1. Introduction

In April 2012, the Argentine State nationalized the Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales S.A. YPF company. This was a clear case of property rights being expropriated by a government, and President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner ratified the decree by which the company was declared a public utility. This nationalization culminated the deteriorating relations between Repsol and Argentina’s government, which was evidenced months previously by the provinces of Neuquén and Mendoza withdrawing their licenses [

1]. The Argentine State justified its action by citing Repsol’s lack of investment and the country’s need to become energy self-sufficient [

2]. However, the real reason for nationalizing was related to the discovery of the Vaca Muerta deposit, which would increase Argentina’s gas and oil reserves [

3]. The Argentine government designed a strategic plan for YPF with the aim of finding new investors for Vaca Muerta. The goal was to achieve full energy self-sufficiency over a five-year period. This is why an estimated investment of 37.2 billion dollars was budgeted, of which YPF would contribute 70%, while 18% would be financed through the issuance of debt and the remaining 12% would correspond to the contribution of foreign investors [

4]. However, YPF privatization failed to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), as the country’s legal framework was very fragile. This was evidenced by the fact that the Argentine State had not respected the property rights of a foreign company.

This instance of expropriation is related to the seminal contribution of North and Weingast [

5] on institutional frameworks and the credibility of a state’s commitment. One of the main factors for economic growth is the performance of the state. If the state is at the service of certain sectors and there is a certain risk that it will act in benefit of those sectors, promoting perverse effects for society, the institutional structure, and the Constitution itself, they must seek formulas that restrict the possibilities of predatory action by the state and guarantee the creation of rules of the game that safeguards the benefit of the collectivity, not only the benefit of reduced elites that are well interrelated with the state apparatus. Moreover, enforcement mechanisms are of paramount importance since although there are ex-ante incentives for rulers and political actors to approve norms that seek growth and general welfare, there may be no ex-post mechanisms to enforce existing norms. Faced with a state that does not respect property rights and behaves in a predatory manner, as in this case study, North, Summerhill, and Weingast [

6] established that the costs of judicial proceedings can be high—which underscores the advantage of a voluntary agreement between parties. For this reason, both parties would prefer a private agreement between the parties: Repsol because it understood the maxim that a "bad agreement is better than a good lawsuit" and the Argentine government because it understands that in order to achieve new investors and stable agreements with other companies, it is better to resolve the conflict with the company which had owned YPF and had resorted to the courts.

This paper undertakes an institutional analysis of the expropriation, and it thoroughly examines the Argentine government’s decision as well as the effects of that decision on the economy and on the credibility of Argentina’s institutional framework. The theoretical bases underlying the analysis of such cases are those advocated by the new institutional economics (NIE). The NIE is essential for understanding the social, political, and economic factors at play in the YPF case. Hence, the institutional analysis developed here focuses on Williamson’s second level of analysis [

7], which studies a society’s system of government, political framework, and formal rules. Although there have been several studies on the expropriation of YPF [

1,

3,

8,

9,

10,

11], this paper, using the NIE, incorporates new factors from relevant studies that provide a holistic analysis, which assumes that the role of the individual must be reconciled with the performance of institutions. This contextualization of the individual in his institutional environment allows us to show the insufficiencies of the idealized model presented by the pre-Coasean neoclassical economy, where there are no transaction costs, there is perfect rationality, and the historical performance of the institutions has no consequences in the present. In this way, with this analysis, the importance of the application and fulfillment of norms is emphasized, which is highly imperfect in Argentina. Specifically, the paper incorporates the analysis of Argentina’s institutional structure, since the present policy presents a situation of dependence on past institutional conditions. A concept that North called "path dependence" [

12]. In addition, this study analyzes how resolution of the conflict was achieved through an agreement between parties that circumvented the judicial process. This analysis is based on the relationship between institutional change and economic development. Key to understanding proper application of the prevailing rules is a third-party enforcement mechanism. Such a mediator is empowered to impose resolutions and establish sanctions. Yet that third party, in resolving conflicts, might not enforce the rules perfectly. Therefore, a private agreement between parties is one way to avoid the possibility of a bad solution imposed by a third party. This paper analyzes an illustrative case in which the affected parties prefer making a “two-band” agreement to involving a third agent.

Examining the Argentine YPF case should yield applicable lessons for other Latin American and emerging economies, especially in terms of investment protection and the lack of subsequent FDI.

This paper is structured in 5 sections (

Figure 1).

Section 2 reviews the fundamentals of the new institutional economics and analyzes the institutional framework of the Argentine State to understand its policy-making.

Section 3 focuses on the study of Argentina’s energy resources and an assessment of the importance of the discovery of the Vaca Muerta reserves.

Section 4 analyzes the legality of YPF’s expropriation and how it is resolved by agreement between the parties and not by judicial means. In addition, it analyzes how this expropriation and its circumstances deteriorated the investment climate in the country.

Section 5 presents the conclusions of the paper.

3. Argentina’s Hydrocarbon Resources and the Vaca Muerta Discovery

In 2012, the year of YPF’s expropriation, Argentina was—among all South American countries—the largest producer of natural gas and the fourth-largest producer of oil. Yet, since the beginning of the 21st century, domestic consumption has grown while energy production has declined; hence, the country has become increasingly dependent on energy imports. For this reason, Argentina enacted restrictive regulations and introduced taxes on energy exports. In addition, the country’s executive branch offered tax incentives to companies willing to form alliances with Enarsa, the state energy company [

26].

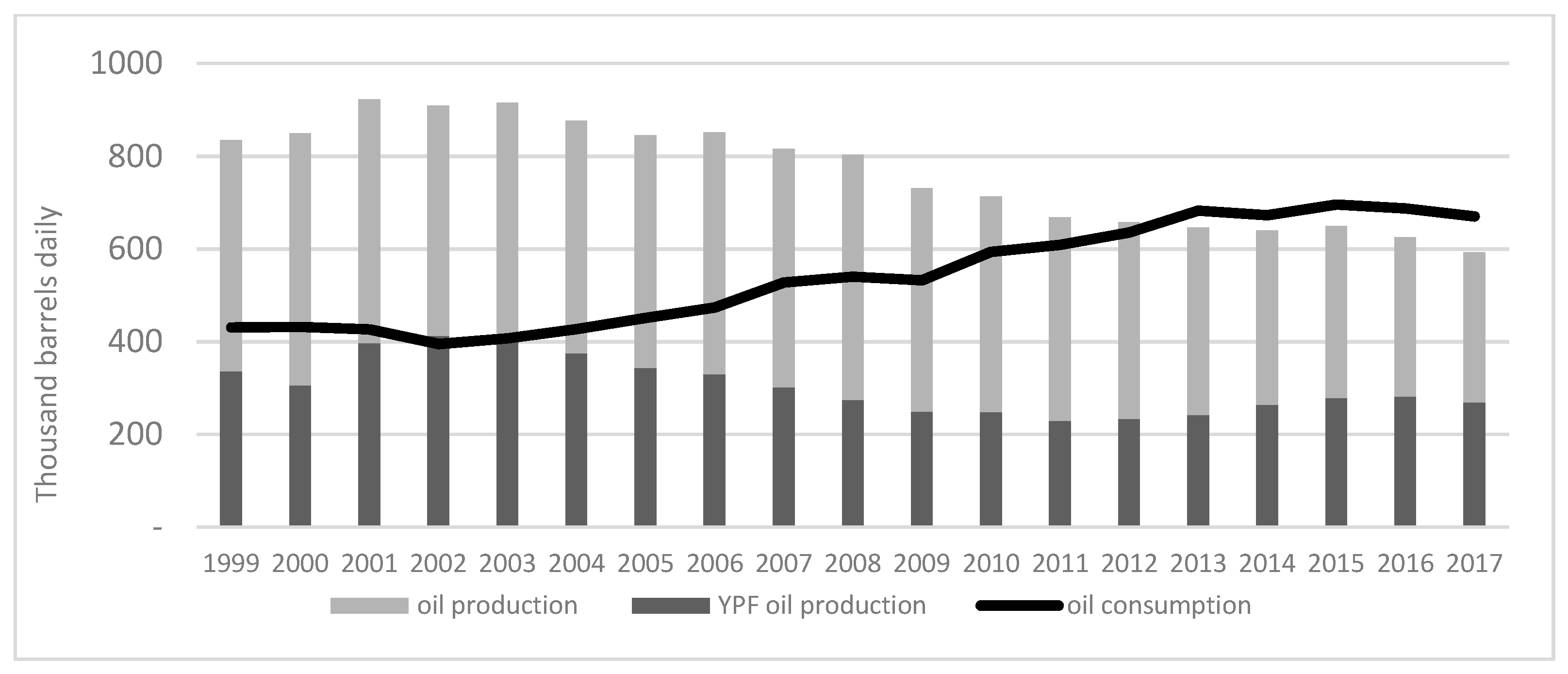

Although Argentina was energy self-sufficient through 2012, in 2013 it began importing hydrocarbons in order to satisfy domestic consumption (

Figure 2). This trend can be explained by several factors, of which the first is the large amount of national crude exported to neighboring countries. That amount has been increasing since 2008 even as national production began a precipitous decline. In response to this difficulty in meeting the country’s energy needs, the Argentine government implemented a package of measures that restricted exports; in 2010, exports were limited and a new tax was applied. The results of this new regime were visible as soon as the following year. In 2011, Argentina exported about 60 million barrels of crude oil per day, or 40% less than its 2010 exports [

27]. The second factor was the country’s relatively low level of exploitation activity combined with the maturity of wells that had already been exploited. The country’s oil industry growth was restricted also by a fiscal policy that included a 35% tax on profits and a 12% royalty on production value (although these percentages varied by province). Finally, the third factor in Argentina’s loss of self-sufficiency was labor unrest in the Argentine hydrocarbon sector between the end of 2010 and the start of 2011. These protests amplified the downward trend of oil production. For example, the strike at Cerro Dragón halted production of some 95,000 barrels of oil per day—15% of total Argentine production. Several strikes were called in 2012, also [

27].

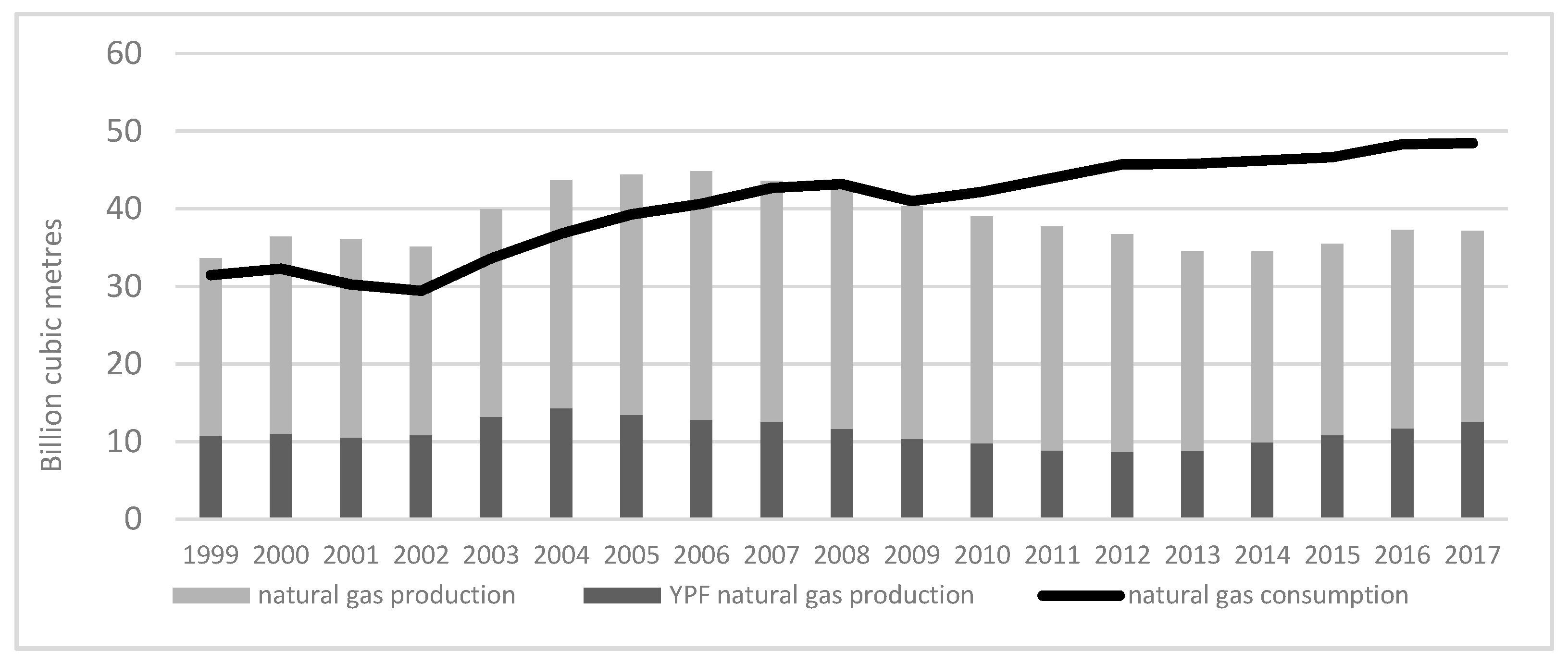

With regard to natural gas, Argentina headed the list of largest producers and consumers in Latin America until the end of the 20th century [

29]. Yet, when natural gas production declined by more than 10% after 2001 (see

Figure 3), the country increased its imports; by 2008, Argentina had become South America’s largest importer of gas. However, the discovery of Vaca Muerta meant that Argentina now held one of the world’s largest natural gas reserves. Such reserves are valuable because the supply of natural gas has seasonal “stops”—as when, during the winter, supplying homes has priority over supplying industry. Seasonal shortages occur also in the summer, during which high consumption levels can lead to supply cuts [

30].

The natural gas sector is politically active in Argentina. In 2001, the government regulated natural gas in order to guarantee its access and to fight inflation. This policy had the effect of discouraging both FDI and production, which in turn stimulated consumption. The legislation also increased import volumes. In response—and to stimulate the production and exploitation of unconventional natural gas resources—the Argentine government promoted its Gas Plus program, which allowed companies to sell natural gas from such deposits at higher prices [

31].

In 2011, the Argentine energy sector was highly dependent on oil and natural gas. The country’s increasing energy exports, depletion of its deposits, and governmental conflicts at various levels (both central and provincial) endangered the stability of Argentina’s energy supply. Fortunately, Vaca Muerta was discovered that same year. This oil deposit is located in the province of Neuquen and covers 30,000 km

2, of which 12,000 km

2 were owned by Repsol-YPF. To estimate the volume of reserves, Repsol-YPF hired Ryder Scott to carry out a geological study on 27% of the total area. That study, whose results are summarized in

Table 1, found that 77% of the ground beneath its surface would contain oil (with the remaining areas containing mostly “dry gas”). According to a 2013 report issued by the International Energy Agency, Vaca Muerta reserves would amount to 27 billion barrels. The estimates published in Repsol (2012) indicate that such an amount would increase Argentina’s reserves by 1000% [

32].

The company with the largest volume of production in Argentina during 2012 was Repsol-YPF, which accounted for nearly a third of the country’s total oil production [

33]. It was during that year that YPF was expropriated by the Argentine government. Repsol-YPF also produced a fifth of the country’s natural gas, which made it the second-largest gas producer in Argentina. Pan American Energy (PAE), which was owned by BP and Bridas Corporation, ranked number 2 in oil production; it accounted for an estimated 20% of the oil produced in this country. Foreign companies (including Chevron, Petrobras, and Sinopec Group) also figured prominently in the Argentine oil market.

4. The Process of Expropriation of YPF: From the Court to the Agreement between Parties

4.1. Expropriation of YPF

Repsol has been the main shareholder and owner of YPF since 1999. Until the end of 2011, relations between the Spanish company and the Argentine government had been cordial. However, tensions between them grew until, in April 2012, the Argentine government declared YPF a public utility and nationalized it.

Before this expropriation, the government initiated various actions directed toward Repsol. In November 2011, the Argentine government warned the company about its low investment in YPF. This warning was followed by various tax inspections that concluded in administrative reprimands. The situation worsened when five governors rescinded the exploitation contracts that their provinces had signed with Repsol-YPF; this action led to a 12% loss of oil production in Argentina [

3].

In light of these circumstances, Repsol-YPF’s stock price began to fall—at which point the president of Repsol requested an audience with the Argentine president. When this request was denied, Repsol’s president sent a letter to the government describing investment projects amounting to $3.5 billion (US), along with plans for exploitation of the Vaca Muerta deposit. However, this effort was not enough to stave off the Argentine government’s expropriating intentions.

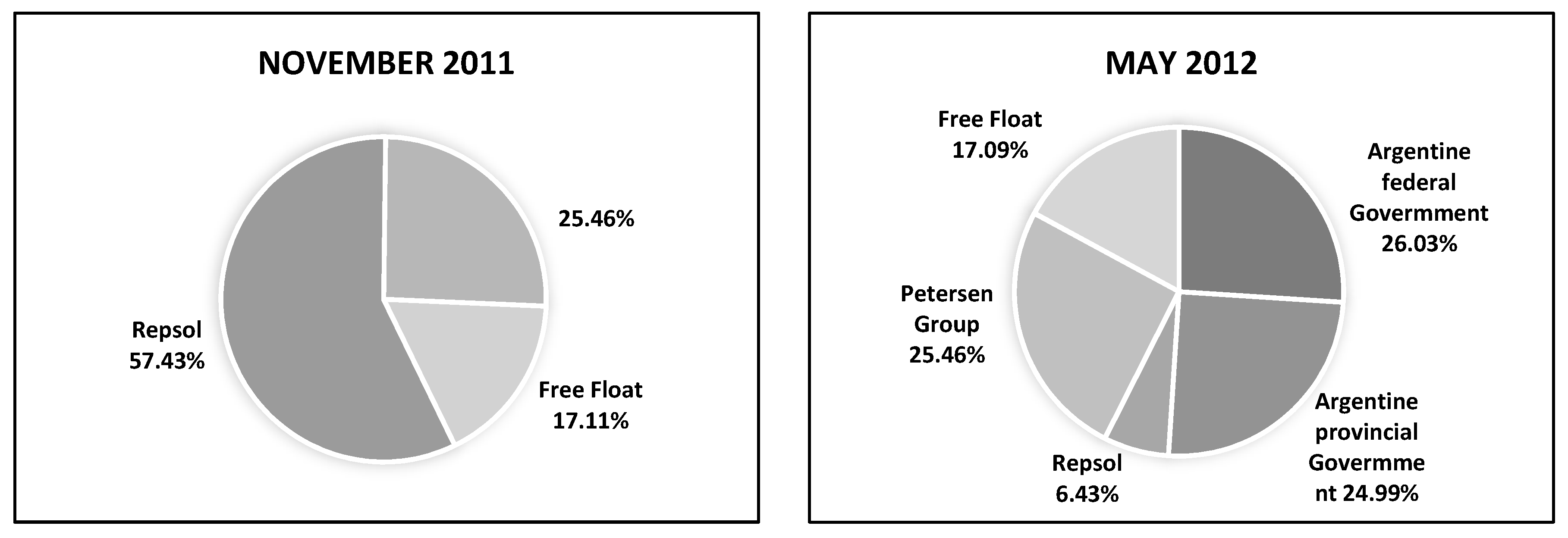

The dispute concluded on April 16 2012, with the expropriation of 51% of YPF’s shares, of which Repsol had previously owned 57.43%. Among the expropriated shares, 26.01% were distributed to the federal government and 24.99% to the provincial governors (see the right-hand panel of

Figure 4).

The government’s action was underwritten by a series of legal decisions that began on April 16 2012, with the publication of Decree No. 530/2012 (B.O. 16-04-12). This bulletin stated that the “transitory intervention” of YPF would be accomplished with 30 days—a decree that made it possible for the Argentine executive power to declare that 51% of YPF’s assets were now owned, through Class D shares, by the public. Other decrees were also published: Decree No. 557/2012 (B.O. 19-04-12), which extended the scope of Decree No. 530/2012 to YPF GAS (which was expropriated on April 18, 2012); and Decree No. 732/2012 (B.O. 16-05-12), which extended the interventions into YPF and YPF GAS.

The entire operation was based on the “National Hydrocarbons Sovereignty” Law No. 26.741 (B.O. 7-05-12). Article 7 of that law declared that 51% of YPF’s assets were of public interest and therefore subject to expropriation: “of national public interest and as a priority objective of the Argentine Republic the achievement of self-supply of hydrocarbons, as well as [the] exploration, exploitation, industrialization, transport and commercialization of hydrocarbons, in order to guarantee economic development.”

Cristina Kirchner, Argentina’s president at the time, justified the nationalization of YPF by arguing that it was necessary to achieve energy self-sufficiency and to reduce gas and oil imports. However, Bermejo and Garciandía [

10] attributed the expropriation to three entirely different causes. First was the successive withdrawal of exploitation licenses by provincial governors (Governors of provinces (e.g., Neuquén and Mendoza) withdrew their licenses previously issued to the Spanish company on the grounds of insufficient investment.); second was the discovery of Vaca Muerta’s unconventional oil deposits, which were owned by Repsol-YPF. A third factor was the Kirchner administration’s unpopularity, as bad economic data (combined with mismanagement of a railway crisis) reduced support for the president. Hence the executive may have sought to mollify critics by taking actions that might improve Argentina’s bottom line.

4.2. Debate over the Legality of Expropriating YPF

The nationalization of YPF without any compensation stimulated political and academic debate on state expropriations and property rights. From the perspective of international law, a nationalization process must be analyzed in terms that include the compensation involved. Moreover, Argentine law itself stipulates that compensation must proceed any nationalization.

The Argentine statute most relevant to this nationalization is Law 26.761, which states that “the expropriation processes will be governed by the provisions of Law No. 21.499 and the National Executive Power will act as expropriator”. Note that the “National Expropriations” Law 21.499, promulgated in 1977 under the Videla dictatorship, established that nationalization could be justified only on the grounds of public utility. President Kitchner’s rationale relied on the existence of this public utility, but that contention was hotly debated.

Article 17 of the Argentine Constitution speaks to this matter as follows: “The expropriation for cause of public utility, must be qualified by law and [be] previously indemnified”. In this case, the “public utility” justification for expropriating was based on claiming that the country’s energy sovereignty was seriously endangered by the main shareholder’s (i.e., Repsol’s) “short-term policy”. For that purpose, the Argentine government drew attention to the decline in production, the reduced investments, and the decrease in oil and gas reserves. Irrespective of this argument’s merits, there was no prior compensation and so the expropriation violated Article 17 of the Argentine Constitution.

The YPF bylaws (written after the company’s privatization by President Menem) state that, “if the National State exercises control over 49% or more of the share capital, [then] it must make a public offer to acquire all the actions of society” [

34] (pp. 29). The Argentine executive disregarded this clause, which harmed Repsol shareholders. Spain and Argentina are signatories of a bilateral treaty in effect since 1992. Article V of that treaty—an agreement for the promotion and reciprocal protection of investments between the Argentine Republic and the Kingdom of Spain—reads as follows: “The expropriation must be applied exclusively for reasons of public utility in accordance with the legal provisions and in no case should be discriminatory. The Party that adopts any of these measures shall pay the investor or its rightful owner, without undue delay, adequate compensation in convertible currency.” It is difficult to argue that this particular nationalization was not discriminatory, since 51% of YPF’s expropriated shares belonged to Repsol (57.43%) and neither the Petersen group shares (25.46%) nor the shares listed on the stock exchange (17.11%) were expropriated [

1].

4.3. A Third-Party Solution: Judicial Proceedings

Repsol, supported by the high Spanish civil service, initiated several legal proceedings intended to force the Kirchner government to compensate for its expropriation. These proceedings included Repsol’s claims that the government’s action was unconstitutional.

Within a week of the expropriation, the Spanish Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism sought to protect European production by announcing the allocation of quotas to national biodiesel production. This measure’s introduction reflected Argentina being the world’s largest importer of biodiesel; in 2011, the country consumed almost half of its own production (719,473 of 1.6 million tons). However, the measure was never implemented because the quotas were revoked before it became effective.

On May 15 2012, Repsol notified the Argentine presidency that the Treaty of Promotion and Protection of Investments (in terms of FDI) between Argentina and Spain had been breached. This statement was sent to the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes, which reports to the World Bank. Repsol claimed compensation of $ 10.5 billion for the expropriation of 51% of YPF. The parties were given six months to reach an agreement, but they were unable to do so. On December 3 2012, Repsol filed a request for arbitration, which was admitted on December 21 2012.

Repsol took its claim beyond European borders by filing (on July 5 2012) a lawsuit in the Southern District Court of New York before the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). In this lawsuit, Repsol denounced YPF for failing to comply with the information requirements to which companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange are bound. Repsol alleged that the Argentine government had not submitted documentation specifying YPF’s future plans or dividend policy (as required by SEC Section 13D; see [

35]).

In a shareholders’ meeting on May 31 2013, YPF decided to take legal action against Antonio Bufrau (a former president of the company) and all those persons who allowed payments to members of the board of directors. The lawsuit alleged that the formal procedures for remunerating the company’s management team between 2003 and 2011—the period during which Repsol was the majority shareholder—had not been followed.

4.4. Resolution of the Conflict: Agreement between Parties

Recall that, in the first six months after expropriation of YPF, various legal proceedings were initiated by Repsol and by the Argentine government. Repsol pursued monetary compensation, a legal–institutional offensive that the government attempted to counteract.

In parallel to the judicial process and in order to seek new investors, the Argentine government re-designed the strategy for investing in the Vaca Muerta deposit. However, the change from a privatized YPF model to one with the expropriated company modified the institutional balance and reduced the incentives of foreign companies to invest in Argentina. As a result—and despite the attractive commercial possibilities of Vaca Muerta—the YPF alliance with new partners was not as successful as expected. Julio de Vido, Argentina’s Planning Minister and YPF interventor himself initiated contact with energy sector multinationals such as Petrobras (Brazil), Exxon (United States), and Talisman (Canada). Although there were several attempts to reach an agreement with China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC Group) and Petróleos de Venezuela, none was made [

36]. FDI agreements were made with the oil companies Chevron, Down, Pampa, and Pluspetrol. However, these agreements were less beneficial than expected for YPF and the Argentine State: investments were for smaller amounts than anticipated, the operating costs were supported mostly by YPF, the exploitation periods were short, and the companies demanded tax benefits. When expropriating YPF, Argentina exhibited an institutional environment where expropriations need not be accompanied by monetary compensation and where legal and economic guarantees are not respected. This environment was not attractive to foreign investment, and all investors willing to assume that risk demanded high interest rates in return.

Given the extent of litigation and the declining levels of foreign investment, Argentina decided to negotiate an agreement directly with Repsol. So, on May 8 2014, the Argentine Republic delivered Argentine public debt securities to the oil producer. This compensation was in the form of different types of bonds and in the total nominal amount of more than

$5.3 billion [

37]; see

Table 2. The average value of the bonds was calculated during 90 days before the deadline of April 30 2014, based on quotes provided by five highly regarded international banks.

In addition to providing compensation for the expropriated shares of YPF and YPF GAS, the agreement sought to end all litigation between the parties. Their settlement agreement included the following provisions:

- 1)

The Argentine Republic and Repsol are to desist from pursuing any judicial and arbitral actions already initiated;

- 2)

Repsol renounces the right to make any claims for expropriation; and

- 3)

The Argentine Republic waives responsibility for Repsol as a shareholder and manager of YPF and YPF GAS.

Another clause of the agreement states explicitly that, if these provisions were not met, then Repsol could demand compliance from an arbitral tribunal.

Upon this resolution of the conflict, Repsol began its complete dissociation from YPF. On May 7 2012—one day before delivery of the bonds—Repsol sold 11.86% of the YPF Class D common shares to Morgan Stanley & Co. LLC. The pre-tax surplus value of these shares, which were sold through American Depositary Shares, reached

$ 622 million. In turn, Morgan Stanley sold the shares at a discounted price of

$ 26.91 each [

39].

On May 9 2014, when its agreement with the Argentine government was already final, Repsol sold all the BONAR 24 bonds to JP Morgan Securities PLC. The BONAR 24 was precisely the bonus created specifically for this operation. This bond was not quoted in the market, so it was the first to be sold [

40]. The transaction closed on May 13 when Repsol agreed with JP Morgan to sell the entire portfolio of the BONAR X and DISCOUNT 33 bonds along with part of the BODEN 2015 bond package. This sale closed on May 16, since Repsol’s strategy was to rid itself of the compensatory bonds as soon as possible. In so doing, Repsol reduced its debt held by the Argentine Republic by

$4815 million [

37].

Finally, on May 23 2014, Repsol broke all ties with YPF and sold nearly half of that company’s capital. This sale of Repsol’s interests in the Argentine oil company generated

$1311.3 million. All bonds still in Repsol’s possession (e.g., the BODEN 2015 bonds) were acquired by JP Morgan Securities for

$ 117.36 million [

41].

4.5. FDI in Argentina and the Effects of Nationalization on Foreign Direct Investment

In the 1990s, Argentina was one of the countries with the highest FDI in Latin America. The favorable investment policy, promoted by the government, its incorporation into Mercosur, and the capital account liberalization promoted a favorable investment climate, which reached its peak in 1999 (US

$ 24,000 million) [

42]. One of its main foreign investors in that decade was Spain, along with the U.S. Although, at first, Spain’s interests were directed towards the investment of privatized public services, the strategy quickly focused on participating in the banking sector and especially in the energy sector. Proof of this is the acquisition of YPF by Repsol in 1999.

However, the crisis suffered by the country in 2001 completely changed the investment scenario. While global investment in 1999–2000 was US

$ 34.406 million, in 2001–2002 it fell to US

$ 2.951 million [

42]. The effects of this crisis moderated, but Argentina’s 1990 FDI boom did not happen again. The main reason why investors were reluctant to invest in the country was due to the policy change implemented in Argentina after the crisis. Since 2003, Argentina has turned to nationalism. His government justified this new policy in order to restore the balance of payments, reduce inflation, and promote employment [

43]. This nationalist policy culminated in the nationalization of YPF in 2012.

The fact that the nationalization of the YPF was carried out without respect for property rights affected the business environment, so the FDI deteriorated rapidly. This is illustrated by the fact that the FDI fell from US

$ 12.116 million in 2012 to US

$ 9.082 million in 2013. In addition, the number of mergers and acquisitions involving a foreign company declined. In 2012, there were only two transactions of this type, both in the energy sector: The first one corresponds to the sale of the Compañía General de Combustibles to a foreign investor whose origin was not revealed; the second one involved Andes Energía PLC [

44].

In 2014, the FDI registered a year-on-year variation of -41%, decreasing to US

$ 6.612 million [

45]. Although the negative trend had continued since 2012, this unfavorable result was exacerbated by the sale of 12% of YPF’s shares that Repsol still owned (

Figure 5). This fact negatively affected the balance of payments, since a large percentage of these shares were acquired by Argentine companies. However, if Repsol did not sell its shares, the amount of the FDI would not have fallen so sharply. In fact, the FDI experienced a recovery in the second half of 2014, when the indemnity arrangement between Repsol and the Argentine State had already become effective.

On the other hand, to reflect the importance that the nationalization of YPF has had, it is important to analyze the evolution of several indicators that may show how investors perceived the Argentine institutional framework after the expropriation. The indicator on the ease of doing business in this country, provided by the World Bank’s Doing Business study, shows that Argentina dropped positions on the list. Its position went from 139th in 2012 to 185th in 2013 [

46]. This decrease in ranking was due to the fact that its ranking on the list of investor protection index and contract compliance index had decreased by three and two positions, respectively [

47]. Argentina’s fall in ranking was consolidated with the data collected in the Doing Business report for 2014. In this sense, Argentina’s situation in the 2014 report was much worse than that of other countries in the region, such as Colombia, Peru, Chile or Uruguay, and was below the Latin American average [

48].

The country’s loss of credibility also directly affected YPF, making it difficult to find new investors for Vaca Muerta despite the advantageous conditions proposed by the Argentine government. It was the Argentine Minister of Planning and YPF controller who initiated contacts with various energy companies such as Petrobras S.A. (Brazil), ExxonMobil Corporation (USA), and Talisman Energy Inc. (Canada), contacts that did not progress. In addition, there were several attempts to reach an agreement with CNOOC Group and Petróleos de Venezuela S.A., but none of them were successful. Finally, in July 2013, more than a year after negotiations began, YPF signed with Chevron Corporation an investment agreement of US

$ 1.240 million (less than the expected US

$ 1.500 million), followed by two more agreements with Pluspetrol S.A. and Pampa Energía S.A. [

3]. These three agreements can be understood as a great victory for YPF, however, they were not so great. To attract foreign investment, YPF had to accept a lower-than-expected investment and guarantee various tax advantages, which lowered the expected return on the investment.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the nationalization of YPF is framed within institutionalist approaches that assume the importance of reconciling the role of institutions and individuals, in a coherent manner, with recent trends in the NIE. Thus, the role of institutions is key in explaining, from a macro perspective, the effects on economic reality, either by explaining how the expropriation of YPF affects the management of hydrocarbon resources in Argentina or how it damages the FDI. But alongside this more macro-analytical perspective, which studies the role of institutions as explanatory exogenous elements of economic reality, a micro-analytical perspective is also incorporated that takes into account the incentives that determine the behavior of key agents for the institutional framework and its change. Thus, the decision to expropriate YPF can be explained in terms of the incentives that the institutional structure determines for Argentine political decision-makers, who will seek re-election and increase their degree of decision-making on key factors.

The institutional mechanisms that guarantee the state’s commitment is a central issue for successful economic, political development, and energy sustainability [

49,

50,

51]. That commitment’s credibility can be enhanced by limiting the state’s ability to act—in other words, by creating mechanisms to prevent delegation of power that encourages the abdication of citizenship. The goal is to prevent the entities that control the state from appropriating property rights, which would severely depress FDI and growth. In other words, no investor wants its returns to be taken by the state. This dilemma is a fundamental one for politics [

52]. If the state does not have a reputation to maintain, then there will be more opportunities for it to expropriate and to renege on previous commitments. This is what occurred in Argentina, since the state was not viewed as respecting those rights and commitments. Therefore, political decision makers had nothing to lose by making what were, in effect, assaults on the economic rights of citizens.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Argentina was a prosperous nation in the world economy. However, the country’s trajectory throughout that century was characterized by political disorder and high instability of its institutions, a predominance of predatory interests, conflict between formal and informal institutions, the short-term horizons of political leaders, the lack of guaranteed property rights, high transaction costs, low levels of political and institutional cooperation, a relatively ineffective parliament, and an administration of justice that was not entirely impartial [

24,

25]. Hence Argentina’s institutional matrix can hardly guarantee the credibility of political commitment and respect for property rights.

When property rights extend over goods or resources of substantial economic value, the interest in expropriation increases. Argentina is a major producer of oil and natural gas in Latin America, a position it occupies owing mainly to the Vaca Muerta reserves. The existence of these reserves was known when the YPF was privatized (in 1999) and hence when it was expropriated (in 2012). It follows that the expropriation accounted for potential future performance and for the possible underestimation of required investment costs.

The distribution of Argentina’s population is fundamental to explaining the country’s institutional design and also to understanding the expropriation process. In particular, the electoral incentives of political leaders played an important role in the process. The president of Argentina and the leaders of her party, in moments of low popularity, justified the expropriation in terms of defending the country. By ignoring the costs of this decision, the “populist” component of this argument managed to penetrate broad bases of the electorate, who scapegoated FDI for the country’s problems. The government’s political elites could then appropriate the right to decide on resources of great value while consolidating their power and increasing the likelihood of their re-election.

The case of YPF’s expropriation has laid bare the visibility of Argentina’s fragile institutional framework. The government’s strategy for regaining autonomy over hydrocarbon resources and thereby rendering the Kirchner executive stronger actually ended up undermining the country’s international reputation. Neither the process specified in the bilateral treaty nor other established international procedures managed to ensure respect for the rules of the game and the rights of private property. The actions of Argentina’s government and its public offices showcased the lack of secure bases for the rights of agents in that country—an absence of commitment that discourages investment. The nationalization also made clear that Argentina’s political institutions are unable to safeguard political rights and hence democratic rights, either. This study affirms that existing incentives encourage the political class not to respect property rights or agreements with the state but rather to act in accordance with its particular interests, which may well be predatory.

The Argentine judiciary lacks independence and has exhibited a lax attitude toward compliance with the law. The expropriation made to Repsol violates the Argentine Constitution, which states that expropriation must be preceded by adequate compensation. The expropriation process followed by Argentina was impaired by its own political bureaucracy’s lack of efficiency. And because policy making involves the interaction of various factors—namely, powers, time horizons, and incentives—it is difficult to ensure the coherence, coordination, implementation, and stability of policies.

Because there was no prior compensation, the nationalization of YPF did not respect even Argentina’s deficient institutional framework; hence the government had difficulties finding partners to undertake investment in the Vaca Muerta project. So, in order to obtain those investments, the Argentine government put an end to its litigation with Repsol. The judicial procedure against an expropriating state is an imperfect institutional solution, one characterized by long duration and high transaction costs. Therefore, a private agreement would likely have been preferable: for Repsol because “a bad agreement is better than a good lawsuit”, and for the Argentine government because attracting new investors required that it resolve the conflict. In that sense, an agreement between the parties would have been a better solution than the judicial one—especially given the high transaction costs of the latter path.

This case study offers an integrated view of the Argentine political–economic reality. It documents that the country is unstable because it has failed to establish adequate credibility mechanisms and has allowed property rights to be trampled. Such an institutional framework hinders the development of efficient markets, both political and economic. Changing this institutional modus operandi is a slow and arduous task, one that may not succeed because of institutional inertia and decreasing returns.