Abstract

Climate change related events affect informal settlements, or slums, disproportionally more than other areas in a city or country. This article investigates the role of slums in the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for the Paris Agreement of a selected group of 28 highly urbanized developing countries. Content analysis and descriptive statistics were used to analyze first the general content in these NDCs and second the proposed role, or lack thereof, of slums in these documents. The results show that for most of the analyzed countries, context-based climate policies for slums are not part of the strategies presented in the NDCs. We argue that a lack of policies involving informal settlements might limit the capacity of developing countries to contribute to the main goals of the Paris Agreement, as these settlements are significant portions of their urban populations. One of the hopeful prospects of the NDCs is that they will be reviewed in 2020 for the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26). With this paper, we aim to stimulate discussions about the crucial role that informal settlements should play in the NDCs of developing countries in the background of the synergies required between climate change actions and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Climate change related events make no distinction between developed and developing countries. Nevertheless, it has been documented that the developing world is less prepared to face climate change challenges and therefore is more vulnerable [1,2,3]. This is particularly true for one group: the informal settlements of the developing world or the slums. In these areas climate change risks are higher, the adaptive capacity is lower, exclusion from policies is more evident, and responses in the case of emergencies are almost nonexistent [4,5]. In this article, we use the terms slums and informal settlements interchangeably.

Different from climate change, the slums have been considered important urban issues for a long time. These settlements were part of the history of industrialized nations, as they dealt with urbanization and inequality [6,7]. Today, however, urban informality is a major territorial phenomenon mostly affecting the developing world. According to the World Bank [8], around 30% of the urban population in developing countries lives in slums. The proportion of urban population living in informal settlements is highest in Sub-Saharan Africa (55.2%), followed by South Asia (30.5%), East Asia and Pacific (25.8%), and Latin America and the Caribbean (20.5%) [8]. In total, around one billion people, or around 13% of the global population, live in slums, and this number is expected to increase in the following years [4,9], thus, these settlements are significant populations to be studied in climate change policies.

Informal settlements are highly vulnerable to climate change for several reasons. Various studies highlight how these communities are established in low lying coastal areas, on flood-prone riverbanks, on unstable hillsides, and in other hazard-prone areas, have poorly designed infrastructures to resist climate events, and have minimal attention from local or central governments that often ignore them, hide them, or try to make them invisible [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The combination of these factors makes these communities highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

To prevent the acceleration of global warming (mitigation) and help communities be more resilient to its effects (adaptation), various international agreements have been adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the most recent one of which was adopted on the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21); the Paris Agreement. This agreement, which replaces the Kyoto Protocol (COP3), will guide the climate change related policies of most countries for the foreseeable future. The main goal of the Paris Agreement is to limit the increase of global temperatures to 2 °C and aim for a 1.5 °C increase by the end of the century [20]. The agreement also encourages countries to increase their adaptation potential. Each country submitted its own contribution plans for the agreement, initially called intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs). The idea was that the sum of all INDCs will result in achieving the main goals of the agreement, however as it stands, even with a 100% success rate from all presented INDCs, the resulting temperature increase will be 2.7 °C [21], suggesting the need for further action. Another reason that could limit the ability of the agreement to reach its goals is that the United States (U.S.) formally withdrew from the agreement, alleging that it was unfair to the country (this becomes official in November 2020, as stated in article 28 of the Agreement). This is significant because the U.S. is responsible for about 14% of all yearly global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [22]. It is noteworthy that the INDCs became nationally determined contributions (NDCs), not “intended” anymore, once countries joined or ratified the agreement and adopted it as part of their national frameworks and policies. As of August 2019, 179 parties have joined or ratified the agreement, including all but two of the countries analyzed in this article (Liberia and Turkey).

The literature on the Paris Agreement is nascent and still emerging. Some of the literature has focused on analyzing the document [23,24,25,26,27], quantifying the emissions reductions and the accumulative results from the NDCs [28,29,30], or investigating potential strategies and methodologies to track the NDC progress in specific regions of the world [31,32,33,34]. The focus on operational research has resulted in several understudied topics, or gaps, such as the impact of this climate change treaty on specific groups, such as informal settlements.

Against this background, this article asks: what is the role, if any, of informal settlements or slums in the adaptation and mitigation strategies proposed in the NDCs of highly urbanized developing countries? Furthermore, the article tries to uncover whether or not including these communities as part of proposed climate policies in the NDCs is related to indicators such as the country’s income, proposed emissions reductions pledges, or climate change vulnerability.

Studying proposed climate actions for informal settlements is significant because as large areas of developing countries, these territories play an important role in the planning of policies to create sustainable and resilient cities [35]. These areas are also part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically goal 11 “Sustainable Cities and Communities”, with concrete targets such as, “by 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums” [36]. Policies to increase the adaptive capacity or to reduce carbon emissions in these territories can have important effects on the contributions of developing countries to fight climate change, as globally one in eight people live in slums, and these communities sometimes represent the majority of a country’s urban population.

2. Climate Change in Slums, and the Nationally Determined Contributions

Urbanization in Africa, Latin America, and most of Asia continues to be distinguished by urban informality, resulting in what Davis [37] called a “planet of slums”. The most authoritative definition of the term “slum” was adopted by the United Nations and defines them as communities lacking one or more of the following: (1) access to improved water, (2) access to improved sanitation facilities, (3) sufficient living area, (4) structural quality/durability of dwellings, and (5) security of tenure [4]. These communities have cropped up without conforming to local land use regulations and often without being listed in government records, official maps, or titling registries [37,38]. Even though conditions in these places are deplorable and not adequate to support living, “squatters trade physical safety and public health for a few square meters of land and some security against evasion” [37] (p. 121). The slums offer the only affordable housing to migrants and to poor populations of expanding developing cities [39].

According to the literature on urban informality and climate change, these territories are the most vulnerable to climate change-related events because they: (a) are the most exposed to shocks and stresses such as climate variability and extremes, (b) are the most sensitive to these shocks and stresses, and (c) have the least capacity to respond [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Furthermore, their geographic location exacerbates their vulnerabilities. Tropical areas are where most developing countries reside, covering the major parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Of the 28 countries analyzed in this paper, 20 are located in the tropics. In this line, recent studies indicate that climate change will disrupt natural systems in tropical regions significantly more than in other regions, putting more pressure on socioeconomic coping mechanisms there [10,14,15,16,48,49]. These studies suggest that while extratropical regions might experience higher warming, these regions experience high yearly climate variability, unlike the tropics, where small climate variability can have devastating effects on the natural systems that support social and economic development. In other words, vulnerability to climate change in developing countries is not only the result of financial and technological constraints, as is often posed in the literature [49,50,51], but also based on physical geographic location [10].

These findings from the literature help explain why many developing countries, especially small island developing states, pushed for the 1.5 °C target to be adopted as the main goal of the Paris Agreement. A study by King and Harrington [16] found that “exceeding the 1.5 °C global warming target would lead to the poorest experiencing the greatest local climate changes” (p. 5030). This paints a picture in which climate change mitigation and adaptation mechanisms globally can have a profound effect on the wellbeing and sustainable development of developing countries in the tropical regions, and in particular, of informal settlements [51,52,53].

In this line, the submitted NDCs of developing countries for the Paris Agreement are different in content, but not in structure, from the ones proposed by developed countries. An important feature of these NDCs is that most developing countries based their contributions on the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities [51], meaning that they believe that the developed world should take the lead in climate change mitigation. In this line, many developing countries stated that their contributions for the agreement are conditional on international support and technology transfer. However, certain developing countries (mostly middle-income countries) proposed significant non-conditioned contributions.

Nevertheless, the NDCs from developing countries are pivotal to achieve the goals of the agreement. Scholars believe that without significant emission reduction from developing countries, emissions will keep rising and the world will keep warming [54,55]. The agreement itself in states Article 9 that developed country parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country parties with respect to both mitigation and adaptation in continuation of their existing obligations under the Convention. The importance of developing countries’ and emerging economies’ mitigation contributions for the agreement is now augmented after the decision of the U.S. to leave the agreement. Historically, developed countries were most responsible for climate change, but nowadays, in terms of aggregated carbon emissions (not per capita), developing countries are also prominent emitters, representing 63% of all total yearly emissions [56,57]. Additionally, trends suggest that the developed world is reducing emissions quickly; however, emissions from the developing world are rising and expected to rise during the period covered by the Paris Agreement [58].

In regards to adaptation strategies, these are key components in the NDCs of developing countries and are critical to combat climate change, especially in informal urban poor settlements [1,3,59]. While the main goal of an NDC is to show the mitigation pledges a country proposes to limit emissions of greenhouse gases, the UNFCCC encouraged countries to include adaptation sections in their NDCs. Article 7 of The Agreement states that parties should establish goals in adaptation as a way of “enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerabilities to climate change”. The Agreement also states that adaptation should be undertaken, taking into consideration vulnerable groups and ecosystems.

The NDCs can present a coherent argument on the benefits of programs that increase the adaptive capacity of informal settlements, enhance mitigation, alleviate poverty, and decrease inequality. This is in line with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on 1.5 °C that urges countries, especially developing ones, to integrate mitigation and adaption pledges with sustainable development as part of multifaceted bidirectional policies [52,60,61]. This integration would require multilevel and cross-sectoral strategies, linking a mix of mitigation and adaptation strategies needed to accelerate the systemic transitions of cities in the global south [52].

The first review process or stocktake to quantify countries’ contributions towards the agreement will take place in 2023 and various meetings will precede it, including the submission of new NDCs in 2020. By uncovering the role of informal settlements in the initial mitigation and adaptation strategies from the NDCs of a group of highly urbanized developing countries, this article aims to stimulate discussions on the benefits and importance of including these communities in developing countries’ climate policies in the foreground of the upcoming NDCs review mechanisms.

3. Methodology

3.1. Highly Urbanized Developing Countries (HUDC)

In this study, we analyze the NDCs of developing countries, which are mostly urban. Investigating highly urbanized developing countries and their climate change policies is significant because as the world continues to urbanize, sustainable development challenges will be increasingly concentrated in cities, particularly in the lower–middle-income countries, where the pace of urbanization is fastest [62]. Consequently, grouping countries with similar socio-economic realities has been promoted as a good research mechanism to understand climate policies derived from NDCs [30].

Countries that are mostly rural might concentrate their NDC strategies in these groups, as some rural communities are groups for special consideration under the Paris Agreement (Article 7). While rural groups are also vulnerable to climate change, the conditions of informality in the city are more specific and concentrated in cities. The selected list of countries does not aim to be exhaustive, but does provide a good overview of urban informality in highly urbanized countries of the developing world. The selected countries are different in size, population, and culture; they are located in the three continents (Africa, Asia, and Latin America) where the phenomena of urban informality is more pressing.

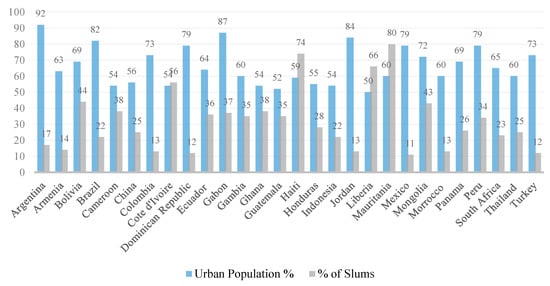

A total of 72 developing countries were initially identified using data from the World Bank that have over 50% of their population living in urban areas. Out of these countries, 36 have data on the percentage of their urban population living in slums, and these were selected for further analysis. The list was reduced to a final 28 countries because eight countries submitted their initial NDCs in a language other than English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, or Chinese (languages that the authors could understand), or because a country did not submit an INDC for the COP21. Countries excluded from the initial list of 36 were Angola, Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, and Syria. Figure 1 shows the final list of countries selected for this study and their respective urban population (in terms of a percentage of total population) and slum population (in terms of a percentage of urban population).

Figure 1.

Selected 28 countries’ urban population (percentage of total) and slum population (percentage of urban population).

3.2. Data Sources

Countries’ classification data—urban population (percentage of total), slum population (percentage of urban population), GDP (current US dollar), and GDP per capita (current US dollar)—were retrieved from the World Bank databases. The analyzed NDCs were taken from the official submitted documents to the UNFCCC COP21 and are available online [63]. Additional data on the selected countries’ vulnerability to climate change were obtained from the Global Climate Risk Index Model proposed by Kreft, Eckstein, and Melchior [64].

3.3. Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research methodology used to interpret meaning from the content of text data and, hence, adheres to the naturalistic paradigm [65]. It makes it possible to make replicable and valid inferences by interpreting textual material, and uncover specific intentions and relationships [66,67]. Content analysis of specific categories from official climate documents is a useful research tool to identify specific climate change related actions in a comparative way [68] and this method has been applied in other studies analyzing NDCs [69,70]. As the original INDCs are textual documents submitted under international law to the UNFCCC, this methodology was suitable for extracting, classifying, and grouping text data from these documents in this study [67].

The analysis was based on a close examination of the original INDCs submitted to the COP21 of 28 HUDC. As mentioned above, these documents became NDCs once countries joined the agreement. Even if two of the analyzed countries have not joined the Paris Agreement yet, for the purposes of this paper, we will refer to these aggregated documents as NDCs. Classified and extracted data categories of interest to this article were: emissions reduction pledges, sectors of implementation, strategies to implement (adaptation and mitigation), conditions (if any), and proposed role of informal settlements. While the precise language of the NDCs helped in coding these categories in an objective way, the authors of this paper that acted as coders meticulously read all 28 NDCs multiple times to avoid missing important data. The precise language of the NDCs enabled consistent code allocation and assured that this process can be easily replicated.

The last step of the analysis involved interpreting the results of the content analysis and uncovering patterns and relationships. For this, correlation analysis was performed to find whether some of the abovementioned variables (including countries’ classification data, e.g., GDP per capita, and NDC data, e.g., pledges) were related. Correlation coefficients, denoted by R, between the variables were computed to measure how strong the relationship was between them (i.e., how closely data in a scatterplot fell along a straight line). The range of R was between −1 and 1; if R is equal to 1 or −1, then the data set is perfectly aligned, whereas data sets with values of R close to 0 show little to no straight line relationship. R can be calculated according to Equation (1):

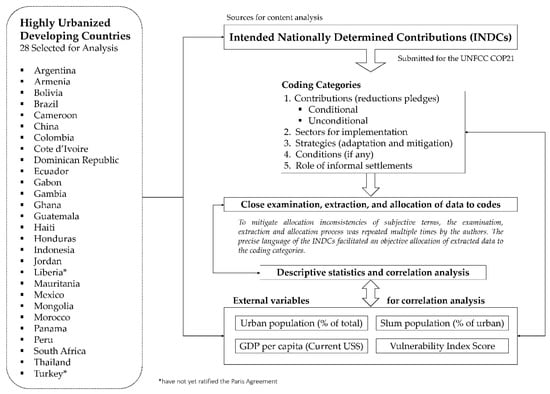

where xi and yi represent two of the analyzed variables for country i, respectively, is the arithmetic mean of , and is the arithmetic mean of . xi and yi. Figure 2 shows a formal process of the content analysis used in this research.

Figure 2.

Content analysis methodology flowchart.

4. Results and Discussion

The results of the content analysis are described below. We present first the general findings from the NDC analysis in regards to differences in reduction pledges (Section 4.1) and whether these proposed contributions depend on countries’ income or vulnerability to climate change (Section 4.2). Then, we comment on the results from the analysis about the role, or lack thereof, of informal settlements in the NDCs, and the policies proposed by the countries with specific strategies involving these communities (Section 4.3). Finally, in Section 4.4, first we plead for the importance of explicitly including strategies for informal settlements in the NDCs by highlighting possible benefits locally and for the Paris Agreement, and second, we combine the findings from the previous sections to describe variance between countries in regards to the analyzed country’s indicators and including, or not, informal settlements.

4.1. Conditional and Unconditional Commitments

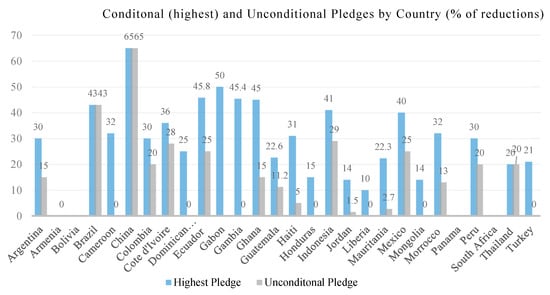

The analysis and coding of the NDCs of highly urbanized developing countries with high prevalence of slums revealed the differences in the commitments for the Paris Agreement among these countries. The conditional pledges represent the maximum amount of GHGs a country could reduce in the upcoming years (in comparison to a baseline scenario, which varies from 2000 to 2013 depending on the country), and it includes reductions dependent on whether the country receives support from the international community. Under the highest pledge, China had the largest commitment (65% reduction, 2005 baseline); however, this reduction is expressed as a reduction of emissions per unit of GDP (intensity type NDC) and not as absolute reductions of GHGs (fixed or baseline scenario type NDC). The highest absolute conditional reduction in GHGs came from Gambia (45.4% reduction, 2010 baseline), and the lowest from Liberia (10%). Unconditional pledges, on the other hand, are the commitments by countries not conditioned on external support. Of the HUDC analyzed, Brazil (43% reduction, 2005 baseline) and Indonesia (29%, 2010 baseline) had the highest unconditional commitments. This is particularly encouraging because these countries are ranked seventh and ninth, respectively, in yearly global GHG emissions by country [22], and as developing countries (non-Annex I), they did not have legal commitments under the Kyoto Protocol. Some countries, such as Armenia, Bolivia, and Panama, did not explicitly express conditional or unconditional reduction pledges; instead, they presented general strategies to fight climate change. Figure 3 shows the rest of the conditional and unconditional pledges proposed by the 28 HUDC in their NDCs.

Figure 3.

Conditional and Unconditional Pledges for the COP21.

Figure 3 also exposes how many of the analyzed countries (12 out of 28) did not propose unconditional pledges in their NDCs (Armenia, Bolivia, Cameroon, Dominican Republic, Gabon, Gambia, Honduras, Liberia, Mongolia, Panama, South Africa, and Turkey). This supports the idea that many developing countries are still reluctant to commit to reducing GHG emissions, because these reductions can limit economic prosperity. One of the so-called “victories” of the Paris Agreement was eliminating Annex I and non-Annex I subdivisions and getting contributions from all countries. However, most of the contributions by developing countries are subject to conditions, as the analysis revealed, and at the same time, they are not sufficient to achieve the agreement [20,21]. In a way, the wounds of Annex I and non-Annex I countries from the Kyoto Protocol are still present in the Paris Agreement. This suggests that the UNFCCC must identify novel ways to involve developing countries in unconditional reduction programs in order for the emergent climate regime to be successful [51,52,53].

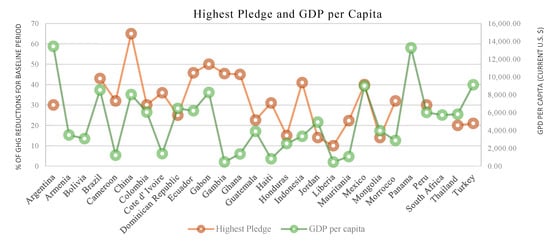

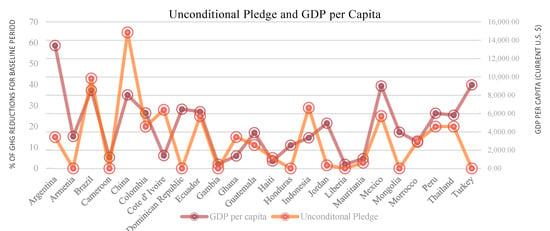

4.2. Relationship of GDP Per Capita and Climate Change Vulnerability to the Pledges

While the different baseline scenarios and target types hinder the possibility of making direct comparisons between proposed pledges, the variance among the selected countries in regards to conditional and unconditional commitments is significant. For instance, the commitments are not related to the country’s income level. The results of the analysis show that the correlation between the highest pledge of reduction and GDP per capita is modest (correlation coefficient R = 0.22) (Figure 4). A stronger, yet moderate, correlation was found between unconditional pledge and GDP per capita (R = 0.412) (Figure 5); thus, the income level among the selected group of developing countries is not necessarily related to the amount a country unconditionally or conditionally commits to reducing their emissions. The 12 countries that did not describe explicit unconditional reduction pledges were not the least developed ones in the group, in fact, they represented every income level.

Figure 4.

Highest pledges and GDP per capita.

Figure 5.

Unconditional pledges and GDP per capita.

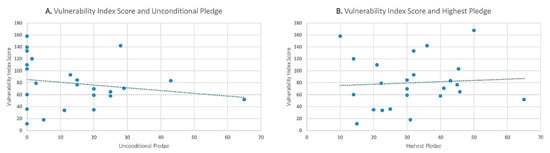

Furthermore, the analysis shows that there is a weak correlation between unconditional pledges and the countries’ vulnerability index score (VIS) (R = 0.19), and between highest pledge and VIS (R = 0.06) (Figure 6). The vulnerability index is a score developed by Germanwatch [64] that measures the overall vulnerability of a country to climate change: the lower the score a country receives the higher its vulnerability. The results of this analysis imply that for the selected countries there seems to be more important or pressing issues than reducing emissions, even if these countries are considered some of the most vulnerable to climate change events. This finding goes in line with the recent My World survey by the United Nations, which found that for lower income and low-development countries, climate change actions are not a priority. The survey asked participants to rank the most pressing issues in their countries. The issues presented ranged from education, health, income, and others, and out of these, climate change action was placed last out of 16 places of important priorities [71].

Figure 6.

Climate vulnerability and nationally determined contributions (NDC) pledges among the selected countries. (A) Unconditional pledges, (B) highest pledges.

4.3. Informal Settlements in the NDCs

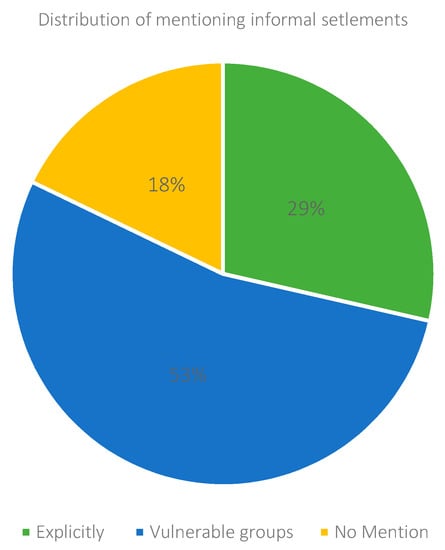

To answer the main question of this article, while reviewing the NDCs, special attention was paid to finding, highlighting, extracting, and coding strategies or goals, mentioning keywords or phrases representing informal settlements. These keywords could be: informal, marginalized, urban poor, unplanned, unregistered (areas, communities, zones, or settlements), slums, urban informality, barrios, comunas, favelas, campamentos, shantytowns, shack, or any other concept that infers the United Nations’ definition of informal settlements [4]; this represented an explicit or implicit use of the term. Only eight out of the 28 analyzed countries mentioned specific strategies involving communities living in urban informality. Additionally, 15 of them mentioned strategies for “vulnerable” groups, but these cannot be counted as strategies specifically for slums because in many cases “vulnerable” in an NDC refers to other groups, such as indigenous communities, women, children, people with disabilities, or others. Five countries did not mention, explicitly or implicitly, any strategies aimed at informal settlements or vulnerable groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution percentage of countries mentioning informal settlements.

As seen in Figure 7, less than a third of the analyzed countries included specific mitigation or adaptation strategies considering informal settlements in their NDCs. Failing to include these areas in the proposed climate policies and strategies continues to marginalize these communities and leaves them outside the defensive targets and urban policies to face climate change events. In addition, without having specific outcome-oriented goals involving slums in the NDCs, developing countries are missing the opportunity to highlight the needs of these settlements in order to allocate international support.

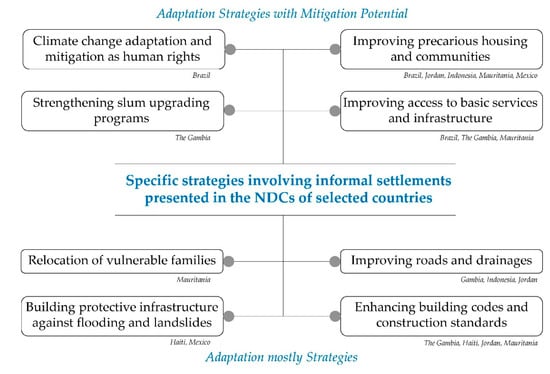

The analyzed countries that mentioned specific policies or strategies involving informal settlements in climate change adaptation and/or mitigation could serve as references for those that did not. For instance, Gambia’s NDC specifically stated that inadequate slum upgrading programs hinder the possibility of achieving resilient and adaptable communities, thus calling for improvements in these programs. Five of the eight countries with specific plans for slums (Brazil, Jordan, Indonesia, Mauritania, and Mexico) mentioned the improvement of precarious housing in informal settlements as a key strategy. Three (Brazil, Gambia, and Mauritania) mentioned plans to improve access to basic services and infrastructure. All eight mentioned increasing the adaptive capacity of slums with different plans. These plans ranged from relocation of vulnerable families (Mauritania), to building protective infrastructure against flooding and landslides (Mexico and Haiti), to improving roads, drainage systems, and other vital infrastructure (Gambia, Indonesia, Jordan), to enhancing the quality of life of slum dwellers (Honduras), and linking climate change adaptation and mitigation as human rights (Brazil). Gambia, Haiti, Jordan, and Mauritania also explicitly stated the importance of urban planning to strengthen adaptation capacity in informal settlements, and explicitly noted that one of the local policies they will take is to enhance building codes and construction standards to be in line with a sustainable development framework. The policies and strategies presented by these countries all align with the Paris Agreement goal of enhancing adaptive capacity, some have mitigation potential, but all are connected with the Sustainable Development Goals, as they are interlinked with the countries’ developing realities and future development aspirations. Figure 8 summarizes these strategies.

Figure 8.

Strategies (mostly adaptation) from countries that incorporated informal settlements in their NDCs.

4.4. The Importance of Specifically Mentioning Informal Settlements

The language of the NDCs is complex and the relationships between different concepts and variables should not be taken as causal, but they are nevertheless suggestive [58]. The results described in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 create a picture where the proposed pledges, income level, and vulnerability to climate change among the selected developing countries are not correlated. In other words, those with higher income or considered “more vulnerable” do not necessarily have higher pledges. Furthermore, when combined with the findings in Section 4.3, the indicators from Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 are not determining factors in including specific climate policies for informal settlements. These findings are aggregated visually in the next two figures.

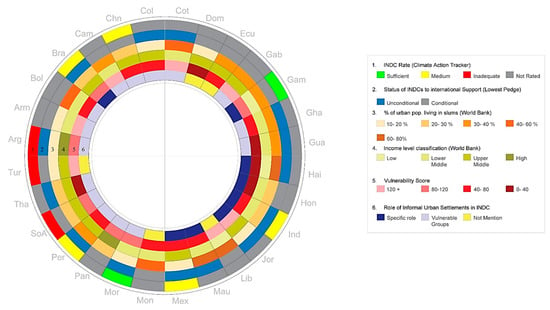

Figure 9 shows the above findings in more detail, exposing the differences in the 28 countries analyzed. The figure maps the individual variables of each country in six criteria: (1) original INDC rate, an evaluation of a country’s proposed pledge aligning with its historical responsibility and capacity and determined by Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent scientific body that carefully analyzes how an INDC aligns with the goals of the agreement; (2) the status of the NDC lowest pledge (conditional or unconditional); (3) the percentage of urban population living in slums; (4) income level classification; (5) vulnerability index score; and (6) mentioning informal settlements in the NDC. The figure helps visualize that there are no identifiable relationships between these variables in these countries, therefore indicating that the commitments of developing countries cannot be generalized.

Figure 9.

NDCs of the 28 countries case studies. Comparative analysis of rate by Climate Action Tracker (CAT), pledge, slums percentage, income level, vulnerability, and role of informal settlements in contribution. Note: countries’ names are abbreviated in the outer part of the circle.

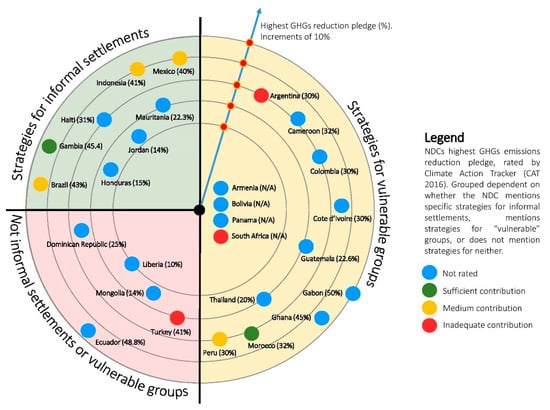

Furthermore, Figure 10 displays each analyzed country’s maximum reduction pledge (regardless of whether it is conditional) in a quadrant that is dependent on whether the NDC mentions informal settlements, mentions vulnerable groups, or does not mention either vulnerable groups or slums. The figure also assigns a color code to show the rate given to a particular NDC by CAT. While most of the analyzed NDCs were not rated, those rated were not related to mentioning slums.

Figure 10.

NDCs of case studies based on maximum pledge, rate, and role of informal settlements.

The specific language of an NDC is crucial; the use of specific, concrete, and concise language is important in legal documents, and especially in international law [27,72,73,74]. At the same time, it is recommended to use outcome-based goals linked to the objectives of the agreement in the NDCs in order to receive funds from international cooperation [60]. Not mentioning slum communities is a lost opportunity for developing countries to make the needs of informal settlements in relation to adaptation and mitigation visible to the international community, to allocate funds and investment.

Additionally, informal urban settlements, as part of subnational structures, can be key contributors to the commitments of developing countries towards the agreement for both adaptation and mitigation. The Paris Agreement solidified the participation of subnational governments, such as cities and municipalities, in global mitigation and adaptation efforts, continuing the shift towards a polycentric landscape of climate action [75]. The success of this emergent regime would depend, at least partially, on its ability to integrate climate action from non-state and subnational entities (ibid). While the slums might not be legally under the perimeters of defined sub-national entities, they are large territories (in some developing countries up to 80% of the urban population) physically integrated into cities, and as such, they will affect mitigation and adaptation efforts in most developing countries [68].

In this line, there is a consensus in the literature that cities will be crucial for the success of the Paris Agreement in limiting the increase in global temperatures [29,30,35,76]. As the combined NDCs presented for the Paris Agreement result in a median warming of 2.6–3.1 degrees Celsius by 2100, the contribution of cities going beyond national pledges is even more crucial [3]. Many local organizations, including cities, have already joined transnational climate initiatives that go beyond national pledges; these efforts can result in higher transparency as cities render themselves accountable for their obligations.

One possible answer to the lack of specific strategies for informal settlements in most NDCs is that they are not considered a heterogeneous group on the urban landscape, but just as part of the larger concepts, such as “urban” or “city”. However, slums are often not part of legal jurisdictions of urban areas or regions and are often not part of urban registries and maps, therefore living in a geographic and administrative exclusion limbo.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

In the background of the required synergies between climate change actions emerging from the Paris Agreement and sustainable urban development, this article analyzed the NDCs of 28 highly urbanized developing countries to scrutinize the climate strategies presented in these documents, namely those towards informal settlements or slums. The results show that most of the analyzed NDCs do not have specific policies for informal settlements. We argue that this absence contributes to the policy exclusion practices towards these settlements and is a missed opportunity to tackle multiple crucial problems in these communities. Without significant contributions from informal settlements, which in some cases represent the majority of the urban population in a developing country, the ability of the new climate change regime to be effective in the developing world can be jeopardized.

Nevertheless, all nationally determined contributions are expected to be enhanced in order to meet the 1.5 °C or 2.0 °C targets of the Paris Agreement [53]. In this line, Höhne et al. [76] stated that, “the next step for the global response to climate change is not only implementation, but also strengthening, of the Paris Agreement”. For the COP26 in 2020, countries will have the opportunity to present new NDCs, leading to the first formal review in 2023. Identifying areas in which countries can enhance their mitigation and adaptation pledges in a framework that is concerned with equity, efficiency, and competitiveness is a crucial task for developing countries. Some of these strategies should happen in slums; in these areas, climate policy mechanisms can link mitigation portfolios with adaptation and sustainable development priorities. Policies for informal settlements should be discussed and included as part of the revised NDCs to guarantee a framework that enhances the adaptive capacity of the most vulnerable and supports sustainable development. In order to address this, we propose the following.

First, the slums should be considered heterogeneous vulnerable groups due to their specific characteristics and complex social structures. Considering informal settlements as an individual group for the Paris Agreement—just as indigenous groups, local communities, and migrants are (Page 2)—can inspire positive transformations by dissecting these territories and proposing policies specifically designed for them. At the same time, states, regions, and cities should delineate their administrative boundaries in order to determine the jurisdiction of slums. Adjudicating slums to particular subnational entities can provide them with better chances for basic services and connectivity to larger climate policy mechanisms. Making slums visible is an important step to extend future climate policies to these communities.

In this line, a multinational organization of developing countries, similar to that of the Covenant of Mayors (COM) [77], could be a mechanism to promote multilevel governance among cities with informal settlements. A model like the COM can encourage new governance models that are inclusive and cooperative, and will allow the sharing of success stories in regards to bi-directional policies that strengthen climate change adaptation and mitigation whilst promoting sustainable development in informal settlements. It will also help in promoting horizontal relationships among this group of cities and countries. While most climate transnational networks are currently in developed countries, the importance of developing countries for the success of the Paris Agreement invites consideration of the implementation of similar models in the global south.

Second, the UNFCCC must seek novel ways to collaborate with developing countries to encourage these countries to propose significant unconditional GHGs reduction pledges while also focusing on other development priorities. The role of internal factors, such as pressing socioeconomic issues in informal settlements, should be part of the climate discussions, but the need for unconditional reduction pledges should be acknowledged, especially among middle-income countries, as these countries still operate under the wounds of the Kyoto protocol.

In this line, the IPCC special report on 1.5 °C states that current marginalized groups such as informal settlements have traditionally not benefited from synergies linking climate policies to development, and therefore the report urges for transformative policy mechanisms that respond to the most vulnerable [63]. Inclusive urban planning and slum upgrading which enhance climate change adaptation and mitigation are some of the strategies that can propel these transformations to move towards a 1.5 °C pathway. Informal settlements are key territorial sectors in which this transition can occur in developing countries. Without significant contributions from developing countries, especially from highly urbanized developing countries, it is difficult to envision the Paris Agreement reaching its main goals. Inside developing countries, the climate policies implemented for slums, which in some cases represent the majority of the population, are critical for the success of the agreement, and thus should be part of the policy frameworks of developing countries’ future NDCs revisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.R.N.C. Methodology: J.R.N.C., H.-H.W., T.-Y.T. Investigation: J.R.N.C. Formal analysis: J.R.N.C. Writing—original draft: J.R.N.C. Writing—review and editing: H.-H.W.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adger, W.N.; Huq, S.; Brown, K.; Conway, D.; Hulme, M. Adaptation to climate change in the developing world. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2003, 3, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L. Climate Change, Disaster Risk and the Urban Poor: Cities Building Resilience for a Changing World; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Climate Change 2014–Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Regional Aspects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis, K.; Benni, J.; Eichwede, K.; Zebenbergen, K. Slum upgrading; Assessing the importance of location and plea for a spatial approach. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.M. Government and slum housing: Some general considerations. Law Contemp. Probl. 1967, 32, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mayne, A.J.C. The Imagined Slum: Newspaper Representation in Three Cities, 1870–1914; Leicester University Press: Leicester, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Population Living in Slums, (% of Urban Population). Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?locations=XO (accessed on 14 March 2017).

- UN-Habitat. Slum Almanac 2015–2016: Tracking Improvement in the Lives of Slum Dweller; Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlstein, I.; Knutti, R.; Solomon, S.; Portmann, R.W. Early onset of significant local warming in low latitude countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 034009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Coalition for Inclusive Housing and Sustainable Communities (IHC Global). Adapting to Climate Change; Cities and the Urban Poor. Available online: https://ihcglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Climate-Change-and-the-Urban-Poor.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2017).

- Brakarz, J.; Jaitman, L. Evaluation of Slum Upgrading Programs: Literature Review and Methodological Approaches; IDB-Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher-Gollach, C. Planning, the urban poor and climate change in small island developing states (SIDS). Unmitigated disaster or inclusive adaptation? Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2015, 37, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.E.; Fischer, E.M.; King, E.D.; Karoly, D.J.; Hawkins, E.; Lewis, S.C.; Dittus, A.J.; Donat, M.G.; Alexander, L.V. The timing of anthropogenic emergence in simulated climate extremes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 094015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, E.; Fischer, E.M.; Harrington, L.J.; Jones, C.D.; Frame, D.J.; Joshi, M. Poorest countries experience earlier anthropogenic emergence of daily temperature extremes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 055007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.D.; Harrington, L.J. The inequality of climate change from 1.5 to 2 °C of global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 5030–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Associated Press. Philippines Erects Wall to Obscure View of Slums. Available online: http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-philippines-erects-wall-to-obscure-view-of-slums-2012may02-story.html (accessed on 14 November 2016).

- Hossain, Z. Pro-poor Urban Adaptation to Climate Change in Bangladesh: A Study of Urban Extreme Poverty, Vulnerability and Asset Adaptation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beukes, A. Making the Invisible Visible. Generating Data on ‘Slums’ at Local, City and Global Scales; Working paper; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK; Available online: https://pubs.iied.org/10757IIED/ (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Climate Action Tracker (CAT). INDCs Lower Projected Warming to 2.7 °C. Available online: http://climateactiontracker.org/assets/publications/CAT_global_temperature_update_October_2015.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2016).

- World Resources Institute (WRI). Historical Emissions. Available online: https://goo.gl/GbHr76 (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Young, R.O. The Paris agreement: Destined to succeed or doomed to fail? Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clémençon, R. The two sides of the Paris climate agreement. Dismal failure or historic breakthrough? J. Environ. Dev. 2016, 25, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamani, L. Ambition and differentiation in the 2015 Paris agreement: Interpretative possibilities and underlying politics. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2016, 65, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaresi, A. The Paris agreement: A new beginning? J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2016, 34, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodansky, D. The legal character of the Paris agreement. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2016, 25, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Emissions Gap Report 2015; United Nations Environnent Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rogelj, J.; Den Elzen, M.; Höhne, N.; Fransen, T.; Fekete, H.; Winkler, H.; Schaeffer, R.; Sha, F.; Riahi, K.; Meinshausen, M. Paris agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2C. Nature 2016, 534, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldy, J.E.; Pizer, W.; Tavoni, M.; Reis, L.A.; Akimoto, K.; Blanford, G.; Carraro, C.; Clarke, L.E.; Edmonds, J.; Richels, R.; et al. Economic tools to promote transparency and comparability in the Paris agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Elzen, M.; Admiraal, A.; Roelfsema, M.; van Soest, H.; Hof, A.F.; Forsell, N. Contribution of the G20 economies to the global impact of the Paris agreement climate proposals. Clim. Chang. 2016, 137, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovaitė, L.; Butkus, M. The European Union possibilities to achieve targets of Europe 2020 and Paris agreement climate policy. Renew. Energy 2017, 106, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, H.L.; Reis, L.A.; Drouet, L.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Den Elzen, M.G.; Tavoni, M.; Akimoto, K.; Riahi, K.; Luderer, G.; Kitous, A.; et al. Low-emission pathways in 11 major economies: Comparison of cost-optimal pathways and Paris climate proposals. Clim. Chang. 2017, 142, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.P.; Andrew, R.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Fuss, S.; Jackson, R.B.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Le Quéré, C.; Nakicenovic, N. Key indicators to track current progress and future ambition of the Paris agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kona, A.; Bertoldi, P.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Rivas, S.; Dallemand, J.F. Covenant of mayors signatories leading the way towards 1.5 degree global warming pathway. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://goo.gl/eSV1U4 (accessed on 12 January 2017).

- Davis, M. Planet of Slums; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault, C. Ahead of Olympics, Brazilian Map Neglected Favelas to Boost Business. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-olympics-rio-landrights-idUSKCN1070G8 (accessed on 14 February 2017).

- Birch, E.L.; Chattaraj, S.; Wachter, S.M. Slums. How Informal Real Estate Markets Work; The University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, J.T. Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group I to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, R.T.; Zinyowera, M.C.; Moss, R.H. The Regional Impacts of Climate Change: An Assessment of Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, H.; Johnson, C.; Allen, A. Built-in resilience: Learning from grassroots coping strategies for climate variability. Environ. Urban. 2010, 22, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.M.; Weeks, J.R.; Engstrom, R. Do the most vulnerable people live in the worst slums? A spatial analysis of Accra, Ghana. Ann. GIS 2013, 17, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C. The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Dev. 1998, 26, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopin, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, V. Urbanization in developing countries. World Bank Res. Obs. 2002, 17, 89–112. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1093/wbro/17.1.89 (accessed on 5 June 2018). [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, P. The Paris agreement 1.5 °C goal: What it does mean for energy efficiency. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1–13 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Albala-Bertrand, J.M. Political Economy of Large Natural Disasters: With Special Reference to Developing Countries; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Hertel, T.W. Climate volatility deepens poverty vulnerability in developing countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 034004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiou du Pont, Y.; Meinshausen, M. Warming assessment of the bottom-up Paris Agreement emissions pledges. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coninck, A.R.; Babiker, M.; Bertoldi, P.; Buckeridge, M.; Cartwright, A.; Dong, W.; Ford, J.; Fuss, S.; Hourcade, J.C.; Ley, D.; et al. Strengthening and implementing the global response. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change; Masson Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, in press; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2018/11/SR15_Chapter4_Low_Res.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Holz, C.; Kartha, S.; Athanasiou, T. Fairly sharing 1.5: National fair shares of a 1.5 °C-compliant global mitigation effort. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2018, 18, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.T. Will the Paris Agreement Provide Positive or Negative Outcomes for Developing Countries; Working paper; National University of Singapore Faculty of Law: Singapore, 2016; Available online: https://law.nus.edu.sg/apcel/cca/Will_Paris_Agreement_produce_good_or_bad_consequences(Final).pdf (accessed on 24 April 2017).

- The Paris Agreement and the Major Emerging Economies. Available online: https://goo.gl/C594mA (accessed on 24 April 2017).

- Developing Countries are Responsible for 63 Percent of Current Carbon Emissions. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/media/developing-countries-are-responsible-63-percent-current-carbon-emissions (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Frumhoff, P.C.; Heede, R.; Oreskes, N. The climate responsibilities of industrial carbon producers. Clim. Chang. 2015, 132, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, P.; Kona, A.; Rivas, S.; Dallemand, J.F. Towards a global comprehensive and transparent framework for cities and local governments enabling an effective contribution to the Paris climate agreement. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 30, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D.; Huq, S.; Pelling, M.; Reid, H.; Lankao, P. Adapting to Climate Change in Urban Areas: The Possibilities and Constraints in Low-and Middle-Income Nations; Iied: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, K.; Rich, D.; Bonduki, Y.; Comstock, M.; Tirpak, D.; Mcgray, H.; Noble, I.A.; Mogelgaard, K.; Waskow, D. Designing and Preparing Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs); World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, J.; Tschakert, P.; Waisman, H.; Abdul Halim, S.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Dasgupta, P.; Hayward, B.; Kanninen, M.; Liverman, D.; Okereke, C.; et al. Sustainable development, poverty eradication and reducing inequalities. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change; Masson Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, in press; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_Chapter5_Low_Res.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision; United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. INDCs as Communicated by Parties. Available online: http://www4.unfccc.int/Submissions/INDC/Submission%20Pages/submissions.aspx (accessed on 12 April 2016).

- Kreft, S.; Eckstein, D. Global Climate Risk Index 2014. Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2012 and 1993 to 2012. Available online: https://germanwatch.org/sites/germanwatch.org/files/publication/8551.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2016).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Katich, K.N. Urban Climate Resilience. A Global Assessment of City Adaptation Plans. Master’s Thesis, MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm, T.; Lindroos, T.J. An Analysis of Countries’ Climate Change Mitigation Contributions towards the Paris Agreement. White Paper. Available online: https://www.vtt.fi/inf/pdf/technology/2015/T239.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Analysis of Indented Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). Available online: https://www.transparencypartnership.net/sites/default/files/analysis_of_intended_nationally_determined_contributions_indcs.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- My World Analytics. Available online: http://data.myworld2015.org/ (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- Obergassel, W.; Arens, C.; Hermwille, L.; Kreibich, N.; Mersmann, F.; Ott, H.E.; Wang-Helmreich, H. Phoenix from the ashes—An analysis of the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Environ. Law Manag. 2016, 28, 3–12. Available online: https://epub.wupperinst.org/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/6374/file/6374_Obergassel.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- Robbins, A. How to understand the results of the climate change summit: Conference of parties 21 (COP21) Paris 2015. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J. Paris COP 21: Power that speaks the truth? Globalizations 2016, 13, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Weinfurter, A.J.; Kaiyang, X. Aligning sub-national climate actions for the new post-Paris climate regime. Clim. Chang. 2017, 142, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhne, N.; Kuramochi, T.; Warnecke, C.; Röser, F.; Fekete, H.; Hagemann, M.; Day, T.; Day, T.; Tewari, R.; Kurdziel, M.; et al. The Paris agreement: Resolving the inconsistency between global goals and national contributions. Climate Policy 2017, 17, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melica, G.; Bertoldi, P.; Kona, A.; Iancu, A.; Rivas, S.; Zancanella, P. Multilevel governance of sustainable energy policies: The role of regions and provinces to support the participation of small local authorities in the covenant of mayors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).