Abstract

The study aims to learn more about the profiles of students who attended several Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) at the University of Málaga (Málaga, Spain) and their opinion about them. The results of this study are based on a survey conducted by the students who completed the courses. The number of men and women as a whole is similar, although significant differences can be observed depending on the subject matter of the courses, which is also the case with the age of the students. The data revealed that 80% have university studies and 60% were working. The students in the sample learned about MOOCs mainly from other people (friends, social media, etc.) and showed a high level of satisfaction with them. It is significant that 99.4% would take another MOOC or that 97.9% would recommend it to a friend, colleague, or family member.

1. Introduction

The expansion of higher education worldwide was a remarkable achievement in the 20th century, rising from half a million students at the turn of the century to 100 million in 2000 [1]. This growth, which has reached its peak in some countries, has taken place in parallel with the transformations required by an ever-changing society to which the university, like the rest of the educational institutions, must respond. The mission of higher education in teaching and research must be revisited accordingly [2,3,4].

The global impact of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) such as the number of courses offered, students enrolled, etc. in recent years is indisputable, and they are a clear indicator (along with others such as methodological changes, use of open resources, etc.) of the current paradigm revolution in higher education [5,6,7,8,9]. MOOCs represent a transformation of technology for learning and an evolution of distance education [10,11]. This type of education has moved from closed educational platforms to open learning environments with the potential of thousands of people around the world following different educational initiatives through a variety of devices at the same time [12,13].

There are multiple definitions of MOOCs [14,15,16] and they share many common characteristics [17]. MOOCs are basically a combination of lectures in audio or video format (no longer than 10 to 15 min) and text documents which are accessible online. MOOCs also contain assignments (usually questionnaires) automatically marked by the platform on which they are hosted or by other students enrolled in the same course. Sometimes students have to pass tests to make further progress in the content. There are no limits, however, on the number of students who can register for a given course, so there is either minimal or no tutorial work by the course teachers [18,19]. The responsibility for learning is distributed among the students in the course [20] or facilitators [21] mainly through fora. There is also no impediment to taking a MOOC. In fact, they were initially created with the idea of democratizing higher education, allowing many people [22] to access courses who would not otherwise have been able to [23]. The courses are taught by prestigious professors of higher education [9]. Some MOOCs may even have a final exam or assignment to pass, and some sort of certificate or diploma can be issued upon completion [24].

Within the MOOCs, they have distinguished between the so-called xMOOCs, which are linear and focused on guided lessons by instructors and automated tests to verify the understanding of the contents, and the cMOOCs, which focus more on shaping learning communities that create knowledge together [14,25,26].

Due to their characteristics, these courses are distributed all over the world and can be innovative [27,28,29] only if it is verified that they are focused as experiments to experience new methodologies, new technologies, and new ways of organizing education [26]. In spite of everything, it has the same potential as other online learning experiences since MOOCs can be endowed with a solid pedagogical basis [30].

There is no doubt that its pedagogical design is fundamental and essential for the implementation of an MOOC to the extent that it guides, organizes, structure, systematizes, and explicitly and publicizes the training action that is carried out [31]. Downes [32] argues that four fundamental principles must be taken into account: autonomy, diversity, openness, and interactivity. These are fundamental when planning learning activities, materials, and a participation structure that brings real value. Therefore, it seems evident that pedagogically effective courses give rise to a richer learning experience and ensure their quality assurance [28].

The MOOC phenomenon has received considerable attention in recent years from the scientific literature [33,34,35], but also from students, teachers, educational institutions, and the media. It would not be wrong to say that MOOCs have arrived “to stay”, as evidenced by the more than 500,000 people enrolled in a course at Udacity or the more than five million enrolled in one at Code Academy [36]. Even though they have gone from an initial euphoria with nothing but positive acknowledgements and praises, to a stage of some criticism (with respect to the evaluation, the methodology, the low transformation impact they are really having, the commercial nature of some, their quality, to the fact that it reproduces in new ways the digital divide if we take into account that access is being unequal depending on the profiles that students, etc.), continuous research is necessary on the subject [37,38]. Like any other phenomenon, the MOOC phenomenon will change and transform over the years until it leads towards other models that are unlike the current one [39].

Different organizations (companies, foundations supported by banking entities, and universities) that put up personnel and resources, sometimes with the sole purpose of gaining visibility, have been the driving force behind these phenomena. Therefore, even though MOOCs came about for altruistic purposes [26], these organizations inevitably considered whether they can maintain these initiatives or propose different ones. The number of universities offering MOOCs is growing [7], although it is difficult to charge them with the task that higher education institutions have traditionally been entrusted with, as they would drift from their teaching role to become accrediting bodies through examinations. However, experiences were found where MOOCs were used as an instrument to support formal education, thus improving the results achieved by students and reducing the percentage of students who did not manage to pass the subject [40,41], although they do not replace formal education at present [42]. In a future scenario, skills-based online education is likely to compete even more closely with traditional forms of education as far as accessibility, affordability, and quality are concerned.

These institutions must carry out a study on the people who register with them and their opinions. Those who develop these lines of research have focused their attention on the high drop-out rates [43,44,45] or the perception they have of the students [46], but few have dedicated time to define the profile of the students interested in MOOCs or consider the assessment they make of them, mainly because there are authors who claim the quality and depth of the training is not as expected [4,47,48].

Another issue universities that teach MOOCs focus on is certification. Being able to certify education enters into conflict with their original philosophy, which is merely formative and of a non-accreditation nature [49]. However, the new scenario is indeed taking shape due to its potential attraction of both of students and income with initiatives, such as logos on the platforms where MOOCs are developed [50] or certificates from universities that pay for their processing. This is also the case of the UNED, the Autonomous University of Madrid, etc.

This study analyses the xMOOCs promoted by a university in Spain, namely the University of Málaga (UMA) to learn more about:

- Students who enroll in xMOOCs, considering personal variables such as sex, age, employment situation, country of origin, previous experience, and the medium through which they learned about the training activity.

- The evaluation they make of the MOOCs and their degree of satisfaction with the training process, especially the evaluation based on questionnaires and among peers.

The data collected will be used to adapt these types of training activities to the needs of potential students and the entities that offer them, and to improve their quality and content.

2. Context

The University of Málaga mainly teaches face-to-face. However, it was considered a priority and strategic to participate in the implementation of several xMOOCs in order to respond to their social responsibility, by giving back to society, free of charge and openly, part of the knowledge generated within it, on the one hand. On the other, it was to achieve a greater international projection for the institution.

To this end, since 2013, there have been several public calls for proposals for the selection and implementation of various xMOOCs, and the necessary human and material resources were made available to the selected projects.

At the end of 2017, Miríadax hosted a total of seven xMOOCs. Each of them, according to the call of the UMA, should have the following qualities: lasting between six and nine weeks, be structured in modules to facilitate the monitoring of the contents, each module should contain videos subtitled and narrated by the teacher, theoretical support material (external links, files, documents and related readings, etc.) and activities and tasks to apply the contents of the module. At the end of each module, an assessment of knowledge through questionnaires would be included. The evaluation instruments were questionnaires, mandatory completion, and peer-rating tasks (P2P—peer-to-peer). The latter were voluntary.

The MOOCs were published in Miríadax, almost all of them in several editions (Table 1). Miríadax is the MOOCs website of reference in the Spanish language, offering courses from 45 Latin American universities and catering for one and a half million students in 2018.

Table 1.

MOOCs and editions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The participants of this study were students who studied and completed the xMOOCs offered by the UMA (except one of them: Mediterranean, where no evaluation questionnaire was applied) and developed on the Miríadax platform (Table 2). Therefore, a non-probabilistic (accidental) sampling was carried out.

Table 2.

Students of the xMOOCs of the University of Málaga, who started and completed the questionnaire.

The completion rates of Table 2 refer to students who started the MOOC, not just those who enrolled.

At the end of the training process, the research team sent the invitation to participate in the study to students who completed the MOOCs (invited sample). The total number of participants was 10,454, representing 11.26% of those who started the course (93,577 if we exclude the MOOC on Knowing the Mediterranean) or 48.44% of those who actually completed a MOOC.

3.2. Instruments

Data were collected through a questionnaire, prepared ad hoc by the research team, located in the last tab of each course and filled out voluntarily (not being a compulsory task for the completion of the course).

The questionnaire was designed by a discussion group that, following León y Montero [51], met up during several discussion sessions. In the first one, the type of questionnaire was defined (areas of interest, number of items, writing style, rating scale, and presentation format). The questionnaire was then passed on to a pilot sample of people who had tested each MOOC item. In the second session, they created the final wording of each of the items and decided on their arrangement in the questionnaire.

The resulting product was subjected to an expert consultation (Delphi method), which completed the construction of the tool, thus achieving a high degree of validity for the purpose of the survey.

Once the validation process was completed, the questionnaire was computerized through the Google Drive forms application. Different types of questions were designed, such as multiple choice, closed and open. In addition to the course evaluation questions (for which a 4-point Likert scale was used), data were collected from students regarding sex, age, educational level, employment status, country, whether they had done any online activities before, whether they had done any MOOCs before, how they knew about the course, and whether they would do any MOOCs again.

The reliability of the questionnaire was analyzed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The score achieved was 0.87, which allowed establishing the internal consistency of the instrument.

4. Results

A bivariate analysis of variables has been carried out using the x2 test.

xMOOC students were of different profiles, ranging from high school students to retirees seeking new learning opportunities.

The number of men (n = 5237, 50.1%) and women (n = 5217, 49.9%) is practically identical (Table 3). There are, however, significant differences in the sex and subject matter of xMOOCs (x2(5, N = 10,454) = 1057.73, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Distribution within xMOOCs by sex (% within MOOC).

In terms of age, the largest group is ages 36–45 and the smallest is children under 19 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution within xMOOCs by age (% within MOOC).

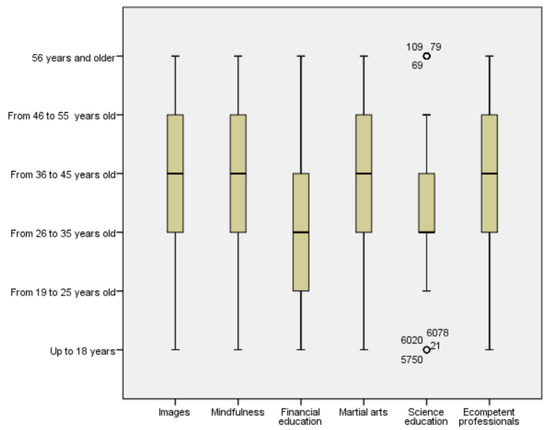

Again, significant differences can be seen between xMOOC topics and age (x2(25, N = 10,454) = 519.04, p < 0.001). For example, Martial Arts for the under 19 age group or Mindfulness among people aged 46 to 55 and 56 and over (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution by age.

With regard to the level of studies, it should be noted that 78.7% have university studies (Table 5) and there are significant differences with sex (x2(2, N = 10,454) = 113.59, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Level of education by sex (% within sex).

Regarding their employment situation (Table 6), most of them had a job (46.34% employees -B- and 13.26% self-employed -C-), followed by the unemployed (19.96% -D-). The lowest percentages corresponded to students (17.11% -A-) and pensioners (3.3% -E-).

Table 6.

Employment situation by age bracket (% within employment situation).

Logical data can be seen, such as the fact that the highest number of pensioners is in the over 56 age group, or that the percentage of students is higher in the under 18 age group than in other employment situations.

As for the country of residence is concerned, almost all of them came from Spanish-speaking countries in Europe and America. Spain was the country that contributed the most students.

With regard to previous experience in online training activities, 84.06% indicated that they had done at least one, and 55.6% of those with experience in online training activities had participated in more than four activities beforehand (Table 7).

Table 7.

Previous online training activities.

With regard to the experience with MOOCs, 42.84% of them were first-timers, and 45.4% of those who had already done one had participated in more than four MOOCs (Table 8).

Table 8.

Number of MOOCs you have done.

Students heard about MOOCs mainly through other people (26.3% through friends, acquaintances, colleagues and 25.2% through social media) and through the platform itself (23.1%) (Table 9).

Table 9.

How did you find out about the MOOCs you have enrolled in?

Focusing on the evaluation of the MOOCs, a 4-point Likert scale has been used for some items: 1 = Disagree; 2 = Partially disagree; 3 = Partially agree and 4 = Strongly agree). For other dichotomous items, a simple yes or no was used.

Most students attained the objectives that had been set when they registered in the MOOC (64.8%). The percentage rises to 97.4% when considering partially achieved objectives (Table 10). The answers are similar in all MOOCs.

Table 10.

Have the objectives of this course been achieved? (% within MOOCs).

Similar percentages were obtained when asked about whether the course objectives were consistent with the content (Table 11), whether students considered the contents to be well-founded and rigorous (Table 12), and whether the contents reached the expected depth (Table 13).

Table 11.

Are the objectives of the course consistent with the content? (% within MOOCs).

Table 12.

Have the contents been well-founded and rigorous? (% within MOOCs).

Table 13.

Have the contents been as detailed as you expected? (% within MOOCs).

On the evaluation of MOOCs, 95.9% consider it to be in line with the duration and content of the courses (Table 14).

Table 14.

Do you consider the evaluation is in line with the materials and duration of the course? (% within MOOCs).

Open-ended questions were used for these two sections, and the answers were then categorized. Regarding the questionnaires, 70.1% considered their use to be adequate and correct, and 25.6% considered them to be very adequate (Table 15). If both percentages are added together, 95.7% consider the use of questionnaires in MOOCs to be adequate or very adequate. Of the voluntary P2P tasks, 9.8% did not send them, and of the remaining 90.2%, 12.6% considered them excellent, and 36.3% considered them quite useful (Table 16). Less than 20% considered them non-adequate.

Table 15.

What do you think about the evaluation of the course being carried out by questionnaires?

Table 16.

What is your opinion of peer-to-peer review?

The tutoring of the MOOCs was carried out through fora and by fellow students of the courses because the volume of students of the MOOCs made it impossible for the authors of the courses to follow them personally. The fact that it was the colleagues themselves who answered the questions was rated positively (very good or good) by 75.9% of the students.

Nevertheless, 39.3% (n = 4110) would have liked a tutor assigned to a group of students for follow up, compared to 60.7% (n = 6344) who responded negatively.

There is unanimity as to whether they would do a MOOC again since 99.4% (n = 10,388) would do another MOOC again while 0.6% (n = 66) would not. On whether they would recommend the MOOC to a friend, colleague, or family member, 97.9% (n = 10,235) would recommend it, compared to 2.1% (n = 219) who would not.

Finally, students were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with the MOOC. Most of them indicated that they were very satisfied (54.5%) or satisfied (42.5%).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

MOOCs are promoting democratization and the accessibility of knowledge worldwide. Therefore, universities must contribute to its implementation as a system of lifelong learning that complements their training [4].

In this sense, UMA considers the xMOOC offering. As with other educational centres [9,52,53,54,55], the drop-out rate for xMOOCs in the UMA was high (76.9% of students who started xMOOCs did not finish them). We attribute the cause to the very characteristics of this type of course: free of charge, no time requirements, no official certification for students who complete it, etc.

This paper has focused on getting to know some of the dimensions of MOOCs to contribute information to the debate on this type of training activities that seem to have great potential for the expansion of knowledge.

Concerning the objective of learning more about the students who enroll in MOOCs, the number of men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) is almost identical [52,56,57], although there is a significant difference in the topics of MOOCs they choose. These differentiated preferences also happen by age groups.

In line with other studies [58,59], most of the participants were adults. 29.2% were between 26 and 35-years-old, and 28% were between 36 and 45-years-old. The latter percentage is quite high considering that MOOCs target a wide range of populations outside formal education.

Most MOOC students (78.7%) had university studies, followed by those who had completed secondary education [58]. Finally, with an almost anecdotal presence, we find students with primary education diplomas. This sequence leads us to conclude that the higher the level of study, the more interest there is in MOOCs.

Regarding the place of residence, almost all of the students came from Spanish-speaking countries in Europe and America as the MOOCs were in Spanish, which confirms that language is a crucial aspect [57] in the sense that students seek training activities in their native language.

With regard to the students’ assessment of MOOCs and their satisfaction with the MOOC process, the conclusion is that they were very satisfied with the MOOCs [15,52,60]. Previous experience in online training activities in general and MOOCs, in particular, is positive for the students, as most of them have participated in more than four activities before. A high percentage of students attained the objectives that had been set when they registered in the MOOC (64.8%). The percentage rises to 97.4% when considering partially achieved objectives. Almost 100% indicate that they fully or partially agree that the objectives of the course are consistent with the content and that the content was well-founded and rigorous. It is, therefore, not surprising that 97.9% of students would recommend the MOOC they completed [15].

While MOOC tutoring was conducted using peer fora, this was rated positively by 75.9% of students [58]. However, 39.3% would have liked a tutor assigned to a group to support them in their progress. Therefore, progress could be made in solving the problems of the individual differences of each student inherent to the current massification of the MOOCs, which involves a unidirectional, teacher-centred, and content-based communicative design.

As regards the rating of the MOOCs, 95.7% consider the use of questionnaires to be adequate or very adequate, and 48.9% indicate that the P2P tasks are excellent and quite useful.

On how they have known about the existence of the MOOC they completed, 51% found out through other people (friends, acquaintances, relatives, or social media).

Finally, we can say that despite the fact that MOOCs have broken into mass-based network training, there is still a relevant leap in pedagogical terms. We agree with Roig Vila, Mengual-Andrés & Suárez Guerrero [61] that the MOOCs have not yet generated a break with the online training models of e-learning. Despite this, it is clear that the task is not only pedagogical, but it is no less true that without it, it will not be possible to identify the disruptive elements to be addressed in learning and network education.

6. Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations of this study, including the boundaries of a single platform (Miríadax), the several Spanish language xMOOCs from a single university, the sampling bias inherent in the fact that the surveys were voluntary and that, since only those who completed the survey completed them, there is no information about those who did not complete them. The results cannot be generalized to other language learners who have taken courses on other platforms. Despite these limitations, the heterogeneity of situations, countries, etc. of the students guarantees the criteria of representativeness necessary to advance in the understanding of the profile of the participants in these types of courses and their evaluations and personal satisfaction.

In the light of the results of this research, the possibilities of MOOCs in current university teaching must be considered in further depth, and new ways of incorporating this type of training should be explored, which would imply responding to the authenticity and reliability of the students’ evaluations.

Moreover, if one of the responsibilities of the university is to give back to society part of the knowledge generated within it, attention must still be paid to the fact that the profiles of students who complete MOOCs are unequal. This promotes a new digital divide, since it benefits an elitist, academic, and professional community, belonging mostly to developed countries [53,57,62].

We recommend the scientific community deepen their knowledge of MOOCs, a training modality that is very attractive for students, increases academic performance [40,63], and allows autonomous learning and personalized access to information [64].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.-P.; Data curation, J.R.-P.; Investigation, J.R.-P.; Methodology, E.S.-R.; Resources, D.L.-Á. and J.S.-R.; Validation, D.L.-Á. and J.S.-R.; Writing—original draft, E.S.-R.; Writing—review & editing, D.L.-Á.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schofer, E.; Meyer, J.W. The Worldwide Expansion of Higher Education in the Twentieth Century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorno, D.M.; Benítez, Á.M. La nueva misión de la universidad. Contextualización y resultados: Casos de tres universidades públicas colombianas. Panorama 2017, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pérez, S.; Castaño, R. Funciones de la Universidad en el siglo XXI: Humanística, básica e integral. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2016, 19, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, C. El MOOC: ¿un modelo alternativo para la educación universitaria? Apert. Rev. Innovación Educ. 2015, 7, 110–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jee, H.A. A Study for Direction of the Character Education in University according to the Fourth Industrial Revolution Era. Korean J. Gen. Educ. 2017, 11, 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, A.B. Cambio organizacional y cambio en los paradigmas de la administración. Iztapalapa 2018, 21, 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M. State of the MOOC 2017: A Year of Privatized and Open Education Growth. Online Course Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.onlinecoursereport.com/state-of-the-mooc-report/ (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Taatila, V. Paradigm shift in higher education? Horizon 2017, 25, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubell, R. How the Pioneers of the MOOC Got It Wrong. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-talk/at-work/education/how-the-pioneers-of-the-mooc-got-it-wrong (accessed on 16 May 2018).

- Flynn, J.T. MOOCS: Disruptive innovation and the future of higher education. Christ. Educ. J. 2013, 10, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.J.; Fidalgo, Á.; Sein, M.L. Los MOOC: Un análisis desde una perspectiva de la innovación institucional universitaria. Cuestión Univ. 2017, 9, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. Active learning through student film: A case study of cultural geography. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2013, 37, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Caldwell, H.; Richards, M.; Bandara, A. A comparison of MOOC development and delivery approaches. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2017, 34, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero, J.; Llorente, M.C.; Vázquez, A.I. Las tipologías de MOOC: Su diseño e implicaciones educativas. Profesorado. Rev. Curríc. Y Form. Profr. 2014, 18, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- González, Á.; Carabantes, D. MOOC: Medición de satisfacción, fidelización, éxito y certificación de la educación digital. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. A Distancia 2017, 20, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Toven, B.; Rhoads, R.A.; Lozano, J.B. Virtually unlimited classrooms: Pedagogical practices in massive open online courses. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.A.; Rodríguez, C.; Fernández, E.M. ¿Cómo son los MOOC sobre educación? Un análisis de cursos de temática pedagógica que se ofertan en castellano. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2016, 29, 298–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo, Á. ¿Qué es un MOOC? Innovación Educativa. 2012. Available online: https://innovacioneducativa.wordpress.com/2012/12/14/que-es-un-mooc/ (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Wilson, J. What You Need to Know about MOOCs. Available online: http://www.chronicle.com/article/What-You-Need-to-Know-About/133475/ (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Pardo, J.Á.; Reinoso, A.J. Mooc o cursos masivos abiertos en línea. Interactividad comunicativa y multimedias. Diseño e implementación. Expectativas y consideraciones prácticas. Tecnol. Desarro. 2016, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Marauri, P.M. Figura de los facilitadores en los cursos online masivos y abiertos (COMA / MOOC): Nuevo rol profesional para los entornos educativos en abierto. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2014, 17, 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, A.; Hood, N.; Milligan, C.; Mustain, P. Learning in MOOCs: Motivations and self-regulated learning in MOOCs. Internet High. Educ. 2016, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, M.R.; Christensen, C.M. Hire Education: Mastery, Modularization, and the Workforce Revolution; Clayton Christensen Institute: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-5005-5312-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, M.; Ebner, M. La certificación de los MOOC. Ventajas, desafíos y experiencias prácticas. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2017, 75, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is a MOOC? What are the different types of MOOC? xMOOCs and cMOOCs. Available online: https://reflectionsandcontemplations.wordpress.com/2012/08/23/what-is-a-mooc-what-are-the-different-types-of-mooc-xmoocs-and-cmoocs/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Pernías, P.P.; Luján Mora, S. Los MOOC: Orígenes, historia y tipos. Comun. Pedagog. Nuevas Tecnol. Recur. didácticos 2013, 269–270, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.; McGreal, R. Disruptive Pedagogies and Technologies in Universities. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2012, 15, 380–389. [Google Scholar]

- Conole, G. MOOCs as disruptive technologies: Strategies for enhancing the learner experience and quality of MOOCs. RED—Revista de Educación a Distancia 2013, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cano, E.; López-Meneses, E.; Sarasola, J.L. La Expansión del Conocimiento en Abierto: Los MOOC; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glance, D.G.; Forsey, M.; Riley, M. The pedagogical foundations of massive open online courses. First Monday 2013, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M. Orientaciones pedagógicas para los MOOC. In Creación de Cursos MOOC Con Anotaciones Multimedia; Cebrián de la Serna, M.D., Ed.; Gtea: Málaga, Spain, 2017; pp. 22–34. ISBN 978-84-695-9562-6. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, S. The Quality of Massive Open Online Courses. Available online: https://www.downes.ca/cgi-bin/page.cgi?post=66145 (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Cabero, J.; Marín, V.; Sampedro, B.E. Aportaciones desde la investigación para la utilización educativa de los MOOC. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2017, 75, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duart, J.M.; Roig, R.; Mengual, S.; Maseda, M.Á. La calidad pedagógica de los MOOC a partir de la revisión sistemática de las publicaciones JCR y Scopus (2013–2015). Rev. Española Pedagog. 2017, 75, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancanaro, A.; Domingues, M.J. Analysis of the scientific literature on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)/Análisis de la literatura científica sobre los cursos en línea abiertos y masivos (MOOC). RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2017, 20, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OnlineCourses.com 10 Best Online Courses of 2016. Available online: https://www.onlinecourses.com/ (accessed on 16 May 2018).

- Cabero, J.; Llorente, M.C. Los MOOC: Encontrando su camino. @tic. Rev. D’innovació Educ. 2017, 18, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- García, L. MOOC: ¿tsunami, revolución o moda pasajera? RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2015, 18, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M. MOOCs, una visión crítica y una alternativa complementaria: La individualización del aprendizaje y de la ayuda pedagógica. Campus Virtuales 2013, 2, 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado, J.C. ¿Pueden los MOOC favorecer el aprendizaje y hacer disminuir las tasas de abandono universitario? RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2017, 20, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi, S.; Tanaka-Ellis, N. Integrating a Mooc in a Japanese University Curriculum with a Flipped Classroom Approach: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the INTED2017: 11th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Alencia, Spain, 6–8 March 2017; pp. 7493–7496, ISBN 978-84-617-8491-2. [Google Scholar]

- Faizi, R.; El Fkihi, S.; Chiheb, R. Can Moocs Replace Formal Education? In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (iceri2017), Seville, Spain, 16–18 November 2017; pp. 7276–7280, ISBN 978-84-697-6957-7. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrog, L. 2013-the Year of ups and Downs for the MOOCs. Available online: http://www.changinghighereducation.com/2014/01/2013-the-year-of-the-moocs.html (accessed on 30 June 2017).

- Eriksson, T.; Adawi, T.; Stöhr, C. “Time is the bottleneck”: A qualitative study exploring why learners drop out of MOOCs. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017, 29, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veletsianos, G.; Shepherdson, P. A Systematic Analysis and Synthesis of the Empirical MOOC Literature Published in 2013–2015. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2016, 17, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, C.M.; Maiz, I.; Garay, U. Percepción de los participantes sobre el aprendizaje en un MOOC. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2015, 18, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Margaryan, A.; Bianco, M.; Littlejohn, A. Instructional quality of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, Ó.; González, F.; García, M.Á. Propuesta de evaluación de la calidad de los MOOCs a partir de la Guía Afortic. Campus Virtuales 2013, 2, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, E.; Méndez, J.M.; Román, P.; López, E.J. Diseño y desarrollo del modelo pedagógico de la plataforma educativa “Quantum University Project”. Campus Virtuales 2015, 2, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo-Rivas, M.; Martínez-Figueira, E.; Sarmiento-Campos, J.A. Un estudio sobre los componentes pedagógicos de los cursos online masivos. Comunicar 2015, 22, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, O.G.; Montero, I. Métodos de Investigación en Psicología y Educación; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2002; ISBN 978-84-481-3670-3. [Google Scholar]

- González, Á.; Casaravilla, A.; Fernández, T. Aproximación al abandono en los cursos online masivos y gratuitos MOOC. In Proceedings of the Congresos CLABES, Córdoba, Argentina, 15–17 November 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Poy, R.; Gonzales-Aguilar, A. Factores de éxito de los MOOC: Algunas consideraciones críticas. RISTI Rev. Ibérica Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2014, e1, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ye, C.; Biswas, G. Early Prediction of Student Dropout and Performance in MOOCSs Using Higher Granularity Temporal Information. J. Learn. Anal. 2014, 1, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenghao, C.; Alcorn, B.; Christensen, G.; Eriksson, N.; Koller, D.; Emanuel, E.J. Who’s Benefiting from MOOCs, and Why. Available online: https://hbr.org/2015/09/whos-benefiting-from-moocs-and-why (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Emanuel, E.J. Online education: MOOCs taken by educated few. Nature 2013, 503, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.D.; Chuang, I.; Reich, J.; Coleman, C.A.; Whitehill, J.; Northcutt, C.G.; Williams, J.J.; Hansen, J.D.; Lopez, G.; Petersen, R. HarvardX and MITx: Two Years of Open Online Courses Fall 2012-Summer 2014. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2586847 (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Callejo, J.; Agudo, Y. MOOC: Valoración de un futuro. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2018, 21, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobarra, L.; Ros, S.; Hernández, R.; Robles-Gómez, A.; Pastor, R.; Caminero, A.C.; Cano, J.; Claramonte, J. Analyzing Students’ Behavior in UNED-COMA MOOCs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Learning Analytics Summer Institute Spain 2017: Advances in Learning Analytics, Madrid, Spain, 4–5 July 2017; pp. 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, M.D.; Yot, C.; Aguaded, J.I. La motivación del alumnado como eje vertebrador en la era Post-MOOC. @tic. Rev. D’innovació Educ. 2017, 18, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Roig Vila, R.; Mengual-Andrés, S.; Suárez Guerrero, C. Evaluación de la calidad pedagógica de los MOOC. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2014, 18, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, L. Annual Report 2014–2015. Available online: http://docplayer.net/1358780-2014-2015-annual-report.html (accessed on 2 June 2018).

- Paz, V.; Zepeda, J.E. Implementación de un MOOC en cursos presenciales como estrategia para elevar el rendimiento académico. Innoeduca Int. J. Technol. Educ. Innov. 2016, 2, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Del Moral, M.E.; Villalustre, L. MOOC: Ecosistemas digitales para la construcción de PLE en la Educación Superior. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2015, 18, 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).