The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical Design of a Teacup

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background Information

1.2. Motives and Objectives

- The impact of utensil design on the intensity of tea taste.

- The impact of utensil design on the bitterness of tea.

- The impact of utensil design on the astringency of tea.

- The impact of utensil design on the sweet aftertaste of tea.

- The impact of utensil preference on the overall presentation of tea.

1.3. Research Subjects

1.3.1. The Way of Tea Drinking, and Tea-Drinking Utensils

1.3.2. Sensory Evaluation of Tea

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impact of Visual Cues on Taste

2.2. The Visual Significance of Chinese Teacups

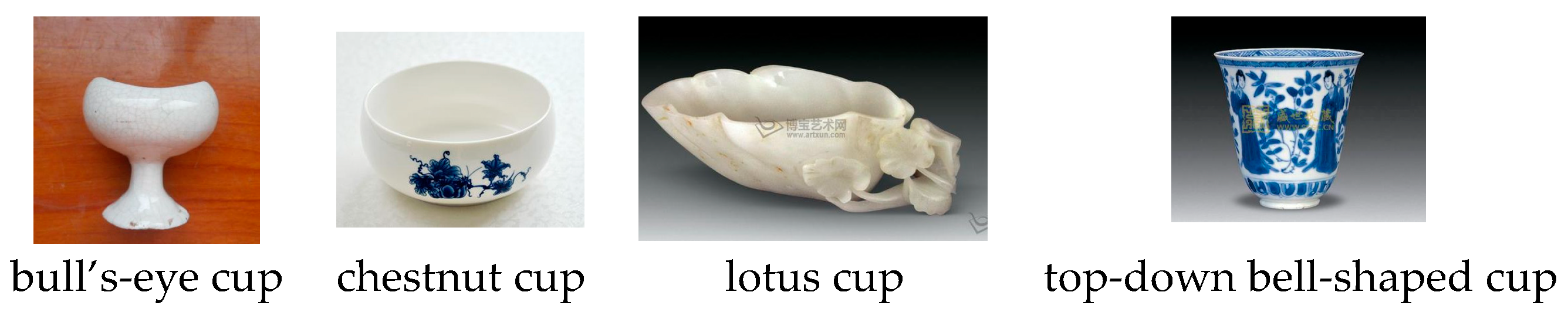

2.3. Outer Appearance and Design of Tea Vessels

2.4. Color of Vessel

2.5. Impact of Tactile Cues on Taste

3. Research Method

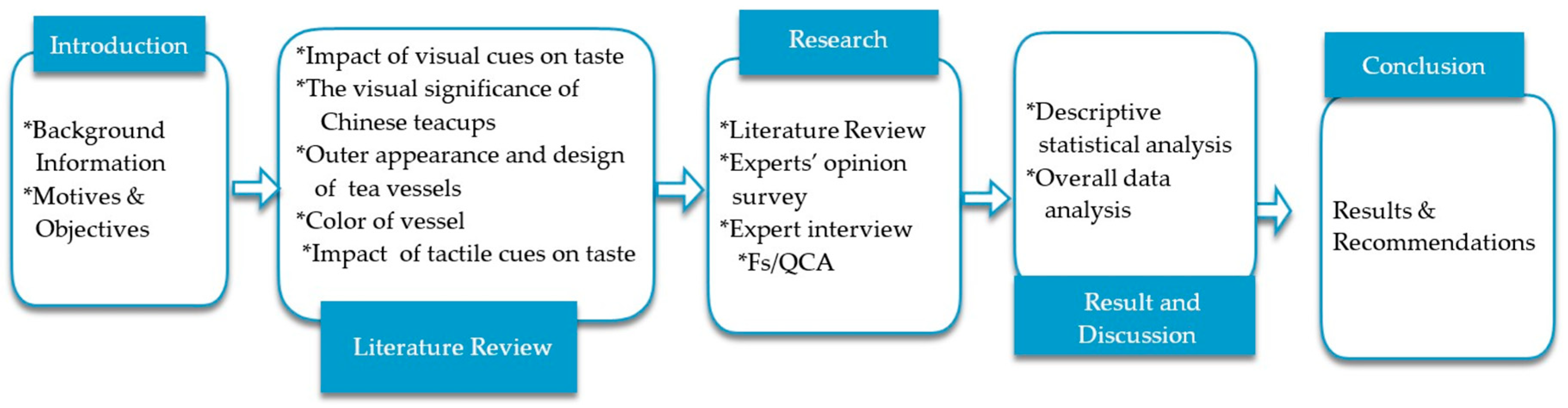

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Experiment Design

3.2.1. Subjects

3.2.2. Experimental Materials

3.2.3. Objectives

Visual

Tactile

3.2.4. Questionnaire

3.2.5. Experimental Environment

3.2.6. Experimental Operation

3.3. Fuzzy Set/Qualitative Comparative Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Fs/QCA Statistical Analysis

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.1.2. Comprehensive Data Analysis

4.2. Expert Interviews

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J. (Ed.) The 2018 China Tea Industry Development Report; China Tea Marketing Association: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Debra, L. Design for sustainable behaviour: Strategies and perceptions. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 704–720. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, R.U.; Knees, A.V. Production, consumption, and externalities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 282–297. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.; Bhamra, T. Putting consumers first in design for sustainable behaviour: A case study of reducing environmental impacts of cold appliance use. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2012, 5, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Da Rocha, C.G.; Ribeiro, J.L.D. Design for sustainable behavior (DfSB): Analysis of existing frameworks of behavior change strategies, experts’ assessment and proposal for a decision support diagram. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, N.; Hekkert, P.; Verbeek, P.P. Design for socially responsible behavior: A classification of influence based on intended user experience. Des. Issues 2011, 27, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective; John Wiley Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche, J.F. You eat with your eyes first. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, P.C.; Goss, E. Plate shape and colour interact to influence taste and quality judgements. Flavour 2013, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Exploring implicit and explicit cross modal colour-flavour correspondences in product packaging. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 25, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.T.; Poliakoff, E.; Lloyd, D.M.; Kuenzel, J.; Hodson, R.; Gonda, H.; Batchelor, J.; Dijksterhuis, G.B.; Thomas, A. Effect of background noise on food perception. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Spence, C. The Influence of the color of the cup on consumers’ perception of a hot beverage. J. Sens. Stud. 2012, 27, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Allcaide, J.; Roura, E.; Spence, C. Is the plate or is it the food? Assessing the influence of the color (black or white) and shape of the plate on the perception of the food placed on it. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 24, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrot, G.; Brochet, F.; Dubourdieu, D. The color of odors. Brain Lang. 2001, 79, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogenkamp, P.S.; Stafleu, A.; Mars, M.; Brunstrom, J.M.; De Graaf, C. Texture, not flavor, determines expected satiation of dairy products. Appetite 2011, 57, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, G.M. Smell images and the flavour system in the human brain. Nature 2006, 444, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, D.M.; Voss, J.; Mak, Y.E.; Simmons, K.B.; Parrish, T.B.; Gitelman, D.R. Experience-dependent neural integration of taste and smell in the human brain. J. Neurophysiol. 2004, 92, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Giboreau, A.; Spence, C. Assessing the influence of the color of the plate on the perception of a complex food in a restaurant setting. Flavour 2013, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielby, L.H.; Kildegaard, H.; Gabrielsen, G.; Edelenbos, M.; Thybo, A.K. Adolescent and adult visual preferences for pictures of fruit and vegetable mixes—Effect of complexity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Siemers, E.; Teran, V.; Conroy, R.; Lankford, M.; Agrafiotis, A.; Ambrose, L.; Locher, P. Neatness counts. How plating affects liking for the taste of food. Appetite 2011, 57, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Lankford, M.; Ambrose, L.; Locher, P. Art on the plate: Effect of balance and color on attractiveness of, willingness to try and liking for food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazzana, A.; Larsson, M.; Hoffmann, E.; Hummel, T.; Haehner, A. The vessel’s shape influences the smell and taste of cola. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, G.H.; Woods, A.; Levitan, C.A.; Wan, X.; Velasco, C.; Bernal-Torres, C.; Spence, C. Does the Shape of A Cup Influence Coffee Taste Expectations? A Cross-Cultural, On-Line Study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Wan, X. Beverage perception and consumption: The influence of the container on the perception of the contents. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, G.H.; Wuillemin, D.; Spence, C. Does the Colour of the Mug Influence the Taste of the Coffee? Flavour 2014, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Velasco, C.; Michel, C.; Mu, B.; Woods, A.T.; Spence, C. Does the type of receptacle influence the crossmodal association between colour and flavour? A cross-cultural comparison. Flavour 2014, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wood, A.; Seoul, K.-H.; Butcher, N.; Spence, C. When the shape of the glass influences the flavour associated with a coloured beverage: Evidence from consumers in three countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Wan, X. Assessing the Influence of the Drinking Receptacle on the Perception of the Contents. In Multisensory Flavor Perception: From Fundamental Neuroscience through to the Marketplace; Piqueras-Fiszman, B., Spence, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 269–295. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, R.Z. Modern Tea Taoist Thought; Taiwan Commercial Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Z.X. The Beginning of Teacup Beauty; Artist Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Y. Development History of Tea Art in Taiwan; Chenxing Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Madge, P. Design, Ecology, Technology: A Historiographical Review. J. Des. Hist. 1993, 6, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, V. Design, the Future and the Human Spirit. Des. Issue 2007, 23, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodham, J.M. Twentieth-Century Design; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tromp, N. Social Design-How Products and Services Can Help Us Act in Ways That Benefit Society. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cuenca, J.L.; Mayorga, M.; Romero-Salazar, L.; Yee-Madeira, H.T.; Jiménez-Gallegos, J.; Arteaga-Arcos, J.C. Advances in the use of the steel industry by-products when manufacturing traditional ceramics for sustainable purposes. Procedia Eng. 2015, 118, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United National Sustainable Development Goals. n.d. Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Tukker, A.; Emmert, S.; Charter, M.; Vezzoli, C.; Sto, E.; Munch Andersen, M.; Geerken, T.; Tischner, U.; Lahlou, S. Fostering change to sustainable consumption and production: An evidence based view. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Bhamra, T. ‘Design beyond Borders’: International collaborative projects as a mechanism to integrate social sustainability into student design practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 23, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daae, J.; Boks, C. A classification of user research methods for design for sustainable behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.R.; Jakiela, M.J. Automated product concept design: Unifying aesthetics and engineer. Comput. Graph. Appl. 1993, 13, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Pasinelli, M.; Brem, A. Prototyping in theory and in practice: A study of the similitude and differences between engineers and designers. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.; Spoedt, H. Same same but different: Perspectives on creativity workshops by design and business. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2017, 45, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 40, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, R.; Van Kuijk, J.; Boks, C. User-centred design for sustainable behaviour. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2008, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Treatise on Tea; Jiuzhou Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, S.S. Tea Shu; Collected in the New Edition of Series Integration; Xinwenfeng Publishing Company: Taibei, Taiwan, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H.D. Chaozhou Tea Classic. Available online: http://www.docin.com/p-1510003177.html (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- Tea Industry Improvement Farm of the Agricultural Committee of the Executive Yuan. Available online: https://www.tres.gov.tw/view.php?catid=1679.2018 (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Fan, Z.P. The Theory of Tea Art; Yuan Juan Lo Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.H.; Yang, D.M. Introduction to Visual Communication Design; Quanhua Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.L.; Chen, J.H.; Yan, Z. A Preliminary Study on the Construction of “Five Senses” Design Model—Taking Food Packaging Design as an Example. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Technol. J. 2008, 17, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.; Frederick, S.; Ariely, D. Try it, you’ll like it: The influence of expectation, consumption, and revelation on preferences for beer. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.M. Cognitive Psychology; Laureate Book Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrise, F.; Graziosi, S.; Bordegoni, M. Prototyping strategies for multisensory product experience engineering. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 28, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P. Haptics for product design and manufacturing simulation. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2016, 9, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Tactile/Haptic Aspects of Multisensory Packaging Design. In Multisensory Packaging; Velasco, C., Spence, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M.; Bouton, M.E. Theories of Associative Learning in Animals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, P.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Introducing product experience. In Product Experience; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, M. Brand Sense: How to Build Powerful Brands through Touch, Taste, Smell, Sight, and Sound. Strateg. Dir. 2005, 22, 278–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.Z. Research on the Cause Design of the Blind from the Perspective of Human Sensory Characteristics. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Industrial Design, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shunyi, N. The Secret of Color—An Introduction to the Latest Colorology; Spring and Autumn of Literature and Art: Tokyo, Japan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schifferstein, H.N.J. The drinking experience: Cup or content? Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F. Design Aesthetics; Quanhua Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Su, W.Q.; Yan, Z.; Li, C.F. Research on the Application of Basic Theory of Semiotics and Cognitive Psychology in Visual Design-Taking “Logo Design” as an Example. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2007, 3, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, T.J.; Hewett, K.; Roth, M.S. Managing images in different cultures: A cross-national study of color meanings an preferences. J. Int. Mark. 2000, 8, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliff, M.A. Influence of wine glass shape on perceived aroma and colour intensity in wines. J. Wine Res. 2001, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delwiche, J.F.; Pelchat, M.L. Influence of glass shape on wine aroma. J. Sens. Stud. 2002, 17, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.; Zivanovic, S.; Morris, W.C.; Penfield, M.; Weiss, J. The effect of glass shape on the concentration of polyphenolic compounds and perception of Merlot wine. J. Food Qual. 2005, 28, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Vidal, P.; Cortés, S. Effect of the glass shape on flavor perception of “toasted wine” from Ribeiro (NW Spain). J. Sens. Stud. 2008, 23, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.H.; Yang, S.C. Investigation into the relationship between cup shape and the taste of tea. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Applied System Innovation, Sapporo, Japan, 13–17 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guéguen, N.; Jacob, C. Coffee cup color and evaluation of a beverage’s “warmth quality. Color Res. Appl. 2012, 39, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risso, P.; Maggiono, E.; Olivero, N.; Gallace, A. The association between the colour of a container and the liquid inside: An experimental study on consumers’ perception, expectations and choices regarding mineral water. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfer, K.; Ivens, B.; Brem, A. Multisensory innovation: Haptic input and its role in product design. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2017, 45, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.H.; Clifton, P.; Blumenthal, H.; Nandakumar, A.; Ganapathi, B.; Murray, J.; Mazalek, A. Universal Threshold Object: Designing Haptic Interaction for Televised Interactive Narratives. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Stanford, CA, USA, 15–19 January 2015; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.Z. Commercial Design; Artist Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, B.X. (Ed.) Fangming Spreads Far-Asian Tea Culture; National Palace Museum: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015.

- Mendel, J.M.; Korjani, M.M. Fast Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual Meeting of the North American Fuzzy Information Processing Society (NAFIPS), Berkeley, CA, USA, 6–8 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C.; Sedziaka, A. QCA and Fuzzy Set Applications to Social Movement Research. Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm482 (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- Zhang, Y.X. New Opportunities for the Reversal of Tribal Marketing in Food Design. Master’s Thesis, Department of Creative Life Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, P. Tutkiva toiminta ja ilmaisu, teos Tekeminen; Akatiimi oy: Hamina, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. Qualitative Comparative Analysis Using Fuzzy Sets (fsQCA). In Configurational Comparative Analysis; Rihoux, B., Ragin, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2008; pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, S.; Lettenmeier, M. Household-level transition methodology towards sustainable material footprints. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Professional Background | Sex | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Professional teacher of tea ceremony and ceramic designer | Male | 50 |

| 2 | Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 37 |

| 3 | Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 49 |

| 4 | Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 67 |

| 5 | Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 47 |

| 6 | Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 60 |

| 7 | Tea critic and Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 55 |

| 8 | Tea critic and Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 42 |

| 9 | Tea critic and Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Male | 57 |

| 10 | Tea merchant | Female | 40 |

| 11 | Tea merchant and Professional teacher of tea ceremony | Female | 42 |

| 12 | Tea maker and Tea critic | Male | 59 |

| Variable (Teacup) | Mean | Std. DEV | Minimum | Maximum | N Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.83333 | 1.404358 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| B | 2.666667 | 0.8498366 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| C | 3.25 | 0.9359664 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| D | 3.583333 | 1.320248 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| E | 4.333333 | 1.312335 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| Variable (Teacup) | Mean | Std. DEV | Minimum | Maximum | N Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.083333 | 1.114924 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| B | 2 | 0.9128709 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| C | 3.416667 | 1.114924 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| D | 3.666667 | 0.942809 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| E | 4 | 1.080123 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| Variable (Teacup) | Mean | Std. DEV | Minimum | Maximum | N Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.5 | 1.190238 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| B | 2.333333 | 1.027402 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| C | 2.75 | 1.163687 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| D | 4 | 0.7071068 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| E | 3.916667 | 1.114924 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| Variable (Teacup) | Mean | Std. DEV | Minimum | Maximum | N Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.666667 | 1.312335 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| B | 3.166667 | 1.067187 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| C | 2.666667 | 0.8498366 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| D | 2.916667 | 1.187317 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| E | 3.916667 | 1.320248 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| Variable (Teacup) | Mean | Std. DEV | Minimum | Maximum | N Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3.333333 | 1.490712 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| B | 3.416667 | 0.7592028 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

| C | 3.333333 | 1.178511 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| D | 3.333333 | 1.312335 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| E | 3.166667 | 1.621141 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| Variable (Teacup) | Mean | Std. DEV | Minimum | Maximum | N Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3.666667 | 1.027402 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

| B | 3.5 | 1.118034 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| C | 3.583333 | 0.9537936 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| D | 3.583333 | 0.9537936 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

| E | 4 | 1.080123 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| A Consistency/Coverage | B Consistency/Coverage | C Consistency/Coverage | D Consistency/Coverage | E Consistency/Coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taste of tea | |||||

| Preference of teacup | 0.863/0.593 | 1.00/0.724 | 0.952/0.571 | 0.954/0.552 | 0.952/0.425 |

| Bitterness of tea | |||||

| Preference of teacup | 0.818/0.782 | 0.904/0.826 | 0.952/0.555 | 0.954/0.525 | 0.952/0.465 |

| Astringency of tea | |||||

| Preference of teacup | 0.863/0.703 | 0.904/0.730 | 0.952/0.645 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.952/0.425 |

| Sweet aftertaste of tea | |||||

| Preference of teacup | 0.909/0.645 | 1.000/0.600 | 0.952/0.689 | 0.909/0.645 | 0.952/0.476 |

| Overall presentation of tea | |||||

| Preference of teacup | 0.863/0.542 | 1.000/0.552 | 0.952/0.555 | 0.909/0.571 | 0.904/0.558 |

| Overall Presentation of the Tea (Outcome) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Item | A Consistency/Coverage | B Consistency/Coverage | C Consistency/Coverage | D Consistency/Coverage | E Consistency/Coverage |

| Taste/Bitterness/Astringency/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.866/0.371 | 1.000/0.447 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Bitterness/Astringency/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.875/0.400 | 1.000/0.447 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.875/0.400 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness/Astringency/Sweet aftertaste | 0.866/0.371 | 1.000/0.447 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness/Astringency/Teacup preference | 0.875/0.400 | 1.000/0.447 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Taste/Astringency/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.866/0.371 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness/Sweet aftertaste | 0.875/0.400 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Taste/Astringency/Sweet aftertaste | 0.866/0.371 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Bitterness/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness/Astringency | 0.875/0.400 | 1.000/0.447 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.9000.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness/Teacup preference | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Bitterness/Astringency/Teacup preference | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.447 | 0.947/0.500 | 0.904/0.542 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Taste/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.950/0.558 |

| Taste/Astringency/Sweet aftertaste | 0.866/0.371 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.551 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Astringency/Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Taste/Astringency/Teacup preference | 0.866/0.371 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.528 | 0.952/0.571 | 0.947/0.529 |

| Bitterness/Sweet aftertaste | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.947/0.514 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Bitterness/Astringency | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.447 | 0.950/0.527 | 0.904/0.542 | 0.857/0.529 |

| Bitterness/Teacup preference | 0.889/0.457 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.950/0.527 | 0.904/0.542 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Taste/Bitterness | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Taste/Sweet aftertaste | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.583 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.904/0.558 |

| Astringency/Sweet aftertaste | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Sweet aftertaste/Teacup preference | 0.850/0.485 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.950/0.558 |

| Taste/Teacup preference | 0.894/0.485 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.583 | 0.952/0.571 | 0.950/0.558 |

| Taste/Astringency | 0.882/0.428 | 1.000/0.500 | 1.000/0.556 | 0.952/0.571 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Astringency/Teacup preference | 0.894/0.485 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.950/0.527 | 0.909/0.571 | 0.900/0.529 |

| Taste | 0.894/0.485 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.583 | 0.909/0.571 | 0.904/0.558 |

| Bitterness | 0.889/0.457 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.952/0.556 | 0.904/0.542 | 0.857/0.529 |

| Astringency | 0.894/0.485 | 1.000/0.500 | 0.952/0.556 | 0.909/0.571 | 0.857/0.529 |

| Sweet aftertaste | 0.850/0.485 | 1.000/0.553 | 1.000/0.583 | 0.95/0.542 | 0.904/0.558 |

| Preference of teacup | 0.863/0.542 | 1.000/0.553 | 0.952/0.556 | 0.909/0.571 | 0.904/0.558 |

| Variables of Tea | Variables of Teacup | F/Total | Pot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of tea taste | E cup (open mouth, deep belly) | 9/12 | 75 |

| Intensity of tea bitterness | E cup (open mouth, deep belly) | 4/12 | 33.3 |

| Intensity of tea sweet aftertaste | E cup (open mouth, deep belly) | 6/12 | 50 |

| Degree of preference of teacup | E cup (open mouth, deep belly) | 4/12 | 33.33 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.-C.; Peng, L.-H.; Hsu, L.-C. The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical Design of a Teacup. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246895

Yang S-C, Peng L-H, Hsu L-C. The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical Design of a Teacup. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246895

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Su-Chiu, Li-Hsun Peng, and Li-Chieh Hsu. 2019. "The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical Design of a Teacup" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246895

APA StyleYang, S.-C., Peng, L.-H., & Hsu, L.-C. (2019). The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical Design of a Teacup. Sustainability, 11(24), 6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246895