Research for the People, by the People: The Political Practice of Cognitive Justice and Transformative Learning in Environmental Social Movements †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Including Justice in Transformative Environmental Learning

- Activist-researchers’ work in the Changing Practice course shows how engaging in cognitive justice throughout the course, and in the development of their change projects, was transformative and transgressive. The Vaal Environmental Justice Alliance case directly and explicitly challenges certain aspects of society that have become normalised.

- Activist-researchers learned to act and reflect on how their work can transform their practice based on issues that activist researchers raised. This contributed to both the theory and practice of their learning, and to the theory and practice of cognitive justice.

1.2. What Is Cognitive Justice?

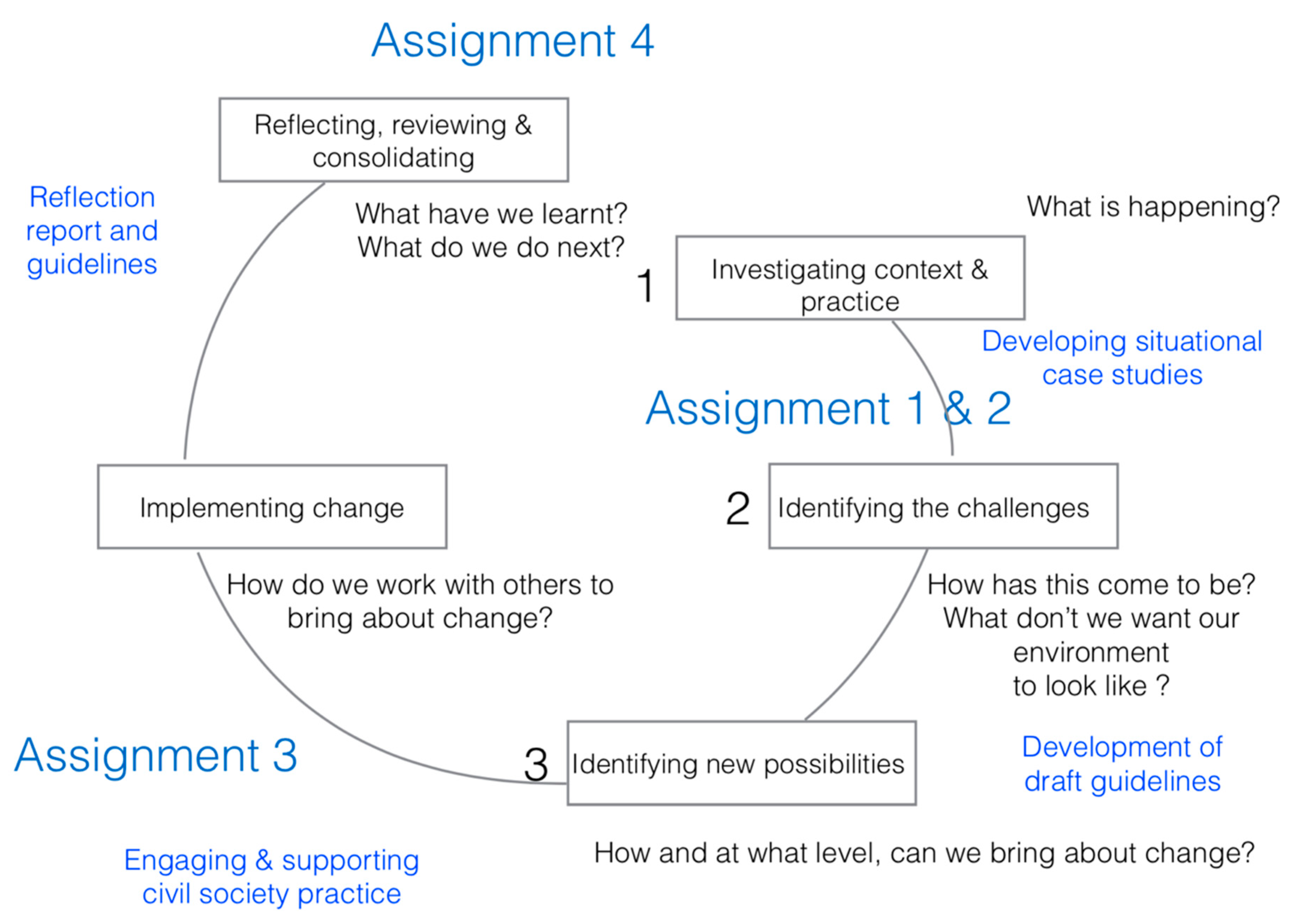

1.3. The Changing Practice Courses

2. Materials and Methods

Critical Realism and Transformative Social Action

- From ‘it is happening’ to ‘what is happening?’ (absent the absence of acknowledgement that there is a problem, rather than assume the status quo to be normal)

- From ‘what is happening? to ‘how can this be?’ (absent the absence of an explanation for the problem)

- From ‘how has this come to be?’ to ‘how can this be transformed?’ (absent the absence of action to address the problem)

- Material transactions with nature: this refers to transformations at the level of personal and collective interdependence with species, habitats, landscapes, the planet, and even the cosmos ([48] p. 6).

- Social interactions between people: seeing relationships as a core ingredient for action, and acknowledging that individuals and social systems cannot be reproduced or transformed without social interactions ([41] p. 6). Social interactions between people are described by Bhaskar as on a continuum between the two poles of enabling, which Bhaskar refers to as power one (power as transformative capacity—‘power with’) and oppressive, which he calls power two (power as oppressive as in a master-slave relationship—‘power over’) [40]. We have the choice to reproduce oppression or move towards transformation in enacting our relationships.

- Social structure: although social structure precedes agency, the form that social structures take is dependent on what we have done and what we will do.

- The embodied personality: an individual is an embodied historical, feeling and thinking being. There are many ways in which individual freedom can be suppressed—human bodies can be incarcerated or treated with disrespect, ways of thinking and knowing the world can be unequally valued, individuals do not have the same access to education. Transformative action attempts to free the body from health risks, free the mind through more open ways of thinking, and heal psychological conditions such as lack of confidence or sense of inferiority—all of these being constraints that can inhibit action [40].

3. Results

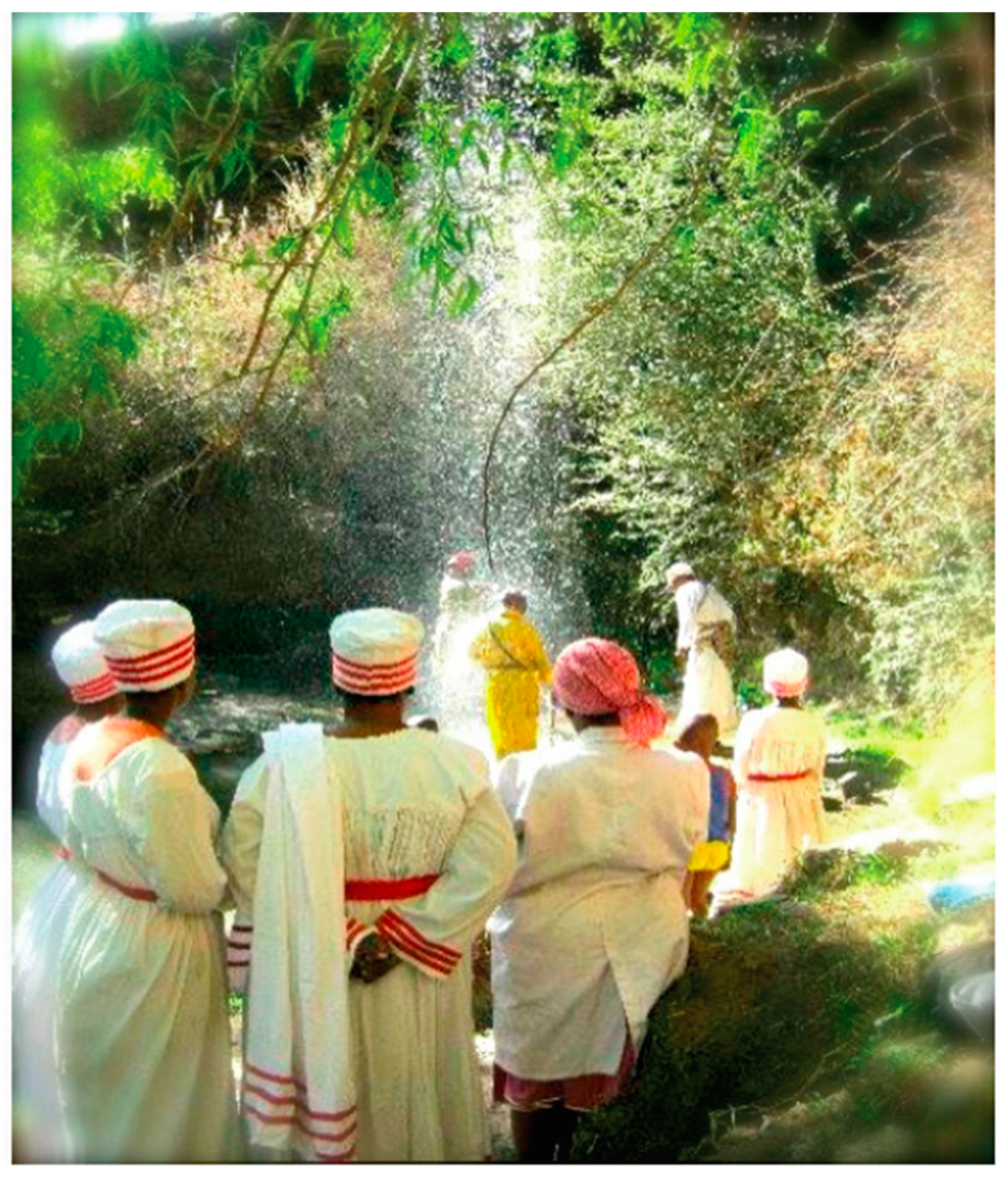

3.1. ‘Water and Tradition’: A Case Study of the VEJA Change Project

“We began to understand the moral value of cultural religious groups’ practice based on natural water” ([4] p. 1).

3.2. The VEJA Change Project and How Cognitive Justice Led to Transformative Action

From it is happening’ to ‘what is happening?’

From ‘what is happening? to ‘how can this be?’ (absent the absence of an explanation for the problem).

From ‘how has this come to be?’ to ‘how can this be transformed?’ (absent the absence of action to address the problem).

3.2.1. How Spiritual Practices Are Affected by the Polluted Rivers

What Is Happening?

How Can This Be?

How to Transform?

3.2.2. Relationships have been Broken Down by Past and Current Inequities

What Is Happening?

How Can This Be?

How to Transform?

3.2.3. Women Do Not Have the Same Freedoms as Men

What Is Happening?

How Can This Be?

How to Transform?

4. Possibilities for Transformative Social Action Catalysed by the VEJA Change Project

4.1. Catalysed Agency at the Four Dimensions of Being

4.1.1. What Did We Absent at the Level of Material Interaction with the World through the Changing Practice Course and the VEJA Change Project?

4.1.2. What Did We Absent at the Level of Being in Relation to One Another through the Changing Practice Course and the VEJA Change Project?

4.1.3. What Did We Absent at the Level of Structure through the Changing Practice Course and the VEJA Change Project?

- (a)

- As facilitators we became more sensitive to different knowledge systems, both through the way we interacted with participants and in the way we reflected on our own practice. Participants were emboldened by the way their own knowledge was given centre stage, and this developed trust and confidence between us. It did not remove historical inequalities, but it did allow us to find a different way of being and working together.

- (b)

- Thandiwe’s brave confrontation with the experience of sexual harassment made us realise that, as activist-researchers and educator-activists, we needed to address head-on the relations between men and women. This led to serious discussions on gender with the South African Water Caucus, which resulted in gender equality being added to the SAWC principles and a working document being produced on gender and water. It also led to our decision to introduce gender dialogues into all follow-up Changing Practice courses.

4.1.4. What Is Catalysed by Changes at the Level of the Embodied Personality?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, J.; Victor, M.; Burt, J.; Pereira, T.; Ngcozela, T.; Ndhlovu, D.; Ngcanga, T.; Tshabalala, M.; James, M. Citizen Monitoring of the NWRS2; Water Research Commission: Tshwane, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, J.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Rivers, N.; Berold, R.; Ntshudu, M.; Wigley, T.; Stanford, R.; Jenkin, T.; Buzani, M.; Kruger, E. The Role of Knowledge in a Democratic Society: Investigations into Mediation and Change-Oriented Learning in Water Management Practices; Water Research Commission: Tshwane, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S.; Mojab, S. Revolutionary Learning: Marxism, Feminism and Knowledge; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tshabalala, M.; Thandiwe, N.; Samson, M. Water and Tradition; Environmental Monitoring Group: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Friends of the Earth Europe. Overconsumption? Our Use of the World’s Natural Resources. 2009. Available online: https://cdn.friendsoftheearth.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/overconsumption.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Orr, D.W. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B.; Wals, A.E.J. Debating education for sustainable development 20 years after Rio: A conversation between Bob Jickling and Arjen Wals. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Warmington, P.; Daniels, H.; Edwards, A.; Brown, S.; Leadbetter, J.; Martin, D.; Middleton, D.; Parsons, S.; Popova, A. Surfacing contradictions: Intervention workshops as change mechanisms in professional learning. In Proceedings of the British Education Research Association Annual Conference, Pontypridd, UK, 14–17 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Engestrom, Y. Enriching the theory of expansive learning: Lessons from journeys toward coconfiguration. Mind Cult. Act. 2007, 14, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.L.; Clover, D.E.; Crowther, J.; Scandrett, E. Learning and Education for a Better World: The Role of Social Movements; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Choudry, A. Learning Activism: The Intellectual Life of Contemporary Social Movements; University of Toronto Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Choudry, A. (Almost) everything you always wanted to know about activist research but were afraid to ask: What activist researchers say about theory and methodology. Contention 2014, 1, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Boughton, B. Popular Education and the ‘party line’. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2013, 11, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hursh, D.; Henderson, J.; Greenwood, D. Environmental education in a neoliberal climate. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudry, A. Transnational activist coalition politics and the de/colonisation of pedagogies of mobilisation: Learning from anti -neoliberal indigenous movement articulations. Int. Educ. 2007, 37, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Darder, A. Neoliberalism in the academic borderlands: an on-going struggle for equality and human rights. Educ. Stud. 2012, 48, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H.; Samalavicius, A. Higher education and neoliberal temptation. Kult. Barai 2016, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, A. From metabolic rift to “metabolic value”: Reflections on environmental sociology and the alternative globalization movement. Organ. Environ. 2010, 23, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, A. Ecofeminism as Politics: Nature, Marx and the Postmodern, 2nd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Ali, M.B.; Mphepo, G.; Chaves, M.; Macintyre, T.; Pesanayi, T.; Wals, A.; Mukute, M.; Kronlid, D.; Tran, D.T.; et al. Co-designing research on transgressive learning in times of climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 20, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, J.; Pereira, T.; Lotz-Sisitka, H. Entering the Mud: Transformative Learning and Cognitive Justice as Care Work. Unpublished Article, Latest Draft 3 December 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330115056_Entering_the_mud_Transformative_learning_and_cognitive_justice_as_care_work (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- Burt, J.; James, A.; Walters, S.; von Kotze, A. Working for living: Popular education as/at work for social-ecological justice. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. in press.

- Visvanathan, S. Knowledge, justice and democracy. In Science and Citizens: Globalization and the Challenge of Engagement; Leach, M., Scoones, B., Wynne, B., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2005; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Tiberghien, J. Towards a ‘global educational justice’ research paradigm: Cognitive justice, decolonizing methodologies and critical pedagogy. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2004, 2, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.D.S. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against the Epistemicide; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.D.S. Beyond abyssal thinking. Binghamt. Univ. Rev. 2007, 30, 45–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kincholoe, J. Knowledge and Critical Pedagogy: An Introduction; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamnjoh, F.B. Potted plants in greenhouses’: A critical reflection on the resilience of colonial education in Africa. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2012, 47, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, S.J. Voice of the researcher: Extending the limits of what counts as research. J. Res. Pract. 2007, 3, M3. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, S. Learning from the Other; State University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.J. Whose Knowledge Counts? Exploring Cognitive Justice in Community-University Collaborations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, K. Towards an epistemological monoculture: Mechanisms of epistemicide in European research publication. Engl. Sci. Res. Lang. Debates Discourses 2015, 2, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, K. The transparency trope: Deconstructing english academic discourse. Discourse Interact. 2015, 8, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, J.; Pereira, T.; Lusithi, T.; Horgan, S.; Ndlhovu, D.; Wilson, J.; Munnik, V.; Boledi, S.; Jolobe, C.; Kakaza, L.; et al. Changing Practice: Olifants Catchment Final Report; Environmental Monitoring Group: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Munnik, V.; Burt, J.; du Toit, D.; Price, L. Report on the Forum of Forums; Water Research Commission: Tshwane, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Price, L. Some implications of MetaReality for environmental educators. In Critical Realism, Environmental Learning and Socio-Ecological Change; Price, L., Lotz-Sisitka, H., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2016; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, J.; James, A.; Price, L. A peaceful revenge: achieving structural and agential transformation in a South African context using cognitive justice and emancipatory social learning. J. Crit. Realism 2018, 17, 492–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism; Hartwig, M., Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. Dialectic: The Pulse of Freedom; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. Scientific Realism and Human Emancipation; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R.; Scott, D. A Theory of Education; Springer: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Price, L. Caring, healing and befriending: An interdisciplinary critical realist approach to reducing oppression and violence against women in Southern Africa. In Critical Realist Reading Group, Institute of Education; University College London: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. A Realist Theory of Science; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. The Possibility of Naturalism; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, M. Dictionary of Critical Realism; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olvitt, L.L. Education in the anthropocene: Ethico-moral dimensions and critical realist openings. J. Moral Educ. 2017, 46, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowes, D.; Munnik, V. The Destruction of the Highveld Part 1: Digging Coal; GroundWork: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlhovu, D.; Mashile, A.; Mdluli, P. Saving Moholoholo; Environmental Monitoring Group: Cape Town, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and Ethics of Knowing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Santos, B. The World Social Forum and the global left. Politics Soc. 2008, 36, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan, S. Alternative science. Theory Cult. Soc. 2006, 23, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P. “Living water” in Nguni healing traditions, South Africa. Worldviews 2013, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burt, J. Research for the People, by the People: The Political Practice of Cognitive Justice and Transformative Learning in Environmental Social Movements. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205611

Burt J. Research for the People, by the People: The Political Practice of Cognitive Justice and Transformative Learning in Environmental Social Movements. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205611

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurt, Jane. 2019. "Research for the People, by the People: The Political Practice of Cognitive Justice and Transformative Learning in Environmental Social Movements" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205611

APA StyleBurt, J. (2019). Research for the People, by the People: The Political Practice of Cognitive Justice and Transformative Learning in Environmental Social Movements. Sustainability, 11(20), 5611. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205611