Abstract

Given the challenges presented by climate change and related environmental pressure, a sustainable, investment-led development model, i.e., aligning investment with social and sustainability objectives, is needed to ensure long-term prosperity and generate sustainable growth. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was released to guide nations towards green and sustainable development and address governance deficits. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched by China, a development strategy involving investment in infrastructure development, intends to enhance regional connectivity, integration, and stimulate economic growth. These two agendas share the notion of ‘sustainable development’ and are growing increasingly relevant. Although various studies have analysed the sustainability of the BRI, the implementation of SDGs and the similarities and complementarities between the two initiatives, few of them touched on the possibility of the BRI to be a green and sustainable investment-led model by aligning the SDGs. This paper, thus, aims to contribute to the ongoing debate on sustainable development and infrastructure investment by exploring the possibilities and challenges of the BRI to be a sustainable, investment-led development model. By comparing these two agendas and seeking the linkages between them, this article recognises the potential of the BRI to play such a role while there are issues and risks of BRI that hinder the achievement of infrastructure development and sustainable investment. The paper recommends that, to exert the synergies from aligning the BRI and SDGs to seize substantial development benefits, it is necessary to enhance the sustainability of BRI projects, provide effective cooperation and communication with stakeholders, and adapt BRI to the national development policies of each partner country. Joint efforts taken by both state and non-state actors are indispensable.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is increasingly becoming a mainstream concept on international policy agendas. The notion of ‘green development’, ‘inclusive and sustainable economy’, and ‘sustainable investment’, can be found in many formal and unofficial statements and policies. Sustainable development recently has become an imperative issue in the three pillars of international economic law, i.e., trade, investment, and finance [1,2]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) introduced by the United Nations aim to provide a response to new global and local changes that societies are facing. To achieve these goals and safeguard the demand and interests of the involved parties and companies, efforts taken by state and non-state actors as well as businesses are indispensable. Infrastructure is crucial for development and good infrastructure is essential for providing public services and also public access to these services. Although only SDG 9—Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure—directly calls for investment in infrastructure development, most other SDGs imply improvements in infrastructure from healthcare and education to access to energy, clean water, and sanitation [3]. This indicates the key role that infrastructure development can play in achieving SDGs. However, the infrastructure gap and its corresponding financing are huge and cannot be met by current national donors, private finance, and international aid. In this regard, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched by China seems a possible new approach or a potential model for solving the most pressing sustainable development challenges of the world. It is potentially the world’s largest infrastructure investment initiative and would provide a platform for delivery of investments and finance to meet infrastructure needs.

SDGs and BRI share consensus or notions in many respects, e.g., sustainable investment, infrastructure development, and cooperative mechanism; they are also mutually supportive of development agendas in certain areas. Although the BRI is not explicitly a sustainable development initiative, it embodies many of the same or similar principles that are necessary for the implementation of SDGs. However, such an initiative, which focuses on infrastructure investment may pose new environmental risks and/or governance challenges if it is not managed properly and if it does not require involved parties to take responsibilities with explicit policy guidelines, sound governance framework, and internationally recognised standards, particularly in relation to environmental protection. Moreover, the sustainability of BRI projects has been criticised or fallen under suspicion owing to the concern regarding China’s development model, i.e., a so-called ‘infrastructure-driven and debt-oriented’ model. Thus, a green and sustainable BRI would be a priority for global significance. Nevertheless, the potential of the BRI to be a sustainable investment-led development model cannot be ignored. It is important to see how the BRI can align China’s development model with social and ecological imperatives and how SDGs can be effectively integrated into the BRI.

This paper aims to explore the possibility and challenge of the BRI to be a green and sustainable investment-led model via integrating SDGs. It firstly discusses the relationship among sustainable development, infrastructure investment, and BRI and assesses the synergies between the BRI and SDGs. The impact of integrating SDGs into BRI is analysed. Secondly, it discusses the challenges of the BRI as a sustainable model, particularly the difficulties in integrating SDGs, the sustainability of BRI projects, e.g., environmental risks and finance problems, among others. It deals with the actions adopted by China at both national and international level to integrate SDGs into the BRI or promote green and sustainable BRI. Focus is put on infrastructure investment related perspectives. The last section analyses and suggests the policy and regulatory safeguards that can be used and/or are in place to support the BRI as a model for green development and sustainable investment. The efforts that state and non-state actors can take to promote a green and sustainable BRI are discussed.

2. Synergies between the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

To see the similarities and complementarities between the BRI and SDGs and argue the positive effect of aligning the BRI and SDGs, this paper employs the notion and theory of ‘synergy’ as the starting point. The phenomenon of synergies has been analysed in many different disciplines from both natural and social science. ‘Synergy’, in its broad sense, refers to ‘co-operative’ or combined effects or cooperative interactions. ‘Synergy’ concerns the structural and functional relationships of various kinds [4]. So far, an integrative or comprehensive definition of synergy does not exist.

Synergy is usually thought to originate from the Greek word ‘synergos’, which means working together. It may require ‘a platform for participation through the development of dialogues’ [5]. Some argue that synergy refers to a phenomenon that working as one system will generate greater value than working as separate entities [6]. Synergy can provide benefits and efficiencies. The benefits of synergy shared by various actors in economic activities are through cooperative action, interaction, and interdependence [7]. These benefits generated by synergy can provide mutual support and common prosperity of the various actors involved [8]. The theory of synergy requires that separate entities shall align to ensure further effective development in not only the field they exist in but also adjacent fields [9]. The effects of synergy are measurable via the consideration of different macro and micro results or performance. From an economic perspective, the effects can be measured via higher yields, reduced cost, as well as increased size and efficiency; from a systemic perspective, it can be evaluated via enhanced stress tolerance, the combining of functional complementarities to achieve new properties, etc. [4].

This paper argues that, by aligning SDGs and the BRI, the potential of the BRI to be a sustainable investment-led model can be realised theoretically. The synergy between SDGs and the BRI not only helps the two initiatives achieve their goals or aims in their own field but also works on shared objectives and adjacent areas.

2.1. The Linkage between Sustainable Development and Infrastructure

Although globalisation has continued to deepen, reaching its peak during the recent decade, human rights, social justice, and the environment face enormous challenges on a global scale in the context of a globalisation process that prioritises economic development and efficiency. Growth strategies that fail to tackle poverty and/or climate change will prove to be unstainable and vice versa [10]. Thus, sustainable development is increasingly becoming a mainstream concept on international policy agendas and is highly recommended in terms of policy making or rule-making, especially in the field of international trade and investment law [11,12,13]. The agendas of promoting sustainable development and eradicating poverty and that of climate change are deeply intertwined.

To arrest the growing carbon footprint of the global economy and its impact on the climate system, all UN Member States adopted the “Transforming out World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (the 2030 Agenda) in September 2015. As a document to guide global sustainable development, the 2030 Agenda encompasses 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in three dimensions (namely economic development through good governance, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability) and 169 targets to complete what the Millennium Development Goals did not achieve. It offers a comprehensive international policy framework for sustainable development through an inclusive and cooperative approach.

A common denominator to the success of these goals is infrastructure development. Infrastructure is an essential component of growth, development, poverty reduction, and environmental sustainability [14]. The infrastructure provides supports and services for every society in various forms, e.g., transport, telecommunications, water management, and energy. It is argued that infrastructure is core to the success of the SDGs and the prevalence of infrastructures is implicitly and explicitly expressed and required in SDGs [15]. SDG 9 is the most direct call for increased investment in sustainable infrastructure while infrastructure development can also play an important role in many other SDGs. It, however, is wise to understand that infrastructure can also create negative social and environmental impacts during the construction, operation, and upgrading of infrastructure [16]. ‘Bad’ infrastructure may also increase the vulnerability of locals to natural disasters [17] and leave an unsustainable burden of debt on governments. To address the challenges of climate change and diminishing natural resources as well as achieve good development, it is necessary that infrastructure be sustainable [18]. A major expansion of investment in modern, clean, and efficient infrastructure will be essential to attaining the growth and sustainable development objectives that the world is setting for itself. Getting these investments right will be critical to whether or not the world follows a high- or low-carbon growth trajectory over the next decade. To exert the socioeconomic benefits of infrastructure, it is important to limit their environmental costs. This requires involved parties in major infrastructure development to consider matters carefully.

At present, however, the world is not investing in what is needed to bridge the infrastructure gap, and the investments that are being made are often not sustainable [19]. In the midst of a historic structural transformation, it is the developing countries (including emerging economies) rather than developed countries that have become the major drivers of global saving, investment, and growth. Even so, the world appears to be caught in a vicious cycle of low investment and low growth, and there is a persistence of infrastructure deficits despite an enormous available pool of global savings. Climate change is already having a significant impact, especially on vulnerable countries and populations. The vulnerability to climate change may also cause debt among these countries [20]. There is a need for national authorities to clearly articulate their development strategies on sustainable infrastructure.

2.2. The Brief Story of BRI and Infrastructure

China, as the largest developing country, is a world leader in infrastructure investment, and its economic development is closely linked with the world’s development. China has pursued an infrastructure-based development strategy, which has resulted in manufacturing and infrastructure construction expertise and a wide range of modern reference projects from which to draw, including roads, bridges, tunnels, and high-speed rail projects. China’s capacities and experiences can be shared with other countries, bringing support and incentives to spur economic globalisation [21]. China has pioneered its development model in recent years and is now aligning its model with social and environmental imperatives [22].

However, recent trends demonstrate a moderate increase in protectionist measures to restrict trade and investment during the post-financial crisis era, leading to even weaker global economic growth. It also affected the paradigm of the global economic and political order. Anti-globalism, nationalism, and protectionism are spreading across Western economies. The multilateral trading system is facing challenges and dilemmas. Apart from the economic and political conflicts, the world is also facing climate change and environmental challenges. This results in increased demand for global governance that can accommodate the interests of the North and South. China, domestically, is experiencing structural issues and economic development and transition. The industrial overcapacity suffered by China requires an alternative way to address it. To provide a response to these internal and external issues, and promote sustainable development, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which focuses on connectivity and cooperation between Eurasian and African countries [23,24].

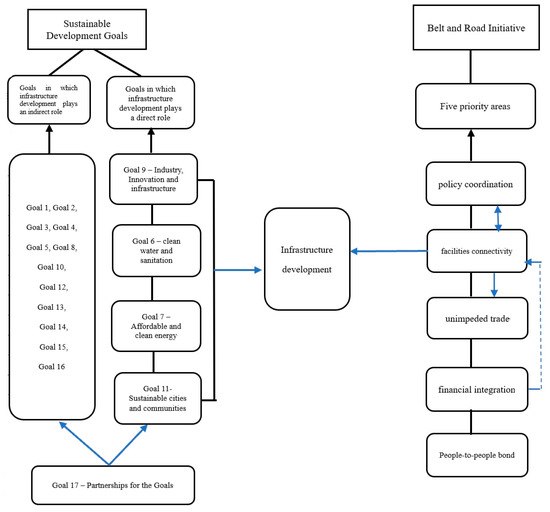

The BRI has five priority areas: policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonding. This initiative aims to address the ‘infrastructure gap’, promote mobilisation and efficient allocation of economic resources and deep integration of markets, and encourage the countries along the BRI to coordinate their economic policy and deepen regional cooperation for the purpose of creating an open, inclusive, and balanced regional social and economic cooperation framework that benefits all [25]. The aim and propriety areas of the BRI are mainly achieved via providing financing in the form of loans or investments in infrastructure, i.e., to promote infrastructure development. This suggests that the BRI and SDGs share common features via infrastructure development, as seen in Figure 1. As an infrastructure-driven and investment-led development project, the BRI may primarily affect SDG 9-Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure, particularly targets 9.1, 9.4, and 9.6, which consider building, upgrading infrastructure, and facilitating sustainable infrastructure developing through enhanced financial, technological, and technical support.

Figure 1.

The relationships among sustainable development, infrastructure investment and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The world has a large infrastructure gap that constrains future prosperity. Many multilateral development banks are trying to close this gap. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), to maintain the growth of Asia and respond to climate change, around $26 trillion infrastructure investment is needed until 2030 [26]. If the financing that is needed to meet SDGs is considered, the figure will increase. In this regard, BRI investment projects are estimated to add over $1 trillion of outward funding for infrastructure over a 10-year period beginning in 2017. This indicates that the BRI can contribute towards achieving SDG 9 directly and also several other SDGs indirectly, e.g., SDG 7-affordable and clean energy and SDG 17-partnerhips for the Goals [27]. It constitutes a natural extension of the infrastructure-driven economic development framework that has sustained the rapid economic growth of China since the adoption of the reform and opening up. The BRI reflects China’s rise as a global power as well as its industrial redeployment and increased outward investment. The BRI involves the establishment of a framework for open cooperation and new multilateral financial instruments designed to support BRI projects and reduction of poverty [28].

The geographic coverage of BRI has two main branches, i.e., the Silk Road Economic Belt (the Belt) and the 21st Maritime Silk Road (the Road). The Belt has three routes, linking China to Europe through Central Asia and Russia; connecting China with the Persian Gulf and Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and West Asia; and bringing together China and Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean. The Road has two routes: it links Coastal China with Europe through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean; it also connects Coastal China with the South Pacific through the South China Sea. At the start, the BRI involved 64 economies (besides China) (see Table 1), but, so far, more than 100 countries have expressed their support or willingness to participate in the building of the BRI projects in some form, particularly via bilateral cooperation mechanisms, e.g., Memorandum of Understandings, roadmaps, or implementation plans. At present, no time frame for the BRI has yet been specified. Some projects have already commenced construction while others are in the pipeline. So far, a total 124 countries and 29 international organisations have signed BRI cooperation documents with China [29].

Table 1.

65 countries involved in the BRI. Note: For 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, involved countries are Ethiopia, Kenya, Morocco, New Zealand, Panama, Korea, South Africa. Source: China International Trade Institute. The countries are grouped based on World Bank’s classification by region.

The projects under the BRI are mainly related to infrastructure development, some of which are financed by BRI funding mechanisms while others are officially branded under the BRI. The majority of these projects are in relation to transport and energy [30] but also cover industrial parks, Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and urban development. For example, several key BRI projects in transport may include the Hungary-Serbia Railway Project, the Thai-Chinese railway and the China-Laos railway. The China-Europe freight train service was launched in 2011 as a significant part of the BRI. Kenya opened a railway project linking Rift Valley towns and Nairobi. As part of the Maritime Silk Road under the BRI, Greece’s Piraeus port and Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port project are flagship BRI projects. Notable BRI projects in other fields or forms may include the China-Myanmar oil and gas pipeline, Sihanoukville SEZ (Cambodia), and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. These selected key projects demonstrate the broad geographic coverage of the BRI.

Different stakeholders have become involved in the BRI or specific BRI projects. Apart from the host country’s government, local communities, civil society organisations, international organisations, businesses, as well as national and multilateral financial institutions are important players, as seen in Table 2. This has made cooperation for BRI projects diversified but also brings about complex issues considering the different interests of these stakeholders. However, at present, much attention has been paid to issues relevant to government bodies rather than the concerns of businesses, local communities, and civil society organisations, resulting in suspicion or even public criticism of the BRI. This requires China, in the next step, to conduct a better analysis of the interests of various stakeholders and itself, particularly with regard to sustainable development.

Table 2.

Different stakeholders involved in the BRI. Note: Examples or stakeholders selected by this paper are incomplete. It serves only as supporting materials for understanding.

2.3. The Main Notion and Philosophy that the BRI and SDGs Share

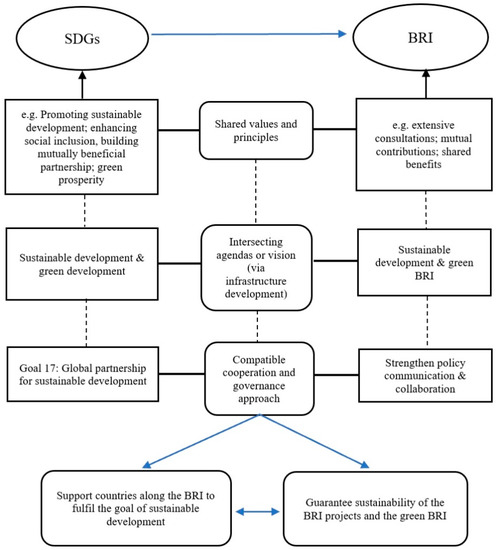

As an open, inclusive, regional cooperation mechanism, the BRI is highly aligned with the 2030 Agenda [31], i.e., these two initiatives have shared principles, intersecting agendas, compatible cooperation, and governance approaches (see Figure 2). The BRI has identified key areas of cooperation, namely, policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people exchange [21]. In essence, this initiative is to promote sustainable development along the BRI as well as in China, mainly via infrastructure development.

Figure 2.

Synergies between BRI and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Firstly, the principles and values of the BRI and SDGs are very similar. The 2030 Agenda (or the SDGs) consists of a number of concepts, e.g., promoting sustainable, widespread and green prosperity, enhancing social inclusion, building mutually beneficial partnerships, and the protection of the material and ecological basis for human development. The BRI emphasises the principles of extensive consultations, mutual contributions, and shared benefits. The BRI embeds China’s global development view, i.e., ‘collaborative development’ and China’s approach to reform, i.e., ‘adaptive governance’ [32].

Under the notion of the BRI, it is encouraged that countries work in concert and move towards the objectives of mutual benefit and common security. Specifically, for example, they need to ‘improve the region’s infrastructure, lift their connectivity to a higher level; further enhance trade and investment facilitation, establish a network of free trade areas that meet high standards, maintain closer economic ties, and deepen political trust; enhance cultural exchanges; encourage different civilisations to learn from each other and flourish together; and promote mutual understanding, peace and friendship among people of all countries [21]’.

Secondly, the BRI has a similar vision as the 2030 Agenda. Sustainable development and green development are covered by the notion of both agendas [33]. Both are committed to promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth and social development; the BRI’s vision to realise diversified, independent, balanced, and sustainable development in the countries along the BRI echoes the sustainable development goals set out in the 2030 Agenda. Infrastructure development, which is included in the SDGs, is the core mission that the BRI intends to achieve. Hence, there are plenty of opportunities that the BRI can have to contribute to problems that SDGs are intending to solve through the special importance of infrastructure connectivity [34].

In terms of green development, environmental relevant factors are not only included in the specific SDGs, e.g., SDG6-clean water and sanitation, SDG 13-climate action, SDG14-life below water and SDG 15-life on land, but are also being incorporated into the BRI. The notion of greening the BRI was shared and emphasised at the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. Building a green BRI means protecting the environment as a priority. The Belt and Road Green Investment Principles (GIP) and the BRI International Green Development Coalition (BRIGC) were launched during the forum. The BRIGC, which involves 134 partners, is a voluntary international network to ensure the environmental sustainability of the BRI and sustainable development of all countries concerned in support of SDGs [35]. On the basis of existing factors in relation to the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and responsible investment initiatives, the GIP aims to ensure that the new investment projects in Belt and Road countries incorporate sustainable development and low-carbon practices [36].

Thirdly, the 2030 Agenda advocates increased international cooperation, especially through the implementing means listed in SDG 17 to revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development. Meanwhile, the BRI seeks to strengthen policy communication, build multi-layered intergovernmental macro-policy communication and interaction mechanisms, and establish a platform for communication and exchange for consensus and mutual benefits. This can be also found in the fundamental principles for the BRI advocated by China, i.e., the principle of achieving share growth through discussion and collaboration. Both the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the advancement of the BRI require the establishment of communication and exchange mechanisms as well as cooperation platforms. For example, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road port cooperation mechanism established between China and 13 other countries intends to serve the demand for better infrastructure connectivity while the China-Latin America development financial cooperation mechanism established by China Development Bank aims to promote financial integration [37]. The purpose of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in the view of China is the building of a more open and efficient international cooperation platform. Furthermore, the similarities between these two implementation platforms will enhance opportunities for further cooperation.

The BRI and SDGs can interact with each other to fulfil the goal of sustainable development, especially with the support of countries along the BRI [38,39]. On one hand, the BRI can be regarded as an important and historical opportunity for promoting and implementing SDGs. On the other, the BRI could maximise its outcomes if it were to be aligned with the SDGs and become a sustainable, investment-led model. This requires the BRI to aim to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs of participating countries in the areas of basic infrastructure, regional development, connectivity, and industrialisation—as per its stated goals.

Moreover, integrating SDGs into the BRI would extend and upgrade the initiative to explicitly serve sustainable transformation of the countries along the Belt and Road, ensuring that the BRI policy domains create leverage towards poverty reduction, environmental sustainability, and inclusive social development, all of which are deemed key elements for the BRI’s success in the long term [34]. In doing so, the BRI could serve as an accelerator, an effective vehicle to achieve the SDGs. At the same time, in lining up with the SDGs, the BRI would be in the proper position to advance the common good of participating nations in every key area of development. But this paper mainly focuses on and discusses issues in relation to infrastructure investment (including financing for those projects) for achieving sustainable development. By recognising the important role that the BRI can play, the UN expressed its willingness to support the alignment of the BRI with SDGs for maximum sustainable development dividends [40].

In terms of infrastructure investment, infrastructure connectivity is a priority and a key object of the BRI [41], while financial integration provides a fundamental role to guarantee the long-term operation and development of infrastructure projects. SDG 8 also emphasises the importance of infrastructure. Financing is not only important for achieving the SDGs but also important for supporting and guaranteeing infrastructure projects along the BRI. Efforts are required to be taken by the international community or countries along the BRI to discuss the amounts of concessional financing needed to meet the SDGs and consider how to mobilise the financing and how best to deploy it to support the economic, social and environmental goals embodied in the SDGs. Moreover, China, as the promoter of the BRI, should also consider its capacity to provide sustainable funding resources for BRI projects (e.g., collaborate with other countries’ investment funds, financial institutions, or multilateral investment funds) and reduce relevant risks (e.g., sovereign debt risk).

3. Sustainability and Challenges of the BRI

The launch and advance of the BRI has been accompanied by voices of support as well as concerns and doubts. The opportunities that the BRI can provide and challenges/risks it may create have been widely discussed or questioned, as seen in Table 3. This paper has, in previous sections, analysed the benefits of the BRI; in this section, it discusses the challenges which the BRI has faced with regard to integrating SDGs into the BRI and the possibility of the BRI being a green and sustainable model.

Table 3.

Opportunities and Challenges of the BRI.

3.1. Challenges in Integrating SDGs into the BRI

Although the BRI and SDGs have interlinked principles, shared visions, and compatible cooperation approaches, differences exist in terms of coverage, background, objectives, and implementations. It is largely attributable to the 2030 Agenda is a global-level initiative while the BRI is a regional-level initiative (despite the currently more than 100 economies and institutions involved). These differences result in issues and challenges in achieving SDGs via promoting the BRI. Among these, geopolitical risks, economic risks, as well as social, environmental, and legal risks are the main challenges of implementing the BRI [42,54,55]. In terms of integrating SDGs, several key challenges remain not only for China but also for other countries along the BRI. China and other countries face a major challenge in their attempt to feasibly integrate the initiative into a sustainable development path. As the implementation of a green and sustainable Belt and Road, those involved (both state or non-state actors) will need to thoroughly examine the core strategies and principles behind the initiative, as well as ensure that local communities at both the provincial and regional levels are fully engaged.

In terms of integrating SDGs, countries along the BRI and China may have different considerations or priorities. This suggests that effective plans are required in implementing the BRI to maximise the synergy between the BRI and national policy of participating countries, particularly policies or strategies to fulfil SDGs. The premise to realise and achieve policy communication is to effectively link national development strategies of participating countries, but, in reality, from the operational and implementing perspective, reasonably linking development strategies of participating countries is not enough.

The current reality is that the majority of the countries along the BRI are developing countries. Moreover, the economic dimension, state system, regime polity, culture, and language, even the stage of development, may vary from country to country. Under the framework of the BRI, it is difficult to achieve a universal standard in implementation, thus domestic policies need to meet the national development planning of participating countries to make the BRI easily accepted by the government and people of participating countries [56]. In addition, the communication with local-level policy in the host countries is relatively weak. Under the BRI, China promotes investment in infrastructure construction in host countries, but the problem of land expropriation tends to become the most pressing problem between Chinese enterprise and host countries [57]. Infrastructure projects, roads, railways, airports, and hydropower projects in developing countries are usually located in remote areas. The land expropriation problems involved in construction project need to be communicated adequately with the local government and people. This needs public communication and coordination through local government, departments, and the public to resolve contradictions, and to ensure the broad public basis of the implementation of the project. However, the importance of these works is often easily ignored. When projects are hastily begun after signing on, caused by a lack of coordination with the local government and the public communities, coupled with poor language and culture differences, the implementation of the project will be slowed and/or the project cannot be built. Although the expansion of infrastructure projects may have severe impacts on ecosystems, it is important to note that not all types of infrastructure are bad for the environment. Well-deigned and new infrastructure can generate both economic and social benefits [17].

The environmental challenges can be turned into opportunities for environmental stewardship if China and other countries develop the BRI within the framework of strategic environmental and social assessment in line with high environmental standards [58]. The contribution of the BRI to the world is not only to provide public good for regional and even global economic development, but also provide a global economic governance approach, i.e., a more flexible approach under which other countries can voluntarily choose their own approach to participate. This highlights the prevalence of considering different interests and national development policies.

3.2. Issues of BRI Projects

The other main challenge originates from the sustainability of Belt and Road projects, especially green investment and the long-term development of the projects. Firstly, the BRI covers an area that has the world’s most prominent ecological problems. Developing countries along the Belt and Road are facing serious environmental security challenges, and their ability to handle these challenges is very weak. Moreover, some countries along the BRI have a poor record of environmental governance, which means that projects may be undertaken without external pressure to comply with social and environmental standards [54]. China is facing a severe test as to whether it can achieve resource saving and environmental friendly infrastructure and international cooperation to avoid countries along the BRI from replicating the high pollution, high emissions, and high-energy consumption development model.

Secondly, SDG 9 emphasises the aim to ‘build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation’, and ‘develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all.’ It also requires all UN member states to ‘upgrade infrastructure and retrofit industries to make them sustainable, with increased resource-use efficiency and greater adoption of clean and environmentally sound technologies and industrial processes, with all countries taking action in accordance with their respective capabilities’ by 2030. Infrastructure construction is the priority development goal of the BRI and plays a fundamental role in green and sustainable development of the region. However, due to the long cycle of use and high degree of infrastructure utilisation, the degree of energy conservation and environmental protection in the future will affect the regional resources and environmental condition for a long time. The construction of infrastructure project may consume a lot of resources and energy and may also produce, among others, waste water and solid waste, thereby resulting in new environmental problems.

Despite the relative backwardness of their economic development, developing countries attach great importance to protection of the environment and natural resources. Due to the relative open and developed social media and news in these countries, the national environmental protection consciousness of many countries is very strong, which results from promoting the notion of environmental protection by the local media, civil societies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Local government, think tanks, and the public of these countries are concerned about the potential environmental impact of China’s infrastructure projects. They argue that the advantage of Chinese projects in the host country is given priority to projects with a low price; thus, the quality of projects is controversial. Given rising Chinese investment in hydropower construction projects and the potential adverse effects on the environment, it was argued that countries along the BRI should be more cautious about China’s investment [49]. The potential water and electricity market in the countries along the Belt and Road is enormous. The rapid development of China’s hydropower construction projects overseas has sparked the attention of governments, the public, and NGOs to ecological environmental protection. The adverse effects on the biodiversity and ecological environment caused by land occupation, closure of river construction, and quarrying soil have become the topic of Western media and environmentalists, which tend to attack Chinese overseas investment.

Chinese construction projects in Belt and Road countries has focused on the railways, ports, roads, and dams. The 2017 ‘Global Ecological Environment Sensing Report’ noted that, since 82% of the area earmarked for the BRI was covered with forests, grasslands and desert, these geographical conditions make it difficult to build connecting roads [59]. It also documented pockets of water reserves along the BRI, and warned that some of them had been overused by agriculture, thus raising concerns about water shortages.

With the deepening of the BRI, opportunities for Chinese overseas investment will continue to grow, accompanied by increased environmental risks [50]. If Chinese investors ignore the environmental protection, it will not only cause issues between Chinese enterprises and the local people, but also hinder the implementation of the BRI. If investors intend to undertake overseas economic activity, the first and most important thing to do is to protect the environment while running businesses. This relates to the notion of corporate social responsibility and sustainable responsible investment. Following this course will help the local people perceive the value of the BRI. Adherence to the green development, therefore, is the precondition for sustainability of the BRI.

Secondly, the concern of sustainability of the BRI lies in the issue of financing. Demands for infrastructure in developing countries and for funding are huge, which cannot be satisfied only by the government’s financial resources and management. After the outbreak of the 2008 financial crisis, the development aid provided by developed countries declined [60]. Relying only on official development aid provided by developed countries cannot meet the demand; thus, it needs the international community to broaden sources, to attract the broad participation of social capital, and to provide the service efficiency of funds.

In terms of BRI projects, China tries to provide funding sources for these projects, which resulted in the establishment of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund. Chinese state-owned banks are participating in funding the BRI projects; however, those Chinese banks arguably do not have a good record of efficient assets allocation. Although financial support is flowing under the BRI, one concern is the management of environmental and social risks by Chinese financial institutions, particularly in countries with weak environmental governance [61]. In addition, the BRI has been criticised for raising debt risks in weak economies or resulting in a debt trap. It has been reported that Pakistan is facing a debt crisis in part due to the BRI project with China [62], which results in its turning to the IMF for bailout [63]. On 3 July 2019, the IMF approved a $6 billion bailout package for Pakistan and according to the IMF’s analysis, ‘more than 25 percent of Pakistan’s outstanding public debt’ is ‘bilateral or commercial debt to China’ [64]. A series of controversies that have flared up in countries as far apart Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, and Montenegro are all related to the difficulty in repaying debts for the BRI-related projects [65]. Concern regarding a debt trap or debt sustainability, either because of the perceived inability of countries to handle the so-called outsized debts to China, also have been raised by Sri Lanka and Nepal recently [66]. However, in this regard, it is important to see whether there are some misunderstandings of these BRI projects. This requires increased transparency of these projects and also enhanced communication with involved countries.

On the other hand, Chinese banks and financial institutions have provided more than $440 billion in loans for BRI infrastructure projects [67]. According to a recent study, among 68 countries identified as potential BRI borrowers, eight countries are at particular risk of debt distress based on an identified pipeline of project lending associated with the BRI [68]. The debt problem of the BRI projects runs the risk of derailing the BRI and even jeopardising China’s economy. It raises the question as to whether China will be financially sustainable to achieve its sustainable development or environmental pledges/commitments. The Chinese government has realised the debt risk and importance of debt management. At the second BRI forum, the Ministry of Finance released a debt-sustainability analysis framework, i.e., a ‘nonmandatory’ policy tool based on international standards provided by the IMF and World Bank, for participating economies to rate debt risk before lending [67].

Another issue lies in the degree of involvement of public and private bodies or resources. The active actors in BRI projects are mainly state-owned or have a government background. Many projects were agreed between governments or criticised for having a lack of transparent procurement processes, or poor project selection [69]. As mentioned before, projects are mainly funded by Chinese state-owned banks. Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are the main participants in BRI projects and play a leading role in the implementation of the BRI. Chinese central government-run SOEs have undertaken more than three thousand projects under the BRI and contracted about half of BRI projects at more than 70 percent by project value [70,71]. Given this, the ‘principal-agent dilemma’ may occur and the motivation behind Chinese SOEs investment would be questioned. In addition, under the BRI, the private sector investments in infrastructure spending generally is far behind that of public sector. According to the ADB, it is important to attract greater private sector participation in infrastructure. This requires governments to provide an ‘enabling environment’ that include effective risk allocation and a risk transfer mechanism [72].

4. Internal and External Actions to Integrate SDGs into the BRI

4.1. Measures and Actions at National Level

To promote BRI infrastructure investment and increase the capacity and level of sustainable development of countries along the BRI, China released a series of policies in relation to the economy, finance, environment, infrastructure, and mechanisms.

At present, policies to promote sustainable development of the societies of participating countries were generally made to serve economic communication, mainly related to law, education, culture, agriculture, science, and technology in key areas. The basic requirement of BRI infrastructure development is protecting the ecological environment; therefore, China has put forward the requirement for strengthening energy, cooperation, and has pushed forward the construction of the green BRI; consequently, the ‘Vision and Actions on Energy Cooperation in Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ and ‘Guiding Opinions on Promoting Green Belt and Road Construction’ were released. The ‘Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan’ was put forward as an important measure to implement the SDGs.

Facilities connectivity is the basic guarantee to improve the level of sustainable development along the Belt and Road. According to “Co Construction of Belt and Road: Concept, Practice and Contribution of China”, to strengthen infrastructure construction, promoting cross-border and cross-regional interconnection is the priority in building the BRI. At present, the released policies mainly include two aspects, i.e., improving transport facilitation supported by the ‘Opinion on Implementing the Belt and Road Initiative and Speeding up the Promotion of International Road Transport Facilitation’ and building information networks supported by the ‘Guiding Opinions on Speeding up the Construction and Application of the Space Information Corridor along the Belt and Road’ and other relevant documents. The Chinese government is currently prioritising implementation of the principles in two documents—the 2017 Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road (jointly issued by the Ministry of Commerce, Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and National Development and Reform Commission), and the Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan. A case in point is the annual Guide for Countries and Regions on Outward Investment Cooperation. The 2018 edition of the Guide covers 172 countries and regions and, following the changes of the world political economy, updated the financial environment, investment regulations, preferential policies, and the infrastructure status and development planning especially for countries along the BRI to ensure that Chinese enterprises understand the investment environment of the host country timely [73].

Actions have been taken to oversee and restrict Chinese overseas investment for the purpose of ensuring that overseas deals are rational and legal by providing a 36-point code of conduct for private firms, known as the ‘Measures for the Administration of Overseas Investment of Enterprises’ along with other relevant rules. The Chinese government supervises these outbound investment via report requirements; approval for investments involving sensitive industries or countries while investment in BRI projects is strongly encouraged. It indicates that investment activities that are in line with national policy or economic demand can receive better regulatory support. Although the focus of these measures is put on guiding investments in sound assets, ensuring sustainable outbound investment is the final gain.

However, many of these actions are encouraged via soft law regulation or guidelines rather than mandatory regulation; thus, the effect of these actions may be questioned. Soft law is usually regarded as nonbinding standards and principles of conduct without enforcement mechanisms [74]. These internal efforts are mainly designed for guaranteeing the overall profile of the BRI and the conduct of Chinese investors overseas, while the Chinese government has not provided a code of conduct or specific guidelines for its SOEs as the key players in BRI projects. Suggestions have been made to regulate the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) disclosure in China; however, in corporate law, there is no clear concept of what CSR Chinese enterprises should bear and what relevant information they should disclose [75]. This requires that certain key responsibilities, especially those in relation to environmental protection, should be incorporated into specific laws, e.g., environmental law. Increased standards in the domestic market can help Chinese investors build its image overseas as responsible investors. But changing all soft law regulation into hard law is not necessary, while ‘hardened’ soft law regulation can guarantee that enterprises fulfil their social responsibilities [76].

Nevertheless, it should be admitted that these action plans or guidelines set minimum standards and specific goals that the BRI intends to achieve and comply with. It not only considers the issues domestically but also the role of enterprises, and the cooperation with different countries and institutions. The effectiveness of these action plans relies on a sound comprehensive coordination mechanism at multiple-levels.

4.2. Measures and Actions at the International Level

The SDGs were invoked as the guiding objective for the environmental dimension of the BRI. China emphasises that environmental protection in the BRI is part of the efforts to achieve sustainable development, which reflects its consistent stance of linking the environment with development. China has been actively engaging international organisations and in all regards has displayed its reliance on experts, in line with its partnership with the World Bank. International organisations and regional inter-government cooperative associations play a critical role in China’s external effort to integrate SDGs into the BRI and promote green and sustainable investment along the BRI.

Firstly, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), since its adoption in 2015, supports countries’ efforts to achieve the SDGs. It has been supporting China’s development processes for over three decades. Early on, the UNDP positioned itself to have a state-level and strategic partnership on the BRI. The UNDP was the first international organisation to sign a Memorandum of Understanding in September 2016, and then a concrete Action Plan in May 2017 as a framework for cooperation. In April 2018, the first high-level meeting of the UNDP-China Joint Working Group on the BRI was held with an updated list of projects that will be recognised as deliverables of the UNDP-Government of China cooperation and presented officially at the Belt and Road Forum in 2019. The UNDP has anchored the strategic partnership with China with the leading group on the BRI, including the National Development Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), China Development Bank (CDB), and China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA). UNDP China also engages with other key government entities, financial institutions, the private sector, think tanks, as well as media and social organisations. Building global networks and partnerships is deeply embedded in the UNDP’s BRI engagement.

In 2012, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection signed a framework agreement on strategic cooperation; since then, China has pledged $2 million annually to the China Trust Fund to build the capacity of developing countries in addressing environmental challenges [77]. In addition to sponsoring UNEP’s projects, China has capitalised on UNEP’s expertise to analyse and advise on China’s environment efforts. In 2013, UNEP and the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection jointly produced a report “China’s Green Long March,” assessing China’s progress towards a green economy [78]. It was argued that, by adopting green financing, the BRI can make a significant impact on sustainable infrastructure construction [79].

Secondly, China took on the Presidency of the G20 in 2016. The outcome of the Summit generated consensus for the G20’s long-term vision and committed leaders to a blueprint for innovative growth, pushing for openness in trade and investment while promoting a fairer and more equitable global governance system focused on inclusive development. That has led to the adoption of the G20 Action Plan for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [80], thereby supporting for the first time a strong alignment between the G20 and the global development agenda.

Thirdly, China has actively engaged in dialogues with the BRICS cooperation platform, especially in promoting the establishment of the BRICS Development Bank and the Emergency Reserve Fund, which features China-led initiatives reshaping international development financing. At the BRICS Goa Summit in 2016, President Xi Jinping outlined five priorities for BRICS cooperation, which includes constructing a shared vision for global development, keeping a central focus on development issues, and pushing the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In 2017, BRICS adopted the ‘BRICS Leaders’ Xiamen Declaration’ reaffirming their commitment to fully implementing the SDGs [81]. A study shows that BRICS countries have not been adopting SDGs in their entirety, among which China demonstrates more interest in SDGs in comparison with India, Russia, Brazil, and South Africa [82].

Although various efforts and actions have been made by China unilaterally or collaboratively, the sustainability of the BRI and the promising role of the BRI in achieving SDGs are in doubt, especially from the perspective of Western countries and even several countries along the Belt and Road. It cannot denied that main critics of the BRI originated from geographic and political reasons rather than purely economic reasons. But much of the scepticism, in the view of this paper, stems from the following reasons/concerns: (a) the lack of a clear regulatory framework/regime for the operation of the BRI; (b) the divergence of the economic development model; (c) the concern of the “China plus” bilateral cooperative model (Where is the opportunity for more countries to get involved and to promote their own development planning?); (d) insufficient incentives and regulatory guarantees for encouraging the involvement of private capitals; (e) the lack of necessary environmental impact assessments and sufficient funding recourses; and (f) the behaviours and conduct of Chinese investors. These concerns consist of considerations from micro and macro aspects, i.e., the overall picture and framework of the BRI and China’s policy, and the small picture of the Chinese participants in the BRI.

5. Way Forward

5.1. General Considerations

China is trying to take actions to promote a green and sustainable BRI in line with SDGs. However, further actions are needed by the Chinese government and investors at both the national and international level. The participation of other countries and stakeholders is necessary and important to guarantee the sustainability of the BRI. It is not only limited to policy-level coordination and cooperation but also include cooperation in other relevant areas, e.g., drafting codes of conduct for investors or imposing investors’ obligations as well as promoting cooperation between/among financing institutions or institutional investors of countries along the BRI.

Integrating SDGs into the implementation of the BRI can take care of each country’s different interests and concerns. It requires aligning SDGs and the BRI firstly at the policy level, and integrating relevant projects into the national and local government development agendas. Insisting on promoting the BRI under the framework of SDGs will avoid developing countries from destroying the ecological environment in exchange for economic growth, thus correctly handling the relationship between economic development and ecological environment protection. Only in this way will the BRI become practical and feasible in countries along the BRI and garner the support from local people in those countries, thereby promoting economic growth, social inclusion, and realisation of the construction of a community of shared future for mankind.

At present, numerous participating countries have established their own development strategy in terms of planning and macro policies, the purpose of which is to promote the sustainable development of the country or region. In the process of promoting the BRI, it is important and necessary to strengthen the coordination of these national policies of countries along the BRI. It also requires to be positively in line with the SDGs. The Chinese government could set the involved areas and targets as the key areas of cooperation and direction to promote the BRI. On the basis of the SDGs, it is necessary to monitor and analyse achievements, progress, and deficiencies, e.g., by releasing the BRI national sustainable development report every year.

Infrastructure is the important guarantee of sustainable development. Promoting infrastructure connectivity also requires firstly fitting and satisfying the local needs. This is the premise for advancing facilities’ connectivity. Only in accordance with local or regional governments and people’s needs and interests can infrastructure connectivity projects proceed smoothly; therefore, communication and propaganda work must be carried out before the commencement of the projects.

Moreover, to promote the coordinate development between and/or within the regions along the Belt and Road, the key approach is to guide the orderly and freely flow of capital as far as to provide a unified open, competitive, and union market system. On the basis of resources endowment, to develop industries with comparative advantages, it is important to promote bilateral and multilateral trade. The second is to create a good institutional environment for the industry transfer and absorption of foreign direct investment (FDI). On the premise of green development, it is critical to encourage FDI and the industrialisation process in less developed areas.

To guarantee the operation and sustainability of infrastructure investment projects, the role of financing can hardly be ignored [83]. It also needs efforts to be made in the private sectors [83]. Green finance is the important source of funds for BRI projects. In the past few years, green finance has rapidly expanded in global scope, thanks to its growth in China. The challenge of expanding green finance in China is due to the highly fragmented policy framework, i.e., according to different kinds of finance, departments, as well as inbound and outbound investment, there are separate provisions. China needs to develop in line with international standards of sustainability criteria, and this applies to both domestic and overseas investment. A corresponding mechanism to regulate the behaviours of project participants is necessary. China’s green financial working group and the G20 green finance team have already started to formulate the corresponding standards. The People’s Bank of China and the European Investment Bank have also started to cooperate through making the definition of green finance more consistent, to strengthen green finance.

The ultimate responsibility lies in the government in terms of ensuring properly designing and planning national infrastructure projects, minimising the negative environmental and social impacts, and ensuring that the project conforms to the national sustainable development strategy. However, The government does not always have the desire to or willing to regulate all aspects. As a result, investors may have to take responsibility themselves. Investors play an important role in promoting sustainable infrastructure and green investment [84]. By encouraging investment in the field of transportation, energy, and communications, infrastructure strengthens the inter-operability of China and the world. Infrastructure will exert social and environmental influence. One expected result of the BRI is to help partner countries to achieve sustainable development, but it will depend on the nature of the investment project. The international community has not provided a generally accepted definition of sustainable investment or sustainable infrastructure, thus investors may find it difficult to identify such projects. In practice, it is not easy to determine the boundary of acceptable environmental and social impact. This may requires governmental effort to provide answers to relevant questions, e.g., how can a standard and trusted definition be built? How can the agreed standard be implemented in BRI projects? What kinds of methods can promote green investment and sustainable infrastructure that are the most effective or widely accepted?

Each country’s efforts to engage in the BRI will be most efficient when they are oriented by their strong alignment with their national strategies of implementation of the 2030 Agenda. This is particularly important for developing countries’ effective participation in the BRI framework to support their country’s development. The BRI provides a platform and opportunity to accelerate countries’ efforts to integrate the SDGs. National level policy-making represents the basis for BRI engagement and its effective implementation. However, the cross-border character of many BRI investments and projects requires cooperation and strong coordination at the regional and international levels to govern these investments beyond national borders. The coordination and strategic alignment of BRI relevant governance dimensions should further draw on regional mechanism or special ‘Belt and Road mechanisms’ to channel the development demand of the involved parties and develop cross-border synergies in trade, investment and financing.

The BRI is trying to mobilise common interests and provide public goods in various geographical regions and embracing various fields of policy. China has been working with countries along the Belt and Road to advance and promote projects and programmes by leveraging and complementing existing bilateral and multilateral mechanisms for regional cooperation. The BRI can be a significant contributor to global governance and sustainable development if it emerges from a more multilateral engagement. In this regards, supranational or regional agreements seem necessary for incentivising the participation of involved stakeholders and guaranteeing the implementation of SDGs in BRI projects.

5.2. Specific Policy Recommendations for Policymakers

On the basis of the general considerations outlined above, this paper intends to put forward the following specific policy recommendations for further integrating SDGs in the BRI and promoting the potential of the BRI to be the green and sustainable investment-led model:

In general, recognise the development benefits that the synergies of aligning SDGs and BRI can provide. To make it work, it is necessary to integrate SDGs that directly call for infrastructure development, e.g., SDG 9, into the design and implementation of BRI projects, and integrate SDGs that indirectly require infrastructure development, e.g., SDG 6, in the policy-making and cooperation process. The direct synergy between SDG 17 and the BRI cooperative approach should be acknowledged, i.e., international and/or regional cooperation and coordination are the cornerstone of realizing the potential of the BRI.

Work on adapting BRI implementation and policies to the national development agendas or national needs in each country along the Belt and Road or in a group of countries sharing a similar regulatory and cultural environment. This requires consideration of how specific BRI projects can accommodate the propriety of achieving SDGs in each host country and also consider the interests of local communities or other stakeholders. To support this, it might be helpful if involved countries can provide a kind of annual or quarterly report with regard to their implemented measures for the achievement of sustainable development.

Maintain and provide key platforms or mechanisms for policy-level cooperation among state and non-state actors, i.e., public and private sectors. This requires the BRI Forum for International Cooperation to act as a basic platform while other regional and international organisations, private associations should provide corresponding assistance or forums for discussion about achieving SDGs. In particular, for the financing of BRI projects, it is necessary to advance cooperation among national and multilateral financing institutions, institutional investors, and special funds.

Enhance communication with local communities and spread the message that the BRI has the potential to be a sustainable, investment-led development model. This requires government authorities and investors to pay sufficient attention to the communication with affected local communities and civil society organisations, and provide more opportunities for dialogue.

Identify key areas for public and private cooperation in implementing BRI projects. This firstly requires both the Chinese government and host country’s governments to provide a friendly and sound business environment with necessary trade and investment protection and promotion regulations, rules, and policies. The support of domestic courts (in particular special international commercial courts), and arbitral and mediation institutions is necessary for dispute resolution. Secondly, importance should be given to principles of green finance or green investment (e.g., the GIP) and the social and environmental responsibility for Chinese companies operating abroad and other multilateral companies. ESG factors should also be encouraged to be incorporated into decision-making, in particular, in BRI projects. For those released principles or codes of conduct, supplementary guidelines or instructions can be provided by the government or other associations for better understanding of the implementation. Other third-party service providers or professional firms can also play an important role in drafting relevant standards. Last but not least, China and its BRI partner countries can provide or draft guidelines of sustainable infrastructure and investment, based on SDGs and internationally recognised standards, for investors when conducting BRIs.

These joint efforts by state and non-state actors would contribute to realising the potential of the BRI to be a sustainable, investment-led development model and achieve the SDGs to a certain extent. The BRI already demonstrates that it can provide regional public goods, infrastructure connectivity, as well as trade and investment opportunities while issues and challenges in implementation limit its ability to be well-functioning. However, the synergies of aligning SDGs and BRI provide a chance to create greater development dividends and for the effectiveness of the BRI. By participating in building a green and sustainable BRI, partner countries would acknowledge their own optimal development pathway and adapt their current model to a more sustainable way. Integrating SDGs in the BRI would help China demonstrate its role to the global world in promoting sustainable development and also help China to conduct further domestic reform in economic development and transition.

Funding

This research is mainly funded by Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of Chongqing Education Commission, grant number 19JD007. This research also received funding from the SMART Project.

Acknowledgments

The earlier draft of this paper was presented at the 2019 IGLP Scholars Workshop organised by the Institute for Global Law and Policy of Harvard Law School and the Thailand Institute of Justice. I would like to thank all commentators and anonymous reviewers. Any remaining errors are my own responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aseeva, A. (Un)Sustainable Development(s) in International Economic Law: A Quest for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammage, C.; Tonia, N. Sustainable Trade, Investment and Finance: Toward Responsible and Coherent Regulatory Frameworks; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. The Critical Role of Infrastructure for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://content.unops.org/publications/The-critical-role-of-infrastructure-for-the-SDGs_EN.pdf?mtime=20190314130614 (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Corning, P. The Synergism Hypothesis: On the Concept of Synergy and It’s Role in the Evolution of Complex Systems. J. Soc. Evol. Syst. 1998, 21, 133–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C. Synergy matters: Working with systems in the twenty-first century. Kybernets 2000, 29, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benecke, G.; Schurink, W.; Roodt, G. Towards A Substantive Theory of Synergy. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, Z. The Synergy Theory of Economic Growth. In The Synergy Theory on Economic Growth: Comparative Study between China and Developed Countries; Liu, J., Jiang, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, Z. Innovation-driven and investment supportive strategies for China’s economic transformation based on collaborative theory. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. &.T. 2015, 2, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yakimtsov, V. Laws of Synergy in the Economy, Business and the Operation Process of the Manufacture (Organisation). Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 1, 328–329. [Google Scholar]

- Mawle, A. Climate change, human health, and unsustainable development. J. Public Health Policy 2010, 31, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IISD. A Sustainability Toolkit for Trade Negotiators: Trade and Investment as Vehicles for Achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/toolkits/sustainability-toolkit-for-trade-negotiators/1-why-is-sustainable-development-important-for-trade-and-investment-agreements/ (accessed on 30 April 2019).

- Van Aaken, A.; Lehmann, T.A. Sustainable Development and International Investment Law: An Harmonious View from Economics. In Prospects in International Investment Law and Policy; Echandi, R., Sauve, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- Segger, M.C.C.; Gehring, M.W.; Newcombe, A. Sustainable Development in World Investment Law (Global Trade Law); Kluwer Law International: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Oppenheim, J.; Stern, N. Driving Sustainable Development through Better Infrastructure: Key Elements of a Transformation Program; Brookings Global Economy and Development Working Paper 91; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Casier, L. Why Infrastructure is Key to the Success of the SDGs. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/blog/why-infrastructure-key-success-sdgs (accessed on 30 April 2019).

- Chi, C.S.F.; Ruuska, I.; Xu, J. Environmental impact assessment of infrastructure projects: A governance perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F.; Peletier-Jellema, A.; Geenen, B.; Koster, H.; Verweij, P.; Van Dijck, P.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Schleicher, J.; Van Kuijk, M. Reducing the global environmental impacts of rapid infrastructure expansion. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, R259–R262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. How Can We Promote Sustainable Development? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/11/how-can-we-promote-sustainable-infrastructure/ (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Jessop, S.; Merriman, J. World Needs $ 94 Trillion Spent on Infrastructure by 2040: Report; Reuters: London, UK. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-infrastructure-report/world-needs-94-trillion-spent-on-infrastructure-by-2040-report-idUSKBN1AA1A3 (accessed on 30 April 2019).

- Climate Change is Driving Debt for Development Countries. Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/climate-change-is-driving-debt-for-developing-countries (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Camdessus, M. Why China’s Belt and Road must be a Path Way to Sustainable Development. South China Morning Post. 17 May 2017. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2094611/why-chinas-belt-and-road-must-be-pathway-sustainable (accessed on 30 April 2019).

- Linster, M.; Yang, C. China’s Progress Towards Green Growth: An International Perspective; OECD Green Growth Papers No. 2018/5; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Motivation, framework and assessment. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 40, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.K. Three questions on China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 40, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road; with State Council authorization; National Development and Reform Commission; Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 28 March 2015.

- Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2017; Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/asia-infrastructure-needs (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- India Kearsley. China’s Belt & Road Initiative: Infrastructure Investment for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.a4id.org/student_blog/infrastructure-investment-for-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Liu, W.; Dunford, M. Inclusive globalization: Unpacking China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Area Dev. Policy 2016, 1, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China. Yang Jiechi on the Belt and Road Initiative and Preparations for the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. Available online: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1649905.shtml (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- BRI Projects. Available online: https://www.beltroad-initiative.com/projects/ (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Wang Yi: “Belt and Road” Initiative and 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Run in Parallel with Mutual Promotion. 2017. Available online: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1478469.shtml (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Xue, L.; Weng, L.; Yu, H. Addressing policy challenges in implementing SDGs through an adaptive governance approach—A view from transitional China. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Yang, X.; Li, H. The Belt and Road Initiative and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Seeking linkages for global environmental governance. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 16, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L. Synergies between the Belt and Road Initiative and the 2030 SDGs: From the perspective of development. Econ. Political Stud. 2018, 6, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition (BRIGC). Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/regions/asia-and-pacific/regional-initiatives/belt-and-road-initiative-international-green (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Cheng, L.; Horner, S. Twenty-Seven Global Institutions Sign up to Green Investment Principles for the Belt & Road. 2019. Available online: https://beltandroad.hktdc.com/en/insights/twenty-seven-global-institutions-sign-green-investment-principles-belt-road (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Ming, B. How to deepen cooperation under BRI framework. China Daily. 9 May 2019. Available online: www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201905/09/WS5cd35c0fa3104842260ba9a1.html (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Horvath, B. Identifying Development Dividends along the Belt and Road Initiative: Complementarities and Synergies between the Belt and Road Initiative and Sustainable Development Goals. In UNDP and CCIEE Scoping Paper 1, Proceeding of 2016 High-Level Policy Forum on Global Governance, Beijing, China, 10 November 2016; CCIEE: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jointly Building the “Belt and Road” towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/policy/building-belt-road-towards-sdgs.html (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- United Nations Poised to Support Alignment of China’s Belt and Road Initiative with Sustainable Development Goals, Secretary-General Says at Opening Ceremony. Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19556.doc.htm (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- HSBC. Greening the Belt and Road Initiative: WWF’s Recommendations for the Finance Sector—In Conjunction with HSBS. Available online: https://www.sustainablefinance.hsbc.com/reports/greening-the-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Ruta, M. Three Opportunities and Three Risks of the Belt and Road Initiative. The World Bank Blogs. 4 May 2018. Available online: http://blogs.worldbank.org/trade/three-opportunities-and-three-risks-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Johnston, L. The Costs and Benefits of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Available online: https://asiancorrespondent.com/amp/2018/11/the-costs-and-benefits-of-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/ (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Ruta, M.; Dappe, M.H.; Lall, S.; Zhang, C.; Constantinescu, C.; Lebrand, M.; Mulabdic, A.; Churchill, E. Belt and Road Economics: Opportunities and Risks of Transport Corridors. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/publication/belt-and-road-economics-opportunities-and-risks-of-transport-corridors (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Xinhua. ASEAN, Including Cambodia, Hugely Benefit from BRI: Cambodian Experts. Available online: https://www.ciie.org/zbh/en/news/exhibition/News/20190809/17850.html (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- China Power Team. How will the Belt and Road Initiative Advance China’s Interests? Available online: https://chinapower.csis.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative/ (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Barton, B. The United Kingdom and the Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI) in a Post-Brexit Age: Getting the UK BRI Policy Response Right; UoN Asia Research Institute Policy Brief Background Report; Asia Research Institute, University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/asiaresearch/documents/policy-briefs/policy-report-barton.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Lal, D. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is becoming a Massive Debt Trap. Available online: https://wap.business-standard.com/article-amp/opinion/china-s-belt-and-road-initiative-is-becoming-a-massive-debt-trap-118032701301_1.html (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Hong, C.; Johnson, O. Mapping potential climate and development impacts of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A participatory approach. SEI Discussion Brief, 22 October 2018. [Google Scholar]