Abstract

This paper analyzes motivations for coffee roasters to source directly from farmers and how roasters decide whether to use the Direct Trade sustainability label. Direct Trade is an uncertified label connoting an approach wherein roasters negotiate coffee price and quality with farmers without intermediaries, with purported farmer income benefits. We examine semi-structured interviews with 11 US roasters and three coffee stakeholders to identify motivations to source directly, provide customers sourcing information, and use or reject the Direct Trade label. We find that roasters directly source coffee primarily for quality reasons and communicate about sourcing because they believe customers would value coffee more if they understood their sustainable sourcing practices. However, the lack of a clear definition for the Direct Trade label, coffee roaster concerns about the label’s utility, and the threat of “free riders” disincentivizes label use. Without a shared label, customers face high costs for information about directly sourced coffee, which may limit the expansion of a sourcing practice that could benefit farmers.

1. Introduction

While coffee is largely consumed in Northern countries, it is produced in equatorial countries, often by low-income farmers. Numerous approaches to coffee sourcing standards aim to make the coffee industry more socio-economically and environmentally sustainable [1,2,3,4,5]. These include well-known, third-party certified labels such as Fair Trade, Organic, and UTZ, which aim to improve farmer incomes, produce coffee without the extensive use of chemicals, and source coffee in a holistically sustainable manner, respectively [1]. They also include non-certified labels such as Direct Trade.

Direct Trade (DT) is a socio-economic sustainability label developed in the early 2000s by US-based specialty coffee “roasters” (companies that purchase, roast, and sell coffee) which describes coffee that is sourced and purchased through direct negotiation with farmers [6,7]. Roasters such as Counter Culture Coffee, Intelligentsia Coffee, and Stumptown Coffee Roasters developed the DT label to describe coffee sourcing activities that involve not only direct negotiation with farmers, but also price premiums and regular travel to coffee farms to collaborate with farmers on improving coffee quality [7,8]. DT proponents see it as a means to obtain superb coffee—often small, unique “micro-lots”—in a way that benefits farmers [9]. Sourcing coffee directly from farmers is supposed to align incentives between buyers and farmers, rewarding farmers for producing high-quality coffee without intermediary traders taking part of the profits [9]. It also has the potential for giving farmers an avenue into the specialty coffee market, which is more stable than the commodity coffee market and provides farmers with better prices [10,11].

The DT label is a supply-driven label, because—rather than consumers demanding directly sourced coffee or civil society organizations working to create standards—it was developed by firms to describe practices they wanted to market to consumers [6,12,13]. MacGregor et al. (2017, p. 2) note three ways that “direct trade” can be used:

- as a “general concept,” whereby coffee is sourced directly from farmers;

- as a “voluntary scheme,” which is “a claim that a particular set of standards is followed;” and

- as a marketing strategy or label.

In our paper, we use the broader term of “direct sourcing” (DS) to describe sourcing coffee directly from farmers (MacGregor et al.’s “general concept” use), whether or not the roaster uses the DT label. We discuss DT as a voluntary scheme when referring to the standards that early adopters developed, but we generally use DT to refer to the marketing or labeling approach.

Because no binding certification system exists for DT, roasters can use the label without verification of the sourcing practices they use. Indeed, roasters differ considerably in their definitions of DT, which distinguishes DT from third-party certified labeling systems [8]. Hatanaka and Busch (2008, p. 73) describe third-party certification systems as those “in which third parties assess, evaluate and certify safety and quality claims against a particular set of standards and compliance procedures [14].” In the years following the label’s development, greater numbers of roasters began using the DT label [6]. This was followed by sectoral skepticism about the label and a contraction in usage by some early adopters [6,15]. This leads to questions about the utility of DT labeling to roasters, the utility of DS activities to roasters and farmers, and how the differences between label use and actual practices might influence sourcing approaches used by roasters and information delivered to consumers [6,15].

This study investigates three research questions aimed at understanding roasters’ motivations to source coffee directly from farmers and to use or not use the DT label. First, what motivates coffee roasters to source coffee directly from farmers? Second, what motivates coffee roasters to communicate sourcing practices to customers (inclusive of using the DT label)? Third, what motivates coffee roasters not to use the DT label, despite using DS practices? Beyond answering these questions, this paper considers possible paths forward for DT.

In considering these research questions, we qualitatively analyze semi-structured interviews with 11 US coffee roasters and three other types of coffee stakeholder organizations. This analysis builds on recent work by MacGregor, et al. noted above. These authors analyze three US-based and three Scandinavian DT roasters, with a focus on regulation (or lack thereof) of DT sourcing standards. They include DT founding companies Counter Culture Coffee, Intelligentsia, and Stumptown in the US and Coffee Collective (Denmark), Johan and Nyström (Sweden), and Koppi (Sweden) in Scandinavia [6]. They find that some US roasters are moving away from use of the DT label because the lack of standards coordination and enforcement have resulted in “co-optation” of the DT label (which we discuss as “free riding”) [6]. Among US roasters, they distinguish between largely quality-based motivations to source directly and mostly sustainability-based motivations to use DT as a marketing strategy. By comparison, MacGregor et al. describe how a Scandinavian coffee roaster trademarked the DT label and regulates its use by other firms [6].

Our paper differs from MacGregor, et al.’s (2017) study in one substantive and three methodological ways. Substantively, we focus specifically on DT label use as a marketing strategy rather than on the “voluntary standards” that the label purports to describe. As MacGregor, et al. find, motivations for sourcing coffee directly can differ substantially from motivations for using the DT label, and examining these differences sheds light on the challenges and opportunities associated with DS as a practice and DT as a label. Methodologically, we analyze data from a larger and more diverse sample of organizations: 11 US-based coffee roasters. In addition, we also consider perspectives of representatives of three other coffee stakeholder organizations. Of the roasters interviewed, six use the DT label to varying degrees, and five do not use the label—though they do engage in DS practices. Also, we eschew a cross-national comparison in favor of achieving analytical depth in the US specialty coffee sector. Further, while MacGregor, et al. disclose the identities of the firms in their sample, we provide our interviewees confidentiality with the aim of soliciting greater frankness in their responses.

2. Literature Review

Few scholars explicitly investigate DT; however, extensive research considers standards and certification generally—and sustainable and ethical labeling in coffee specifically [1,2,3,5,14,16,17,18,19,20]. As mentioned earlier, DT is a “top down” or “supply-driven” label developed by industry rather than by activists or farmers [16]. Yet, it differs from firm-specific self-certification schemes, such as Nestlé’s AAA Sustainable Quality or Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Standards, in that its application is industry-wide [16]. Because it is not trademarked, roasters may choose to use the DT label rather than self-certify a sourcing approach. Further, small roasters may benefit from using a label some customers are familiar with rather than starting their own label.

DT’s early adopters set similar standards for their activities, and some of our interviewees still consider Intelligentsia Coffee’s standards to be the best DT approach. Intelligentsia’s website identifies its Direct Trade “criteria” as such:

- “Exceptional coffee quality is a must.

- The grower must be committed to sustainable environmental and social practices.

- The price paid to the grower or local co-op must be at least 25% above the Fair Trade price.

- All trade participants must allow transparent financial disclosures back to the individual farmers.

- Intelligentsia team members must visit the farm or co-op a minimum of once per harvest season. More often, visits will take place three times per year: pre-harvest, mid-harvest, and post-harvest [21].”

However, few other roasters publish their DT standards [6]. Because of the lack of third-party certification, it is difficult for consumers to verify roasters’ claims [2,22]. As such, DT is similar to other sustainability labels such as “local” or “humane” that do not have widely agreed-upon definitions or third-party certification [22,23]. Yet, unlike these labels, DT is not a term used in common speech and may be less intuitive to consumers.

In terms of its goals (improved farmer income, specifically) and its name itself, DT is similar to Fair Trade. Indeed, DT is often discussed in relation to Fair Trade, which has a stringent set of requirements for minimum prices and price premiums, but which has historically had quality control problems [24,25]. DT might be alluring for roasters who want to treat farmers well, but also want high-quality, specialty coffee and deep knowledge of the coffee’s origins. Rather than abide by (and pay for) Fair Trade certification standards, DT roasters could directly forge relationships with farmers, pay them negotiated prices, and ensure they receive the best coffee. Some roasters, however, such as Intelligentsia included paying above Fair Trade prices in their DT standards [21]. See Table 1 for a comparison between DT and Fairtrade International, the most common Fair Trade certification [1].

Table 1.

Comparison between Direct Trade and Fairtrade International.

The lack of third-party certification creates a situation in which DT labeling use is free and unregulated, likely incentivizing late-adopting firms to free ride on the sustainability efforts of early-adopting firms that are following the initial DT standards. Ostrom (1990, p. 6) describes free riding as the situation in which “one person cannot be excluded from the benefits that others provide” and “each person is motivated not to contribute to the joint effort, but to free-ride on the efforts of others [29].” Early in DT’s history, when a handful of roasters used the label, it would have been relatively simple for label users to ensure that other users were maintaining similar standards [7]. However, as the number of DT label users has increased, it has become difficult for roasters that use stringent DT standards to know whether other roasters are free riding on the label. Free riders may decrease the value of the DT label, both by reducing customer confidence and by degrading the reputation of companies that use DT in the eyes of their competitors, colleagues, and consumers. Perversely, a degraded label may harm higher quality roasters more than low quality roasters (including free riders), because high-quality roasters may face higher reputational risks if their brand is built on quality or direct sourcing.

Certification is an important consideration because of DS coffee’s credence qualities. Credence goods embody certain non-monetary values by virtue of the nature of their production process, but they do not differ from other (non-credence) goods in form and function [22,30]. That is, DT coffee does not look, smell, or taste differently from other coffee because it is DT. It is difficult for customers to know whether the product they are consuming is what the seller says it is, and there is an incentive for fraud by sellers [22]. Akerlof’s seminal 1970 paper on the “market for lemons” describes what happens when a low-quality good enters a market and consumers have no way of differentiating high-quality goods from low-quality ones; briefly, the latter drive out the former [31]. For credence goods, certification give customers confidence that they are getting what they want by providing an incentive for firms to be honest [22,30]. If certification increases consumer confidence and they purchase more of a certified product, or purchase it at a higher cost, it also can induce firms to produce more of that good [32]. The combination of DT’s credence qualities and the lack of certification means that there is an opportunity and incentive for firms to “free ride” on the DT label.

Yet, certification is not a panacea for verifying a good’s credence qualities. This is because of the structure of some third-party certifications and empirical evidence on how standards actually perform on their stated goals. As private standards became a primary means to ensure food safety and quality in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, scholars analyzed benefits of and problems with third-party certifications of these standards [1,14,16,18]. Threats to the effectiveness of third-party certification include a potential lack of operational independence of certifiers [14], weak take-up if the certification is not cost-effective [18], and insufficiently stringent standards [1,16].

There also are questions about the practical effectiveness of the standards being certified. In a systematic review of sustainability certifications across value chains, Oya, et al. find no overall net positive effect of certification schemes on farmer incomes, but rather find that their effects are context- and crop-specific [19]. On coffee specifically, few studies are designed to allow for robust causal inference; however, available evidence suggests that certifications can have positive effects on coffee farmer welfare [5]. Specifically, some certifications—such as Fair Trade—come with price premiums, which can help increase farmers household income in some contexts but not in others, perhaps because of high certification costs [5]. In short, while third-party certification can help verify the credence qualities of goods such as DT coffee, they are not without limitations. Their effectiveness depends both on the design of the certification and the design and context of the underlying standards being certified.

Another challenge with DT is that there is little data on its effectiveness when it comes to increasing farmer income. One of the few evaluations of “relationship coffee” sourcing mechanisms (a type of DS) in Colombia finds that farmers did not receive higher incomes from this sourcing approach than other farmers, but they did receive other benefits such as improved access to credit [10]. They also adopted more sustainable resource management systems, which may benefit them in the long term [10]. In addition, farmers who participated in this approach were more optimistic about their investment in coffee than other farmers [10]. Projects conducted by Catholic Relief Services in Latin America—particularly in Colombia—have shown the positive effects of DS on smallholder farmer market access, but these projects do not seem to have resulted in scholarly publications [33]. Indeed, the question of whether and to what extent direct sourcing coffee helps smallholder farmers is hotly debated in coffee trade publications and by international development practitioners. A series of articles by Weissman in coffee trade website Sprudge questioned the effectiveness of DT in increasing farmer incomes [15,34,35] and the Catholic Relief Services’ Coffeelands website has dedicated substantial space to this issue [25,36,37,38].

While little data is available on the effectiveness of specialty-roaster driven DS coffee, there is a relevant literature on contract farming. In contract farming, buyers hire farmers to produce a good based on certain standards, with the guarantee of sale. As Ragasa, Lambrecht, and Kufoalor note, contract farming can range in the level of restriction it places on farmers from something resembling spot markets on one end to near-vertical integration on the other [39]. Like DS, these relationships often involve “cutting out the middleman” so that the buyer can access the quality they want and have better information on the process. The literature is inconclusive about the effectiveness of buyer-driven value chain upgrading in improving farmer well-being. There is evidence that it can increase farmer income [40,41,42,43,44], but that (1) it tends to exclude the poorest farmers [40], (2) effectively implementing contract farming on a large scale can result in farmers being “captured” by a buyer and having few other sale options [45] and, (3) that the opportunity costs of engaging in contract farming can be high, in terms of less income coming from non-farm activities [43]. A cautious interpretation of evidence on contract farming suggests how farmers fare in contracting farming relationship with buyers is likely context and value-chain specific.

Importantly, the roasters interviewed for this study are quite dissimilar to the multinational corporations involved in large-scale contract farming. They are much smaller and aim to work collaboratively with smallholders or cooperatives to produce high-quality coffee. They generally do not have the ability to enforce monopsonistic buying, though it is true that the poorest coffee farmers may be unable to produce high enough quality coffee to sell through a DS channel. Direct sourcing adopters believe—based on their own experiences and relationships with farmers—that DS can help farmers. However, as noted in Section 5.3, more research is needed on the effects of DS on farmers to support these claims.

A final challenge to the DT label is the recent proliferation of similar labels. Over the past few years, other variations of DT have sprung up: Whole Foods’ “Whole Trade,” Land of a Thousand Hills’ “Collaborative Trade,” and Simpatico’s “Farmer Direct,” among others [46,47,48]. Given the challenges that consumers face in understanding and comparing sustainability labels, DT may be difficult to differentiate from third-party certified labels such as Fair Trade as well as from firm-specific labels and self-certifications [2]. In addition, many roasters and cafes use images and descriptions of farmers that imply a relationship with these farmers, whether or not that is the case. Thus, it may be difficult for consumers to understand how DT is different from the relationships with farmers that roasters and cafes imply.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Design

In this study, we qualitatively analyze interviews conducted with a sample of coffee roasters to address our research questions. In addition, we analyze interviews with coffee stakeholders to triangulate with roaster responses. In identifying respondents, we used a purposive sampling approach, which relies on researchers’ knowledge and secondary sources to develop a sample [49]. Company websites and coffee blogs specifically provided information on which companies are most dedicated to DT or DS (if not specifically labeled as DT). We identified and contacted 20 US specialty coffee roasters between September 2017 and March 2018. We aimed to interview a geographically broad mix of roasters across the US, and our sample of 11 included three roasters in the Eastern US, four in the Midwest, and four on the West Coast. All but one practice DS, even though not all use the DT label. Among the 9 DS roasters we contacted, but who did not agree to be interviewed, 4 use the DT label.

To maintain confidentiality, we describe roasters by their company size (small, medium, and medium/large) and assign a number to each roaster, as seen in Table 2. We asked roasters how much coffee they roasted per year to categorize companies by size. We define small companies as those roasting 1–299,999 pounds of coffee per year, medium companies as those roasting 300,000–599,999 pounds per year, and medium/large companies as those roasting 600,000 or more pounds per year. Note that size categories have been developed based on sampled roasters, and these are not representative of roaster sizes across the coffee industry. Multinational coffee companies roast substantially larger volumes of coffee. For example, in 2014, Starbucks roasted approximately 500,000,000 pounds of coffee—over 166 times as much coffee as the largest roaster in this sample [50]. By comparison, the largest company in our sample roasts about 3,000,000 pounds of coffee per year. When considering the direct relationship between roasters and farmers, it is important to note that even the largest companies interviewed are not multinationals. Thus, their engagement in DS may differ from a larger company that directly sources from farmers.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics.

To supplement our interviews with these 11 roasters, we also conducted interviews with three other coffee stakeholders. These interviews provide broad sectoral context and can be used to triangulate findings from roaster interviews. Stakeholders include representatives of two specialty coffee non-profit organizations and one importer that imports coffee using socially responsible protocols. These three other coffee stakeholders, each of which are based on the West Coast, work closely with DT roasters and provide a high-level view of how DT fits into the US specialty coffee industry. Perspectives of these stakeholders are summarized in Section 4.4.

3.2. Interview Approach

We used a semi-structured format to interview all respondents. That is, we asked each participant the same core questions, and we included additional follow-up questions based on their responses. Our interview sessions ranged from 30–75 min, with most approximately 50 min.

We told key informants that their names and their company names would be kept confidential. With their authorization, we recorded interviews digitally and then transcribed and coded these transcripts. We conducted all interviews over the phone or Skype. To supplement our interview data, we also analyzed publicly available information, such as content available on our sampled coffee roasters’ websites.

3.3. Coding Process

We developed a codebook for analysis based on the relevant literature, our research questions, and emergent themes from interview responses. We identified themes and noted their frequency and intensity as discussed by interviewees. We also recorded areas of agreement and disagreement between roasters. Finally, we identified quotes from interviews that were illustrative of perspectives expressed by multiple respondents.

3.4. Description of Interviewed Roasters

Table 2 provides information on the relative size of roasters, their DS level, and their use of the DT label. For the DS level, based on the interviews, we developed a three-point scale to categorize sourcing directness regardless of whether roasters use the DT label. Intensive DS includes or exceeds the Intelligentsia DT standards, which are the most commonly referenced standards in our interviews. The six roasters in this category negotiate price and quality with farmers, travel extensively to meet with farmers, and have long-term relationships with them wherein they help farmers experiment and improve coffee quality.

In the Some DS category, four coffee roasters maintain some relatively direct relationships with farmers, while others are mediated by coffee importers. These roasters inconsistently use the DT label with their DS relationships. Their knowledge of the prices paid to farmers varies; they sometimes travel to meet with them but at times simply meet with importers. In the No DS category, roasters buy from importers, they do not travel to meet with farmers, and they do not know the prices paid to them. This last designation only applies to one roaster, who nevertheless does use the DT label.

With respect to DT labeling, in our sample four roasters consistently use the DT label. Another two roasters use it inconsistently in some marketing materials, but not others. In both cases, their websites referenced DT, and we used that to identify them for interviews. Yet, during each interview, the key informants said that they tried not to use the label. Four roasters have never used the DT label. One roaster used the DT label previously but no longer does so.

4. Results

4.1. Motivations to Source Coffee Directly from Farmers

Table 3 displays the main results for our first research question about what motivates coffee roasters to source coffee directly from farmers. Many roasters believe that DS not only is good for coffee quality and consistency, but also is positive for farmers—an important value for roasters. All six roasters who use intensive DS say that it provides high-quality coffee. Six roasters (five intensive DS, one some DS) also say that farmers benefit from DS. In Table 3, we describe two broad categories of roasters’ motivations for sourcing coffee directly from farmers. Within each category, this Table contains each constituent theme and an illustrative quotation.

Table 3.

Motivations for Sourcing Coffee Directly from Farmers.

4.1.1. Business Motivations

All roasters deeply engaged in DS stated that DS provides roasters with higher quality coffee than they would otherwise receive, confirming an earlier finding by MacGregor et al. [6]. According to these roasters, DS also allows for direct communication, experimentation, long-term relationships, and opportunities for offering higher prices for quality beans. One roaster suggests that purchasing coffee from agronomic and processing experiments that do not work (i.e., do not produce the desired quality or quantity of coffee) provides a sort of insurance for farmers who may otherwise be risk averse. In addition, purchasing directly from farmers rather than from coffee importers allows roasters more information on and influence over coffee production and processing.

Importantly, DS helps to facilitate quality segmentation at the farm level. This involves dividing coffee into multiple tiers and paying different prices for each segment rather than mixing them and paying a single price. It allows roasters to receive higher quality coffee, and farmers to receive higher margins. Several roasters see quality segmentation as a mutually beneficial arrangement between them and farmers and key to why DS works. Roaster 2 suggests:

“…We think of coffee as a pyramid…Relatively little of the best coffee, and there is a lot of the worst coffee. The better the coffee is, the less there is available. That scarcity is what drives the value. I personally believe in segmentation and that is the heart of the (company) sourcing model. Segmentation with an eye to quality-based differentiation and access to specialty markets.”

4.1.2. Social Responsibility Motivations

Roasters also source directly because their personal and corporate beliefs encourage them to work directly with farmers. Roasters describe values related to farmer well-being and believe that DS is beneficial to farmers by increasing their income, increasing their trust with roasters, and helping them learn new farming and processing approaches. Of these, roasters most often cite increased farmer income. Specific mechanisms for increasing income include the ability to market coffee as specialty grade and improved information about coffee quality and available prices.

Two intensive DS roasters are ambivalent about the effects of DS on farmer income, noting that high prices do not always translate into higher incomes to farmers. Not all coffee produced by farmers who sell through a DS arrangement sells for high prices, and their costs of production can increase if they are changing their production practices to meet roaster quality needs.

Roasters fluctuated between discussing their personal values and describing their company values. Even though their companies are economically rational, profit-maximizing firms, several roasters state that they want to treat farmers and other actors along the value chain well even if it would reduce their company’s bottom line. Roaster 8, for example, sees their sourcing model as differentiating them from bad “capitalist” companies, who, according to him, exploit farmers while focusing exclusively on profit.

That roasters use DS despite the numerous challenges associated with it speaks to how important they view this approach. Difficulties noted by roasters include financial cost, time out of the office, trouble in accessing consistently high-quality coffee, stress from conflict with farmers with whom they have close relationships, and the physical strain of frequent traveling.

4.2. Motivations to Communicate Sourcing Practices to Customers (Inclusive of Using the DT Label)

Table 4 displays the main results for our second research question about what motivates coffee roasters to communicate sourcing practices to their customers. Roasters generally believe that doing so is important both extrinsically (e.g., they think sharing it will help sales) and intrinsically (e.g., they want to tell compelling stories about sourcing for personal reasons).

Table 4.

Motivations to Communicate Sourcing Practices.

Roasters think critically about how they communicate about sourcing. Many believe that their customers are generally uninformed about sourcing, and that they would more accurately perceive the value of their coffee if they understood more about its sourcing. If DS really does help farmers, then getting customers this information is important. This is a rationale for using the DT label; it provides information that would be difficult otherwise to share with customers (who might not know much about coffee sourcing).

As noted, many roasters believe that customers would buy more if they understood the ethics and work that have gone into directly sourcing coffee. The only roaster who said that customers would not buy more is Roaster 7, who uses the DT label but does not use DS practices.

4.3. Motivation Not to Use the DT Label, Despite Using DS Practices

Table 5 displays the main results for our third research question about what motivates coffee roasters to not use the DT label even when using DS practices. The DT label was designed to provide information to customers about sourcing practices. If effective, it should convey to customers valuable information that shapes their views about a roaster and their subsequent purchasing behavior. Yet, many roasters who practice DS do not use the DT label, use it inconsistently, or see considerable challenges with it. Interviewees (both those who use the label and those who do not) conveyed three major problems with the DT label: (1) it is unclear; (2) it is unnecessary; and (3) it is devalued by free riders.

Table 5.

Reasons Not to Label DT or Challenges with the DT Label.

4.3.1. The DT Label is Unclear

Even though respondents accurately state that there is no official industry definition of DT, most roasters describe commonly perceived features (e.g., roasters and farmers negotiate price and quality, visit with farmers, etc.). This may be because early adopters, who were well known to most interviewees, published their standards. Yet, while most interviewees share a basic understanding of what DT means, they realize that they cannot force other roasters to abide by it. Five roasters who do not use the label or use it inconsistently suggest that a lack of clarity is a problem with the DT label. This lack of a shared, enforceable meaning may erode the DT label’s value. A roaster who moved away from DT notes,

“It became very murky.(In the) public sphere and usage of that phrase. That terminology became very clouded. And so this kind of coincided with us focusing more and more on transparency within our supply chain.” (Roaster 1).

4.3.2. The DT Label is Unnecessary

Roasters provide several reasons for why the DT may be unnecessary. Some do not believe that their customers care much about sourcing. In addition, some roasters suggest that they have other ways of communicating about sourcing that they like better. For example, some prefer to tell detailed stories about the farmers from which they source. Of the four roasters who specifically said that they did not label because the DT label was not necessary, two practice intensive DS and two practice some DS. None label DT. In explaining why they do not see the DT label as necessary and what they prefer to do instead, Roaster 9 says:

“It is not that we sit around and discuss whether this year we need to start using Direct Trade. Now that the vast majority of our coffees are sourced collaboratively. But we are not having those conversations. Conversations are more (about) ‘how to do we get people to appreciate specific coffees?”

Supporting their belief that the label may be unnecessary, most roasters believe that customers do not understand DT very well. Some roasters who use the DT label think customers have a sense about, or can infer, what it means. However, others think that most customers probably would misunderstand what DT means because of their low level of knowledge about coffee. Roasters generally expect that customers would see DT primarily as an ethical signal and secondarily as a quality signal. Roaster 10, which uses the DT label, says,

“I think they think that Direct Trade—it means that I went down there and said ‘we are deciding on $4 a pound, and you get all that $4 a pound.’ They also think that farmer X is picking all the coffee and busting his ass day in and day out and they also assume that they are really poor… And it is completely devoid of any influence from the C market. If they have heard of the C market. Maybe nobody calls it the C market. But devoid of this mythic evil establishment thing.”

The “C market” refers to coffee futures price, as traded in the New York Coffee, Sugar, and Cocoa Exchange [51].

4.3.3. Free Riders Harm the DT Label

Four roasters who do not use the DT label believe it is common for others to “free ride” on the DT label or use the label while not following the practices generally agreed upon as Direct Trade. In addition, two roasters who inconsistently use DT see this as an issue, and one roaster who continues to use the label is considering dropping the label for this reason. Finally, one roaster in our sample (Roaster 7) appears to be free riding the DT label, in that they use the label but not DS practices. This roaster did not see their labeling as incongruous with their sourcing approach, because they said the importer they purchased from knew the farmers.

Roasters often discuss concerns about free riding in the context of describing the variety of practices that they have seen labeled as DT. Roaster 3, which uses the DT label, expresses concern about doing so in light of the free rider problem:

“Yeah, we are still 100% committed to principles of what we are doing. It is less about the brand name Direct Trade. I don’t care about that. It is about the process of buying coffee. We have actually considered changing and rebranding away from Direct Trade. The Direct Trade words have been co-opted and cheapened.”

Roaster 6, which does not use the DT label, further describes the free rider problem:

“Where I have a problem is with the ease of saying “I do Direct Trade because I went on an origin trip and I met a producer and I’m buying his coffee every year.” Oh wow, it’s that simple. Piggybacking on the efforts of companies that put some meat behind it. I do have some moderate issue with that… These companies are doing all these things to show that what they are calling Direct Trade is really a thing and you’re just riding that train without putting in the work and the resources. But because you can do that and no one is stopping you, no one is suing you, “cool, good for you.”

4.4. Other Stakeholder Perspectives on DT and DS

We interviewed three other coffee stakeholders who are experts in the sector and have personal familiarity with DS and the DT label. The purpose of interviewing them was to gain additional perspectives on the structure and viability of the DT label from experts who were not roasters and triangulate their perspectives with findings from interviews with roasters. In this section, we briefly summarize their perspectives on the issues discussed by roasters. They cannot speak to roasters’ motivations but can provide perspectives on the benefits of sourcing directly and of communicating sourcing practices to consumers, as well as challenges with the DT label. Stakeholders generally agreed with, and in some cases added nuance to, roasters’ perceptions about DS and DT.

4.4.1. Benefits for Sourcing Directly

All three stakeholders spoke positively about DS, though less so about the DT label. Two stakeholders agree with roasters that quality is a primary benefit of DS. One adds that predictability of quality is a benefit. All stakeholders value the potential social benefits of DS to farmers. While one suggested that they cannot guarantee that DS increases farmer incomes, they believe that the model is helping farmers.

4.4.2. Communicate Sourcing Practices to Customers

Two stakeholders agree with roasters that customers likely do not understand DT, but believe that customers likely see it as an ethical label. One stakeholder suggests that a benefit of a label like DT is that it is simple, and notes that customers generally do not read long sustainability reports. Echoing roasters’ concerns about customer perceptions about DT, Stakeholder 2 says:

“Direct Trade is being used a lot. I think it is being used and interpreted by consumers as “Oh good, you are treating the farmer well and they are getting a good price.” So they are making a lot of assumptions that you could make safely in the past with Fair Trade documentation.”

4.4.3. Challenges with DT label

These three other stakeholders had concerns about the DT label. Two said the label is not clear; a third went farther and said the label is meaningless without third-party certification. They also suggested that there is the possibility for free riding, and that a wide range of practices are labeled DT. It is important to note that interviews with importers show that they see DT as a threat to their business, insofar as DS can reduce the role of importers in the value chain. However, there was agreement by stakeholders about problems with the label. Stakeholder 2 said that: “There is no standard. Like I said, it’s the same as saying “natural flavoring” or “natural.” It doesn’t mean anything because there are no standards.”

5. Discussion

5.1. DS Roasters’ Decision-Making Model

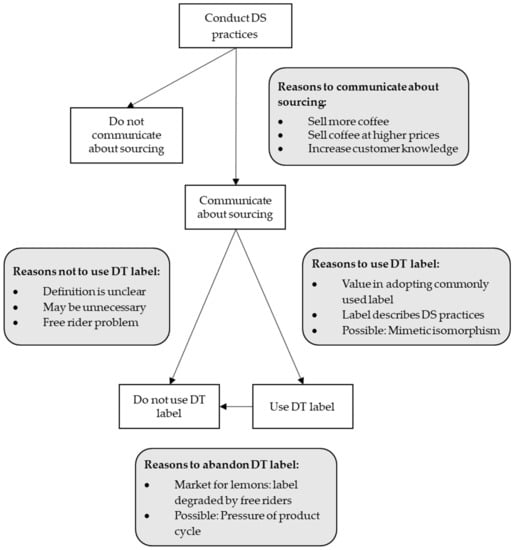

Incorporating the above results, Figure 1 presents a path model for explaining DS roasters’ decisions about communicating sourcing to customers and about using or not using the DT label. DS roasters’ decisions about using or not using the DT label are influenced by their assessment of the benefits and drawback of the label itself. If roasters express considerable concern about the problems with the label, then they may forego it entirely, choosing instead to convey to customers the values inherent in DS practices via other means (e.g., telling stories about their DS relationships with farmers).

Figure 1.

Decision-Making Model for Explaining Why DS Roasters Communicate about DS and Whether or Not They Use the DT Label.

Yet, often DS roasters adopt a DT label to communicate their direct sourcing practices. Such a decision is expected given a neo-institutionalist argument about “mimetic isomorphism” [52]. Briefly, according to this argument, organizations facing uncertain institutional environments (in this case, roasters in the specialty coffee industry) mimic structures and practices used by more successful organizations—resulting in organizations becoming more similar to each other over time [52]. In other words, as early creators of the DT label help to popularize its use in the industry and enhance its legitimacy in the eyes of customers, other DS roasters are incentivized to also adopt it to increase their own legitimacy.

Over time, however, problems may emerge. Some roasters—who may use DS only haphazardly or not at all—may free ride the DT label to gain legitimacy in the industry and among customers. At the same time, the value or legitimacy of the DT label may be diminished by the “product cycle” of specialty coffee itself [14,53]. As a sourcing approach goes from being unique and niche to becoming conventional and mainstream, high-end roasters face pressure to innovate further to continue to distinguish themselves from competitors. In doing so, high-end roasters may justify the higher prices for their specialty coffee relative to those for conventional coffee.

While some roasters may be free riding the DT label, others may be experimenting with alternative labels and branding. The preponderance of new sustainable sourcing labels may lead to continued fragmentation, with consumers becoming less able to distinguish between real and fraudulent sustainability claims. Such a situation creates a “market for lemons,” where low-quality commodities drive high-quality commodities out of the market [31]. The DT label will become diminished in the minds of roasters, with some or many abandoning the label—even those who continue to employ rigorous DS approaches.

The upshot of all of this is that mimetic isomorphism, free riders, and the product cycle help explain the movement of small roasters into DT labeling, the subsequent movement of early DS adopters away from DT labeling, and the incentives for other innovative firms to avoid DT labeling and instead tell detailed stories about their DS approach and practices.

5.2. Possible Solutions: Third-Party Certification and Shared Self-Certification Standards

Specialty roasters see value in customers knowing about their sourcing practices. It is also possible, though not proven, that the DS model in specialty coffee improves farmer incomes. Because of the non-credence qualities of DS coffee (high quality, unique origins, etc.), it is possible that roasters will continue to purchase DS coffee and deliver benefits to farmers even if the DT label goes away. However, if roasters are correct that customers would buy more or pay more for DS coffee if they had more information, roasters may be missing opportunities to expand DS activities and provide the social benefits described by these activities. Studies on the effects of sharing sourcing information with customers suggest that it can be effective in increasing the perceived value of food products, which supports roasters’ beliefs about customer knowledge [13,54,55]. The lack of an agreed upon label also means that consumers do not have a way of determining which coffee companies’ claims to believe, and the burden of verification now falls on consumers [6]. From an efficiency perspective, the high costs of information about sourcing processes might produce an inefficiently low volume of DS coffee on the market and an inefficiently high volume of conventional coffee [32]. If there are benefits of DS for low income farmers, this could also hamper farmers’ abilities to increase their incomes through long-term partnership with roasters.

Might a certification system help ameliorate these challenges? Given the structure of DT—a top-down sustainability label shared by numerous companies—we explore two possible ways of dealing with the label’s credence qualities: (1) third-party certification and (2) an agreed upon industry standard that roasters use to self-certify.

Third-party certifications are common for sustainability standards and can be effective in verifying the credence qualities of goods [22]. We asked roasters in our sample about whether they supported third-party certification for DT; seven roasters supported the idea. They agree that it might provide a clear definition of DT and also might increase the costs of free riding. However, two respondents express concern that a third-party certification scheme could be costly and might not substantially aid farmers, either because farmers might need to pay for certification or because the benefits of certification might accrue more to roasters than to farmers. Two other roasters also worry that such a scheme might produce a “least common denominator” standard that many could reach, but which would be less strict than their current sourcing approaches. These roasters suggest that their rigorous standards would be difficult for many other roasters to implement, implying that a scalable third-party certification scheme would necessarily be much less rigorous.

One reason that a third-party DT certification system has not emerged may be the lack of an interest group advocating for it, as noted by Roaster 6. The DT label is supply-driven [12,18] and not “demand-driven.” For the latter, there often is an external interest group advocating for sustainability standards. While most respondents favor third-party DT certification, it is unclear whether they are concerned enough to invest in developing such a certification. This represents a collective action problem, in which all roasters who use DS practices could benefit from external verification, but it is not in any one company’s interest to take the lead in organizing (and paying for) a third-party verified standard. However, it may be possible to develop a third-party verification system if the costs of creating such a standard are lower than the losses DS roasters might incur if customers do not trust their sourcing claims.

If a third-party certification system is preventatively costly, there may be an alternative standards scheme that would be stronger than the status quo, but would be less costly (and weaker) than third-party certification. With this alternative, a group of roasters would agree on shared standards, which then could be published on the websites of any company that wants to use the DT label. Such a DT standard system would entail self-labeling, but with the standard formalized by a consortium of companies rather than by a single company. This approach would be similar to second-party certification, which as Raynolds, et al. (2007, p. 149) note “involve(s) industry associations. establishing standards or verifying compliance” [16]. While it could be overly expensive for roasters to monitor each other to ensure they are doing what they say, simply having to agree to shared standards might create a barrier to entry for companies that do not source directly. This approach also could provide customers with more information about what DT means, even if they are unable to verify that each roaster using the label does what they claim. Standards could take inspiration from an existing standards approach, such as Intelligentsia’s Direct Trade standards or illy caffe’s Responsible Supply Chain Process, which includes direct sourcing as part of a holistic sustainability standards approach [21,56]. Longoni and Luzzini credit illy’s Responsible Supply Chain Process with developing social capital along the coffee value chain, and thereby using a DS model to empower farmers [56].

Little research has focused on uncertified standards arrangements between agricultural firms, though studies have described varying degrees of success in environmental self-regulation [57,58]. Examples in agricultural commodities may be uncommon because of the high likelihood of free riding when there is nobody verifying claims regarding sustainability practices and when numerous firms work in diverse locations and cannot easily observe each other [59]. In the case of DT, an uncertified standards system would be a second-best option compared to third-party certification, because free riding would be easier. However, given that the status quo is no shared definition or certification, an agreement on a DT definition and standards by roasters could be a step toward a label that provides useful information about sourcing to consumers in the long term.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

There are some limitations to this study, which relate to how the findings should be interpreted. First, there is no registry of DT roasters and it is impossible to know exactly how many roasters use the label. Even harder is identifying roasters who use DS approaches but do not label—as noted, the sourcing practices of non-labeling roasters are difficult to ascertain. Also, for this study, we only work with US roasters. Thus, we must be cautious about the extent to which we can extrapolate results to the US specialty coffee industry, or even US roasters who use DS practices.

Second, this paper describes roaster perceptions of both their motivations and the impact of their sourcing decisions. This is especially important as it relates to two issues: the impact of DS practices on farmer incomes and well-being, as well as customer knowledge of and demand for DT coffee. It is important to study both whether existing DS practices (whether or not they are labeling DT) are effective, and under what circumstances they might be effective.

In addition, though there have been several studies on customer demand for sustainable coffee more generally [13,60,61], to our knowledge no studies have focused on demand for DT coffee. Analysis of customer demand for DT coffee can shed light on an important issue related to how viable the DT label is in the long term as a sustainability label. An important question is whether Fair Trade and DT are competing sustainability labels or if they attract different customer bases. If they are competing labels, losing the DT label would be less of a problem. Ethical consumers could instead buy Fair Trade coffee, which guarantees a minimum price and price premiums, and consumers who want high-quality micro-lots might end up buying DS coffee because they enjoy the flavor. However, if there are consumers who specifically value the DS structure—perhaps for a combination of ethical considerations and quality—losing the DT label may reduce their ability to purchase their preferred coffee and reduce the incentive for roasters to source directly. In short, additional analysis is needed to explore the relationship between DT consumers and their coffee.

6. Conclusions

We explored specialty coffee roasters’ motivations to (a) source coffee directly from farmers, (b) communicate about their sourcing practices, and (c) use or not use the DT label. We found that roasters source directly from farmers primarily for business reasons, but also for their ethical concern for farmers’ well-being. Further, we found that roasters communicate their sourcing practices to customers for several reasons, which range from extrinsic motivations (e.g., the potential for greater profit via increased sales and/or prices) to more intrinsic motivations (e.g., a desire to share the value of their work with customers). Finally, we found that roasters’ concerns about the DT label’s clarity and necessity and about free riders heighten disenchantment with the label and increase the likelihood that roasters will not use it.

There currently exists no third-party DT certification scheme to address challenges with definitions, compliance, and free riders. While such a scheme—which is not without its weaknesses—may be desired, one is unlikely to emerge in the near future due to the lack of an independent advocacy organization invested in its creation. In its stead, one potential alternative to the status quo is the creation of something akin to the second-party certification of DT self-labeling. This would convey considerable DT information to customers while also reducing the likelihood of free riders.

Author Contributions

A.G. was engaged in the conceptualization, methodology development, investigation, analysis, and writing of this article. M.C.L. and A.M. were involved in the methodology, analysis, and editing of this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the interviewees for their generosity in speaking with us. They would like to thank John Kerr and Daniel Clay in the Department of Community Sustainability and Steven Gold in the Department of Sociology at Michigan State University for reviewing an earlier draft of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dietz, T.; Auffenberg, J.; Estrella Chong, A.; Grabs, J.; Kilian, B. The Voluntary Coffee Standard Index (VOCSI). Developing a Composite Index to Assess and Compare the Strength of Mainstream Voluntary Sustainability Standards in the Global Coffee Industry. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, D.; Ponte, S. Standards as a New Form of Social Contract? Sustainability Initiatives in the Coffee Industry. Food Policy 2005, 30, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, J.; Manning, S.; von Hagen, O. The Emergence of a Standards Market: Multiplicity of Sustainability Standards in the Global Coffee Industry. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 791–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynolds, L.T. Mainstreaming Fair Trade Coffee: From Partnership to Traceability. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.A. What Are We Getting from Voluntary Sustainability Standards for Coffee? Center for Global Development, Policy Paper 129: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, F.; Ramasar, V.; Nicholas, K.A. Problems with Firm-Led Voluntary Sustainability Schemes: The Case of Direct Trade Coffee. Sustainability 2017, 9, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M. God in a Cup: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Coffee; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, E.; Kjeldsen, C.; Kerndrup, S. Coordinating Quality Practices in Direct Trade Coffee. J. Cult. Econ. 2016, 9, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, S. Direct Trade: Going Straight to the Source. Available online: http://www.scanews.coffee/2012/02/14/direct-trade-the-questions-answers/ (accessed on 11 February 2017).

- Hernandez-Aguilera, J.N.; Gómez, M.I.; Rodewald, A.D.; Rueda, X.; Anunu, C.; Bennett, R.; van Es, H.M. Quality as a Driver of Sustainable Agricultural Value Chains: The Case of the Relationship Coffee Model. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C. Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Can Fair Trade, Organic, and Specialty Coffees Reduce Small-Scale Farmer Vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua? World Dev. 2005, 33, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviron, B.; Ponte, S. The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Lotade, J. Do Fair Trade and Eco-Labels in Coffee Wake up the Consumer Conscience? Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, M.; Busch, L. Third-Party Certification in the Global Agrifood System: An Objective or Socially Mediated Governance Mechanism? Sociol. Ruralis 2008, 48, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M. Is Direct Trade Fair? Available online: http://sprudge.com/is-direct-trade-fair-110410.html (accessed on 11 February 2017).

- Raynolds, L.T.; Murray, D.; Heller, A. Regulating Sustainability in the Coffee Sector: A Comparative Analysis of Third-Party Environmental and Social Certification Initiatives. Agric. Human Values 2007, 24, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Pelupessy, W. Governing the Coffee Chain: The Role of Voluntary Regulatory Systems. World Dev. 2005, 33, 2029–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, K.B.; Kerr, J. Limitations of Certification and Supply Chain Standards for Environmental Protection in Commodity Crop Production. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C.; Schaefer, F.; Skalidou, D. The Effectiveness of Agricultural Certification in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. World Dev. 2018, 112, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.; Boons, F.; von Hagen, O.; Reinecke, J. National Contexts Matter: The Co-Evolution of Sustainability Standards in Global Value Chains. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intelligentsia. Direct Trade. Available online: https://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/learn-do/community/intelligentsia-direct-trade (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Holland, S. Lending Credence: Motivation, Trust, and Organic Certification. Agric. Food Econ. 2016, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.C.; Salois, M.J. Local versus Organic: A Turn in Consumer Preferences and Willingness-to-Pay. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, C. The Problem With Fair Trade Coffee. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2011, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- CRS Coffeelands. Third-Rail Communications. Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2015/11/third-rail-communications/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Fairtrade America. Coffee. Available online: http://fairtradeamerica.org/Fairtrade-Products/Coffee (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Fairtrade International. Small-scale producer organizations. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net/standard/spo (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Fairtrade International. Fairtrade Standard for Coffee for Small Producer Organizations and Traders; Fairtrade International: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, B.; Sheldon, I. Credence Good Labeling: The Efficiency and Distributional Implications of Several Policy Approaches. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 89, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.F. Certification of Socially Responsible Behavior: Eco-Labels and Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2009, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M. The Path to Distinction: Nurturing Separation in Nariño. Roast Mag. 2016, 4, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M. Show Me the Money: Direct Trade Volume 3. Available online: https://sprudge.com/show-me-the-money-direct-trade-volume-3-123856.html (accessed on 7 September 2019) .

- Weissman, M. Direct Trade in the Shadows. Available online: https://sprudge.com/direct-trade-in-the-shadows-116639.html (accessed on 7 September 2019) .

- CRS Coffeelands. What is the standard for (disclosure in) Direct Trade? Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2011/06/what-is-the-standard-for-disclosure-in-direct-trade/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- CRS Coffeelands. More on Direct Trade standards. Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2011/07/more-on-direct-trade-standards/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- CRS Coffeelands. Research Review: Counter Culture’s Case Study on the Social Impact of Microlots. Available online: https://coffeelands.crs.org/2012/04/research-review-counter-cultures-case-study-on-the-social-impact-of-microlots/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Ragasa, C.; Lambrecht, I.; Kufoalor, D.S. Limitations of Contract Farming as a Pro-Poor Strategy: The Case of Maize Outgrower Schemes in Upper West Ghana. World Dev. 2018, 102, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, G.; Vellema, W.; Desiere, S.; Weituschat, S.; Haese, M.D. Contract Farming for Improving Smallholder Incomes: What Can We Learn from Effectiveness Studies? World Dev. 2018, 104, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolwig, S.; Gibbon, P.; Jones, S. The Economics of Smallholder Organic Contract Farming in Tropical Africa. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, M.; Colen, L.; Swinnen, J.F.M. Globalisation and Poverty in Senegal: A Worst Case Scenario? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F. Contract Farming: Opportunity Cost and Trade-Offs. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minten, B.; Randrianarison, L.; Swinnen, J.F.M. Global Retail Chains and Poor Farmers: Evidence from Madagascar. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C. Contract Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey of Approaches, Debates and Issues. J. Agrar. Chang. 2012, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whole Foods Market. Whole Trade. Available online: https://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/mission-values/whole-trade-program (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Land of a Thousand Hills Coffee. Collaborative Trade Postcards 100/pack. Available online: https://shop.landofathousandhills.com/products/collaborative-trade-locations-postcard (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Simpatico Coffee. Farmer Direct Coffee. Available online: https://simpaticocoffee.com/pages/straight-trade-coffee (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 8th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. How 7 people test 400 million pounds of Starbucks coffee a year. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/3025212/how-7-people-test-400-million-pounds-of-starbucks-coffee-a-year (accessed on 6 September 2019) .

- Ponte, S. Brewing a Bitter Cup? Deregulation, Quality and the Re-Organization of Coffee Marketing in East Africa. J. Agrar. Chang. 2002, 2, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Codron, J.-M.; Busch, L.; Bingen, J.; Harris, C. Global Change in Agrifoods Grades and Standards: Agribusiness Strategic Responses in Developing Countries. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2001, 2, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Delanchy, M.; Remaud, H.; Zepeda, L.; Gurviez, P. Consumers’ Perceptions of Individual and Combined Sustainable Food Labels: A UK Pilot Investigation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, C.R.; Johnston, R.J.; Donath, H. Assessing Consumer Preferences for Ecolabeled Seafood: The Influence of Species, Certifier, and Household Attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 81, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Building Social Capital into the Disrupted Green Coffee Supply Chain: Illy’s Journey to Quality and Sustainability. In Organizing Supply Chain Processes for Sustainable Innovation in the Agri-Food Industry; Cagliano, R., Caniato, F.F.A., Worley, C.G., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, F.E.; Bansal, P.; Slawinski, N. Scale Matters: The Scale of Environmental Issues in Corporate Collective Actions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1411–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Lenox, M.J. Industry Self-Regulation without Sanctions: The Chemical Industry’s Responsible Care Program. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 698–716. [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A.; Janssen, M.; Ostrom, E. Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bajde, D.; Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G.; Winchester, M.; Arding, R.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trader Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2013, 13, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufer, D.; Lin, W.; Ortega, D.L. Personality Traits and Preferences for Specialty Coffee: Results from a Coffee Shop Field Experiment. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).