Research Topics in Accounting Fraud in the 21st Century: A State of the Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Accounting Fraud: A General Vision

3. Methodology of the Review

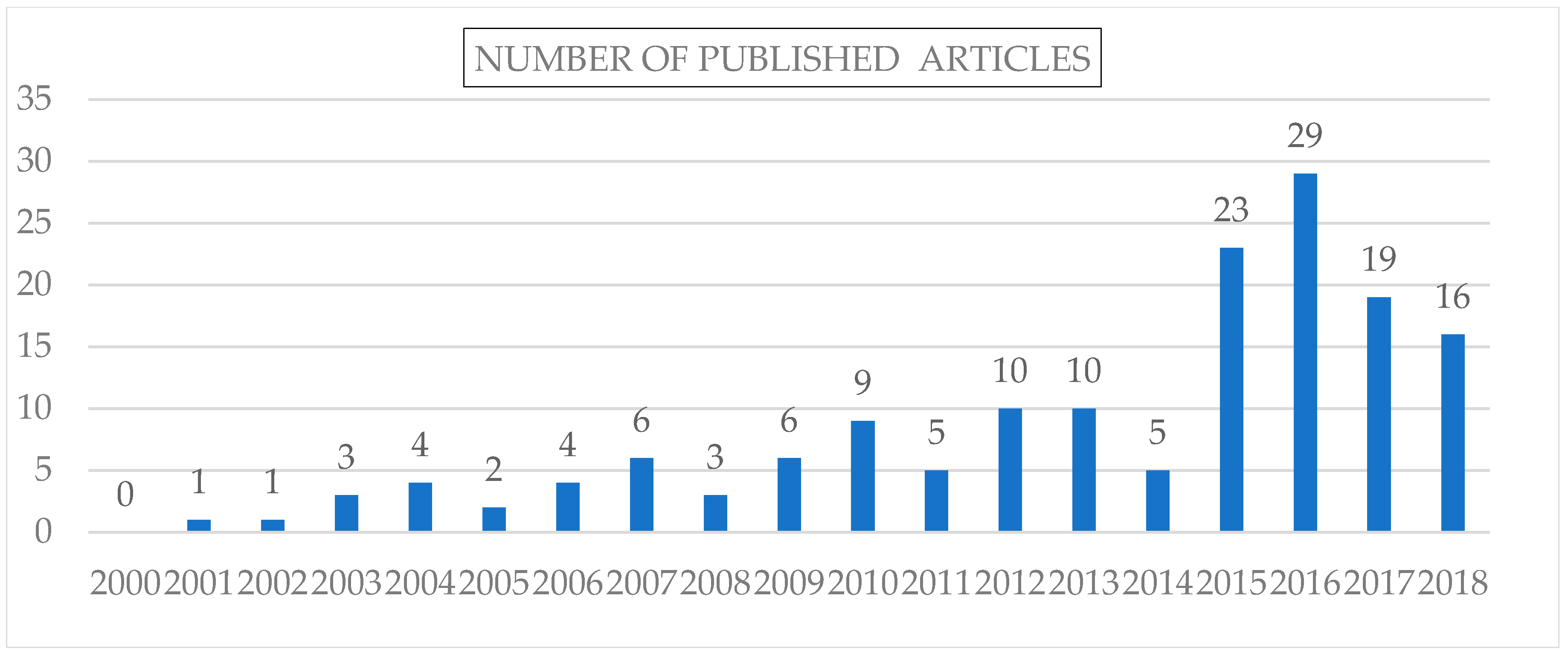

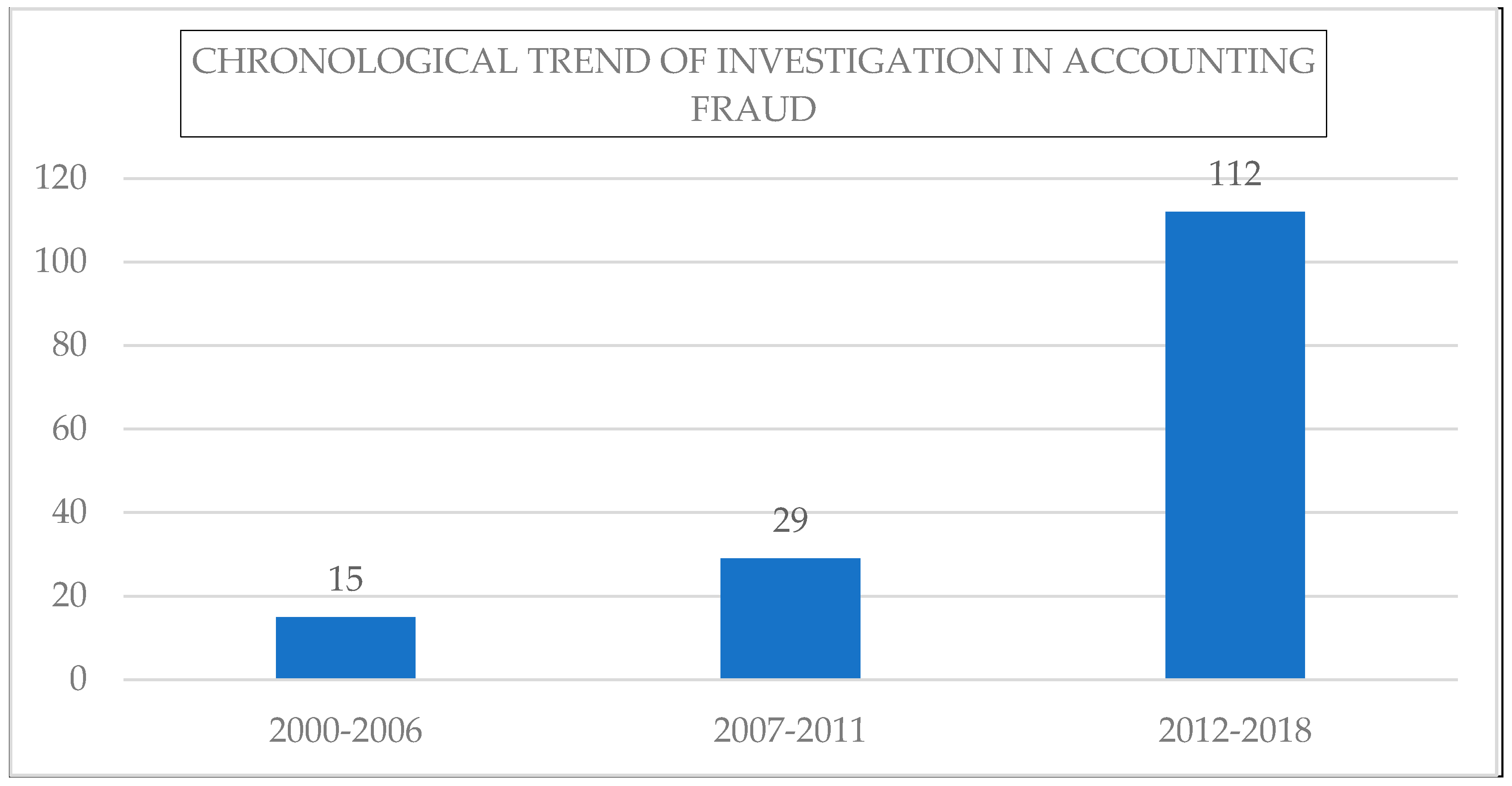

4. Analysis of Investigation in Accounting Fraud

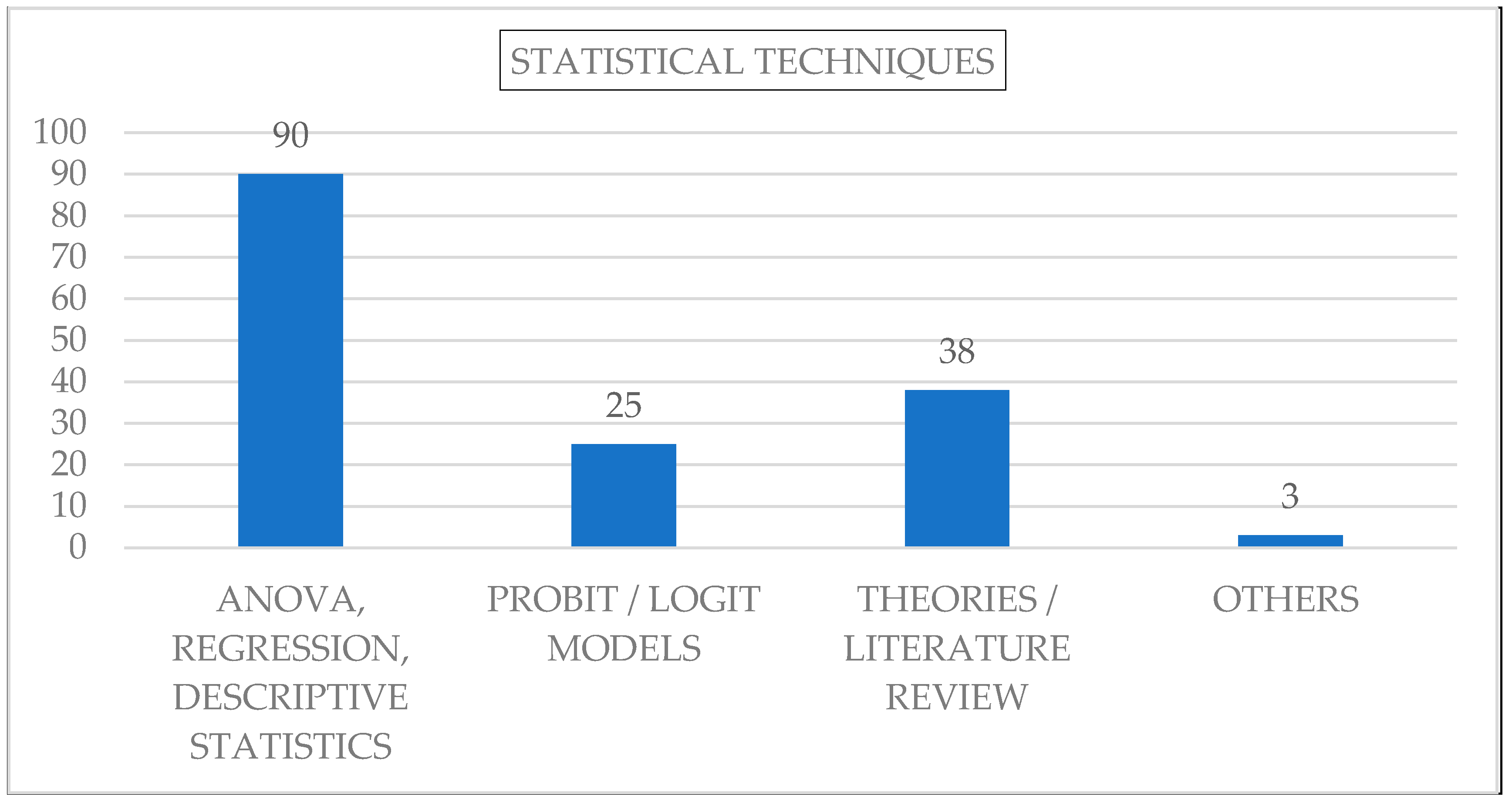

4.1. Statistical Techniques Used in the Investigation of Accounting Fraud

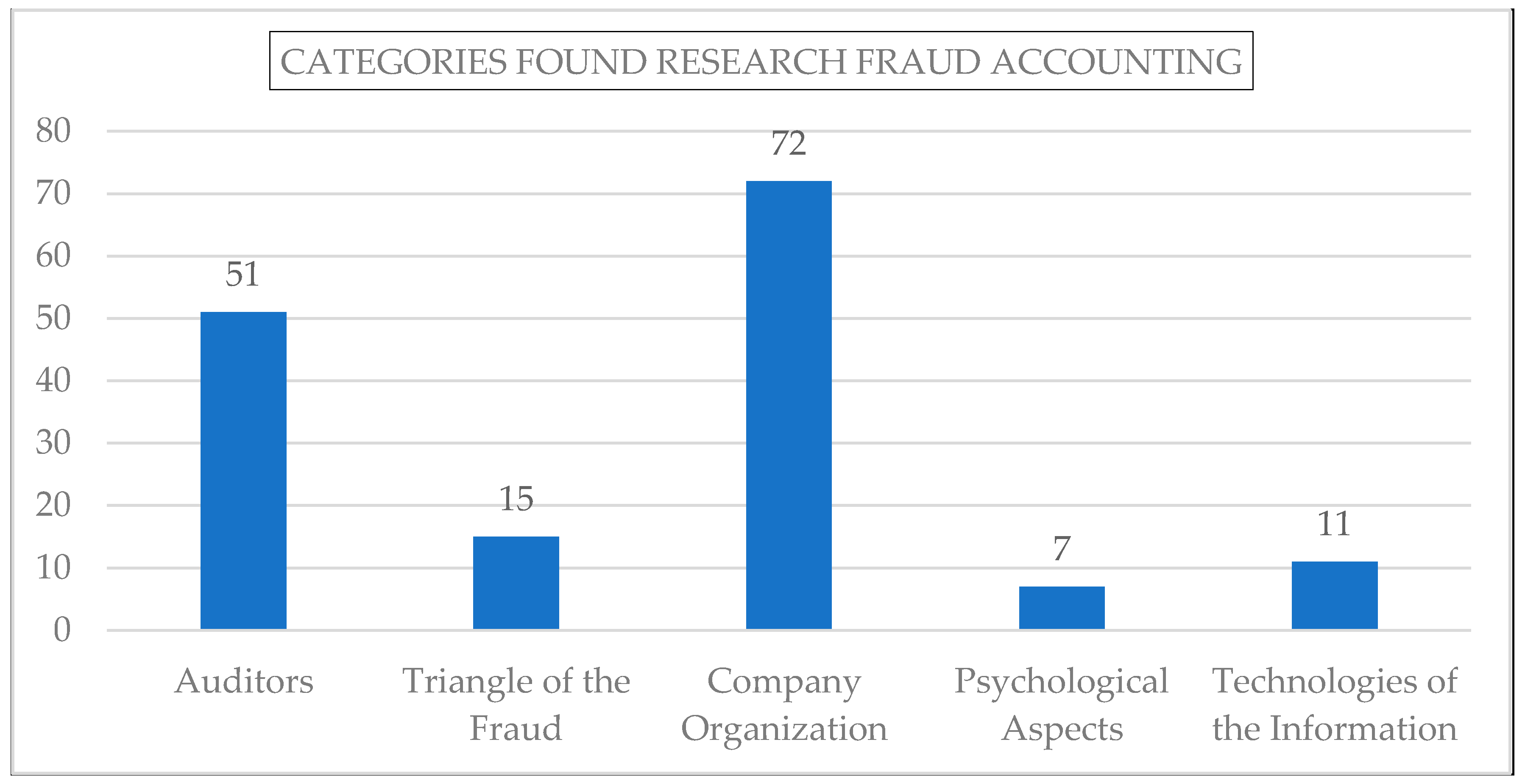

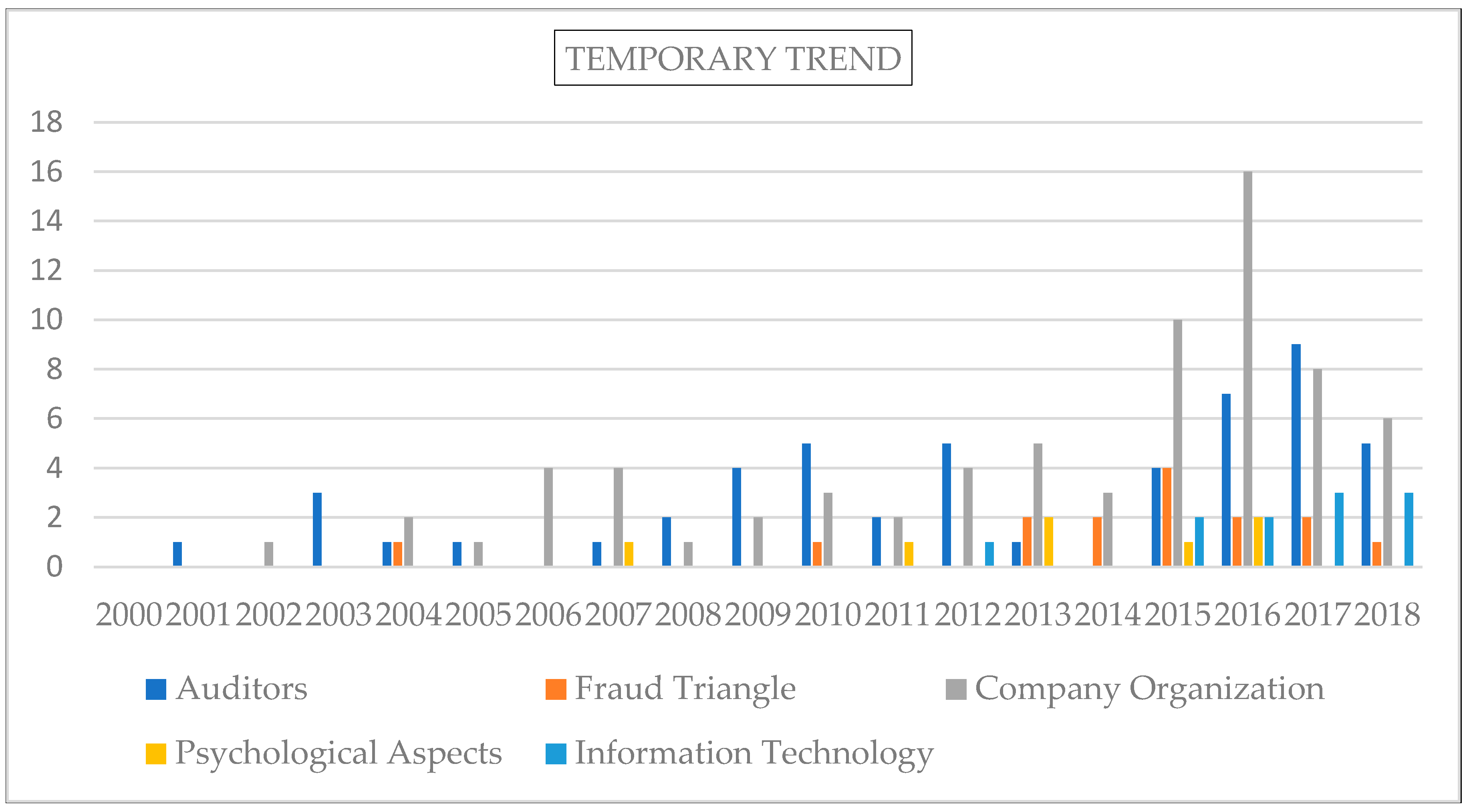

4.2. Topics, Temporary Trends and Main Findings Studied in Accounting Fraud

4.2.1. Auditors

4.2.2. The Fraud Triangle

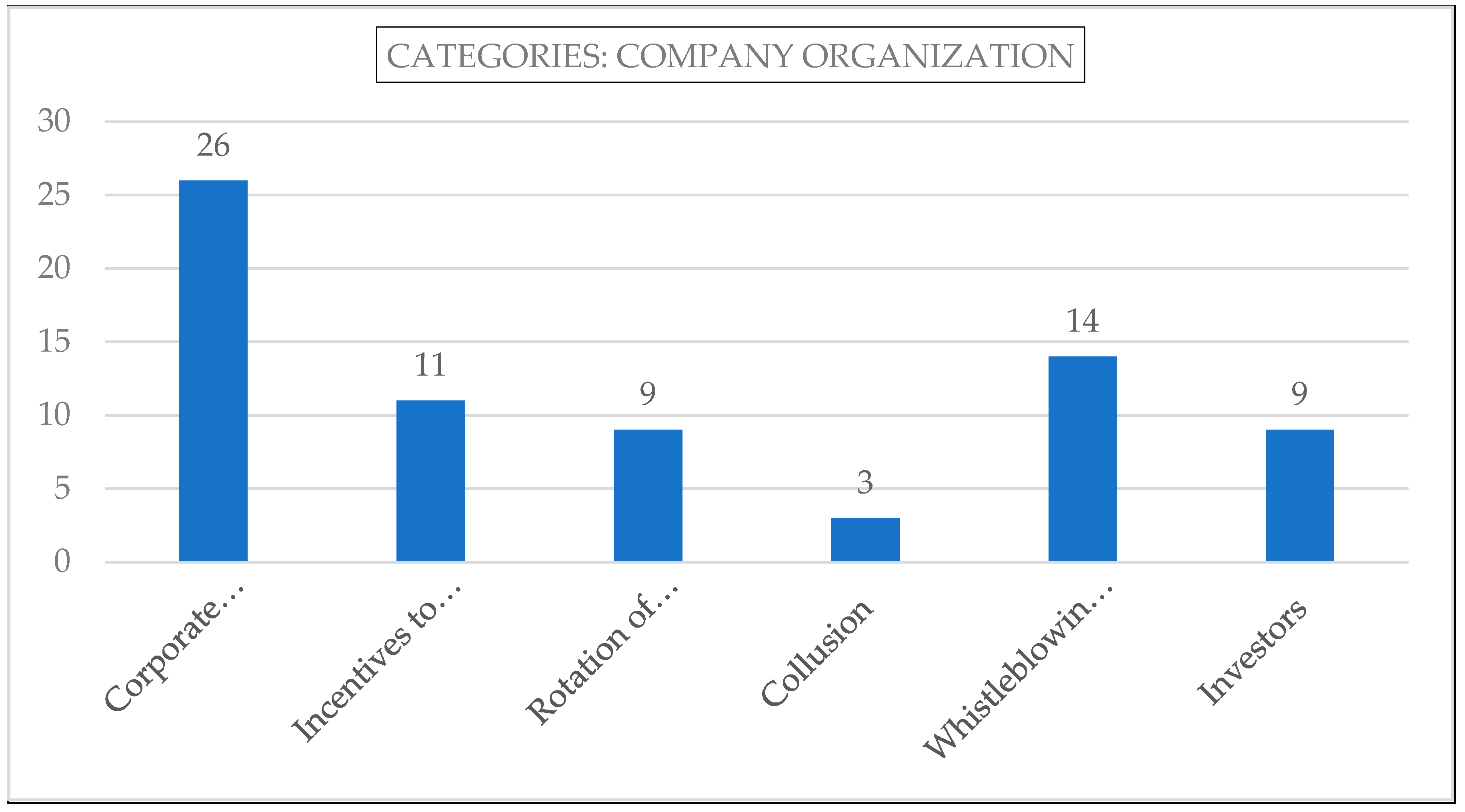

4.2.3. Company Organization

Corporate Governance/Board of Directors

Incentives to Management

Rotation of Directors/Connections of Managers

Collusion

Whistleblowing and Media

Investors

4.2.4. Psychological Aspects

4.2.5. Information Technology

5. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heal, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: An economic and financial framework. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Pract. 2005, 30, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S. Accountable governance, accountable sustainability? A case study of accountability in the governance for sustainability. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, 20, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, G.J. Business ethics and corporate governance: A global survey. Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigues Walker, A.; Trullenque, F. Responsabilidad social corporativa: ¿papel mojado o necesidad estratégica? Harv. Deusto Bus. Rev. 2008, 164, 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Park, M.S.; Wier, B. Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 761–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. Sustainability, Accountability and Corporate Governance: Exploring Multinationals’ Reporting Practices. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2008, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Barnett, M.L. Opportunity Platforms and Safety Nets: Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Risk. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2002, 105, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ferrero, J.; Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Fernandez-Fernandez, J.M. Responsabilidad social corporativa vs. responsabilidad contable. Rev. Contab. 2013, 16, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpoff, J.M.; Koester, A.; Lee, D.S.; Martin, G.S. A critical analysis of databases used in financial misconduct research. Ssrn Electron. J. 2012, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACFE. 2018 Report to the Nations; Association of Certified Fraud Examiners: Austin, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, S.M.; Othman, R. Board of Director’s Attributes as Deterrence to Corporate Fraud. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Economic Crime: A Threat to Business Globally; PwC: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- ACFE. 2014 Report To the Nations; Association of Certified Fraud Examiners: Austin, TX, USA, 2014; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Velikonja, U. the Cost of Securities Fraud. William Mary Law Rev. 2013, 54, 1887–1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaf, R.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J.; Máté, D. An investigation of the influence of theworldwide governance and competitiveness on accounting fraud cases: A cross-country perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helge, L.; Müller, M.A.; Vergauwe, S. Tournament incentives and corporate fraud. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 34, 251–267. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.M.; Peng, E.Y. An Analysis of Accounting Frauds and the Timing of Analyst Coverage Decisions and Recommendation Revisions: Evidence from the US. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2013, 40, 399–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolowy, H. Creative Accounting, Fraud and International Accounting Scandals. TAR 2012, 87, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Mcafee, R.P.; Williams, M. Fraud cycles. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. Jite 2016, 172, 544–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghghaleh, S.F.; Mohamed, Z.M.; Rahmat, M.M. Detecting Financial Statement Frauds in Malaysia: Comparing the Abilities of Beneish and Dechow Models. Asian J. Account. Gov. 2016, 7, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Akkeren, J.; Buckby, S. Perceptions on the Causes of Individual and Fraudulent Co-offending: Views of Forensic Accountants. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botes, V.; Saadeh, A. Exploring Evidence to develop a nomenclature for forensic accounting. Pac. Account. Rev. 2018, 30, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiram, D.; Bozanic, Z.; Cox, J.D.; Dupont, Q.; Karpoff, J.M.; Sloan, R.G. Financial Reporting Fraud and Other Forms of Misconduct: A Multidisciplinary Review of the Literature. Rev. Account. Stud. 2018, 23, 732–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Brink, A.G. Whistleblowing studies in accounting research: A review of experimental studies on the determinants of whistleblowing. J. Account. Lit. 2017, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.K.; Debnath, J. forensic accounting: A blend of Knowledge. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2017, 25, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, F.A.; Fadlalla, A.M. Data mining applications in accounting: A review of the literature and organizing framework. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2017, 24, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepp, A.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; O’Neill, T.J.; Smith, T. Big data techniques in auditing research and practice: Current trends and future opportunities. J. Account. Lit. 2018, 40, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Gendron, Y.; Guénin-Paracini, H. The construction of the risky individual and vigilant organization: A genealogy of the fraud triangle. Account. Organ. Soc. 2014, 39, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, G.M.; Carpenter, T.D.; Jones, K.L.; Riley, R.A. Insights for research and practice: What we learn about fraud from other disciplines. Account. Horiz. 2014, 28, 769–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, G.M.; Carpenter, T.D.; Desai, N.; Jones, K.L.; Riley, R.A. A Synthesis of Fraud-Related Research. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2013, 32, 287–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.E.; Rezaee, Z.; Riley, R.A.; Velury, U. Financial statement fraud: Insights from the academic literature. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2008, 27, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, R.G.; Melendy, S.R.; Perri, F.S. Commentary from the American accounting association’s 2011 annual meeting panel on emerging issues in fraud research. Account. Horiz. 2012, 26, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Bhattacharya, M. Intelligent financial fraud detection: A comprehensive review. Comput. Secur. 2016, 57, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Morse, A.; Zingales, L. Who blows the Whistle on Corporate Fraud? J. Financ. 2010, 65, 2213–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, E.; Peyer, U.; Stefanescu, I. Financial Misrepresentation and its impact on rivals. Financ. Manag. 2012, 41, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCAOB. AU Section 316 Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit; PCAOB: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 167–218. [Google Scholar]

- IFAC. NIA 240. Responsabilidades del auditor en la auditoría de estados financieros con respecto al fraude; IFAC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, C.; Smith, K.G.; Domino, M.A. CEO demographics and accounting fraud: Who is more likely to rationalize illegal acts? Strateg. Organ. 2011, 9, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.E.; Pope, K.R.; Samuels, J.A. An Examination of the Effect of Inquiry and Auditor Type on Reporting Intentions for Fraud. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieschwietz, R.J.; Schultz, J.J., Jr.; Zimbelman, M.F. Empirical research on external auditors’ detection of financial statement fraud. J. Account. Lit. 2000, 19, 190–246. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, C.A.; Knapp, M.C. The efects of experience and explicit fraud risk assessment in detecting fraud with analytical procedures. Account. Organ. Soc. 2001, 26, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerges, A. Auditors’ responsibility for fraud detection: New wine in old bottles? Available online: www.scribd.com/doc/63671899/Auditors-Responsibility-for-Fraud-Detection (accessed on 3 November 2012).

- Imoniana, J.O.; de Feitas, E.C.; Jacob Perera, L.C. Assessment of internal control systems to curb corporate fraud—Evidence from Brazil. Afr. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2016, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.S.; Pesch, H.L. Fraud dynamics and controls in organizations. Account. Organ. Soc. 2013, 38, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.L.; Jaffar, N.; Ab Razak, R. The Effect of Competency on Internal Auditors’ Contribution to Detect Fraud in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 29th IBIMA Conference, Vienna, Austria, 3–4 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mubako, G.; O’Donnell, E. Effect of fraud risk assessments on auditor skepticism: Unintended consequences on evidence evaluation. Int. J. Audit. 2018, 22, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.R.R.; Gartner, I.R. The Cressey hypothesis (1953) and an investigation into the occurrence of corporate fraud: An empirical analysis conducted in Brazilian banking institutions. Rev. Contab. Finanç. 2017, 29, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C.; Holland, D.; Malagueño, R.; Dolan, S.; Tzafrir, S. The Role of Power in Financial Statement Fraud Schemes. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchter, A.; Levi, M. Beyond the fraud triangle: Swiss and Austrian elite fraudsters. Account. Forum 2015, 39, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokanan, M.E. Challenges to the fraud triangle: Questions on its usefulness. Account. Forum 2015, 39, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, B. The Anatomy of Corporate Fraud: A Comparative Analysis of High Profile American and European Corporate Scandals. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbouni, S.S.; Obeid, N.; Garbou, A. Corporate governance and information technology in fraud prevention and detection: Evidence from the UAE. Manag. Audit. J. 2016, 31, 589–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Ryan, H.E.; Tian, Y.S. Managerial Incentives and Corporate Fraud: The Sources of Incentives Matter. Rev. Financ. 2009, 13, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/SustainAbility. Risk & Opportunity: Best Practice in Non-Financial Reporting; SustainAbility: London, UK, 2004; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Cooper, T. Corporate Governance Consequences of Accounting Scandals: Evidence from Top Management, CFO and Auditor Turnover. Q. J. Financ. 2017, 7, UNSP 1650014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneish, M.D.; Marshall, C.D.; Yang, J. Explaining CEO retention in misreporting firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 123, 512–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persons, O.S. The Effects of Fraud and Lawsuit Revelation on U.S. Executive Turnover and Compensation. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, V.; Kim, E.H.; Lu, Y. CEO Connectedness and Corporate Fraud. J. Financ. 2015, 70, 1203–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Securities Fraud and Corporate Finance: Recent Developments. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2013, 34, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.; Murphy, P.R. The ties that bind: The decision to co-offend in fraud. Contemp. Account. Res. 2015, 32, 18–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.H.; Jawahar, I.M.; Kisamore, J.L. Using the theory of planned behavior and cheating justifications to predict academic misconduct. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Fargher, N. Companies’ Use of Whistle-Blowing to Detect Fraud: An Examination of Corporate Whistle-Blowing Policies. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D.; Rosanas, J.M.; Fontrodona, J. Ethics in Finance and Accounting: Editorial Introduction. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Winton, A.; Yu, X. Corporate fraud and business conditions: Evidence from IPOs. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 2255–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazel, J.F.; Jones, K.L.; Thayer, J.; Warne, R.C. Understanding investor perceptions of financial statement fraud and their use of red flags: Evidence from the field. Rev. Account. Stud. 2015, 20, 1373–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorti, S.; Olsen, W.P. Fraud the Human Factor. Financ. Exec. 2007, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Doerr, B.; Chatman, J.A. “See You in Court”: How CEO narcissism increases firms’ vulnerability to lawsuits. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.N.; Kuhn, J.R.; Apostolou, B.A.; Hassell, J.M. Auditor Perceptions of Client Narcissism as a Fraud Attitude Risk Factor. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2013, 32, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijsenbilt, A.; Commandeur, H. Narcissus Enters the Courtroom: CEO Narcissism and Fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderre, D.; Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Continuous Auditing: Implications for Assurance, Monitoring, and Risk Assessment. Glob. Technol. Audit Guid. 2005, 3, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Perols, J.L.; Bowen, R.M.; Zimmermann, C.; Samba, B. Finding needles in a haystack: Using data analytics to improve fraud prediction. Account. Rev. 2017, 92, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Wirth, C. Detecting fraud in Chinese listed company balance sheets. Pac. Account. Rev. 2017, 29, 356–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kogan, A. Designing confidentiality-preserving Blockchain-based transaction processing systems. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2018, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Bhattacharya, M. An Investigation on Experimental Issues in Financial Fraud Mining. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 80, 1734–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, I.; Dutta, S.; Raahemi, B. Detecting financial restatements using data mining techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 90, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcello, J.V.; Hermanson, D.R.; Ye, Z. Corporate Governance Research in Accounting and Auditing: Insights, Practice Implications, and Future Research Directions. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Xiao, X. Whistleblowing on accounting-related misconduct: A synthesis of the literature. J. Account. Lit. 2018, 41, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnatterly, K.; Gangloff, K.A.; Tuschke, A. CEO Wrongdoing: A Review of Pressure, Opportunity, and Rationalization. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2405–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotman, K.T.; Wright, W.F. Triangulation of audit evidence in fraud risk assessments. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boritz, J.E.; Kochetova-Kozloski, N.; Robinson, L. Are fraud specialists relatively more effective than auditors at modifying audit programs in the presence of fraud risk? Account. Rev. 2015, 90, 881–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, S.K.; Wright, A.M. The Effectiveness of Alternative Risk Assessment and Program Planning Tools in a Fraud Setting. Contemp. Account. Res. 2004, 21, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coram, P.; Ferguson, C.; Moroney, R. Internal audit, alternative internal audit structures and the level of misappropriation of assets fraud. Account. Financ. 2008, 48, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, L.H.; Tarsalewska, M.; Zhan, F. Equity Incentives and Corporate Fraud in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, D.B. Restoring Trust after Fraud:Does Corporate Governance Matter? Account. Rev. 2005, 80, 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, H.; Szewczyk, S.H.; Varma, R. Board Composition and Corporate Fraud. Financ. Anal. J. 2004, 60, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eutsler, J.; Nickell, E.B.; Robb, S.W.G. Fraud risk awareness and the likelihood of audit enforcement action. Account. Horiz. 2016, 30, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, W.S.; Albrecht, C.; Albrecht, C.C. Current Trends in Fraud and its Detection. Inf. Secur. J. A Glob. Perspect. 2008, 17, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Ownership Incentives and Management Fraud. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2007, 34, 1123–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povel, P.; Singh, R.; Winton, A. Booms, Busts, and Fraud. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2007, 20, 1219–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, M.A.; Wingreen, S.C.; Blanton, J.E. Social Cognitive Theory: The Antecedents and Effects of Ethical Climate Fit on Organizational Attitudes of Corporate Accounting Professionals—A Reflection of Client Narcissism and Fraud Attitude Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.M.J.; Ahmad, A.C.; Samsudin, R.S. An Examination of Task Performance Fraud Risk Assessment on Forensic Accountant Knowledge and Mindset in Nigerian Public Sector. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffett, A.B. Can Identifying and Investigating Fraud Risks Increase Auditors’ Liability? Account. Rev. 2010, 85, 2145–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, V.B.; Zimbelman, M.F. Do Strategic Reasoning Brainstorming Help Auditors Change Their Standard Audit Procedures in Response to Fraud Risk? Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 811–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.A. Individual Auditors’ Identification of Relevant Fraud Schemes. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2012, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, T.J.; Turner, J.L. Auditor Identification of Fraud Risk Factors and their Impact on Audit Programs. Int. J. Audit. 2005, 9, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, S.W.; Ray Whittington, O.; Landsittel, D. Auditing firms’ fraud risk assessment practices. Account. Horiz. 2001, 15, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, E.E. When do auditors use specialists’ work to improve problem representations of and judgments about complex estimates? Account. Rev. 2018, 93, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, S. Exploring expectation gap among independent auditors’ points of view and university students about importance of fraud risk components. Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 9, 305–331. [Google Scholar]

- Holtfreter, K. Fraud in US organisations: An examination of control mechanisms. J. Financ. Crime 2004, 12, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T.D.; Reimers, J.L.; Fretwell, P.Z. Internal Auditors’ Fraud Judgments: The Benefits of Brainstorming in Groups. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Khalifa, A.S.; Trotman, K.T. Facilitating Brainstorming: Impact of Task Representation on Auditors’ Identification of Potential Frauds. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, T.; Lipicnik, M. Internal Audits of Frauds in Accounting Statements of a Construction Company. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 21, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, E.; Wright, D. Evidence of Fraud, Audit Risk and Audit Liability Regimes. Rev. Account. Stud. 2003, 8, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.; Noel, J. Audit Strategies and Multiple Fraud Opportunities of Misreporting and Defalcation. Contemp. Account. Res. 2003, 20, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, S.M.; Prawitt, D.F.; Schultz, J.J.; Zimbelman, M.F. A Test of Changes in Auditors’ Fraud-Related Planning Judgments since the Issuance of SAS No. 82. Audit: A J. Pract. Theory 2003, 22, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, M.; Mo, P.L.; Wong, R.M. Financial Statements Fraud and Auditor Sanctions: An Analysis of Enforcement Actions in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 62, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T.D. Audit Team Brainstorming, Fraud Risk and Fraud Risk Identification, Assessment: Of SAS No. 99 Implications. Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 1119–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerler, W.A.; Killough, L.N.; Iii, W.A.K. The Effects of Satisfaction with a Client’s Management During a Prior Audit Engagement, Trust, and Moral Reasoning on Auditors’ Perceived Risk of Management Fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 85, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazel, J.F.; Jones, K.L.; Zimbelman, M.F. Using Nonfinancial Measures to Assess Fraud Risk. J. Account. Res. 2009, 47, 1135–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotman, K.T.; Simnett, R.; Khalfia, A. Impact of the Type of Audit Team Discussions on Auditors’ Generation of Material Frauds. Contemp. Account. Res. 2009, 26, 1115–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, J.S.; Bamber, E.M.; Carpenter, T.D. The Influence of Documentation Specificity and Priming on Auditors’ Fraud Risk Assessments and Evidence Evaluation Decisions. Account. Rev. 2010, 85, 547–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunton, J.E.; Gold, A. A Field Experiment Comparing the Outcomes of Three Fraud Brainstorming Procedures: Nominal Group, Round Robin, and Open Discussion (Retracted). Account. Rev. 2010, 85, 911–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazel, J.F.; Carpenter, T.D.; Jenkins, J.G. Auditors’ Use of Brainstorming in the Consideration of Fraud: Reports from the Field. Account. Rev. 2010, 85, 1273–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.S.; Rose, A.M.; Rose, J.M. Internal Audit reporting lines, fraud risk decomposition, and assessments of fraud risk. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, J.S.; Johnstone, K.M.; Kadous, K. How Do Audit Seniors Respond to Heightened Fraud Risk? Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.; Knechel, W.R.; Wallage, P. The Effect of the Strictness of Consultation Requirements on Fraud Consultation. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 925–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L.; Murthy, U.S.; Engle, T.J. Why computer-mediated communication improves the effectiveness of fraud brainstorming. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 334–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullkvist, B.; Jokipii, A. Perceived importance of red flags across fraud types. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markelevich, A.; Rosner, R.L. Auditor Fees and Fraud Firms. Contemp. Account. Res. 2013, 30, 1590–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.M.J.; Che-Ahmad, A.B.; Samsudin, R.S. An empirical investigation of fraud risk assessment and knowledge requirement on fraud related problem representation in Nigeria. Account. Res. J. 2015, 28, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisic, L.L.; Silveri, S.D.; Song, Y.; Wang, K. Accounting fraud, auditing, and the role of government sanctions in China. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.L. Evaluating the intentionality of identified misstatements: How perspective can help auditors in distinguishing errors from fraud. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2016, 35, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zager, K.; Malis, S.S.; Novak, A. Accountants’ views regarding the effectiveness of fraud prevention controls. In Proceedings of the 5th International Scientific Symposium Economy Of Eastern Croatia - Vision And Growth Colección: Medunarodni Znanstveni Simpozij Gospodarstvo Istocne Hrvatske-Jucer Danas Sutra, Osijek, Hrvatska, 2–4 June 2016; pp. 849–857. [Google Scholar]

- Okat, D. Deterring fraud by looking away. Rand J. Econ. 2016, 47, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.D.; Youngman, J.F. New audit partner identification rules may offer opportunities and benefits. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelson, D.C.; Ege, M.S.; McInnis, J.M. Internal control weaknesses and financial reporting fraud. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2017, 36, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lail, B.; MacGregor, J.; Marcum, J.; Stuebs, M. Virtuous Professionalism in Accountants to Avoid Fraud and to Restore Financial Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atagan, G.; Kavak, A. Relationship between fraud auditing and forensic accounting. Int. J. Contemp. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 194–223. [Google Scholar]

- Juric, D.; O’Connell, B.; Rankin, M.; Birt, J. Determinants of the Severity of Legal and Employment Consequences for CPAs Named in SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.B.; McNellis, C.; Latham, C.K. Audit firm tenure, auditor familiarity, and trust: Effect on auditee whistleblowing reporting intentions. Int. J. Audit. 2018, 22, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J. Occupational Fraud and Abuse; Obsidian Publising Company: Austin, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkul, F.U.; Pamukcu, A. Emerging Fraud: Fraud Cases from Emerging Economies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haefele, M.; Stiegeler, S.K. White Collar Crime And Accounting Fraud. Interdiscip. Manag. Res. Xii Colección Interdiscip. Manag. Res. 2016, 12, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, W.S.; Hill, N.C.; Albrecht, C.C. The Ethics Development Model Applied to Declining Ethics in Accounting. Aust. Account. Rev. 2006, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, W.E. Keeping internal auditing in-house. Int. Audit. 2000, 57, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Mui, G.; Mailley, J. A tale of two triangles: Comparing the Fraud Triangle with criminology’s Crime Triangle. Account. Res. J. 2015, 28, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, T.J.; Zimbelman, M.F. Decomposition of Fraud Risk Assessments and Auditors’ Sensitivity to Fraud Cues. Contemp. Account. Res. 2004, 21, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Ding, Y.; Lesage, C.; Stolowy, H. Corporate fraud and managers’ behavior: Evidence from the press. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 271–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favere-Marchesi, M. Effects of Decomposition and Categorization on Fraud-Risk Assessments. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2013, 32, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andon, P.; Free, C.; Scard, B. Pathways to accountant fraud: Australian evidence and analysis. Account. Res. J. 2015, 28, 10–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Söderbom, A.; Guiral, A. Corporate Social Responsibility Enhanced Control Systems Reducing the Likelihood of Fraud. J. Bus. Ethics. 2015, 131, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cumming, D.; Hou, W.; Lee, E. Does the External Monitoring Effect of Financial Analysts Deter Corporate Fraud in China? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinstein, A.; Taylor, E.Z. Fences as Controls to Reduce Accountants’ Rationalization. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Priem, R.L.; Rasheed, A.A. Understanding the Causes and Effects of Top Management Fraud. Organ. Dyn. 2007, 36, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Kubick, T.R.; Masli, A. The effects of restatements for misreporting on auditor scrutiny of peer firms. Account. Horiz. 2018, 32, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.M.; Ge, W.; Larson, C.R.; Sloan, R.G. Predicting Material Accounting Misstatements. Contemp. Account. Res. 2011, 28, 17–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, J.D.; Hegde, S.; Malone, C.B. Fraud and firm performance: Keeping the good times (apparently) rolling. Manag. Financ. 2016, 42, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M. An Empirical Analysis of the Relation between the Board of Director Composition and Financial Statement Fraud. Account. Rev. 1996, 71, 443–465. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.D. Board of Director Characteristics, Institutional Ownership, and Fraud: Evidence from Australia. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2004, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Knechel, W.R.; Marisetty, V.B.; Truong, C.; Veeraraghavan, M. Board independence and internal control weakness: Evidence from SOX 404 disclosures. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2017, 36, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, I.; Fisher, J. Corporate governance and business ethics: Insights from the strategic planning experience. Corp. Gov. 2005, 13, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieliauskas, W.; Bewley, K.; Gronewold, U.; Menzefricke, U. Misleading Forecasts in Accounting Estimates: A Form of Ethical Blindness in Accounting Standards? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.T.; Chapple, L.; Walsh, K.D. Corporate fraud culture: Re-examining the corporate governance and performance relation. Account. Financ. 2017, 57, 597–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D.; Leung, T.Y.; Rui, O. Gender Diversity and Securities Fraud. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1572–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capezio, A.; Mavisakalyan, A. Women in the boardroom and fraud: Evidence from Australia. Aust. J. Manag. 2016, 41, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zona, F.; Minoja, M.; Coda, V. Antecedents of Corporate Scandals: CEOs’ Personal Traits, Stakeholders’ Cohesion, Managerial Fraud, and Imbalanced Corporate Strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.R.; Danko, D.; Kessler, L.L. Ownership Structure, Fraud, and Corporate Governance. J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2016, 27, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; (Frank) Li, Z.; Yang, C. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Invest. Anal. J. 2016, 45, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semadeni, M.; Withers, M.C.; Trevis Certo, S. The perils of endogeneity and instrumental variables in strategy research: Understanding through simulations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castro, R.; Ariño, M.A.; Canela, M.A. Does social performance really lead to financial performance? Accounting for endogeneity. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M.B.; Linck, J.S.; Netter, J.M. Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndofor, H.A.; Wesley, C.; Priem, R.L. Providing CEOs With Opportunities to Cheat: The Effects of Complexity-Based Information Asymmetries on Financial Reporting Fraud. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1774–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.; Hanlon, M.; Maydew, E.L. Is There a Link between Executive Equity Incentives and Accounting Fraud? J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, S.Y.K.; Raman, K.K.; Sun, L.; Xu, L. Insider sales and the effectiveness of clawback adoptions in mitigating fraud risk. J. Account. Public Policy 2015, 34, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fich, E.M.; Shivdasani, A. Financial fraud, director reputation, and shareholder wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 86, 306–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugrin, J.C.; Odom, M.D. Exploring Sarbanes-Oxley’s effect on attitudes, perceptions of norms, and intentions to commit financial statement fraud from a general deterrence perspective. J. Account. Public Policy 2010, 29, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnroe, J. Perceptions of the effect of Sarbanes–Oxley on earnings management practices. Res. Account. Regul. 2006, 19, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, J.J.; Cowen, A.P. Cleaning house or jumping ship? Understanding board upheaval following financial fraud. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, J.H. The deterrent effect of employee whistleblowing on firms’ financial misreporting and tax aggressiveness. Account. Rev. 2017, 92, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Carey, P. Detecting Fraud: The Role of the Anonymous Reporting Channel. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Volchkova, N.; Zingales, L.; Dyck, A.; Volchkova, N.; Zingales, L. The Corporate Governance Role of the Media: Evidence from Russia Published by: Wiley for the American Finance Association. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1093–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.S. The Press as a Watchdog for Accounting Fraud. J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 1001–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. Creative Accounting, Fraud and International Accounting Scandals; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Johan, S.A.; Rui, O.M. Institutional Investors, Political Connections, and the Incidence of Regulatory Enforcement Against Corporate Fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C. Whistle blowers: Saints of secular culture. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 39, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciukaityte, D.; Szewczyk, S.H.; Uzun, H.; Varma, R. Governance and Performance Changes after Accusations or Corporate Fraud. Financ. Anal. J. 2006, 62, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E. Director interlocks and spillover effects of reputational penalties from financial reporting fraud. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M.; Smith, K.G.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Khanin, D.M. CEOs on the edge: Earnings manipulation and stock-based incentive misalignment. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.E.; Pany, K.; Janet, A.; Samuels, J.A.; Zhang, J. An Examination of the Effects of Procedural Safeguards on Intentions to Anonymously Report Fraud. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2009, 28, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.N.; Robertson, J.C.; Curtis, M.B. The Effects of Contextual and Wrongdoing Attributes on Organizational Employees’ Whistleblowing Intentions Following Fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, P.; Petruska, K.A. Conservatism, SEC investigation, and fraud. J. Account. Public Policy 2012, 31, 399–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmock, S.G.; Gerken, W.C. Predicting fraud by investment managers. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.C.; Xie, W.; Yi, S. Corporate fraud and the value of reputations in the product market. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 25, 16–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, T.-F.; Singh, K.; Best, P. The effectiveness of fraud detection instruments in not-for-profit organizations. Manag. Audit. J. 2015, 30, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clor-Proell, S.M.; Kaplan, S.E.; Proell, C.A. The Impact of Budget Goal Difficulty and Promotion Availability on Employee Fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 131, 773–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.J.; Pope, K.R.; Samuels, J.A. An Examination of Financial Sub-certification and Timing of Fraud Discovery on Employee Whistleblowing Reporting Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.F.; Cottrell, J.H. Fraud risk management: A small business perspective. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margret, J.; Hoque, Z. Business Continuity in the Face of Fraud and Organisational Change. Aust. Account. Rev. 2016, 26, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conyon, M.J.; He, L. Executive Compensation and Corporate Fraud in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 669–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, S.; Weber, G.J. Implementing a “Real-World” Fraud Investigation Class: The Justice for Fraud Victims Project. Issues Account. Educ. 2016, 31, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andergassen, R. Managerial compensation, product market competition and fraud. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C.F.; Bohn, J.G.; Chakraborty, A. Securities fraud and corporate board turnover: New evidence from lawsuit outcomes. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2016, 48, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onza, G.; Rigolini, A. Does director capital influence board turnover after an incident of fraud? Evidence from Italian listed companies. J. Manag. Gov. 2017, 21, 993–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gong, G.; Xu, S.; Gong, X. Corporate Fraud and Corporate Bond Costs: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 54, 1011–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunghee, A.; Park, K.M. Reputation Recovering Activities After an Accounting Fraud and Market. Korean Account. J. 2018, 27, 77–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, M.B.U.; Roudaki, J. Related party transactions and finance company failure: New Zealand evidence. Pac. Account. Rev. 2018, 30, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.R.; Dacin, M.T. Psychological Pathways to Fraud: Understanding and Preventing Fraud in Organizations. J Bus Ethics 2011, 101, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.R.; Free, C. Broadening the fraud triangle: Instrumental climate and fraud. Behav. Res. Account. 2016, 28, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuempel, K.; Oldewurtel, C.; Wolz, M. Perpetrator specific red flags to detect fraud—Value for and integration into financial audits. Betr. Forsch. Und Prax. 2016, 68, 182–208. [Google Scholar]

- Dilla, W.N.; Raschke, R.L. Data visualization for fraud detection: Practice implications and a call for future research. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2015, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purda, L.; Skillicorn, D. Accounting Variables, Deception, and a Bag of Words: Assessing the Tools of Fraud Detection. Contemp. Account. Res. 2014, 32, 1193–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, B.; Zaarour, I. Towards a Machine Learning Approach for Earnings Manipulation Detection. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2017, 10, 215–251. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, E.; Glandon, T.; Petrides, Y. Framing, decision-aid systems, and culture: Exploring influences on fraud investigations. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Baik, B.; Cho, S. Detecting financial misstatements with fraud intention using multi-class cost-sensitive learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 62, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-M.; Li, H.-Y.; Chen, H.-K. Enhancement of fraud detection for narratives in annual reports. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Liao, S.; Zhang, Z. Leveraging Financial Social Media Data for Corporate Fraud Detection. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Year | Main Contribution |

|---|---|

| Knapp and Knapp, 2001 [41] | Audit managers are more effective at assessing fraud risk than senior auditors. |

| Patterson and Wright, 2003 [103] | The responsibility and capacity of the auditor to evaluate the probability of fraud and how that evaluation is used in the planning of the audit is studied. |

| Patterson et al., 2003 [104] | The auditor’s responsibility may influence the audit. |

| Glover et al., 2003 [105] | The importance of modifying audit plans in response to changes in the risk of fraud. |

| Asare and Wright, 2004 [81] | Need for a strategic reasoning approach when addressing standard fraud risk assessment tools. |

| Firth et al., 2005 [106] | Auditors are more likely to be penalized for not detecting and reporting fraud related to material errors (exaggeration of income / assets, fictitious transactions) than with the disclosure of false financial information. |

| Carpenter, 2007 [107] | The brainstorming sessions of the audit teams generate more quality ideas about fraud than individual auditors. |

| Albrecht et al., 2008 [87] | Eliminating the factors that contribute to fraud (Fraud Triangle) or helping auditors in their detection would help detect fraud more successfully. |

| Kerler and Killough, 2009 [108] | Organizations with corporate governance in their internal auditing functions are more likely to detect fraud and self-report misappropriation of assets than those that do not. |

| Hoffman and Zimbelman, 2009 [93] | Strategic reasoning and the exchange of ideas within groups of auditors lead to more effective modifications of standard auditing procedures. |

| Brazel et al., 2009 [109] | Auditors can effectively use non-financial measures to evaluate the reasonableness of financial results and detect fraud. |

| Trotman et al., 2009 [110] | The interaction of groups of auditors for brainstorming with guidelines generates a greater quantity and quality of ideas of fraud than those groups without specified guidelines. |

| Hammersley et al., 2010 [111] | The particularity of the documentation of fraud risks, discussed during the brainstorming session, influences fraud risk assessments and test evaluation decisions. |

| Hunton and Gold, 2010 [112] | The results of three types of brainstorming groups for fraud evaluation are examined: nominal, round robin and open discussion. |

| Brazel et al., 2010 [113] | Based on SAS No. 99 and previous research in psychology, the authors develop a brainstorming model auditors can use for detecting fraud. |

| Strand et al., 2010 [114] | Internal auditors perceive more personal threats when reporting to the fraud risk audit committee, than when reporting to the top levels of the company. |

| Reffett, 2010 [92] | Auditors are more likely to be held responsible for not detecting fraud, even when they have investigated it, than otherwise. |

| Carpenter et al., 2011 [100] | The homogeneous groups of internal brainstorming auditors identify fewer frauds but with higher quality (real fraud according to SEC) than a group of internal auditors who evaluate individually (nominal group). |

| Hammersley et al., 2011 [115] | When the risk of fraud is greater, the auditing programs of internal auditors are of lower quality. |

| Trotman and Wright, 2012 [79] | Auditors use information about the client’s business model to assess the risk of fraud. |

| Simon, 2012 [94] | The identification of fraud schemes for auditors is a complex task for at least three reasons. (1) The client hides it. (2) Auditors do not have extensive experience. 3) They do not know how to detect signs of fraudulent information. |

| Brody et al., 2012 [32] | Summarize the Annual Meeting of the American Accounting Association (2011) on: the common misconceptions about fraud and forensic accounting, the lack of articles related to these topics and the opportunities for future research. |

| Gold et al., 2012 [116] | The propensity of auditors to consult obligatorily with experts in fraud would be greater if there were a high risk of fraud and there were the added pressure of a deadline for the audit. |

| Smith et al., 2012 [117] | The factors that contribute to the greater effectiveness of electronic brainstorming for stopping fraud because of a more specific focus are analyzed. |

| Gullkvist an dJokipii, 2013 [118] | They examine the difference in the perception of the importance of network flags among internal auditors, external auditors and economic crime investigators. |

| Markelevich and Rosner, 2013 [119] | The relationship between the different types of auditor fees (total, audit and other services) and fraudulent financial information is considered. Companies that pay high total fees and other services to auditors are more likely to be penalized for fraudulent financial statements. |

| Popoola et al., 2015 [120] | The participation of fraud specialists in the planning of an auditing job with a risk of fraud, involves an additional effort in time and costs without there being a clear benefit commensurate with the effort. |

| Boritz et al., 2015 [80] | Examine whether large audit firms reduce the incidence of fraud in China’s financial statements. The results highlight the role of government sanctions to ensure the quality of the audit. |

| Lisic et al., 2015 [121] | Examine whether large audit firms reduce the incidence of fraud in China’s financial statements. The results highlight the role of government sanctions to ensure the quality of the audit. |

| Chen et al., 2015 [101] | “Sequential” brainstorming leads to a greater quantity and quality of the potential frauds identified by auditors, compared with the simultaneous brainstorming. |

| Bazrafshan, 2016 [98] | The views of auditors and university students on the risks of fraud and its importance are compared. The misappropriation of assets is considered the most remarkable by the auditors, whereas the students believe it to be the management characteristics and the industry conditions. |

| Eutsler et al., 2016 [86] | Theory of Counterfactual Reasoning. Auditors may be penalized for not documenting the risk of fraud if later it is discovered that the financial statements were fraudulent. |

| Hamilton, 2016 [122] | The auditor should take into account the client’s perspective when preparing the financial statements if he/she suspects that there is an intentional erroneous statement. |

| Zager et al., 2016 [123] | Internal controls have a significant impact on the prevention of fraudulent financial information. |

| Gong et al., 2016 [19] | The frequency of fraudulent crimes has a cyclical behavior. |

| Coram et al., 2008 [82] | Changing the auditing method makes it possible to prevent the audited companies from taking advantage of the weaknesses inherent in any methodology. |

| Okat, 2016 [124] | “Sequential” brainstorming leads to a greater quantity and quality of the potential frauds identified by auditors, compared with the simultaneous brainstorming. |

| Imoniana et al., 2016 [43] | An internal claim channel and internal compliance rules are better at detecting corruption and misappropriation of assets. External auditors are better at detecting fraud in financial statements. |

| Hamdan et al., 2017 [45] | They recommended having good academic qualifications and experience in issues related to fraud in order to improve the detection of fraud. |

| Reid and Youngman, 2017 [125] | A study is carried out on the importance of publicly disclosing the company responsible for conducting the audit, as well as any other company that participates in the same. |

| Donelson et al., 2017 [126] | Having the opportunity to deceive senior managers of weak internal controls is associated with an increased risk of fraud in financial reporting. |

| Tiwari and Debnath, 2017 [25] | Forensic accountants must have specific training in accounting and personal skills to perform their work properly. |

| Wei et al., 2017 [72] | The manipulation of asset accounts is more frequent than the inflation of liabilities when it comes to adulterating financial statements. |

| Lail et al., 2017 [127] | The “virtuous” professional accountant (justice, wisdom, courage, motivation) is proposed with preventing fraudulent behavior in accounting and financial systems. |

| Perols et al., 2017 [71] | Two models are proposed that improve the prediction of fraud by 10%. |

| Atagan and Kavak, 2017 [128] | Survey of public accountants in Turkey to analyze their opinions on fraud and forensic accounting in their country and in the rest of the world. |

| Van Akkeren and Buckby, 2017 [21] | A qualitative study is carried out, using the perceptions and experiences of forensic accountants, to determine the accounting fraud carried out by individuals and groups. |

| Juric et al., 2018 [129] | Young male public certified accountants have a greater predisposition to engage in fraudulent behavior and the sanctions imposed on them by the SEC are also superior. |

| Wilson, McNellis, & Latham, 2018 [130] | The mandatory non-rotation of the audit firm is proposed, since the permanence of the auditor generates trust among the employees and this encourages the reporting of irregularities. |

| Author/year | Main Contribution |

|---|---|

| Wilks and Zimbelman, 2004 [137] | Decomposition of the Fraud Triangle into its three elements to increase the sensitivity of auditors to detect fraud. |

| Cohen et al., 2010 [138] | The Fraud Triangle and the Theory of Planned Behavior are integrated in order to detect the risk of fraud. |

| Trompeter et al., 2013 [30] | The publications on accounting and related disciplines are reviewed (criminology, ethics, finances, organizational behavior, psychology, sociology). The Fraud Triangle is combined with corporate governance and internal controls in the company. |

| Favere-Marchesi, 2013 [139] | The decomposition of fraud risk assessment into its three elements is a preferable method to assess the general risks of fraud. |

| Morales et al., 2014 [28] | The Fraud Triangle is presented as a credible technology for the study of organizational fraud. The opportunity is the primordial element. |

| Trompeter et al., 2014 [29] | Review of the literature on the constructions of the Fraud Triangle both in accounting and non-accounting (neutralization and rationalization). |

| Mui and Mailley, 2015 [136] | Propose the application of the Crime Triangle Theory (which studies the environment), to fraudulent situations as a complement to the Fraud Triangle. |

| Andon et al., 2015 [140] | Establish the importance of the attitude towards the situation in regard to fraudulent behavior. |

| Lokanan, Mark E., 2015 [50] | Fraud is a multifaceted phenomenon and the Fraud Triangle should not be seen as a sufficiently reliable model for anti-fraud professionals. |

| Schuchter and Levi, 2015 [49] | Consider that opportunity is the most important condition in fraudulent acts. Financial incentives should not lead to committing accounting fraud. |

| Rodgers et al., 2015 [141] | An Ethical Thinking Process Model is used, embedded in the Fraud Triangle, in order to better understand the interconnection of ethical positions and internal control systems to handle fraudulent situations. |

| Haefele and Stiegeler, 2016 [133] | Those who commit “white collar crime” usually do so following the same pattern: motivation, opportunity and subjective justification. |

| Chen et al., 2016 [142] | Study the role of the financial analyst in corporate fraud in China within the framework of the Fraud Triangle. The financial analyst reduces the opportunity but increases the incentive to committing fraud. The influence on rationalization depends on how much the company depends on the capital market for finance. |

| Reinstein and Taylor, 2017 [143] | The influence of ethics, morals and values is studied as obstacles in the rationalization of accounting fraud. |

| Machado and Gartner, 2017 [47] | The theoretical framework of the theory of the agency, of criminology and of the economy of crime is combined with the Fraud Triangle to study the occurrence of corporate fraud in Brazilian banking institutions. |

| Author/Year | Main Contribution |

|---|---|

| Grant, 2002 [176] | Monetary incentives for reporting fraud are seen to be positive by employees. |

| Uzun et al., 2004 [87] | Characteristics of the board of directors and corporate governance correlate with the occurrence of fraud. |

| Sharma, 2004 [149] | Importance of the percentage of independent directors on the board. Increasing the percentage of institutional property in a company decreases the probability of fraud. |

| Farber, 2005 [84] | Changes in the credibility of the financial information system and the quality of corporate governance mechanisms subsequent to the detection of fraud and the economic consequences for the company of such changes. |

| Miller, 2006 [173] | Study on the role of the press as a monitor or “watchdog” of accounting fraud, analyzing and providing information to readers at a very low cost. |

| Erickson et al., 2006 [164] | There is no relationship between the capital incentives of executives and accounting fraud. |

| Persons, 2006 [57] | Analysis of the impact of the revelation of fraud/judicial actions in the executive rotation and its compensation. |

| Marciukaityte et al., 2006 [177] | The companies increased the proportion of external directors on their board after the accusation of fraud. |

| Zahra et al., 2007 [144] | Analysis of different types of fraud committed by senior management and their effects on shareholders, employees, communities, companies and society in general. Importance of ethical leadership. |

| Povel et al., 2007 [89] | Fraud is more likely to occur in good times as the costs of surveillance diminish. |

| Sen, 2007 [88] | When looking to reduce fraud the certainty of the determination and the application of the penalty are more important than the size of fraud itself. |

| Fich, 2007 [166] | External directors do not face an abnormal rotation in the board of the company sued for fraud; they do experience a significant decrease in the boards of other companies. |

| Kang, 2008 [178] | The director’s connections with other companies act as channels that affect his/her reputation post-fraud. |

| Zhang et al., 2008 [179] | The effects of stock-based incentives on CEO earnings manipulation behaviors are examined |

| Johnson et al., 2009 [53] | Corporate fraud is an undesired result and is associated with managerial incentives. |

| Kaplan et al., 2009 [180] | There is more intention to report a fraudulent act with an internally administered telephone line. |

| Ugrin and Odom, 2010 [167] | Study on how the increase in jail time for committing fraud imposed by SOX does not offer any additional deterrence beyond the possibility of going to jail than that in the pre-SOX law. |

| Wang et al., 2010 [64] | The propensity to fraud increases with the level of investor beliefs about industry prospects, but decreases when beliefs are extremely high. |

| Dyck et al., 2010 [34] | Fraud detection is not based on standard corporate governance actors (investors, SEC, auditors), but rather on employees, the media and industry regulators. |

| Troy et al., 2011 [38] | Younger CEOs, with less experience and less academic training, are more likely to commit accounting fraud. |

| Kaplan et al., 2011 [39] | Employees are often aware of fraud before other professionals (internal and external auditors) and are more willing to report fraud to an internal auditor than to an external auditor. |

| Robinson et al., 2012 [181] | Employees are less likely to report: (1) financial statement fraud than theft; (2) when the violator is aware that the potential claimant knows about the fraud; and (3) when other employees are not aware of the fraud. |

| Alam and Petruska, 2012 [182] | The relationship between accounting conservatism and the presentation of fraudulent financial information in companies is studied. |

| Dimmock and Gerken, 2012 [183] | Study on the use of mandatory information that companies provide to the SEC in order to predict fraud. |

| Young and Peng, 2013 [17] | Investors may be able to exploit information from actions taken by analysts to uncover fraud and to protect their interests. |

| Lee and Fargher, 2013 [62] | The implementation of a direct line of services in a company is positively affected by economic factors, ethical environment and legal aspects. |

| Xiaoyun, 2013 [59] | Professional connectivity decreases financial fraud, while non-professional connectivity increases it. |

| Zona et al., 2013 [156] | Jointly analyze the personality traits of the CEO (e.g., lack of moral values, narcissism), the unbalanced strategies of the company and the support of shareholders for the CEOs who adopt unbalanced strategies, to explain their fraudulent behavior. |

| Davis and Pesch, 2013 [44] | They develop a model based on agents (employees) and how they interact with each other and with organizational variables to prevent and detect fraud. |

| Soltani, 2014 [51] | There are significant similarities in the following ethical aspects between the US and Europe: the tone of the upper part of the company; economic bubble and market pressure; fraudulent financial information; accountability; control; audit and governance; the compensation of managers. |

| Johnson et al., 2014 [184] | Existence of a causal relationship between financial misconduct and the decline in the operating performance of a company that has committed fraud. Clients impose reputational sanctions through an increase in sales costs (purchase and investment). |

| Marcel and Cowen, 2014 [169] | After the detection of financial fraud, the boards of directors experience high levels of turnover among external directors. |

| Kummer et al., 2015 [185] | They indicate three very effective measures to detect fraud in non-for-profit firms: (1) fraud control policies, (2) complaint policies and 3) fraud risk registries. |

| Clinton and Murphy, 2015 [60] | Reasons why people co-commit fraud because of its social nature. |

| Khanna et al., 2015 [58] | The connections that CEOs develop with senior executives / directors through their nominations can increase the likelihood of committing fraud and decrease the likelihood of detecting it. |

| Fung et al., 2015 [165] | Study on the proposal to change executive compensation based on incentives by reintegration clauses. |

| Ndofor et al., 2015 [163] | Having the opportunity, provided by the asymmetry of information, is what the CEO´s need to present fraudulent financial information. |

| Cumming et al., 2015 [154] | (1) Gender diversity works as a moderator for the frequency of fraud. (2) The stock market’s response to fraud is much less pronounced if the board is more diverse. (3) Women are more effective, in industries dominated by men, in reducing the frequency and severity of fraud. |

| Haß et al., 2015 [16] | The results show a positive association between CEO incentives and the propensity to engage in fraudulent behavior. |

| Albrecht et al., 2015 [48] | Using the French and Raven Power Taxonomy, a model is proposed that explains how top management influences other individuals to participate in the fraud of the financial statements. |

| Clor-Proell et al., 2015 [186] | Study on employee fraud (theft or unauthorized use of company assets) and how the difficulty of organizational goals can have an impact on the ability to rationalize it. |

| Lowe et al., 2015 [187] | Members of the lower level organization are often the first people who are aware of the fraud and are in a better position to provide information. |

| Brazel et al., 2015 [65] | Investors examine the relationships between perceptions of the frequency of fraud in financial information, the use they make of it, the performance of their own fraud risk assessments and the use of red flags. |

| Hess and Cottrell, 2016 [188] | The four main sources of fraud risk in small businesses (customers, vendors, employees, Internet) are described |

| Goldberg et al., 2016 [157] | The property of the company affects fraud. If it is dispersed it favors the manipulation of profits and if it is concentrated it encourages the appropriation of profits by corporate governance. |

| Halbouni et al., 2016 [52] | The “tone at the top” is very important for improving the integrity and ethics of the company. IT must be used for fraud investigation and detection. |

| Salleh and Othman, 2016 [11] | Good corporate governance discourages fraud. The frequency of meetings is the best mechanism to reduce it. |

| Horvat and Lipicnik, 2016 [102] | Importance of the internal audit and the establishment of internal controls to avoid fraud in the financial statements. |

| Aghghaleh et al., 2016 [20]a | The skills of the financial models (Benech’s M-score and Dechow’s F-score) are investigated to detect and predict fraud in financial statements, with the latter being more effective in forecasting it. |

| Finnerty et al., 2016 [147] | Firms are more likely to engage in securities fraud (including accounting fraud) when they have experienced a sustained period of surprisingly good performance on the stock price of up to five years before the commission of fraud. |

| Margret and Hoque, 2016 [189] | It is concluded that the static vision that underlies conventional financial statements is sometimes problematic. A continuous debate about the quality of an organization’s published finances is necessary. |

| Conyon and He, 2016 [190] | There is a significantly negative correlation between CEO compensation and corporate fraud. The CEO is penalized for fraud by reducing his salary. The compensation is lower in companies that commit more severe fraud. |

| Kern and Weber, 2016 [191] | A program for the detection of fraud developed by the University of Gonzaga is developed together with the ACFE, the police, and local and federal prosecutors. |

| Wu et al., 2016 [175] | Analysis of institutional investing factors and political connections of Chinese companies, as elements that can mitigate corporate fraud risk. |

| Andergassen, 2016 [192] | A model is proposed to study the behavior of the manager and the shareholders in a situation in which the manager has private information about the profits of the company and the shareholders use share packages to align the interests of the manager with theirs. |

| Baum et al., 2016 [193] | Relationship between the results of the collective action lawsuits for securities fraud and the rotation of the members of the board of directors. This rotation is greater when there is a demand (settled) than when the demand is not brought to an end (dismissed). |

| Hass et al., 2016 [83] | They analyze the positive influence of shares as an incentive to managers in corporate fraud in Chinese companies. |

| Capezio and Mavisakalyan, 2016 [155] | Study on how the increase in the presence of women on the board of directors helps to mitigate fraud. |

| Johansson and Carey, 2016 [171] | Study on the how channels of anonymous notification are effective in detecting fraud, especially the appropriation of assets. Small businesses benefit more from this type of channel. |

| Melé et al. 2017 [63] | Ethics should be integrated into finance and accounting, since as intentional activities they can be used to do good or for selfish interests. (?) |

| Beneish et al., 2017 [56]b | The relationship between the dismissal of CEOs who have committed fraud and the management of the company is studied. The dismissal is greater when the cost of replacing the CEO is low and when they do not both benefit from the sale of shares during the period of fraud. |

| Agrawal and Cooper, 2017 [55] | The consequences of accounting fraud for top management, executive and financial directors and external auditors are examined. For the latter, the rotation is less. |

| Yang et al., 2017 [150] | The relationship between the independence of the board of directors of a company and the disclosure of internal weaknesses is examined (high accounting risk, few resources for internal control, complexity in financial reports). The relationship between both variables is negative and greater when the CEO and the chairman are the same person. |

| Tan et al., 2017 [153] | In companies with a culture of fraud, corporate governance actions can improve the welfare of shareholders. In companies that do not have a culture of fraud this is a costly effort that reduces their efficiency. |

| Gao and Brink, 2017 [24] | Review of the literature on the reporting of irregularities. |

| Wilde, 2017 [170] | After the reporting of irregularities, companies improve the preparation of financial reports and decrease their fiscal aggressiveness. |

| D’Onza and Rigolini, 2017 [194] | The rotation that occurs in non-executive directors in Italian companies after the detection of fraud is studied. There is a negative relationship between the departure of the company by the manager and his experience. |

| Zhang et al., 2018 [195] | Bonus issues by fraudulent companies have a low credit rating and fraudulent companies are more likely to commit fraud again. |

| Sunghee and K. M. Park, 2018 [196] | The increase in the number of external directors and personnel in the internal control system of the accounting department, are the activities related to recovering the company reputation that are carried out most by companies that have committed accounting fraud. |

| Bhuiyan and Roudaki, 2018 [197] | The importance of the presence of independent directors as good practice of corporate governance of the company and of the external auditors in the review of related parties transactions. |

| Lee and Xiao, 2018 [77] | Review of the concept of reporting irregularities, analyzing the characteristics of the complainant, the characteristics of the company, the type of complaints channel provided and the consequences for the company and the complainant. |

| Author/Year | Main Contribution |

|---|---|

| Ramamoorti, 2007 [66] | The psychological factors that could influence the behavior of fraud perpetrators should also be studied. |

| Dacin and Murphy, 2011 [198] | Three psychological pathways to fraud are identified: (1) lack of awareness, (2) intuition along with rationalization of fraudulent behavior, and (3) reasoning (cost/benefit analysis of committing fraud). |

| Johnson et al., 2013 [68] | Auditors are advised to study the behavior of the CEO (narcissism), since there is a positive relationship between this variable and the motivation behind fraud. |

| Rijsenbilt and Commandeur, 2013 [69] | There is a positive relationship between CEO narcissism and fraud. They propose a measure of 15 variables to study this behavior. |

| Domino et al. 2015 [90] | Based on the Cognitive Social Theory of Bandura (1986), three significant antecedents related to the adjustment of the ethical climate in the company are analyzed: levels of focus of internal control; changes of work beforehand; ethical climate. |

| Murphy and Free, 2016 [199] | Association between the instrumental organizational climate (employees make decisions for themselves or to benefit the organization, regardless of ethical concerns), Fraud Triangle and fraud in the company. Fraud has an important social dimension. |

| Kuempel et al., 2016 [200] | The psychological and sociological aspects are integrated into the tools to be used in a financial statement audit, developing specific red flags for the perpetrators. |

| Author/Year | Main Contribution |

|---|---|

| Huerta et al. 2012 [204] | There is an influence between report production (manually or automatically) by a decision-making support system (DAS) and the cultural background of the person making the decision to investigate the fraud. |

| Dilla and Raschke, 2015 [201] | A theoretical framework is developed to predict when and how researchers can use data visualization techniques to detect fraudulent transactions. |

| Purda and Skillicorn, 2015 [202] | Adding a statistical method is proposed for analyzing the language used in the discussion and analysis of annual and quarterly reports of the company to detect fraud. |

| West and Bhattacharya, 2016 [33] | An exhaustive review of the investigation of financial fraud detection is carried out using data mining methods, focusing on techniques based on computational intelligence (CI). |

| Kim et al., 2016 [205] | Multi-class study using logistic regression, support vector machines and Bayesian networks, to detect and classify erroneous financial statements with the intention of fraud. |

| Dbouk and Zaarour, 2017 [203] | The Beneish model is compared with the manual method of the auditors to detect the manipulation of earnings, applying a supervised machine learning approach. |

| Amani and Fadlalla, 2017 [26] | Review of the literature on the application of the data mining technique in accounting. Fraud detection, financial health of the company and forensic accounting are the areas that have benefited most from this technique. |

| Chen et al., 2017 [206] | An experiment is performed using natural language processing, a Queen genetic algorithm and support vector machine, to detect fraud in the company’s annual reports. |

| Dutta et al., 2018 [75] | Predictive models are proposed to detect fraudulent intentional activities as unintentional (financial reformulations), using data mining techniques. |

| Dong et al., 2018 [207] | Detection of signs of fraud through the analysis of text data from social networks of financial platforms (theory of systemic functional linguistics (SFL). |

| Gepp et al., 2018 [27] | An underutilization of Big Data techniques in auditing is detected. The combination of these with auditing techniques and expert judgments would help early detection of accounting fraud. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos Montesdeoca, M.; Sánchez Medina, A.J.; Blázquez Santana, F. Research Topics in Accounting Fraud in the 21st Century: A State of the Art. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061570

Ramos Montesdeoca M, Sánchez Medina AJ, Blázquez Santana F. Research Topics in Accounting Fraud in the 21st Century: A State of the Art. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061570

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos Montesdeoca, Monica, Agustín J. Sánchez Medina, and Felix Blázquez Santana. 2019. "Research Topics in Accounting Fraud in the 21st Century: A State of the Art" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061570

APA StyleRamos Montesdeoca, M., Sánchez Medina, A. J., & Blázquez Santana, F. (2019). Research Topics in Accounting Fraud in the 21st Century: A State of the Art. Sustainability, 11(6), 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061570