Abstract

Since the 1940s, the Costalegre, on the Pacific coast of Mexico, has been recognized as having a high potential for tourism. The aim of this paper is to understand tourism governance in a place where past and emergent luxury tourism co-exists with small-scale tourism in a largely rural and ecologically important landscape. We conducted in-depth interviews with 29 different stakeholders and administered a questionnaire survey to 27 tourist establishment owners and employees. We also held a workshop with 11 families from three rural communities and administered another questionnaire to a further 125 people from the same localities. Policy document analysis and participant observation completed the research. We found there to be strong discrepancies between the federal government’s legal framework for tourism development and local views and attributes for action. Owners and new investors in luxury tourism developments are well organized and have the economic and political power to obtain authorization for their projects, even in cases where the projects have received negative assessments from environmental scientists. We discuss how an ineffective local governance mode enables the wealthy part of the private sector to prevail, jeopardizing the construction of a regional strategy that is socially just and takes into account the needs of local residents.

1. Introduction

Mexico ranks eight in international tourist arrivals with more than 35 million visitors in 2016 [1]. The Mexican economy relies on tourism and, with more than 11 thousand kilometers of coastline along the Caribbean and the Pacific oceans, is particularly dependent on sun and beach tourism. Situated between Puerto Vallarta and Manzanillo, two of Mexico’s most significant tourist destinations on the Pacific coast, the Costalegre region has been identified as having important marine and terrestrial ecosystems with great biological diversity [2,3,4]. Tourism has grown slowly in the region, although for more than seven decades it has been promoted as an industry that could bring economic benefits to the region [5]. Its development has been mainly in the hands of a few European and Mexican entrepreneurs who own luxury mansions, villas, and a few hotels [6]. In recent years, larger luxury tourism projects (although not as large-scale as in Cancun or Puerto Vallarta) have spread and continue to do so. In 2007, scientists from The National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM for its acronym in Spanish) demonstrated the negative environmental impacts that one of these projects would have and were able to stop its development [7]. However, the Mexican environmental authorities, ignoring the arguments provided by scientists regarding the threats to the local social-ecological systems [8], later approved this project and others.

It is against this backdrop that this paper aims to analyze the relationship between the state (understood as the public sector in Mexico), the private sector (those involved in the tourism industry), and the local communities in Costalegre. In order to understand tourism governance, our study starts by examining the existing tourism infrastructure. Because Costalegre is an isolated place (with no banks or gas stations), tourist accommodation is limited to small hotels and rooms to let for local and regional visitors and, on the other hand, there are high-end hotels and resorts for international visitors (such as politicians and Hollywood actors) who enjoy isolated places with beautiful beaches and landscapes (no available records existed of the establishments). We analyzed the legal framework from which tourism is planned and executed and the ways in which local government and the private sector manage tourism. We documented the views of local residents, as well as the role that environmental issues play in the region. We believe that an understanding of governance processes will help to identify ways of transforming institutions, and of redefining the roles of individuals and groups in order to support a regional sustainable tourism plan for the Costalegre region.

2. Conceptual Framework

The classical understanding of governing, where the boundaries between the public and private spheres were strict, has radically changed. Governing (i.e., having control or rule over oneself) was an issue that had to do exclusively with the government (i.e., the office, authority or function of governing), organized through hierarchies, with responsibility for public affairs consigned to the public domain of the state [9]. From this point of view, public management was formal, legalistic, and oriented to rules [10]. Nowadays, it is increasingly common to see how civil society actors and business interest associations co-produce public regulations and are heavily involved in lobbying to shape regulation, both national and internationally [11]. This situation occurs in a neoliberal world arena, where the institutions of global governance, in addition to having virtually no regulatory capacity at the business level, promote schemes and discourses of self-governance and voluntary certification [12]. In these new governance arrangements, it is difficult to clearly establish the limits between public and private interests. In the context of weak or indifferent states, private interests can take control and reframe environmental action as a means to legitimize their model of development [13].

Historically, in Mexico the government has been in charge of most governing decision-making processes. However, as has happened with many other countries, the allocation and control of resources, and the coordination, policy formulation, and implementation of projects are no longer exclusively the government’s domain [14,15]. Non-state actors such as civil associations are not only interested in participating in the formulation and implementation of policies and plans but have questioned the role of the state in society and have been advocating for more democratic ways to exercise power [16].

Although there are multiple definitions, governance can be understood as the activity of governing [9]. Governance emerged as a notion to foster decision-making arenas in society, and bring legitimacy to political processes. Governance, according to Vatn [17], should enable society to define the rights and responsibilities of diverse social actors and their institutional structures. It should establish a framework for addressing the relationships and interactions between state interventions and societal self-regulation [18,19]. As Bramwell and Lane [20] (p. 412) say, governance involves “processes for the regulation and mobilization of social action and for producing social order”. Related to tourism, governance has acquired special relevance in the context of moving the industry towards sustainability—that is, recognizing the need to maintain the ecosystems that support life on Earth, including human life, while simultaneously ensuing well-being is secured for all societal groups [21]. Tourism governance studies have shifted towards the understanding of social relationships between government, business networks, and civil society, emphasizing the access and role of community groups in decision making processes [22]. As Beaumont and Dredge [23] argue, effective tourism governance depends on the effectiveness of institutional structures and processes, but also on the maturity and strength of local organizations (i.e., local government, civil society, and business actors), including the personal as well as the professional characteristics of those involved. The need of critical analysis of socio-political structures and drivers behind the way the industry works in the context of present neoliberalism is advocated [24,25]. Issues of power are examined making visible how economic and political interests are frequently adverse to local communities at tourism destination sites [19,26]. The need to construct platforms of negotiation among all stakeholders, is considered a key aspect of sustainable tourism and the role of trust and justice are aspects that need to be examined in order to provide insights and promote a transition towards sustainable tourism [12,27].

Environmental governance places an essential role in sustainable tourism and it has come to be of central importance in the construction of institutional arrangements aimed at mitigating human impacts on the natural environment [17]. In recent years, human–nature interactions have been described through the concept of social-ecological systems, which emphasize how natural and human systems have been integrated since humans appeared on Earth [28]. Their separation is artificial and thus they need to be examined as linked systems at different and hierarchical scales [29,30,31].

In this paper, our concern is to analyze the interactions among stakeholders in the context of tourism governance in the Costalegre. We look at the facilities and establishments for tourists and the multiple interactions that occur between stakeholders, particularly in the context of decision-making processes, and the opportunities and constraints that reveal either a stakeholder’s inclusiveness and effectiveness or their exclusion from such processes [18,32]. We discuss critically the capacity of the state to “steer” the social-ecological system and their relationships with other policy actors, as well as how effective governance requires interactions among stakeholders to be institutionalized, and that contradictory interests must be negotiated and settled if decision-making processes and the exercise of power are to be effective. We developed an actor oriented research perspective that helped us make visible those social issues that are obstacles to effective and legitimate governance [26].

3. Study Area

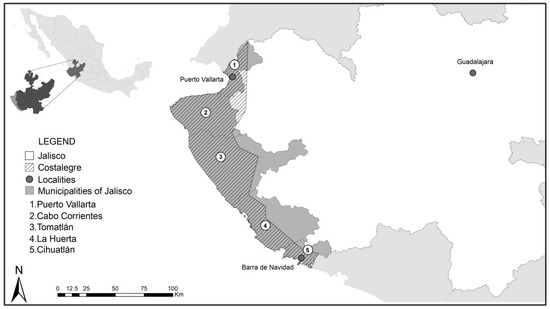

Costalegre was created as a touristic corridor to connect two major tourist sites on the Mexican Pacific coast, Puerto Vallarta and Barra de Navidad [33]. It comprises the coastal areas of four municipalities: Cihuatlán, La Huerta, Tomatlán, and Cabo Corrientes, covering an area of 300 km of coastline (see Figure 1). While our focus for this study was on La Huerta Municipality, we also looked at relevant regional and federal actors and their cross-level interaction.

Figure 1.

Study area showing the location and composition of the Costalegre region. Guadalajara is the city capital of the Jalisco state. The focus of the study is the coast part of La Huerta Municipality (Number 4).

The Costalegre region is sparsely populated. In 2000 there was a population of 23,000 (11.8 habitants/km2) with a growth rate of 2.6% [34]. By 2015 the total population had risen to just 24,563 [35]. Land tenure is either communal (named social property), mainly ejidos (institutions created after the 1910–1917 Mexican revolution for collective land management; [36]), private, or state owned. Overall, 25% of the area is privately owned and 75% is regarded as social property. In La Huerta, 80% of the land is under collective management and 20% in private and state regimes [37].

The development of tourism infrastructure in Costalegre began very soon after the completion of the Jalisco coastal road in 1971 and the international airport of Playa de Oro in 1974. Construction of the road between Barra de Navidad in the South and Puerto Vallarta in the North began in 1965, and advanced steadily. According to one government document from 1970, “The road is 215 kilometers long and is fundamental for the economic integration of the region. It has started to be paved” [38] (p. 11). The completion of the road was an historic event in the coast of Jalisco, as was the inauguration of the international airport in 1974, partly financed by Antenor Patiño, the Bolivian millionaire who also built the hotel Las Hadas, near Manzanillo. The road and the airport sparked the development of the region, especially for tourism, with the arrival of Club Méditerranée to Playa Blanca, between 1971 and 1974, and the construction of Hotel Plaza Careyes, between 1973 and 1976 [6,39]. The road and the airport also facilitated the establishment of research and conservation agencies in the region, in particular the Chamela Biological Station of UNAM in 1971 and the Cuitzmala Ecological Foundation in the late 1980s. Much of what is considered to be part of the tourism industry is actually “residential tourism”, whereby people from other countries (mainly Europe, Canada, and the United States) come for long periods of time [40]. Initially attracted by the year round warm climate and the beauty of the beaches, many of these residential tourists now own houses and big mansions along the coast. Cutting off access to public beaches has become common practice in Costalegre, and contact with the local rural communities is generally limited to the provision of jobs for cleaners, cooks, and security guards.

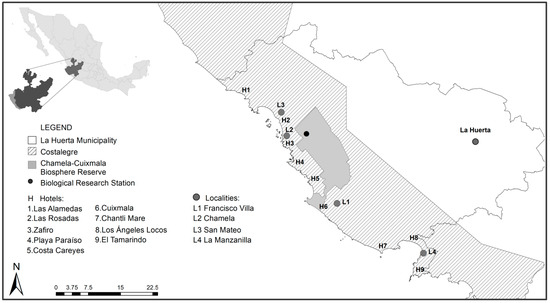

The ecology of the Costalegre region has been studied extensively by the Chamela Biological Research Station [41,42]. In 1993, the research station’s land, along with approximately 10,000 ha owned by the Cuixmala Ecological Foundation (created by a wealthy European family), was decreed as the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve (Figure 2) protecting 13,142 ha of tropical dry forest [43].

Figure 2.

Important localities and hotels of the study area.

4. Research Approach and Methods

A place-based research approach [44] using mixed methods [45] was used to fulfill our study’s objectives. We analyzed documents including government programs and legislation as well as tourism proposals in order to understand what is written as governmental aims regarding tourism and to see how decisions are made on the site. Interviews and context-based surveys were conducted during field trips in the period 2012–2015, and we also practiced participant observation whenever possible. Secondary sources, including public records, websites, newspapers and published interviews, were also consulted. We triangulated our findings drawing on these different methods. We conducted 29 semi-structured in-depth interviews with governmental agents, luxury hotel owners and tourism developers (see Figure 2 and Table 1). The interviewees were chosen by drawing on our experience of more than 15 years in the study area and through a snowball sampling method [46]. The main groups of stakeholders interviewed are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interviews conducted divided by sectors; total number of interviewees per sector is given in parenthesis. Most interviews were individual although some people had more than one responsibility. Focus groups are indicated when more than one person participated. AECA is the Costalegre Association of Tourism Entrepreneurs. UNAM, the National Autonomous University of Mexico and UdG University of Guadalajara. * Owners and administrators who never accepted to give an interview; information was obtained from published documents. ** Information from the private local sector was obtained from interviews of local hotels and tourism initiatives and also through a survey.

In order to achieve our research objectives, the content of the interviews varied with each interviewee according to their social sector and included: the role of tourism in the region (to start talking about the main theme); the identification of and relationships with other actors (to document views regarding social roles and interactions); the role of the local population (to document the views towards rural people because of the strong differences in livelihoods); and the relation of tourism to environmental issues (because of the fragility of the local ecosystems and the potential affectations if more tourism developments are built). Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed with the help of Atlas.ti (Version 7). Data were coded identifying the ideas provided by interviewees, which then served to construct explanations [47]. A survey with both open-ended and closed questions was administered to 27 owners or employees of local low and middle range hotels who agreed to answer the survey (21 low and middle class hotels, five bungalows, and one camping ground, of these 16 interviewees gave extended answers). To gain insights into the relationships local inhabitants have, or perceive themselves to have, with current and future tourism developments, a workshop was held with 11 families from three local communities (Francisco Villa, Chamela and San Mateo; see Figure 2). A survey with open-ended and closed questions was also administered face-to-face with 125 adult members of households in these localities (64 in Francisco Villa, 22 in Chamela, and 39 in San Mateo). The number of interviews was related to the total number of inhabitants in each locality. We followed the guidelines of probability sampling [48], using maps of the localities. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze surveys and we documented all information exchanges and proposals from the workshops. At all times, we followed an ethical code of conduct and had the informed consent of participants.

A report was given to the communities, which can be found at [49]. All acronyms used are the names of institutions in Spanish.

5. Results

5.1. Tourism Infrastructure in Costalegre

Our case study shows great discrepancies between official and actual records of the tourism industry. Table 2 shows the figures found in official documents, which contrast with our own data collected using Google maps, field visits by land and sea, and from information obtained through websites. It had taken four to five decades to generate the number of rooms available at the time of our research. Table 3 presents information regarding Luxury hotels shown in Figure 2. It is clear from government records that a significant number of tourism facilities have not been registered in Costalegre, and this has implications on the role government is playing to regulate tourism.

Table 2.

Tourism establishments in the municipality La Huerta. Comparison of official statistics and fieldwork data (2013–2014); numbers in parenthesis correspond to number of rooms. Sources: [35] and * Costalegre’s Regional Tourism Office (this office does not register private mansions and houses).

Table 3.

Hotels and luxury establishments for rent in La Huerta municipality (El Tamarindo is located in Cihuatán municipality in the border with La Huerta). Sources: [6], hotel web pages and telephone calls.

While the majority of the registered low- and mid-range establishments operate largely during the main holidays (Christmas, Easter, and Mexican summer holidays), bigger hotels, luxury hotels, and private mansions are open all year round. Generally speaking, Costalegre’s tourism is mainly dependent on national tourists during the main holidays and on international seasonal tourism, such as snow birders from Canada and the United States during the winter months. As in other parts of Mexico, international tourists often become long-term residential tourists and second-home builders [50,51]. One prime example of this type of residential tourism is the case of La Manzanilla (see Figure 2), formerly a small fishing village with 1037 inhabitants which is now dedicated to tourism for at least half the year. Besides nine officially registered hotels and a further 21 not officially registered but nevertheless operational establishments offering 223 rooms, there are almost 500 rooms in 166 privately rented homes and bungalows (estimates based on an average of three rooms per bungalow). Tourism officials see this kind of “informal tourism” as one of the main challenges to Costalegre’s tourism offer. At the time of our fieldwork several new combined real estate and tourism projects in the La Huerta municipality were being proposed, some of which are now under construction (Las Rosadas and Zafiro). Table 4 lists proposed projects and the available information shows an increase of more than four times the number of rooms (see also Table 2).

Table 4.

Planned tourism projects. Based on revision of respective Environmental Impact Assessments. * Zafiro was first presented as IEL La Huerta and La Tambora. Source: [52].

5.2. The Legal Context: Tourism Policy and Instruments

This section and the following present the extent of governmental organization of tourism and show that legislation and programs on paper have little impact on the day-to-day decisions made in Costalegre. Tourism in Mexico has a governmental framework that includes agencies from the federal to state and municipal levels. Regional offices based in strategic locations are also important regarding tourism development. Table 5 lists the main governmental agencies and the plans and programs that shape tourism development in Costalegre.

Table 5.

Main tourism agencies, plans, and their goals for the different levels of government. Acronyms of governmental agencies come from the names of institutions in Spanish. POETCJ refers to the Land Use Program of the Jalisco Coast decreed in 1999.

The Sectorial Tourism Program 2013–2018 is the main planning instrument for tourism policy in Mexico that takes into account environmental legislation. At the state level, there is the Promotional Tourism Law of the State of Jalisco, which regulates plans and promotes tourism activities and infrastructure projects in Jalisco and its municipalities. Our analysis of the documents presented in Table 5 found that they strongly advocate for tourism to be planned and coordinated, not only at different governmental levels but also among stakeholders and agencies focused on improving local people’s well-being through employment generation and through ensuring an efficient and sustainable use of natural and cultural touristic resources. However, not only do the multiple programs and land use plans sometimes contradict each other, but many are also outdated and are not implemented at the local level. As the following sections show, the intersectorial involvement in tourism development stipulated in the legal documents rarely occurs.

5.3. Tourism Management in the Public Sector

The role of the federal government regarding tourism is to coordinate planning activities in each federative entity, establishing the baselines to achieve goals that ensure the democratic participation of social actors [53]. Federal Tourism Law stipulates that advisory tourism boards with representatives from both public and private sectors must be established, and that their task is to analyze tourist developments, provide advice, and propose actions that take into account all stakeholders, including municipal presidents.

The strategic plans for Seturjal (see Table 5), in Jalisco, include the creation of new tourist products and destinations as well as the maintenance and upgrading of existing infrastructure. However, this governmental office’s role is mainly restricted to creating links between investors and the public administration. Costalegre’s Regional Tourism Office is a central office with premises in Barra de Navidad (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Apart from liaising with tourists and tourism providers, its role is to document and promote tourism development and to monitor prices and services. The Commissioner of this regional office explained that although they conduct surveys and gather data about tourism they do not have an executive mandate. Only the municipalities and the Jalisco State can take concrete action in tourism management, whether it is for new developments or regarding existing law enforcement. Municipalities have their own juridical powers and can formulate, approve and administrate urban developments, public services, and land use, including the authorization of new tourism developments. In La Huerta, there was no official Tourism Department until the administration of 2012–2015, when an office was established within the department of Economic Development. In order to promote more interaction between the municipality and the whole range of tourism entities, The Tourism Promotion and Development Board of Costalegre (Coprofotur) was established in 2010. The mayor, in an interview at the time, emphasized that “tourism should be the launching pad of the municipal economy and we are open to work with the private sector, to support them and foment investments in order to develop the coastal zone.” Other municipal agents highlighted serious limitations to the development of the tourism sector, such as a lack of resources and qualified personnel, corruption, mixed priorities and a dependence on short-term solutions. As the mayor said: “sometimes the need to generate employment options leads to not paying attention to, for instance, environmental issues”.

5.4. The Private Tourism Organizations: How They Work and Interact with Other Actors

The main findings show that the tourism private sector is heterogeneous; there is a wide variety of hotel types in the area (from small Mexican hotels to high-end resorts aimed at the international sector) and, overall, they are not well organized). Concerning the existence of Coprofotur, five out of 10 hotel owners or administrators interviewed acknowledge that it only meets sporadically and not all tourism entities are well represented at meetings. Also, one medium size hotel owner explained: “It is not always convenient to attend meetings because it involves a lot of time and gasoline to move to places and the discussions frequently lead to no outcome”. Other respondents had similar opinions (eight out of 16 considering interviewees from the private sector, see Table 1). The vast majority of Costalegre’s smaller hotels do not belong to any formal organization, although there are associations such as the Society of Hotels, Motels, and Restaurants of Costalegre. According to the Regional Tourism Office Commissioner, however, members of such associations do not meet frequently and thus they do not play an important role.

In Mexico, official hotel categories have up to five stars. However there are also the so called High-end, Luxury and Boutique hotels and, in Costalegre, there are as well, luxury mansions which provide tourism services to a wealthy elite. These places function independently and, as the Commissioner of the Regional Tourism Office pointed out: “this diversification of actors does not help to create an image of cooperation or to create unity or a common position regarding the future of Costalegre”. However, luxury hotel owners and tourism developers told us that they were not satisfied with existing tourism organizations. For this reason, in 2010 they set up the Association of Tourism Entrepreneurs of Costalegre (AECA, for its acronym in Spanish) with the aim of giving Costalegre a strong voice regarding possible new investors. According to six out of 10 interviewees (those from the luxury hotels, see Table 1), AECA has taken over Coprofotur’s role and claims to “represent the majority of the important hotels”. This private association is composed of selected members of the luxury tourism and real estate developers of Costalegre. As their president explained: “AECA is a facilitator for any investor; we try to reunite the voice of all developers and give them a stronger voice.” The organization is highly active and is seen as working closely with the federal and the Jalisco state tourism agencies.

We separately surveyed 27 representatives of low and mid-range establishments from which we present results of the 16 who gave extended answers (see section on Methods). The majority (12 of 16) had a clear idea of Costalegre as a geographic tourism area and felt part of it. However, 13 out of 16 had never heard of any form of tourism organization and 10 out of 16 did not know of any formal Costalegre related tourism office. Yet, at least three respondents were personally in contact with the Regional Tourism Office. As mentioned before, these tourism establishments were not part of any formal organizations at village or regional level, partially due to their informal character. This has resulted in a perception that they have been “abandoned” by municipal and other official tourism agencies.

5.5. The Perspectives of the Local Inhabitants

The three localities that participated in our workshop were Chamela where fishing is the main economic activity and it is located close to Zafiro, the ejido San Mateo dedicated to livestock raising and is near Las Rosadas, and Francisco Villa, a locality with a longstanding history of service provision for luxury tourism developments. The first finding of the workshop was that people do not see their localities as touristic sites per se. The participants assessed their livelihoods through talking about future or ideal scenarios. The analysis of these revealed that participants from all three localities hoped to have, first and foremost, clean environments, especially rivers, followed by better education (qualified teachers) and community infrastructure (better school buildings, a library, recreation spaces). All localities wanted to improve their urban image through the construction of recreation facilities such as parks or plazas, paved roads and sidewalks; freshly painted houses; and the improvement of public services and public transport. Respondents said they were not satisfied with the income they derived from traditional activities. For example, according to one man from San Mateo: “Livestock production means a lot of work, needs a lot of supplies, there are no holidays, and it is chicken feed.” Respondents from Chamela expressed the need to modernize fishing methods because the traditional ways do not enable them to make enough of a living. The need to establish local markets with fair prices was also mentioned. San Mateo’s inhabitants mentioned as well the problem of freshwater availability. As one participant said, “as you know there is little water, it may be enough for the inhabitants but not enough for tourism”. Although participants acknowledged a high attachment to their communities as well as to the surrounding ecosystems, they also identified important areas for improvement, although no one expressed a direct interest in partaking in the tourism industry. In the final discussion at the workshop several negative consequences of tourism were raised that are the result of poorly planned developments; respondents remembered when there had been a lack of negotiation between rural local inhabitants, authorities, and tourism developers. As one man said “There are two options: either you don’t grow and don’t get any tourism or you grow and get also negative tourism consequences”.

The Chamela Research Station of UNAM was identified as a main obstacle to tourism development because scientists and conservationists are perceived as having, as expressed by a workshop participant, “lack of understanding of the people’s realities”. Our workshop participants acknowledged that group exercises involving members from the same localities, coupled with a plenary session where everyone had a chance to express their ideas, were effective methods for sharing different points of view between local villages and identifying common interests and concerns. The need for local communities to cooperate was expressed repeatedly. For example: “Together we have to bring the region forward for the sake of our children” and “we have to organize ourselves and not wait for the government to help us, then it is possible to change”.

We incorporated these first impressions about the relationship between local villagers and existing and future tourism developments into our questionnaire survey applied to 125 adults (see section on Methods), which more women than men answered, representing the family views (62%). As in the workshop, nearly all respondents saw their region as touristic (97.6%), citing examples of nearby tourism sites and beaches, however, rather than their own villages (90.4%). A third of respondents attributed the lack of tourism in their villages to a lack of developed sites of touristic interest. About 50% of respondents said that tourism had always been present in the region, or at least for the last 10 years, and identified foreigners as leading actors. According to 67% of people surveyed, tourism has declined in recent years mainly due to closed beach access and the closing of the big hotels (Club Med, part of hotel Costa Careyes and El Tamarindo). Thirty percent of respondents said there had been an increase in tourism due to a shift from conventional hotel tourism to private luxury housing options; 79% acknowledged an indirect relationship between their income and tourism, with 19% saying that their employment was directly related to tourism (activities such as gardening, housekeeping, maintenance, and clerical work). Almost 80% spoke of indirect family income coming, for example, from temporary and/or seasonal work in construction, or owning or working in local businesses such as shops or restaurants. Respondents also mentioned boat trips offered by fishermen (16%), family members working in tourism to help boost the family’s income (14%), and the informal selling of products such as soft drinks, cut fruit or handicrafts (7%). Twenty nine percent said tourism had helped to boost the local economy. Overall, respondents believed that tourism development is compatible with existing economic activities (75%), however many were unsure whether or not tourism developments take into account local needs and priorities (50% in the three localities).

When asked to identify projects currently under construction, respondents first mentioned Zafiro, then Las Rosadas and the remodeling of the hotel Costa Careyes. Of respondents 62% in Chamela, 69% in San Mateo, and 52% in Francisco Villa said they were in favor of these new projects, and some 30% were unsure of their view. Those in favor argued for the generation of better paid employment options, the revival of local livelihoods and overall economic growth. Among the reasons against the developments were the closing of beach access and beach restaurants, disturbances to the peace, the large influx of foreigners, and changes in people’s livelihoods. Comments such as “it is not the same as before” were frequent. There were no major differences between the three localities in general perceptions and expectations regarding the new tourism projects so we have presented the results for the whole study population. Of the study population 88% was generally in favor of more tourism in their locality and 73% was keen for existing developments such as hotel Costa Careyes to reopen. The new projects are seen as bringing hope (85%) and more order and cleanliness (63%) to the villages. Although there was a strong perception that, at the time of our fieldwork, there was not much tourism-related employment, 87% of the respondents agreed with the statement “there will be more tourism employment in the future” and also 85% agreed that tourism will generate spin-off business opportunities. Of all respondents 77% agreed that tourism-related jobs will help keep the youth in the region. For example: “At the beginning I was against it, but the fishing is not going well. There will be a lot of employment; before, those who studied who usually leave the community, now they will be able to stay.” Some were more cautious: “Perhaps my children will benefit. The fishery already doesn’t allow us to make a living” (both respondents from Chamela). Respondents from San Mateo and Chamela agreed that “a lot of land has been bought by outsiders” (81% and 77% respectively). “They take over people’s land” or “it is an important income source but I don’t like our country being sold to foreigners”. When asked whether the new developers take part in political decision-making processes, only Chamela reported that the Zafiro development is making decisions in the community without consulting them (72%). When asked to select a feeling concerning the new projects, people of all three localities chose hope (64%) over indifference (18%) or anxiety (18%).

There were differences between localities in respondents’ specific interests in tourism development: for Francisco Villa and San Mateo; promoting community development, job creation for locals, and the opening of hotels were considered the most urgent. For Chamela respondents respect for local traditional activities and customs was considered the most relevant issue. Some respondents did not articulate their priorities, saying that they believed their concerns would not interest the developers. However the majority spoke passionately about their expectations and hopes in regard to employment and respect for local people. When asked to imagine the region and their villages without tourism, people gave diverse answers (note that categories were developed from responses to an open-ended question) and one respondent said “It would be good to have more employment, a strong source of employment. This would rise up everything. There are only so much temporary employments; we need a real big employment”. Another said: “tourists don’t visit the villages, they just lock themselves up”, indicating the perceived need to improve the urban image in order for the village to be interesting for tourists. They also commented that without tourism they would be “poor, without employment options, like it is now”. One person asked for “respect, let the poor do their work; we need liberty and access to the ocean”. One respondent from Chamela explained, “We don’t see anything good for the fishermen coming from tourism, but when there will be no fish any more, at least there would be tourism.”

5.6. Tourism and the Environment at Costalegre

There is an important conservation sector in Costalegre that is perceived in different ways by stakeholders. The long-term maintenance of ecosystems continues to be a great challenge and the role of tourism is still unknown. Coastal areas are complex, dynamic, and fragile, not least because they are the transition zone from marine to terrestrial ecosystems [54]. The coast in the La Huerta Municipality is an ecologically important site, and its ecosystems are maintained because of protected areas legislation. It is covered by dunes with coastal thickets and by tropical dry forest, one of the world’s most threatened ecosystems [55]. Conservationists involved in research and environmental conservation in the area have become an important stakeholder, and the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve (CCBR) in Costalegre, for example, is a critical site where environmental regulations play a significant role. Since 2007, the federal government has asked the reserve to be involved in reviewing the Environmental Impact Assessments, which are mandatory in all new tourism proposals. Initially the environmental conservation sector was successful in blocking some of the proposals due to the severe ecological impacts they were likely to have, especially regarding water management, which is a scarce resource [7,8]. However, several of these projects have since been granted permission to go ahead with construction (see Table 4). For tourism developers, the environmental conservation sector in the region is perceived in two contrasting ways. The first is as “conservationists with extreme opinions; people who do not want a single leaf to be moved”, with the result that “possible new developers prefer to invest elsewhere where no strong conservationist lobby exists”. However, the other perception is that the presence of the biosphere reserve means that ecosystems will be maintained and land will not be converted for agricultural use, which is of critical importance for the exclusive and environmentally friendly image most of high-end tourism and real estate projects seek to project.

Costalegre region has four environmental protection categories: “Priority Hydrological Region”, “Priority Terrestrial Area”, “Water Reserve Chamela” (national), and “Priority Eco-region Global 200” (international). La Manzanilla Estuary and the wetlands of the Biosphere Reserve are also Ramsar sites. Some beaches and islands are protected sanctuaries. Zafiro Nature Reserve, adjacent to the CCBR, is the newest voluntarily protected area, established by one of the bigger tourism developers who started building in 2012. However, we could not find any governmental agency involved. Conanp, Mexico’s official agency for all natural protected areas does not interfere with the CCBR [56]. According to the Regional Tourism Office Commissioner, the creation of local Ramsar boards has not been successful “because of the lack of interest of local actors”. Some turtle protection programs report their work to Conanp (i.e., Careyes Turtle Program). Most members of the tourism sector, the Mayor of La Huerta and the Jalisco State Environmental Secretary acknowledged AECA as the principal voice of the tourism developers.

6. Discussion

Our study documents and makes visible the views of people in different social groups who live in the area where we conducted our fieldwork in Costalegre. It shows how these groups have diverse lifestyles and interact in very different ways with the natural environment. Tourism is a key activity in Costalegre, yet there has been little research on governance there. This paper aims to contribute to an analysis of governance and to provide useful insights for future research. We intend that it serves as a baseline to stimulate processes of reflection and change.

6.1. Overwhelming Contrasts in Costalegre

Tropical coasts have seen an increase in tourism over the last 60 years [57], especially sun and beach tourism. One of the most important findings that emerged from our study of tourism in Costalegre is the extreme contrast of the worlds that exist in this particular area. In the same day, one can visit, or view from the sea, beautiful “private” beaches where wealthy families live in huge mansions, or conduct an interview in a small hotel in a rural town where people are generally involved in multiple economic activities in their struggle to cover their basic household needs. The contrast in lifestyles between rural towns and high-end tourism makes for a difficult scenario when it comes to constructing a regional governance strategy that is socially fair and takes into account the needs of the majority of its inhabitants.

Although Costalegre shares similar inequality problems with places such as Cancun, where large transnational tourist companies reap extraordinary profits and have had a huge impact on both the regional landscape and local lived realities [58], the situation is different. Throughout the last seven decades the Jalisco coast has been recognized as having great tourism potential and a series of large projects have been proposed, most of which have remained dreams on paper [6]. Its development is unique in Mexico because of the density of exclusive high-end tourism whereby a small and very wealthy sector has been able to buy large pieces of land along beautiful beaches, which they have made private, thus denying local residents access to their natural heritage. Although these high-end tourists live in the region for most of the year, local villagers see them as tourists who are usually also foreigners. They are known as residential tourists.

Local residents we spoke to talked of the struggles they endure to make a living. When asked about their perceptions of tourism in the area, some respondents said that they could see it provided some jobs and believed it had the potential to grow and provide employment and better incomes for them and their children. However, others disagreed that there were benefits to tourism, and were especially upset about the beaches being closed, particularly fishermen, because of the detrimental effect on their livelihoods. Others were of the opinion that access to water sources could become a severe problem in the future.

6.2. Tourism Governance in Costalegre

Mexico’s tourism plans and programs show goals, that apart from promoting investments, consider environmental protection and the inclusion of local communities for their social benefit (see Table 5). One of the most striking results of our work was that although for over 70 years Costalegre has been promoted as a tourism corridor important for the economic development of the Jalisco coast, the government authorities still do not know precisely what the region has to offer. The official numbers for tourism facilities and hotel beds differ greatly to ours and the government agencies that are actually conducting good work are isolated. The data they generate serves only to fill reports that seem to have little or no impact. A key example is Costalegre’s Regional Tourism Office, which conducts extensive and time consuming work registering and monitoring tourism facilities. According to its Commissioner, it does not have the mandate to force hotels and other tourism establishments to provide them with the information they need. Although this office could play a central role in gathering data and ensuring that existing regulations are complied with and that tourism stakeholders share information and offer an acceptable and consistent standard of service, they are restrained by the legal framework in which they operate. In this sense, the government is clearly inefficient in that it has offices gathering information, which is not used for the decision-making processes taking place at different institutional levels. Results also show that although several agencies exist operating at the different levels and all have written documents with social and environmental goals that would allow the transition from a state-centric to a society-centric mode of governance [59], this is not exactly what is happening. What our evidence reflects is that although the private sector is part of society, this sector has gained strong power and is capable of deeply influencing the decisions taken by government. This is not new, as Dredge and Whitford [60] note, that pre-existing institutional structures, policymaking processes, and underlying power structures determine outcomes in tourism governance.

It should also be emphasized that in Costalegre, the government has given priority to the maintenance and upgrading of infrastructure, such as widening the coastal road, as well as intensifying its advertising of the region as an important tourism destination. Its support for the owners of tourism facilities is differential. The small and medium sized hotels are not well organized and most do not communicate with the few regional agencies there are, because they do not perceive any use in them. Rather, some interviewees claimed they had been abandoned by governmental agencies. On the other hand, the wealthy private sector has its own organizations and receives government support from the federal to the municipal levels, not least through being given building permission for new facilities, and being allowed the right to restrict access to the beaches. The Association of Tourism Entrepreneurs of Costalegre (AECA) is acknowledged as having a strong presence and the power to negotiate and win government support. Most luxury hotels and real estate projects are members of AECA and use it as their mouthpiece and negotiator. While AECA seems to represent the tourism industry in Costalegre, its legitimacy, as well as its ability to include and represent all actors equally, is questionable. Indeed, its presence is not an indicator either of effective collaboration or adequate policy outcomes [61].

Although there is a strong perception among local rural people that the region is a tourist destination and that tourism is a source of employment (actual and potential), they do not see their own communities as being a part of this. They claim that their views are not taken into account. Some respondents argued that their way of life is not being respected, others viewed closing access to beaches as a huge problem, while others cited potential problems with water availability in the near future if more developments are built.

The involvement of conservationists and academics who have been present in the region for decades, in the decisions made regarding tourism, has only been sporadic. This sector was involved in the creation of the Biosphere Reserve and more recently was asked to assess environmental impact assessments of new tourism developments presented by investors to governmental authorities. Although some researchers make the effort to communicate their work to the local population (rural families, local schools, and tourism entrepreneurs and employees), these efforts have also been sporadic and have had little impact.

This situation has resulted in a complex scenario that highlights the ineffective governance system in Costalegre. Decision-making processes are neither efficient nor effective. Indeed, they enable the wealthy private sector that includes foreign families but also Mexican politicians (some ex-governors) who have political connections and are therefore able to be supported by government authorities at different institutional levels, to reinforce a model where a few groups of individuals wield all the power and are able to achieve their goals at the expense of other sectors of society [13]. It should also be taking into account that although the Costalegre region includes four municipalities, the type of tourism development that has taken place in the coastal area of La Huerta (see Figure 1) where our case study takes place, is a small area that is also isolated. The municipality’s offices are not close and their agents in the localities attend issues related to primary production activities such as agriculture and livestock but not tourism, least the so-called high-end tourism. Also and according to the mayor interviewed at the time, it is in the interest of the municipality to support them. According to the Regional Tourism Office, they do not provide the information required by them. These examples show the power they have over government as results have shown and can explain the lack of a proper governance notion that seeks to move towards more inclusive decision making processes and ways of building agreements across all layers of society, creating platforms for negotiation that are not only in the hands of government but are shared among stakeholders [20]. If their interaction with the local inhabitants, which is mostly reduced to having them as cleaning, cooking or driver employees, is considered as well, the case study presents itself as one of ineffective governance.

6.3. Challenges for Regional Governance in Costalegre

To change the balance of power among stakeholders would require a mediation process [62,63], not only to raise awareness within the private sector, which seems difficult to achieve, but also to constrain their influential role in decision making [64,65]. At the same time, bottom up processes that allow local rural people to defend their rights need to be strengthened. To regain access to beaches in the region is a clear example that needs to be addressed, particularly as several fishing cooperatives have been expelled from beaches, infringing on their basic right to earn a living. The right for everyone to enjoy the beaches, including local families, should also be respected. Indeed, under Mexican law beaches are common public assets [66]. Deeper discussions among stakeholders are needed about how to make decision-making processes inclusive and efficient, as well as socially just and legitimate [67]. Yet, according to Haugland [68] a tourist destination should be seen as a network whose success is dependent upon the performance of its interacting actors. The challenge is in the complexity of the multilevel networks that need to be incorporated into an overall decision-making framework, going beyond the definition of common goals and increasing participation [61].

In order to contribute to the strengthening of a tourism governance model that allows continuous interactions and negotiations among stakeholders, as well as the mitigation or solution of conflicts [69], we identified the following recommendations: A top priority that emerges from our study is the need for an urgent commitment from the authorities to give Costalegre’s Regional Tourism Office more executive mandates. This agency and its personnel should play a more central role and become the much needed link between government plans and the needs of all inhabitants, enabling them also to rein in the overwhelming power that the wealthy private sector has in the region. The capacity of the Municipality of La Huerta also needs to be strengthened, particularly in its role as a broker among all the tourism stakeholders. The municipality should be in a position to secure the wellbeing of all residents, mitigating and solving problems such as the closure of beaches by wealthy landowners and investors, which has had a highly detrimental impact on fishing communities and local residents. It should also become more involved in environmental conservation issues, rather than leaving these to the owners of private nature reserves or to the conservation sector [56]. This may seem an impossible task since, for many years now, municipalities in Mexico have been losing power and the capacity to deal with powerful sectors such as private investors. At the time of our fieldwork, they were also struggling with a severe lack of financial support [70].

6.4. The Role of Environmental Scientists and Conservationists

For more than 45 years, biologists and other academics have been conducting research in the Costalegre region. In the last 12 years, they have played a role in analyzing new tourism proposals for the environmental authorities. They have demonstrated how some proposals were severely flawed, containing multiple errors regarding the scientific data, and that they should therefore not be used as documents on which decisions regarding tourism development are made. Their expert opinion reports were endorsed by the National Commission of Protected Areas (Conanp) and, in 2007, they even played an active role in communicating to the public, through the national and international press, that these projects should not be accepted because they constitute a severe threat to the wellbeing of Costalegre’s social-ecological system. However, due to the political power and economic capacity that the private entrepreneurs enjoy, the projects were eventually approved. The academic sector and the individual researchers (as members of public institutions) should accept that they have an important role to play in the route that Costalegre takes in the near and long-term future. This role becomes even more critical given the climate change scenarios that Costalegre is likely to face. The conservation of the environmental services of coastal ecosystems (wetlands, beaches and dunes) is fundamental for the protection of local people and also for hotel infrastructure, particularly given that hurricanes which severely affect the coast are becoming more frequent in the region (the last ones were in 2011 and 2015). Academic expertise should be taken into account in decision-making processes which impact on the integrated social-ecological system. Scientists should not work in isolation: they should play an active role in contributing to the understanding of the severe crises that humanity faces today, and have an important role to play in working towards the construction of sustainable paths of socio-economic development that recognize our strong dependence on healthy ecosystems [71].

7. Conclusions

According to Becker [72] tourism has been an important industry at least since the 1960s and has grown rapidly in the last few years so that developing countries now view it as a vital source of income. However, the failure of tourism to stimulate local economies, advance environmental conservation or respect local cultures has highlighted the negative impacts of tourism in countries such as Spain [73], Argentina [74], and other parts of Mexico [75]. Our case study adds to the list of places where an alternative model of tourism governance is urgently needed. We can conclude that at the Costalegre there has been a long desire (since the 1950s) to transform the region into a successful endeavor that could bring economic benefits to the Jalisco coast. However, economic benefits have only been obtained by a very small fraction of people concentrated in the middle part of the municipality of La Huerta, who have invested in luxury and high-end hotels, mansions to rent or for receiving guests. The scenario is one of highly contrasts where unequal situations prevail among the inhabitants. In terms of the dimensions involved in tourism governance, a wide range of government documents exist aimed at guiding the development of tourism towards a sustainable form (considering issues of social participation and justice, as well as maintenance of ecological processes). However, the reality does not correspond to the objectives and plans written in official papers. The local state and municipal authorities related to tourism do not have the mandate or the capacities that they would need to perform a more efficient role that could mitigate the socio-economic differences and prevent environmental effects. The strong dominance of a wealthy private sector controlling decision making processes and the absence of a strong and organized civil society act as deterrents and do not correspond to current notions and ideals of effective sustainable governance. At present, there are many challenges to be overcome for the construction of a platform of dialogue and negotiation. Nevertheless, we believe that regional and local actors, as well as the academic and conservation sectors, need to play a committed role in the necessary long-term goal toward sustainability, maintaining ecosystems while also sharing the benefits of tourism more equitably among the people of Costalegre.

Author Contributions

A.C. and M.R. conceived the study, established the study’s research questions and designed the methodology. M.R. collected and analyzed most of the data. With E.G.-F., the conceptual framework was constructed. He, P.M.-C. and C.T.-D. assessed and reviewed the whole research process. A.C. acquired funding and edited the entire manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico UNAM (PAPIIT IN300813) and the first author is thankful to Conacyt for the PhD scholarship.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all the people interviewed and surveyed who kindly gave us their time and shared their knowledge, opinions, and ideas. Special thanks to Jorge H. Vega, executive chief of the Chamela Biological Research Station of UNAM and to Azucena Cedeño, Randall Chávez, Regina González, Ana Leal, Lucía Martínez, Ricardo Martínez, Coral Mascote, Francisco Mora, Sofía Monroy, Gabriela Romo, and Jésus Verduzco for their assistance during fieldwork, Miriam Linares for the elaboration of figures, Karla Tapia for editing the references and Sarah Bologna for English editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNWTO. Tourism Highlights, 2017 ed.; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Challenger, A. Utilización y Conservación de los Ecosistemas Terrestres de México: Pasado, Presente y Futuro; UNAM, Instituto de Biología: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, G.; García, A. Conserving Neotropical Biodiversity: The Role of Dry Forests in Western Mexico. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, I.; Dirzo, R. Deforestation of seasonally dry tropical forest: A national and local analysis in Mexico. Biol. Conserv. 2000, 94, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Godínez, C.; Schroeder, N.; Galicia, C.; Pujadas-Botey, A.; Martínez, L. El bosque tropical seco en riesgo: Conflictos entre uso agropecuario, desarrollo turístico y provisión de servicios ecosistémicos en la Costa de Jalisco, México. Interciencia 2009, 34, 844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Tello-Díaz, C. La Transformación del Paisaje: Colonización, Desarrollo y Conservación de la Costalegre de Jalisco, en la Región de Cuixmala y Careyes (1943–1993); Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, A.; Domínguez, C.; García, A.; Quesada, M.; Vega, J. Proyectos de desarrollo turísticos “La Huerta” (Clave: 14JA2006T0018[Marina Careyes]) y “Tambora” (Clave: 14JA20-06T0011) en áreas vecinas a la Reserva de la Biósfera de Chamela-Cuixmala. Unpublished technical report. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boege, K.; Castillo, A.; García, A.; Miranda, A.; Rueda, R.; Ruiz, A.; Vega, J.; Trejo, I. Dictamen técnico de la manifestación de impacto ambiental del proyecto de desarrollo turístico “Zafiro” (clave: 14ja2009t0017): Identificación de posibles impactos a las áreas naturales protegidas de la región. Com. Técnico Asesor la Reserv. la Biósfera Chamela-Cuixmala, Univ. Nac. Autónoma México, Fund. Ecológica Cuixmala, A.C. Unpublished Technical report. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fasenfest, D. Government, governing, and governance. Crit. Sociol. 2010, 36, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, L.F. Gobernanza: El nuevo Proceso de Gobernar; Fundación Friedrich Naumann para la Libertad: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010; ISBN 978-607-95144-2-6. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, P.; Pattberg, P.; Schroeder, H. Multiactor governance and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Camargo, B.A. Tourism governance and policy: Whither justice? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, L.; Job, H. Challenges to actor-oriented environmental governance: Examples from three mexican biosphere reserves. Tijdschr Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2012, 103, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, M. Drivers of change in regional tourism governance: A case analysis of the influence of the New South Wales Government, Australia, 2007–2013. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 990–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J. New governance, new democracy? QoG Work. Pap. Ser. 2009, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vatn, A. Environmental governance—From public to private? Ecol Econ. 2018, 148, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: From first- and second-order to third-order change? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, G. Governance as theory: Five propositions. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1998, 50, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainability science: A review, an analysis and some empirical lessons. Environ. Conserv. C Found. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. Policy networks and the local organisation of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, N.; Dredge, D. Local tourism governance: A comparison of three network approaches. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, F.; Dredge, D.; Lohmann, G. Leadership and governance in regional tourism. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, L. Gobernanza ambiental, actores sociales y conflictos en las áreas naturales protegidas mexicanas. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 2010, 72, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R. Governance and Sustainable Tourism: What is the Role of Trust, Power and Social Capital? J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.; Parra, F.; Blancas, J. Evolution of humans and by humans. In Evolutionary Ethnobiology; Albuquerque, U.P., Muniz de Medeiros, P., Casas, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 21–34. ISBN 978-3-319-19917-7. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hufty, M. Investigating Policy Processes: The Governance Analytical Framework (GAF). In Research for Sustainable. Development: Foundations, Experiences, and Perspectives; Wiesmann, U., Hurni, H., Eds.; Geographica Barnesia: Bern, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 6, pp. 403–424. ISBN 978-3-905835-31-1. [Google Scholar]

- DOF (Diario Oficial de la Federación). Declaratoria de Zona de Desarrollo Turístico Prioritario, del corredor turístico ecológico denominado Costalegre, en el Estado de Jalisco, con superficie de 577.2 hectáreas. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 1990. Available online: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4692300&fecha=05/12/1990 (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- SIEG. La Huerta. 2010. Available online: http://www.sieg.gob.mx (accessed on 1 January 2016).

- INEGI. Cuéntame. 2015. Available online: http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/monografias/informacion/jal/poblacion/ (accessed on 12 February 2017).

- Warman, A. El Campo mexicano en el Siglo XX; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001; ISBN 9789681663292. [Google Scholar]

- CEURA. Programa Subregional de Desarrollo Turístico Costalegre, Estado de Jalisco. Capítulo 02 Diagnóstico Integral. Guadalajara. Unpublished Technical Report. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. La costa de Jalisco: Una Región Abierta al Esfuerzo de Jalisco y México; Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco: Guadalajara, Mexico, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Tello-Díaz, C. Los Señores de la Costa; Grijalbo: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014; ISBN 9786073122580. [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Diaz, M.A. Socio-demographic impacts of residential tourism: A case study of Torrevieja, Spain. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, F.A.; Vega-Rivera, J.H.; García-Aldrete, A.N. Introducción. In Historia Natural de Chamela; Noguera, F.A., Vega-Rivera, J.H., García-Aldrete, A.N., Quesada-Avendaño, M., Eds.; Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2002; pp. xv–xxi. ISBN 970-32-0520-8. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, A.; Magaña, A.; Pujadas, A.; Martínez, L.; Godínez, C. Understanding the interaction of rural people with ecosystems: A case study in a tropical dry forest of Mexico. Ecosystems 2005, 8, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Szekely, A.; García, A.; Rodríguez, P.; Noguera, F. Programa de Manejo de la Reserva de la Biosfera Chamela-Cuixamala; Instituto Nacional de Ecología, SEMARNAP: Mexico City, Mexico, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Balvanera, P.; Daw, T.M.; Gardner, T.A.; Martín-López, B.; Nostrom, A.; Speranza, C.; Spierenburg, M.; Bennett, E.; Farfan, M.; Hamann, M.; et al. Key features for more successful place-based sustainability research on social-ecological systems: A programme on ecosystem change and society (PECS) perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social y Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. ISBN 0-7619-2073-0. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a los Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 0521338069. [Google Scholar]

- Newing, H. Conducting Research in Conservation: Social Science Methods and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-415-45792-7. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.iies.unam.mx/laboratorios/socioecologia-comunicacion-sustentabilidad/vinculacion-social/talleres/ (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- Coates, K.S.; Healy, R.; Morrison, W.R. Tracking the Snowbirds: Seasonal Migration from Tracking the Snowbirds. Am. Rev. Can. Stud. 2002, 32, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiernaux-Nicolas, D. La promoción inmobiliaria y el turismo residencial: El caso mexicano. Scr. Nov. 2005, IX, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fonatur. Programa Subregional de Desarrollo Turístico Costalegre, Estado de Jalisco, D.F., México, 2011. Available online: https://secturjal.jalisco.gob.mx/sites/secturjal.jalisco.gob.mx/files/u16/08_costalegre_presentacion_ejecutiva.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- Sectur. Programa de Turismo Sustentable en México. México, 2011. Available online: http://www.sectur.gob.mx/pdf/planeacion_estrategica/PTSM.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- Moreno-Casasola, P. La zona costera y sus ecosistemas. In Servicios Ecosistémicos de las Selvas y Bosques Costeros de Veracruz; Moreno-Casasola, P., Ed.; INECOL, ITTO, CONAFOR, INECC: Xalapa, Mexico, 2016; pp. 18–36. ISBN 978-607-7579-57-1. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen, D. Tropical dry forests. In Biodiversity; Wilson, E.O., Peter, F.M., Eds.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 130–137. ISBN 0-309-03739-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pujadas, A.; Castillo, A. Social Participation in Conservation Efforts: A Case Study of a Biosphere Reserve on Private Lands in Mexico. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: The end of the last frontier? Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2001, 44, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.M.; Momsen, J.D. Gringolandia: The construction of a new tourist space in Mexico. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Sauer, A.; Bornemann, B.; Burger, P. Governing Towards Sustainability—Conceptualizing Modes of Governance. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Whitford, M. Event tourism governance and the public sphere. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Bramwell, B. Political economy and the emergence of a hybrid mode of governance of tourism planning. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauert, J.; Zadek, S. Introducción: El arte de la mediación: Construyendo políticas desde las bases. In Mediación para la Sustentabilidad. Construyendo Políticas Desde las Bases; Zadek, S., Blauert, J., Eds.; Plaza y Valdés Editores, The British Council, IDS Sussex, CIESAS: Mexico City, Mexico, 1999; pp. 1–22. ISBN 968-856-639-X. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Getz, D. Community Roundtables for Tourism-related Conflicts: The Dialectics of Consensus and Process Structures. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 290–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-García, P.; Luna-Sánchez, E. The Environmentalism of the Rich and the Privatization of Nature: High-End Tourism on the Mexican Coast. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2012, 39, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, C.A.H. Privatización y despojo de territorios costeros en el estado de Jalisco. La barbarie del turismo en el Rebalsito de Apazulco y la bahía de Tenacatita. In El México Bárbaro del siglo XXI; Rodríguez, C., Cruz, R., Eds.; UAM-X, UAS: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013; pp. 331–363. ISBN 9786072801172. [Google Scholar]

- DOF (Diario Oficial de la Federación). Ley General de Bienes Nacionales. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2007. Available online: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4999489&fecha=31/08/2007 (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Fairbrass, J.; Jordan, A.; Paavola, J.; Rosendo, S.; Seyfang, G. Governance for sustainability: Towards a “thick” analysis of environmental decision making. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, S.A.; Ness, H.; Grønseth, B.-O.; Aarstad, J. Development of tourism destinations: An Integrated Multilevel Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, C.; Van den Ban, A. Communication for Rural Innovation. Rethinking Agricultural Extensión; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz-porras, A.; García-Vázquez, N. La planeación de transferencias hacia los municipios jalisciences: Principios de equidad y no discriminación. Econ. Soc. Territ. 2014, XIV, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubchenco, J. Entering the century of the environment: A new social contract for science. Science 1998, 279, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E. The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jurdao, A. Los Mitos del Turismo; Endymion: Madrid, Spain, 1992; ISBN 84-7731-132-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kopecek, J. Turismo y pobreza: Una aproximación a los modelos de desarrollo turístico. In Turismo y Desarrollo Crecimiento y Pobreza; Arnaiz, S.M., Dachary, A.C., Eds.; Universidad de Guadalajara: Jalisco, Mexico, 2008; pp. 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Casasola, P. Veracruz: Mar de arena; Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz; Secretaría de Educación del Estado de Veracruz: Veracruz, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).