Backyard Agricultural Production as a Strategy for Strengthening Local Economy: The Case of Chontla and Tempoal, Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

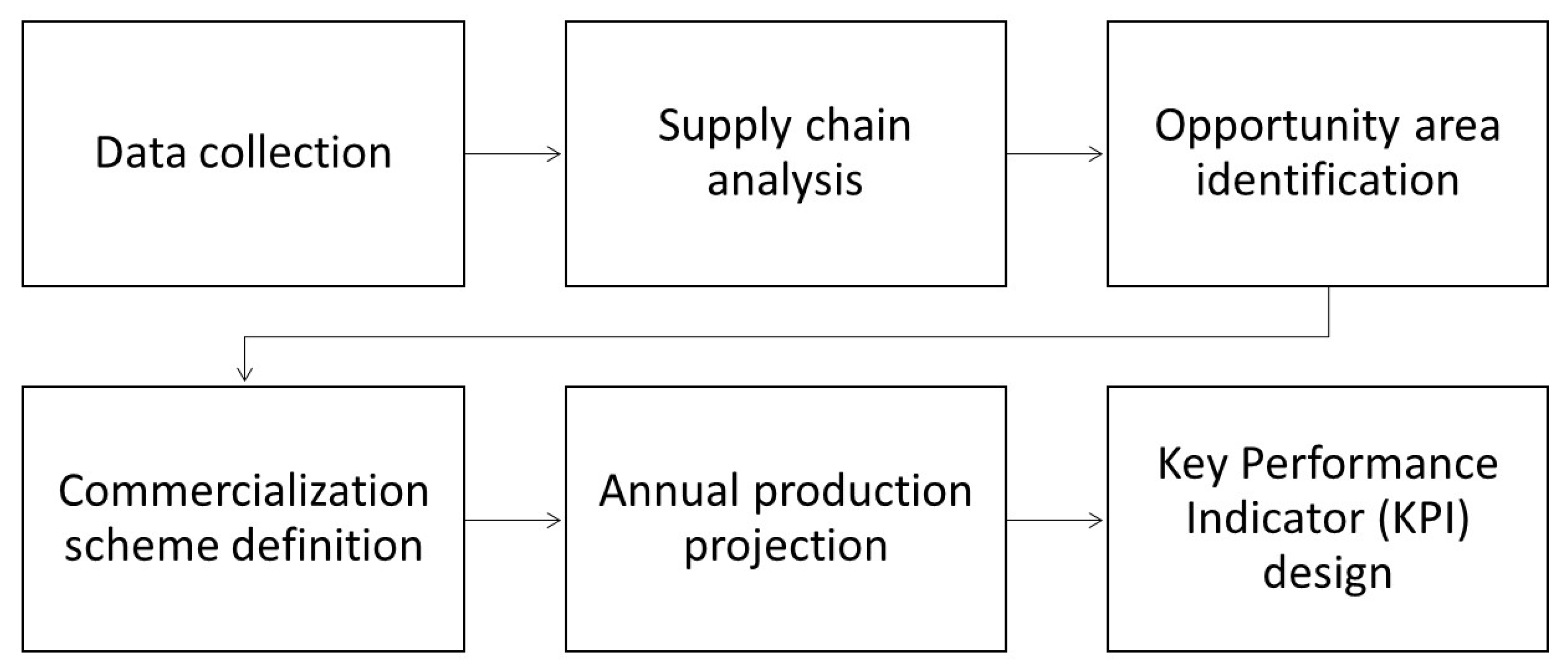

- Data collection. To identify the economic agents and supply chain echelons, face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted with agricultural producers, intermediaries, agents, municipal authorities, wholesalers, and market owners. Also, a survey was designed to identify and quantify backyard agricultural products and their measurement units and production destinations. An opportunity sampling proposed by Hernández et al. [23] was carried out to collect backyard production information according to the operative capacity and economic resources linked to this study, taking advantage of monthly meetings held in the communities by municipal agents to discuss issues about their welfare.

- Supply chain analysis and opportunity area identification. They were defined with face-to-face semistructured interviews to integrate a generic model of the agro-food supply chain proposed by Stringer and Hall in 2007 [19], which analyzes the productive system through supply chain decomposition into hierarchical components (stages, operational steps, and unit operations).

- Commercialization scheme definition. A short productive chain proposed by Rodríguez and Riveros in 2016 [24] was analyzed, which evaluates criteria such as producer organizations, product differentiation, number of intermediaries, business formalization of purchasing and selling products, and social proximity between producers and final consumers.

- Annual production projection. Through surveys and statistical projection, we quantified the volume production destined for sale and self-consumption, and on-site food rot. Unit measurements were identified for each homegrown backyard agricultural product (tree, bucket, roll, quart, piece, grate, and litter) and converted to its equivalent weight in kilograms. The annualized economic value of production was calculated by multiplying the product weight by the harvest amount expected per year by sale price in the local market. To perform these calculations, a computational program designed in PHP 5.4.16 was used, including MySQL 5.5.32 as a database manager.

- Key performance indicator (KPI) design. Backyard agricultural profitability (BAP) is the performance measurement of the backyard agricultural production system that expresses the proportion not sold due to noncommercialized (unused or rotted) products and could be an economic benefit for backyard producers and high development priority communities. BAP KPI can measure the performance of production within each product range. Therefore, backyard agricultural profitability is directly proportional to sales and inversely proportional to the economic value of noncommercialized (unused or rotted) products (Equation (1)). The higher the value of BAP KPI, the greater the economic benefit of production.where BAP is backyard agricultural profitability, sales is the economic value of products sales, and noncommercialized refers to the economic value of noncommercialized products (Source: own elaboration).

2.2. Case Study

Object of Study

3. Results

3.1. Supply Chain Analysis

3.2. Improvement Opportunities

3.3. Annual Production Projection

3.4. Improvement Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Urquía-Fernández, N. La seguridad alimentaria en México. Salud Publica de México 2014, 56, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.L.; Damián, M.A.; Álvarez, F.; Parra, F.; Zuluanga, G. The economics of the backyard as a survival strategy in San Nicolás de los Ranchos, Puebla. Revista Geografía Agrícola 2012, 48, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Barrientos, L.; Magaña-Magaña, M.A.; Latournerie-Moreno, L. Economic and social importance of backyard agro-biodiversity in a rural community of Yucatán, México. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2015, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pillo, F.; Anríquez, G.; Jimenez-Bluhm, P.; Galdames, P.; Nieto, V.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Hamilton-West, C. Backyard poultry production in Chile: Animal health management and contribution to food access in an upper middle-income country. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 164, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Sistema Nacional de Información Estadística y Geográfica (SNIEG). Sistema de Cuentas Nacionales de México. Producto Interno Bruto Trimestral. Available online: bit.ly/2MZRdhL (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca, México (SAGARPA-FAO)—Food and Agriculture Organization. Agricultura Familiar con Potencial Productivo en México. Available online: bit.ly/2MfYfze (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Jarquín, N.H.; Castellanos, J.A.; Sangerman-Jarquín, D.M. Pluriactivity and family agriculture: Challenges of rural development in México. Rev. Mexicana Ciencias Agrícolas 2017, 8, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: exploring their role in rural development. Soc. Ruralis 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönhart, M.; Penker, M.; Schmid, E. Sustainable local food production and consumption. Challenges for implementation and research. Outlook Agric. 2009, 38, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, O.A. Analysis of the cranberry production chain in Mexico and Chile. PORTES Rev. Mexicana Estudios sobre Cuenca Pacífico 2018, 1231–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Lambert, G.; Aguilar Lasserre, A.; Azzaro-Pantel, C.; Miranda-Ackerman, M.A.; Purroy-Vázquez, R.; Pérez Salazar, M.R. Behavior patterns related to the agricultural practices in the production of Persian lime (Citrus latifolia tanaka) in the seasonal orchard. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 116, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.; Martínez-Flores, J.L.; Cavazos, J.; Moreno, Y.M. Mezcal supply chain in Zacatecas State: Current situation and perspectives. Contaduría Administración 2014, 59227–59252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Aramyan, L.H. A conceptual framework for supply chain governance. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2009, 1136–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Reardon, T.; Rozelle, S.; Timeer, P.; Wang, H. The emergence of supermarkets with Chinese characteristics: Challenges and opportunities for China’s agricultural development. Dev. Policy Rev. 2004, 22557–22586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, J. Family farmers and major retail chains in the Brazilian organic sector: Assessing new development pathways. A case study in a peri-urban district of Sau Paulo. J. Rural Stud. 2009, 25322–25332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minten, B.; Randrianarison, L.; Swinnen, J. Global retail chains and poor farmers: evidence from Madagascar. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.; Verma, D. Connecting Small-Scale Farmers With Dynamic Markets: A Case Study of a Successful Supply Chain in Uttarakhand, India, Regoverning Markets Innovative Practice Series. Available online: https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/G03250.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Secretaria de Gobierno. Sistema Nacional de Información Municipal (SEGOB); Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal (SNIM). Available online: bit.ly/2MgCv6z (accessed on 29 September 2019).

- Stringer, M.F.; Hall, M.N. A generic model of the integrated food supply chain to aid the investigation of food safety breakdowns. Food Control 2007, 18755–18765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, J.L.; Hoffman, L.C.; Piet, J.J. Essential food safety management points in the supply chain of game meat in South Africa. In Game Meat Hygiene in Focus; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-90-8686-840-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizzanty, T.; Collins, R.J.; Russell, I. Complex Adaptive Processes in Building Supply Chains: Case Studies of Fresh Mangoes in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the ISHS Acta Horticulturae 794: II International Symposium on Improving the Performance of Supply Chains in the Transitional Economies, Hanoi, Vietnam, 31 August 2008; pp. 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.K.; Nielsen, J.; Larsen, E.P.; Clausen, J. The fish industry—Toward supply chain modeling. J. Aquatic Food Prod. Technol. 2010, 19, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; del Pilar Baptista, M. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4562-2396-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, D.; Riveros, H. Commercialization Strategies that Facilitate Market Access for Agricultural Producers; Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA): San José, Costa Rica, 2016; ISBN 978-92-9248-646-4. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. Available online: bit.ly/2KOjuoV (accessed on 20 February 2017).

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL). Medición de la pobreza, Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Indicadores de Pobreza por Municipio. 2015. Available online: Bit.ly/2YOQoPW (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Social México (SEDESOL). Sistema de Apoyo para la Planeación de Zonas Prioritarias. Available online: bit.ly/2ZeS5W4 (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Ayers, J.B.; Odegaard, M.A. Retail Supply Chain Management, 2nd ed; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varughese, G.; Ostrom, E. The contested role of heterogeneity in collective action: Some evidence from Community Forestry in Nepal. World Dev. 2001, 29747–29765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuñiga-Arias, G.; Ruerd, R.; Van Boekel, M. Managing quality heterogeneity in the mango supply chain: Evidence fro Costa. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz (GEV). Sistema de Información Municipal. Veracruz, México. 2016. Available online: bit.ly/3090qIs (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Blackburn, J.; Scudder, G. Supply chain strategies for perishable products: The case of fresh produce. Prod. Oper. Manag. Soc. 2009, 18, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xaba, B.G.; Masuku, M.B. An analysis of the vegetables supply chain in Swaziland. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2013, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, D.; Woodhouse, P.; Young, T.; Burton, M. Constructing a farm level indicator of sustainable agricultural practice. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 39, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Encuesta Nacional Agropecuaria 2017. Available online: bit.ly/304XEDM (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- Feenstra, G. Creating space for sustainable food systems: Lessons from the field. Agric. Human Values 2002, 19, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobe, H.L. Farmers’ markets: Consuming local rural produce. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2001, 25, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco de México (BANXICO). Sistema de Información Económica. 2018. Available online: bit.ly/2THvGMg (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Lundqvist, J.; Fraiture, C.; Molden, D. Saving Water: From Field to Fork Curbing Losses and Wastage in the Food Chain; Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI): Stockholm, Sweeden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). EU Actions Against Food Waste [WWW Document]. Food Waste Measurement. Available online: bit.ly/31HU8Q3 (accessed on 19 June 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO). The importance of enabling inclusive and efficient agricultural food systems. In Strategic Work of Food and Agriculture Organization for Inclusive and Efficient Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food System in the EU. A State of Play of Their Socio-ECONOMIC Characteristics; European Commission Joint Research Centre for Scientific and Policy Reports: Seville, Spain, 2013; ISBN 978-92-79-29288-0. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, D. La Identidad Cultural y el Desarrollo Territorial Rural, una Aproximación desde Colombia; Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural (RIMISP): Santiago, Chille, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duché-García, A.; Bernal-Mendoza, H.; Ocampo-Fletes, I.; Juárez-Ramón, D.; Villarreal-Espino, O.A. Backyard agriculture and agroecology in the strategic food security project (PESA-FAO) of the state of Puebla. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2017, 14, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Villanueva, J.L.; Morales-Jiménez, J.; Domínguez-Torres, V. Economic importance of the backyard and its relation to food security in communities of high marginalization in Puebla, Mexico. Agroproductividad 2017, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao-Qiang, J.; Chong, W.; Fu-Suo, Z. Science and technology backyard: A novel model for technology innovation and agriculture transformation towards sustainable intensification. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1655–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, H.M. La Organización Económica de los Pequeños y Medianos Productores. Presente y Futuro del Campo Mexicano, Serie Documento de Trabajo No. 232. RIMISP; Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Larder, N.; Lyons, K.; Woolcock, G. Enacting food sovereignty: Values and meanings in the act of domestic food production in urban Australia. Local Environ. 2014, 1956–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.; Mwema, C.; Gierend, A.; Nedumaran, S. Sorghum and Millets in Eastern and Southern Africa. Facts, Trends and Outlook; Working Paper Series No. 62 ICRISAT Research Program, Markets, Institution and Policies; International Crops Research Institute for Semi-Arid Tropics: Telangana, India, 2016; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Murugani, V.G.; Pereira, L.M.; Sobratee, N.; Govender, L.; Slotow, R.; Modi, A.T. Mainstreaming underutilized indigenous and traditional crops into food systems: A South African perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.C.; Lamie, D.; Stickel, M. Local foods systems and community economic development. Commun. Dev. 2017, 48612–48638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Average Price 1,3 | Expected Harvest | T 2 | Annualized Value (USD) 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chontla | Tempoal | Chontla | Tempoal | |||

| Plum | 0.99 | 1 | 1.040 | 15.620 | 1025 | 15,401 |

| Nopal | 1.97 | 2 | 2.666 | 0.035 | 10,514 | 138 |

| Creole pumpkin | 0.64 | 2 | 5.796 | 0.414 | 7429 | 531 |

| Coriander | 2.46 | 4 | 0.489 | 0.012 | 4822 | 118 |

| Passion fruit | 1.48 | 1 | 0.600 | 1.380 | 887 | 2041 |

| Jobo | 0.99 | 1 | 0.780 | 1.650 | 769 | 1627 |

| Litchi | 0.99 | 1 | 0.500 | 0.625 | 493 | 616 |

| Tamarind | 1.48 | 1 | 0.240 | 0.388 | 355 | 574 |

| Creole chili | 0.99 | 1 | 0.773 | 0.101 | 762 | 99 |

| Totals | 27,057 | 21,145 | ||||

| Product | Self-Consumption 1 | Sales 1 | Noncommercialized 1,2 | BAP KPI 3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nopal | 3739 | 2303 | 4472 | 51.5 |

| Creole pumpkin | 2522 | 1590 | 3317 | 47.9 |

| Coriander | 1747 | 1027 | 2049 | 50.1 |

| Plum | 346 | 258 | 421 | 61.3 |

| Passion fruit | 305 | 222 | 360 | 61.6 |

| Jobo | 283 | 164 | 322 | 51.0 |

| Creole chili | 272 | 172 | 318 | 54.2 |

| Litchi | 177 | 133 | 182 | 73.0 |

| Tamarind | 117 | 83 | 155 | 53.4 |

| Totals | 9509 | 5953 | 11,596 | 51.3 |

| Product | Self-Consumption 1 | Sales 1 | Noncommercialized 1,2 | BAP KPI 3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plum | 5248 | 2855 | 7298 | 39.1 |

| Passion fruit | 714 | 387 | 940 | 41.2 |

| Jobo | 582 | 427 | 618 | 69.1 |

| Litchi | 246 | 111 | 259 | 42.9 |

| Tamarind | 206 | 127 | 241 | 52.7 |

| Creole pumpkin | 175 | 143 | 212 | 67.6 |

| Coriander | 40 | 21 | 58 | 36.0 |

| Nopal | 41 | 40 | 57 | 70.7 |

| Creole chili | 34 | 21 | 44 | 46.7 |

| Totals | 7286 | 4132 | 9727 | 42.5 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Galván, F.; Bautista-Santos, H.; Martínez-Flores, J.L.; Sánchez-Partida, D.; Ireta-Paredes, A.d.R.; Fernández-Lambert, G. Backyard Agricultural Production as a Strategy for Strengthening Local Economy: The Case of Chontla and Tempoal, Mexico. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195400

Sánchez-Galván F, Bautista-Santos H, Martínez-Flores JL, Sánchez-Partida D, Ireta-Paredes AdR, Fernández-Lambert G. Backyard Agricultural Production as a Strategy for Strengthening Local Economy: The Case of Chontla and Tempoal, Mexico. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195400

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Galván, Fabiola, Horacio Bautista-Santos, José Luis Martínez-Flores, Diana Sánchez-Partida, Arely del Rocio Ireta-Paredes, and Gregorio Fernández-Lambert. 2019. "Backyard Agricultural Production as a Strategy for Strengthening Local Economy: The Case of Chontla and Tempoal, Mexico" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195400

APA StyleSánchez-Galván, F., Bautista-Santos, H., Martínez-Flores, J. L., Sánchez-Partida, D., Ireta-Paredes, A. d. R., & Fernández-Lambert, G. (2019). Backyard Agricultural Production as a Strategy for Strengthening Local Economy: The Case of Chontla and Tempoal, Mexico. Sustainability, 11(19), 5400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195400