A Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Investigate the Audit Expectation Gap and Its Impact on Investor Confidence: Perspectives from a Developing Country

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Related Literature and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Audit Expectation Gap (AEG)

- (a)

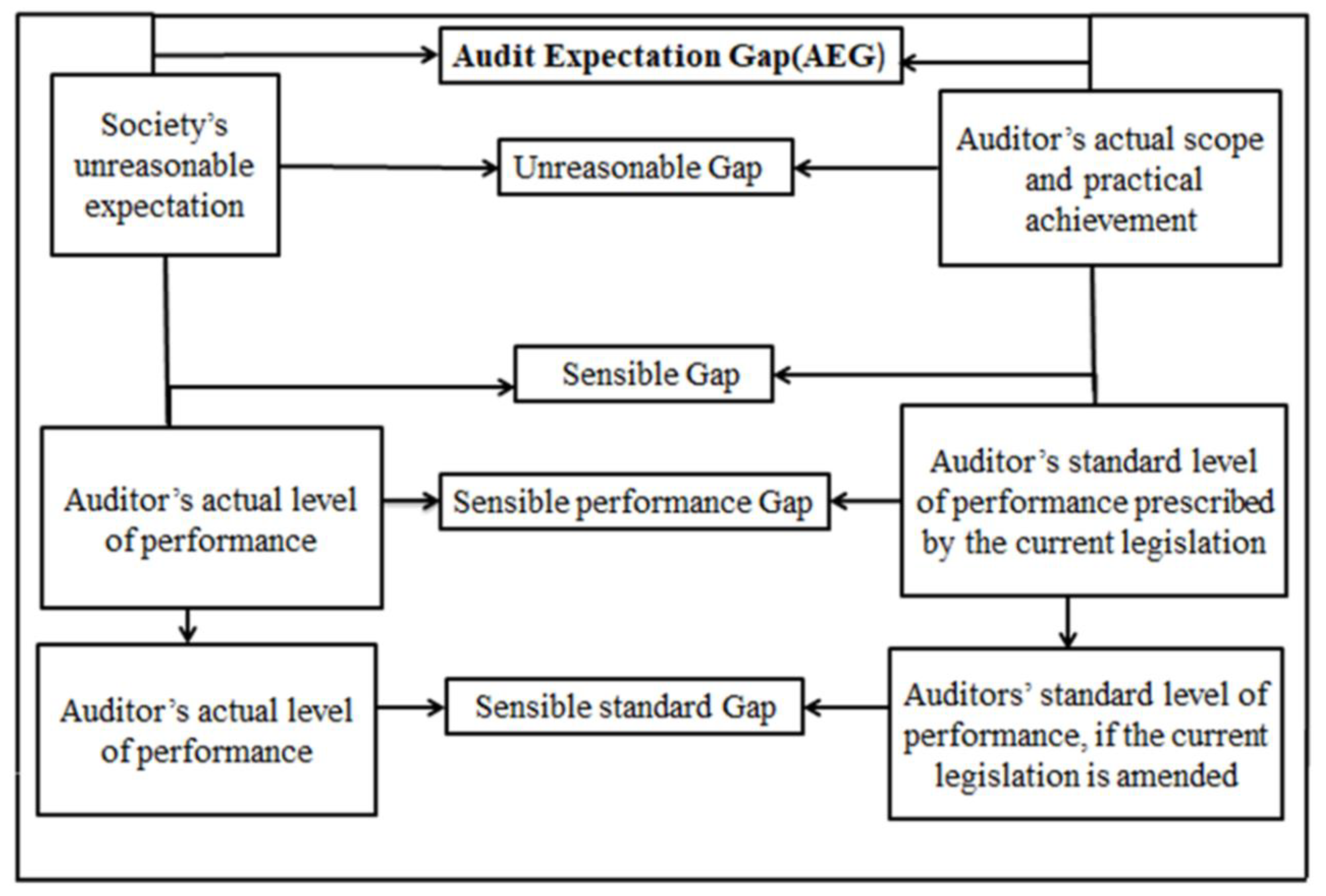

- Unreasonable gap: The gap between what the society believes in their mind what auditors can achieve and what practically they can achieve. It can also be referred to as failure of the public to understand the aim and scope of auditing and develop unreasonable expectations.

- (b)

- Sensible gap:

- (i)

- Sensible performance gap: What society can sensibly expect from the auditors about the actual level of performance of auditors and the standard of performance described by the current regulation. It can also be denoted as failure of the auditor to understand their own responsibilities under the current audit regulation regime.

- (ii)

- Sensible standard gap: What society can sensibly expect from the auditors if there is an amendment in the current legislation based on equitable demand from the participants and if it is cost-effective in doing so. It can also be mentioned as failure of the standard setters if the current standards fail to communicate auditors’ responsibilities clearly or reflect the users’ logical demand for amendments to the standards.

2.2. Auditor’s Perceived Independence (API)

2.3. Auditor’s Improved Level of Communication (AILC)

2.4. Investors’ Confidence (ICF)

2.5. The Role of Independent Audit Oversight

3. Research Method

3.1. Data

3.2. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Assessing the Measurement Model

4.2. Assessing the Structural Model

4.3. Hypothesis Testing of Direct Relationships

4.4. Hypothesis Testing of Moderating Relationships

5. Discussion, Implication, Study Limitation & Future Research Direction

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications of the Study

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Accessibility Statement

References

- Monroe, G.S.; Woodliff, D.R. Great Expectations: Public Perceptions of the Auditor’s Role. Aust. Account. Rev. 1994, 4, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Chartered Accountants of England & Wales (ICAEW). Reconciling Stakeholders Expectation of Audit. Audit Quality Forum. 2008. Available online: www.icaew.co.uk/auditquality (accessed on 5 January 2019).

- Eilifsen, A.; Messier, W.F., Jr. A Review and Integration of Archival Research. J. Account. Lit. 2000, 19, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howieson, B. Quis Auditoret Ipsos Auditores? Can Auditors Be Trusted? Aust. Account. Rev. 2013, 23, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.R.; Bédard, J.; Hauret, C.P.D. The Regulation of Statutory Auditing: An Institutional Theory Approach. Manag. Audit. J. 2014, 29, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. The Importance of Confidence and Trust: Stakeholders Perspective. 2018. Available online: https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2018/04/building-confidence-and-trust-in-capital-markets.html (accessed on 18 October 2018).

- Porter, B. An Empirical Study of the Audit Expectation-Performance Gap. Account. Bus. Res. 1993, 24, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Gowthorpe, C. Audit Expectation-Performance Gap in the United Kingdom in 1999 and Comparison with the Gap in New Zealand in 1989 and in 1999; The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, B.; Ó Hogartaigh, C.; Baskerville, R. Audit Expectation-Performance Gap Revisited: Evidence from New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Part 1: The Gap in New Zealand and the United Kingdom in 2008. Int. J. Audit. 2012, 16, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, A. Role Theory and the Management of Service Encounters. Serv. Ind. J. 1999, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, P. Audit Committees: Solution to a Crisis of Trust? Account. Irel. 2002, 34, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, B.; Simon, J.; Hatherly, D.J. Principles of External Auditing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Reporting Council (FRC). Enhancing Confidence in the Value of Audit, A Research Report Commissioned by the Financial Reporting Council. 2016. Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/382e1ad9-5b7a-4297-849b1d415420fdc4/Impact-Assessment-Audit-Regulation-and-Directive-September-2015.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- Stephen, K. Auditing’s Expectation Gap is Worse than ever Financial Times. The Financial Times. 14 January 2018. Available online: https://www.ft.com (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Sikka, P.; Puxty, A.; Willmott, H.; Cooper, C. The Impossibility of Eliminating the Expectations Gap: Some Theory and Evidence. Crit. Perspect. Account. 1998, 9, 299–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Ali, A.M.; Gloeck, J. The Audit Expectation Gap in Malaysia: An Investigation into its Causes and Remedies. S. Afr. J. Account. Audit. Res. 2009, 9, 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, C.; Moizer, P.; Turley, S. The Audit Expectations Gap—Plus Ca Change, Plus C’est La Meme Chose? Crit. Perspect. Account. 1992, 3, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Azary, Z. Fraud Detection and Audit Expectation Gap: Empirical Evidence from Iranian Bankers. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 3, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mock, T.J.; Bédard, J.; Coram, P.J.; Davis, S.M.; Espahbodi, R.; Warne, R.C. The Audit Reporting Model: Current Research Synthesis and Implications. Auditing 2012, 32, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). Commission on Auditors, Responsibilities Report: Conclusions and Recommendations; AICPA: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, G.L.; Turner, J.L.; Coram, P.J.; Mock, T.J. Perceptions and Misperceptions Regarding the Unqualified Auditor’s Report by Financial Statement Preparers, Users, and Auditors. Account. Horiz. 2011, 25, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhnke, K.; Schmidt, M. The Audit Expectation Gap: Existence, Causes, and the Impact of Changes. Account. Bus. Res. 2014, 44, 572–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). Concept Release on Auditor Independence and Audit Firm Rotation; PCAOB: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). Legal and Regulatory Environment; IFAC: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2017. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/about-ifac/membership/country/bangladesh (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Shil, N.C. Stewardship, Transparency, Accountability, and Reporting [Star]. A Journey Enlightening. Cost Manag. 2015, 43, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, B. Narrowing the Audit Expectation-Performance Gap: A Contemporary Approach. Pac. Account. Rev. 1991, 3, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, G.S.; Woodliff, D.R. An Empirical Investigation of the Audit Expectation Gap: Australian Evidence. Account. Financ. 1994, 34, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K.E.; Smith, J.K.; Lowe, D.J. The Expectation Gap: Perceptual Differences between Auditors, Jurors and Students. Manag. Audit. J. 2001, 16, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.B.; Hodge, F.D.; Kennedy, J.J.; Pronk, M.; Are, M.B.A. Students a Good Proxy for Nonprofessional Investors? Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, G.S.; Woodliff, D.R. The Effect of Education on the Audit Expectation Gap. Account. Financ. 1993, 33, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnroe, J.E.; Martens, S.C. Auditors and Investors Perceptions of the “Expectation Gap”. Account. Horiz. 2001, 15, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.M.; Claypool, G.A.; Tackett, J.A. Audit Disaster Futures: Antidotes for the Expectation Gap? Manag. Audit. J. 1999, 14, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akther, T.; Xu, F. Stakeholders Trust Towards the Role of Auditors: A Synopsis of Audit Expectation Gap. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Innovation & Management, Yamaguchi, Japan, 27–29 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Best, P.J.; Buckby, S.; Tan, C. Evidence of the Audit Expectation Gap in Singapore. Manag. Audit. J. 2001, 16, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.J.; Chen, F. An Empirical Study of Audit ‘Expectation Gap’ in the People’s Republic of China. Int. J. Audit. 2004, 8, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.; Woodhead, A.D.; Sohliman, M. An investigation of the expectation gap in Egypt. Manag. Audit. J. 2006, 21, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J.; Nasreen, T.; ChoudhuryeLema, A. The Audit Expectations Gap and the Role of Audit Education: The Case of an Emerging Economy. Manag. Audit. J. 2009, 24, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourheydari, O.; Abousaiedi, M. An Empirical Investigation of the Audit Expectations Gap in Iran. J. Islamic Account. Bus. Res. 2011, 2, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). ISA 240 Summary: The Auditor’s Responsibilities Relating to Fraud in an Audit of Financial Statement; IAASB: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, B.A. The Audit Trinity: The Key to Securing Corporate Accountability. Manag. Audit. J. 2009, 24, 156–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, S.K.; Wright, A.M. Investors, Auditors, and Lenders Understanding of the Message Conveyed by the Standard Audit Report on the Financial Statements. Account. Horiz. 2012, 26, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.; Gronewold, U.; Pott, C. The ISA 700 Auditor’s Report and the Audit Expectation Gap—Do Explanations Matter? Int. J. Audit. 2012, 16, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadzly, M.N.; Ahmad, Z. Audit Expectation Gap: The Case of Malaysia. Manag. Audit. J. 2004, 19, 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, E.; Fargher, N.L.; Geiger, M.A.; Lennox, C.S.; Raghunandan, K.; Willekens, M. Audit Reporting for Going-Concern Uncertainty: A Research Synthesis. Auditing 2012, 32, 353–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB). Proposed Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, Going Concern; FASB: Norwalk, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB). Disclosures about Risks and Uncertainties and the Liquidation Basis of Accounting; FASB: Norwalk, CT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). Invitation to Comment: Improving the Auditor’s Report; International Federation of Accountants: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). Going Concern, ISA 570; IAASB: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). Forming an Opinion and Reporting on Financial Statements, ISA700 Revised; IAASB: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, B.J.; Smith, L.M. Faculty perspectives of auditing topics. Issues Account. Educ. 1997, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mock, T.J.; Strohm, C.; Swartz, K.M. An examination of worldwide assured sustainability reporting. Aust. Account. Rev. 2007, 17, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simnett, R.; Vanstraelen, A.; Chua, W.F. Assurance on sustainability reports: An international comparison. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 937–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Liburd, H.; Zamora, V.L. The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) assurance in investors’ judgments when managerial pay is explicitly tied to CSR performance. Auditing 2014, 34, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.R.; Gaynor, L.M.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Wright, A.M. The impact on auditor judgments of CEO influence on audit committee independence. Auditing 2011, 30, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.W. Ameliorating Conflicts of Interest in Auditing: Effects of Recent Reforms on Auditors and their Clients. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Paper Audit Policy: Lessons from the Crisis. 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52010DC0561 (accessed on 22 December 2018).

- Bazerman, M.H.; Moore, D. Is it Time for Auditor Independence Yet? Account. Organ. Soc. 2011, 36, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, K.; Sunder, S. Is Mandated Independence Necessary for Audit Quality? Account. Organ. Soc. 2011, 36, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; Brandt, R.; Fearnley, S. Perceptions of Auditor Independence: U.K. Evidence. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 1999, 8, 67–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M.L.; Raghunandan, K.; Subramanyam, K.R. Do Non–Audit Service Fees Impair Auditor Independence? Evidence from Going Concern Audit Opinions. J. Account. Res. 2002, 40, 1247–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh, H.; LaFond, R.; Mayhew, B.W. Do Nonaudit Services Compromise Auditor Independence? Further Evidence. Account. Rev. 2003, 78, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.-Y.; Tan, H.-T. Non-Audit Service Fees and Audit Quality: The Impact of Auditor Specialization. J. Account. Res. 2008, 46, 199–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, H. Relevant Financial Reporting Questions Not Asked by the Accounting Profession. Crit. Perspect. Account. 1998, 9, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.; Anandarajan, A. Dimensions of Pressures Faced by Auditors and its Impact on Auditors’ Independence: A Comparative Study of the USA and Australia. Manag. Audit. J. 2004, 19, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, W.R., Jr.; Palmrose, Z.V.; Scholz, S. Auditor independence, non-audit services, and restatements: Was the US government right? J. Account. Res. 2004, 42, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Rostami, V. Audit expectation gap: international evidences. Int. J. Acad. Res. 2009, 1, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mo Koo, C.; Seog Sim, H. On the role conflict of auditors in Korea. Accounting. Audit. Account. J. 1999, 12, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, P.C.-W.; Pang, E. Investors Perceptions of Auditor Independence: Evidence from Hong Kong. e-J. Soc. Behav. Res. Bus. 2017, 8, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Morgan, K.P.; Loewenstein, G.F. The Impossibility of Auditor Independence. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1997, 38, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, Z.; Stewart, J. The Role of the Audit Committee in resolving auditor-client disagreements: A Malaysian study. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2012, 25, 1340–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, G.; Wright, A.; Cohen, J. Audit Committee Effectiveness and Financial Reporting Quality: Implications for Auditor Independence. Aust. Account. Rev. 2002, 12, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coram, P.J.; Mock, T.J.; Turner, J.L.; Gray, G.L. The Communicative Value of the Auditor’s Report. Aust. Account. Rev. 2011, 21, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddrill, S. Speech by Stephen Haddrill, Chief Executive of the U.K. Financial Reporting Council, to the European Commission Conference on Financial Reporting and Auditing on Thursday 10th February 2011. Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/news/july-2018/speech-by-stephen-haddrill-corporate-governance (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). Concept Release on Possible Revisions to PCAOB Standards Related to Reports on Audited Financial Statements and Related Amendments to PCAOB Standards; PCAOB: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). The New Auditor’s Report: Greater Transparency into the Financial Statement Audit. 2015. Available online: www.iaasb.org/auditor-reporting (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). The Auditor’s Responsibilities Relating to Other Information in Documents Containing Audited Financial Statements; ISA 701; IAASB: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, M.J.; Geiger, M.A. Investor Views of Audit Assurance: Recent Evidence of the Expectation Gap. J. Account. 1994, 177, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, R.; Kim, S.; Musa, P.M. When does comparability better enhance relevance? Policy implications from empirical evidence. J. Account. Public Policy 2018, 37, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.; Rittenberg, L. Messages perceived from audit, review, and compilation reports: Extension to more diverse groups. Auditing 1987, 7, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schelluch, P.; Green, W. The Expectation Gap: The Next Step. Aust. Account. Rev. 1996, 6, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.E.; Rezaee, Z.; Riley, R.A.; Velury, U.K. Financial Statement Fraud: Insights from the Academic Literature. Auditing 2008, 27, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, E.; Jaussaud, J. Regulation of statutory audit in China. Asian Bus. Manag. 2003, 2, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C.; Moizer, P.; Turley, S. The Audit Expectations Gap in Britain: An Empirical Investigation. Account. Bus. Res. 1993, 23, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, A. An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Auditors Independence on the Credibility of the Financial Statement in Nigeria. Res. J. Financ. Account. 2011, 2, 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Baotham, S.; Ussahawanitchakit, P. Audit Independence, Quality, and Credibility: Effects on Reputation and Sustainable Success of CPAs in Thailand. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, C.A.; Otalor, J.I. Narrowing the expectation gap in auditing: the role of the auditing profession. Res. J. Financ. Account. 2013, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J. Constructing an organizational field as a professional project: US art museums, 1920–1940. In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; Powell, W.W., DiMaggio, P.J., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 267–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hossen, M.S. Financial Reporting Act (FRA), 2015: A Revolutionary Era for Ensuring Effective Capital Market and Economic Development in Bangladesh. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2016, 16, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M. Role and Responsibilities of Professional Accountants. Speech in Seminar on Financial Reporting Act, ICMAB News. Cost Manag. 2017, 45, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Schelluch, P.; Gay, G. Assurance Provided by Auditors’ Reports on Prospective Financial Information: Implications for the Expectation Gap. Account. Financ. 2006, 46, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.C.; Bush, R.F. Marketing Research: Online Research Applications; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Karkacıer, A.; Ertaş, F.C. Independent auditing effect on investment decisions of institutional investors. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 16, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akın, F.; Ve Ece, N. Kurumsal yatırımcılar ve Türk sermaye piyasasında kurumsal yatırımcıların gelişimi üzerine bir değerlendirme (Institutional investors and an evaluation on the development of institutional investors in the Turkish capital market). Abmyo Derg. 2011, 22, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk; IBM Corp: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarque, C.; Bera, A. Efficient tests for normality, homoscedasticity and serial independence of regression residuals. Econ. Lett. 1980, 6, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Introducing LISREL; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.-M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riel, A.; Henseler, J.; Kemény, I.; Sasovova, Z. Estimating Hierarchical Constructs Using Consistent Partial Least Squares: The Case of Second-Order Composites of Common Factors. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Bagozzi, R.P. On the Nature and Direction of Relationships between Constructs and Measures. Psychol. Methods 2000, 5, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S.; Straub, D.; Rai, A. Specifying Formative Constructs in Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K. Latent Variables and Indices: Herman Wold’s Basic Design and Partial Least Squares. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Schermelleh-Engel, K. Consistent Partial Least Squares for Nonlinear Structural Equation Models. Psychometrika 2014, 79, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative Versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analyses with Readings; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Allini, A.; Aria, M.; Macchioni, R.; Zagaria, C. Motivations behind users’ participation in the standard-setting process: Focus on financial analysts. J. Account. Public Policy 2018, 37, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Auditing & Assurance Standard Board (IAASB). A Framework for Audit Quality. 2014. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/auditing-assurance/focus-audit-quality (accessed on 4 September 2018).

- Hanson, J.D. PCAOB Update—Recent Activities and Next Steps. In Proceedings of the 2016 SEC and Financial Reporting Institute Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.; Petter, S.; Fayard, D.; Robinson, S. On the Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in Accounting Research. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddrill, S. FRC’s Annual Development Audit. 2018. Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/f211c972-73ab-4bf2-b696-820eadc538bf/SH-Developments-in-Audit-FINAL-v2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

| Variable/Dimension | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Respondents Groups | ||

| Auditors | 76 | 44 |

| Investors | 98 | 56 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 141 | 81 |

| Female | 33 | 19 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Graduate | 50 | 29 |

| Post Graduate | 40 | 23 |

| Professional Degree e.g., ACA/ACMA/FCA/FCMA | 81 | 47 |

| PhD/others | 3 | 1 |

| Accounting & Audit related Experiences | ||

| 1 to 3 years | 35 | 20 |

| 4 to 6 years | 72 | 41 |

| 7 to 9 years | 46 | 27 |

| 10+ years | 21 | 12 |

| Path | Indicator Loading | Indicator Weight | T-Stat | VIF | Path | Indicator Loading | Indicator Weight | T-Stat | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARF1-ARF | 0.696 | 0.292 | 10.336 | 1.353 | ARF1-AEG | 0.467 | 0.016 | 2.411 | 1.647 |

| ARF2-ARF | 0.914 | 0.312 | 17.922 | 1.537 | ARF2-AEG | 0.470 | 0.006 | 1.988 | 1.575 |

| ARF3-ARF | 0.897 | 0.307 | 17.558 | 4.528 | ARF3-AEG | 0.346 | 0.026 | 2.070 | 4.558 |

| ARF4-ARF | 0.770 | 0.307 | 9.628 | 5.134 | ARF4-AEG | 0.347 | 0.027 | 2.768 | 5.444 |

| MUAR1-MUAR | 0.790 | 0.216 | 16.305 | 2.008 | MUAR1-AEG | 0.556 | 0.004 | 2.081 | 2.271 |

| MUAR2-MUAR | 0.871 | 0.240 | 17.833 | 2.657 | MUAR2-AEG | 0.611 | 0.019 | 2.351 | 2.923 |

| MUAR3-MUAR | 0.794 | 0.237 | 16.795 | 2.024 | MUAR3-AEG | 0.591 | 0.054 | 1.980 | 2.392 |

| MUAR4-MUAR | 0.885 | 0.244 | 20.842 | 2.999 | MUAR4-AEG | 0.623 | 0.114 | 2.068 | 3.325 |

| MUAR5-MUAR | 0.879 | 0.247 | 20.171 | 2.885 | MUAR5-AEG | 0.620 | 0.018 | 2.304 | 3.350 |

| GCRA1-GCR | 0.531 | 0.243 | 5.207 | 1.151 | GCRA1-AEG | 0.344 | 0.049 | 2.874 | 1.260 |

| GCRA2-GCR | 0.563 | 0.275 | 4.562 | 1.955 | GCRA2-AEG | 0.420 | 0.120 | 1.924 | 1.206 |

| GCRA3-GCR | 0.808 | 0.440 | 7.735 | 1.419 | GCRA3-AEG | 0.621 | 0.063 | 1.771 | 1.124 |

| GCRA4-GCR | 0.724 | 0.296 | 7.503 | 1.801 | GCRA4-AEG | 0.415 | 0.004 | 1.773 | 1.279 |

| EOA1-OA | 0.596 | 0.305 | 15.271 | 1.421 | OA1-AEG | 0.409 | 0.127 | 1.845 | 2.053 |

| EOA2-OA | 0.833 | 0.485 | 15.295 | 1.426 | OA2-AEG | 0.706 | 0.235 | 1.718 | 2.078 |

| EOA3-OA | 0.843 | 0.491 | 2.318 | 1.012 | OA3-AEG | 0.710 | 0.147 | 1.749 | 1.132 |

| RNAS1-RNAS | 0.673 | 0.262 | 8.802 | 1.195 | RNAS1-API | 0.487 | 0.085 | 2.152 | 1.292 |

| RNAS2-RNAS | 0.770 | 0.276 | 13.363 | 1.400 | RNAS2-API | 0.501 | 0.053 | 1.736 | 1.485 |

| RNAS3-RNAS | 0.039 | 0.023 | 13.273 | 1.421 | NAS3-AEG | 0.020 | 0.035 | 1.849 | 1.960 |

| RNAS4-RNAS | 0.839 | 0.383 | 18.242 | 1.900 | RNAS3-API | 0.694 | 0.151 | 2.892 | 2.156 |

| MAR 1-MAR | 0.694 | 0.344 | 8.183 | 1.250 | MAR 1-API | 0.442 | 0.042 | 3.938 | 1.333 |

| MAR 2-MAR | 0.839 | 0.411 | 15.504 | 1.565 | MAR 2-API | 0.522 | 0.043 | 3.767 | 2.663 |

| MAR 3-MAR | 0.832 | 0.500 | 14.455 | 1.450 | MAR 3-API | 0.639 | 0.189 | 3.299 | 1.736 |

| AAC1-AAC | 0.799 | 0.493 | 13.733 | 1.325 | AAC1-API | 0.601 | 0.182 | 3.315 | 1.447 |

| AAC2-AAC | 0.811 | 0.464 | 13.516 | 1.350 | AAC2-API | 0.564 | 0.083 | 3.456 | 1.510 |

| AAC3-AAC | 0.633 | 0.363 | 7.551 | 1.114 | AAC3-API | 0.442 | 0.065 | 1.730 | 1.053 |

| IAR1-EAR | 0.725 | 0.214 | 9.301 | 1.961 | EAR1-AILC | 0.488 | 0.062 | 1.772 | 2.041 |

| IAR2-EAR | 0.925 | 0.226 | 10.946 | 2.736 | EAR2-AILC | 0.501 | 0.099 | 1.769 | 2.872 |

| IAR3-EAR | 0.802 | 0.215 | 8.840 | 2.969 | EAR3-AILC | 0.476 | 0.120 | 1.713 | 3.042 |

| EAED1-EAED | 0.843 | 0.510 | 10.410 | 1.306 | EAED1-AILC | 0.587 | 0.230 | 3.450 | 1.495 |

| EAED2-EAED | 0.790 | 0.426 | 12.789 | 1.383 | EAED2-AILC | 0.485 | 0.141 | 2.648 | 1.450 |

| EAED3-EAED | 0.665 | 0.349 | 8.295 | 1.235 | EAED3-AILC | 0.401 | 0.112 | 2.292 | 1.322 |

| ICF1-ICF | 0.658 | 0.288 | 7.098 | 1.428 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ICF2-ICF | 0.825 | 0.383 | 10.812 | 1.701 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ICF3-ICF | 0.823 | 0.344 | 10.833 | 2.733 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ICF4-ICF | 0.789 | 0.268 | 8.659 | 2.623 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Second-Order Construct | First-Order Construct | Std. Beta | T-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEG (H1a) | ARF | 0.018 | 11.187 | 0.000 *** |

| MUAR | 0.026 | 1.453 | 0.186 | |

| GCR | 0.025 | 6.736 | 0.000 *** | |

| EOA | 0.020 | 8.537 | 0.000 *** | |

| API (H1b) | RNAS | 0.031 | 16.680 | 0.000 *** |

| MAR | 0.029 | 13.445 | 0.000 *** | |

| AAC | 0.028 | 11.352 | 0.000 *** | |

| AILC (H1d) | IAR | 0.042 | 18.555 | 0.000 *** |

| EAED | 0.055 | 5.624 | 0.000 *** |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std. Beta | T-Statistic | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1c | API -> AEG | −0.013 | 3.260 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H1e | AILC -> AEG | −0.050 | 2.892 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H2 | AEG -> ICF | −0.123 | 3.794 | 0.035 ** | Supported |

| H3a | API -> ICF | 0.100 | 2.866 | 0.030 ** | Supported |

| H3b | AILC -> ICF | 0.060 | 2.868 | 0.020 ** | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std. Beta | T-Statistic | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4a | FRC*API -> AEG | −0.017 | 2.571 | 0.010 ** | Supported |

| H4b | FRC*AILC -> AEG | −0.104 | 0.940 | 0.348 | Unsupported |

| H4c | FRC*API -> ICF | 0.049 | 2.280 | 0.038 ** | Supported |

| H4d | FRC*AILC -> ICF | 0.108 | 0.885 | 0.371 | Unsupported |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, F.; Akther, T. A Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Investigate the Audit Expectation Gap and Its Impact on Investor Confidence: Perspectives from a Developing Country. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205798

Xu F, Akther T. A Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Investigate the Audit Expectation Gap and Its Impact on Investor Confidence: Perspectives from a Developing Country. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205798

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Fengju, and Taslima Akther. 2019. "A Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Investigate the Audit Expectation Gap and Its Impact on Investor Confidence: Perspectives from a Developing Country" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205798

APA StyleXu, F., & Akther, T. (2019). A Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Investigate the Audit Expectation Gap and Its Impact on Investor Confidence: Perspectives from a Developing Country. Sustainability, 11(20), 5798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205798