Abstract

Although emotional intelligence (EI) is positively associated with beneficial outcomes such as higher job performance and better psychological well-being, its relationship with creativity is uncertain. To assess an overall correlation between EI and creativity, in the present study a meta-analysis of 96 correlations obtained from 75 studies with a total sample size of 18,130 was conducted. The results uncovered a statistically significant moderate correlation (r = 0.32, 95% CI, 0.26–0.38, p < 0.01) between these two constructs. Moderation analyses revealed that the link was modulated by the type of EI/creativity measure and sample characteristics, such as gender, employment status, and culture. Specifically, the link was stronger when EI and creativity were measured using subjective reports (EI: trait EI; creativity: creative behavior and creative personality) compared to objective tests (EI: ability EI; creativity: divergent thinking test, remote associate test, and creative product). In addition, the link was stronger in males compared to females, in employees compared to students, and in East Asian samples compared to Western European and American samples. Theoretical implications and future directions are discussed in detail.

1. Introduction

Creativity is usually defined as the ability to generate and select ideas, solutions or products that are both novel and appropriate [1,2,3]. As a core means to supporting sustainable development, creativity is of vital importance for individuals and societies [4]. In addition to some well-known antecedents of creativity, such as fluid intelligence [5,6], openness to experience [7,8], and a supportive environment [9,10], the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and creativity has received increasing attention in recent years [11,12,13,14]. One widely accepted definition of EI is the ability to perceive, understand, use, and manage one’s own and others’ emotions [15], and it has also been identified as a positive predictor for health [16], academic performance [17], organizational leadership [18], and job performance [19]. However, findings on EI’s relationship with creativity are inconsistent.

Two theoretical explanations are proposed to explain the relationship between EI and creativity. The first is rooted in cognitive processing and regards EI and creativity as unrelated constructs that represent completely different cognitive abilities. Mayer, Roberts, and Barsade [20], for example, claimed that “EI also may exhibit relations with social intelligence, but apparently not with creativity” (pp. 519). The underlying logic to this argument is that EI reflects the ability to reach consensus and produce normative solutions to social and emotional situations, while creativity conversely reflects the ability to break from routines, think flexibly, and formulate unique ideas [21,22]. In line with this theoretic explanation, a number of studies have found null associations between EI and creativity [21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. For instance, Ivcevic, Brackett, and Mayer [21] examined the relationships between EI, creativity, and emotional creativity and, while they uncovered positive associations between emotional creativity and both self-reported and performance-based creativity measures, they did not find any significant associations between EI and creativity measures.

The second theoretical explanation emphasizes the affective links between EI and creativity. As revealed by Parke et al. [13] and Lea et al. [30], people with high EI are more competent in sustaining and using positive affect, a well-documented affective state that can stimulate creativity [31,32] through its effect of expanding the scope of idea generation [33] and fueling the persistence of idea exploration [34]. People with high EI are also more capable of channeling negative affect into change-oriented thinking processes—such as considering possible solutions to improve the dissatisfying situations—and, thus, generating creative solutions [35,36]. Consistent with these findings, several studies have reported positive correlations between EI and creativity in various samples, including students [37], salespeople [38], travel agents [39], and eldercare nurses [40].

From the above literature review, it is clear that the relationship between EI and creativity remains undetermined. It should be noted, however, that the relatively small numbers of participants in previous studies may limit the statistical power of their findings. To determine an overall relationship between EI and creativity, the present meta-analysis integrates all past studies for a much larger effective sample size. Moreover, the heterogeneous correlation coefficients across studies suggest that there may exist some systematic moderators in this relationship. Therefore, the present study further examines the moderating role of EI/creativity measures and participants’ demographic differences across studies by focusing on the following moderators: (a) the type of EI measure; (b) the type of creativity measure; and (c) the demographic profile of the sample (gender, employment status, and culture).

1.1. Emotional Intelligence Measure

EI measures typically used to examine the relationship between creativity and EI can be classified into two types: ability EI and trait EI [41,42]. Ability EI – such as the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) [43], emotional management ability test [27], and reading the mind in the eyes test [44], are usually conceptualized as people’s maximal performance in test situations of perceiving, appraising, using, and regulating emotions [20,42]. Trait EI—including the Bar-On emotional quotient inventory [45], trait emotional intelligence questionnaire [12], Schutte emotional intelligence scale [46], and Wong and Law’s emotional intelligence scale [47]—usually refers to individuals’ self-perception of emotion-related abilities, social skills, and personality [48,49].

Some studies have implied that EI measures may moderate the association between EI and creativity. Trait EI, for example, have been found to be positively associated with creativity in a variety of samples [37,38,39,40,50]. However, ability EI is rarely found to be associated with creativity (e.g., [13,21,27]).

1.2. Creativity Measure

Creativity measures typically used to examine the relationship between EI and creativity can be classified into five types [8,51,52,53]: (1) creative behavior (including the employee creativity scale [54]; Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale [55] and Creative Achievement Questionnaire [56]); (2) creative personality (e.g., Gough creative personality scale [57] and Williams Creativity Aptitude Test [58]); (3) divergent thinking test (such as the Alternative Uses Task [59] and Torrance Test of Creative Thinking [TTCT] [60]); (4) remote associate test [61]; and (5) creative product test (e.g., creative story task [62] and cartoon task [63]).

Some studies have implied that creativity measures may moderate the association between EI and creativity. For example, several studies uncovered moderate to large associations between EI and creative behavior and creative personality [39,64]. In contrast, the correlations between EI and divergent thinking test, remote associates test, and creative product are usually trivial [25,26].

1.3. Gender

Existing findings on gender differences in the relationship between EI and creativity are contradictory. Although some studies found high correlations between EI and creativity in samples mainly consisting of males [37,65], other studies found relatively low correlations between the constructs in majority-male samples [28,29]. Considering these inconsistencies in the findings, we cannot exclude the possibility that gender may moderate the relationship between EI and creativity.

1.4. Employment Status

The link between EI and creativity may differ based on participants’ employment status. A number of studies have reported moderate to large correlations among working adults [39,64], while others found small to moderate correlations in samples consisting mainly of students [21,27]. It is, therefore, possible that participants’ employment status may moderate the association between EI and creativity.

1.5. Culture

The association between EI and creativity may vary across cultures. For example, several studies conducted in East-Asian countries uncovered moderate to strong correlations between EI and creativity [14,37,39]. In contrast, however, studies conducted in Western Europe [26,29] and America [21,23] found relatively weak EI-creativity associations. Keeping these contradictory findings in mind, it is possible that culture may moderate the relationship between EI and creativity.

1.6. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to synthesize the results of previous studies that explored the relationship between EI and creativity, and to identify potential moderators that influence this relationship. Specifically, we aimed to (a) calculate an overall effect size for the relationship between EI and creativity and (b) explore whether the relationship between EI and creativity was influenced by EI/creativity measures and/or demographic variables (gender, employment status, and culture).

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

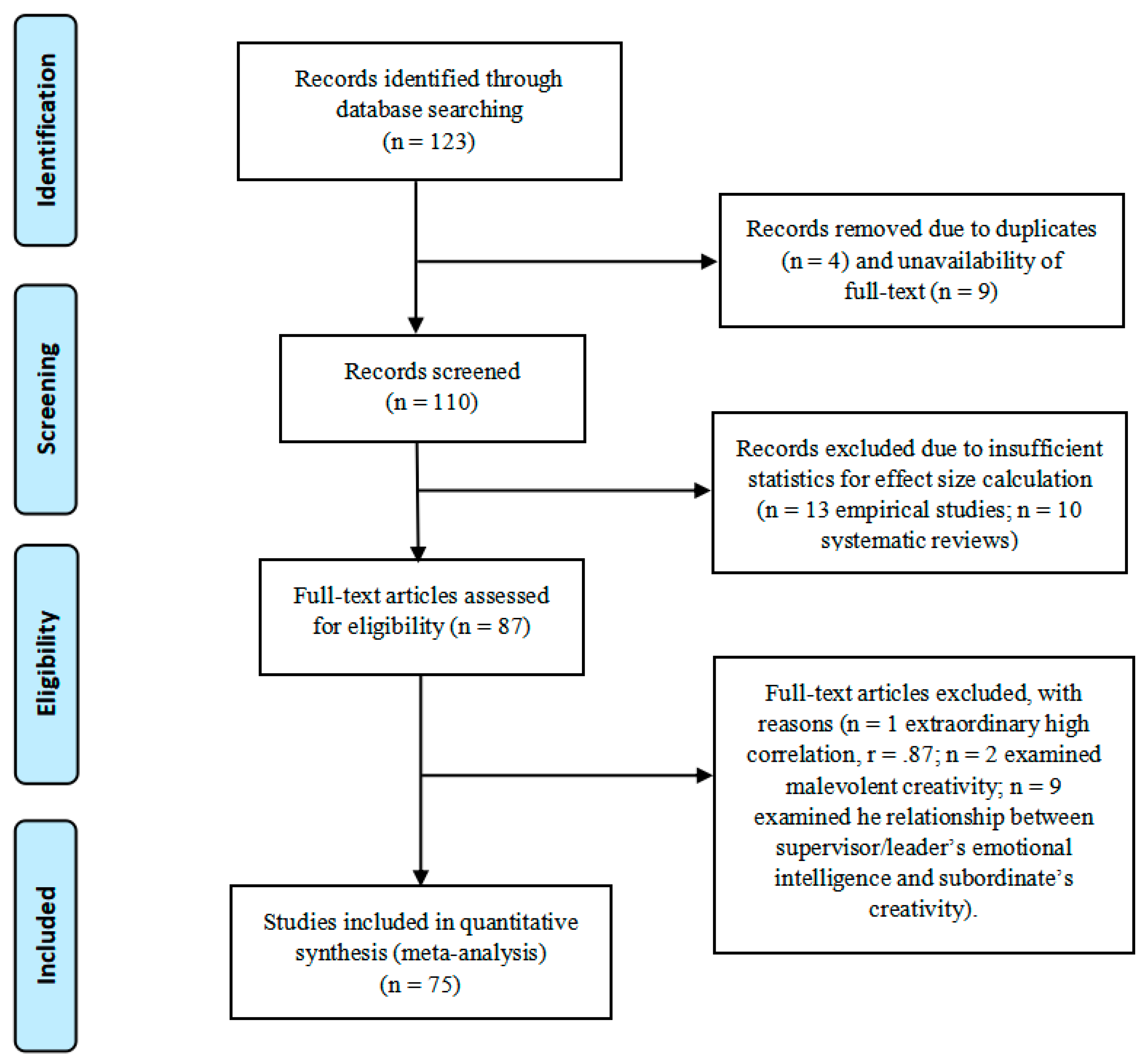

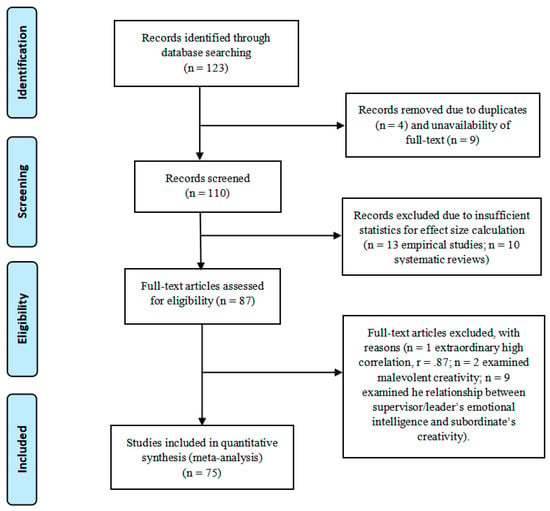

To locate studies on EI and creativity, we systematically searched literature published from January 1990 (when EI was first proposed by Salovey and Mayer [15]) to May 2019, using the following electronic databases: ProQuest Dissertations, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Springer, Taylor and Francis, EBSCO, and PsycINFO. Indexed keywords constituted terms reflecting EI (emotional intelligence, emotional ability, emotional competence, emotion recognition, emotion perception, emotion understanding, emotion appraisal, use of emotion, emotional regulation, emotional facilitation, and alexithymia—as a proxy of trait EI) and creativity (creativity, creative, divergent thinking, insight, innovative, innovation, innovator). The inclusion criteria for the articles were as follows: (a) studies the relationship between EI and creativity; (b) measures EI, represented by any of the keywords mentioned above; (c) measures creativity, represented by any of the keywords above; (d) explicitly reports the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r) or a t or F value that can be transformed to r; and (e) explicitly reports the sample size. Ultimately, we found 96 correlations obtained from 75 studies, with a combined sample size of 18130. As for the detailed literature selection process, please see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the literature selection process.

2.2. Coding

Studies were coded based on the following information: author(s) and publication year; r effect size; sample size; type of EI measure; type of creativity measure; proportion of males; employment status; and culture (Table 1). Correlations between different indicators of EI and creativity or between different indicators of creativity and EI were separately coded. If a study had several independent samples, we coded each separately.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis (N = 75).

There are five moderators in the present study: (a) EI measure, (b) creativity measure, (c) gender, (d) employment status, and (e) culture. The EI measure was coded as “trait EI” and “ability EI”. The creativity measure was coded as “creative behavior”, “creative personality”, “divergent thinking test”, “remote associate test”, and “creative product”. Gender was coded as the ratio of male participants. Employment status was coded as “employees”, “students”, and “mixed”. Culture was coded as “East Asian”, “Western European/American”, and “other”. For the purposes of this study, East Asia referred to Asian countries such as China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), South Korea, Philippines, and Singapore; Western European/American referred to European and North American countries, such as Germany, England, the United States of America, and Canada; and Other referred to countries outside of these geographic demarcations, such as Russia, Turkey, and Iran.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Meta-Analysis with Robust Variance Estimates

When a study provides multiple effect size estimates, a traditional approach is to aggregate the effect sizes drawn from the same study [118]. However, this method will eliminate the possibility of comparing multiple levels of a moderator within a single study. To overcome this limitation, we conducted our meta-analysis with robust variance estimates (RVE) [119], which can comprehensively analyze all the effect sizes and effectively accommodate the multiple sources of dependencies. When averaging the results of multiple studies, RVE provides two adjustment choices [119]: the correlated effects weighting scheme (where dependency primarily arises from studies providing multiple effect sizes for the outcome of interest) and the hierarchical effects weighting scheme (where dependency primarily arises from authors reporting multiple studies). In practice, both types of dependencies often exist in a meta-analysis, and it is recommended to select a weighting scheme based on the predominant type of dependency [120]. Of the 75 studies included in the current meta-analysis, only 5.33% (4) included multiple sub-studies, and 17.33% (13) provided multiple effect sizes. Therefore, we used the correlated effects weighting scheme to estimate our overall effect size and conduct moderator analyses.

Before calculating weights, a meta-analysis with RVE requires an estimate of the average correlation among dependent effect sizes within each study. The default assumed value is r = 0.80. We performed additional sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of this assumed value on our overall effect estimate (testing r = 0, 0.20, 0.40, 0.60, 0.80, 1.00). The results identified the robustness of effect sizes with different r estimations (testing r = 0, 0.20, 0.40, 0.60, 0.80, 1.00), so we only report analyses that used the default value of r = 0.80.

2.3.2. Testing Overall Effects and Moderators

To test the overall effect size, we fit an intercept-only random-effects meta-regression model with RVE using the R package, Robumeta [121]. The intercept of this model can be interpreted as the precision-weighted overall effect size, adjusted for correlated-effect dependencies. Following Borenstein et al.’s [118] recommendations, we converted the correlation coefficients to Fisher’s z during data analysis and then converted the results (e.g., summary effect and confidence intervals) back to correlation coefficients for ease of interpretation. We also used the RVE approach to perform separate hypothesis tests for the effects of each moderator. There was one continuous moderator (male ratio) and four categorical moderators (EI measure, creativity measure, employment status, and culture). Continuous moderators were entered into a meta-regression equation directly; the significance test corresponding to the regression coefficient for the predictor variable can be interpreted as a test of whether the variable is a significant moderator. Unlike the continuous moderators, categorical moderators were dummy-coded before being entered into meta-regression equations. To test whether there were significant differences across all levels of each categorical moderator, we conducted the Approximate Hotelling–Zhang test with small sample correction using the R package clubSandwich [122]. This test produces an F-value, an atypical degree of freedom, and a p-value that indicates the significance of moderating effect.

2.3.3. Testing Interactions between Moderators

In meta-analysis, moderators are often correlated [123]. In the present study, we employed two methods to examine the possible interactions between moderators. Firstly, we checked the bivariate associations of all moderators with SPSS 25 (IBM Corp, Released 2017; Armonk, NY, USA). We calculated Cramer’s V for a relationship between two categorical moderators (e.g., EI measure, creativity measure, employment status, and culture), and calculated the effect size partial η2 in case of a relationship between one categorical moderator and one continuous moderator (i.e., male ratio). According to Volker [124], interpretations of small = 0.01, medium = 0.06, and large = 0.14 were suggested for η2; and small = 0.10, medium = 0.29, and large = 0.45 were suggested for Cramer’s V. Moderate to large effect sizes would be indicative for confounding of moderators.

Secondly, we employed the R package Meta-CART [125] to identify possible interactions of significantly correlated moderators. This method used study effect sizes as outcome variables and potential moderators as predictor variables. The result of a Meta-CART analysis is a tree, and the end nodes of the tree are subgroups of studies with similar combinations of moderators. In each subgroup, a pooled effect size is computed (i.e., a weighted average effect size). The pooled effect sizes of these subgroups are as different as possible since Meta-CART maximizes the between-subgroup heterogeneity (i.e., Q between). Following Li et al.’s [125] suggestion, we applied random-effect weight and a pruning rule with c = 0.50 in Meta-CART analysis. Considering the relatively small number of studies (s = 75 < 80) in this meta-analysis, we only examined one two-way interaction each time.

2.3.4. Examining Publication Bias

Publication bias refers to the tendency of studies that report small or non-significant effects to be underrepresented in the published literature. Since publication bias analyses cannot be performed with RVE, we used the R package Mad [126] to aggregate dependent effect sizes with a prespecified correlation (r = 0.50) [118]. Then, we conducted the Orwin’s fail-safe N analysis [127] and the trim-and-fill analysis [128] with the R package metafor [129], based on the aggregated 75 effect sizes (one effect size per study). Orwin’s fail-safe N indicates how many studies with null results (r = 0) would have to be added to reduce the present average effect size to a trivial level. Trim-and-fill analysis indicates how many missing studies are needed to make the funnel plot symmetrical.

3. Results

A total of 75 studies and 96 effect sizes were analyzed in the current study. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the analyzed studies.

3.1. Overall Effect

Using meta-regression with RVE, the overall model with 96 indicators provided an estimated effect size of r = 0.32 (95% CI, 0.26–0.38, p < 0.01). This indicates that EI generally exhibited a moderately strong, positive relationship with creativity. In order to test the robustness of our findings, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which the above analysis was repeated while excluding studies with r > 0.70. Although the overall point estimate for the remaining 92 indicators dropped, it was still significant (r = 0.29, 95% CI, 0.24–0.34, p < 0.01), showing that the moderate positive relationship between EI and creativity is robust.

3.2. Moderator Analysis

The effect sizes were very heterogeneous (T2 = 0.06, I2 = 93.45). Such heterogeneity suggests that there may be meaningful differences among studies that can be further explored through moderator analyses. Table 2 contains effect size estimates for each level of each moderator and the accompanying moderator analyses.

Table 2.

Moderator analyses.

3.2.1. The Influence of the EI Measure

As shown in Table 2, the measures of EI significantly moderated the relationship between EI and creativity, with F (1, 11.40) = 22.70, and p < 0.01. Specifically, this correlation is stronger when EI is conceptualized as trait EI (r = 0.35, 95% CI, 0.29–0.41, p < 0.01) than as ability EI (r = 0.08, 95% CI, –0.01–0.18, p = 0.12).

3.2.2. The Influence of the Creativity Measure

As shown in Table 2, the measure of creativity significantly moderated the relationship between EI and creativity, F (4, 1.70) = 17.10, p < 0.01. Specifically, the correlation is much stronger when creativity is measured as creative behavior (r = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.32–0.45, p < 0.01) and creative personality (r = 0.33, 95% CI, 0.20–0.46, p < 0.01) than as divergent thinking (r = 0.07, 95% CI, 0.00–0.12, p = 0.03), convergent thinking (r = 0.11, 95% CI, –0.14–0.36, p = 0.56), and creative product (r = 0.03, 95% CI, –0.08–0.15, p = 0.58). However, this result should be interpreted with caution due to the small degree of freedom (df = 1.70 < 4). This may be a result of the asymmetrical distribution of indicator numbers for different creativity measures. For example, there are 49 indicators for creative behavior, while only two indicators for RAT.

3.2.3. The Influence of Gender

The percentage of males in the full dataset is 50.10%. To examine whether gender moderated the link between EI and creativity, r was meta-regressed onto the percentage of males in 64 studies (84 indicators) that reported information regarding participants’ gender distribution. As shown in Table 3, the results suggested that the effect sizes of correlation were marginally and positively predicted by the ratio of males (β = 0.32, 95% CI, –0.02–0.67, p = 0.07). This indicates that the relationship between EI and creativity is stronger in males than in females.

Table 3.

Meta-regression analysis of continuous moderator variables (random-effect model).

3.2.4. The Influence of Employment Status

As shown in Table 2, the participants’ employment status did not moderate the relationship between EI and creativity in general, F (2, 2.52) = 2.21, p = 0.28. However, we should interpret this finding with caution due to the small degree of freedom (df = 2.52 < 4). In fact, further analysis indicated that, while excluding the mixed samples (k = 7), the EI-creativity association was significantly stronger in employees (r = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.31–0.46, p < 0.01) than in students (r = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.15–0.33, p < 0.01), F (1, 64.6) = 6.19, p = 0.02.

3.2.5. The Influence of Culture

As shown in Table 2, the magnitude of correlation coefficients between EI and creativity are significantly different among the three culture classifications (East Asian, Western European/American, and other), F (2, 11.4) = 9.06, p < 0.01. Specifically, this correlation was higher in East Asian samples (r = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.37–0.60, p < 0.01) and in other samples (r = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.29–0.44, p < 0.01) than in Western European/American samples (r = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.09–0.26, p < 0.01).

3.3. Bivariate Associations and Synergistic Effects between Moderators

As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, there existed five significant associations and one marginally significant association between moderators: EI measure and creativity measure (Cramer’s V = 0.43, p < 0.01 ), EI measure and culture (Cramer’s V = 0.50, p < 0.01 ), creativity measure and employment status (Cramer’s V = 0.28, p = 0.05), creativity measure and culture (Cramer’s V = 0.29, p = 0.04), male ratio and employment status (partial η2 = 0.20, p < 0.01 ), and male ratio and culture (partial η2 = 0.17, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

The effect size (Cramer’s V) for the relationships among categorical moderators.

Table 5.

The effect size (partial η2) for the relationships between male ratio and categorical moderators.

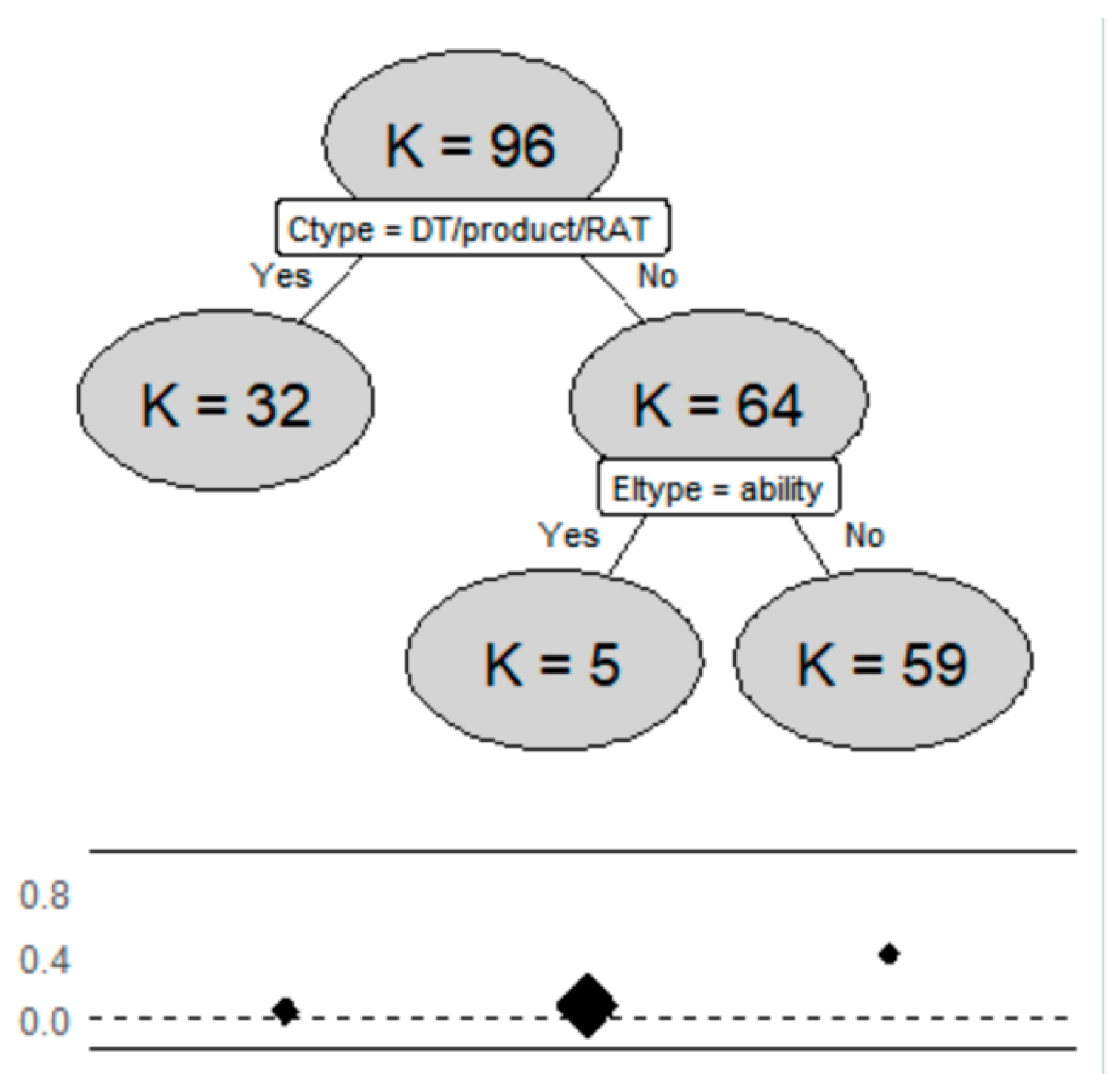

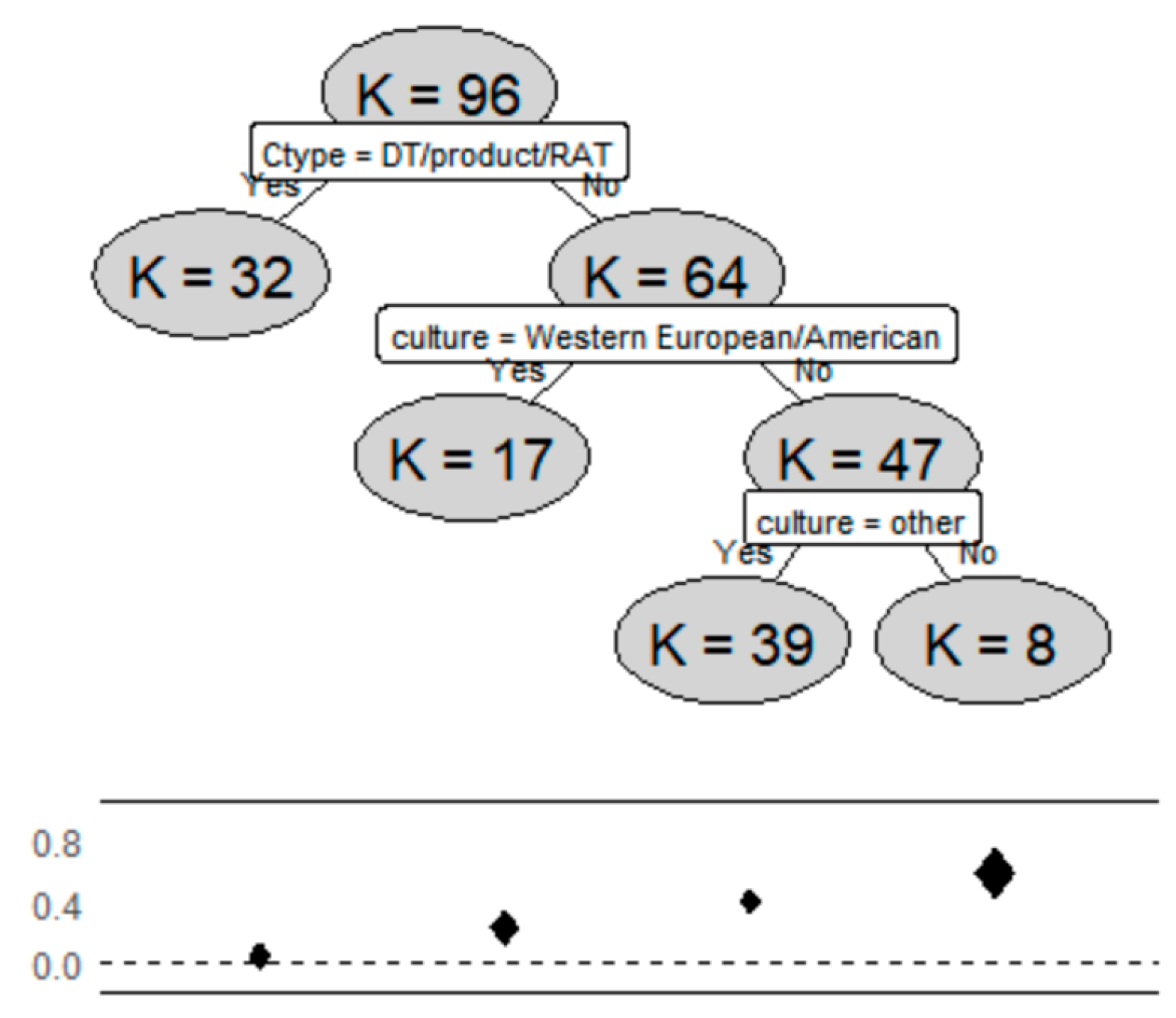

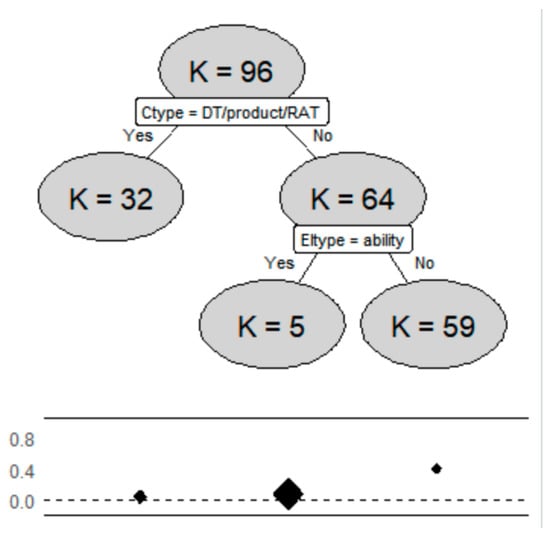

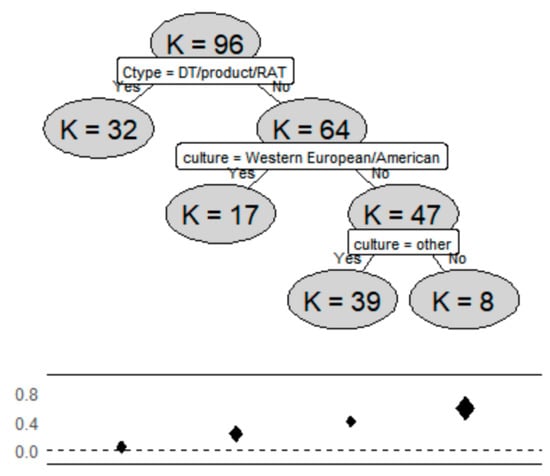

In addition, the results of the Meta-CART analysis further identified two synergistic effects among these six associates: EI measure and creativity measure (Q between (2) = 52.97, p < 0.01), as well as the creativity measure and culture (Q between (3) = 59.47, p < 0.01). As shown in Figure 2, the correlations between trait EI and subjective reports of creativity (including creative behavior and creative personality) (r = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.34–0.43, p < 0.01) were much higher than those between ability EI and subjective reports of creativity (r = 0.09, 95% CI = –0.10–0.28, p = 0.40), and also much higher than those between EI (including both ability and trait) and objective tests of creativity (i.e., divergent thinking, remote associate test, creative product) (r = 0.05, 95% CI = –0.03–0.13, p = 0.21). As shown in Figure 3, the correlation between EI and subjective reports of creativity was highest in the East Asian sample (r = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.42–0.64, p < 0.01), followed by the Other sample (r = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.32–0.44, p < 0.01) and the Western European/American sample (r = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.13–0.33, p < 0.01). In contrast, the correlation between EI and objective tests of creativity was the lowest (r = 0.05, 95% CI = –0.03–0.13, p = 0.21), regardless of the sample’s cultural characteristics. Specifically, in East Asian countries (k = 2), this correlation is r = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.01–0.38, p = 0.30; in Western European and American countries (k = 21), this correlation is r = 0.05, 95% CI = −0.00–0.11, p = 0.13; in other countries (k = 9), this correlation is r = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.00–0.17, p = 0.11; F (2, 0.49) = 0.39, p = 0.79.

Figure 2.

Result of the random Meta-CART analysis with the EI measure and creativity measure as predictor variables.

Figure 3.

Result of the random Meta-CART analysis with the creativity measure and culture as predictor variables.

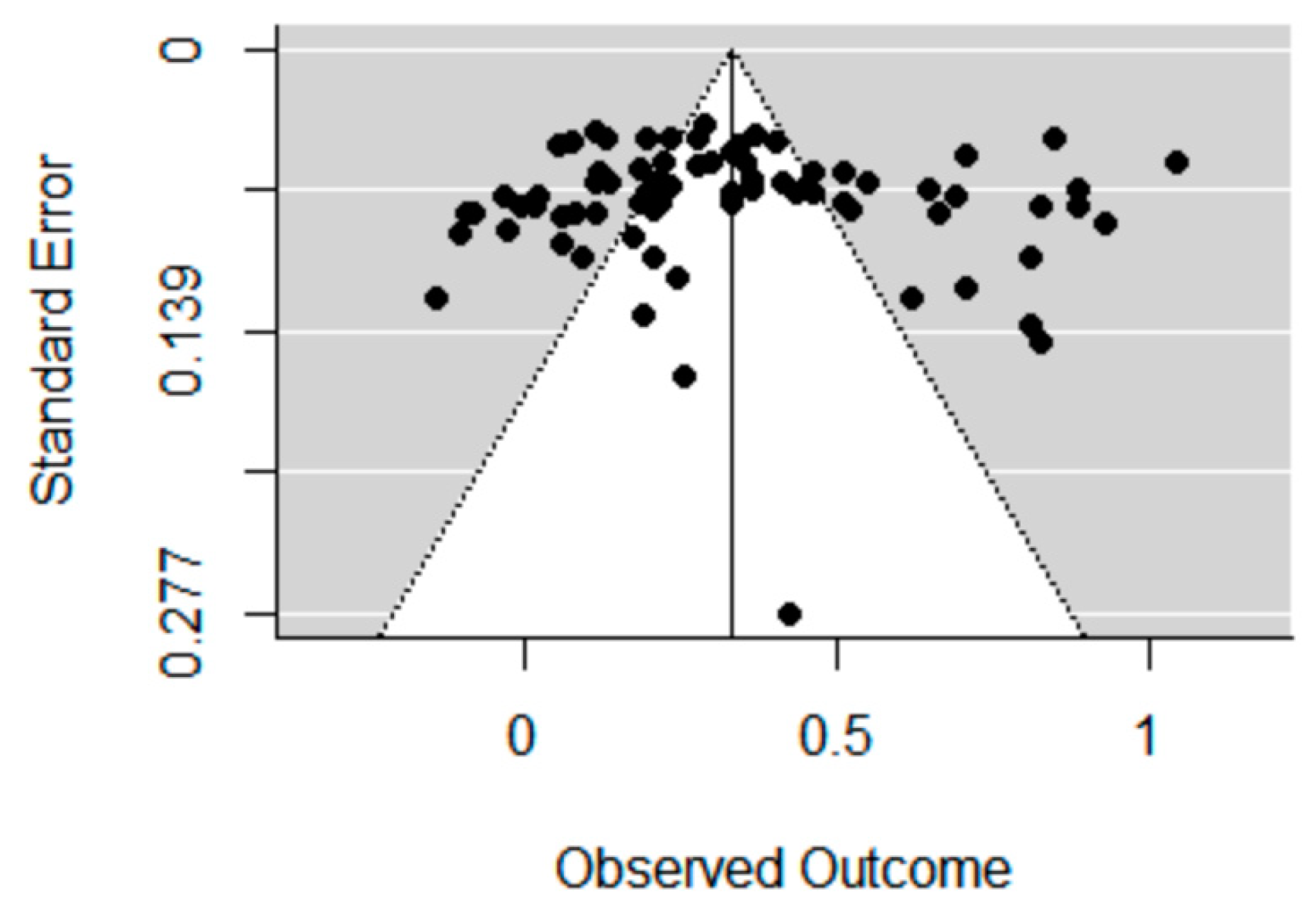

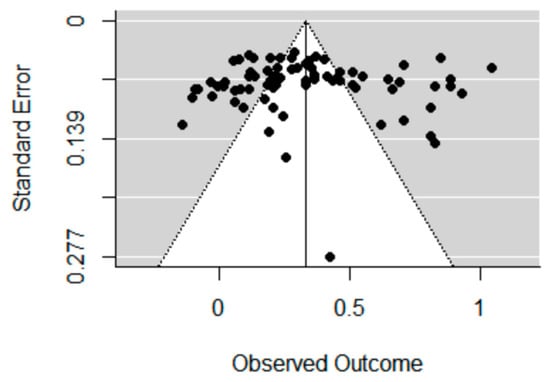

3.4. Publication Bias

The results of Orwin’s fail-safe N analysis indicated that, if we adopted Hyde and Linn’s [130] value of 0.10 as a trivial effect size, it would take 175 studies with effect sizes of 0 that we overlooked to reduce our results to trivial. The results of the trim-and-fill showed a symmetric funnel plot and, thus, there was no need to add additional studies (Figure 4). Overall, publication bias probably does not play a significant role in the present meta-analysis.

Figure 4.

A funnel plot of the trim-and-fill analysis indicates no need for additional studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. General Relationship between EI and Creativity

Our results uncover that, in general, EI was moderately and positively associated with creativity (r = 0.32), thus supporting the view that EI can be related to creativity through affective links [13]. This may because people with high EI are more capable of engaging and maintaining positive affect and channeling negative affect into more constructive directions [13,35]. On the one hand, as emphasized by Parke et al. [13], the state of “high energy, full concentration, and pleasurable engagement” triggered by positive affect [131] can stimulate individuals to explore problems more flexibly and sustain their exploration more persistently. Emotionally intelligent people are also better able to channel negative affect into finding alternative solutions to improve rather than complain about the dissatisfying solutions [35,36]. Overall, people with high EI can utilize their positive affect and negative affect more effectively to facilitate thinking and reasoning, which, in turn, leads to a higher possibility of creative outputs [12,132].

4.2. Moderating Role of EI Measures

The measure of EI moderates the positive correlation between EI and creativity. In line with previous meta-analyses that revealed higher EI-Health correlations when EI is measured as a trait than as an ability [133], the present study also uncovered similar findings in the context of the EI-creativity correlation. One possible explanation for this difference may result from the “common method bias” [134]. As most of the studies included in the present meta-analysis employed subjective reports of EI (83.30%) and creativity (66.67%), the correlation between these two constructs may be larger than actual levels due to similar response dispositions. Another possible explanation is that ability EI may be too narrow to be comprehensive. For example, an objective test of ability EI—Reading the Mind in the Eyes [77]—only taps a specific component (i.e., recognize emotions) of ability EI. Similarly, the MSCEIT—another objective test of ability EI [13,21]—was also argued to have low predictive validity [135,136,137]. Based on these findings, it is not surprising to find a stronger relationship when EI was measured as a trait.

4.3. Moderating Role of Creativity Measures

Creativity measures moderate the positive relationship between EI and creativity. In line with Tu et al.’s [14] empirical findings, this relationship is larger when creativity is measured by subjective reports (including creative behavior and creative personality) than by objective tests (including divergent thinking test, remote associate test, and creative product). It should be noted that several studies included in the meta-analysis simultaneously employing subjective reports and objective tests as indicators of creativity, revealed similar findings to our moderator analysis [14,26,68,114]. For example, Tu et al. [14] found a stronger EI-creativity correlation when creativity was measured by creative behavior (the Kaufman domains of creativity scale, r = 0.47) and a weaker correlation when creativity was measured by divergent thinking test (the Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults, r = 0.09). Same as with EI measures, this correlation pattern may result from the common method bias [134], given that most of the measures of EI (83.30%) and creativity (66.67%) were based on subjective reports. In addition, although people with high EI tend to be more competent in finding creative ways to solve real-life problems [138], they are not necessarily good at solving objective creativity tests. For example, Beaty, Nusbaum, and Silvia [139] found that individuals’ engagement in creative activities was not related to their insight problem-solving performance. Therefore, the relatively weak associations between objective measures of creativity and EI (i.e., r = 0.07 for divergent thinking test, r = 0.11 for the remote associate test, and r = 0.03 for creative product) are to be expected.

4.4. Synergistic Effect between EI Measures and Creativity Measures

To our knowledge, the present meta-analysis is the first to find that the EI measures and creativity measures can collectively moderate the EI-creativity association. Specifically, when creativity was measured by objective tests (including divergent thinking test, remote associate test, and creative product), there were no significant differences in the strength of the EI-creativity association whether EI was measured as an ability (r = 0.05) or as a trait (r = 0.08). However, when creativity was measured by subjective reports (including creative behavior and creative personality), the strength of the EI-creativity association was much stronger when EI was measured as a trait (r = 0.39) compared to as an ability (r = 0.09).

These findings indicate that the relationship between EI and creativity is quite complicated. Therefore, the generally positive EI-creativity correlation (r = 0.32) should be interpreted with caution. In fact, this moderate association only emerges when both EI and creativity are measured by subjective-report instruments. In cases when either EI or creativity is measured by objective performance tests, the EI-creativity correlation decreased sharply to a non-significant level. For instance, Ivcevic et al. [21] revealed that an individual’s ability EI performance was neither associated with their creative activity scores nor associated to their divergent thinking (i.e., consequences task) and RAT scores. In another study, Zenasni et al. [22] found that participants’ performance in an objective test of creativity (i.e., create an advertisement to reduce the aggressive behaviors of drivers) was neither related to their ability EI scores (i.e., emotion perception) nor related to their trait EI scores (i.e., alexithymia). Based on these findings, it seems reasonable to conclude that ability EI (that involves normative reactions and social consensus) and performance-based creativity (that calls for non-normative solutions) can be regarded as two cognitively unrelated constructs [20,21,22]. In the future, researchers should pay more attention to the low predictive validity of some objective tests of ability EI [135,136,137] and creativity [139].

4.5. Moderating Role of Gender

Gender moderates the positive correlation between EI and creativity. Specifically, this correlation is larger among males than among females. While previous studies had mixed results on whether EI differs significantly between males and females [140,141], there is some evidence that males are more competent in emotion regulation, while females are more capable of recognizing and expressing emotions [142,143,144]. According to Parke et al. [13], people with strong emotion regulation and facilitation abilities can more effectively maintain and use positive affect to stimulate creativity. In contrast, people with high emotion recognition ability may be more vulnerable to external emotional stimuli, making it difficult to sustain deep idea exploration. Based on these assumptions, it seems reasonable that EI relates to creativity more strongly in males than in females.

4.6. Moderating Role of Employment Status

Participants’ employment status moderates the positive correlation between EI and creativity. Specifically, this correlation is larger among employees than students. This could possibly be explained by the different levels of emotional labor demand of these two populations. As revealed by Joseph and Newman [145], the relationship between EI and job performance is much stronger in jobs with high emotional labor demands than those with lower demands. With regard to our findings, the workplace involves much more interpersonal interaction and emotion regulation processes than schools. For example, it is common for employees from different functional areas to collaborate on projects and, in the process of putting creative ideas into practice, employees need not only high levels of general intelligence to ensure the quality of implementation, they also need high levels of EI to sustain team cohesion and concentrate all available resources on the group’s creative efforts [36]. Barczak et al. [67] found that team EI could enhance team creativity by promoting team trust and developing a collaborative culture in the team. In contrast, compared to employees working in the real commercial world, especially those working in service industry (e.g., airline hostesses), emotional labor is much less demanding in students, given that they “are not directed to present specific emotion displays and are not rewarded or penalized for the displays” [146]. Therefore, it is not surprising that EI is more strongly related to creativity in employees than in students.

4.7. Moderating Role of Culture

Culture moderates the positive correlation between EI and creativity. Specifically, when creativity is measured by subjective reports (e.g., creative behavior and creative personality), this correlation is larger in studies conducted in East Asian cultures than in Western European and American cultures. This result is consistent with Zhang’s [147] study, which showed a stronger correlation between individual emotional intelligence and workplace performance in the Chinese cultural context than in Western cultural contexts. The reason underlying these cultural differences may result from the collectivist cultures of East Asian countries, compared to the individualistic cultures of Western European and American cultures [148]. In a collectivist culture, highly unique ideas tend to be perceived as deviant [149] and are subject to others’ disapproval [150]. Compared to those with low EI, people with high EI are better at choosing appropriate time and strategies to communicate their unique ideas to others [36] and, thus, are more likely to get external support to put their creative ideas into practice. In contrast, individualist culture tends to encourage individuals to freely express their own internal thoughts, feelings, and actions [150], which means people can devote themselves to improve the originality of their ideas or products. No matter how high or low their EI is, people in Western Europe and the Americas have a good chance to obtain necessary financial and policy support as long as their ideas or products are truly creative. Therefore, it is reasonable that creativity relies more heavily on EI in East Asian cultures than in Western European and American cultures.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

It is necessary to consider a number of limitations when interpreting the results of this meta-analysis. First, all the studies included in the present meta-analysis are cross-sectional and cannot establish a causal relationship between EI and creativity. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to further establish the direction(s) of causality for the relationship between EI and creativity. Second, although we found moderate correlations between EI and creativity, the motivational, cognitive, and affective processes through which EI stimulates creative performance is still unclear, and future studies that deeply explore how EI affects creativity are warranted. Third, in the database of our meta-analysis, only one study [14] explicitly examined the relationship between EI and domain-specific creativity. Considering the domain-specific nature of creativity, it would be valuable to further explore the role of EI in various creativity domains (e.g., science, technology, and arts) with more ecological research designs. Fourth, the large heterogeneity across effect sizes (T2 = 0.06, I2 = 93.45) indicates to us that there may exist some relatively poor-quality studies (e.g., unstandardized measures, inadequate reliability and validity checks, possible common method bias, and few controlled variables) in our meta-analysis database, which would further constrain the validity of our findings. To overcome this limitation in the future, researchers are encouraged to take stricter strategies to ensure the quality of research (e.g., employing well-established instruments and engaging in preregistration of research designs).

6. Conclusions and Implications

To summarize, the present meta-analysis revealed a moderately positive correlation between EI and creativity. Furthermore, the EI and creativity measures, gender, participants’ employment status, and culture all moderated this correlation. Specifically, the link was stronger when EI and creativity were measured by subjective reports than by objective tests among males, among employees and in East Asian samples. These findings have some practical implications for stakeholders, such as employers and educators. For example, intervention programs aiming to increase employee’s or students’ creativity should also take EI into consideration, although this may pose additional challenges to service providers. Moreover, more attention should be paid to male employees in East Asian culture, given that the link between EI and creativity is strongest in these samples. Doing so would largely stimulate the individuals’ creative potential and promote sustainable development for organizations and societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: X.X. and W.P.; formal analysis: X.X. and W.L.; software: X.X.; writing—original draft preparation: X.X. and W.L.; writing—review and editing: X.X. and W.P.

Funding

This research was conducted with the financial support from Shanghai “Li De Shu Ren” Humanities and Social Sciences Key Research Base (Psychology) (13200-412224-18093) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019ECNU-HWFW022).

Acknowledgments

We thank Hao Lei and Chao Yan for their warm-hearted suggestions in data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Runco, M.A. Commentary: Divergent thinking is not synonymous with creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2008, 2, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A.; Acar, S. Divergent thinking as an indicator of creative potential. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Lubart, T.I. The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms. In Handbook of Creativity; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Creativity and organizational learning as means to foster sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M.; Furnham, A.; Saffiulina, X. Intelligence, general knowledge and personality as predictors of creativity. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2010, 20, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J. Intelligence and creativity are pretty similar after all. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.S.; Silvia, P.J. Creative days: A daily diary study of emotion, personality, and everyday creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberg, J.; Reiter-Palmon, R. Creativity and the Big Five Personality Traits: Is the Elationship Dependent on the Creativity Measure? In the Cambridge Handbook of Creativity and Personality Research; Feist, G.J., Reiter-Palmon, R., Kaufman, J.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.G.; Sugioka, H.L.; Yamagata-Lynch, L.C. Supportive classroom environments for creativity in higher education. J. Creat. Behav. 1999, 33, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.; Mishra, P. Learning environments that support student creativity: Developing the SCALE. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 27, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Z.; Brackett, M.A. Predicting creativity: Interactive effects of openness to experience and emotion regulation ability. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, M.H. Moderating role of job autonomy and supervisor support in trait emotional intelligence and employee creativity. Vision 2018, 22, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, M.R.; Seo, M.G.; Sherf, E.N. Regulating and facilitating: The role of emotional intelligence in maintaining and using positive affect for creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, C.; Guo, J.; Hatcher, R.C.; Kaufman, J.C. The relationship between emotional intelligence and domain-specific and domain general creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Bhullar, N.; Rooke, S.E. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, F.; Cain, J.; Smith, K.M. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of academic and/or professional success. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2006, 70, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B.; Walls, M.; Burgess, Z.; Stough, C. Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2001, 22, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.; Huang, G.H.; Li, X. The effects of emotional intelligence on job performance and life satisfaction for the research and development scientists in China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2008, 25, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Roberts, R.D.; Barsade, S.G. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 5, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Z.; Brackett, M.A.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence and emotional creativity. J. Pers. 2007, 75, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenasni, F.; Lubart, T.I. Perception of emotion, alexithymia and creative potential. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastello, S.J.; Guastello, D.D.; Hanson, C.A. Creativity, mood disorders, and emotional intelligence. J. Creat. Behav. 2004, 38, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. Creative thinking of high school students in relation to their emotional intelligence. J. Psychol. 2015, 2, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova, E.M.; Kornilova, T.V. Creativity and tolerance for uncertainty predict the engagement of emotional intelligence in personal decision making. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2013, 6, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Hernandez-Torrano, D.; Perez-Gonzalez, J.; Batey, M.; Petrides, K. The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and creativity across subject domains. Motiv. Emot. 2011, 35, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.C.; Pribil, A.; Wallner, A.; Hofer, G. The self-other knowledge asymmetry in cognitive intelligence, emotional intelligence, and creativity. Heliyon 2018, 4, e01061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Scandura, T.; Kim, Y.; Joshi, K.; Lee, J. Examining leader-member exchange as a moderator of the relationship between emotional intelligence and creativity of software developers. Eng. Manag. Res. 2012, 1, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. The relationship between cognitive ability, emotional intelligence and creativity. Psychology 2016, 7, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, R.G.; Qualter, P.; Davis, S.K.; Pérez-González, J.C.; Bangee, M. Trait emotional intelligence and attentional bias for positive emotion: An eye tracking study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 128, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, M.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A. A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 779–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, B.A.; Amabile, T. Creativity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Barsade, S.G.; Mueller, J.S.; Staw, B.M. Affect and creativity at work. ADM Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 367–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. Awakening employee creativity: The role of leader emotional intelligence. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W. Self-perceived creativity, family hardiness, and emotional intelligence of Chinese gifted students in Hong Kong. J. Adv. Acad. 2005, 16, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassk, F.G.; Shepherd, C.D. Exploring the relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and salesperson creativity. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2013, 33, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.; Lee, Y.J. Emotional intelligence and employee creativity in travel agencies. Curr. Issues Tour 2014, 17, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, H.; Mauno, S. Associations of trait emotional intelligence with social support, work engagement, and creativity in Japanese eldercare nurses. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2017, 59, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchard, K.A.; Brackett, M.A.; Mestre, J.M. Taking stock and moving forward: 25 years of emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.J.; Hill, A.; Kaya, M.; Martin, B. The Measurement of Emotional Intelligence: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommendations for Researchers and Practitioners. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT): User’s Manual; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The ‘reading the mind in the eyes’ test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psyc. 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): A Test of Emotional Intelligence; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M.; Hall, L.E.; Haggerty, D.J.; Cooper, J.T.; Golden, C.J.; Dornheim, L. Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Mikolajczak, M.; Mavroveli, S.; Sanchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Furnham, A.; Pérez-González, J.C. Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.C.; Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. Measuring Trait Emotional Intelligence. In Emotional Intelligence: An International Handbook; Schulze, R., Roberts, R.D., Eds.; Hogrefe & Huber: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; McKay, A.S.; Kaufman, J.C. Emotional intelligence and creativity: The mediating role of generosity and vigor. J. Creat. Behav. 2014, 48, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M. The measurement of creativity: From definitional consensus to the introduction of a new heuristic framework. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.C.; Beghetto, R.A. Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Beghetto, R.A. Creative behavior as agentic action. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 682–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.C. Counting the muses: Development of the Kaufman domains of creativity scale (K-DOCS). Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.; Peterson, J.B.; Higgins, D.M. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the creative achievement questionnaire. Creat. Res. J. 2005, 17, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, H.G. A creative personality scale for the Adjective Check List. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.E. Creativity Assessment Packet (CAP): Manual; DOK: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Guilford, J.P. The Nature of Human Intelligence; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, E.P. The Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking-Norms-Technical Manual Research Edition-Verbal Tests, Forms A and B-Figural Tests, Forms A and B; Personnel Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mednick, S.A. The associative basis of the creative process. Psychol. Rev. 1962, 3, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornilov, S.A.; Grigorenko, E.L. An assessment battery for analytical, creative, and practical abilities. Psychol. J. 2010, 31, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- The Rainbow Project Collaborators. The rainbow project: Enhancing the SAT through assessments of analytical, practical, and creative skills. Intelligence 2006, 34, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Coelho, A. The impact of emotional intelligence on creativity, the mediating role of worker attitudes and the moderating effects of individual success. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 25, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Rahman, M.S. Assessing the relationship among emotional intelligence, creativity and empowering leadership: An empirical study. J Bus. 2016, 37, 198–215. [Google Scholar]

- Aritzeta, A. Emotional Intelligence and Innovation: An Exploratory Study in Organizational Settings. In Behavior and Organizational Change; Ayestaran, S., Goenaga, J.B., Eds.; Center for Basque Studies: Reno, NV, USA, 2011; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Barczak, G.; Lassk, F.; Mulki, J. Antecedents of team creativity: An examination of team emotional intelligence, team trust and collaborative culture. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2010, 19, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, S. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Work Engagement, Creativity and Demographic Variables. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Czernecka, K.; Szymura, B. Alexithymia-imagination-creativity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L.; De Vita, G. Emotional intelligence and creative performance: Looking through the lens of environmental uncertainty and cultural intelligence. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.M. The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and experienced ESL/EFL teachers’ love of English, attitudes towards their students and institution, self-reported classroom practices, enjoyment and creativity. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 41, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, H.; Gencer, G.; Orhan, N.; Sahinbas, K. The significance of emotional intelligence on the innovative work behavior of managers as strategic decision-makers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dincer, H.; Orhan, N. Relationship between emotional intelligence and innovative work behaviors in Turkish banking sector. Int. J. Financ. Bank. Stud. 2012, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, B.; Gocen, G.; Yakar, A. The examination of relationships between emotional intelligence levels and creativity levels of pre-service teachers in the teaching-learning process and environments. J. Educ. Instr. 2014, 42, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.R.; Heydarnejad, T.; Najjari, H. The interplay among emotions, creativity and emotional intelligence: A case of Iranian ELF teachers. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Transl. Stud. 2018, 6, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G.L.; Kumar, V.K.; Porter, J. Emotional creativity, alexithymia, and styles of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2007, 19, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geher, G.; Betancourt, K.; Jewell, O. The link between emotional intelligence and creativity. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 2017, 37, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheydar, Z.; Amiri, B.M. The Relationship among EFL Learners’ Creativity, Emotional Intelligence, and Self-Efficacy. In Linguistics, Culture and Identity in Foreign Language Education; Akbarov, A., Ed.; International Burch University: Sarajevo, Herzegovina, 2014; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, K.; Lim, K.Y. Perceived creativity: The role of emotional intelligence and knowledge sharing behavior. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 13, 1450037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozukara, E. Beyond the expected activities: The role of impulsivity between emotional intelligence and employee creativity. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, G.; Kocevar, U.; Krvina, K.; Pureber, P.; Aleksic, D. Sparking student creativity: Examining the relationship between knowledge sharing, emotional intelligence, intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and creativity. Dyn. Relatsh. Manag. J. 2016, 5, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Bajaj, B. Positive affect as mediator between emotional intelligence and creativity: An empirical study from India. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health Hum. Resil. 2017, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Mao, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhuang, K.; Zhu, X.; Qiu, J.; Chen, X. Examining brain structures associated with emotional intelligence and the mediated effect on trait creativity in young adults. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.; Russ, S. Pretend play, creativity, and emotion regulation in Children. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, W.; Yuan, Q. Frontline disruptive leadership and new generation employees’ innovative behaviour in China: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2018, 24, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, M.H.; Dem, C.; Choden, S. Emotional intelligence and employee creativity: Moderating role of proactive personality and organizational climate. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2016, 4, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanian, R. The relationship between students’ creativity and emotional intelligence in technical and vocational colleges. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2012, 11, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalian, A.; Yaghoubi, N.; Poori, M. Emotional intelligence and corporate entrepreneurship: An empirical study. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2011, 1, 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, S.; Zubair, A. Emotional intelligence self-efficacy, and creativity among employees of advertising agencies. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2014, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mall-Amiri, B.; Fekrazad, A.A. The Relationship among Iranian EFL learners’ creativity, emotional intelligence, and language learning strategies. J. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2015, 5, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, K. Job stress and employee creativity: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Int. J. Manag. Excell. 2017, 9, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ngah, R.; Ismail, W.; Tajuddin, A.; Emrie, H. Emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial intention: Impact of creativity. Proc. ASEAN Entrep. Conf. 2012, 200, 200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ngah, R.; Salleh, Z. Emotional intelligence and entrepreneurs’ innovativeness towards entrepreneurial success: A preliminary study. Am. J. Econ. 2015, 5, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.N.; Takahashi, Y.; Nham, T. Challenge stressors and creativity: Moderating effect of emotional intelligence. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2018, 1, 13774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorafshan, L.; Jowkar, B. The effect of emotional intelligence and its components on creativity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 84, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nori, R.; Signore, S.; Bonifacci, P. Creativity style and achievements: An investigation on the role of emotional competence, individual differences, and psychometric intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatoye, R.A.; Akintunde, S.O.; Yakasai, M.I. Emotional intelligence, creativity and academic achievement of business administration students. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 8, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuigwe, N.E.; Ezeani, C.; Anyaoku, E.N. Emotional intelligence of library leaders and innovative library services in south east Nigeria. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 3, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, A.K. Emotional intelligence and employees’ innovator role: The moderating effect of service types. Asian Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramy, A.M.; Beydokhty, A.A.A.; Jamshidy, L. Correlation between emotional intelligence and creativity factors. Int. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2014, 2, 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, F. General intelligence, emotional intelligence and academic knowledge as predictors of creativity domains: A study of gifted students. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3, 1218315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, F.; Ozer, E.; Deniz, M.E. The predictive level of emotional intelligence for the domain-specific creativity: A study on gifted students. Educ. Sci. 2016, 41, 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sakkijha, J.M.; Hamdan, R.H.; Al-Nabulsi, T.M.; Alzougool, B. The impact of emotional intelligence on employees’ creativity in the innovation companies in Jordan. Ubiquitous Comput. Commun. J. 2015, 9, 1472–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Pérez-González, J.C.; Romo, M.; Matthews, G. Divergent thinking and stress dimensions. Think. Ski. Creat. 2015, 17, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerci, A.B.; Ozer, L. Recovery behaviors in education: The role of innovativeness and emotional intelligence. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 2018, 26, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaei, M.R.; Siuki, M.E. A study of relationship between emotional intelligence and innovative work behavior of managers. Manag. Sci. 2014, 4, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sordia, N.; Martskvishvili1, K.; Neubauer, A. From creative potential to creative achievements: Do emotional traits foster creativity? Swiss J. Psychol. 2019, 78, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, A.M.; Al-Shaikh, F.N. Emotional intelligence at work: Links to conflict and innovation. Empl. Relat. 2007, 29, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajpour, M.; Moradi, F.; Jalali, S.E. Studying the influence of emotional intelligence on the organizational innovation. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Urban Manag. 2018, 3, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, H.; Tomita, H.; Taki, Y.; Kikuchi, Y.; Ono, C.; Yu, Z. The associations among the dopamine D2 receptor Taq1, emotional intelligence, creative potential measured by divergent thinking, and motivational state and these associations’ sex differences. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M. A study on the relationship between emotional intelligence and creativity of the undergraduate students in Kolkata. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2019, 14, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakalerou, M. Emotional intelligence competencies as antecedents of innovation. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 14, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ulutas, I.; Macun, B. Emotional Intelligence and Innovativeness of Preschool Teacher Candidates. In Educational Research and Practice; Koleva, I., Duman, G., Eds.; St. Kliment Ohridski University Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017; pp. 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfradt, U.; Felfe, J.; Koster, T. Self—Perceived emotional intelligence and creative personality. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 2002, 21, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, F.; Trout, I.Y.; Hartzell, S. How are entrepreneurial intentions affected by emotional intelligence and creativity. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2019, 27, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L.A.; Kafetsios, K.; Bouranta, N.; Dewett, T.; Moustakis, V.S. On the relationship between emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. R 2008, 15, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. Emotional intelligence, conflict management styles, and innovation performance. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2015, 26, 450–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V.; Tipton, E.; Johnson, M.C. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Res. Synth. Methods 2010, 1, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Tipton, E. Robust variance estimation with dependent effect sizes: Practical considerations including a software tutorial in Stata and SPSS. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Z.; Tipton, E. Robumeta: An R-package for Robust Variance Estimation in Meta-Analysis. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02220 (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Pustejovsky, J.E. clubSandwich: Cluster-Robust (Sandwich) Variance Estimators with Small-Sample Corrections. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/clubSandwich/index.html (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Viechtbauer, W. Accounting for heterogeneity via random-effects models and moderator analyses in meta-analysis. J. Psychol. 2007, 215, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, M.A. Reporting effect size estimates in school psychology research. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 653–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dusseldorp, E.; Meulman, J.J. Meta-CART: A tool to identify interactions between moderators in meta-analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2017, 70, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Re, A.C.; Hoyt, W.T. MAd: Meta-Analysis with Mean Differences (R Package Version 0.8-2). Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MAd (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Orwin, R.G. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. J. Educ. Stat. 1983, 8, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S.; Linn, M.C. Gender similarities in mathematics and science. Science 2006, 314, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What Is Emotional Intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D.J., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A.; Ramalho, N.; Marin, E. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.C.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Lee, J. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, N. What cognitive intelligence is and what emotional intelligence is not. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, M.; Antonietti, J.P.; Mikolajczak, M.; Luminet, O.; Hansenne, M.; Rossier, J. What is the ability emotional intelligence test (MSCEIT) good for? An evaluation using item response theory. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, A. The validity of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) as a measure of emotional intelligence. Emot. Rev. 2012, 4, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, B.; Hardesty, D.; Childers, T. Consumer emotional intelligence: Conceptualization, measurement, and the prediction of consumer decision making. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R.E.; Nusbaum, E.C.; Silvia, P.J. Does insight problem solving predict real-world creativity? Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, R.; Sorrel, M.A.; Fernandez-Pinto, I.; Extremera, N.; Fernandez-Berrocal, P. Age and gender differences in ability emotional intelligence in adults: A cross-sectional study. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, J.P.; Mackay, S.J.; Lewis, S.J.; Lane, S.; White, P. An international study of emotional intelligence in first year radiography students: The relationship to age, gender and culture. Radiography 2016, 22, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Luminet, O.; Leroy, C.; Roy, E. Psychometric properties of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire: Factor structure, reliability, construct, and incremental validity in a French-speaking population. J. Pers. Assess. 2007, 88, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousis, I.; Kazi, S. Factorial invariance and latent mean differences of scores on trait emotional intelligence across gender and age. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, L. Validation of emotional intelligence scale in Chinese university students. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A. Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albas, C.; Albas, D. Emotion Work and Emotion Rules: The Case of Exams. Qual. Sociol. 1988, 11, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. A meta-analysis of the relationship between individual emotional intelligence and workplace performance. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2011, 43, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.H. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Markus, H.R. Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity: A cultural analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).