Coffee Roasters’ Sustainable Sourcing Decisions and Use of the Direct Trade Label

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- as a “general concept,” whereby coffee is sourced directly from farmers;

- as a “voluntary scheme,” which is “a claim that a particular set of standards is followed;” and

- as a marketing strategy or label.

2. Literature Review

- “Exceptional coffee quality is a must.

- The grower must be committed to sustainable environmental and social practices.

- The price paid to the grower or local co-op must be at least 25% above the Fair Trade price.

- All trade participants must allow transparent financial disclosures back to the individual farmers.

- Intelligentsia team members must visit the farm or co-op a minimum of once per harvest season. More often, visits will take place three times per year: pre-harvest, mid-harvest, and post-harvest [21].”

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Design

3.2. Interview Approach

3.3. Coding Process

3.4. Description of Interviewed Roasters

4. Results

4.1. Motivations to Source Coffee Directly from Farmers

4.1.1. Business Motivations

“…We think of coffee as a pyramid…Relatively little of the best coffee, and there is a lot of the worst coffee. The better the coffee is, the less there is available. That scarcity is what drives the value. I personally believe in segmentation and that is the heart of the (company) sourcing model. Segmentation with an eye to quality-based differentiation and access to specialty markets.”

4.1.2. Social Responsibility Motivations

4.2. Motivations to Communicate Sourcing Practices to Customers (Inclusive of Using the DT Label)

4.3. Motivation Not to Use the DT Label, Despite Using DS Practices

4.3.1. The DT Label is Unclear

“It became very murky.(In the) public sphere and usage of that phrase. That terminology became very clouded. And so this kind of coincided with us focusing more and more on transparency within our supply chain.” (Roaster 1).

4.3.2. The DT Label is Unnecessary

“It is not that we sit around and discuss whether this year we need to start using Direct Trade. Now that the vast majority of our coffees are sourced collaboratively. But we are not having those conversations. Conversations are more (about) ‘how to do we get people to appreciate specific coffees?”

“I think they think that Direct Trade—it means that I went down there and said ‘we are deciding on $4 a pound, and you get all that $4 a pound.’ They also think that farmer X is picking all the coffee and busting his ass day in and day out and they also assume that they are really poor… And it is completely devoid of any influence from the C market. If they have heard of the C market. Maybe nobody calls it the C market. But devoid of this mythic evil establishment thing.”

4.3.3. Free Riders Harm the DT Label

“Yeah, we are still 100% committed to principles of what we are doing. It is less about the brand name Direct Trade. I don’t care about that. It is about the process of buying coffee. We have actually considered changing and rebranding away from Direct Trade. The Direct Trade words have been co-opted and cheapened.”

“Where I have a problem is with the ease of saying “I do Direct Trade because I went on an origin trip and I met a producer and I’m buying his coffee every year.” Oh wow, it’s that simple. Piggybacking on the efforts of companies that put some meat behind it. I do have some moderate issue with that… These companies are doing all these things to show that what they are calling Direct Trade is really a thing and you’re just riding that train without putting in the work and the resources. But because you can do that and no one is stopping you, no one is suing you, “cool, good for you.”

4.4. Other Stakeholder Perspectives on DT and DS

4.4.1. Benefits for Sourcing Directly

4.4.2. Communicate Sourcing Practices to Customers

“Direct Trade is being used a lot. I think it is being used and interpreted by consumers as “Oh good, you are treating the farmer well and they are getting a good price.” So they are making a lot of assumptions that you could make safely in the past with Fair Trade documentation.”

4.4.3. Challenges with DT label

5. Discussion

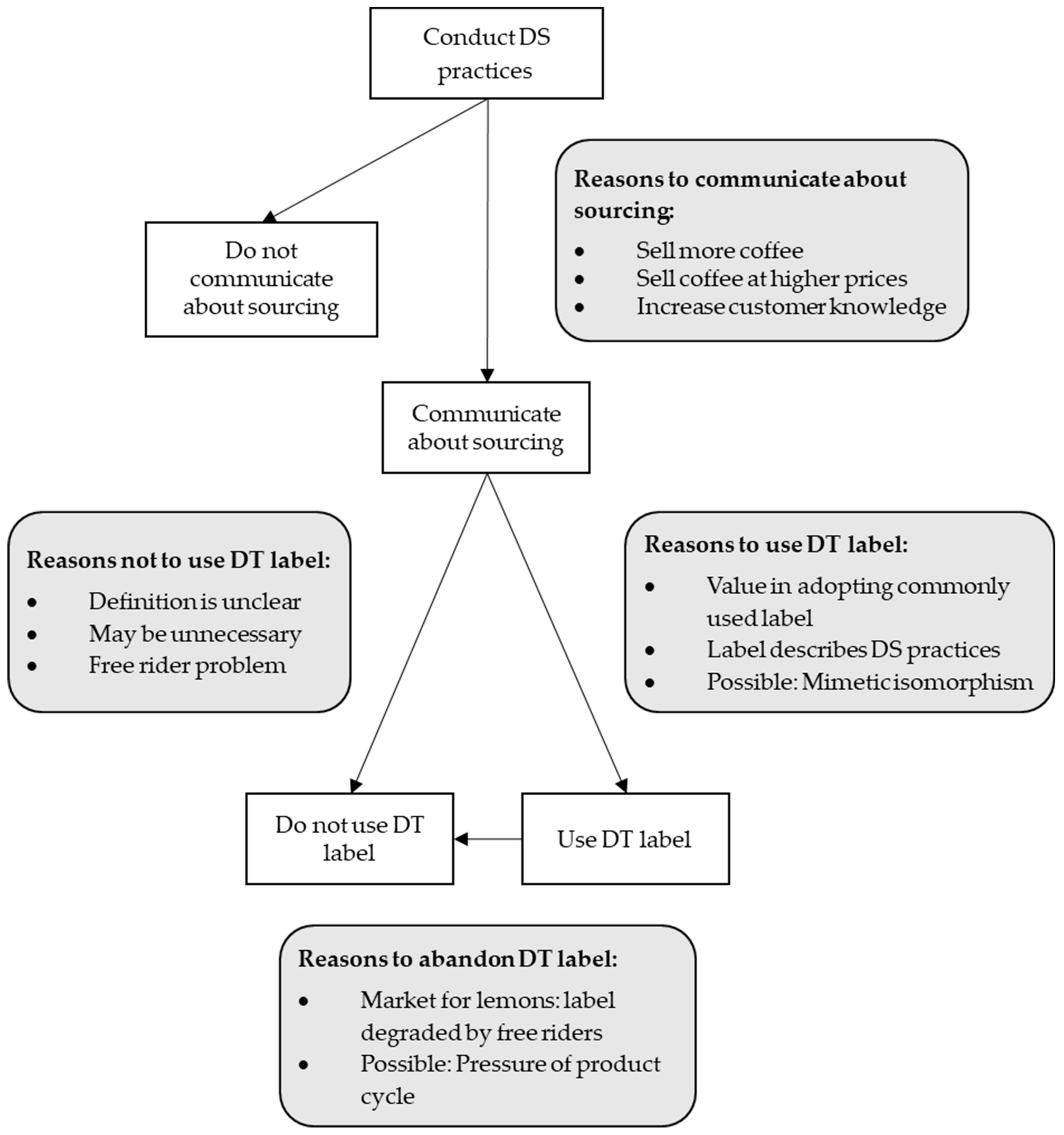

5.1. DS Roasters’ Decision-Making Model

5.2. Possible Solutions: Third-Party Certification and Shared Self-Certification Standards

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietz, T.; Auffenberg, J.; Estrella Chong, A.; Grabs, J.; Kilian, B. The Voluntary Coffee Standard Index (VOCSI). Developing a Composite Index to Assess and Compare the Strength of Mainstream Voluntary Sustainability Standards in the Global Coffee Industry. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, D.; Ponte, S. Standards as a New Form of Social Contract? Sustainability Initiatives in the Coffee Industry. Food Policy 2005, 30, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, J.; Manning, S.; von Hagen, O. The Emergence of a Standards Market: Multiplicity of Sustainability Standards in the Global Coffee Industry. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 791–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raynolds, L.T. Mainstreaming Fair Trade Coffee: From Partnership to Traceability. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.A. What Are We Getting from Voluntary Sustainability Standards for Coffee? Center for Global Development, Policy Paper 129: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, F.; Ramasar, V.; Nicholas, K.A. Problems with Firm-Led Voluntary Sustainability Schemes: The Case of Direct Trade Coffee. Sustainability 2017, 9, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M. God in a Cup: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Coffee; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, E.; Kjeldsen, C.; Kerndrup, S. Coordinating Quality Practices in Direct Trade Coffee. J. Cult. Econ. 2016, 9, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, S. Direct Trade: Going Straight to the Source. Available online: http://www.scanews.coffee/2012/02/14/direct-trade-the-questions-answers/ (accessed on 11 February 2017).

- Hernandez-Aguilera, J.N.; Gómez, M.I.; Rodewald, A.D.; Rueda, X.; Anunu, C.; Bennett, R.; van Es, H.M. Quality as a Driver of Sustainable Agricultural Value Chains: The Case of the Relationship Coffee Model. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C. Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Can Fair Trade, Organic, and Specialty Coffees Reduce Small-Scale Farmer Vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua? World Dev. 2005, 33, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daviron, B.; Ponte, S. The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Lotade, J. Do Fair Trade and Eco-Labels in Coffee Wake up the Consumer Conscience? Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, M.; Busch, L. Third-Party Certification in the Global Agrifood System: An Objective or Socially Mediated Governance Mechanism? Sociol. Ruralis 2008, 48, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M. Is Direct Trade Fair? Available online: http://sprudge.com/is-direct-trade-fair-110410.html (accessed on 11 February 2017).

- Raynolds, L.T.; Murray, D.; Heller, A. Regulating Sustainability in the Coffee Sector: A Comparative Analysis of Third-Party Environmental and Social Certification Initiatives. Agric. Human Values 2007, 24, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Pelupessy, W. Governing the Coffee Chain: The Role of Voluntary Regulatory Systems. World Dev. 2005, 33, 2029–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, K.B.; Kerr, J. Limitations of Certification and Supply Chain Standards for Environmental Protection in Commodity Crop Production. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C.; Schaefer, F.; Skalidou, D. The Effectiveness of Agricultural Certification in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. World Dev. 2018, 112, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.; Boons, F.; von Hagen, O.; Reinecke, J. National Contexts Matter: The Co-Evolution of Sustainability Standards in Global Value Chains. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intelligentsia. Direct Trade. Available online: https://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/learn-do/community/intelligentsia-direct-trade (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Holland, S. Lending Credence: Motivation, Trust, and Organic Certification. Agric. Food Econ. 2016, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.C.; Salois, M.J. Local versus Organic: A Turn in Consumer Preferences and Willingness-to-Pay. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, C. The Problem With Fair Trade Coffee. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2011, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- CRS Coffeelands. Third-Rail Communications. Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2015/11/third-rail-communications/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Fairtrade America. Coffee. Available online: http://fairtradeamerica.org/Fairtrade-Products/Coffee (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Fairtrade International. Small-scale producer organizations. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net/standard/spo (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Fairtrade International. Fairtrade Standard for Coffee for Small Producer Organizations and Traders; Fairtrade International: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, B.; Sheldon, I. Credence Good Labeling: The Efficiency and Distributional Implications of Several Policy Approaches. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 89, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.F. Certification of Socially Responsible Behavior: Eco-Labels and Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2009, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M. The Path to Distinction: Nurturing Separation in Nariño. Roast Mag. 2016, 4, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M. Show Me the Money: Direct Trade Volume 3. Available online: https://sprudge.com/show-me-the-money-direct-trade-volume-3-123856.html (accessed on 7 September 2019) .

- Weissman, M. Direct Trade in the Shadows. Available online: https://sprudge.com/direct-trade-in-the-shadows-116639.html (accessed on 7 September 2019) .

- CRS Coffeelands. What is the standard for (disclosure in) Direct Trade? Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2011/06/what-is-the-standard-for-disclosure-in-direct-trade/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- CRS Coffeelands. More on Direct Trade standards. Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2011/07/more-on-direct-trade-standards/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- CRS Coffeelands. Research Review: Counter Culture’s Case Study on the Social Impact of Microlots. Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2012/04/research-review-counter-cultures-case-study-on-the-social-impact-of-microlots/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Ragasa, C.; Lambrecht, I.; Kufoalor, D.S. Limitations of Contract Farming as a Pro-Poor Strategy: The Case of Maize Outgrower Schemes in Upper West Ghana. World Dev. 2018, 102, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, G.; Vellema, W.; Desiere, S.; Weituschat, S.; Haese, M.D. Contract Farming for Improving Smallholder Incomes: What Can We Learn from Effectiveness Studies? World Dev. 2018, 104, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolwig, S.; Gibbon, P.; Jones, S. The Economics of Smallholder Organic Contract Farming in Tropical Africa. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, M.; Colen, L.; Swinnen, J.F.M. Globalisation and Poverty in Senegal: A Worst Case Scenario? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F. Contract Farming: Opportunity Cost and Trade-Offs. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minten, B.; Randrianarison, L.; Swinnen, J.F.M. Global Retail Chains and Poor Farmers: Evidence from Madagascar. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oya, C. Contract Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey of Approaches, Debates and Issues. J. Agrar. Chang. 2012, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whole Foods Market. Whole Trade. Available online: https://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/mission-values/whole-trade-program (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Land of a Thousand Hills Coffee. Collaborative Trade Postcards 100/pack. Available online: https://shop.landofathousandhills.com/products/collaborative-trade-locations-postcard (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Simpatico Coffee. Farmer Direct Coffee. Available online: https://simpaticocoffee.com/pages/straight-trade-coffee (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 8th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. How 7 people test 400 million pounds of Starbucks coffee a year. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/3025212/how-7-people-test-400-million-pounds-of-starbucks-coffee-a-year (accessed on 6 September 2019) .

- Ponte, S. Brewing a Bitter Cup? Deregulation, Quality and the Re-Organization of Coffee Marketing in East Africa. J. Agrar. Chang. 2002, 2, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Codron, J.-M.; Busch, L.; Bingen, J.; Harris, C. Global Change in Agrifoods Grades and Standards: Agribusiness Strategic Responses in Developing Countries. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2001, 2, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Delanchy, M.; Remaud, H.; Zepeda, L.; Gurviez, P. Consumers’ Perceptions of Individual and Combined Sustainable Food Labels: A UK Pilot Investigation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, C.R.; Johnston, R.J.; Donath, H. Assessing Consumer Preferences for Ecolabeled Seafood: The Influence of Species, Certifier, and Household Attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 81, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Building Social Capital into the Disrupted Green Coffee Supply Chain: Illy’s Journey to Quality and Sustainability. In Organizing Supply Chain Processes for Sustainable Innovation in the Agri-Food Industry; Cagliano, R., Caniato, F.F.A., Worley, C.G., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, F.E.; Bansal, P.; Slawinski, N. Scale Matters: The Scale of Environmental Issues in Corporate Collective Actions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1411–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Lenox, M.J. Industry Self-Regulation without Sanctions: The Chemical Industry’s Responsible Care Program. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 698–716. [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A.; Janssen, M.; Ostrom, E. Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bajde, D.; Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G.; Winchester, M.; Arding, R.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trader Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2013, 13, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufer, D.; Lin, W.; Ortega, D.L. Personality Traits and Preferences for Specialty Coffee: Results from a Coffee Shop Field Experiment. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Voluntary Standard | Overview | Structure | Means for Roaster to Purchase Coffee | Verification System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Trade | Farmers negotiate price and quality with roasters, without intermediaries. | In general, roasters and farmers must have a direct relationship and directly negotiate quality and price. Roasters must visit farmers in person. | Contract with farmer, hire export/import companies to transport coffee to roaster. | None |

| Fairtrade International | Farmer cooperative members receive a minimum price and price premium [26]. | Must be a small scale, democratically organized producer organization [27]. Fairtrade price is based on the commodities market price plus a Fairtrade differential plus a price premium [28]. | Purchase coffee from importer who purchased coffee from Fair Trade-certified cooperative. | Third-party auditor |

| Interviewee Number | Size (Pounds Roasted Per Year) | Level of Direct Sourcing (DS) | Direct Trade (DT) Labeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roaster 1 | Medium/Large (600,000+) | Intensive | Used previously but stopped |

| Roaster 2 | Medium/Large (600,000+) | Intensive | Consistently uses |

| Roaster 3 | Medium (300,000–599,999) | Intensive | Consistently uses |

| Roaster 4 | Medium (300,000–599,999) | Intensive | Inconsistently uses |

| Roaster 5 | Medium (300,000–599,999) | Some | Inconsistently uses |

| Roaster 6 | Medium/Large (600,000+) | Some | Has never used |

| Roaster 7 | Small (1–299,999) | No | Consistently uses |

| Roaster 8 | Medium (300,000–599,999) | Intensive | Has never used |

| Roaster 9 | Medium/Large (600,000+) | Intensive | Has never used |

| Roaster 10 | Small (1–299,999) | Some | Consistently uses |

| Roaster 11 | Medium/Large (600,000+) | Some | Has never used |

| Stakeholder 1 | Non-profit | ||

| Stakeholder 2 | Non-profit | ||

| Stakeholder 3 | Importer | ||

| Motivation | Description | Illustrative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| A. Business | DS benefits the roaster | “We get consistent supply of quality. We are serving coffees we have bought for 8 years now. Every year they come back on menu increases their popularity. People really enjoy season by season, or harvest by harvest coming back and drinking the (specific coffee). Those coffees will always sell better than new relationships—almost always. And how we build our whole buying program, we would never get the level of quality in a buying program without doing it this way.” (Roaster 8) |

| A.1. Better quality coffee | DS provides better quality coffee than other sourcing mechanisms | “It soon became pretty obvious on both sides of the equation that there was so much coffee out there that was just getting consolidated. The transparency was getting lost. The coops, they were blending the best—some really amazing coffee—into their overall blends. To just hit a standard market differential. So a lot of the quality was just being consolidated or lost…And so the roasters were able to discover this and point this out and then offer differentiated prices and all of that. What producers got in exchange was all this marketing as a result and origins themselves got marketing. And it was so good for the marketplace and the eventual benefit of everyone doing this is that customers know what to ask for and we hope that eventually know what to look for.” (Roaster 9) |

| A.2. Cultivate long-term sourcing relationship | DS builds long-term relationships with farmers, wherein roasters can predict quality, volume, price, and other elements | “Coffee quality—it ideally means that if I found some really amazing coffee from a single, small producer hopefully if we manage that relationship well we can keep sourcing good quality coffee in years to come.” (Roaster 4) |

| B. Social Responsibility | Roasters believe DS benefits the farmer | “There’s just not a lot of independent companies left… You’ve got (venture capital) money and investors. Companies like Nestle who are buying water from communities and then selling it back to them. They are buying coffee companies. They aren’t going to take this route. That’s capitalism... (Roaster 8′s approach) is like the anti-capitalism. Or it’s at least on the opposite spectrum extreme of capitalism. Capitalism is all about making money. For the people who are at the bottom of the chain thousands of miles away, of any chain they are the folks who get the shit end of the stick. That’s where the profit is built.” (Roaster 8) |

| B.1. Increased farmer income | Roasters believe DS may increase farmer income | “On the payment side, to make a lot of the stuff happen farmers have to get paid a decent amount where they are not just getting their basic living needs met, but they have more money to invest back into their farm. It is important for us to pay living wages relative to the economies down there so they can reinvest back into their farms so that quality can be maintained or increase.” (Roaster 4) |

| B.2. Increased trust between farmers and roasters | Heightened trust sustains relationship through good and bad years | “I’ve seen a lot of these market linkages occur for producers and it is really pretty magical because of what it does. I’ve seen that kind of relief. It’s like finding a good investor if you are a business. This person gets what I’m doing, they want to support me. …They understand where I’m going and I have their support.’ (It is) not without its tension, but I think that is a huge deal.” (Roaster 9) |

| B.3. Increased farmer learning | Farmers learn new approaches to growing and processing coffee | “(The) kind of things we are talking about include risk. Like ‘try this new harvest process, or we want you to try this new variety that is higher yielding and less susceptible to rust.’ But man, it’s going to produce a beautiful coffee. When we do this, we sometimes facilitate access to the tree itself. We absorb some of that risk. (There is) agreement that we will purchase coffee from an experiment whether it works on the coffee Table or not and we will validate, then we will move forward.” (Roaster 2) |

| Motivation | Description | Illustrative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| A. Increased sales and/or prices | Roasters believe that customers would buy and/or pay more for coffee if they knew more about sourcing | “We have developed these fabulously complex and rich sourcing models and it is sometimes frustrating that just at a time when there is so much discourse in food... and our chefs are rock stars and sourcing and seasonality and local is all ascendant in food culture. That’s what we’ve been about in Direct Trade for 15 years. Sometimes we wish it would resonate more. Wish people would see that everything they are celebrating in some ways we feel like—‘hey we have been talking about this for a long time.’ In that sense—would people buy more if they knew more about it? If you look at the way people respond to restaurants …Yeah, this is also going into their coffee. I would think they would be more excited about it.” (Roaster 2) |

| B. Increased customer understanding | Roasters think that most customers do not understand how coffee is sourced; sharing information with them would help solve this problem, which in turn could drive sales | “I think that a lot of times, even educated coffee drinkers might make a bit of a mistake and not really understanding the structure in which the coffee is grown and sold. A lot of people just assume that it is one person on a small family farm—maybe the structure you would see on small family farms in the US. But…the way a farm looks might be totally different depending on (whether it is) a coop in Rwanda or a two hectare farm in Honduras.” (Roaster 4) |

| C. Intrinsic value in sharing with customers | Roasters care about sharing information for individual values-based reasons | “We appreciate those things. appreciate working with coops like Dakunde Kawa, (a) majority female run coop. So we like those stories. It is hard for me to really see how people respond to it. That’s more just a personal choice to make selections like that. It is hard to say what the impact is on sales.” (Roaster 11) |

| Reason | Description | Illustrative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| A. DT label is unclear | The label’s definition is not clear; standards differ across roasters | “I think each roaster just makes up their own set of qualifications. Is it you toured the farm with an importer and took some photos and you shook the farmer’s hand and you signed the contract for the coffee? Some people might call that direct. I don’t necessarily think that is especially direct.” (Roaster 5) |

| B. DT label is unnecessary | The label is not necessary to the roaster because customers do not understand and/or care or because the roaster has other ways of communicating | “We have been around for 25 years—we have had producers...relationships with producers for a number of years. I don’t feel like as a company we have ever had to jump on a bandwagon to distinguish ourselves. People ask questions and they want to know we have the relationships to show them. But it is not like we feel like we have to use a term that doesn’t have a descriptive position.” (Roaster 6) |

| C. Free riders devalue DT label | Roasters who do not source directly still use the DT label, reducing its value | “I just think that a lot of people buy coffee third party that is…they aren’t actually purchasing it directly. There is someone handling all of it and they call that Direct Trade… I think in certain cases it is definitely not. Sometimes I can just tell based on…let me give you an example. If you are buying from a broker, you are buying a coffee that I know came from a certain place and they rename it something else to conceal its identity and then they sell that as Direct Trade. They definitely don’t know how much the farmer got paid because the broker doesn’t want to tell them that. I see that a lot.” (Roaster 8) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerard, A.; Lopez, M.C.; McCright, A.M. Coffee Roasters’ Sustainable Sourcing Decisions and Use of the Direct Trade Label. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195437

Gerard A, Lopez MC, McCright AM. Coffee Roasters’ Sustainable Sourcing Decisions and Use of the Direct Trade Label. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195437

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerard, Andrew, Maria Claudia Lopez, and Aaron M. McCright. 2019. "Coffee Roasters’ Sustainable Sourcing Decisions and Use of the Direct Trade Label" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195437

APA StyleGerard, A., Lopez, M. C., & McCright, A. M. (2019). Coffee Roasters’ Sustainable Sourcing Decisions and Use of the Direct Trade Label. Sustainability, 11(19), 5437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195437