Winner-Takes-All or Co-Evolution among Platform Ecosystems: A Look at the Competitive and Symbiotic Actions of Complementors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Platform ecosystems

1.2. Winner-Takes-All Competitive Mindset

1.3. Focus and Purpose of Study

Are complementors’ symbiotic actions as frequent as their winner-takes-all actions, and what factors influence their competitive and symbiotic activities?

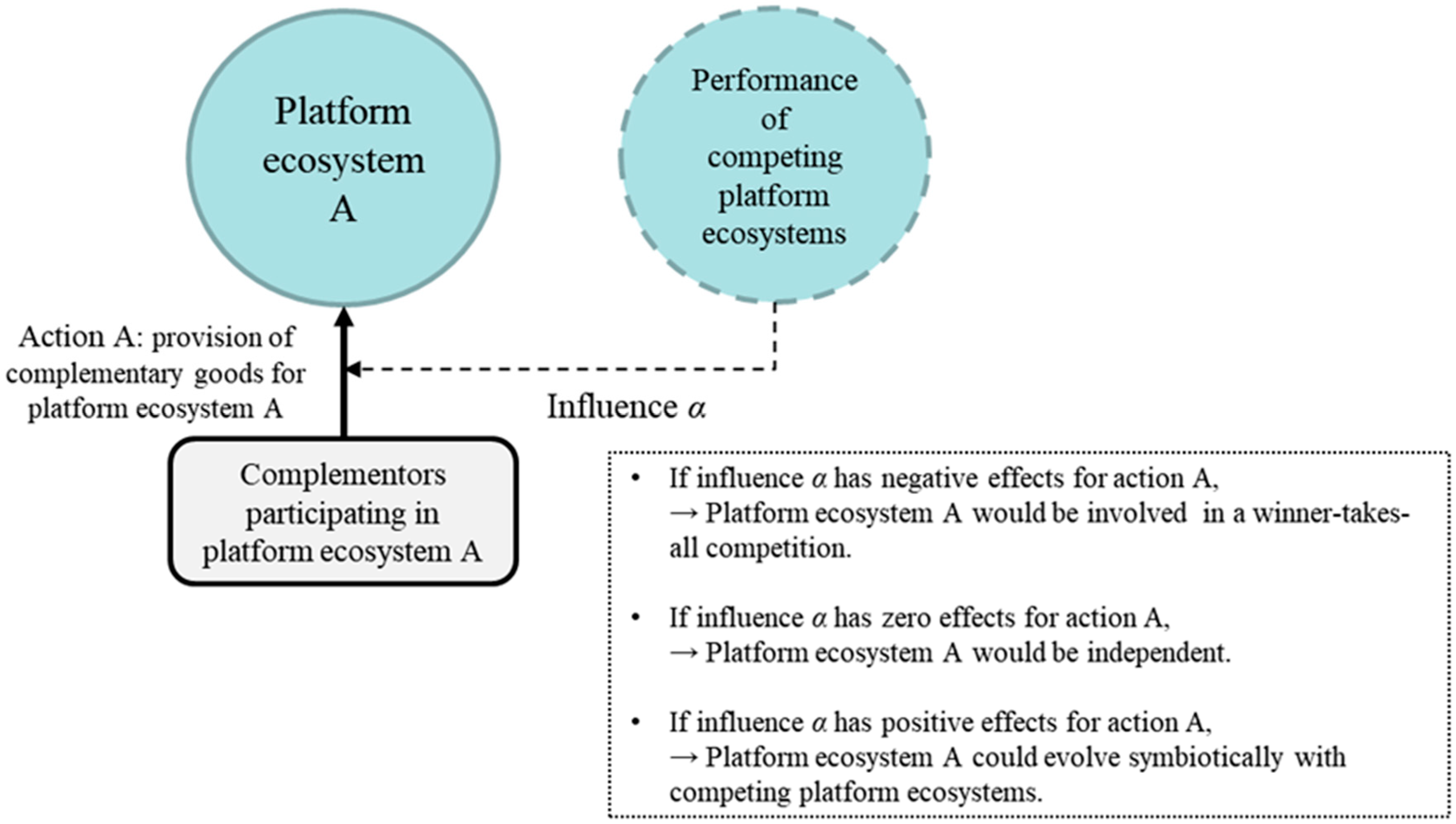

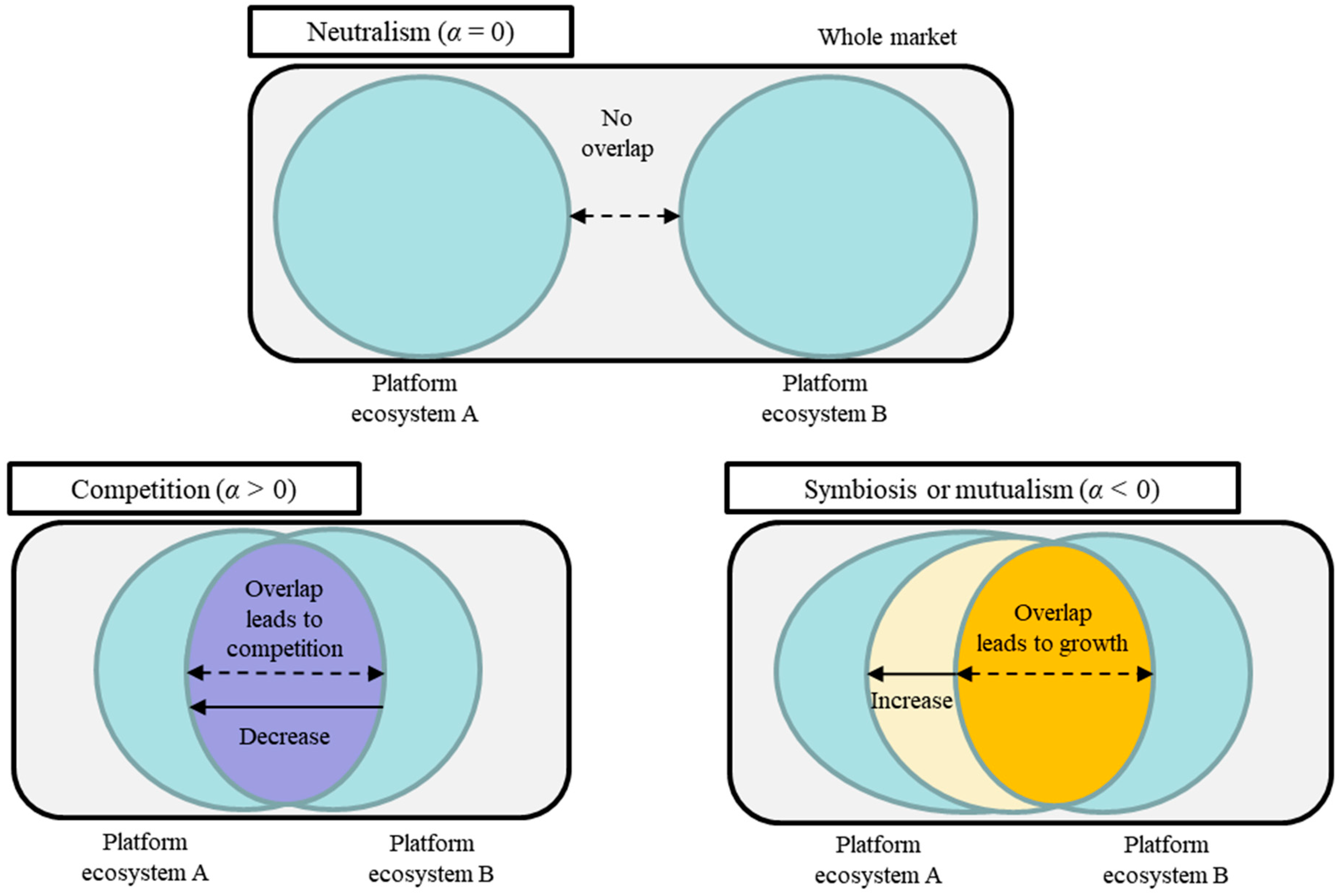

1.4. Definition of Influence α Related to Winner-Takes-All Situations for Complementors

1.5. Possible Influencial Factors on Complementors’ Competitive or Symbiotic Action

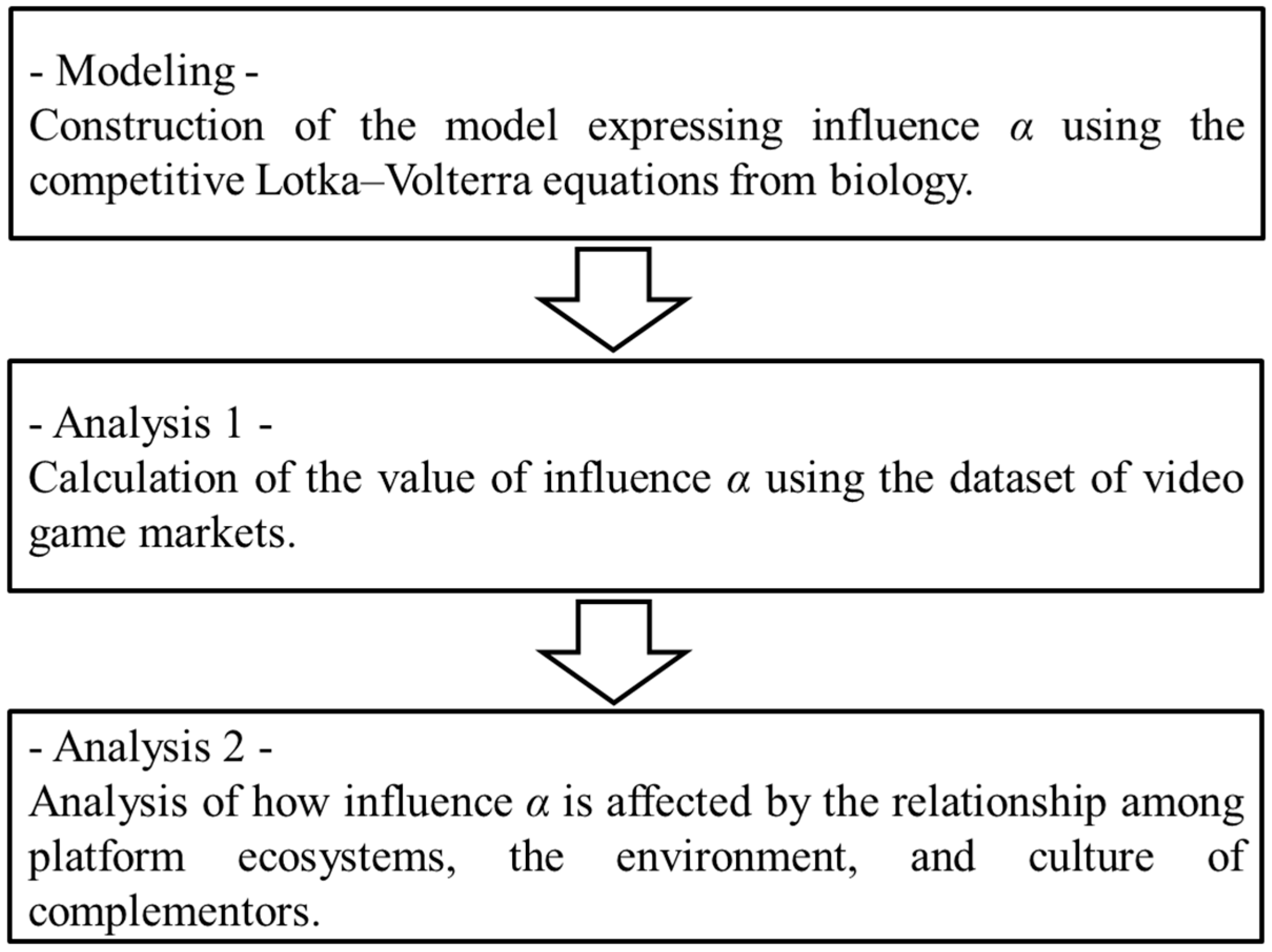

1.6. Framework of Analysis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modelling

2.1.1. Competitive Lotka–Volterra Equations

2.1.2. Differences between Competition among Species and among Platform Ecosystems

2.2. Empirical Analysis

2.2.1. Dataset

2.2.2. Analysis 1: Estimating the Value of Influence α

2.2.2.1. Modification of Competitive Lotka–Volterra Equations

2.2.2.2. Application of Dataset

- [a]

- We assumed a possible range of influence from −1.5 to 1.5 in units of 0.1. For each time period , we plugged each value of influence (−1.5~1.5) into Equation (4) and calculated the OLS regression. Here, is given as the regression coefficients.

- [b]

- In each platform and time period , we selected whose value of adjusted is at its maximum when the value of is positive.

- [c]

- To ensure the validity of the estimation of , if the significance of the estimated model on platform in time period did not satisfy the condition p < 0.01, was set as the missing value.

- [d]

- We assumed that decision making for software provision on platform is more affected by the conditions of platform than by those of other platforms. Next, when the condition was satisfied, was set as the missing value.

- [a]

- In units of 0.1 of the share of the game software provided (), we calculated the standard deviation of influence as .

- [b]

- We modeled for the estimation of depending on as . Then, we estimated and using an OLS regression.

- [c]

- Since the value of ranged from 0 to 1, we set as the standard. Then, we modified as .

2.2.3. Analysis 2: Mechanisms for Change in Influence α

2.2.3.1. Variables: Relationship among Platform Ecosystems

2.2.3.2. Variables: Environment of Platform Ecosystem

2.2.3.3. Variables: Culture of Complementors in Platform Ecosystem

2.2.3.4. Summary of Variables

2.2.3.5. Statistical Method

3. Results

3.1. Results of Analysis 1

3.2. Results of Analysis 2

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Managerial Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gawer, A. Bridging differing perspectives on technological platforms: Toward an integrative framework. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.D.W.; Autio, E.; Gann, D.M. Architectural leverage: Putting platforms in context. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Tsujimoto, M. New market development of platform ecosystems: A case study of the Nintendo Wii. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 16, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.F. The Death of Competition: Leadership & Strategy in the Age of Business Ecosystems; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. Platform Leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco Drive Industry Innovation; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, K.J.; Jeppesen, L.B. Unpaid crowd complementors: The platform network effect mirage. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccagnoli, M.; Forman, C.; Huang, P.; Wu, D.J. Cocreation of value in a platform ecosystem: The case of enterprise software. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Cenamor, J.; Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.W. Unraveling platform strategies: A review from an organizational ambidexterity perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.T.; Ohashi, H. Indirect network effects and the product cycle: Video games in the U.S., 1994–2002. J. Ind. Econ. 2005, 53, 515–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Iansiti, M. Entry into platform-based markets. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Usero, B.; Fernandez, Z. The role of complementary products on platform adoption: Evidence from the video console market. Technovation 2013, 33, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C.; Santalo, J. Platform competition: Strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1331–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, H.; Chintagunta, P.; Dube, J.P. Empirical analysis of indirect network effects in the market for personal digital assistants. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2004, 2, 22–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, H.; Lee, C.H. Within-industry diversification and firm performance in the presence of network externalities: Evidence from the software industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, K.J. Let a thousand flowers bloom? An early look at large numbers of software app developers and patterns of innovation. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, A. Evolutionary competition in platform ecosystems. Inf. Syst. Res. 2015, 26, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizingh, E.K.R.E. Open innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Technovation 2011, 31, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Why companies should have open business models. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Park, K. Dynamics from open innovation to evolutionary change. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2016, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.S. Some empirical aspects of multi–sided platform industries. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2003, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Platform competition in two-sided markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2003, 1, 990–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Two-sided markets: A progress report. Rand J. Econ. 2006, 37, 645–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiu, A.; Wright, J. Multi-Sided Platforms; Working paper no. 12-024; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiu, A.; Wright, J. Multi-sided platforms. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2015, 43, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.H.; Cook, P.J. The Winner-takes-all Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, T.R.; Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.W. Strategies for two sided markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, T.R. Winner-takes-all in networked markets. Harv. Bus. School Backgr. Note 2007, 806-131, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.; Lee, J. Reconsideration of the winner-takes-all hypothesis: Complex networks and local bias. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1838–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Downing, S. Keystone effect on entry into two-sided markets: An analysis of the market entry of WiMAX. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 94, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binken, J.L.G.; Stremersch, S. The effect of superstar software on hardware sales in system markets. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, T.R.; Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.W. Platform envelopment. Strat. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A.; Venkatraman, N. Indirect network effects and platform dominance in the video game industry: A network perspective. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2010, 57, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, E.T.; Purcarea, A.A.; Negoita, O.D. Modelling perceived risks associated to the entry of complementors’ in platform enterprises: A case study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.A. Technology success and failure in winner-takes-all markets: The impact of learning orientation, timing, and network externalities. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, L. Big losses in ecosystem niches: How core firm decisions drive complementary product shakeouts. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, P.; Järvi, K.; Kortelainen, S.; Huhtamäki, J. Winner does not take all: Selective attention and local bias in platform-based markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corts, K.; Lederman, M. Software exclusivity and the scope of indirect network effects in the U.S. home video game market. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2009, 27, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruutu, S.; Casey, T.; Kotovirta, V. Development and competition of digital service platforms: A system dynamics approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 117, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R. The technological roadmap of Cisco’s business ecosystem. Technovation 2009, 29, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkokari, K. Business, innovation, and knowledge ecosystems: How they differ and how to survive and thrive within them. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2015, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.; Gandal, N. Network effects, software provision, and standardization. J. Ind. Econ. 1992, 40, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Competition in two-sided markets. Rand J. Econ. 2006, 37, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Tsujimoto, M. Genres of complementary products in platform-based markets: Changes in evolutionary mechanisms by platform diffusion strategies. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 22, 1850004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. What is strategy? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, M.B.; Asaba, S. Why do firms imitate each other? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, P.S.; Zucker, L.G. Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations: The diffusion of civil service reform, 1880–1935. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, E. Managerial fads and fashions: The diffusion and rejection of innovations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 586–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, E.; Rosenkopf, L. Institutional and competitive bandwagons: Using mathematical modeling as a tool to explore innovation diffusion. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 487–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Prince, J.; Qiu, C. Indirect network effects and the quality dimension: A look at the gaming industry. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2014, 37, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Bayus, B.L. Network effects and competition: An empirical analysis of the home video game industry. Strat. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcraft, G.B.; Wolf, G. Dollars, sense, and sunk costs: A life cycle model of resource allocation decisions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcafee, R.P.; Mialon, H.M.; Mialon, S.H. Do sunk costs matter? Econ. Inq. 2010, 48, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.A.; Pratt, D. Analysis of the Lotka–Volterra competition equations as a technological substitution model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2003, 70, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, C.; Kondo, R.; Nagamatsu, A. Policy options for the diffusion orbit of competitive innovations—An application of Lotka–Volterra equations to Japan’s transition from analog to digital TV broadcasting. Technovation 2003, 23, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, J.I.; Arroyo-Barrigüete, J.L.; Ribeiro, D. Development of a technological competition model in the presence of network effects from the modified law of Metcalfe. Serv. Bus. 2008, 2, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalakelis, C.; Christodoulos, C.; Varoutas, D.; Sphicopoulos, T. Dynamic estimation of markets exhibiting a prey–predator behavior. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 7690–7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, F.M.; Liu, Y.L.; Wu, H.H. Market penetration among competitive innovation products: The case of the smartphone operating system. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 32, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobeck, C. N species competition. Ecology 1973, 54, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Mutualism or cooperation among competitors promotes coexistence and competitive ability. Ecol. Model. 2003, 164, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Hennig-Thurau, T. Value creation in the video game industry: Industry economics, consumer benefits, and research opportunities. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, J. Video games production networks, value capture, power relations and embeddedness. J. Econ. Geogr. 2006, 6, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Lee, C.H. Preferential linkage and network evolution: A conceptual model and empirical test in the U.S. video game sector. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 876–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polli, R.; Cook, V. Validity of the product life cycle. J. Bus. 1969, 42, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iansiti, M.; Levien, R. The Keystone Advantage: What the new Dynamics of Business Ecosystems Mean for Strategy, Innovation, and Sustainability; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, S. Nintendo Wii’s Growing Market of “Nonconsumers”. Harv. Bus. Rev. (blog). 2008. Available online: https://hbr.org/2008/04/nintendo-wiis-growing-market-o/ (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Almirall, E.; Casadesus-Masanell, R. Open versus closed innovation: A model of discovery and divergence. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.M.; Chai, K.H.; Mu, S. Capability reconfiguration of incumbent firms: Nintendo in the video game industry. Technovation 2011, 31, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D.P.; Srinivasan, A. Networks, platforms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps. Strat. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemons, E.K.; Hann, I.H.; Hitt, L.M. Price dispersion and differentiation in online travel: An empirical investigation. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yue, X.; Hua, Z. Service supply chain coordination with platform effort-induced demand. Ann. Oper. Res. 2015, 235, 785–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, F.; Yang, H.; Gao, H.O. Pricing strategies for a taxi-hailing platform. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 93, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.C.; Zhong, G.Y. The optimal pricing strategy for two-sided platform delivery in the sharing economy. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 101, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: The moderating role of product and consumer characteristics. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generation | Platform Name |

|---|---|

| 1st (standard for following generations) | Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega Master System. |

| 2nd | PC Engine, MEGA DRIVE, Super Nintendo Entertainment System, NEOGEO. |

| 3rd | NEOGEO CD, SEGA SATURN, PlayStation, PC-FX, VIRTUAL BOY, 3DO, NINTENDO64. |

| 4th | Dreamcast, PlayStation 2, NINTENDO GAMECUBE, Xbox. |

| 5th | Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, Wii. |

| 6th | Wii U, PlayStation 4, Xbox One. |

| Platform Name | Preceding Platform | Succeeding Platform | Provider | Type | Release Date in Japan | Gene-Ration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEGA SATURN | MEGA DRIVE | Dreamcast | SEGA | Stationary | Nov. 1994 | 3 |

| PlayStation | - | PlayStation 2 | Sony Computer Entertainment | Stationary | Dec. 1994 | 3 |

| PC-FX | PC Engine | - | NEC | Stationary | Dec. 1994 | 3 |

| NINTENDO 64 | Super Nintendo Entertainment System | NINTENDO GAMECUBE | Nintendo | Stationary | Jun. 1996 | 3 |

| Dreamcast | SEGA SATURN | - | SEGA | Stationary | Nov. 1998 | 4 |

| PlayStation 2 | PlayStation | PlayStation 3 | Sony Computer Entertainment | Stationary | Mar. 2000 | 4 |

| NINTENDO GAMECUBE | NINTENDO 64 | Wii | Nintendo | Stationary | Sep. 2001 | 4 |

| Xbox | - | Xbox 360 | Microsoft | Stationary | Feb. 2002 | 4 |

| Nintendo DS | GAMEBOY ADVANCE | Nintendo 3DS | Nintendo | Portable | Dec. 2004 | 5 |

| PlayStation Portable | - | PlayStation Vita | Sony Computer Entertainment | Portable | Dec. 2004 | 5 |

| Xbox 360 | Xbox | Xbox One | Microsoft | Stationary | Dec. 2005 | 5 |

| PlayStation 3 | PlayStation 2 | PlayStation 4 | Sony Computer Entertainment | Stationary | Nov. 2006 | 5 |

| Wii | NINTENDO GAMECUBE | Wii U | Nintendo | Stationary | Dec. 2006 | 5 |

| Nintendo 3DS | Nintendo DS | - | Nintendo | Portable | Feb. 2011 | 6 |

| PlayStation Vita | PlayStation Portable | - | Sony Computer Entertainment | Portable | Dec. 2011 | 6 |

| Class | Variable | Expression |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship among platform ecosystems | Degree of monopolization of platforms in the market | |

| 1. Relationship among platform ecosystems | Similarity of product category of complementary goods | |

| 1. Relationship among platform ecosystems | Embeddedness of complementors in the platforms | |

| 1. Relationship among platform ecosystems | Influence from related platforms: preceding one and succeeding one | , |

| 2. Environment of the platform ecosystem | Bias of sales volume of complementors | |

| 2. Environment of the platform ecosystem | Bias of scale of product category of complementary goods | |

| 2. Environment of the platform ecosystem | Growth and decline of the platform ecosystem: lifecycle stage 1 (introduction), stage 2 (growth), stage 3a (sustained maturity), stage 3b (maturity), stage 3c (declining maturity), and stage 4 (decline) | , , , , , |

| 3. Culture of complementors in the platform ecosystem | Degree of experience in the market | |

| 3. Culture of complementors in the platform ecosystem | Degree of new participation in the platform: rate of movers from other platforms, and rate of entrants in the market | , |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2-a | Model 2-b | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monopolization of the market | 0.06 | ** | 0.01 | 0.05 | ** | 0.00 | ||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |||||

| Similarity of product category | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.01) | |||||

| Embeddedness of complementors | −0.08 | ** | −0.06 | ** | −0.13 | ** | −0.07 | ** |

| (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.02) | |||||

| Influence of preceding platform | −0.03 | ** | −0.02 | ** | −0.03 | ** | −0.02 | ** |

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |||||

| Influence of succeeding platform | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |||||

| Bias of sales volume | 0.05 | ** | 0.04 | * | ||||

| (0.01) | (0.02) | |||||||

| Bias of product category | −0.02 | −0.03 | * | |||||

| (0.02) | (0.01) | |||||||

| Lifecycle stage: growth | −0.11 | * | −0.11 | ** | ||||

| (0.05) | (0.03) | |||||||

| Lifecycle stage: sustained maturity | −0.05 | −0.05 | ||||||

| (0.04) | (0.03) | |||||||

| Lifecycle stage: declining maturity | 0.03 | * | 0.01 | |||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |||||||

| Lifecycle stage: decline | 0.10 | ** | 0.09 | ** | ||||

| (0.03) | (0.03) | |||||||

| Experience in the market | −0.03 | * | −0.03 | * | ||||

| (0.02) | (0.01) | |||||||

| Rate of movers from other platforms | −0.06 | ** | −0.03 | ** | ||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |||||||

| Rate of entrants to the market | 0.00 | 0.03 | ** | |||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |||||||

| Intercept | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |||||

| Adjusted | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.64 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inoue, Y. Winner-Takes-All or Co-Evolution among Platform Ecosystems: A Look at the Competitive and Symbiotic Actions of Complementors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030726

Inoue Y. Winner-Takes-All or Co-Evolution among Platform Ecosystems: A Look at the Competitive and Symbiotic Actions of Complementors. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030726

Chicago/Turabian StyleInoue, Yuki. 2019. "Winner-Takes-All or Co-Evolution among Platform Ecosystems: A Look at the Competitive and Symbiotic Actions of Complementors" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030726

APA StyleInoue, Y. (2019). Winner-Takes-All or Co-Evolution among Platform Ecosystems: A Look at the Competitive and Symbiotic Actions of Complementors. Sustainability, 11(3), 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030726