Local Governance and Labor Organizations on Artisanal Gold Mining Sites in Burkina Faso

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Artisanal Mining

2.2. Mining in Burkina Faso

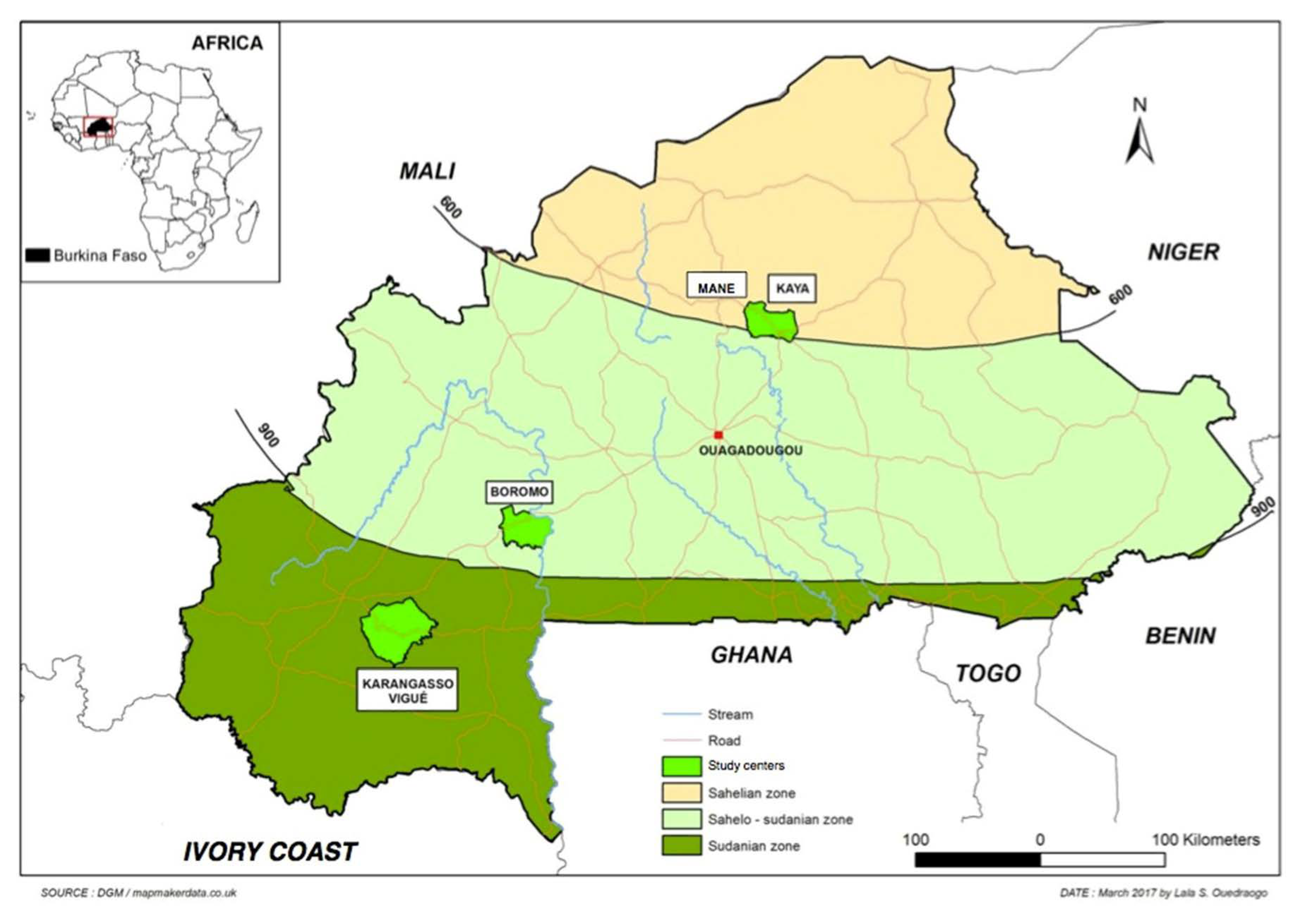

3. Methodology of the Study

3.1. Attributes of the Physical World

3.2. Objectives

3.3. Analytical Framework

- Artisanal gold may be considered a common resource since it is both a rival and a non-excludable good [65]. Specifically, gold is a rival good because, when artisanal miners extract it from the ground, it is no longer available to others. Furthermore, it is difficult to exclude people from accessing it since gold can be illegally mined without authorization.

- Artisanal gold mining communities can manage their gold resources without leading to a tragedy of commons as suggested by Hardin [21].

3.4. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Attributes of the Communities

4.2. Action Arena

4.2.1. Working Rules, Positions and Participants

Boundary Rules

Position Rules

Scope Rules

Choice Rules

Aggregation Rules

Information Rules

Payoff Rules

4.2.2. Outcomes

- Outcome 1: Gold is discoveredCertain factors determine whether gold is found. For instance, to avoid project delays, there must be a certain level of cohesion among group members. Once gold is discovered, an owner’s financial obligations will determine who benefits from it. Pit owners sometimes lend money to each other or to gold purchasers [68]. If an owner who borrows money discovers gold, the lender will obtain a share of the profits proportional to the amount invested, which is known as selection on gold mining camps. As pointed out by Mégret [71], this term may be used for profit sharing. For instance, if the lender invested half of the required amount, he will get half the profits. In some cases, even after gold has been discovered, the revenue generated is not enough to cover expenses and the pit owner can end up with significant debt. In some cases, miners find gold but are evicted by the government officials. For instance, in Diosso, 70% of the sample admitted that relations had been tense with government officials affiliated with the regime of Blaise Campaore that collapsed in 2014. Miners were forced to sell their gold for USD 25 per gram instead of the market value of USD 42. If they refused, police officers would beat them and collect their gold without compensation; in such cases, pit owners lost their entire investment. In both cases, the gold dust or nugget is eventually sold either in the camp to individual buyers/sellers or outside of the camp in which case miners may be robbed on their way and eventually lose their gold.

- Outcome 2: No gold is discovered, loss of part or entire investmentWhile many artisanal miners have prospered, others have lost all or part of their investment and some have even left the sector after incurring significant debts. Usually, this occurs when pits collapse and become too dangerous to work in or when an owner runs out of money.

4.3. Performance

- Productivity: In the context of our study, productivity refers to the quantity of gold extracted from each mine site. As we mentioned previously, the informal nature of artisanal mining makes it difficult to accurately estimate this amount that is coherent with the statement of Heemskerk [6]. Surveyed workers, however, were asked if they believed finding gold depended on some specific criteria. They pointed out luck, hard work or financial resources. According to the results, most respondents (60%) conceded that luck was the most important determinant of performance followed by work and financial resources (Table 5).

- Sustainability: Sustainability is usually measured through three different indicators namely economic, environmental and social [72]. Moreover, the same criteria can be used to evaluate the sustainability of artisanal mining [19,73]. This indicator will be discussed in Section 4.4.

- Poverty reduction: The results of our fieldwork indicate that small-scale mining has had a positive impact on poverty alleviation. As Table 5 shows, at each camp visited, more than 90% of respondents agreed that mining had improved their economic situation. Miners reported having more money for things such as paying for school costs, building a house or buying a motorcycle. Studies in Burkina Faso and Mali have shown that such types of purchases are clear indicators of improvements in household welfare [3,8,11,41,53]. As we have noticed during the field visit, artisanal mining also creates positive spillover effects for neighboring villages (Kien near Diosso, Arba near Zincko for instance) as traditional homes made from mud and straw are replaced by ones with steel roofing. The same conclusions were drawn by Mégret [53] and Teschner [41].

4.4. Sustainable Development Indicators

4.4.1. Social Indicators

- EmploymentAll respondents agreed that artisanal mining had created employment opportunities for both local and migrants communities. For local communities, the establishment of a mining camp provide opportunities for people to be hired as laborers (diggers, crushers, mill operators...) on camps while women pursue petty trade as sale of food and water [9,11,53,71]. Furthermore, nearby farmers gain revenue by selling agricultural products. Other non-miner migrants hold commercial shops from clothing stores, to electronic and, most importantly, movie theaters that create a lively environment where miners may relax overnight similar to the findings of Mégret [71]. Finally, once in a while, when pit owners retrieve gold, they are so generous that they would give money to some lucky inhabitants.

- Health and safetySeveral health and safety issues were reported on the sites. Dust from the pits was causing respiratory problems because workers did not have proper personal protective equipment; and injuries and deaths had occurred due to collapsing shafts as discussed by Werthmann [3], Jaques et al. [55]. Since there were no medical centers on site, miners resort to self-treatment by purchasing usually prohibited medications from medicine vendors. In line with Mégret [53] work in Kampti, miners on the study camps use some drugs and adulterated liquor in order to face the hardship of the work that eventually degrade their health condition.

- Child laborChildren are frequently seen on site during our field trip. Nevertheless, all respondents agree that they are prohibited to enter mining pits at less than 17 years of age. They generally cook for the miners (in which case they are called bantaris). These children do not come from the nearest villages and their origin is not always known by the pit owners. They will live on the camps and taken care of by the pit owners as any other laborer while doing the cook. Apart from these ones, children from the nearby villages would work on site daily, as ore crushers or sellers. This is opposed to the findings of the investigation conducted by Gueniat and White [64], which revealed that a great deal of gold smuggled through Togo towards Switzerland is extracted by children in extreme working conditions. It is important to note that the reliability of this research is limited as respondents may not admit to illegal activities.

- Relationships with local communitiesIn Diosso, customary authorities were not satisfied with the earnings that they were receiving from pit owners, and complained that mining was causing local prices to increase and polluting the drinking water. Furthermore, governance and politics were at stake in Diosso. In fact, as migration is sustained over time, at one point, the population of migrants (Mossi) is greater than that of the indigenous. Thus, during elections, migrants tend to vote for a migrant that would likely enact politics favourable to artisanal mining at the expense of the indigenous communities. In such context, indigenous communities contested the results leading to extreme violence between migrants and indigenous communities [74]. In Siguinoguin, relationships were tense between miners and the local population over nuisance issues, the death of livestock due to water contamination from the mine, destruction of trees among others [11,55]. Disputes are settled before elders and/or customary authorities. If no resolution is reached, the case is handed over to the police. In contrast, in Zincko, relations were harmonious since the miners hail from the local community. Basically, artisanal mining culturally dismantles the social patterns in rural areas. First, at a local level, land tenure arrangements in artisanal mining areas generate revenue for land owners. Then, local communities would be tempted to base their revenue only on this new source. As we know, this source is not sustained over time and that lead to structural implication for their offspring. Second, in some cases, due to the highest revenue earned by young miners, they do not abide by the customs which include respect for elders and willingness to pursue farming. Second, there is a risk of breaking up between former miners that had been successful and the newcomers that would fail due to a potential depletion of the resource.

4.4.2. Economic Indicators

- Revenue sharing with local communitiesPit owners reach informal agreements with customary authorities whereby they consent to hand over part of their revenues. In Diosso, pit owners give one tenth of their bags to customary authorities and in Zincko the same proportion of bags is delivered to the landowner. In Siguinoguin, pit owners also hand over one tenth of their bags, in addition to paying a plot issuance fee, which costs between USD 20 and USD 30 as reported by Werthmann [3]. Regarding the investment in local communities, our survey reveals that, in general, in the villages of Diosso, Zincko and Siguinoguin miners do not contribute to the local development of the village (i.e., contribute to build schools, hospitals and other infrastructure). However, the head of the miners’ union has reported in September 2016 that the union has provided houses for teachers, ambulances, 14 water pumps, two water towers and 32 motorcycles to village representatives of the province of Bam [69].

4.4.3. Environmental Indicators

- EnvironmentMiners cut down trees and use them to prevent the pits from collapsing or to create a pulley system for lifting miners and materials as stated in Mégret [71] and Werthmann [3]. Sometimes, this destruction is a source of tensions between miners and local communities especially in the village of Siguinoguin. The same case is portrayed by Werthmann [11] as gold discovery in the village of Dimouan attracted many miners from around Burkina Faso that did not hesitate to cut some protected trees such as karite. Even though most actions of miners are not favourable for the environment, we have observed that the use of reusable bags to store gold ore, assemble houses or toilets; gathering places for worship or socialization are positive for sustainability. Adding to the destruction of trees is the fact that mine pits that are no longer useful are usually not filled in, which prevents the land from being converted back to agricultural use (in Diosso and Siguinoguin). We believe that finding ways to do so will considerable impede the negative environmental impacts of artisanal mining. For near-surface artisanal gold mining, pits can still be converted back to agriculture use (in Zincko). Thus far, the question that remains is whether industrial mining negative impacts are not greater than the artisanal mines impacts because many studies focus on the latter overlooking the former.

- Air, noise and water pollutionSmall-scale mining uses mercury to amalgamate gold. The amalgam gives the gold a grayish color, which is removed through heating. However, the heat treatment process releases gases that are dangerous to human health. Dynamite is used at all three sites when pits reach 10 m deep and digging is too difficult as described by Mégret [71]. This creates noise pollution for residents of the surrounding areas. The quantity of water used to remove gold is small compared to what is collected from the underground during digging. This water is reused in several ways. First, miners use it to wash the gold ore. Second, they use it for baths. Sometimes, the water is just pumped out of the pits and spilled on the ground with no use. One might be tempted to ask why this water is not used for agricultural purposes. Water from the mines is often polluted since workers sometimes stay in the pits for several days and defecate in the open air. As a result, farmers often prefer not to use it for agricultural purposes (this was especially the case in Diosso). This is not solely the issue here as cyanide used by miners is carried by heavy rains from the camp to nearby areas, resulting in the death of livestock from water contamination. Such situation leads to dispute between miners and agropastoralist communities as mentioned in Jaques et al. [55]. One way of dealing with this waste water would be to organize some methods of treating it in order to deliver drinkable water for populations and usable water for agriculture.

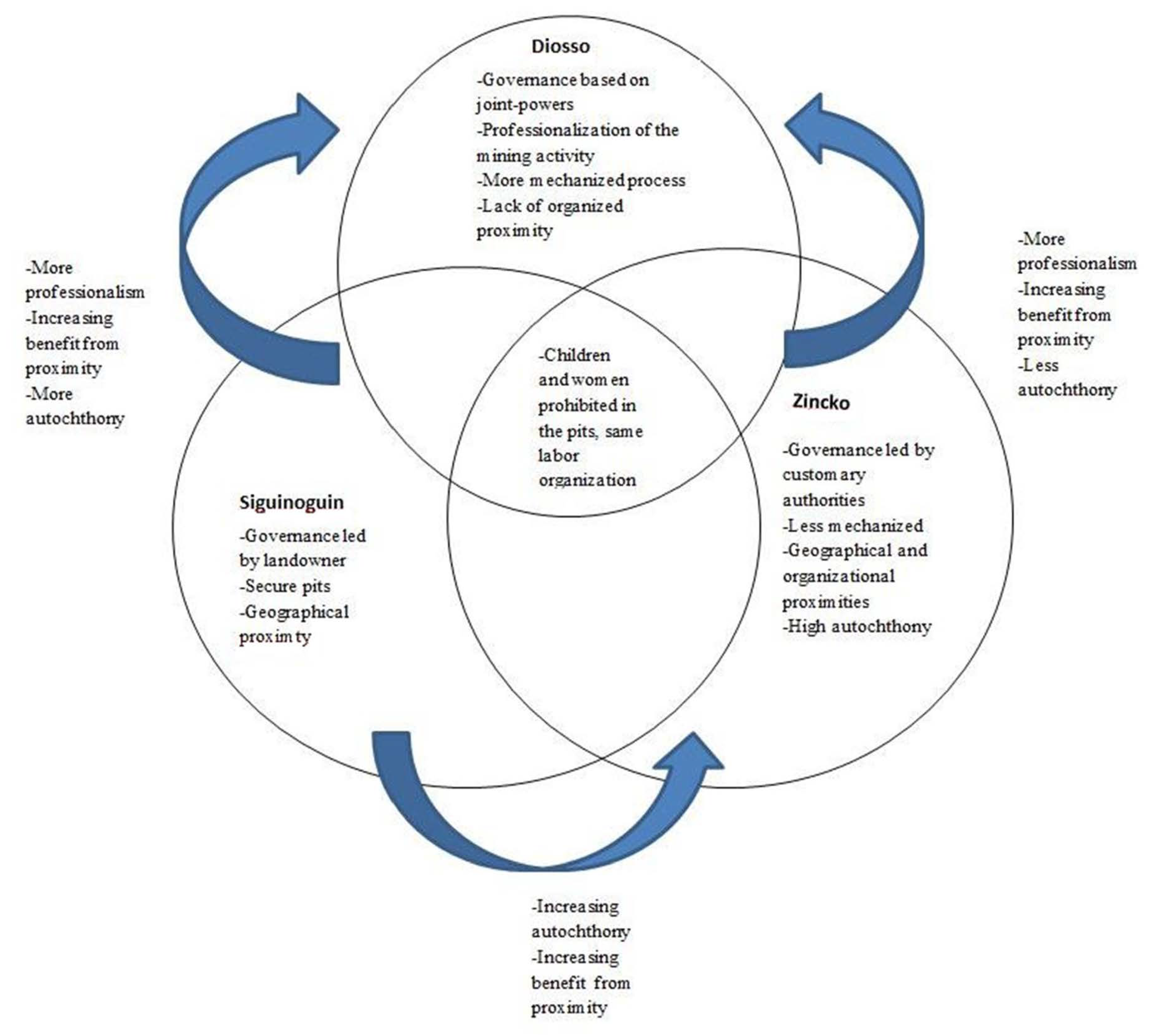

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Labonne, B. Artisanal mining: An economic stepping stone for women. Nat. Resour. Forum 1996, 20, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grätz, T. Mining Frontiers in Africa: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives. In Gold Mining in the Atakora Mountains in Benin: Exchange Relations in a Volatile Economic Field; Rüdiger Köppe Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2012; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, K. The drawbacks of privatization: Artisanal gold mining in Burkina Faso 1986–2016. Resour. Policy 2017, 52, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, N. Social and Labour Issues in Small-Scale Mines: Report for Discussion at the Tripartite Meeting on Social and Labour Issues in Small-Scale Mines, Geneva, 1999; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Mining Together: Large-Scale Mining Meets Artisanal Mining—A Guide for Action; Technical Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk, M. Collecting data in artisanal and small-scale mining communities: Measuring progress towards more sustainable livelihoods. In Natural Resources Forum; Wiley Online Libary: Oxford, UK, 2005; Volume 29, pp. 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstael, S. The Persistence of Informality: Perspectives on the Future of Artisanal Mining in Liberia. Futures 2014, 62, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaré, O.; Mundler, P.; Ouedraogo, L. Institutions informelles et gouvernance de proximité dans l’orpaillage artisanal. Un cas d’étude au Burkina Faso. Revue Gouvernance 2016, 13, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthmann, K. Translocality: The study of globalising processes from a southern perspective. In ‘Following the Hills’: Gold Mining Camps as Heterotopias; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, M.M.; Scoble, M.; McAllister, M.L. Mining with communities. In Natural Resources Forum; Wiley Online Library: Oxford, UK, 2001; Volume 25, pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, K. Histoire du Peuplement Et Relations Interethniques au Burkina Faso. In Ils Sont Venus Comme une Nuée de Sauterelles–Chercheurs d’or au Burkina Faso; Karthala: Paris, France, 2003; Volume 97, p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Banchirigah, S. How reforms have fuelled the expansion of artisanal mining? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Resour. Policy 2006, 31, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitula, A.G. The environmental and socio-economics impacts of mining on local livelihoods in Tanzania: A case of Geita District. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maconnachie, R.; Binns, T. Farming miners or mining farmers: Diamond mining and rural development in post-conflict Sierra Leone. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garforth, C.; Hilson, G. Everyone is now concentrating on the mining: Drivers and implications of rural economic transition in the Eastern Region of Ghana. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 49, 348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Pijpers, R. Crops and Carats: Exploring the Interconnectedness of Mining and Agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. Futures 2014, 62, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, J.; Veiga, M.M.; Beinhoff, C. Women and Artisanal Mining: Gender Roles and the Road Ahead. In The Socio-Economic Impacts of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in Developing Countries; AA Balkema, Sweets Publishers: Hurst, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Telmer, K.H.; Veiga, M.M. World emissions of mercury from artisanal and small-scale gold mining. In Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 131–172. [Google Scholar]

- Azapagic, A. Developing a framework for sustainable development indicators for the mining and minerals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 630–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschakert, P.; Singha, K. Contaminated Identities: Mercury and Marginalization in Ghana’s Artisanal Mining Sector. Geoforum 2007, 38, 1304–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common Pool Resources; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, T.M. Parks, people, and forest protection: An institutional assessment of the effectiveness of protected areas. World Dev. 2006, 34, 2064–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.A. Institutional factors affecting biophysical outcomes in forest management. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2009, 28, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T.; Yandle, T. Taking institutions seriously: Using the IAD framework to analyze fisheries policy. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E. Artisanal Gold Mining at the Margins of Mineral Resource Governance: A Case from Tanzania. Dev. S. Afr. 2008, 25, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. Small scale mining, poverty and economic development in SSA: An overview. Resour. Policy 2009, 34, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclin, B.J.; Kelly, J.T.; Perks, R.; Vinck, P.; Pham, P. Moving to the mines: Motivations of men and women for migration to artisanal and small-scale mining sites in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Resour. Policy 2017, 51, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D.F.; Jønsson, J.B. Gold digging careers in Rural East Africa: Small-Scale Miners’ Livelihood Choices. World Dev. 2010, 38, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. ‘Once a miner, always a miner’: Poverty and livelihood diversification in Akwatia, Ghana. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthmann, K. Working in a Boom-Town: Female Perspectives on Gold-Mining in Burkina Faso. Resour. Policy 2009, 34, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaldi di Balme, L.; Lanzano, C. Gouverner l’éphémére. étude sur l’organisation technique et politique de deux sites d’orpaillage Bantara et Gombélèdougou, Burkina Faso. Étude Récit 2014, 37, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Noetsaller, R. Small Scale Mining: A Review of the Issues; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, K. Cowries, Gold and ‘Bitter money’. Gold-mining and notions of ill-gotten wealth in Burkina Faso. Paideuma 2003, 49, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, K. Gold Mining and Jula Influence in Precolonial Southern Burkina Faso. J. Afr. Hist. 2007, 48, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondeyne, S.; Ndunguru, E. Artisanal mining in Central Mozambique: Policy and environmental issues of concern. Resour. Policy 2009, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchirigah, S.; Hilson, G. De-agrarianization, re-agrarianization and local economic development: Re-orienting livelihoods in African artisanal mining communities. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Okoh, G. Poverty and livelihood diversification: Exploring the linkages between smallholder farming and artisanal mining. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Teschner, B.A. “Orpaillage Pays for Everything”: How Artisanal Mining Supported Rural Institutions Following Mali’s Coup d’état. Futures 2014, 62, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. Land use competition between small- and large scale miners: A case study of Ghana. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyame, F.; Blocher, J. Influence of land tenure practises on artisanal mining activity in Ghana. Resour. Policy 2010, 35, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashwira, M.R.; Cuvelier, J.; Hilhorst, D.; van der Haar, G. Not only a man’s world: Women’s involvement in artisanal mining in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Resour. Policy 2014, 40, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Osei, L. Tackling Youth Unemployment in sub-Saharan Africa: Is There a Role for Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining? Futures 2014, 62, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luning, S. World of debts: Interdisciplinary perspectives on gold mining in West Africa. In Beyond the Pale of Property: Gold Miners Meddling with Mountains in Burkina Faso; Rozenberg Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann, K. The president of gold diggers: Sources of power in a gold mine in Burkina Faso. Ethnos 2003, 68, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaré, O. Rôle de L’orpaillage Dans le Système D’activités des Ménages en Milieu Agricole: Cas de la Commune Rurale de Gbomblora Dans la Région Sud-Ouest du Burkina Faso. Master’s Thesis, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Di Balme, L.A.; Lanzano, C. Entrepreneurs de la frontière: Le role des comptoirs prives dans les sites d’extraction artisanale de l’or au Burkina Faso. Polit. Afr. 2013, 3, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiethega, J.B. L’or de la Volta Noire; Centre de Recherches Africaines: Paris, France, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bantenga, M. L’or des Régions de Poura et de Gaoua: Les Vicissitudes de L’exploitation Coloniale, 1925–1960. Int. J. Afr. Hist. Stud. 1995, 28, 563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Amutabi, M.; Lutta-Mukhebi, M. Gender and Mining in Kenya: The Case of the Mukibira Mines in the Vihiga District. Jenda J. Cult. Afr. Women’s Stud. 2001, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mégret, Q. Déjouer la mort en Afrique. In L’or “mort ou vif ” L’orpaillage en pays Lobi Burkinabé; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.; Belem, G.; Coulibaly, V.N. Poverty Reduction in Africa: On Whose Development Agenda? Lessons from Cotton and Gold Production in Mali and Burkina Faso; Research Paper; Oxfam America: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, E.; Zida, B.; Billa, M.; Greffié, C.; Thomassin, J.F. Small-Scale Mining, Rural Subsistence and Poverty in West Africa; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Luning, S. Small scale mining, rural subsistence and poverty in West Africa. In Artisanal Gold Mining in Burkina Faso: Permits, Poverty and Perceptions of the Poor in Sanmatenga, the ‘Land of Gold’; Practical Action Publisher: Rugby, UK, 2006; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Luning, S. Traditions on the Move. Essays in Honor of Jarich Oosten. In Gold in Burkina Faso: A Wealth of Poison and Promise; Rozenberg: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2009; pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Luning, S. Dilemmas Of Development. In Gold Mining in Sanmatenga, Burkina Faso: Governing Sites, Appropriating Wealth; African Studies Center: The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.K.; Loxley, J. Structural Adjustment in Africa; MacMillan: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.; Prémont, M.C. What is behind the search for social acceptability of mining projects? Political economy and legal perspectives on Canadian mineral extraction. Min. Econ. 2017, 30, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueye, D. Small-Scale Mining in Burkina Faso; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bossom, R.; Varon, B. L’industrie Minière Dans le Tiers Monde; Banque Mondiale: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B. Mining in Africa: Regulation and Development; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gueniat, M.; White, N. A Golden Racket: The True Source of Switzerland’s “Togolese” Gold; Technical Report; Berne Declaration: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saldarriaga-Isaza, A.; Villegas-Palacio, C.; Arango, S. The public good dilemma of a non-renewable common resource: A look at the facts of artisanal gold mining. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana, J. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grãtz, T. Les Frontières de L’orpaillage en Afrique Occidentale. Autrepart 2004, 2, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOB. Mines au Burkina: Le Syndicat des Orpailleurs Artisanaux Souhaite une “RéElle Politique D’Encadrement” du Secteur (ITW, Responsable). Available online: http://news.aouaga.com/h/102493.html (accessed on 30 November 2017).

- Lentz, C. Land, Mobility, and Belonging in West Africa; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mégret, Q. Afriques au figuré: Images migrantes. In Comment Faire “Son Cinema” Dans un Camp Minier du Sud Ouest Burkinabé; Archives Contemporaines: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: “Our Common Future”; Technical Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kumah, A. Sustainability and gold mining in the developing world. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danoaga, D. Election du Maire, 2 Morts a Karangasso-Vigue, Sidwaya. Available online: http://www.sidwaya.bf/m-11947-election-du-maire-2-morts-a-karangasso-vigue-.html (accessed on 26 December 2017).

- Shaw, A.T.; Gilly, J.P. On the analytical dimension of proximity dynamics. Reg. Stud. 2000, 34, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A. Jalons pour une analyse dynamique des Proximités. Revue d’Économie Régionale Urbaine 2010, 3, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions (Province) | Commune | Population (Number of Villages) | Creation of the Mining Camp | Number of Pits (Miners) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southwestern (Houet) | Karangasso Vigue (Diosso) | 75,481 (25) | 2006 | 150–250 (3000–5000) |

| Boucle du Mouhoun (Bale) | Boromo (Siguinoguin) | 29,845 (8) | 2009 | 100–150 (500–750) |

| North-Central (Sanmatenga) | Mane (Zincko) | 46,484 (44) | 1987 | 100–150 (500–750) |

| Attributes of the Context | Attribute Forms |

|---|---|

| Attributes of the physical world | Geographical area: map, spatial characteristics |

| Quantity: changes in resource levels over time | |

| Attributes of the community | Socio-economic: age, household size, sex, education |

| Culture: ethnicity, cultural background | |

| Action arena: analyse and predict behaviors within the organisatonal setting | Actors: stakeholders in the mining sector |

| Action situation: defines the context in which interactions occur among the different participants | |

| Outcomes: observed results from interactions among participants | |

| Working rules: formal/informal | Boundary rules: physical limit of the resource |

| Position rules: change from one position to another within the organizational setting | |

| Scope rules: terms of use for the resource | |

| Choice rules: monitoring procedures | |

| Aggregation rules: permission and prevention | |

| Information rules: shared and hidden information | |

| Payoff rules: rules related to sanctions | |

| Performance assessment | Productivity: assess performance using productivity indicators |

| Sustainability: assess performance using sustainable development indicators | |

| Poverty reduction: assess performance in terms of poverty reduction |

| Variables | Artisanal Gold Mining Sites | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diosso | Siguinoguin | Zincko | |||||

| Mining Area | Non-Mining Area | Mining Area | Non-Mining Area | Mining Area | Non-Mining Area | ||

| Age (in %) | <18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 |

| 18–30 | 23.1 | 0.0 | 31.8 | 0.0 | 52.5 | 0.0 | |

| 31–40 | 30.8 | 0.0 | 43.2 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 12.5 | |

| 41–50 | 33.3 | 38.5 | 9.1 | 30.0 | 15.0 | 12.5 | |

| >50 | 12.8 | 61.5 | 15.9 | 40.0 | 7.50 | 75.0 | |

| Gender (in %) | Male | 94.9 | 100.0 | 84.1 | 100 | 82.5 | 62.5 |

| Female | 5.1 | 0.00 | 15.9 | 0.0 | 17.5 | 37.5 | |

| Household size (in %) | 1–3 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 27.3 | 0.0 | 22.5 | 0.0 |

| 4–6 | 33.3 | 7.7 | 38.6 | 0.0 | 42.5 | 0.0 | |

| 7–10 | 38.5 | 92.3 | 15.9 | 20.0 | 17.5 | 12.5 | |

| >10 | 12.8 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 80.0 | 17.5 | 87.5 | |

| Education (in %) | None | 87.2 | 100 | 65.9 | 100 | 82.5 | 75.0 |

| Primary | 10.3 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 25.0 | |

| Secondary | 2.6 | 0.0 | 20.5 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.0 | |

| Ethnicity (in %) | Mossi | 74.4 | 46.1 | 79.5 | 100 | 80.0 | 100 |

| Gourmantche | 10.3 | 0.0 | 11.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Other ethnicities | 15.4 | 53.8 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | |

| Origin (in %) | North | 64.1 | 38.5 | 59.1 | 0.0 | 87.5 | 100 |

| East | 15.4 | 7.7 | 15.9 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.0 | |

| South | 5.1 | 53.8 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Other regions | 12.8 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Positions | Artisanal Gold Mining Sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diosso | Siguinoguin | Zincko | |

| Diggers (%) | 15.4 | 29.5 | 30.0 |

| Team leaders (%) | 10.2 | 4.5 | 7.5 |

| Guards (%) | 0.0 | 2.3 | 17.5 |

| Supervisors (%) | 12.8 | 2.3 | 17.5 |

| Dynamite handlers (%) | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Pit owners (%) | 53.8 | 29.5 | 25.0 |

| Warehouse owners (%) | 0.0 | 13.6 | 2.5 |

| Cyanide applicators (%) | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Buyers and sellers (%) | 0.0 | 9.1 | 2.5 |

| Mill owners/users (%) | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 |

| Winnowers (%) | 5.1 | 2.3 | 30.0 |

| Performance | Artisanal Gold Mining Sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diosso | Siguinoguin | Zincko | |

| Luck | 71.8 | 88.6 | 90.0 |

| Financial resources | 7.7 | 4.5 | 0.0 |

| Work | 20.5 | 6.8 | 10.0 |

| Impacts | Artisanal Gold Mining Sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diosso | Siguinoguin | Zincko | ||

| Reduce poverty | Yes | 94.8 | 100 | 97.5 |

| No | 5.1 | 0 | 2.5 | |

| Improve welfare conditions | Yes | 94.8 | 100 | 97.5 |

| No | 5.1 | 0 | 2.5 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouedraogo, L.S.; Mundler, P. Local Governance and Labor Organizations on Artisanal Gold Mining Sites in Burkina Faso. Sustainability 2019, 11, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030616

Ouedraogo LS, Mundler P. Local Governance and Labor Organizations on Artisanal Gold Mining Sites in Burkina Faso. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030616

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuedraogo, Lala Safiatou, and Patrick Mundler. 2019. "Local Governance and Labor Organizations on Artisanal Gold Mining Sites in Burkina Faso" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030616

APA StyleOuedraogo, L. S., & Mundler, P. (2019). Local Governance and Labor Organizations on Artisanal Gold Mining Sites in Burkina Faso. Sustainability, 11(3), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030616