Trusting/Distrusting Auditors’ Opinions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Trust, Trustworthiness and the Going Concern Opinion

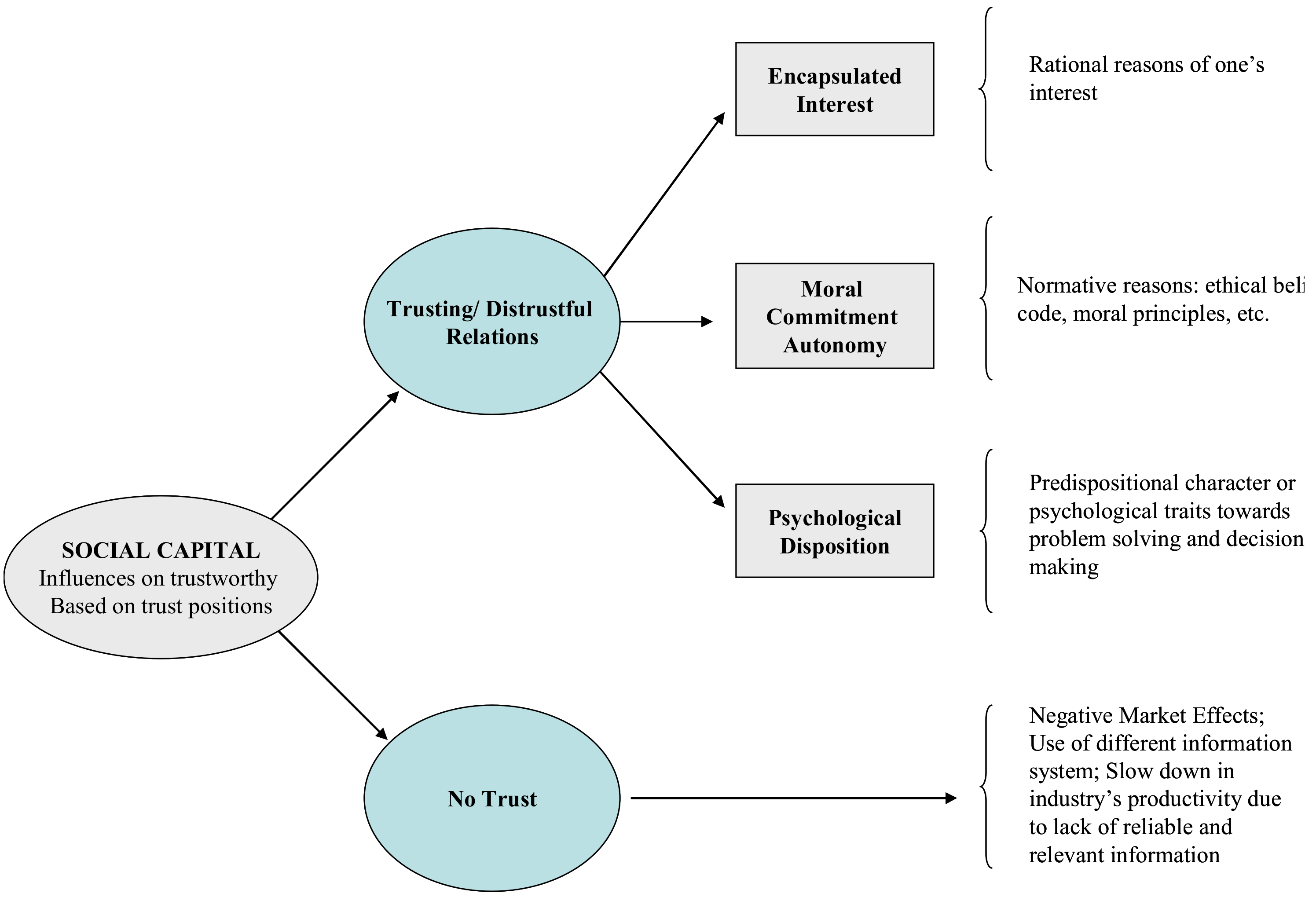

2.1. Social Capital and Trust

2.2. Auditors’ Going Concern Opinions

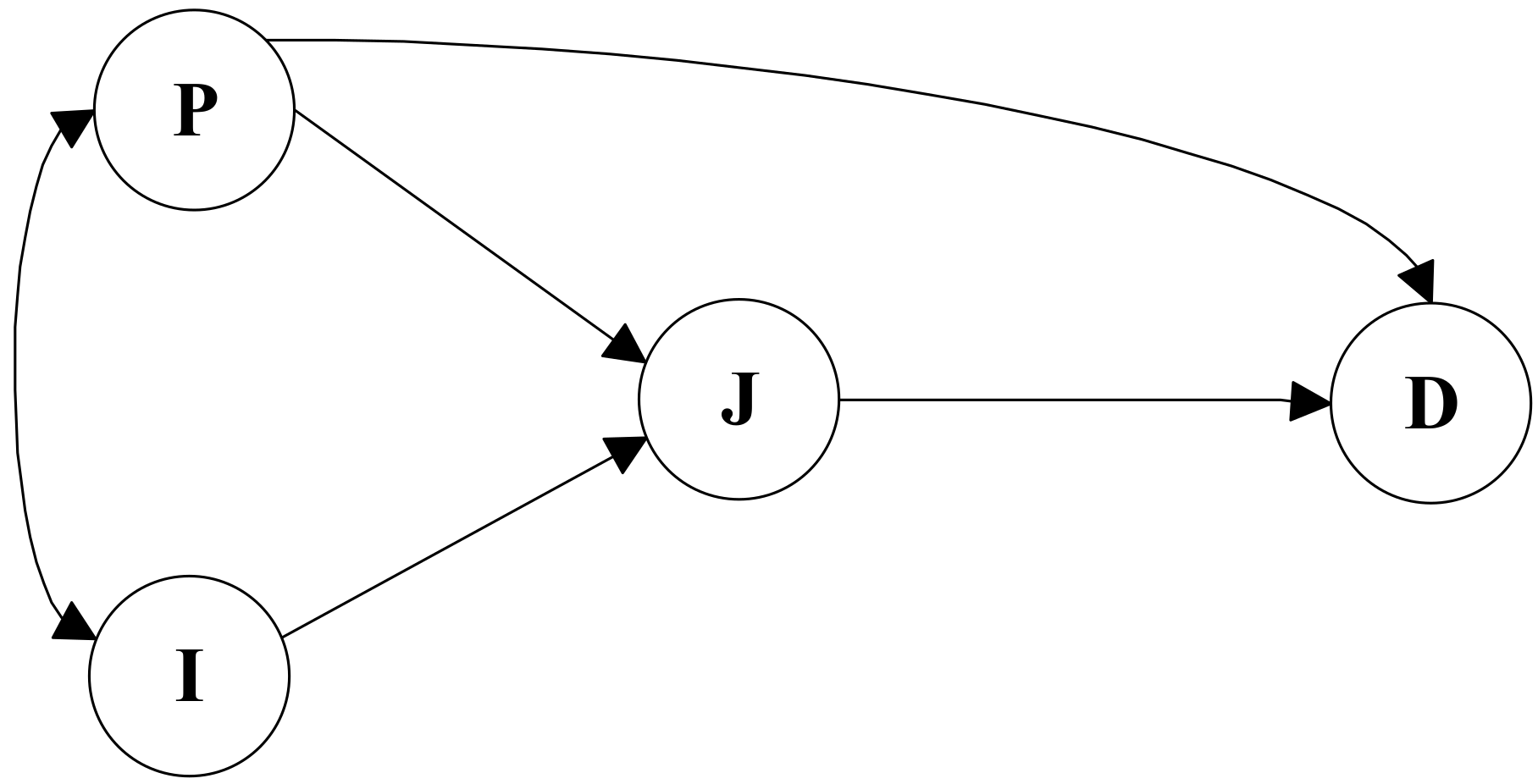

3. The Throughput Conceptual Model

4. Six Dominant Trust Pathways

5. Illustrating Six Trust Pathways: The Case of the Auditors’ Going Concern Opinion

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodgers, W. Knowledge Creation: Going Beyond Published Financial Information; Nova Publication: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Definitions and Selected Aspects of Measuring and Improving Social Capital in Organisations. In Social Aspect of Market Economy; Jeżak, P., Ed.; AJD: Częstochowa, Poland, 2011; pp. 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duska, R.; Duska, B. Accounting Ethics; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guiral, A.; Rodgers, W.; Ruiz, E.; Gonzalo, J.A. Ethical dilemmas in auditing: Dishonesty or unintentional bias? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Guiral, A.; Gonzalo, J.A. Different pathways that suggest whether auditors’ going concern opinions are ethically based. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; McAllister, D.J.; Bies, R.J. Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 23, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, D.W.; Zenger, T.R. What is a relationship worth? Repeated exchange and the development and deployment of relational capital. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.E.; Schweitzer, M.E. Prosocial lies: When deception breeds trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proc. 2015, 126, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhe, A.; Miller, S.R. The structure of optimal trust: A comment and some extensions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, F.; Solomon, R. Creating trust. Bus. Ethics Q. 1998, 8, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarocas, C. The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater, J.; Sierra, C. Review on computational trust and reputation models. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2005, 24, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.V.; Walsham, G. Reconceptualizing and managing reputation risk in the knowledge economy: Toward reputable action. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. The role of the audit committee, the internal auditor and the statutory auditor as the bodies supporting effective corporate governance in banks. Finanse Rynki Ubezpieczenia 2011, 38, 885–897. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. The role and tasks of the Internal Audit and Audit Committee as bodies supporting effective Corporate Governance in ensurance Sector Institutions in Poland. Oeconomia Copernicana 2012, 4, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.J.; Parker, S.; Peters, G. The effects of post-bankruptcy financing on going concern reporting. Adv. Account. 2003, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W. Throughput Modeling: Financial Information Used by Decision Makers; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, W. E-Commerce and Biometric Issues Addressed in a Throughput Model; Nova Publication: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.M. Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horizons 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P.; Mullen, M.R. Understanding the influence of national culture on the development of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, G.; Palmon, D. A negotiation-oriented model of auditor-client relationships. Group Decis. Negot. 2000, 9, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioukas, C.S.; Reuer, J.J. Isolating trust outcomes from exchange relationships: Social exchange and learning benefits of prior ties in alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1826–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvily, B.; Zaheer, A.; Kamal, D.F. Mutual and exclusive: Dyadic sources of trust in interorganizational exchange. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrowe, R.T.; Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Kramer, M.L. Social networks and the performance of individuals and groups. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 316–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetta, D. Mafia: The Price of Distrust. In Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations; Gambetta, D., Ed.; Basil Bernstein: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 154–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, L.V.; Buchholtz, A.K. Trust, risk, and shareholder decision making: An investor perspective on corporate governance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2001, 11, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, R. The Evolution of Cooperation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.H.; Ferrin, D.L.; Cooper, C.D.; Dirks, K.T. Removing the shadow of suspicion: The effects of apology versus denial for repairing competence-versus integrity-based trust violation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Trust and Power; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, R. Trust and Trustworthiness; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Werner, J.M. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duska, R. The good auditor-skeptic or wealth accumulator? Ethical lessons learned from the Arthur Andersen debacle. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 57, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P. The auditors’ going concern decision and types I and II errors: The Coase theorem, transaction costs, bargaining power and attempts to mislead. J. Account. Public Policy 2004, 23, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Chan, L. Are Auditors Professionally Skeptical? Evidence from Auditors’ Going-Concern Opinions and Management Earnings Forecasts. J. Account. Res. 2014, 52, 1061–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W. The effects of accounting information on individuals’ perceptual processes. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 1992, 7, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W. The influences of conflicting information on novices’ and loan officers’ actions. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Gago, S. A model capturing ethics and executive compensation. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 48, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Gago, S. Stakeholder influence on corporate strategies over time. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Söderbom, A.; Guiral, A. Corporate social responsibility enhanced control systems reducing the likelihood of fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 185, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Housel, T.J. The effects of environmental risk information on auditors’ decisions about prospective financial statements. Eur. Account. Rev. 2004, 13, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiral, A.; Rodgers, W.; Ruiz, E.; Gonzalo, J.A. Can expertise mitigate auditors’ unintentional biases? J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2015, 24, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, K.; Rodgers, W. Enhancing information usefulness by line managers’ involvement in cross-unit activities. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 683–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, A.; Rodgers, W. Improving managerial effectiveness in the workplace: The case of sexual harassment of navy women. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 27, 1953–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, A.C.; Berman, S.L.; Jones, T.M. The structure of optimal trust: Moral and strategic implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, J.M. International Reporting: The Way Forward. International Federation of Accountants. Available online: http://www.ifac.org/MediaCenter/?q=node/view/296 (accessed on 24 July 2007).

- Rodgers, W. Process Thinking: Six Pathways to Successful Decision Making; iUniverse, Inc.: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Currall, S.C.; Epstein, M.J. The Fragility of organizational trust: Lessons from the rise and fall of Enron. Organ. Dyn. 2003, 32, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, L.T. Trust: The connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, R. Trusting Persons, Trusting Institutions. In Strategy and Choice; Zechhauser, R.J., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J.; Siegel, P. Understanding the Interaction Between Procedural and Distributive Justice. In Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research; Kramer, R.M., Tyler, T.R., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 16–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hummels, H.; Roosendaal, H.E. Trust in scientific publishing. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Dore, R. Taking Japan Seriously; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Good, D. Individuals, Interpersonal Relations, and Trust. In Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations; Gambetta, D., Ed.; Basil Bernstein: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. In Group Favoritism: The Subtle Side of Intergroup Discrimination. In Codes of Conduct: Behavioral Research and Business Ethics; Messick, D.M., Tenbrunsel, A., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.W.; Dimaggio, P.J. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Labianca, G.; Brass, D.J.; Gray, B. Social networks and perceptions of intergroup conflict: The role of negative relationships and third parties. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Bowie, N.E. (Eds.) Ethical Theory and Business; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.; Gunz, S.; McCutheon, J. Private/public interest and the enforcement of a code of professional conduct. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Administrative Behavior; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R.; Degoey, P. Trust in Organizational Authorities: The Influence of Motive Attributions on Willingness to Accept Decisions. In Trust in Organizations; Kramer, R.M., Tyler, T.R., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 331–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bradach, J.L.; Eccles, R.G. Price, authority, and trust: From ideal types to plural forms. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1989, 15, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, L.; Allwood, C.M. Managers’ Strategic Decision Processes in Large Organizations. In Decision Making: Social and Creative Dimensions; Allwood, C.M., Selart, M., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.W. Neither Market nor Hierarchy: Network Forms of Organization. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1990; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kornish, L.J.; Levine, C.B. Discipline with common agency: The case of audit and non-audit services. Account. Rev. 2004, 79, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, E.; Gómez Aguilar, N.; Fuentes-Barbera, C.; García Benau, M.A. Audit quality and the going-concern decision making process: Spanish evidence. Eur. Account. Rev. 2004, 13, 597–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiral-Contreras, A.; Gonzalo-Angulo, J.A.; Rodgers, W. Information content and recency effect of the audit report in loan rating decisions. Account. Financ. 2007, 47, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiral, A.; Ruiz, E.; Choi, H. Audit report information content and the provision of non-audit services: Evidence from Spanish lending decisions. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2014, 23, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M.; Raghunandan, K.; Subramanyam, K. Do non-audit service fees impair auditor independence? Evidence from going concern audit opinions. J. Account. Res. 2002, 40, 1247–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, S.A.; Williams, P.F. The philosophy and rhetoric of auditor independence concepts. Bus. Ethics Q. 2004, 14, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, L. Auditor size and audit quality. J. Account. Econ. 1981, 3, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstraelen, A. Auditor economic incentives and going-concern opinions in a limited litigious continental European business environment: Empirical evidence from Belgium. Account. Bus. Res. 2002, 32, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, J. Auditor switching and conservatism. Account. Rev. 1994, 69, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, J.; Stephens, R.G. Evidence on opinion shopping from audit opinion conservatism. J. Account. Public Policy 1995, 14, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayachi, K.; Watabe, M. Restoring trustworthiness after adverse events: The signaling effects of voluntary “Hostage Posting” on trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proc. 2005, 97, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Roth, N.L. Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic “remedies” for trust/distrust. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.A.; Tetlock, P.E.; Tanlu, L.; Bazerman, M.H. Conflicts of interest and the case of auditor independence: Moral seduction and strategic issue cycling. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Moore, D.A.; Tetlock, P.E.; Tanlu, L. Reply. Reports of solving the conflicts of interest in auditing are highly exaggerated. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’clock, P.; Devine, K. An investigation of framing and firm size on the auditor’s going concern decision. Account. Bus. Res. 1995, 25, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Li, S.X.; Prakash, R.; Deephouse, D.L. Reputation, diversification and organizational explanations of performance in professional service firms. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, J.R. Why press coverage of a client influences the audit opinion. J. Account. Res. 2003, 41, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, C.A. Loss contingency reports and stock prices: A replication of Banks and Kinney. J. Account. Res. 1991, 29, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiral, A.; Ruiz, E.; Rodgers, W. To what extent are auditors’ attitudes toward the evidence influenced by the self-fulfilling prophecy? Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, D.; Taffler, R. Ethical behaviour in the UK audit profession: The case of the self-fulfilling prophecy under going-concern uncertainties. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F. The information content of the auditor’s going concern evaluation. J. Account. Public Policy 1996, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, C.A. Uncertainty-modified audit reports and future earnings. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 1994, 13, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.E.; Williams, D.D. Do going concern audit reports protect auditors from litigation? A simultaneous equations approach. Account. Rev. 2013, 88, 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulanski, G.; Cappetta, R.; Jensen, R.J. When and how trustworthiness matters: Knowledge transfer and the moderating effect of causal ambiguity. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, D. Transforming our students: Teaching business ethics post-Enron. Bus. Ethics Q. 2005, 15, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W. Trust Relationships Viewed from a Throughput Modeling Approach; Nova Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.N.; Myers, L.A.; Omer, T.C. Exploring the Term of the Auditor-Client Relationship and the Quality of Earnings: A Case for Mandatory Auditor Rotation? Account. Rev. 2003, 78, 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerni, M.; Haapamäki, E.; Järvinen, T.; Niemi, L. Do joint audits improve audit quality? Evidence form voluntary joint audits. Eur. Account. Rev. 2012, 21, 731–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audit Analytics. PCAOB Member Updates Internal Control Analysis. 2016. Available online: http://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/pcaob-member-updates-internal-control-analysis/ (accessed on 27 February 2019).

| # | Trust Position | Pathway | Type | Social Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Trust as a rational choice | P → D | primary | Encapsulated interest |

| (2) | Rule-based trust | P → J → D | primary | Moral Commitment Autonomy |

| (3) | Category-based trust | I → J → D | primary | Psychological Disposition |

| (4) | Third parties as conduits of trust | I → P → D | secondary | Psychological Disposition/Encapsulated interest |

| (5) | Role-based trust | P → I → J → D | secondary | Psychological Disposition |

| (6) | History-based/dispositional trust | I → P → J → D | secondary | Psychological Disposition/Moral Commitment Autonomy |

| Position | Trustworthiness Level | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| As a rational choice (P → D) (Encapsulated interest) | Trust | Investors and stakeholders see auditors as expert “agents” contributing to minimize expected losses or maximize expected gains in their transactions, whereby the issuance of a warning signal is interpreted as protecting investors and stakeholders’ interests |

|

| Distrust | Investors and stakeholders may perceive that auditors have strong economic incentives to avoid the issuance of a warning signal. Thus, they distrust auditors’ clean opinions on the ability of their clients to continue in existence |

| |

| Rule-based (P → J → D) (Moral Commitment Autonomy) | Trust | Investors and other stakeholders may see the auditing profession as ethical exemplary due to a rigorous normative rule or legal system function in force. Also, the auditing profession may be viewed as a self-correcting profession which has positively reacted after the Enron-Arthur Andersen episode and other recent financial scandals |

|

| Distrust | Investors and other stakeholders perceive that the weak current legal system leads them to highly distrust auditors’ opinions (i.e., strategy issue cycling theory) |

| |

| Category-based (I → J → D) (Psychological Disposition) | Trust | Investors and other stakeholders highly trust auditors’ opinions from international accounting firms |

|

| Distrust | Investors and other stakeholders tend to distrust auditors’ opinions issued by small auditing firms. |

| |

| Third parties as conduits of trust (I → P → D) (Psychological Disposition/Encapsulated interest) | Trust | Investors and other stakeholders highly trust auditors’ opinions when media reports support their clients’ financial (either healthy or distressed) status |

|

| Distrust | Investors and stakeholders highly distrust on auditors involved in financial scandals and corruption cases |

| |

| Role-based (P → I → J → D) (Psychological Disposition) | Trust | Investors and stakeholders may perceive auditors’ decision to issue a clean audit opinion for a financially distressed client might be seen as a trustworthy behavior if the auditor takes into account the environmental conditions that affect client’s ability to survive. |

|

| Distrust | Investors and stakeholders may perceive an auditor’s decision to issue a going concern opinion (clean opinion) for a financially distressed client, such as untrustworthy behavior under a high (low) risk exposure auditing environment |

| |

| History-based and/or dispositional (I → P → J → D) (Psychological Disposition/Moral Commitment Autonomy) | Trust | Investors and stakeholders may trust a clean audit opinion (warning signal) for a financially distressed client might as a trustworthy behavior if they perceive that available information dominates auditors’ decision |

|

| Distrust | Investors and stakeholders may perceive a clean audit opinion for a financially distressed client as an untrustworthy behavior if they perceive that auditors’ decision may be unconsciously biased when processing independent information (e.g., Bazerman et al.’s moral seduction theory [79]) |

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodgers, W.; Guiral, A.; Gonzalo, J.A. Trusting/Distrusting Auditors’ Opinions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061666

Rodgers W, Guiral A, Gonzalo JA. Trusting/Distrusting Auditors’ Opinions. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061666

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodgers, Waymond, Andrés Guiral, and José A. Gonzalo. 2019. "Trusting/Distrusting Auditors’ Opinions" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061666

APA StyleRodgers, W., Guiral, A., & Gonzalo, J. A. (2019). Trusting/Distrusting Auditors’ Opinions. Sustainability, 11(6), 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061666