Abstract

This article presents an analysis of the female working poor in relation to gender employment segregation. It draws a cross-national profile of the female working poor in Belgium and China: two different nations with distinct stories of socio-economic development and cultural heritage, while both are characterized by high female employment participation. Analyses show that (1) women share a higher proportion among the total working poor population in both nations during recent years, whereas (2) in-work poverty has been a chronic condition, particularly among female workers in low-quality jobs. Thus, to some extent, labor market institutions may shape this gendered tendency of in-work poverty. In this article, women’s position in the public sphere in relation to employment segregation is discussed, and a contextual analysis identifies the causes of gender employment segregation. The results shed light on the crucial role of gender employment segregations related to in-work poverty and show that gender ideology and stereotypes do matter in explaining such employment differences. We argue that the promotion of female participation should be combined with explicit measures to reduce the disadvantageous position of women in the labor market.

1. Introduction

Since the introduction of the Beveridgian paradigm [1], there has been a widespread belief that holding a job protects against the risk of poverty. Although the view that “most of the poor do not work” [2] lasted only until the early 1990s, the prevalence of “work first” employment strategies still assumes that working keeps people out of poverty [3,4,5]. Today, growing empirical evidence reveals that there is an increasingly growing group of workers having jobs but struggling to make ends meet: they are the “working poor”.

Social research widely stresses in-work poverty in industrialized countries [3,6]. Surprisingly, the Asian case is rarely the center of attention in this topic, and much less is known regarding the issue of the working poor in China. Furthermore, while early research shows that women suffer a significantly higher risk of poverty than men [7], looking at the working poor from a gender perspective is still uncommon. Most existing studies investigated the working poor through household-based measures of income or consumption (e.g., in Europe). This means that while poverty is often economically assessed at the household level, the issues of women’s economic independence and unpaid domestic contribution may be hidden behind their household contexts. Nevertheless, the issue of in-work poverty could be gendered with regards to housework allocation, family care obligations, and employment segregation [8,9].

In this article, we complement current research in two ways. First, instead of focusing on internal differences between similar countries, we highlight common issues and similarities between two different countries. China is a crucial case during this comparative analysis. Like European nations, China is very influenced by global and transitional processes. It has become increasingly evident that the risk of poverty exists not only as the classic forms (e.g., absolute poverty, unemployment and material deprivation), but also develops in a new diverse way in the context of contemporary China, such as the social exclusion reflected in employment segregation, the conflicts between traditional family obligations and an individual’s career development, and the individual economic dependency issue for women, etc. China is thus also facing the in-work poverty issue. Substantially, China’s experience offers a perspective from a region that stretches beyond the in-work poverty study of the rich world, “upon which most of the current academic writing in America and Europe tend to focus” [10]. Whether in Belgium or China, we can build up a cross-national comparison to develop a new way of looking at each other when facing the same social issue.

Second, we sought to offer dynamic insights on in-work poverty seen from a gender dimension and observing gender employment segregation as well: we depict the role of gender employment segregation in shaping women’s status in occupant hierarchy. By developing a transnational dialogue, we aim at emphasizing the commonly problematic of in-work poverty for workers who are viewed as gendered actors. Rather than merely expressing inequality, gender plays an intricate role as an organizing principle whether in employment or poverty issues. In this topic related to women, employment and poverty, gender “acts on several levels in society, influencing individual lives, social institutions, and social organization generally” [11] (p. 61); this is the general perspective we use to address international and gendered variations of the in-work poverty issue.

2. Belgium and China: Two Distinct Forms of Female Working Poor in a Pluralistic Modernity

2.1. Two Distinct Forms According to a Country’s Level of Economic Development

In the research, we look at two different forms of gendered in-work poverty: (1) Female working poor in a highly industrialized society—Belgium. As one of the earliest countries to be industrialized on the continent of Europe, Belgium is a classical case, which went through the Industrial Revolution in the 1830s. Nowadays, Belgium is a developed country with an advanced high-income economy and relatively well-integrated social security system. In this Western European society, workers have experienced significant structural changes in the economic framework, e.g., the progressive process of agricultural decline and a knowledge-based service sector development. These features contribute to promote women’s participation in employment, but many women have low-quality jobs and face work-family conflicts. With this background, the gendered in-work poverty mirrors a series of industrial (or postindustrial) problems in a highly developed economy. (2) Female working poor in a developing country under social transition and rapid economic development—China. The Western mainstream discourse has accumulated rich materials for exploring the in-work poverty issue and has provided a reference for further research in this field. However, this conceptualization does not include female in-work poverty in the Chinese specific context. Different from Western society, China is a big developing oriental nation based on a long history of self-sufficient peasant economy; furthermore, with thousands of years of civilization history, China has cultivated its own strong system of compound culture and formed its atypical Eastern culture. In a developing country with the transition from an agricultural to an industrial society, many social problems are overlapping with ambiguous boundaries. In this context, the issue of female working poverty seems both more complicated and more challenging. It thus shows a specific profile of this kind of in-work poverty with its over-represented rural features; it reflects the issues socioeconomically related to both agricultural and industrial stages.

2.2. Two Distinct Types According to a Society’s Level of Pluralistic Modernity

The selection in Belgium and China is also a reflection of two spatial logics in the spread of poverty (and even misery) placed at the same time. One is the female in-work poverty in full urbanization. After having experienced rapid industrialization and urbanization, by 1870, most Belgians lived in cities and depended directly on industry or trade. Belgium has ancient industrial traditions with a large number of developed professional guilds and with social mutual assistance (or solidarity) as the core of a social spirit, which constitutes the foundation of Belgium’s well-developed social security in which people achieve quite high standards of living, life quality, and healthcare. On this basis, female working poverty reveals the severity of increasing social differentiation in the labor market and social welfare; this is our first form of in-work poverty. The other is the rural female poverty type in a “contradictory compressed modernization” in which both agricultural and industrial societies coexist. Indeed, despite the dramatic economic growth, the socioeconomic transformation is still in the process. China is an ancient agricultural country with a long history of land development and utilization. Land remains the core to understand the nature of Chinese social structure, and the Chinese social relationships based on this continue to shape the specificity of this type of female in-work poverty.

3. The Possibility of Comparison between Belgium and China

Due to two very different societies with respective various reorganizations and conceptualizations about the in-work poverty phenomenon, it seems difficult to conduct a cross-national comparison of this observed social fact between Belgium and China. Nevertheless, it is possible to regard a comparative study as “a cross-level analysis (also could be a cross-system or cross-time analysis) where variation within the unit could be explained by characteristics of the unit” [12] (p. 196). Explanation in comparative research based on two distinct social systems is possible “if and only if particular social systems observed in time and space are not viewed as finite conjunctions of constituent elements, but rather as residua of theoretical variables” [13] (p. 30). In this sense, both the two nations have a gender classification; have families, which are protecting networks; and have labor markets and governments, which have policies related to social inclusion and welfare protection. It is in this four-fold context, with their “unique” characteristics, that our comparative analysis of a common issue (in-work poverty) will take place, on the basis of the following four aspects:

(1) “Most Different Systems” Design (MDSD): scholars Teune and Przeworski proposed two classical distinct comparative analysis strategies. One is the “Most Different Systems” Design (MDSD): the comparison of cases that only share a certain political outcome to be explained, and explanatory factors are considered crucial to generating the outcome. The other one is the “Most Similar Systems” Design (MSSD): It seeks to identify “key features” that are different among similar countries, which account for the observed political outcome. MSSD follows an intersystemic “maximum” strategy, common features can be regarded as “controlled for”, and intersystemic differences are explanatory variables. Then, the number of common features is maximal, and the number of differences is minimal, being abstracted as the above “key features” [13]. By comparison, MDSD provides a cross-systemic strategy, which allows us to choose two or more systems that are fundamentally different. It is particularly suitable for the comparative study of a specific outcome that needs to be explained. In other words, if the certain social issue records no significant differences within the system, and it occurs in two distinct systems, system factors do matter and one has to explain the common issue by looking at the differences between the systems. In the case of Belgium and China, we adopt the MDSD strategy. We will examine two very different social systems (Belgium and China) that show “multiple forms” of female working poverty. One is the female in-work poverty in full urban transformation. The other is the rural female poverty type in a mixed condition in which both agricultural and industrial societies coexist simultaneously. Through the MDSD strategy, we are interested in finding out why the working poverty is gendered both in Belgium and China.

The goal of the comparison is to figure out what happened about the observed groups in the nature of two very different social systems, to explore the common explanatory patterns leading to the gendered in-work poverty trends, and also to properly abstract and name the “unique” factors in explaining the generation of its multiple forms—single working mothers suffer a higher risk of poverty, and rural women are over-represented among the female working poor in China. In this way, our cross-national comparative research tries to explain the gendered trend of in-work poverty at the level of distinct social systems.

(2) Conceptual equivalence: The central issue of operating an international comparison is how to construct an appropriate definition and relevant measurable indicators. In order to achieve comparability, a shared definition of the in-work poverty issue must be tackled as the primary step in the research. In-work poverty is a multifaceted problem [14], resulting from or shaped by multiple factors, and the nature of working poverty may differ across nations. The “measured” working poor population may also be very sensitive to the statistical definition adopted, especially when we compare the profile of the working poor groups at the cross-national level. In the research, I define in-work poverty on the basis of two aspects—earned income poverty and gender-specific high dependency risk.

(3) Comparison logic path: The comparison logic path can well clarify the scale of the comparison between Belgium and China. The logic path in the research is as follows: construction (constructing the definition, namely, the proper concepts of the female working poor and its relevant dimensions, and on this basis, figuring out the cross-national profile of the working poor and their characteristics); comparison (based on gender employment segregation—reconstruction of the phenomenon (common and different factors are “redefined” in a tentative explanation)). We use the term “nation”, not only because it is the concept commonly used in international comparative studies [15], but also, and mainly, because we will refer to political, economic and sociocultural national systems.

(4) Poverty among workers: the research objective is the in-work poverty phenomenon, which adapts the core focus in the research: “poverty among workers” rather than “workers in poverty”. This special stress means that the working poor is primarily a subtopic belonging to the poverty issue based on the global anti-poverty cooperation, including the Chinese context into the international dialogue. The goal of improving citizens’ well-being is the same in all nations, but the ways in which this goal is pursued varies [16]. Thus, the measurement and exploration of poverty has become an international concern, even if many decades were required to develop equivalent and appropriate indicators that could be widely applied. Focusing on “poverty among workers” also reflects a growing attention to observing the poverty issue in work (among employed people). It further addresses the exploration of potential relationships between “poverty” and “work”; the “working poor” and “in-work poverty” are thus used interchangeably. The adapted understanding of the comparative objective makes the research more applicable and acceptable in the two common national settings: labor markets. Based on this, the research is dedicated to focusing on gender employment segregation.

4. In-Work Poverty as an Analytical Focus

4.1. Women, Poverty, and Employment

Since World War II, women’s participation in the labor market has steadily increased, but many of them were and still are trapped into occupational segregated “ghettos” due to growing demands for cheap labor [17]. This article aims to explore the link between in-work poverty and women’s position in the labor market. Concretely, we seek answers to the following two questions: Does the increase in female employment participation reduce the risk of women falling into working poverty? If the answer is no, we then ask: how can we evaluate women’s position in employment segregation? To address these answers, we elaborate on the large body of relevant research and investigate the gender segregation separately in the Belgian and Chinese labor markets at the occupational level.

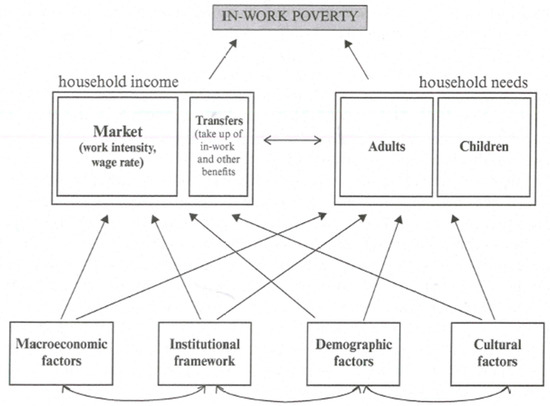

4.2. Crettaz’s Model of In-Work Poverty

Previous literature has presented an essential source for defining, measuring and describing this poverty issue [5,10,18,19,20]. Here, we employ Crettaz’s model of in-work poverty to help better understand the research perspectives and dimensions we integrate into the research framework (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Crettaz’s model: A micro–macro model of in-work poverty. Source: Lohmann, H., & Marx, I. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook on In-Work Poverty. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 51.

We regard in-work poverty as a double-level construction. The first level implies the individual dimension in terms of his/her position in the labor market. Previous empirical research demonstrated that the numbers of workers in low-income and non-regular jobs are significantly increasing in the labor market, and at the same time, in-work poverty is widely considered as a phenomenon related to the growth of this kind of insecure employment in the service sector [18]. The second level includes the family dimension used to measure poverty. The majority of research takes a household approach to the definition and measurement of the working poor (the second definition addresses its basis on the household-related poverty threshold (equivalized household income being under 50% or 60% of the national median income).) Crettaz’s model combines an individual’s status in the labor market with his/her household context. Both the individual and labor market levels contribute to the rise of in-work poverty. In particular, some research has offered evidence that the risk of in-work poverty generally decreases for men and increases for women across their life course. Behind this, a lot of factors may partially explain this gender difference. (The variations of these factors could also contribute to shaping the cross-national profile of gendered in-work poverty in different structures and welfare institutional contexts, and these cultural and instructional factors could be examined in a cross-national comparative framework.) We try to go beyond common macro-level factors to study in-work poverty by addressing women’s role in employment and cultural contexts. Trying to combine class, status groups and gender, my mentioned dimensional approach is, in a way, a step towards an intersectional analysis.

4.3. Theoretical Framework

In-work poverty as a global issue. In-work poverty does not occur by accident; it reflects the impact of globalization on local and national sustainability and stability.

As mentioned above, a number of socioeconomic trends have transformed societies since the 1970s [21,22,23]. Under the term “globalization” or the circumstance of an alleged “community of common destiny”, the world’s social and economic development has been an “emphatic turn towards neoliberalism” since then [22], and the economic configuration and the international division of work have undergone seemingly homogenous changes. This process has compressed the rise of economic and political globalization in both time and space (in Harvey’s viewpoint, China’s economic reform in 1978 is, in fact, an implementation of neo-liberal reform, and today China is still the critical actor in developing the above process) and also, it has entailed adjustments and even challenges for the patterns of family living, the gendered division of labor, social relations, and welfare provisions, etc. It holds that “the social good will be maximized by maximizing the reach and frequency of market transactions, and it seeks to bring all human actions into the domain of the market” [22]. As a result of this dominance of such market “belief”, it has produced an intensive tension in which relationships between individual, social/collective organization, and the welfare state have become increasingly complex within these transformations. Structures of social risk, meanwhile, have changed since then, and current social risks include precarious employment, wage insecurity, being working poor, single parenthood, or inability to reconcile work and family life [21]. In-work poverty, as a multifaceted issue, emphasizes that the nature of “work” itself has become more complicated, working types have become more diversified, and working conditions more precarious. How this kind of change has affected the relationship between poverty and work is probably best explained by Paugam’s (2017) “disqualifying poverty”, as more and more people are becoming involved in such a process of being disqualifying in the turn of socio-economic development with increasing precariousness, namely uncertain circumstances that are beyond one’s control. Furthermore, the evidence strongly suggests that this turn is “in some way and to some degree associated with the restoration or reconstruction of the power of economic elites” [22]. Linked to the above transnational processes, therefore, the in-work poverty phenomenon is not unique to a certain regional level.

Working poor in the labor market. In-work poverty research on middle-level theory involves labor market segmentation theory and social stratification, particularly in the occupational hierarchy [24,25].

Seccombe and Amey (1995) pointed out that social stratification is operationalized in occupational earnings, prestige or even wealth distribution. The working poor have undoubtedly faced unequal distribution in the labor market. This article thereby follows the conceptualization of Rupured (2000), who describes the working poor as “individuals who work at least part of the year and earn less than a given percentage of the federal poverty line” [26]. Some scholars like Rupured (2000) regarded it as a community issue, and a relevant definition has been put forward that the working poor belong to the “lower class as workers who earn current dollars are below cutoff which adjusted the overt time for inflation” [27] (p1144). Some research addressed the idea that the working poor does not only belong to the middle-class: the “welfare state enables the middle-class to develop and maintain assets through institutional arrangement, and working poor are more vulnerable to increasing deprivation” [28] (p57). More people who work in a lower level of the occupational hierarchy are observed in relevant research, such as workers in agriculture, service and manufacturing sectors [29,30,31].

The gendered tendency of in-work poverty. One stream of research focuses on the extent of in-work poverty, and the question of who experiences it. These authors revealed the gender dimension of in-work poverty.

Around 2000, the feminist analysis of working poor women was developed. An important debate about “the feminization of poverty” was put forward [17], in which there were mainly two viewpoints: (1) The multi-roles collide. According to a report by the International Labor Organization (ILO), women at the workplace face inequalities in aspects of hiring, promotion standards, access to training and retraining; in the family field, even women in higher-level jobs in developing countries spend 31–42 h per week in unpaid domestic activities [32]. Society shapes multi-roles for women: employee, mother, daughter, and family provider. Furthermore, sometimes such roles are constrained both in public and private spaces if the state or employer does not provide a specific policy or service to balance it. (2) Disadvantaged position in the social structure. Certain studies stressed the appearance of women-focused trends in the labor market, in family structure, occupational segregation, and welfare systems that tend to push women into poverty. De Wolff (2000) observed working poor women in Canada, pointing out that in the face of globalization and flexibility, poverty impacts more on women than men in labor markets. Throughout the decades, government programs have contributed to the creation of a more "flexible" labor force, and “women have done more precarious work than men throughout most of the century” [33]. Otherwise, Gilbert (2000) researched working poor women’s survival strategies, finding that it is the institutionalized and racists in the housing and labor markets that affect how women fulfill their multi-roles. In a gender dimension, research on the female working poor needs to pay attention to both public and private spaces, to understand how these two spheres occupy a role in in-work poverty.

5. Research Contextualization and Methods

We hypothesize gendered in-work poverty to be associated with one of the following three factors. First, the economic environment and the labor market. If someone is employed in a low-quality job with low earnings or unstable part-time hours, this leads to a high risk of flexible and insecure conditions. Thus, although low pay may not be the only reason for in-work poverty, being in low-paid employment is found to raise the risk of being economically poor [18,34]. Second, individual qualifications, that is, the lower educational attainment level or lower skill, may impact profoundly on a worker’s position and earnings. Third, the differences in in-work poverty across nations can be partially contributed to by the interplay of labor markets and welfare state institutions, which include here the employment-oriented policy and family-friendly policy in the labor market and public services provisions, as well as the gender occupational segregation and the gender employment gap [10]. We integrate the gender approach with perspectives of employment segregation. The comparison unfolds in three sections:

The first section begins with a picture of in-work poverty in Belgium and China.

The second section analyzes the working poverty from a gender perspective, focusing specifically on women’s position in the public sphere in relation to employment segregation.

The third section explores the causes of gender employment segregation, and explains possible processes affecting the gendered tendency of in-work poverty.

With a particular focus on women’s role in labor markets, the research is rooted in the tradition of international comparative welfare analysis, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data. Concerning the problem of potential access to data and inconsistencies in the available information, we adopt their respective measurements by relying on official definitions of poverty and workers. We draw the Belgium data mainly from Eurostat—Labor Force Surveys statistics (LFS) and Income and Living Conditions (SILC), and adopt national data from The National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) and Chinese general social survey (CGSS) in China for mapping the working poor population (Appendix A). In addition, we adopt multiple methods in comparative case studies, which principally cover qualitative analysis with a political focus, and build a link to sociocultural and historical interpretations complemented by quantitative data descriptions. This mixed-methods perspective will be helpful to generate insights capable of presenting a relatively integrated picture of in-work poverty, and to gain a deeper understanding of its complicated nature in various “social spaces” (household, gender, and labor market) and a cross-national context. We draw this cross-national profile on the basis of relevant national data collection (to know “less about more”: describe similarities and differences between characteristics), and next, by comparing and reconstructing this specific issue in employment segregation (to know “more about less”: in-depth exploration of multiple explanations [35].

6. A Cross-National Profile of the Female Working Poor

Belgium and China, the two case studies, are relevant to debates regarding women in in-work poverty. China is a fairly typical case, as it is a nation facing both a high female labor force participation and relatively high gender inequality in the workforce. Women’s employment in China ranks as one of the highest in the world, with a female labor force participation rate of 63.3 per cent in 2016 [36]. Meanwhile, in-work poverty in China affected 13.6 per cent of employed persons in 2013 (Table 1). Women have suffered more disadvantages than men in aspects of employment, payment, and retirement age since the 1978 economic reform and market transition [37,38,39]. With regards to wage equality, according to the Global Gender Gap Report (2016), women in China earn on average 35 per cent less than men for similar work, ranking in the bottom third of the Global Gender Gap Index. Moreover, in terms of occupation level, women in China show relatively weak empowerment, with a female/male ratio of 0.20 in positions of legislators, senior officials, and managers [40].

Table 1.

In-work poverty rate for employed persons, China 1986, 1997, and 2013.

This trend is not unique to China, as it also happens in some European nations. Since the late 1990s, European countries started to focus on this poverty issue among the employed population, and “in-work poverty” was put on the EU policy agenda in the 2000s. In 2003, a new indicator measuring the working poor was added into the European Employment Strategy (EES) and the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) on poverty and social exclusion: In-work at-risk-of-poverty, which officially defined the European indicator for monitoring the working poor in the political program of employment strategy and social inclusion. The currently launched policy strategy of “making work pay” also reflects the prevalence of income inequality among active populations in most European countries (Appendix B).

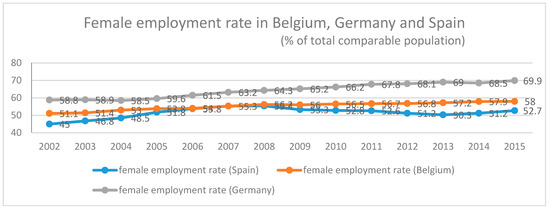

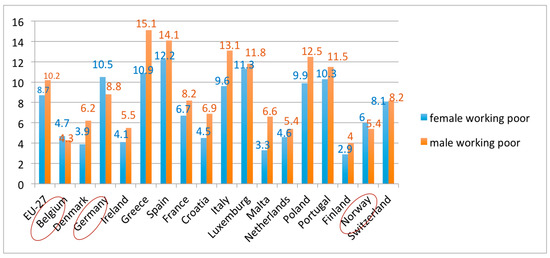

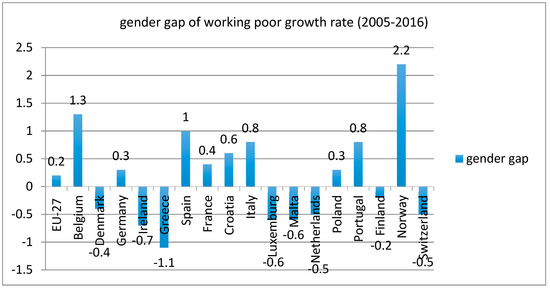

Belgium, which could be viewed as a representative of the European Union, also faces the same gendered poverty issue as China. As seen in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, while Belgium shows relatively higher female participation in the labor market and a relatively low in-work poverty rate at the EU level, women suffer a higher risk of in-work poverty than men. Europe shows a common phenomenon that men usually suffer a higher risk of working poverty than women in the labor market (EU27 in 2015: male 10.2% > female 8.7%). First, while a majority of nations demonstrate this similar tendency at the EU level, some nations do not. For instance, Germany, Belgium, and Norway all record a higher in-work poverty rate for women than for men. Second, the gender gap of working poor growth rate challenges this general claim, and Figure 3 indicates that more than half of the EU nations experience a higher growth rate for women. In Table 2, while there has been a slight decrease in female in-work poverty in Belgium since 2014, over the last decade (since 2010), female in-work poverty has been slowly growing. Concretely, the gender gap has been on the rise during the 2010s, and the grow rate of in-work poverty for women is higher than that for men. In this sense, Belgium is likely to experience an over-represented and growing trend in the female working poor during recent decades.

Figure 1.

Evolution of female employment rate (%) for total comparable population, in Belgium, Germany and Spain, 2002–2015. Source: Eurostat. Employment rates by sex, age and citizenship (%) (lfsa_ergan).

Figure 2.

In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate by sex in European countries (age from 15–64) (2015). Source: Eurostat. Employment rates by sex, age and citizenship (%) (lfsa_ergan).

Figure 3.

Gender gap of working poor growth rate between 2005 and 2016 (female growth rate–male growth rate). Source: calculated according to the Eurostat.

Table 2.

In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate for employed persons (age: 18–64), by sex, Belgium 2005–2016.

Concluding this section, we can find that Belgium and China are both prominent sites in the gender trends of in-work poverty over recent decades. In both cases, women share a higher proportion among the working poor during recent years; also, the female working poor recently record a gradually increasing tendency in Belgium and China. Based on the above, the increase in female employment participation does not reduce the risk of women falling into working poverty.

7. Descriptive Analyses: Gender Employment Segregation in Belgium and China

The first question has been well answered, so how can we evaluate women’s roles in employment segregation based on a gender perspective? With a focus on Belgium and China, we highlight their divergent gender segregations and women’s position at work.

7.1. Occupational Gender Segregation in Belgium

Figure 4 and Table 3 present the female employment proportion by professional status in 2015. In Belgium, three patterns stand out. First, the proportion of women in management status is approximately 32.8 per cent. Women make up nearly 49.6 per cent of workers at lower levels of management, compared with 23.5 per cent of self-employed workers at higher levels of management and 33 per cent of workers at higher levels of management. This means that, in senior sectors, women are under-represented and tend to focus on a lower managerial level. Second, women’s employment faces the segregation trend of being over-represented as clerical support workers (women, 63.7%), while men share a higher proportion of managers. Third, among professional sectors, female workers were classified into the trend of middle-lower professional status. Women account for 54.8 per cent among the professional sector, the majority of which was concentrated in associated professionals, particularly in the health and teaching professional sectors. Among the high level of professional sectors, such as in science, engineering and information and communications technology professionals, women only account for 22.1 per cent in Belgium.

Figure 4.

Female employment proportion by professional status in 2015 (%). Source: Own calculations using the Eurostat, LFS series. Employment by sex, age, professional status and occupation - (lfsa_egais).

Table 3.

Female proportion within professional sectors in Belgium (2015).

Figure 5 shows the female proportion by socio-economic groups for Belgium in 2015. Women account for more than 63 per cent among lower status employees. Within lower socio-economic groups, about 90.9 per cent of cleaners and helpers and services employees in elementary occupations are women.

Figure 5.

Female proportion by socioeconomic groups in Belgium (2015).

Figure 6 presents the employment proportion by work-type and professional skills for Belgium in 2015. Women’s employment is related to a slightly higher segregation trend in part-time jobs, and about 79.7 per cent of part-time workers are women. Among full-time workers, women share a greater proportion in elementary occupations (women, 63 per cent) and services and sales work (women, 68.1 per cent).

Figure 6.

Employment proportion by full-time/par-time and professional skills in Belgium 2015.

By breaking down the variance in the employment rates of men and women in different professional statuses and socio-economic groups, we argue that women in Belgium seem to be employed in a disadvantaged location of economic decision-making positions, and also, employment rates are relatively highly segregated among lower status and especially low-skilled employment.

7.2. Hierarchical Gender Segregation in Mainland China

Gender-based employment segregation in China mainly manifests as hierarchical segregation, and it stands for occupation-specific ladders. Different societies have different social strata, and the social classification may change in various social development stages. Since Reforming and Opening, the Chinese former social classification of “two classes, one stratum” (worker class, peasant class and intelligentsia stratum) has been already divided into various new classes, e.g., manager class, office clerks, etc. Then, the society is divided into ten major social classes and five social hierarchies (Appendix A), which is based on the occupational-specific ladder and the possession of three kinds of resources (organizational resources, economic resources, and cultural resources) (It reports the ten social classes from the top down: (1) national and community managers; (2) managers; (3) owners of private enterprises; (4) professional technicians; (5) affairs-handling personnel (office clerks); (6) privately or individually-owned businesses; (7) business services staff; (8) industrial workers; (9) agricultural workers; and (10) rural and urban unemployment or under-employment. The five social hierarchies are, respectively: upper class, upper-middle class, middle class, lower-middle class and under class.). Organizational resources are the most decisive resources within the three kinds, as the special institutional arrangement for social class differentiation still has a significant impact. The country has a substantial role in the allocation of resources; the ruling party and government organization are controlling the most important and a lot of resources in the whole society. Since the 1980s, economic resources have become more and more important, but the power is suppressing the growth of wealth. Meanwhile, cultural resources have become more significant in the past 10 years.

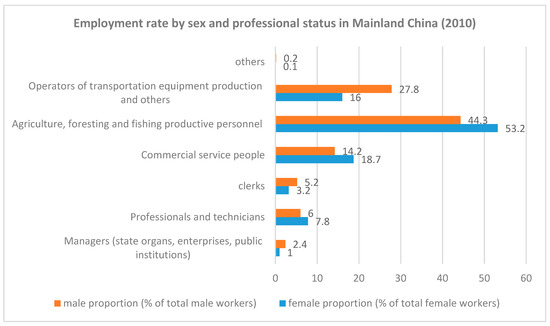

In this regard, we focus gender segregation on the six most common occupations in Mainland China. Figure 7 presents the gender proportion according to occupational status in 2010. Women record a significantly much lower proportion than men among total managers, showing the weakening disadvantages of possession of resources allocation by those in power in the upper class. Among professionals and technicians, women have equal shares in proportion to men, which may mask the fact of the possession of relatively equal education, skills and culture resources for women in the middle class. However, women share a higher proportion among health and teaching professionals, and the sector of scientists and technicians operates based on male-dominated segregation (women, 39.8 per cent; men, 60.2 per cent).

Figure 7.

Employment rate by sex and professional status in Mainland China (2010).

Figure 8 underlines the fact that most people work and live in the middle and lower classes. The agricultural production sector has a large number of male and female workers. In terms of the gender dimension, women show a feminization tendency in agriculture. More than half (53.2%) of workers are women among agricultural and fisheries production workers, with a higher participation rate than men (8.9%). In higher socio-economic status, women make up only 25.1 per cent of managers.

Figure 8.

Employment rate by sex and professional status in Mainland China (2010).

The above two figures demonstrate that women work in the labor market with a lesser amount of power than men at the same occupational level. While there is indeed a significant increase in female employment, some occupational statuses with crucial organization and economic resources are not frequently women’s positions. Women face a trend of being over-represented in middle-lower socio-economic status and the feminization of agriculture. Many women work in lower professional status with less fame and prestige (e.g., female agriculture productive personnel in China), and the occupation status is segregated based on gender bias. Therefore, as there is a lack of enough seats in economic and political decision-making, female workers remain silent and their interests and needs are muted to some significant extent; at the least, the upper, and upper-middle classes are gendered with male domination. In addition, women are particularly at high risk of in-work poverty because poverty in China is concentrated in rural areas, where women are disproportionately employed in agriculture.

7.3. The Differences and Similarities in Women’s Employment in the Two Nations

There are considerable differences between Belgium and China in women’s employment. China is still in the transition process from agriculture to industry; even though the tertiary industry is developing quickly, based on a large population base, the agriculture industry still accounts for a large proportion. Over 44 per cent of men and 53 per cent of women in work are in the sector of “Agriculture, foresting and fishing productive personnel”, reflecting the importance of agriculture in China. There is a large number of workers in the primary industry, and women are no exception. In China, more than 50 per cent of female workers worked in villages and were employed in the agriculture industry, with about 49.2 per cent and 44.0 per cent of women, separately, working in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector and in manufacturing (while such rates are only 28.2 per cent and 23.5 per cent in Belgium). This means that women’s employment is highly concentrated in the primary industry with a feminization tendency in agriculture.

Table 4 shows women’s employment in the top feminized jobs. The top four feminized jobs in China belong to relatively low-paid jobs, such as care workers and family service personnel (89.2 per cent), sanitation workers (71.6 per cent) and textile employees. In contrast, the tertiary industry shares a significant portion in Belgium, and most women work in tertiary sectors; for example, women are, with nearly 40 per cent, highly represented in public service sectors (e.g., education, human health, and social work activities). Belgian women are highly segregated into vital service sectors such as personal care (95.0 per cent), cleaners (90.0 per cent), and customer services clerks (71.9 per cent). Also, part-time jobs in Belgium are highly segregated based on being female dominated.

Table 4.

Women’s employment in top feminized jobs in Belgium and China.

While the Belgian and Chinese labor markets are in different stages of development, women seem to be over- or under-represented in specific employment sectors, in which some common tendencies can be analyzed in-depth. Women in both the two countries face a disadvantaged occupational segregation across higher-income level jobs, through being under-represented in professional, scientific and technical activities, financial services, or as managers, scientists or engineers. Concerning professional status, there are over 60 per cent of men among those working as managers in both the two countries. However, women within this employment level show relatively lower proportions in both two nations. Moreover, the data mask the fact that there are increased numbers of women working in segregated traditional service sectors, such as health services, social work services, and accommodation and food service activities, which are also well known as medium-lower paid jobs. Furthermore, the inequality gender segregation across economic sectors and fields of science persists, in which women share a significantly lesser proportion. Separately, in Belgium, female workers share a significantly higher proportion in education and public services sectors (i.e., human health and social work services). Meanwhile in China, the female–male ratio differences are not so significant, but women shared almost half the proportion in primary industry, such as the agriculture and manufacturing sectors (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Women proportion within sectors in Belgium and China. Source: Own calculations using Belgium data: Eurostat-LSF (2015) and China data: 2010 people census of China.

In detail, by looking at the gender proportion by high-paid/low-paid occupations, according to the classification of crucial resources (organization, cultural and economic resources), we select teaching, management and IT technicians in high-paid occupations, and care workers and cleaners who are always at the bottom of relatively low-wage ladders (Table 5).

Table 5.

Gender proportion by sex and high-paid/low-paid occupations in Belgium (2010) and China (2015).

(A) High-paid occupations (teaching, management, IT)

Teaching professionals seem to be a relatively highly feminized occupation in both the two countries (Belgium, 70.8 per cent; China, 57 per cent). Professoriates are among the highest-paid and most prestigious working groups in the profession, with a relatively high proportion of women (51.7 per cent in Belgium and 49.4 per cent in China). Hierarchy segregation among teaching professionals affects women’s employment weakly. Unlike education, in Belgium and China, management is still dominated by men (Belgium, 32.8%; China, 25.1%). Women make up only 30.6 percent of senior decision-making bodies in the Belgian government and large companies, and only 22.7 percent in China. The under-representation of women among managers within organizations confirms the difficult access for females and gender discrimination to some degree. Moreover, another high-paid occupation is IT technicians, which increased fast during the last two decades both in Belgium and China. Meanwhile, according to the author’s own calculation using Eurostat, Belgian women only account for 12.3 per cent among IT technicians, and in China, women account for less than 25 per cent. There are more male employees in IT, and it stems from the educational choices of young girls and boys, which directly affect hiring trends.

(B) Low-paid occupations (care workers, cleaners)

Care workers are characterized as highly feminized and relatively low-paid, with the share of women among care workers reaching a high 95 per cent in Belgium and more than 89 per cent in China, and male care workers being rare. The daily routines of care work such as cooking, house-cleaning and bathing, taking medicine, or shopping are regarded as the usual domestic work in private spaces; the stereotypes for women’s housework expand to the labor market, and with relatively low pay, women dominate in care work. Cleaners seem to be the bottom of the occupational and pay ladder, and both Belgium and China share higher proportions of women.

Therefore, in high-paid occupations, women’s employment in education fields seems advanced, sharing equal opportunities to hold cultural resources. However, women still face relative disadvantages in employment among managers and IT technicians, revealing the obstacles to power and economic resources. What is more, concerning low-paid occupations, women in both the two countries share high counts in traditionally feminized occupations. The study finds that the top feminized jobs in Belgium and China seem to be closely related to less educated demand and low salaries, and the significant gender segregation in management and in professional, scientific and technical activities, associated with higher pay and resources, indeed limits the access to entry and promotion for women. Bettio (1984) argues that occupational segregation often confines women to lower value-added, lower-paid jobs. In fact, this kind of occupational segregation shapes the much greater risk into poverty for women.

8. Explanatory Analysis: Main Causes of Gender Employment Segregation

In Belgium and China, both labor markets show gender gaps significantly in the employment of occupations, thus forming male-dominated and feminized jobs in occupations and even in hierarchy ladders. We focus here on the perspectives of biology, under-investment, and stereotypes to understand how gender employment segregations are formed in the two nations.

8.1. Biology

As for the gendered division of labor, biology (biology here emphasizes a variety of physical differences between men and women, such as muscular power versus resilience or dexterity) is perhaps the oldest explanation. Based on comparative biological advantages, the studies since the early 1970s have shown that women are good at handling verbal competence and men are better at solving abstract mathematical and visual–spatial problems, which supports the explanation of lower female proportions in mechanized and labor-intensive jobs. Nevertheless, women in Belgium and China show a much lower proportion in manufacturing and construction sectors. Physical characteristics became less important following technological progress, and brain or mind work has become the mainstream among almost sectors. Thus, biology plays quite a limited role in explanation for Belgium and China, especially to analyze the significantly under-represented employment for women in professional, scientific and technical activities.

8.2. Under-Investment

Much attention has been paid to the fact that education and training skills may be primarily and directly associated with occupational choice. Under the perspective of human capital theory, some scholars think that the feminized jobs related to low skills and low pay are mainly caused by under-investment in education or training for women, which means that the formal education gap between men and women mainly leads to the gender employment gap within the tertiary sector.

Figure 10 reports the proportion of workers by sex and educational attainment level for China in 2010. While the general education attainment levels both for male and female workers are generally low, on average, women receive fewer education years than men (women, 7.9 years; men, 8.7 years). According to the sixth nationwide population census, when looking at the male–female ratio in the same education level, we find that female workers generally share a lesser proportion, especially in middle-higher education level, than male workers. Also, in the high education level, female workers shared a slightly lesser proportion than male workers in China.

Figure 10.

Percentage of workers by sex and educational attainment level in China (2010). Source: own calculation using the sixth people census of China.

Figure 11 shows that women account for 42.9 per cent at the undergraduate college level, which is 14.2 per cent less than male workers. At the graduate student level, women only account for 39.5 per cent. Thus, women in China show slightly fewer average education years than men, which is related to disadvantaged positions in the same education level. Especially in the secondary and tertiary education levels, female workers show a lesser proportion than male workers. Thereby, women’s participation in various occupations in the Chinese labor market can also be viewed as a reflection of educational segregation, which means that the main explanation for such gender segregation is revolved around education. The under-investment factor can explain partially the middle-lower status for women’s employment in China. As for large numbers of low-educated women, they more easily access occupations where less education/skills are needed, and the salary will not be so high in these jobs. Based on this, job training and education promotion are still quite important and efficient for female workers.

Figure 11.

Gender proportion by educational attainment level in China (2010). Source: own calculation using the sixth people census of China.

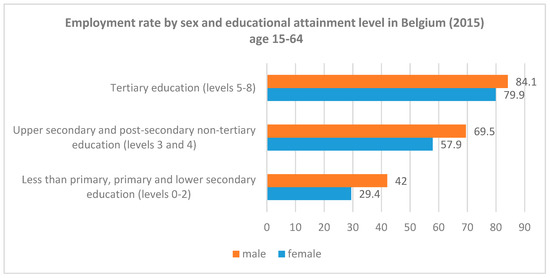

Under-investment does not work to explain the Belgian case. Figure 12 presents the percentage of workers by sex and educational attainment level for Belgium in 2015. Large numbers of male and female workers have relatively high educational attainment levels. Among female workers, there is more than 49.8 per cent of women who have attained tertiary education levels, which is relatively higher than males at the same education level. Otherwise, when looking at the employment rate by sex and education level, the female employment rate in every education level is generally lower than that for men.

Figure 12.

Percentage of workers by sex and educational attainment level in Belgium (2015). Source: Own calculation using Eurostat- lfsi_educ_a.

Figure 13 shows employment rates by sex and educational attainment level in Belgium. There is 29.4 per cent of women at levels 0–2 who are employed, which is much lower, by 12.6 per cent, than men. At the high education levels 5–8, there is 79.9 per cent of women in this high education level employed in the labor market, which is still lower than men (84.1 per cent). Obviously, in the Belgian labor market, women workers show a positive trend of having relatively middle-high education attainment level; more than 49 per cent of them have attained a high education level, which is higher than that among male workers. However, at the same education attainment levels, women show a relatively lower employment rate than men, no matter in lower or higher levels. Thus, it seems that, at least for Belgium over the past 10 years, the influence of under-investment on the gender segregation in the labor market was quite weak.

Figure 13.

Employment rates by sex and educational attainment level in Belgium (2015, age: 15–64). Source: own calculation using Eurostat: lfsi_educ_b.

8.3. Obdurate Nature of Gender Ideology

Gender ideology, especially stereotypes of personal qualification, creates the oppositions of labor division both in private and public spaces. This kind of opposition reflects the conservative attitude of the male-breadwinner model in relation to women that remains in Catholic families and in traditional Chinese clans. In fact, such ideology formed by societies shapes the divided relations between men and women in various aspects, such as gendered social attitudes, allocation of housework or care obligations, dealing with public affairs, and even women’s development in professional careers.

Even though there exists the cultural difference between the West and East, surprisingly, the lower female employment rates at motherhood and retirement age still rely on the traditional male-breadwinner model in both two countries. One possible explanation is that occupational segregation in the labor market may be based on the gendered nature of labor division; the point is that the division of labor is of a gender-based nature rather than respecting nature itself. Presumptions about women being more appropriate for domestic work indeed happen in both cultures, and “women caring at home, men working outside” has been historically the common social traditional norm in Belgium and China. In other words, we could use the word “domination” to describe the impact of this kind of stereotypical contrast of gendered labor division in households and employment. Even until recently, for example, mothers with early aged children are not expected to work full-time and take frequent business travel, while men as fathers seem to be exceptions to this idea on most occasions. Being identified as “late-comers” in the labor market, especially in occupations with sources of higher pay and prestige, women suffer more stresses and their conditions are profoundly influenced by these gender-shaped ideas, and such stereotypes about female workers are closely linked to women’s general performance in domestic work at home. Based on this, women are good at teaching, caring people and cleaning, while men already gain rich experiences about research, business and so on, which forms invisible barriers preventing women from entering specific male-dominated occupations, such as the scientific sector and investigation field traditionally dominated by male culture. This can clarify why feminized jobs are closely related to cleaning, caring, customer service and so forth, and why women share a lesser proportion in scientific and technician fields while being over-represented in employment in service occupations. In Belgium, for instance, even though Belgian women reached a relatively equal educational attainment level to men, the lower-status occupations, which are characterized as low-skill and service-oriented, are over-represented by women. Obviously, such an obdurate nature of ideologies enforces different treatments of men and women in labor markets.

Additionally, there are two interesting phenomena separately in the two countries. Firstly, under the refined formal childcare and eldercare system, Belgian women still apparently spend more hours than men in domestic work and less working hours in the labor market, and women are over-represented in employment in part-time jobs. Secondly, in China, women work overtime like men in the labor market, and also spend significantly much more time in unpaid domestic work. In fact, although being located in relatively less disadvantaged economic positions, most female working poor tend to take the family as the priority, and value themselves through playing crucial roles (e.g., caregiver, housewife) in the family field more than through development in their career. Most of them are employed in lower-status so-called feminized jobs, not because they do not care about the low income, but just because they have a demand for flexible time to balance work and family. The above two cases point to continued gender inequality in employment and highlight the role that ideology plays in these outcomes. Indeed, observing women and family policies, fertility is one of the main considerations impacting on the development of family policies and the adjustment of relevant family benefits: through proposing various relatively generous programs of family allowance to encourage childbirth in Belgium; or launching a family-planning policy with a single child family award to control childbirth in China. The promotion of family benefits does not purely serve to provide the person’s well-being limited to the family field, it is one part of the socio-economic political framework, which combines the accomplishment of other tasks in the market as well. On this basis, the generous family allowance based on the numbers of children and flexible family-work balance policies in Belgium functions well in adjusting the supply of labor increase. Similarly, the change of fertility policy (open two-child policy) since 2015 and the cancellation of single child family benefits in China can be useful to cope with the rapid ageing issue and the gradually diminishing “demographic dividend” in the long run. On most occasions among the above family policies, women receive family benefits as the role of a life-giver or a caregiver in which the “classic” gendered division of labor is more considered and women’s reproductive function is still more valued than their productive function. Among a series of corresponding provisions—such as birth grants, maternity leave, early childcare/childcare, motherhood help, etc.—child benefits are the core of family allowances. On this premise, women’s interests/needs are established in advance depending on their relationship to other family members, which is not defined on the basis of women’s own choices. In fact, it is hard for women to choose under such a political environment in which the defined relationship exists before women’s self-recognition.

Overall, when the women’s share in occupations is higher or lower than the expected accounts based on the same personal qualities (education, skills, time distribution, etc.) compared to men, gender, in relation to the education system and the family circle, does matter in explaining such employment difference. So, the form of feminized jobs in both the two countries is influenced by these presumptions originally from the gendered nature of labor division, to some extent.

9. Conclusions

The results invite us to consider how the gendered tendency of in-work poverty evolves and how this relates to women’s position in the labor market. With regards to the gendered trend in light of the realities in China and Belgium, the female working poor’s fate is not entirely and primarily determined by “the chance of using goods or services for themselves on the market” in Weber’s terms of “class” [41]. We observed that this gendered in-work poverty exhibits two prominent issues in both nations: women are over-represented in low-quality jobs according to the employment situation; and gender ideology behind employment segregation. This implies the generic connotation of the “female working poor”: the kind of positions (or statuses) in the market and society is the decisive moment that presents a common condition for the female working poor’s fate. In this sense, the “group situation” may be the de facto “status situation”, and the female working poor is a “status group”.

Additionally, as the social risk has become more varied and unpredictable, having work (especially low-quality jobs) becomes a more fragile linkage with a person’s social rights and relevant social security. In this regard, we suggest drawing attention to the gender dimension and specific national case. For women in Belgium, there are increased numbers of women working in low-income jobs, and their marital status experiences the trend of instability. In China, more than half of women are working in agriculture and low-skill service jobs in tertiary industries, and they are carrying the burden of heavy family caring responsibilities. A gender analysis of poverty examines the interaction of socioeconomic relations with the features of the family, labor market and the welfare state. Taking off from this viewpoint, the analyses not only understand gendered working conditions in the labor market, such as the gender pay gap and gender employment segregation, but also should be interconnected with the gender disparity of housework allocation. In this sense, poverty could be measured at an individual level of status or wealth. Similarly, we suggest that in-work poverty could be understood in relative terms of the individual’s status in the labor market hierarchy. With this, the article attempts to contribute to focusing on women with their low employment situation (low pay, part-time work, etc.).

In China and the EU, it is becoming ever more clear that a new approach is needed to combine the promotion of women’s participation with explicit measures for reducing the disadvantageous position of women in the labor market, to anchor well-being and gender indicators in private and public policies in the 21st century. Indeed, national cultures and related family policies are interacting in a much more complex way that profoundly shapes women’s unfair labor participation in the labor market. As Johannes Willms said in the book Conversation with Ulrick Beck: “welfare is a matter of bads as well as goods” [42], and what we would take into account today is to see the “insufficient” parts in such a world risk society. Obviously, women suffer more challenges and uncertain freedoms than men in all age groups, and social and labor market policies should recognize this in a gender dimension.

Funding

This research was funded by the [Special fund project of basic scientific research of central universities in China] grant under [63192101].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. EU-SILC and The Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS)

Eurostat: The Statistical Office of the European Union (EU) situated in Luxembourg. Eurostat gathers data from the National Statistical Institutes (NSIs) across Europe and provides comparable and harmonized data for the EU to use in the definition, implementation, and analysis of EU policies [43]. EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC): an important database of Eurostat in the social field, which is an instrument anchored in the European Statistical System (ESS). It is the primary reference source for statistics on income, living conditions, and in particular, on poverty and social exclusion in the EU. EU-SILC covers three topics: people at risk of poverty or social exclusion, income distribution and monetary poverty, living conditions and material deprivation. Among them, it provides indicators concerning the in-work poverty topic with various dimensions: age group and sex, household type, work intensity of the household and household type, educational level (ISCED), working time, etc.

The Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS): an annual survey of Mainland China’s urban and rural households. Launched in 2003, CGSS is aimed at gathering longitudinal data on social trends and the changing relationship between social structure and Quality of life in China. Social structure refers to the dimensions of social groups and organization as well as networks of social relations. Quality of life is the objective and subjective aspects of people’s well-being, both at the individual and aggregate levels. The scope of CGSS contains employment, families, household composition, living conditions, social networks and social stratification.

So far, CGSS data have only been available until 2010, while EU-SILC’s 2015 women employment data were used because it was the year with the most comprehensive data available from EU nations.

Appendix B. Working Poor in Europe

Since the economic crises and recession, the European policy framework has gradually recognized the poverty issue closely related to social exclusion in employment, and this partially contains a gender perspective. On this basis, the working poor are being targeted in anti-poverty projects and programs step by step.

Preventing in-work poverty has been a part of the overall goal to reduce poverty in the EU. The turning point is the Europe 2020 strategy proposed by the European Commission, which sets the target of lifting at least 20 million people out of poverty, and poverty as a key indicator mainly measures the progress of achieving the goal. More specifically, The European Commission’s recommendation of 26 April 2017 on the European Pillar of Social Rights explicitly recognizes the need for policies through which in-work poverty shall be prevented (earlier in 2003, as part of the European Employment Strategy and the “open method of coordination” on poverty and social exclusion, the EU had explicitly called upon Member States to reduce in-work poverty). In general, the in-work poverty phenomenon addresses the negative impact of social exclusion in the labor market, and there has been a call for a series of initiatives within recent years, such as the Agenda for New Skills and Jobs Exclusion, which mentions labor market segmentation and insecurity; the new European Platform against Poverty and Social exclusion (2010), which calls for fighting in-work poverty; and the Joint Employment Report for 2010, which clearly revealed that a quarter of people who are experiencing poverty are employed. The European Social Fund (ESF) positively promotes the development of European nations as a uniform economic market in terms of job creation, anti-discrimination, and equal cohesion into the labor market. While a gender dimension has not yet been specifically addressed in anti-poverty initiatives among the working population, the gender equality in employment has been strengthened. The European Commission recently put forward the initiative of “A new start to address the challenges of work–life balance faced by working families” (2015). Through reforming work–life balance policies, the project helps toward a better balancing of caring and professional responsibilities for parents with children or those with dependent relatives, and to some extent, promotes women’s integration into economic spaces.

References

- Mead, W.H.B. Social Insurance and Allied Services; HMSO: Richmond, UK, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, L.M. The New Politics of Poverty: The Nonworking Poor in America; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén, A.M.; Palacios, R.G.; Peña-Casas, R.; Europeen, O.S. Earnings inequality and in-work poverty. In Quality of Work in the European Union: Concept, Data and Debates from a Transnational Perspective; PIE—P. Lang: Ixelles, Belgium, 2009; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Employment Outlook 2009; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Working Poverty in Europe; Fraser, N.; Gutiérrez, R.; Peña-Casas, R. (Eds.) Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crettaz, E. Fighting Working Poverty in Post-Industrial Economies: Causes, Trade-offs and Policy Solutions; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie, D.L.; Gorman, B.K. A gendered context of opportunity: Determinants of poverty across urban and rural labour markets. Sociol. Q. 1999, 40, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posel, D.; Rogan, M. Gendered trends in poverty in the post-apartheid period, 1997–2006. Dev. South. Afr. 2012, 29, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, F. The impact of austerity on women. Defence Welfar. 2015, 2, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann, H.; Marx, I. The different faces of in-work poverty across welfare state regimes. In The Working Poor in Europe: Employment, Poverty and Globalisation; Edward Elgar Pub: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, N.E. Gender, Work, and Family in a Chinese Economic Zone: Labouring in Paradise; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Teune, H. Comparative Research, Experimental Design, and the Comparative Method. Comp. Polit. Stud. 1975, 8, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teune, H.; Przeworski, A. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger, S.; Gottschalk, P. Work, poverty, and the working poor: A multifaceted problem. Mon. Labour Rev. 1986, 109, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hantrais, L. International Comparative Research: Theory, Methods and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Airio, I. Change of Norm? In-Work Poverty in a Comparative Perspective; Kela: Helsinki, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D. The feminization of poverty: Women, work, and welfare. Urban Soc. Chang. Rev. 1978, 11, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, I.; Nolan, B. In-Work Poverty; GINI Discussion Paper No. 51; Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Casas, R.; Latta, M. Working Poor in the European Union; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, D.; Fullerton, A.S.; Cross, J.M. More than just nickels and dimes: A cross-national analysis of working poverty in affluent democracies. Soc. Probl. 2010, 57, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonoli, G. Time Matters: Postindustrialization, New Social Risks and Welfare State Adaptation in Advanced Industrial Democraties. Comp. Political Stud. 2007, 40, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Territory, Authority, Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Seccombe, K.; Amey, C. Playing by the rules and losing: Health insurance and the working poor. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 7, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Craypo, C. The working poor and the working of American labour markets. Camb. J. Econ. 2000, 24, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupured, M. Promoting Upward Mobility for the Working Poor. Rural South: Preparing for the Challenges of the 21st Century. 2000. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED444785 (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Davis, J.C.; Huston, J.H. Counting the working poor. South. Econ. J. 1991, 1, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, J.R. How to help the working poor develop assets. J. Soc. Soc. Welfare 1994, 21, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Tickamyer, A.R. The working poor in rural labor markets: The example of the southeastern United States. Rural Poverty Am. 1992, 4, 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D.; Kissam, E. Working Poor: Farmworkers in the United States; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Puente, S. Race, Ethnicity, and Working Poverty: A Statistical Analysis for Metropolitan Chicago; ERIC: Martinique, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office ILO. Women swell ranks of working poor. World Work Mag. ILO 1996, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff, A. The face of globalization: Women working poor in Canada. Can. Woman Stud. 2000, 20, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Working Poor in Europe. 2010. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_files/pubdocs/2010/25/en/2/EF1025EN.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2016).

- Sartori, G. Comparative Constitutional Engineering: An Inquiry into Structures, Incentives, and Outcomes; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Labour Force Participation Rate, Female (% of Female Population Ages + 15) (Modelled ILO Estimated), China, 2016; The World Bank Databank: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Dong, X.Y. Gender and Occupational Mobility in Urban China during the Economic Transition; University of Winnipeg: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Long, W. Gender earnings disparity and discrimination in urban china: Unconditional quantile regression. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2013, 5, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Li, B. Trends in China’s gender employment and pay gap: Estimating gender pay gaps with employment selection. J. Comp. Econ. 2014, 42, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum 2016. The Global Gender Gap Report 2016. Available online: http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2016/ (accessed on 24 April 2015).

- Weber, M. From Max Weber: Essays in sociology. Edited, with an introduction by H.H. Gerth & C.Wright Mills; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Willms, J. Conversations with Ulrich Beck; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ponthieux, S. In-work poverty in the EU. Eurostat: methodologies and working papers. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).