Impact of Suburbanisation on Sustainable Development of Settlements in Suburban Spaces: Smart and New Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Suburbanisation in the Context of Environmental Aspects and Sustainability—Basic Problems

2.1. Suburbanisation—Possible Solutions and Challenges for the Future

2.2. Specifics of Suburbanisation in European Postsocialist States

3. Materials and Methods

- x: standardised indicator value

- xi: individual value of the municipality

- xmax: maximum value of the subindicator in the whole analysed file (among all municipalities)

- xmin: minimal value of the subindicator in the whole analysed file (among all municipalities)

- T: test criterion

- r: the correlation coefficient

- n: number of degrees of freedom

- W: critical value

- T: test criterion

- n: number of degrees of freedom

- α: level of importance

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

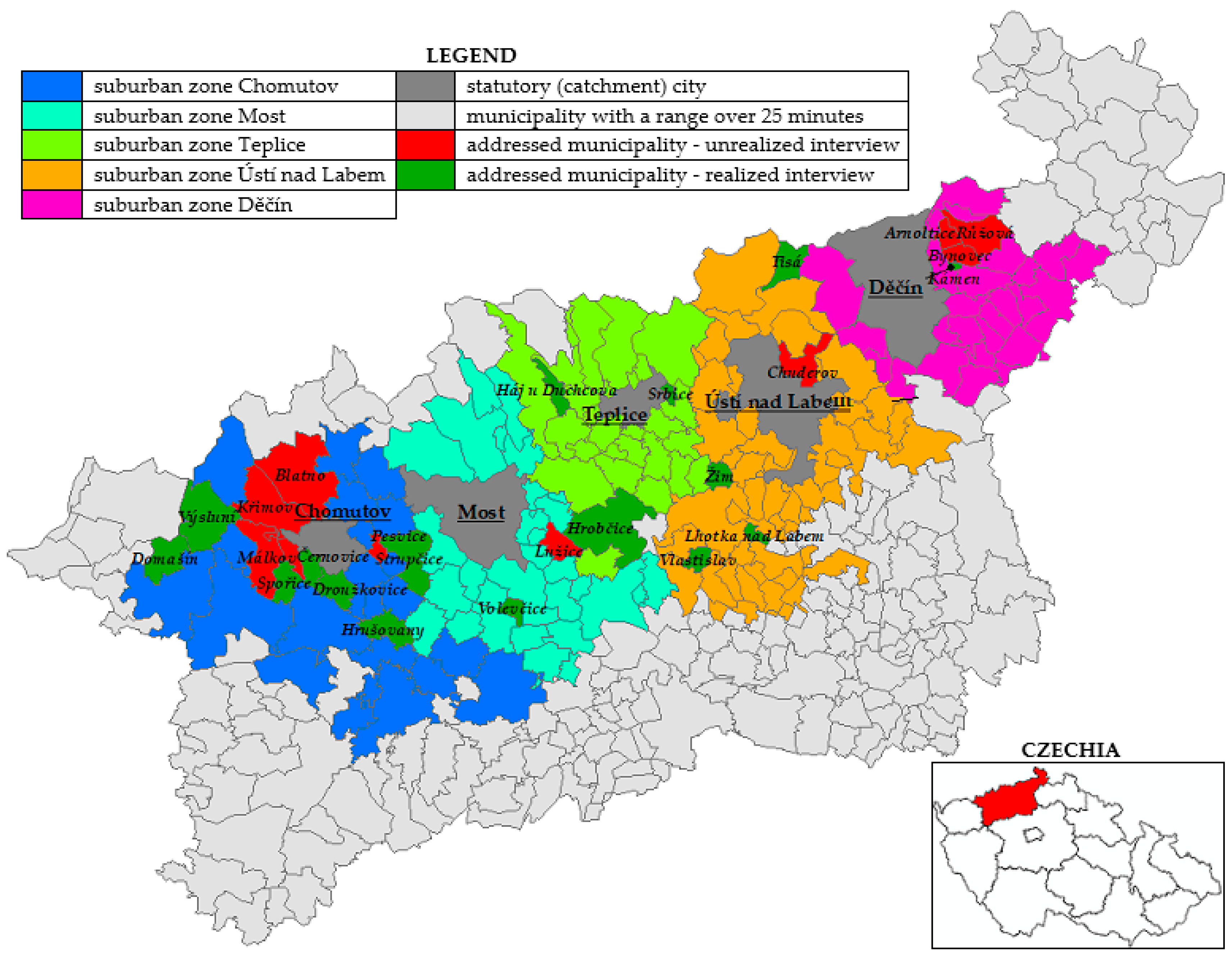

| Name of Municipality | LAU2 Code | Suburban Zone | Date of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domašín | 563048 | Chomutov | 26 June 2018 |

| Droužkovice | 563056 | Chomutov | 21 June 2018 |

| Háj u Duchcova | 567523 | Teplice | 18 June 2018 |

| Hrobčice | 567566 | Teplice | 18 June 2018 |

| Hrušovany | 563072 | Chomutov | 9 July 2018 |

| Kámen | 546453 | Děčín | 17 July 2018 |

| Lhotka nad Labem | 565113 | Ústí nad Labem | 30 July 2018 |

| Spořice | 563340 | Chomutov | 28 August 2018 |

| Srbice | 567833 | Teplice | 1 August 2018 |

| Strupčice | 563358 | Chomutov | 11 September 2018 |

| Tisá | 568309 | Ústí nad Labem | 8 June 2018 |

| Vlastislav | 565873 | Ústí nad Labem | 11 June 2018 |

| Volevčice | 546437 | Most | 26 October 2018 |

| Výsluní | 563498 | Chomutov | 26 June 2018 |

| Žim | 567884 | Ústí nad Labem | 18 July 2018 |

| Name of Municipality | LAU2 Code | Particulars of Mayor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | Time in Office | Full-Time | ||

| Domašín | 563048 | 52 years | female | 20 years | no |

| Droužkovice | 563056 | 60 years | male | 28 years | yes |

| Háj u Duchcova | 567523 | 64 years | male | 16 years | yes |

| Hrobčice | 567566 | 44 years | female | 8 years | yes |

| Hrušovany | 563072 | 50 years | male | 8 years | yes |

| Kámen | 546453 | 51 years | male | 8 years | no |

| Lhotka nad Labem | 565113 | 38 years | male | 3 years | no |

| Spořice | 563340 | 52 years | male | 8 years | yes |

| Srbice | 567833 | 56 years | male | 12 years | yes |

| Strupčice | 563358 | 40 years | male | 14 years | yes |

| Tisá | 568309 | 66 years | male | 8 years | yes |

| Vlastislav | 565873 | 54 years | female | 4 years | no |

| Volevčice | 546437 | 41 years | male | 1 year | no |

| Výsluní | 563498 | 55 years | female | 4 years | no |

| Žim | 567884 | 61 years | male | 16 years | yes |

References

- Krzysztofik, R.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Runge, A.; Spórna, T. Is the suburbanisation stage always important in the transformation of large urban agglomerations? The case of the Katowice conurbation. Geogr. Pol. 2017, 90, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X. The residential resettlement in suburbs of Chinese cities: A case study of Changsha. Cities 2017, 69, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolek, J.; Andráško, I.; Malý, J.; Zrůstová, P. Interrelated aspects of residential suburbanization and collective quality of life: A case study in Czech suburbs. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2017, 57, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T. Suburban realities: The Israeli case. CLCWeb Comp. Lit. Cult. 2019, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestorová Dická, J.; Gessert, A.; Sninčák, I. Rural and non-rural municipalities in the Slovak Republic. J. Maps 2019, 15, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R.; Addie, J.-P.D. ‘It’s not going to be suburban, it’s going to be all urban’: Assembling post-suburbia in the Toronto and Chicago regions. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 892–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vidovich, L. Suburban studies: State of the field and unsolved knots. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadewo, E.; Syabri, I.; Pradono, P. Beyond the early stage of post-suburbanization: Evidence from urban spatial transformation in Jabodetabek Metropolitan Area. Iop Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 158, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Wu, F.; Xie, X. The spatial characteristics and relationships between landscape pattern and ecosystem service value along an urban-rural gradient in Xi’an city, China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 108, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, N.A.; Wood, A.M. The new post-suburban politics? Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 2591–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, N.A.; Parsons, N. Edge urban geographies: Notes from the margins of Europe’s capital cities. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1725–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toublanc, M.; Bonin, S. The edges of the city in the making, between policy and inhabitant appropriation: Reunion island case studies. Développement Durable Territ. 2019, 10, 14503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerten, C.; Fina, S.; Rusche, K. The sprawling planet: Simplifying the measurement of global urbanization trends. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet, N.; Coste, A. Garden cities of the 21st century: A sustainable path to suburban reform. Urban Plan. 2017, 2, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, D.; Proulhac, L. The spatial dynamic of logistic activities in the French urban areas. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2016, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmes, E.; Keil, R. The politics of post-suburban densification in Canada and France. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spórna, T. The suburbanisation process in a depopulation context in the Katowice conurbation, Poland. Environ. Socio Econ. Stud. 2018, 6, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C. ‘Back to the village’: The model of urban outmigration in post-communist Romania. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, A. Russian specifics of dacha suburbanization process: Case study of the Moscow region. Econ. Soc. Chang. Facts Trends 2015, 6, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauser, J.; Stewart, W.P.; Evans, N.M.; Stamberger, L.; van Riper, C.J. Heritage narratives for landscapes on the rural–urban fringe in the Midwestern United States. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 62, 1269–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Farkas, Z.J.; Egedy, T.; Kondor, A.C.; Szabó, B.; Lennert, J.; Baka, D.; Kohán, B. Urban sprawl and land conversion in post-socialist cities: The case of metropolitan Budapest. Cities 2019, 92, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Patriarca, F.; Salvati, L. Tertiarization and land use change: The case of Italy. Econ. Model. 2018, 71, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneri, P. Urban spatial structure in OECD cities: Is urban population decentralising or clustering? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2017, 97, 1355–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyszy, M.; Zuzańska-Żyśko, E. Migrations of population to rural areas as suburbanization development factor (sub-urban areas) in Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolis. In Proceedings of the Geobalcanica 2018, Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia, 15–16 May 2018; Geobalcanica Society: Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Luedeke, M.K.B. The social dynamics of suburbanization: Insights from a qualitative model. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2014, 46, 980–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Antonio, M.; Hortas-Rico, M.; Li, L. The causes of urban sprawl in Spanish urban areas: A spatial approach. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2016, 11, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Carlucci, M.; Grigoriadis, E.; Chelli, F.M. Uneven dispersion or adaptive polycentrism? Urban expansion, population dynamics and employment growth in an ‘ordinary’ city. Rev. Reg. Res. 2017, 38, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y. The relationship between the urban rail transit network and the population distribution in Shanghai. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2018), Jiangnan, China, 25–27 April 2018; International Academic Exchange Center of Jiangnan University: Jiangnan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Melo, P.; Graham, D. Transport-induced agglomeration effects: Evidence for US metropolitan areas. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2018, 10, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, J.; Hauer, M.; Weaver, A.; Shannon, S. The suburbanization of food insecurity: An analysis of projected trends in the Atlanta Metropolitan Area. Prof. Geogr. 2017, 70, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence Beaulieu, M.R.; Hopperstad, K.; Dunn, R.R.; Reiskind, M.H. Simplification of vector communities during suburban succession. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgerson, M.A.; Lambert, M.R.; Freidenburg, L.K.; Skelly, D.K. Suburbanization alters small pond ecosystems: Shifts in nitrogen and food web dynamics. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 75, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, E.S.; Palmer, M.A. Restoring streams in an urbanizing world. Freshw. Biol. 2007, 52, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E. The environmental impact of suburbanization. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2000, 19, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falťan, Ľ. Socio-priestorové premeny vidieckych sídiel na Slovensku v začiatkoch 21. Storočia—Sociologická reflexia. Sociológia Slovak Sociol. Rev. 2019, 51, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.F. Historic landscape and site preservation at Gordion, Turkey: An archaeobotanist’s perspective. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2018, 28, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łupiński, W. Suburbanisation in Poland. Geogr. Inf. 2014, 18, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, G.; Hadjikakou, M.; Wiedmann, T.; Shi, L. Global warming impact of suburbanization: The case of Sydney. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Kammen, D.M. Spatial distribution of U.S. household carbon footprints reveals suburbanization undermines greenhouse gas benefits of urban population density. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyszy, M. Changes in land usage of rural areas in suburban area of Katowice Conurbation. In Proceedings of the Geobalcanica 2018, Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia, 15–16 May 2018; Geobalcanica Society: Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendall, R. Do land-use controls cause sprawl? Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1999, 26, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timár, J.; Váradi, M.M. The uneven development of suburbanization during transition in Hungary. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2001, 8, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vazquez, C. The suburbanization of the American Sunbelt after the oil crisis. Growth as an ideology and the environmental debate. Eure Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2019, 45, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveda, M. Living in the suburbia: The case study of Stupava (the hinterland of Bratislava, Slovakia). Sociológia 2016, 48, 139–171. [Google Scholar]

- Azary-Viesel, S.; Hananel, R. Internal migration and spatial dispersal; changes in Israel’s internal migration patterns in the new millennium. Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X. Innovation in suburban development zones: Evidence from Nanjing, China. Growth Chang. 2018, 50, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukavec, M.; Kolařík, P. Residential property disparities in city districts in Prague, Czech Republic. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 27, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S. Inner-city suburbanization—No contradiction in terms. Middle-class family enclaves are spreading in the cities. Raumforsch. Und Raumordn. 2018, 76, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gay, A. Towards a complex spatial pattern of residential mobility: The case of the metropolitan region of Barcelona. Pap. Rev. Sociol. 2017, 102, 793–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does smart city policy lead to sustainability of cities? Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repaská, G.; Vilinová, K.; Šolcová, L. Trends in development of residential areas in suburban zone of the city of Nitra (Slovakia). Eur. Countrys. 2017, 9, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, J. Region–city–social space as key concepts of socio-economic geography. Environ. Socio Econ. Stud. 2018, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wu, F. Paving the way to growth: Transit-oriented development as a financing instrument for Shanghai’s post-suburbanization. Urban Geogr. 2019, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, S.; Li, L.; Qi, Z. Toward a sustainable urban expansion: A case study of Zhuhai, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.; Alexandru, A.; Popa, M.; Zamfiroiu, A. IoT solution for smart cities’ pollution monitoring and the security challenges. Sensors 2019, 19, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tretter, E.M. Contesting sustainability: ‘SMART growth’ and the redevelopment of Austin’s eastside. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 37, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod Kumar, T.M. (Ed.) Smart environment for smart cities. In Smart Environment for Smart Cities; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicirelli, F.; Fortino, G.; Guerrieri, A.; Spezzano, G.; Vinci, A. Metamodeling of smart environments: From design to implementation. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 33, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N. Did highways cause suburbanization? Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-López, M.; Holl, A.; Viladecans-Marsal, E. Suburbanization and highways in Spain when the Romans and the Bourbons still shape its cities. J. Urban Econ. 2015, 85, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, I.; Trujillo, V.S. Does decentralization of the population and employment lead to a reduction in commuting distances? Evidence for the case of the metropolitan area of the Mexican valley 2000–2010. J. Reg. Urban Econ. 2019, 2, 259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, I.; Galindo, A. Urban form and the ecological footprint of commuting. The case of Barcelona. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patella, S.M.; Sportiello, S.; Petrelli, M.; Carrese, S. Workplace relocation from suburb to city center: A case study of Rome, Italy. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J.K.; Franco, S.F. Employer-paid parking, mode choice, and suburbanization. J. Urban Econ. 2018, 104, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanska, A.; Senetra, A. Forests as the key component of green belts surrounding urban areas. Balt. For. 2019, 25, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Budnicka-Kosior, J.; Janeczko, E.; Kwasny, L.; Woznicka, M. Protection of forests in the face of the progressive urbanization process—Jablonna commune case study. Sylwan 2019, 163, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Šťastná, M.; Vaishar, A.; Vavrouchová, H.; Mašíček, T.; Peřinková, V. Values of a suburban landscape: Case study of Podolí u Brna (Moravia), The Czech Republic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzyński, T.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Krupowicz, W.; Majewska, A.; Sajnóg, N. A method for identification of future suburbanisation areas. Geod. Vestn. 2018, 62, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, A. The history of urban growth management in South Africa: Tracking the origin and current status of urban edge policies in three metropolitan municipalities. Plan. Perspect. 2019, 34, 959–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pach, P. Spatial development of localities near large cities in Poland on the example of suburban area of Wroclaw. In Proceedings of the Political Sciences and Law, 3rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM2016, Albena, Bulgaria, 22–31 August 2016; Cairn International: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leetmaa, K.; Tammaru, T. Suburbanization in countries in transition: Destinations of suburbanizers in the Tallinn metropolitan area. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2007, 89, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S. Suburbanizing sofia: Characteristics of post-socialist peri-urban change. Urban Geogr. 2017, 28, 755–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, A.; Kull, A.; Gauk, M.; Tali, T. Land use policy shocks in the post-communist urban fringe: A case study of Estonia. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyorgyovichné Koltay, E. One settlement, five residential parks. Case study on the effects of suburbanisation in an agglomeration settlement. Tér És Társadalom 2018, 32, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, A.; Israel, E. Spatial inequality in the context of city-suburb cleavages–Enlarging the framework of well-being and social inequality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Zambon, I. The (metropolitan) city revisited: Long-term population trends and urbanization patterns in Europe, 1950–2000. Popul. Rev. 2019, 58, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladivo, P.; Roubínek, P.; Opravil, Z.; Nesvadbová, M. Suburbanization and local governance—Positive and negative forms: Olomouc case study. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 2015, 27, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smutek, J. Change of municipal finances due to suburbanization as a development challenge on the example of Poland. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 2017, 37, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltan, T.; Pluhar, P. Surban development area with implementation problems—Case study of Praha-East district. In Proceedings of the 8th Architecture in Perspective, VŠB, Technical University of Ostrava, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 13–14 October 2016; VŠB—Technical University of Ostrava, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Department of Architecture: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mantey, D.; Kępkowicz, A. Types of public spaces: The polish contribution to the discussion of suburban public space. Prof. Geogr. 2018, 70, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunko, M.; Medvedev, A. “Seasonal suburbanization’ in Moscow oblast”: Challenges of household waste management. Geogr. Pol. 2016, 89, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, R.; Zhou, Y. Dynamics of urban sprawl and sustainable development in China. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 2019, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnovic, I.; Kotval-K, Z.; Lee, J.; Ye, M.; Ledoux, T.; Varnakovida, P.; Messina, J. Urban built environments, accessibility, and travel behavior in a declining urban core: The extreme conditions of disinvestment and suburbanization in the detroit region. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36, 225–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoș, I.; Jones, R. Local aspects of change in the rural-urban fringe of a metropolitan area: A study of Bucharest, Romania. Habitat Int. 2019, 91, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaev, A.D.; Nedović-Budić, Z.; Krunić, N.; Petrić, J.; Daskalova, D. Suburbanization and sprawl in post-socialist Belgrade and Sofia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1389–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; Lu, H. Quantitative influence of land-use changes and urban expansion intensity on landscape pattern in Qingdao, China: Implications for urban sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, W.; Toetzer, T. Modeling growth and densification processes in suburban regions -simulation of landscape transition with spatial agents. Environ. Model. Softw. 2003, 18, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech Republic. Law No. 128/2000, on Municipalities (Municipalities); Collection of Laws No. 130/2000; Printing House of the Ministry of the Interior, P. O.: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000.

- Mulíček, O.; Malý, J. Moving towards more cohesive and polycentric spatial patterns? Evidence from the Czech Republic. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 98, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopáček, M.; Horáčková, L. Mladí lidé a trh práce: Případová studie regionů ve státech Visegrádské skupiny. In Proceedings of the XXI Mezinárodní Kolokvium o Regionálních Vědách, Kurdějov, Czech Republic, 13–15 June 2018; Masaryk University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šilhánková, V.; Koutný, J.; Maštálka, M.; Pondělíček, M.; Pavlas, M.; Kučerová, Z. Jak Sledovat Indikátory Udržitelného Rozvoje na Místní Úrovni? Civitas per Populi: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2010; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hendl, J.; Remr, J. Metody Výzkumu a Evaluace; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 2017; pp. 83–85, 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chytrý, V.; Kroufek, R. Possibilities of using the likert’s scale—Basic principles of application in pedagogical research and demonstration on the example of human relationship to nature. Sci. Educ. 2017, 8, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, H.N.; Boone, D.A. Analyzing likert data. J. Ext. 2012, 50, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J.; Tse, W.W.Y.; Savalei, V. Improved properties of the big five inventory and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in the expanded format relative to the likert format. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendl, J. Přehled Statistických Metod Zpracování Dat: Analýza a Metaanalýza Dat, 1st ed.; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 2012; pp. 175–243. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, P.A. Statistical Methods for Geography; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, D.A. Statistical Methods for Categorical Data Analysis; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Živný, M.; (Droužkovice, Czech Republic). Personal communication, 2018.

- Jandásek, J.; (Tisá, Czech Republic). Personal communication, 2018.

- Limberková, J.; (Lhotka nad Labem, Czech Republic). Personal communication, 2018.

- Pěnkava, L.; (Strupčice, Czech Republic). Personal communication, 2018.

- Drašner, K.; (Háj u Duchcova, Czech Republic). Personal communication, 2018.

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Comín, F.A.; Escalera-Reyes, J. A framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services. AMBIO 2014, 44, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefedova, T.G.; Pokrovskii, N.E.; Treivish, A.I. Urbanization, counterurbanization, and rural–urban communities facing growing horizontal mobility. Sociol. Res. 2016, 55, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, A.; Prelogović, V.; Pejnović, D. Suburbanizacija i kvaliteta življenja u zagrebačkom zelenom prstenu—Primjer općine Bistra. Hrvat. Geogr. Glas. 2005, 67, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.J.; Nigmatullina, L. Suburbanization and sustainability in metropolitan Moscow. Geogr. Rev. 2011, 101, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R.; Macdonald, S. Rethinking urban political ecology from the outside in: Greenbelts and boundaries in the post-suburban city. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 1516–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubeš, J. Analysis of regulation of residential suburbanisation in hinterland of post-socialist ‘one hundred thousands’ city of České Budějovice. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 2015, 27, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špačková, P.; Dvořáková, N.; Tobrmanová, M. ‘Residential satisfaction and intention to move: The case of Prague’s new suburbanites’. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2016, 98, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subindicator | Definition |

|---|---|

| Change in population | This indicator reflected the relative change in the population over the ten-year period, from 31 December 2006 to 31 December 2016, with 2006 taken as the base (100%). |

| Change of urbanised land area | The calculation of this indicator was based on the calculation of the change in the share of urbanised area in the whole area of the municipality for the period of ten years from 31 December 2006 to 31 December 2016, while paying attention to components of land which can be described as urbanised-built-up areas and courtyards, gardens and other areas [91]. |

| Intensity of housing construction | The calculation of this indicator was based on the average of ten annual values, which are the share of the total number of completed dwellings and the number of inhabitants in the municipality, from 2007 to 2016. |

| Change in the number of economic entities | The calculation of this indicator was analogous to the calculation of population change, except that the base of the calculation (100%) was 2013, so the intended, more relevant ten-year time series was not analysed, but only the three-year time series. The reason was a change in the methodology for data processing by the Czech Statistical Office in 2013, and so the data in a ten-year time series are not completely comparable. However, given the fact that this indicator is rather marginal (complementary) for the subject, a shorter time series is not an obstacle. |

| Category | Question | Question Code |

|---|---|---|

| territorial development | Is the share of built-up areas growing in their municipality? | A1 |

| Is the share of possible built-up areas growing in their municipality? | A2 | |

| How does new construction change the landscape character of your municipality? | A3 | |

| How does new construction change the architectural character of your municipality? | A4 | |

| municipal budget expenditures | Due to the influence of growth processes, do you spend more money on waste-water removal, treatment and sludge management? | A5 |

| Due to the influence of growth processes, do you spend more money on care for the appearance of the municipality and public greenery? | A6 | |

| As a result of the impact of growth processes, do you spend more money on other infrastructure issues (mainly parking areas and parking lots)? | A7 | |

| As a result of the growth processes, do you spend more money on repairing and managing local roads? | A8 | |

| Due to the influence of growth processes, do you spend more money on public lighting? | A9 | |

| Due to the influence of growth processes, do you spend more money on collecting and transporting municipal waste? | A10 | |

| Due to the influence of growth processes, do you spend more money on changing heating technologies (gasification)? | A11 |

| Relation of Quantity T and W at Value α | Degree of Significance of the Pair Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|

| T < W, when α = 0.05 | * |

| T > W, when α = 0.05 | ** |

| T > W, when α = 0.01 | *** |

| T > W ∧ (T − W > 1), when α = 0.01 | **** |

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 | A10 | A11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | - | ||||||||||

| A2 | 0.31 ** | - | |||||||||

| A3 | 0.43 *** | −0.15 * | - | ||||||||

| A4 | 0.37 *** | −0.13 * | 0.74 **** | - | |||||||

| A5 | 0.81 **** | 0.41 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.21 * | - | ||||||

| A6 | 0.43 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.51 **** | 0.52 **** | - | |||||

| A7 | 0.12 * | −0.19 * | 0.03 * | 0.05 * | 0.09 * | 0.14 * | - | ||||

| A8 | −0.14 * | 0.10 * | −0.50 **** | −0.36 *** | −0.16 * | −0.41 *** | 0.31 ** | - | |||

| A9 | 0.31 ** | 0.07 * | 0.34 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.12 * | 0.56 **** | 0.01 * | −0.17 * | - | ||

| A10 | −0.39 *** | −0.80 **** | 0.14 * | 0.33 ** | −0.49 **** | −0.30 ** | 0.06 * | 0.00 * | −0.05 * | - | |

| A11 | 0.40 *** | 0.21 * | −0.08 * | 0.07 * | 0.14 * | −0.23 * | −0.36 *** | 0.19 * | −0.04 * | −0.02 * | - |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hlaváček, P.; Kopáček, M.; Horáčková, L. Impact of Suburbanisation on Sustainable Development of Settlements in Suburban Spaces: Smart and New Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247182

Hlaváček P, Kopáček M, Horáčková L. Impact of Suburbanisation on Sustainable Development of Settlements in Suburban Spaces: Smart and New Solutions. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):7182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247182

Chicago/Turabian StyleHlaváček, Petr, Miroslav Kopáček, and Lucie Horáčková. 2019. "Impact of Suburbanisation on Sustainable Development of Settlements in Suburban Spaces: Smart and New Solutions" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 7182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247182

APA StyleHlaváček, P., Kopáček, M., & Horáčková, L. (2019). Impact of Suburbanisation on Sustainable Development of Settlements in Suburban Spaces: Smart and New Solutions. Sustainability, 11(24), 7182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247182