Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

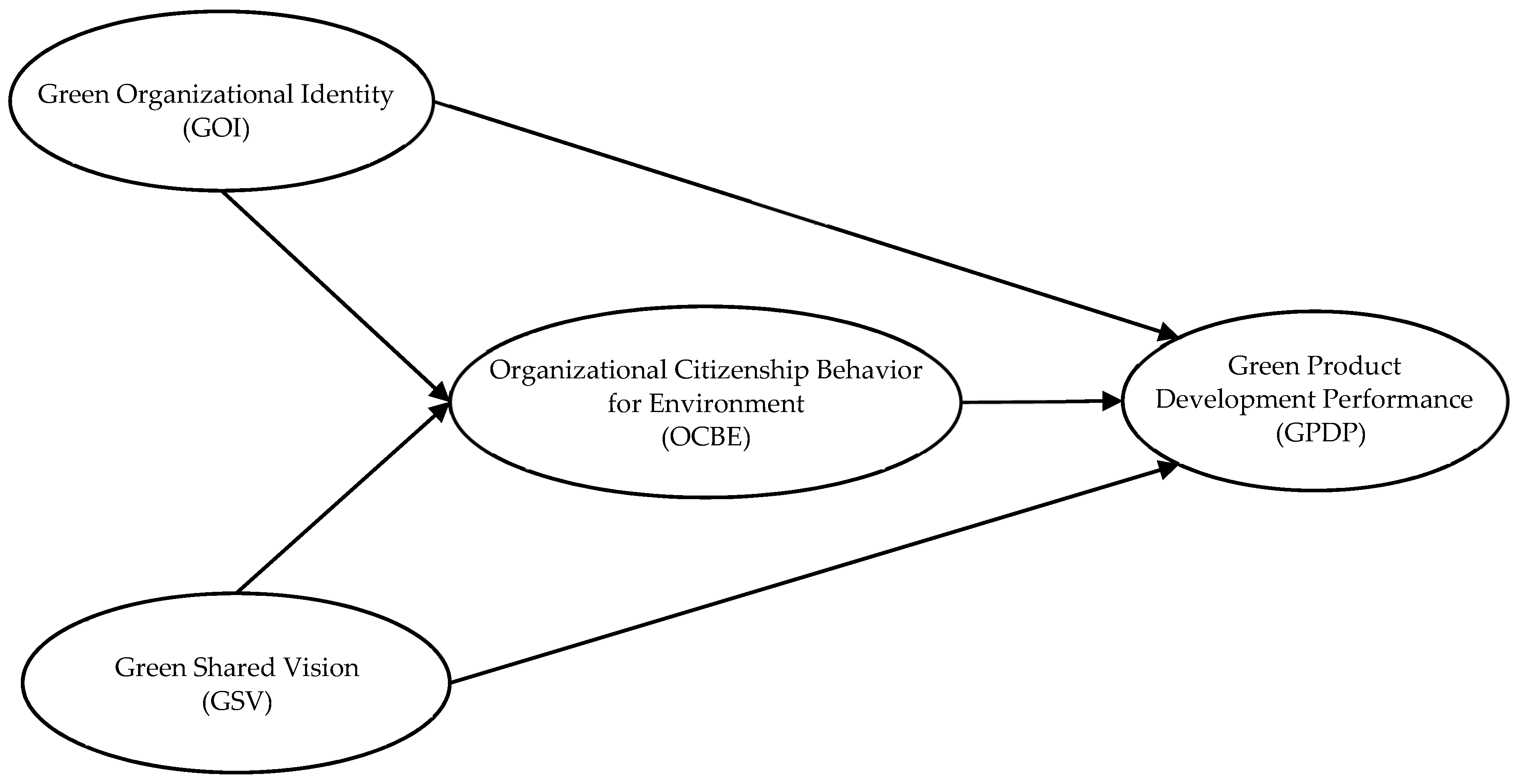

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Positive Effect of GOI on OCBE

2.2. Positive Effect of GOI on GPDP

2.3. Positive Effect of GSV on OCBE

2.4. Positive Effect of GSV on GPDP

2.5. Positive Effect of OCBE on GPDP

3. Methodology and Measurement

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Definitions and Measurements of Constructs

3.2.1. Green Organizational Identity (GOI)

3.2.2. Green Shared Vision (GSV)

3.2.3. Organizational Citizenship Behavior for Environment (OCBE)

3.2.4. Green Product Development Performance (GPDP)

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

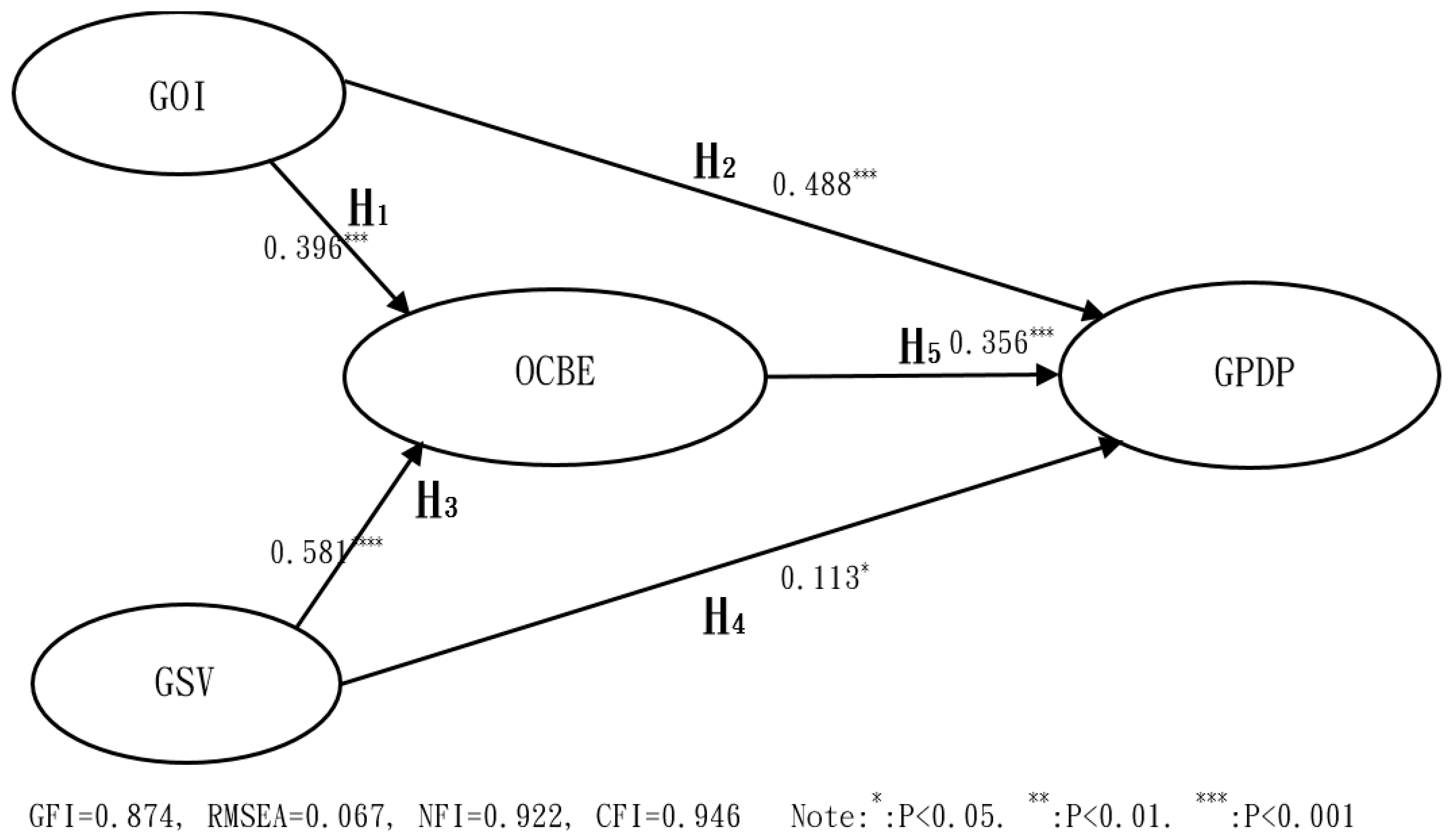

4.2. Structural Model Results

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The Determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.P.; Huang, S.J. The effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on environmental performance and business competitiveness: The mediation of green information technology capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Environmental technologies and competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate. J. Bus. Adm. Policy Anal. 1999, 73, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S. The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.P.; Huang, S.J. Effects of business greening and green IT capital on business competitiveness. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.C.; Maulida, G.A.; Perdana, B.P.; NA, M.A.; Hendrawan, R. The Impact of Commercial Development of the Reservation Environment in the German Investigation. ESE Int. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2018, 1, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, M.A.; Rondinelli, D.A. Proactive corporate environmental: A new industrial revolution. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, L.C.; Klassen, R.D. Integrating environmental issues into the mainstream: An agenda for research in operations management. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity: Sources and consequence. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welford, R. Corporate Environmental Management: Systems and Strategies; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sezen, B.; Çankaya, S.Y. Green Supply Chain Management Theory and Practices. In Operations and Service Management: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D. Environmental Consciousness: An Empirical Study. J. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Weng, C.S. The influence of environmental friendliness on green trust: The mediation effects of green satisfaction and green perceived quality. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10135–10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M. Improving firm environmental performance and reputation: The role of employee green teams. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M. What Drives Green Product Development and How do Different Antecedents Affect Market Performance? A Survey of Italian Companies with Eco-Labels. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1144–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.P.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, H.Y. Simplified neutrosophic linguistic multi-criteria group decision-making approach to green product development. Group Decis. Negotiat. 2017, 26, 597–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, D.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, H. Does Seeing “Mind Acts Upon Mind” Affect Green Psychological Climate and Green Product Development Performance? The Role of Matching Between Green Transformational Leadership and Individual Green Values. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, B. Product innovation and market shaping: Bridging the gap with cognitive evolutionary economics. Indraprastha J. Manag. 2016, 4, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F.A. The Sensory Order: An Inquiry into the Foundations of Theoretical Psychology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Erkut, B.; Kaya, T. Knowledge Generation for Regional Competitive Advantage. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Barcelona, Spain, 7–8 September 2017; Volume 1, pp. 310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Govindarajulu, N. A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Bus. Soc. 2009, 48, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Bateman, T. Individual environmental initiative: Championing natural environmental issues in U.S. Business Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 548–570. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, M.D.; Newman, W.R.; Johnson, P. Linking operational and environmental improvement through employee involvement. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 30, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A. Organizing support for employees: Encouraging creative ideas for environmental sustainability. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Killmer, A.B. Corporate greening through prosocial extrarole behaviours—A conceptual framework for employee motivation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, L.; Stubbs, M. Termites and champions: Case comparisons by metaphor. Green. Manag. Int. 2000, 29, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Chen, Y. Linking environmental management practices and organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3552–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Greening the corporation through organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Balice, A.; Dangelico, R.M. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Smith, J.S.; Gleim, M.R.; Ramirez, E.; Martinez, J.D. Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiyeh, S.; Adaku, E.; Amoako-Gyampah, K.; Asante-Darko, D.; Amoatey, C.T. Environmental management practices, operational competitiveness and environmental performance: Empirical evidence from a developing country. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 29, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxfield, S. Reconciling corporate citizenship and competitive strategy: Insights from economic theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Whetten, D.A. Research in Organizational Behavior; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M. Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 517–554. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, P.; Whetten, D.A. Members’ identification with multiple-identity organization. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B. Identity, image and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 370–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraie, M.S.; Rad, F.M. Mediator Role of the Organizational Identity Green in Relationship between Total Quality Management and Perceived Innovation with Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2015, 4, 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Feather, N.T.; Rauter, K.A. Organizational citizenship behaviours in relation to job status, job insecurity, organizational commitment and identification, job satisfaction and work values. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, O.; Van Dick, R.; Wagner, U.; Stellmacher, J. When teachers go the extra mile: Foci of organisational identification as determinants of different forms of organisational citizenship behaviour among schoolteachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 73, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Miao, Q.; Hofman, P.S.; Zhu, C.J. The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D.C.; Faerman, S. Government employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: The impacts of public service motivation, organizational identification, and subjective OCB norms. Int. Public Manag. J. 2017, 20, 531–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Lou, J.H.; Eng, C.J.; Yang, C.I.; Lee, L.H. Organizational citizenship behaviour of men in nursing professions: Career stage perspectives. Collegian 2018, 25, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, B. The Emergence of the ERP Software Market between Product Innovation and Market Shaping. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, U. Competition as an Ambiguous Discovery Procedure: A Reappraisal of F. A. Hayek’s Epistemic Liberalism. Econ. Philos 2013, 29, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Van Schie, E.C.M. Foci and correlates of organizational identification. J. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 79, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, G. On the various and changing meaning of organizational membership: A field study of organizational identification. Commun. Monogr. 1983, 50, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product innovation performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green Innovation Strategy and Green Innovation: The Roles of Green Creativity and Green Organizational Identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Product development: Past research, present findings, and future directions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.; Ulrich, K.T. Product development decisions: A review of the literature. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D. Understanding new markets for new products. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organ. Dyn. 1991, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.P.; O’Connor, G.C.; Peters, L.S.; Morone, J.G. Managing discontinuous innovation. Res. Technol. Manag. 1998, 41, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D.M.; Goethals, G.R. Individual and Group Goals; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.J.; George, G.; Van den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Senior team attributes and organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of transformational leadership. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 982–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordan, J.C. “That Vision Thing” the Key to Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Res. Technol. Manag. 1995, 38, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational mindfulness and mindful organizing: A reconciliation and path forward. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosik, J.J.; Kahai, S.S.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and dimensions of creativity: Motivating idea generation in computer-mediated groups. Creat. Res. J. 1998, 11, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The Social Psychology of Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Rich, G.A. Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larwood, L.; Falbe, C.M.; Kriger, M.P.; Miesing, P. Structure and meaning of organizational vision. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 740–769. [Google Scholar]

- Ayag, Z. An integrated approach to evaluating conceptual design alternatives in a new product development environment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 687–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, J.A.; Kouvelis, P.; Mallick, D.N. Design strategy and its interface with manufacturing and marketing: A conceptual framework. J. Oper. Manag. 1991, 10, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive environmental strategies: When does it pay to be green? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R. The roles of OCB and automation in the relationship between job autonomy and organizational performance: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Asencio, R.; Seely, P.W.; DeChurch, L.A. How organizational identity affects team functioning: The identity instrumentality hypothesis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1530–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, D.W.; LePine, J.A. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Job Engagement: “You Gotta Keep’em Separated!”. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P. Organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: Measurement and validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Steger, U. The roles of supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee Eco-initiatives at leading-edge European companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.L. Lean and green: The move to environmentally conscious manufacturing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 39, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.J.; Boiral, O.; Lagace´, D. Environmental commitment and manufacturing excellence: A comparative study within Canadian industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.Y. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioppolo, G.; Cucurachi, S.; Salomone, R.; Saija, G.; Shi, L. Sustainable local development and environmental governance: A strategic planning experience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry | Number of Firm | Percent of Sample (%) | Size of Firm | Number of Samples | Percent of Sample (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| electronics | 45 | 9.47% | less than 100 people | 143 | 30.11% |

| information services | 50 | 10.53% | |||

| components manufacturing | 60 | 12.63% | |||

| computer and peripheral products | 80 | 16.84% | 100–500 | 155 | 32.63% |

| electronic products and components | 63 | 13.26% | |||

| communication equipment manufacturing | 24 | 5.05% | |||

| biotech and health care | 30 | 6.32% | 500–1000 | 120 | 25.26% |

| machinery and equipment manufacturing | 20 | 4.21% | |||

| software industries | 30 | 6.32% | more than 1000 people | 57 | 12% |

| among others | 73 | 15.37% | |||

| Total | 475 | 100% | Total | 475 | 100% |

| Constructs | Mean | Standard Deviation | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. GOI | 5 | 0.8199 | 0.842 | |||

| B. GSV | 5.167 | 1.0309 | 0.380 ** | 0.83 | ||

| C. OCBE | 4.6 | 1.037 | 0.547 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.837 | |

| D. GPDP | 5 | 0.699 | 0.646 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.637 ** | 0.764 |

| Constructs | Number of Items | Number of Factors | Accumulation Percentage of Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOI | 6 | 1 | 76.438% |

| GSV | 4 | 1 | 75.776% |

| OCBE | 10 | 1 | 75.825% |

| GPDP | 5 | 1 | 69.255% |

| Constructs | Item Number | Items | λ | Cronbach’s α | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOI | GOI01 | top managers, middle managers, and employees of the organization are proud of its history regarding environmental management and protection. | 0.844 | 0.936 | 0.71 | 0.842 |

| GOI02 | top managers, middle managers, and employees of the organization are proud of its environmental objectives and missions. | 0.881 *** | ||||

| GOI03: | top managers, middle managers, and employees think that the organization has maintained a significant position for environmental management and protection. | 0.808 *** | ||||

| GOI04 | top managers, middle managers, and employees of the organization think that the organization has formulated well-defined environmental objectives and missions. | 0.837 *** | ||||

| GOI05 | top managers, middle managers, and employees of the organization are knowledgeable about its environmental tradition and culture. | 0.858 *** | ||||

| GOI06 | top managers, middle managers, and employees of the organization identify that it provides considerable attention to environmental management and protection. | 0.825 *** | ||||

| GSV | GSV01 | A commonality of environmental goals exists in the company. | 0.754 | 0.897 | 0.689 | 0.83 |

| GSV02 | A total agreement on the strategic environmental direction of the organization. | 0.764 *** | ||||

| GSV03 | All members in the organization are committed to the environmental strategies. | 0.892 *** | ||||

| GSV04 | Employees of the organization are enthusiastic about the collective environmental mission of the organization. | 0.898 *** | ||||

| OCBE | OCBE01 | During work, I weigh my actions before doing something that could affect the environment. | 0.832 | 0.964 | 0.70 | 0.837 |

| OCBE02 | I voluntarily conduct environmental actions and initiatives in my daily activities at work. | 0.865 *** | ||||

| OCBE03 | I make suggestions to my colleagues about ways to effectively protect the environment, even when it is not my direct responsibility. | 0.839 *** | ||||

| OCBE04 | I actively participate in environmental events organized in and/or by the organization. | 0.80 *** | ||||

| OCBE05 | I stay informed about my environmental initiatives of the organization. | 0.821 *** | ||||

| OCBE06 | I undertake environmental actions that contribute positively to the image of my organization. | 0.828 *** | ||||

| OCBE07 | I volunteer for projects, endeavors, or events that address environmental concerns in my organization. | 0.858 *** | ||||

| OCBE08 | I spontaneously give my time to help my colleagues take the environment into account in their actions at work. | 0.826 *** | ||||

| OCBE09 | I encourage my colleagues to adopt environmentally conscious behavior. | 0.806 *** | ||||

| OCBE10 | I encourage my colleagues to express their ideas and opinions on environmental concerns. | 0.887 *** | ||||

| GPDP | GPDP01 | The project of GPD contributes significant revenues to the organization. | 0.77 | 0.888 | 0.583 | 0.764 |

| GPDP02 | the project invents outstanding GPs. | 0.766 *** | ||||

| GPDP03 | the project continues to improve its development processes over time. | 0.801 *** | ||||

| GPDP04 | The project is more creative in GPD than its competitors. | 0.74 *** | ||||

| GPDP05 | The project can achieve its aims in GPD. | 0.739 *** |

| Hypothesis | Proposed Effect | Path Coefficient | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | + | 0.396 *** | H1 is supported |

| H2 | + | 0.488 *** | H2 is supported |

| H3 | + | 0.581 *** | H3 is supported |

| H4 | + | 0.113 * | H4 is supported |

| H5 | + | 0.356 *** | H5 is supported |

| Point Estimation | Product of Coefficients | Bootstrapping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | ||||||

| S.E. | Z | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| Standardized Total Effect | |||||||

| GOI -> GPDP | 0.319 | 0.063 | 5.063 *** | 0.201 | 0.444 | 0.204 | 0.449 |

| GSV -> GPDP | 0.629 | 0.059 | 10.661 *** | 0.503 | 0.734 | 0.505 | 0.736 |

| Standardized Indirect Effect | |||||||

| GOI -> GPDP | 0.207 | 0.079 | 2.62 ** | 0.075 | 0.393 | 0.068 | 0.378 |

| GSV -> GPDP | 0.141 | 0.042 | 23.8 *** | 0.067 | 0.236 | 0.052 | 0.219 |

| Standardized Direct Effect | |||||||

| GOI -> GPDP | 0.113 | 0.107 | 1.06 | −0.114 | 0.303 | −1.02 | 0.315 |

| GSV -> GPDP | 0.488 | 0.084 | 5.81 *** | 0.313 | 0.643 | 0.326 | 0.657 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, T.-W.; Chen, F.-F.; Luan, H.-D.; Chen, Y.-S. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030617

Chang T-W, Chen F-F, Luan H-D, Chen Y-S. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030617

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Tai-Wei, Fei-Fan Chen, Hua-Dong Luan, and Yu-Shan Chen. 2019. "Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030617

APA StyleChang, T.-W., Chen, F.-F., Luan, H.-D., & Chen, Y.-S. (2019). Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability, 11(3), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030617