Influence and Sustainability of the Concept of Landscape Seen in Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley Restoration Projects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Discovery of the Concept of Landscape and of the Evolution of Garden and Korea’s Landscape and Gardens

2.1. Discovery of the Concept of Landscape and Evolution of Gardens and Parks

2.2. Evolution of the Concept of Landscape and Garden Culture in South Korea

3. Discourse on History and Restoration Process of Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley

3.1. Discussions on History and Restoration Process of Cheonggye Stream

3.2. Discussions on History and Restoration Process of Suseongdong Valley

- Go just a few steps into the valley (入谷不數武)

- Under the feet, the thundering sound of flowing water (吼雷殷屐下)

- Mountain fog shrouding and wetting my body in blue color (濕翠似裹身)

- Came in the daytime, but it felt like night (晝行復疑夜)

- Neat and clean moss spread out as a bed (淨苔當舖席)

- A round pine tree looking like a roof turned upside down (圓松敵覆瓦)

- The cascading water sounded like the song of a bird in the old days (簷溜昔啁啾)

- But today, it sounds like the song of my friend (如今聽大雅)

- Feel solemn naturally in front of the upright mind of the mountain (山心正肅然)

- I can’t hear the birds singing anymore (鳥雀無喧者)

- I wish I could let the world hear this sound (願將此聲歸)

- I wish it can enlighten the unscrupulous (砭彼俗而野)

- Night clouds suddenly appear in black color (夕雲忽潑墨)

- It tells me to draw a paint like writing a poem to you (敎君詩意寫)

- Sometimes flying water droplets are wetting clothes (時飛沫濺衣)

- Cold chill cuts to the bone (凉意逼骨)

- But my soul becomes refreshed and my mind becomes clear (魂淸神爽)

- The mind becomes comfortable, and the will grows within (情逸意蕩)

- I feel a vast-flowing spirit like the Creator (浩然如與造物者)

- It seems to be playing in a good place out of this world (遊於物之外也)

- Finally, drunken with alcohol, pleasure becomes greater (遂大醉樂極)

- So, I untie my hair and sing a long song (散髮長歌)

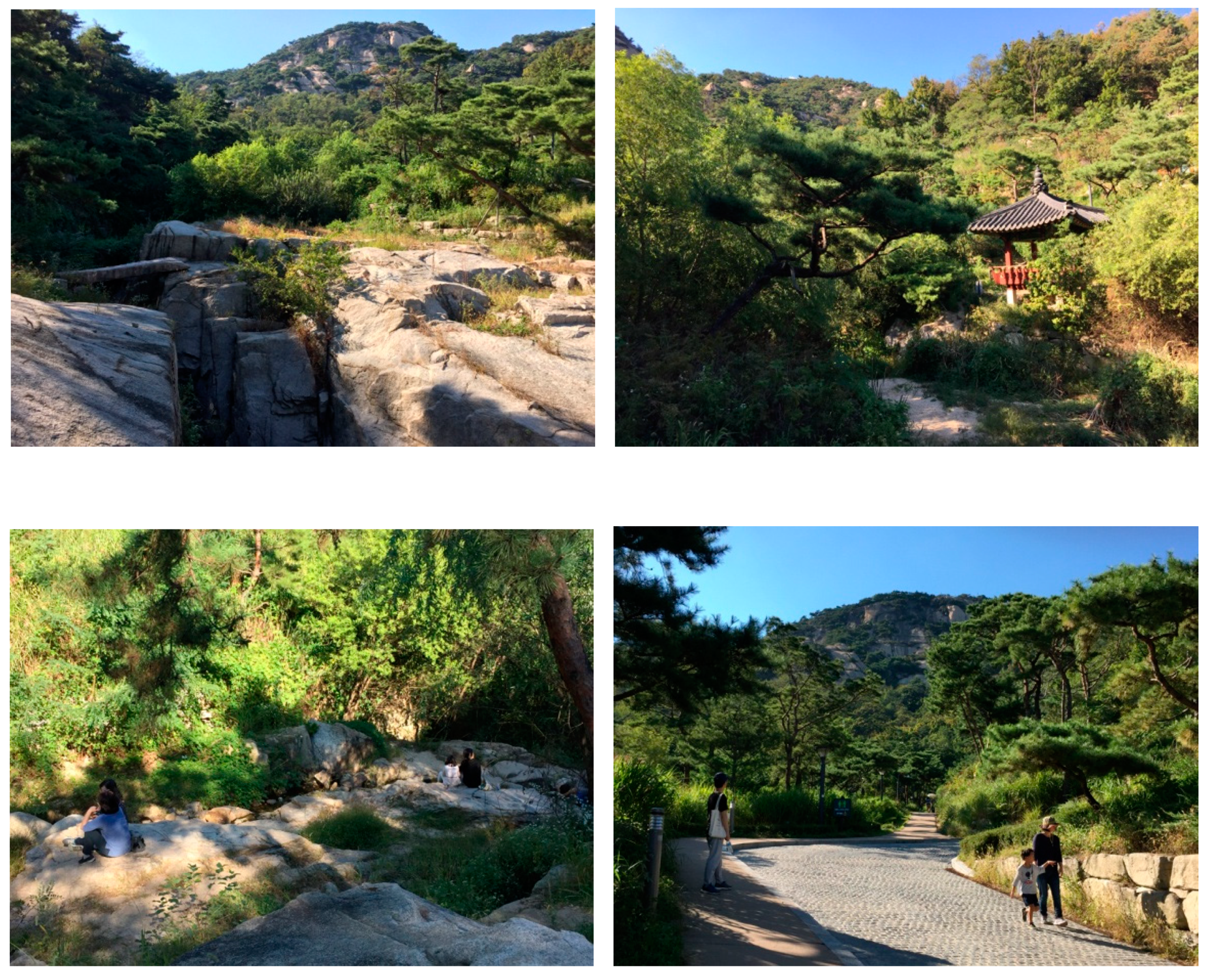

“It is worth preserving it as a ’traditional scenic spot’ because it still retains the scenery of the past. In addition, given that this area also served as the main stage for the literary activities of the middle class during the latter Joseon Dynasty, it is also meaningful from the perspective of literature history. The stone bridge hanging below the valley also appeared in the painting by Jeong Seon (with the pen name of Gyeomjae), and it is very valuable in the viewpoint of the bridge engineering history because it is the only bridge that has remained in its original location and condition within the old fortress of the capital city and also the longest bridge made of uncut stones. Therefore, it is intended to preserve the old scenery of Suseongdong by designating the entire stream and valley including a stone bridge as one of the Monuments of the Seoul Metropolitan City.”[20].

4. Influence and Sustainability of Korean concept of landscape in Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley Restoration Projects

4.1. Landscapes and Experiences in Landscape Architecture Plans of Restoration Projects

4.2. Cultural Function and Sustainability of Landscape Concept in Restoration Projects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 108–110. ISBN 9781438432762. [Google Scholar]

- Berque, A. Ecouméne: Introduction à l’étude des Milieux Humains; Editions Belin: Paris, France, 2000; ISBN 270112381X. [Google Scholar]

- The Florence Charter. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- The European Landscape Convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/about-the-convention (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Attlee, H. Italian Gardens: A Cultural History; Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7112-2647-0. [Google Scholar]

- Toriumi, M. Les Promenades de Paris de la Renaissance à l’époque Haussmannienne: Esthétique de la Nature dans l’urbanisme Parisien. Ph.D. Thesis, EHESS (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales), Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.-W. A Bowl of Scenery: Garden; Seohaemunjib: Seoul, Korea, 2001; ISBN 8974831430. [Google Scholar]

- Doosan Encyclopedia. Available online: https://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?docId=1159113&cid=40942&categoryId=32856 (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Kim, D.-H. A Study on the attitude toward nature of neo-confucianism and Toegye’s dwelling in the stream valley. Cult. Hist. Geogr. 1999, 11, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.-S.; Gin, S.-C.; Lee, S.-S. Today, Re-reading the Old Scenery; The Wisdom and Zest of the Ancestors in Traditional Landscape; Jogyeong (Landscape): Paju, Korea, 2007; pp. 8–57. ISBN 9788985507448. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.T.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.M. A semantic comparative study of formative idea and landscape elements composition of Damyang “Soswaewon(潭陽瀟灑園)” & Suzhou “Canglang Pavilion(蘇州滄浪亭)”. J. Korea Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Arch. 2017, 35, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Son, H.-W. A Study on Hidden and Exposed Characteristics of Genre Paintings of Hyewon Shin Yun-bok, Eastern Art Studies, The Korean Society of Eastern Art studies, 2018. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/search/detail/DetailView.do?p_mat_type=1a0202e37d52c72d&control_no=b7c4c950204f7eb26aae8a972f9116fb (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Seoul City Promotion Bureau. White Paper of Restoration Project of Cheonggye Stream, Seoul City; Seoul City Promotion Bureau: Seoul, Korea, 2006; pp. 58, 533–557, 639–644.

- Ryu, H.-C. Meaning formation and changes of cheong-gye-cheon as a social space. Local Hist. Cult. 2008, 11, 259–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-P. Rebirth of Cheonggyecheon, History and Environment City, Challenge of Seoul; Kimundan: Seoul, Korea, 2012; pp. 31–45. ISBN 9788962253733. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, S.J. Restoration of Cheonggye Stream for Quality of Life. Available online: https://news.v.daum.net/v/20030523073100446?f=o (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Toji Cultural Foundation. The Third Symposium on Rebirth of Cheonggye Stream; Culture and Restoration of the Stream in City; Toji Cultural Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2002; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, M.-J. Value conflict on sustainability and consensus building: The case of Cheonggyecheon restoration project. Seoul Stud. 2005, 6, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Song, I.-H. Baekundongcheon Stream a Stream Turning at Every Corner and into the Clouds; Cheonggye Stream Museum: Seoul, Korea, 2007; pp. 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage Administration, Explanation of Suseongdong Valley as Registered Heritage. Available online: http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do?pageNo=5_2_1_0&ccbaCpno=2331100310000 (accessed on 19 February 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, D.W.; Lee, J.-Y. Influence and Sustainability of the Concept of Landscape Seen in Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley Restoration Projects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041126

An DW, Lee J-Y. Influence and Sustainability of the Concept of Landscape Seen in Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley Restoration Projects. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041126

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Dai Whan, and Jae-Young Lee. 2019. "Influence and Sustainability of the Concept of Landscape Seen in Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley Restoration Projects" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041126

APA StyleAn, D. W., & Lee, J.-Y. (2019). Influence and Sustainability of the Concept of Landscape Seen in Cheonggye Stream and Suseongdong Valley Restoration Projects. Sustainability, 11(4), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041126