Abstract

Green attributes transparency presents new opportunities and challenges to advertisers. This study developed a research framework to enhance consumers’ willingness to adopt green cosmetics from several green constructs, such as corporate transparency, corporate social responsibility (CSR), green brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity, and showed the green field strategy implications. This study commissioned a professional survey company to distribute an online questionnaire of cosmetic using experience to the participants. AMOS statistics software was used to analyze the measurement reliability and validity, and to examine the research hypotheses using structural equation modeling. The contribution of the study aimed to provide a correct standpoint for new concepts of green strategy in accordance with environmental trends, activities, and positive enterprise image to increase the consumers’ willingness to adopt green cosmetics from five constructs.

1. Introduction

Market transparency affects product differentiation. Firms can complete their market transparency by providing the information related to prices and their products through advertising [1]. Transparency products are interpreted as differentiated goods, in comparison with all existing market products. There is transparent value in building brands that are perceived by consumers to be authentic and trusted. Transparency can be viewed as one of the advertising tools in the toolbox.

Green marketing with environmental consciousness is a critical development in the phenomenon of emerging economies. Green marketing has positive impacts on environment, consumers, the general public, and economies [2]. Due to rising environmental consciousness, consumers increasingly choose those green products which are harmless to our environment which drives consumers to consider and purchase the product with the green attributes transparency. Green attributes transparency has become so necessary that it drives contemporary, environment-friendly policy [3,4]. The environment issue has become mainstream in the world. Therefore, the goods and services provided by enterprises should also meet the needs of the mainstream, and environmentally friendly products are one of these conditions [5]. The awareness of environmental subjects is increasing [6] and environmental values tend to improve pro-environmental behavioral intentions [7,8]. Previous studies have explored the positive relationship between consumers’ involvement and willingness of buying environment-oriented products [6,9]. Attitudes toward the brand engaged in green marketing communications directly and positively affect green brand support intentions and green brand purchase intentions [10]. CSR-relevant information disclosure improves a sense of environment-oriented responsibility [11]. Therefore, if consumers have positive attitudes towards environmental subjects, they tend to be willing to pay excess prices to ensure the product quality [6].

Corporate transparency has been discussed within several fields of prior literature. Being a type of a moral issue [11], transparency influences not only environmental behavior but also company–stakeholder relationships [4,12]. The proprietary directors think that those companies which are highly visible will have the opportunity to increase value for their shareholders [13]. There is a direct relationship between industrial manufacturing and environment pollution. Green cosmetics companies have emphasized their concern about environmental conditions and the use of minimal amounts of packaging. However, while previous studies have explored and paid attention to the issues of company strategy to their products [11,14], few of them explored strategies related to green attributes transparency. A few studies discuss corporate green transparency and green management, but they fail to examine green brand equity [4]. Green brand equity can be added to or subtracted from the value provided by a product or service [5]. Companies that implement environmentally friendly initiatives and convey their eco-ideas are able to increase consumer purchasing intention toward green products [15]. An exhaustive search of the archival literature clearly suggests a research gap. We aim to fill this gap and explore the influence on WTA of green attributes transparency variables with CSR and green brand concepts.

This study concerns the level of green attributes transparency and focuses on the sharing of sufficient information and its explanation to allow consumers to evaluate the corporate transparency of the green cosmetic business. The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between green attributes transparency and its outcome. Despite the importance of the subject and its consequences, there is little empirical evidence about the green cosmetics industry. We aim to understand whether green strategy, the one which is used for implementation in the green businesses and engaged in the green activities, will affect consumer willingness to adopt green cosmetics; however, this study is based on six dimensions to develop a research framework and to explore the relationship between each of them. We develop a theoretical framework about green transparency and draw out new implications of the literature on CSR and green branding. We offer a correct standpoint of new concepts about green attributes transparency, which in compliance with environmental trends should increase the role of related constructs, such as CSR image, green brand image, green brand trust, green brand equity and consumer WTA green cosmetics.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Relationship between Green Attributes Transparency and CSR

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) involves the self-regulation of enterprises to compliance with public rules and social norms [16]. The issue has been discussed and developed all over the world [17,18], and is increasingly a topic of concern for both academics and practitioners [19]. If a firm’s credibility is seen as a more socially responsible one, it should devote more social responsibility perceptions of it in public [13] and thus consumers will accept it [20,21].

Inferred from the definition of general transparency, green transparency can be described as a construct implying availability, openness or green information disclosure [22]. Green transparency policy is important for supporting industry level modifications which aim at improving the environment; it is an essential requirement to foster CSR. Information disclosure in this view has a stimulating influence on consumer image of and attitude toward CSR. Green transparencies allow consumers to see through the product’s natural ingredients, add support to protect the environment, and so on; it leads consumers to have a moral conscience which may promote the CSR image [11,23]. Customers would like to understand the detailed information related to their contributions as consumers on the provision of social responsibility initiatives [4]. Transparency can help firms to improve allocative and dynamic efficiency, as well as innovation to engender a superior CSR image compared to others [11]. Consequently, customers will use the available information they receive to evaluate the CSR image toward the firms [4].

In general, it appears that enterprises’ transparency execution of their green performance is a critical factor in their attempt to discriminate their CSR image from other companies without transparency performance [11]. A successful green product innovation depends on proactive CSR [24]. Thus, the enterprise that presents higher green corporate transparency will tend to acquire a greater image of CSR. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

The green attributes transparency is positively associated with CSR.

2.2. Relationship between Green Attributes Transparency and Green Brand Image

When it is hard to find the tangible quality or characteristic to differentiate products or services, brand image itself plays a quite important role in the market [5,25,26]. Brand image is defined as “the perception about a brand as reflected by the brand association evoked in the consumer memory”. With regard to the brand associations, they are the appearances connecting with the brand held in consumers’ memories [27] Thus, the brand image is the brand association with the particular brand’s symbolic attributes [5,28]. It appears in the consumers’ mind when a brand name is simply mentioned [29]; in Keller’s typology there are three symbolic components of a brand image: favorability, strength, and uniqueness of brand association [28]. The brand image has been discussed in terms of three key perspectives—corporate image, social image, and product image [30,31]. Corporate image involves the consumer’s image regarding the corporation that produces the specific good or supplies the specific service. Social image is the way a particular brand is accepted within society as representative of a certain status. Product image refers to the image associated with the product or service [31].

Enterprises with great attitudes toward their brand can create positive associations about their brand and achieve a good brand image [28,29]. In general, an enterprise’s success invariably strongly relies on consumers and prestige relations [32,33]. At the present time, people are paying more and more attention to the issue of environmental protection. If enterprises are going to thrive they cannot ignore the pressure of environmental trend; contrarily, they have to make efforts to cultivate their green brand image. A green enterprise’s brand image and prestige are established by their transparency, information, communication, and procedures [33]. Consumers loyal to them expect more transparency from them in order to respond favorably in the enterprise’s operation [12]; that transparency will improve the brand image when consumers know they comply with formal regulations [12].

The argument being made is that when a green enterprise displays higher green corporate transparency, consumers have a higher regard for the enterprise’s green brand image. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

The green attributes transparency is positively associated with green brand image.

2.3. Relationship between CSR and Green Brand Trust

Trust encompasses three basic viewpoints: integrity, ability, and benevolence [5,34]. For our purposes, trust refers to the customer relying on the company’s integrity, ability, and benevolence which assures it in performing the function this brand states [35,36,37]. Brand trust is a brand with a high degree of customers’ confidence resulting from belief in its integrity and trustworthiness [37,38]. Furthermore, brand trust implies that the brand embodies and instills positive and credible beliefs; it can be defined as “the willingness of the average consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function” [36,39]. That is, green brand trust is ‘‘a willingness to depend on a product, service, or brand, based on the belief or expectation resulting from its credibility, benevolence, and ability about its environmental performance.’’ This idea has been very fruitful and is widely used in current research.

Green brand trust can be instilled by CSR. Corporations can utilize a CSR strategy to reinforce their brand trust and reputation by demonstrating their ethical obligations and commitment to the various stakeholders [40]. In addition to bringing the enterprise’s merits to the foreground, CSR also influences the customers’ response. CSR can effectively generate positive attitudes toward the company, reducing consumer suspicion about the enterprise, and in turn achieving establishment of green brand trust [21]. Numerous studies claim that there is positive link between CSR, environmental performance, and competitive advantages. Therefore, the CSR concept of building enterprise competitive advantage (brand image) will help attribute green brand trust to the enterprise [41].

We have argued that when an enterprise presents an impression of higher CSR it will attract consumers oriented towards an enterprise’s higher green brand trust. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

The CSR is positively associated with green brand trust.

2.4. Relationship between CSR and Green Brand Equity

Brand equity is an intangible brand asset and an implicit internal value in a celebrated brand name [5,42]. Aaker defines brand equity as “a set of brand assets linked to a brand’s name or symbol that added to the value provided by a product or service” [43]. Keller proposes a customer-based notional brand equity concept, defined as “differential effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to the marketing of the brand” [29]. Brand equity to the enterprise is also often bifurcated into two perspectives, seen and understood from either a financial-based [5,44] or a consumer-based perspective [29,43]. Brand equity is the representative property and invisible characteristic of the brand in the marketing domain [45,46], conveying value [43] and communicating the brand knowledge to the customer [47]. Customer-based brand equity appears when a consumer is familiar with a brand and associates the brand with the virtue of being favorable, strong, and unique [48]. This latter idea is adopted in this research.

CSR is an excellent tool for firms to enhance their legitimacy among consumers [49]. Using CSR as a discriminating element distinguishes themselves as a successful green company within their industries [50,51]; for example, an emphasis upon discrimination becomes a way to achieve competitive advantages [41]. This pattern is evidenced in previous studies of companies devoted to providing green products. It was found that they engage in green marketing, which may be associated with their CSR image and in turn promotes their equity [40,51].

We have argued that when an enterprise presents a higher CSR impression, the consumers’ perception on enterprise green brand equity is enhanced higher. This leads to proposing the following hypothesis:

H4.

CSR is positively associated with green brand equity.

2.5. Relationship between Green Brand Image, Green Brand Trust, and Green Brand Equity

In general, the attitudes of consumers are affected by the brand images of companies. When that brand image is distinctly positive it can alter consumer attitudes toward the brands/products [8]. A company with brand image representing high consumer product quality perceptions [52,53] bestows a number of advantages on a firm.

Brand trust is the quality of the brand helping to meet the satisfaction of prevention targets [54]. Outstanding brands are distinguished by success, confidence, leadership, expertise, and efficiency. The vast strength of their brand image of such good brands typically involves strong brand associations with high levels of credibility and trust [55]. Trust has been widely regarded as an important brand element; heritage brands especially concern about and try hard to maintain trust because they have more to lose [56]. Because the brand image may simultaneously reduce consumers’ risk perception and improve the feasibility of purchase, brand image and consumer trust have a positive relation [5].

Brand equity is customer-based and is constructed of brand image and brand knowledge [29]. Keller proposes that corporate brand equity results from the amount of action of the corporation and its brand [57]. Corporate brand image is referred to an operation of the organization and the way in which it communicates. Furthermore, an organization’s operations and communications are involved in affecting brand image, and in turn enhance brand equity [47]. Thus, an enterprise’s brand image establishes and affects its brand equity. Prior studies have shown that when consumers have a positive association to a brand, this brand will acquire strong brand equity and demand a premium price [58]. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to argue that a more positive brand image can help develop brand equity [59]. There is a positive relation between green brand image and green brand equity. The relation is partially mediated by green satisfaction and green trust [60].

Our claim is that when an enterprise is perceived to have a higher green brand image, it will promote itself to consumers regarding the enterprise’s higher green brand trust and brand equity. Thus, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5.

The green brand image is positively associated with green brand trust.

H6.

The green brand image is positively associated with green brand equity.

2.6. Relationship between Green Brand Trust and WTA

Consumers tend to develop a singular positive belief (and attitude) about the recycling of products and purchase green products to express their sense of social responsibility [6,61]. The WTA research related to green products documents generally how consumers would like to protect the environment and display a willingness to adopt environmentally friendly products [62]. The objectives of WTA research concern the moral implication that people care about—whether the products they consume are the output of a producing process which is sustainable and responsible. Often, the requirements are green products, fair trade, products not made by child labor, and those from companies with CSR [63]. Those consumers that participate more in protecting environment events tend to adopt green products more [6,9]. The crucial point of green product WTA is being willing to pay more to adopt the green product to replace and substitute the current product [64].

The concept of brand trust means that consumers have positive and credible beliefs in one brand, and on the basis of that trust will decide to make their purchase. Brand trust can lead to the customers’ brand commitment and loyalty, creating a close relationship between the customer and the corporation [37,38]. Brands with trust are frequently purchased, have a high degree of identity, and enjoy comparatively more market share and premium prices [36,37]. Moreover, brand trust often results in positive behavioral outcomes. Customers will shift the parent brand trust to other product purchases when they believe in this brand and consider it risk free [65]. Thus, brand trust can generally affect a customer’s purchase decision-making regarding the brand or product [24]. This indicates that brand trust reflects the intention of trust and plays a critical role in the transaction process [66]. If the capacity, reliability and credibility exist to meet customers’ special interests and brand trust, then the customers will commit to the brand because of psychological stratification [39].

Prior studies of the green product phenomenon have suggested participants express the view that they possibly choose a brand in the main because it is attached to a manufacturer committed to an environmental harm reduction process [8]. Based on this, it can be inferred that when consumers purchase green cosmetics, they will normally depend on the green brand trust to make their adoption decision.

We have argued that when the enterprise presents an impression of higher green brand trust, it will promote consumers’ higher willingness to adopt enterprise’s green products. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H7.

The green brand trust is positively associated with WTA.

2.7. Relationship between Green Brand Equity and WTA

The chief marketing research topics focus on brand equity generalization, units of measurement, management to perform the brand market outcome, and helping the company’s decision making [65]. Speaking of a company’s success or failure, brand equity is the critical factor of a brand’s success, [67] since strong brands can help obtain competitive advantages [29,48,57]. Keller points out that brand equity is the added value attached to a product [29]; it can create brand knowledge to affect a differential customer brand marketing response [5]. Keller also relates the customer-based brand equity model to product-market outcomes [29], suggesting that higher brand equity may generate better price flexibility and more positive brand performance [48]. A company having higher brand equity can gain higher consumer’s brand perception and brand loyalty, less competitive vulnerability and negative response regarding price increases, higher middlemen’s support, greater profit margins and marketing promotion effects, and increases in its opportunities [28].

It has been widely accepted in prior research that purchase intentions are normally based on brand equity [59]. There is evidence to support those who claim consumer-based brand equity is generated by the judgment of a brand’s value to consumers which drives their subsequent purchase behaviors [67]. Therefore, higher brand equity will be advantageous for an enterprise, yielding the consumer’s willingness to pay more for the product when they are attracted by the brand name for its quality level [24]. Ottman [68] illustrated how the passive green consumer is willing to pay more to consume a pro-environmental product while he or she is exposed to the effective marketing emphasizing environmental brand value [8]. Analyses show significant positive effects of green brand equity on both brand attitude and positive word-of-mouth communication [60].

We have argued that when the enterprise presents an impression of higher green brand equity, it will promote the consumers’ higher willingness to adopt enterprise’s green products. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H8.

The green brand equity is positively associated with WTA.

2.8. Mediating Effect of CSR Image, Green Brand Image, Green Brand Trust, and Green Brand Equity

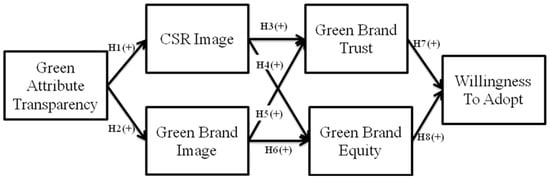

As stated above, we expect that the link between green attribute transparency and green outcome of willing to adopt is mediated by CSR image, green brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity. We expect that green attribute transparency is positively related to CSR image, green brand image, in turn to green brand trust, green brand equity, finally to green brand equity (see Figure 1). Thus, the following hypothesis is expected:

H9.

CSR image, green brand image, green brand trust, green brand equity will mediate the relationship between green attribute transparency and WTA.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model. Note: CSR: Corporate Social Responsibility

The relationships implied by the research framework are summarized in Figure 1.

3. Research Methods

This research develops a framework for testing the hypotheses outlined above. According to ENS [61], chemicals used in cosmetics have been found to be harmful to human health (e.g., isoprene and epichlorohydrin are known as human carcinogens) and to poison the environment (e.g., siloxanes D4 and D5). It is well known that many consumers who want to avoid these dangers will tend to use cosmetics with natural materials and prefer the one produced in a transparent manufacturing process. Consequently, in this research project we consider it reasonable to select and to zoom-in on green cosmetics companies as representative of the larger and wider growing green industry movement. The questions raised in this research are about how the influence of green cosmetics company green attributes transparency engages on CSR and the customers’ green brand image perception, green brand trust, and green brand equity. How do these further realize the consumers’ WTA of the friendly environmental protection products of a green cosmetics company? The respondents had to have cosmetics use experience, opt for one green cosmetics brand, and then fill in the questionnaire with the chosen brand bearing in mind. We applied structural equation models (SEM) to evaluate the hypotheses.

3.1. Measures

Our methodology is straightforward; that is, using reliable construct items adapted from prior literature to modify and form the original scale measurements. The measurement of green corporate transparency is modified from the work of Vaccaro and Echeverri [4], comprising four items. Five items captured from Alcañiz et al. [14] are used to scale measured CSR. Green brand image, trust, and equity constructs are all measured through a modified version [5] with four, five, and three items respectively. The modified scales from Jansson et al. [64] measure WTA for green cosmetics, including four items. The measurements of the questionnaire are measured using a conventional 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

Before conducting our investigation in Taiwan we were considerably concerned about the fundamental cross-cultural validation of the questionnaire we wanted to use. It was therefore translated from English to Chinese, and then translated back into English and compared with the original to ensure the equivalence. For pretest, in order to make sure of the reliability and local arrangement of the questions, 21 graduate students in related departments of cosmetics participated. While revising the questionnaire, we took 21 graduate students’ suggestions and opinions into consideration so as to improve and strengthen the accuracy and completeness of the questionnaire, culminating in a pretest confirmation and further revision. Shortly afterwards, a professional online survey company with large scale representation in Taiwan presented and collected the formal questionnaires. They invited consumers who had experience with cosmetics to respond to the questionnaire; 868 interviews were collected, of which 145 were rejected as invalid, which left 723 as usable data for the final analysis. The response rate was 83.3%.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Accuracy Analysis

The criteria for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) are assessed to evaluate the fitness of the model structure in this study context. The criteria related to CFA good fit are as follows: Chi-square/df lower than 5, Comparative Fit Index higher than 0.9, Incremental fit index higher than 0.9, Normed fit index higher than 0.90, Tucker-Lewis index higher than 0.9, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation lower than 0.08, and Standardized root mean square residual lower than 0.1 [69]. As demonstrated below, all goodness-of-fit values are acceptable. The CFA model has an overall Chi-square/df of 3.62, a CFI of 0.96, an IFI of 0.96, a NFI of 0.95, a TLI of 0.96, a RMSEA of 0.06, and an SRMR of 0.029. Therefore, the model structure achieves a reasonable fit.

Individual reliability and construct reliability are used to test scale reliability. Individual reliability is based on composite reliabilities (CR) and factor loadings. Composite reliability (CR) values should exceed 0.6 [69]; all factor loadings higher than 0.5 are significant [70]. The CR values (ranging from 0.89 to 0.95) are all significantly above 0.6; all the factor loadings as well are above 0.5 and significant (ranging from 0.74 to 0.93), indicating that the individual reliability indicators are within acceptable ranges. Construct reliability is examined with Cronbach’s α, which should exceed the minimum threshold of 0.7. Each Cronbach’s α exceeds 0.7 as shown in Table 1, meeting the suggested benchmark for acceptable construct reliability.

Table 1.

Measurement properties.

Convergent validity is tested by examining the factor loading of each item (t-values exceeding 1.96) and the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct exceeding 0.5 [70]. As shown in Table 1, the AVE scores of every construct ranged from 0.68 to 0.80, and the factor loadings of the items are significant, satisfying the convergent validity requirement. AVE is also adopted to examine discriminative validity. The AVE for each construct must be higher than the squared correlations between the construct and other constructs in the model [70]. Table 2 shows the AVE for each construct is higher than the respective squared correlations between the construct and other constructs in the model, demonstrating evidence for discriminant validity among the constructs.

Table 2.

Average variance extracted (AVE) and square correlations between research constructs.

The AVE values are underlined and positioned on the diagonal. Factor square correlations are below the diagonal.

4.2. Structural Model Results

This study uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to verify the research hypotheses’ results. The ratio of Chi-square/df, CFI, IFI, NFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR values clearly fit the related criterion values recommended in the literature (5.10, 0.94, 0.94, 0.93, 0.93, 0.075, and 0.09), providing evidence of an adequate model fit. As hypothesized, green corporate transparency exerts significant positive effects on CSR image (γ = 0.695, p-value < 0.001) and green brand image (γ = 0.708, p-value < 0.001), in support of H1 and H2. Furthermore, CSR image exerts significant influences on green brand trust (β = 0.289, p-value < 0.001) and green brand equity (β = 0.297, p-value < 0.001), in support of H3 and H4. Green brand image is also found to have a significant positive effect on green brand trust (β = 0.649, p-value < 0.001) and green brand equity (β = 0.500, p-value < 0.001). Thus, Hypotheses 5 and 6 are supported. For the consequent result, the brand trust and green brand equity influences on willingness to adopt (WTA) are as predicted positive, with standardized path coefficients of 0.316 (p-value < 0.001) and 0.365 (p-value < 0.001), respectively. Thus, H7 and H8 are supported. The squared multiple correlations (R2) are 0.482 for CSR, 0.501 for green brand image, 0.688 for green brand trust, 0.485 for green brand equity, and 0.324 for WTA. Table 3 also shows an examination of the proposed hypotheses.

Table 3.

The results of the structural equation model.

4.3. Mediating Effect

For testing the 9th hypothesis of mediation effects, we used bootstrapping procedures [71] to estimate the indirect effects of CSR, green brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity.

According to SEM statistical software analysis, the estimated coefficient of direct effect from green corporate transparency to corporate social responsibility is 0.16 (t-value = 2.23). The estimated coefficient of direct effect from green corporate transparency to green brand image is 0.18 (t-value = 2.84). The estimated coefficient of direct effect from corporate social responsibility and green brand image to green brand trust are 0.25 (t-value = 4.43) and 0.66 (t-value = 12.96). The estimated coefficient of direct effect from corporate social responsibility and green brand image to green brand equity are 0.18 (t-value = 2.51) and 0.57 (t-value = 8.20). The estimated coefficient of direct effect from green brand trust and green brand equity to willingness to adopt are 0.35 (t-value = 6.16) and 0.36 (t-value = 5.77).

Indirect effect is divided into three parts. First, the estimated coefficient of indirect effect from green corporate transparency to green brand trust is 0.16 (t-value = 2.84). Second, the estimated coefficient of indirect effect from green corporate transparency to green brand equity is 0.13 (t-value = 2.85). Third, the estimated coefficient of indirect effect from green corporate transparency, corporate social responsibility, and green brand image to willingness to adopt are 0.10 (t-value = 2.78), 0.15 (t-value = 3.75), and 0.44 (t-value = 9.87). Green corporate transparency has indirect effects on willingness to adopt by these four mediating variables: corporate social responsibility, green brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity. Green corporate transparency positively influences CSR and green brand image, and CSR and green brand image positively influence green brand trust and green brand equity, which in turn are positively related to WTA. Thus, green corporate transparency has a significant indirect effect on willingness to adopt. CSR, green brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity serve as the mediating variables in this construction between the three antecedent factors and WTA (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The coefficient and t-value of the direct and indirect effect.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

The production activities of enterprises often have a negative impact on the earth, harming the environment and causing climate change. The question of how to protect and maintain the earth’s fragile balance and of how to diminish environmental harm are urgent topics and critical tasks for enterprises. Given this growing concern, more and more companies have started to engage in green product development. Designing, manufacturing, and promoting green products is rapidly turning into a new industrial trend. Simultaneously, more and more consumers are paying attention to the issue of environmental protection. Corporations know their consumers well, and green attributes transparency has become an increasingly important green marketing strategy. This study explores and discusses the consequence of green attributes transparency on CSR image, brand issues and willingness to adopt green product provides.

The research findings demonstrate that enterprise performance green transparency has a significantly positive influence on CSR image [24] and brand image [13]. Proof of green attributes transparency will encourage consumers to believe corporate CSR performance and develop brand image. The result also shows that consumer perception toward CSR image and brand image of cosmetic companies positively influence green brand trust [42] and green brand equity [41,52], and the latter two constructs in turn affect the WTA for green cosmetics. This significant pattern expresses the fact that the cosmetics company has higher green brand trust, as well as establishing good brand equity, both of which will induce the potential consumer to favor this enterprise and be willing to purchase their products [9,61].

5.2. Theoretical Implication

This study investigates how implementing an enterprise green strategy and brand concepts affect customer willingness to adopt and clarifies the effect of green corporate transparency of antecedent variable. Further, this research reveals four intermediary variables: CSR, green brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity, which typify the subtle relationship between three antecedent factors and WTA of green cosmetics products. Previous researchers have discussed enterprise CSR and brand image regarding enterprise brand trust and equity influence, and their influence on willingness to adopt products in the general industry [5,14]. Although there has been prior research on enterprise transparency and the WTA of products [4] as well as green brand management [5], it is sparse and scattered. This study has been primarily concerned with joining the green concept together with the CSR variable and integrates related green brand concept variables into the conceptual framework, pointing towards the essential parameters of a complete theoretical model.

We have confirmed and proven the notion that green transparent information marked as a natural ingredient will stimulate consumers with moral consciousness, promoting their intention to purchase green products [12,23]. In addition, this research approach models the mediating effect of CSR and green brand concepts within a structured research framework, one which typifies the subtle relationship between green attributes transparency and WTP. Based on the rising trend of green environmental consciousness, this study combines the green concept with brand, environmental protection, and corporate social responsibility related variables in the conceptual framework of green brand trust and green brand equity, providing new theoretical opinions.

5.3. Managerial Implication

It is possible for enterprise marketers to read off some practical implications from our research findings. First, inasmuch as green attributes transparency is a key success factor of green strategy, media coverage can help companies clear their green information so as to achieve and promote their CSR and brand image. Second, with reference to CSR, it is advantageous for green cosmetics companies to provide customers with information about how their brand functions with society’s interests in mind. Companies should integrate philanthropic contributions into their business activities, consumers should learn about their environmental protection policy and socially responsible ways, thereby achieving and promoting their green brand trust and green brand equity. Third, with reference to the green brand image issue, green companies may strengthen the consumer belief in their brand claim, diligently projecting their brand as trustworthy on environmental promises and professional environmental reputation. Fourth, since the green brand trust performance is frequently relied upon, the question of whether the green cosmetic brand’s environmental concern meets consumer expectations appears. Doing so will make consumers feel their promises and commitments for environmental protection. Consequently, green enterprise managers should emphatically publicize the related information, so consumers may trust their enterprise experience and green production profession. Fifth, when the brand equity is well established on environmental concern and its environmental promises, it is regarded as the best benchmark of environmental commitments. When the brand integrates philanthropic contributions into its business activities, these strategies will cause the consumer to have a forward-looking impression of this enterprise and will more likely engage in purchase behavior. Sixth, corporate social responsibility and green brand image may have an indirect effect on the willingness to adopt two mediating variables: green brand trust and green brand equity. Thus, enterprise managers should clearly emphasize their environmental protection concept, performance, profession, and social welfare activities to achieve customer WTA via their good brand trust and brand equity accomplishment. Finally, as a result, green attributes transparency has an indirect effect on willingness to adopt the mediating variables: CSR image, brand image, green brand trust, and green brand equity. Hence, it should be noted by marketers whether a significantly large number of customers are willing to spend a premium to adopt environmentally friendly products [6,72] and thereby promote their green concepts.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

The framework of the research project reported above has several limitations that should be considered in the future while planning further investigations. First, this study asks the respondents to opt for one green cosmetics brand and then complete a questionnaire. There are many other data collection methods such as having informants involve themselves in in-game advertising (IGA) or advergames and then filling in a questionnaire. Second, this research places exclusive emphasis upon the cosmetics industry in Taiwan. The essential themes and variables discussed should be explored comparatively in studies of different industries in different countries. Finally, our study is aware of but does not take other variables into account, such as advertising, environmental material usage, and green expertise, all of which play an important role in green strategy [4,15]. Their causal role should be fully examined in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-L.C.; Data curation, Y.-H.L.; Formal analysis, Y.-H.L. and S.-L.C.; Investigation, S.-L.C.; Methodology, Y.-H.L. and S.-L.C.; Software, Y.-H.L.; Supervision, Y.-H.L.; Writing—original draft, S.-L.C.; Writing—review & editing, Y.-H.L.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Hsiang Ling Huang.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schultz, C. Market transparency and product differentiation. Econ. Lett. 2004, 83, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singhal, A.; Singhal, P. Exploratory research on green marketing in India. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 12, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, A.M.; Reed, D. Partnerships for Development: Four Models of Business Involvement. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Echeverri, D.P. Corporate Transparency and Green Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoussi, L.H.; Linton, J.D. New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, R.; Pickett-Baker, J.; Pickett-Baker, J. Pro-environmental products: Marketing influence on consumer purchase decision. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhwerk, M.E.; Lefkoff-Hagius, R. Green or Non-Green? Does Type of Appeal Matter When Advertising a Green Product? J. Advert. 1995, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.; Tiamiyu, M.F. GREEN consumption values and Indian consumers’ response to marketing communications. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbink, W.; Graafland, J.; Van Liedekerke, L. CSR, Transparency and the Role of Intermediate Organisations. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kistruck, G. Seeing Is (Not) Believing: Managing the Impressions of the Firm’s Commitment to the Natural Environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Sepulveda, C. Does media pressure moderate CSR disclosures by external directors? Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 1014–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, E.B.; Cáceres, R.C.; Currás, R.P. Alliances between Brands and Social Causes: The Influence of Company Credibility on Social Responsibility Image. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudal, T. An Attempt to Determine the CSR Potential of the International Clothing Business. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Juslin, H. The Impact of Chinese Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: The Harmony Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, I.; Hasnaoui, A. The Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Vision of Four Nations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; Van Rossem, A.A.; Buelens, M.M. Small-Business Owner-Managers’ Perceptions of Business Ethics and CSR-Related Concepts. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 425–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. Charitable programs and the retailer: Do they mix? J. Retail. 2000, 76, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsch, J.; Gupta, S.; Grau, S.L. A Framework for Understanding Corporate Social Responsibility Programs as a Continuum: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanski, M.E.; Kahai, S.S.; Yammarino, F.J. Team virtues and performance. An examination of transparency, behavioral integrity and trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Burke, P.; DeVinney, T.; Louviere, J.J. What Will Consumers Pay for Social Product Features? J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 42, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. Proactive and reactive corporate social responsibility: Antecedent and consequence. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, S.M.; Doyle, P.; Wong, V. An exploration of branding in industrial markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1997, 26, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Measuring Brand Equity Across Products and Markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, D.; Allen, D. Communicating Experiences: A Narrative Approach to Creating Service Brand Image. J. Advert. 1997, 26, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, F.M.; Altuna, O.K. The effect of brand extensions on product brand image. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, A.L. How brand image drives brand equity. J. Advert. Res. 1992, 32, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, J.J.; Heiser, R.S.; Williams, J.D.; Taute, H.A. Consumer racial profiling in retail environments: A longitudinal analysis of the impact on brand image. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 18, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Ethical branding and corporate reputation. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2005, 10, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Lozano, J.M.; Arenas, D. Exploring the nature of the relationship between CSR and competitiveness. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurr, P.H.; Ozanne, J.L. Influences on Exchange Processes: Buyers’ Preconceptions of a Seller’s Trustworthiness and Bargaining Toughness. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 11, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain effects from brand trust and brand effects to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparelia, N.; White, L.; Hughes, K. Drivers of brand trust in internet retailing. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, S.T.K.; Yip, L.S.C. The moderator effect of monetary sales promotion on the relationship between brand trust and purchase behavior. J. Brand Manag. 2008, 15, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, M.; Papasolomou, I.; Vrontis, D. Cause-related marketing: Building the corporate image while supporting worthwhile causes. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.B.; Boehe, D.M. How do Leading Retail MNCs Leverage CSR Globally? Insights from Brazil. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, O.; Yasin, N.M.; Noor, M.N. Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2007, 16, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, C.J.; Sullivan, M.W. The Measurement and Determinants of Brand Equity: A Financial Approach. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassar, W.; Mittal, B.; Sharma, A. Measuring customer-based brand equity. J. Consum. Mark. 1995, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Cultivating service brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, M.; Juntunen, J.; Juga, J. Corporate brand equity and loyalty in B2B markets: A study among logistics service purchasers. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, Y.; Yu, C. Global brand equity model: Combining customer-based with product-market outcome approaches. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, R.; Ash, J.; Hope, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Audit: From Theory to Practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 62, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Socially Responsible Organizational Buying: Environmental Concern as a Noneconomic Guying Criterion. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.P.; Ainscough, T.; Shank, T.; Manullang, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Socially Responsible Investing: A Global Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaman, R.; Arasli, H. Customer based brand equity: Evidence from the hotel industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2007, 17, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzouk, N.; Wells, D.M.; Seitz, V. The importance of brand equity on purchasing consumer durables: An analysis of home air-conditioning systems. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Love, E.; Staton, M.; Chapman, C.N.; Okada, E.M. Regulatory focus as a determinant of brand value. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.-A.A.; Sung, Y. The roles of spokes-avatars’ personalities on brand communication in 3D virtual environments. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urde, M.; Greyser, S.A.; Balmer, J.M.T. Brands with a heritage. J. Brand Manag. 2007, 15, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. The brand report card. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Kamenidou, I. Perceptions of potential postgraduate Greek business students towards UK universities, brand and brand reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holehonnur, A.; Raymond, M.A.; Hopkins, C.D.; Fine, A.C. Examining the customer equity framework from a consumer perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 17, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekk, M.; Sporrle, M.; Hedjasie, R.; Kerschreiter, R. Greening the competitive advantage: Antecedents and consequences of green brand equity. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 1727–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L.J.; Lowrey, T.M.; Mccarty, J.A. Recycling as a marketing problem: A framework for strategy development. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENS, Canada Declares Chemicals Used in Cosmetics to Be Toxics. Available online: https://www.chemicalonline.com/doc/canada-declares-chemicals-used-in-cosmetics-0001 (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Jansen, P.; Gössling, T.; Bullens, T. Towards Shared Social Responsibility: A Study of Consumers’ Willingness to Donate Micro-Insurances when Taking Out Their Own Insurance. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Green consumer behavior: Determinants of curtailment and eco-innovation adoption. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Aaker, D.A. The Effects of Sequential Introduction of Brand Extensions. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munuera-Alemán, J.L.; Delgado-Ballester, E.; Yagüe-Guillen, M.J. Development and Validation of a Brand Trust Scale. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broyles, S.A.; Leingpibul, T.; Ross, R.H.; Foster, B.M. Brand equity’s antecedent/consequence relationships in cross-cultural settings. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J. Green Marketing: Opportunity for Innovation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcker, D.F.; Fornell, C. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).