Chakrabarti, A.K. The Processes of Technological Innovation, 1st ed.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA; Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harte, R.; Quinlan, L.R.; Glynn, L. A Multi-Stage Human Factors and Comfort Assessment of Instrumented Insoles Designed for Use in a Connected Health Infrastructure. J. Pers. Med. 2015, 5, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Netten, J.J.; Jannink, M.J.A.; Hijmans, J.M.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Postema, K. Use and usability of custom-made orthopaedic shoes. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2010, 47, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Netten, J.J.; Jannink, M.J.; Hijmans, J.M.; Geertzen, J.H.; Postema, K. Long-term use of custom-made orthopedic shoes: 1.5-year follow-up study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2010, 47, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, S.; Gray, D.; Sharp, J. Healthcare Financial Management. J. Healthc. Financ. Manag. Assoc. 2008, 71, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, D.F.S.; Almeida, H.O.; Perkusich, A. A personal connected health system for the Internet of Things based on the Constrained Application Protocol. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2015, 44, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.E.; Rice, R.E. Public views of mobile medical devices and services: A US national survey of consumer sentiments towards RFID healthcare technology. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 78, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwatzki, S.; Dytynko, O.; Trenz, M. Beyond the Personalization–Privacy Paradox: Privacy Valuation, Transparency Features, and Service Personalization. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankard, C. The security issues of the Internet of things. Comput. Fraud Secur. 2015, 9, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvedar, J.C.; Herzlinger, R.; Holt, M.; Sanders, J.H. Connected health as a lever for healthcare reform: Dialogue with featured speakers from the 5th Annual Connected Health Symposium. Telemed. J. E-Health 2009, 15, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, H.E.; Coorevits, P.; Van Maele, G.; Hutse, A.; Kaufman, J.; Ruige, J.; De Moor, G.J. Introducing telemonitoring for diabetic patients: Development of a telemonitoring ‘Health Effect and Readiness’ Questionnaire. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Dominguez Arcos, F. Applying Best-Worst Scaling in a stated preference analysis of forest management programs. J. For. Econ. 2012, 18, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Applying Best-Worst Scaling to Wine Marketing. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, G.H.; Zheng, W.F. Research on Customer Segmentation of Mobile Payment Based on Maxdiff and Latent Class Analysis. J. Appl. Stat. Manag. 2017, 36, 506–517. [Google Scholar]

- Arsham, A.; Gilles, P. Correlates of Multiple Chronic Disease Behavioral Risk Factors in Canadian Children and Adolescents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Handcock, M.S.; Gile, K.I. Comment: On the Concept of Snowball Sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2001, 41, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Xue, G.; Fu, Y.; Xu, L. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Acceptance of E-commerce Consumer Credit Service. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, C.; Lehmann, H.; Myers, M.D. Putting the ‘theory’ back into grounded theory: Guidelines for grounded theory studies in information systems. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 20, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, C.; Fernandez, W. Using grounded theory method in information systems: The researcher as blank slate and other myths. J. Inf. Technol. 2013, 28, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. The Computer Manager: A Model for Effective Performance; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere, J.; Lings, I.; Islam, T.; Gudergan, S.; Flynn, T. An introduction to the application of (case 1) best-worst scaling in marketing research. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2013, 30, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carugati, A.; Fernández, W.; Mola, L.; Rossignoli, C. My choice, your problem? Mandating it use in large organisational networks. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 6–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| O’Neill et al. [15] defined connected health as “technology aiming to provide healthcare remotely by assessing health, wellbeing and other parameters in the home whilst at the same time being connected with health care professionals through internet or phone connections” (p. 151). |

| Caulfield and Donnelly [16] defined that connected health “encompasses terms such as wireless, digital, electronic, mobile, and tele-health and refers to a conceptual model for health management where devices, services or interventions are designed around the patient’s needs, and health related data is shared, in such a way that the patient can receive care in the most proactive and efficient manner possible. All stakeholders in the process are ‘connected’ by means of timely sharing and presentation of accurate and pertinent information regarding patient status through smarter use of data, devices, communication platforms and people” (p. 705). |

| Barr et al. [4] described connected health as “a way of connecting a person with a long term-illness, for example, high blood pressure, diabetes or asthma, from their own home to the health professional (doctor, pharmacist or nurse) looking after them” (p. 249). |

| Chouvarda et al. [6] defined connected health as a mode which “aims for the optimal access, sharing, analysis and use of health data via systematic application of healthcare information technology, in other words to ‘offer the correct information to the correct person at the correct time’, so that health actors (citizens, patients, clinicians, policy makers) make better decisions for health and care” (p. 23). |

| Factor | Brief Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Technology-related (12 factors) | ||

| 1. Ease of Use | Whether wearable devices are easy to use | [20] |

| 2. Device Specifications | Wearable device technical specifications such as battery, processor performance, and product weight | |

| 3. Health Damage | Whether wearable devices will lead to health damage. For example, plastic that may cause allergic reactions | [19] |

| 4. Data Security | Whether wearables can guarantee data security | [4] |

| 5. Device Accuracy | Whether device readings are accurate | [4] |

| 6. Analytical Reliability | Whether data analysis in the process of connected health is reliable | [6] |

| 7. Active Feedback | Whether connected health can help users comprehensively monitor their body indices and receive feedback in a timely manner | [6] |

| 8. Cost | Cost that individuals should pay in order to use connected health, such as device cost, internet subscription fee, and service charge | [3] |

| 9. Aesthetic | Whether physical features of wearable devices meet the public appreciation | [20] |

| 10. Basic Service of Connected Health | Basic services that connected health can offer, such as blood glucose monitoring, chronic disease management, and identification of hidden health risks | |

| 11. Personalized Service of Connected Health | Personalized and customized medical services that become feasible with support of connected health | |

| 12. Savings in Medical Expenditure | Whether connected health will help reduce individuals’ medical expenditure | [23] |

| Individual-related factors (8 factors) | ||

| 13. Optimism | Whether users think connected health will offer people increased control, flexibility, and efficiency | |

| 14. Innovativeness | Whether users want to conquer new technology | |

| 15. Discomfort | Worry about being controlled by connected health | |

| 16. Insecurity | Worry that connected health can’t work as normally as expected | |

| 17. Trust | Whether users trust connected health | [4,24] |

| 18. Health Concern | The extent to which users are concerned over their health | |

| 19. Privacy Concern | The extent to which users are concerned over privacy | [8,25,26] |

| 20. Purchasing Power | Individual purchasing power | |

| Environment-related factors (5 factors) | ||

| 21. Social Influence | Influence of importance, such as doctors’ advice | [1,4,27] |

| 22. Government Policy | Whether the government implements policies to facilitate the development of connected health | [22] |

| 23. Institutional architecture | Whether there is legislation and technological architecture that can guarantee user concerns, such as data security | |

| 24. Negative Events | Negative events that are closely related to user concerns, such as data leakage events | |

| 25. Popularity | Popularity of connected health | [28] |

| Question Number | Choices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | 23 | 14 | 20 |

| 2 | 6 | 18 | 15 | 7 |

| 3 | 21 | 15 | 14 | 11 |

| 4 | 24 | 25 | 1 | 7 |

| 5 | 4 | 10 | 23 | 15 |

| 6 | 18 | 21 | 10 | 2 |

| 7 | 22 | 10 | 1 | 12 |

| 8 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 25 |

| 9 | 10 | 5 | 24 | 6 |

| 10 | 6 | 13 | 21 | 12 |

| 11 | 18 | 24 | 19 | 11 |

| 12 | 9 | 22 | 24 | 4 |

| 13 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 20 |

| 14 | 17 | 8 | 19 | 20 |

| 15 | 5 | 21 | 8 | 22 |

| 16 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 24 |

| 17 | 3 | 25 | 18 | 13 |

| 18 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 18 |

| 19 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 5 |

| 20 | 3 | 9 | 19 | 10 |

| 21 | 23 | 21 | 16 | 3 |

| 22 | 20 | 18 | 12 | 5 |

| 23 | 21 | 7 | 24 | 17 |

| 24 | 13 | 2 | 22 | 25 |

| 25 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 1 |

| 26 | 13 | 19 | 23 | 1 |

| 27 | 3 | 7 | 20 | 22 |

| 28 | 23 | 18 | 9 | 8 |

| 29 | 1 | 8 | 15 | 20 |

| 30 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 25 |

| 31 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 16 |

| 32 | 14 | 2 | 9 | 17 |

| 33 | 22 | 18 | 14 | 16 |

| 34 | 20 | 13 | 9 | 11 |

| 35 | 17 | 10 | 14 | 13 |

| 36 | 2 | 6 | 16 | 19 |

| 37 | 16 | 25 | 20 | 10 |

| 38 | 5 | 15 | 13 | 19 |

| 39 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| 40 | 19 | 7 | 12 | 14 |

| 41 | 17 | 22 | 15 | 16 |

| 42 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 8 |

| 43 | 2 | 23 | 7 | 12 |

| 44 | 23 | 11 | 6 | 22 |

| 45 | 4 | 25 | 19 | 21 |

| 46 | 23 | 5 | 17 | 25 |

| 47 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 16 |

| 48 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 21 |

| 49 | 16 | 24 | 8 | 13 |

| 50 | 24 | 23 | 14 | 20 |

| Suppose that you need to consider whether to use connected health. Between the four choices listed in each question, please select one choice that has the greatest impact and another choice that has the least impact on your decision. | ||

| Most important | Choice | Least important |

| ◻ | Negative events that are closely related to user concerns such as data leakage events | ◻ |

| ◻ | Whether there are legislation and technological architecture that can guarantee user concerns such as data security | ◻ |

| ◻ | Whether users want to conquer new technology | ◻ |

| ◻ | Individual purchasing power | ◻ |

| Factor No. | Factor | Total Best | Total Worst | B–W Score | Average B–W Score | Std of B–W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Health damage | 780 | 57 | 723 | 0.497 | 3.023 |

| 10 | Basic service | 728 | 81 | 647 | 0.444 | 2.521 |

| 7 | Active feedback | 663 | 80 | 583 | 0.4 | 2.451 |

| 6 | Analytical reliability | 616 | 82 | 534 | 0.367 | 2.451 |

| 5 | Device accuracy | 594 | 108 | 486 | 0.334 | 2.652 |

| 4 | Data security | 433 | 188 | 245 | 0.168 | 2.556 |

| 17 | Trust | 405 | 167 | 238 | 0.163 | 2.75 |

| 18 | Health concern | 428 | 199 | 229 | 0.157 | 3.272 |

| 23 | Institutional architecture | 360 | 158 | 202 | 0.139 | 2.822 |

| 8 | Device cost | 416 | 249 | 167 | 0.115 | 3.146 |

| 20 | Purchasing power | 475 | 361 | 114 | 0.078 | 4.776 |

| 12 | Savings in medical expenditure | 385 | 313 | 72 | 0.049 | 3.417 |

| 19 | Privacy concern | 263 | 227 | 36 | 0.025 | 3.167 |

| 13 | Optimism | 332 | 306 | 26 | 0.018 | 3.255 |

| 2 | Device specifications | 353 | 352 | 1 | 0.001 | 3.565 |

| 11 | Personalized service | 340 | 342 | −2 | −0.001 | 3.216 |

| 16 | Insecurity | 286 | 300 | −14 | −0.010 | 2.818 |

| 24 | Negative events | 294 | 321 | −27 | −0.019 | 3.507 |

| 21 | Social influence | 353 | 409 | −56 | −0.038 | 3.9 |

| 22 | Government policy | 228 | 385 | −157 | −0.108 | 3.036 |

| 1 | Ease of use | 126 | 590 | −464 | −0.319 | 2.899 |

| 15 | Discomfort | 149 | 815 | −666 | −0.457 | 3.699 |

| 25 | Popularity | 28 | 850 | −822 | −0.565 | 2.279 |

| 9 | Aesthetic | 46 | 1070 | −1024 | −0.703 | 2.76 |

| 14 | Innovativeness | 19 | 1090 | −1071 | −0.736 | 2.042 |

| Technological Factors | Individual Factors | Environmental Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most important (B–W > 0) |

|

|

|

| Least important (B–W < 0) |

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, L.; Tan, Y.; Han, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Factors Affecting Chinese Young Adults’ Acceptance of Connected Health. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082376

Jia L, Tan Y, Han F, Zhou Y, Zhang C, Zhang Y. Factors Affecting Chinese Young Adults’ Acceptance of Connected Health. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082376

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Lin, Yuting Tan, Feiyu Han, Yi Zhou, Chu Zhang, and Yufei Zhang. 2019. "Factors Affecting Chinese Young Adults’ Acceptance of Connected Health" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082376

APA StyleJia, L., Tan, Y., Han, F., Zhou, Y., Zhang, C., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Factors Affecting Chinese Young Adults’ Acceptance of Connected Health. Sustainability, 11(8), 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082376