4.2.1. The Results of In-Depth Interviews in NGOs

In the case of our study from the perspective of NGOs, first, the research procedure assumed in-depth interviews. The following answers from the NGOs perspective were obtained. From the perspective of NGOs, effectiveness is perceived differently than by other institutions, and also by social welfare centers. For nonprofit organizations leaving homelessness and having a home may not indicate higher effectiveness, for example, if the homeless became depressed due to loneliness and died from alcohol abuse. One NGO manager stated that “social welfare center employees must trust the NGO employees because every homeless person is different and sometimes for that person is not the best what the clerk might think. Many people after leaving a shelter dies lonely, informing frequently by phone that they do not want to be a home alone. There are critical situations, when employees of other institutions or city police officers are not able to grasp the situation of a person living on a street, and so they should trust NGOs since without this, providing effective assistance, is not possible. As part of the daily work conducted with people living in shelters, the NGO employees see the people a few hours per day for a year and so their knowledge about the life of the homeless is much greater than that of the employee of social welfare center who sees the homeless person mostly during a registration interview and for a short time in the later stages of care. In this situation, trust in the NGO by the social welfare center is even more necessary”. It is interesting that trust is also needed between NGO and the homeless person, because without it the homeless will not agree to the assistance being provided to them. This is rather difficult as homeless generally do not trust institutions.

According to the NGO manager, the definition of effective assistance may be drastically different from that of social welfare center employees. From the perspective of nonprofit organizations, effectiveness is a “change which occurred within the homeless”. An initial success can be that homeless “will go to the doctor and wash up”, as success requires “a long-term relationship and empathy from NGO employees and achieving successive small steps by the homeless.” Such managers can be treated as transformational leaders, who due to their high ethical standards and extensive knowledge, can built relational trust with other network stakeholders and obtain outcomes based on common values. On the other hand, a social welfare center clerk perceives effectiveness as a number of persons leaving homelessness, although they may not be able to lead an independent live.

Moreover, according to the NGO manager, trust is necessary when preparing financial plans, as social welfare centers may be afraid of cost increases and should trust that cost calculations presented by NGOs are adequate to their needs. An issue of trust can also exist from NGOs towards the city hall. Distrust can arise, for example, as a result of not maintaining agreements which have been set during meetings even when documentation from meetings is kept. Undermining trust in the city officials may occur when the system of assistance is too complex. At times, a situation of not sharing information with social welfare centers can occur in order to have a reason not to provide aid. In the case of the interviewed manager of the NGO, trust in social welfare center is increased as “they help us fight for the person”. A decrease in the level of trust in social welfare centers may stem from the fact that “employees of social welfare centers should check what is happening with their clients” but they are not doing that.

With respect to the question of whether trust in an employee of another institution depends on personal traits of the employee an answer that “to some extent, simultaneously to nonprofit organizations and social welfare centers” as an employee of NGO would not “for many reasons direct the homeless under care of Ms. X, but would under care of Ms. Y, because the latter is a person who has a positive attitude towards the homeless, does not say ‘I was hoping they died’, and shows empathy for the homeless”. From the point of view of employees of shelters engaged in providing assistance to the homeless, “personnel should be loyal to the people they care for” or “together we fight for a homeless person”. Problems are fixed by rules and regulations which the employee must fulfill, that is, “social welfare center employee cannot rationalize the help, while the NGO has such a possibility. For example, if a homeless person lost money on a previous day due to their own fault, a nonprofit organization can withdraw help, whereas a social welfare center cannot withdraw the help. As in a family (i.e., real home) also in the shelter the assistance can be withdrawn for the better good.” In the perception of NGOs “the clerk is not a decision taker, since they must provide assistance based on law”.

In an answer to the question, is the quality of information obtained by social welfare centers from nonprofit organizations important, the interviewee stated, “the documents show how the clerk will behave, whether that person will try to get rid of the problem as soon as possible, or whether they will try to really assist the homeless. Some clerks phone the NGO for an additional explanation.” The interviewee said, “the sentences can show if someone wants to help the homeless. Problems can also arise in the case of clients who have real estate, but due to, for example, mental illness cannot stay there. If the social welfare center employee would trust the nonprofit organization there would be a chance to provide a person with mental illness with housing in social housing for the time being instead of throwing the person out of the shelter due to their available housing”.

As to the question regarding the flow of information, the interviewer received an answer “that all depends on the relationship. If there are many procedures, then social welfare centers will not be effective, there must be trust because without it nothing can be done for a homeless person. In our city, the local government created such laws that social welfare centers are no longer effective, and therefore trust is necessary.” Furthermore, the question regarding benevolence from employees of cooperating organizations and trust in them received confirmation that it is a significant factor in the relationship. Interviewees said, “one of the factors which can shape trust can be benevolence, for example, if a document is lost, if there is no empathy from the clerk then we can be afraid to try to resolve the issue.”

The interviewee emphasized that common values are a very important component of trust in the case of nonprofit organizations and social welfare centers alike as “independently of the organizational membership (religious organization or other) helping the homeless is the most important value and this approach creates trust in the institution. Even during the employee recruitment to nonprofit organizations following a check of professional qualifications, the approach towards a human being is also verified.”

Knowledge and competences “are important but they can be supplemented if there is trust and thirst for knowledge, then, we can ensure that the inadequacies will be levelled out.”

The frequency of contact is essential as ”the employees of our shelter have known employees of other nonprofit organizations for a long time and thanks to this the Assistance Board for the Homeless has been in existence for 25 years, however, the social welfare centers are generally alienated from this.”

According to the NGO manager, the frequency of contact does not increase trust as “sometimes a clerk tries to prove something and says that our NGO has filed 10 applications for social housing and so why he is doing it again on behalf of another colleague, while from the perspective of the NGO, earlier contacts have no connection with the issue at hand.”

The promptness is also important as “we can like someone very much but if a social worker does not meet the deadlines, for example, the interview with the homeless person is done at the last legally permitted moment and this causes a three week delay in payment of social benefits, this will cause the trust to be undermined.” On the other hand, a situation is possible “when we know that the social welfare center employee is trying hard and this clerk tells us that at the moment they have got a lot of work and they will provide us with a date within a legal deadline, then our trust in that person will not be damaged.”

When building trust, emotional aspects are also important as there is “no trust if the assistance is based only on fulfilling rules and regulations but not on actual help. For example, in one nonprofit organization there was a homeless person from another city, and thus that person had a right to apply for a place in social welfare home in that city. Because we trusted the social welfare center employee from another city, as this clerk in warm words described the conditions in social welfare home in that city (we have a beautiful garden, beneficiaries travel ), the NGO employee was able to persuade the homeless that he would have good conditions there, but we had to use emotions not procedures. Such an emotional approach, centered on the human being, makes a connection between satisfaction and cooperation”. The interviewee emphasized, “if someone tries and talks about emotions, then even if he is unable to take care of something for the homeless due to legal restrictions, they will say that they we unable to provide the help but feels bad because of it and in that case we will continue to trust that person.”

We chose determinants, which can influence trust at the NGOs, based on the literature overview and conducted empirical research, and we decided to use the same set of variables as in the case of social welfare centers, being aware that some variables could mean something different for both types of institutions.

4.2.2. The Results of the Surveys in the NGOs

Further support of the results is provided by the analysis of data from surveys from the perspective of the NGOs. The distributions of some important variables from the perspective of the NGOs are presented in the

Table 4. Most of the variables have a left skewed distribution, only the variables, trust in relation to social welfare centers’ employees (in 2013), and satisfaction from cooperation with other NGOs (in 2018), have a slightly right skewed distribution.

In the case of the NGOs, the average overall assessment of effects and the average overall assessment of the system have slightly improved (from 3.94 to 4.3 and from 3.86 to 4.57, respectively, on a seven-point scale between 2013 and 2018), but again, the differences cannot be determined in the distributions of these variables based on the Mann–Whitney U test. The evaluation of these effects for the NGOs is slightly larger than it was for the social welfare centers. No differences were found in the distributions of the remaining variables examined between the years analyzed. In the whole sample of NGOs employees, the percentage of females in the NGO sample tested is 76.9%, the percentage of people aged 25 years and below 30 years is 17.3%, aged 30 years and below 40 years is 36.5%, aged 40 years and below 50 years is 25%, and 50 years and below 65 years is 15.4%. In the research sample 19.6% of people possessed a B.A. education, while 62.7% had a M.A.

It is surprising how strongly similar the correlation results are in both analyzed periods in the case of, to some extent, dissimilar employees. The responses of the NGO employees regarding their assessment of other institutions, and therefore the correlations between trust and other variables were almost identical in 2013 and 2018.

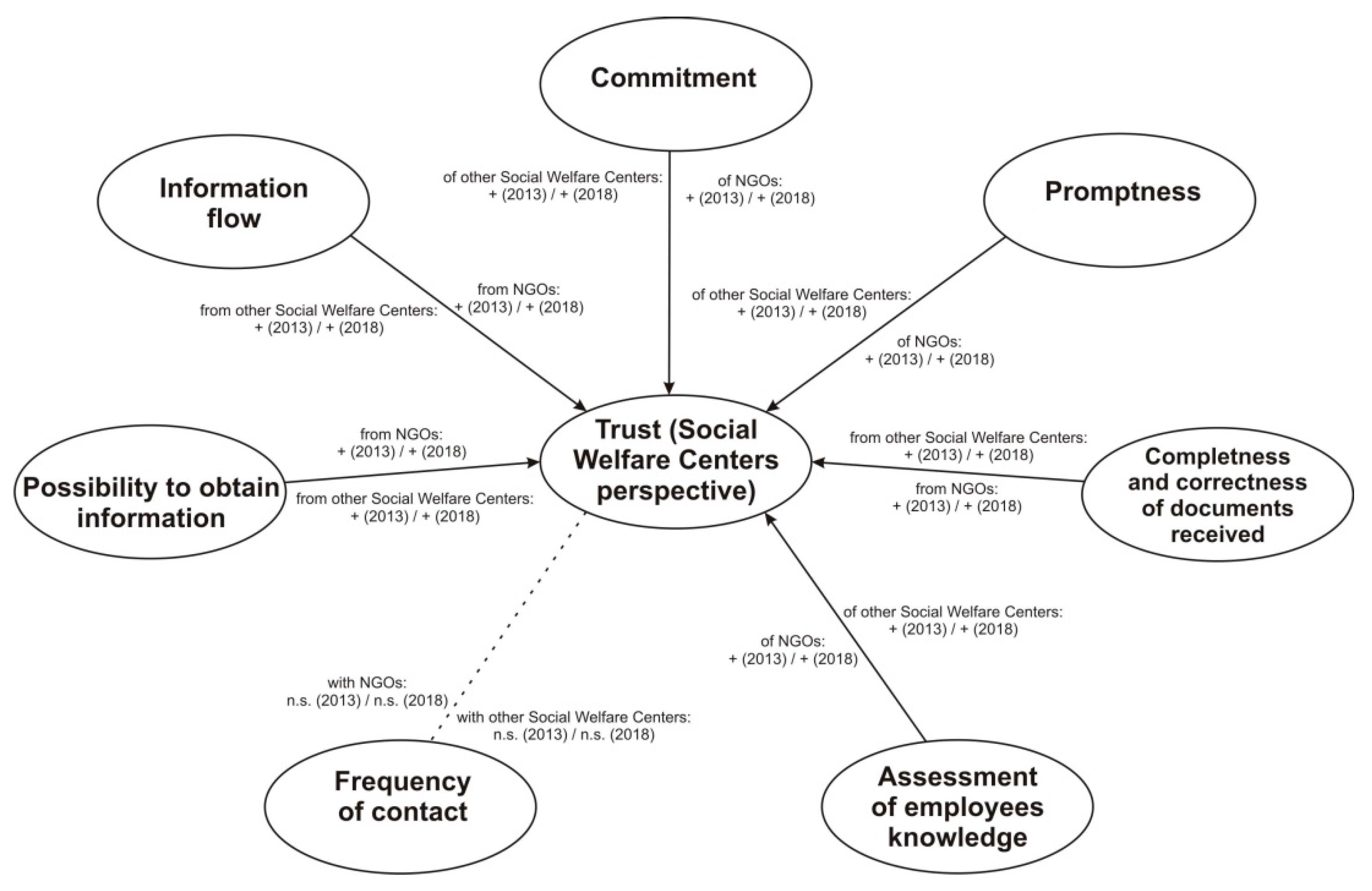

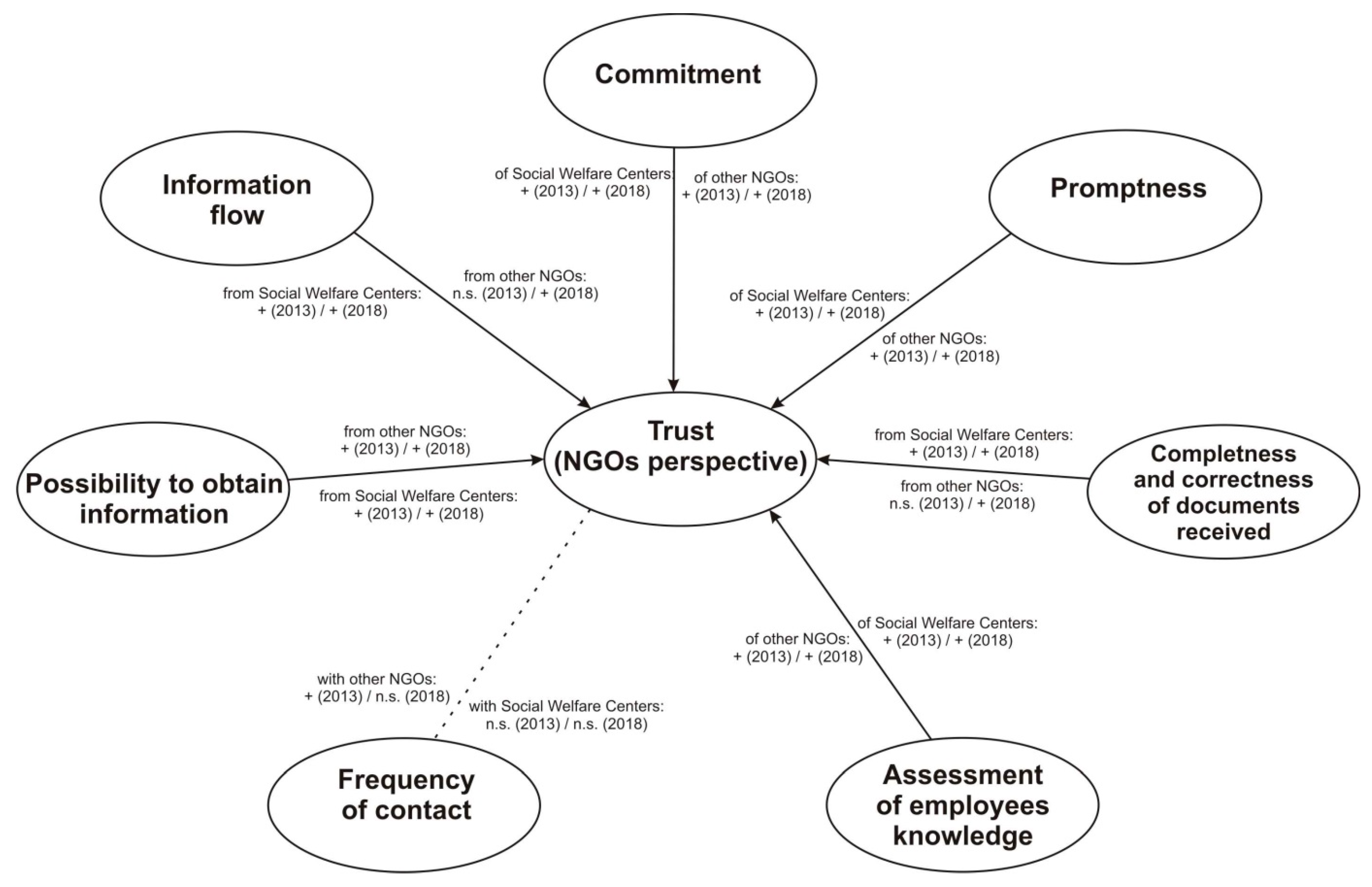

In the case of assessments of relationships with social welfare centers made from the perspective of the NGOs (see

Table 5), trust was correlated with assessment of the ability to obtain information from social welfare centers at the level of 0.618 in 2013 and 0.445 in 2018; assessment of information flow from social welfare centers at the level of 0.617 in 2013 and 0.635 in 2018; assessment of promptness of social welfare centers at the level of 0.733 in 2013 and 0.626 in 2018; assessment of commitment of welfare service centers at the level of 0.533 in 2013 and 0.592 in 2018; assessment of completeness and correctness of documents from social welfare centers at the level of 0.447 and 0.466, respectively; and assessment of knowledge of employees of welfare service centers at the level of 0.549 and 0.540, respectively.

Furthermore, very similar results were obtained in correlations among the assessment of NGOs trust and other variables regarding relationships with other NGOs (see

Table 6). A correlation with relation to assessment of the possibility to obtain information from other shelters was at a level of 0.532 in 2013 and 0.283 in 2018, however, other variables also proved to be significant, which included the following: assessment of promptness of other shelters at a level of 0.486 in 2013 and 0.613 in 2018; assessment of commitment of other shelters at a level of 0.508 and 0.419, respectively; and assessment of knowledge of employees of other shelters at a level of 0.627 and 0.458, respectively. In the case of the variable, assessment of information flow from other shelters, it proved not to be significant in 2013 but significant in the cohort of 2017 to 2018. After combining two research samples this correlation again proved to be significant. A similar result was obtained for the variable, assessment of completeness and correctness of documents from other shelters, which was insignificant in the study conducted in 2013 but significant in the 2018 sample and identically significant when the two research samples were combined. In the case of the NGOs research in 2013, a correlation between trust and a frequency of contact with other shelters proved to be significant at that time, but not significant in 2018, however, significant for the two combined samples.

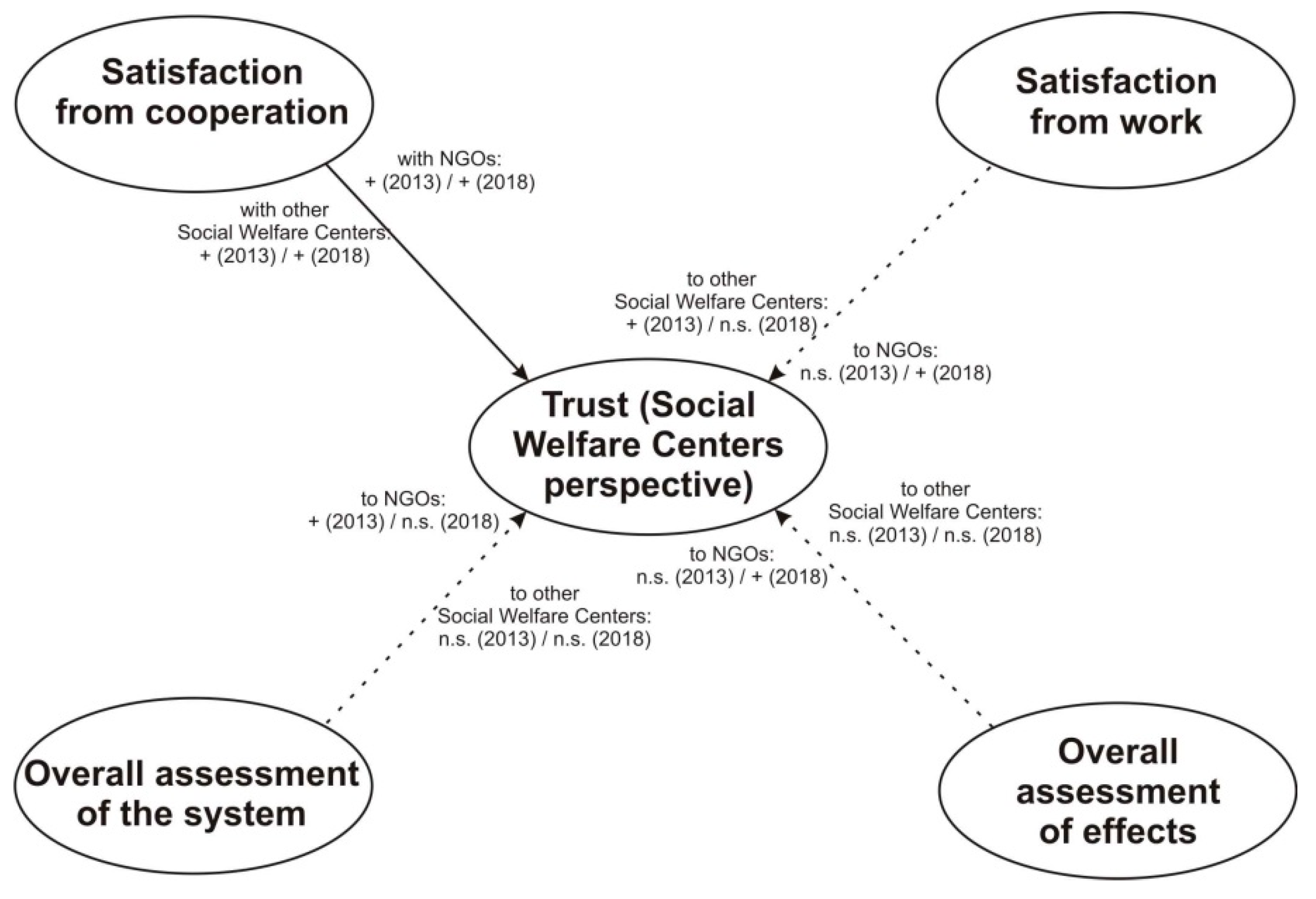

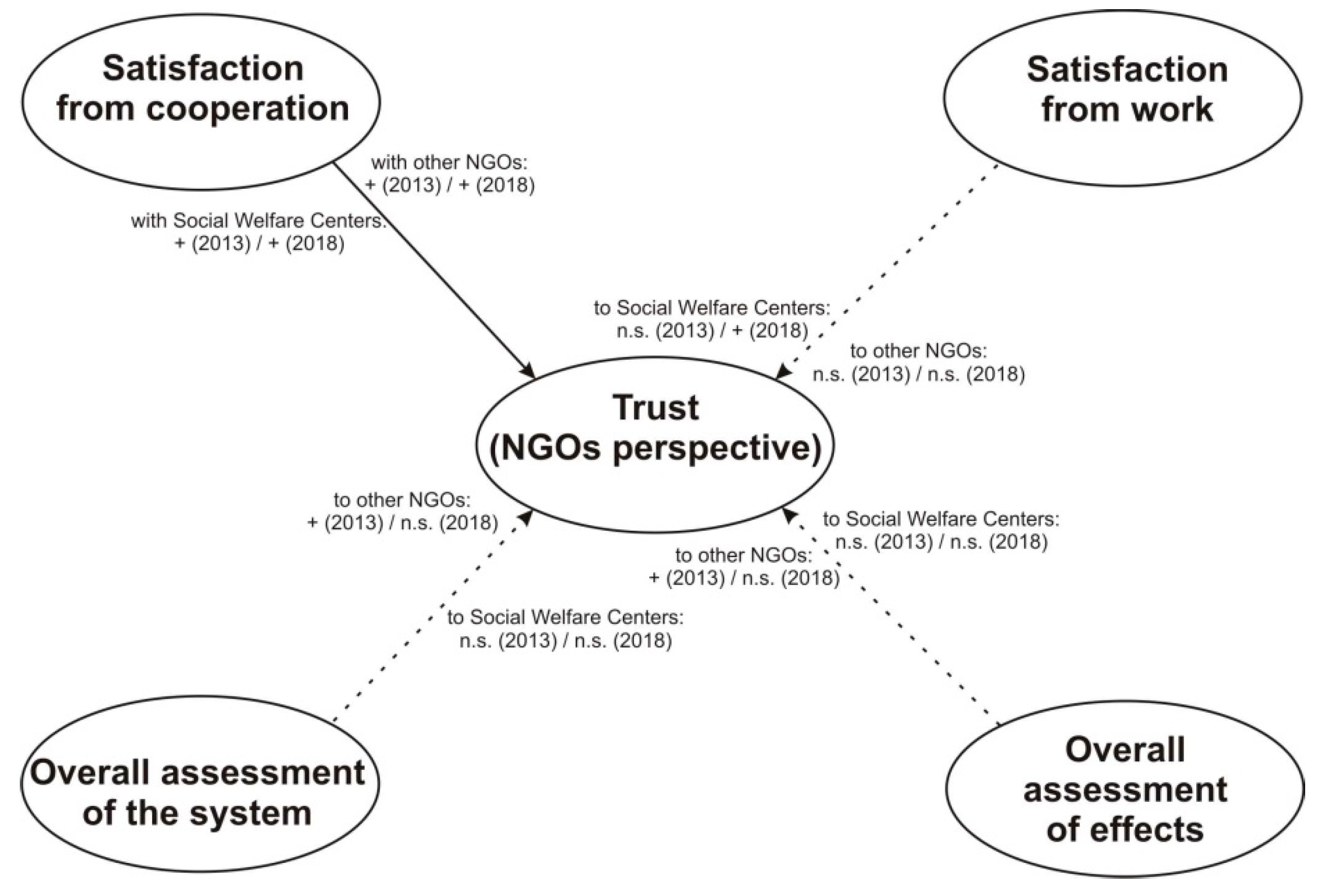

Furthermore, it should be emphasized that some correlations that were insignificant in the second phase of the study, could be treated as significant at a less conservative level of 10%. Trust proved not to be correlated with control variables such as gender, age, and education in both research samples at both points in time. Therefore, we conclude that control variables had no impact on differentiation in the research sample. The sample, with respect to control variables such as gender and position, was homogeneous, as the sample included mostly women in managerial roles at the NGOs and social workers at the social welfare centers. Additional control variables used in the study included the following: satisfaction from work, satisfaction from cooperation with other social welfare centers in Warsaw, satisfaction from cooperation with NGOs, overall assessment of effects, and overall assessment of the system. Correlations between trust and perceived outcome variables proved, in most cases, to be insignificant which allowed us to conduct the analysis without dividing the sample. The analysis has shown that due to the difficulty of the serviced client, it is not possible to obtain great and quick outcomes, and therefore (as expected) trust is not correlated with perceived outcome.

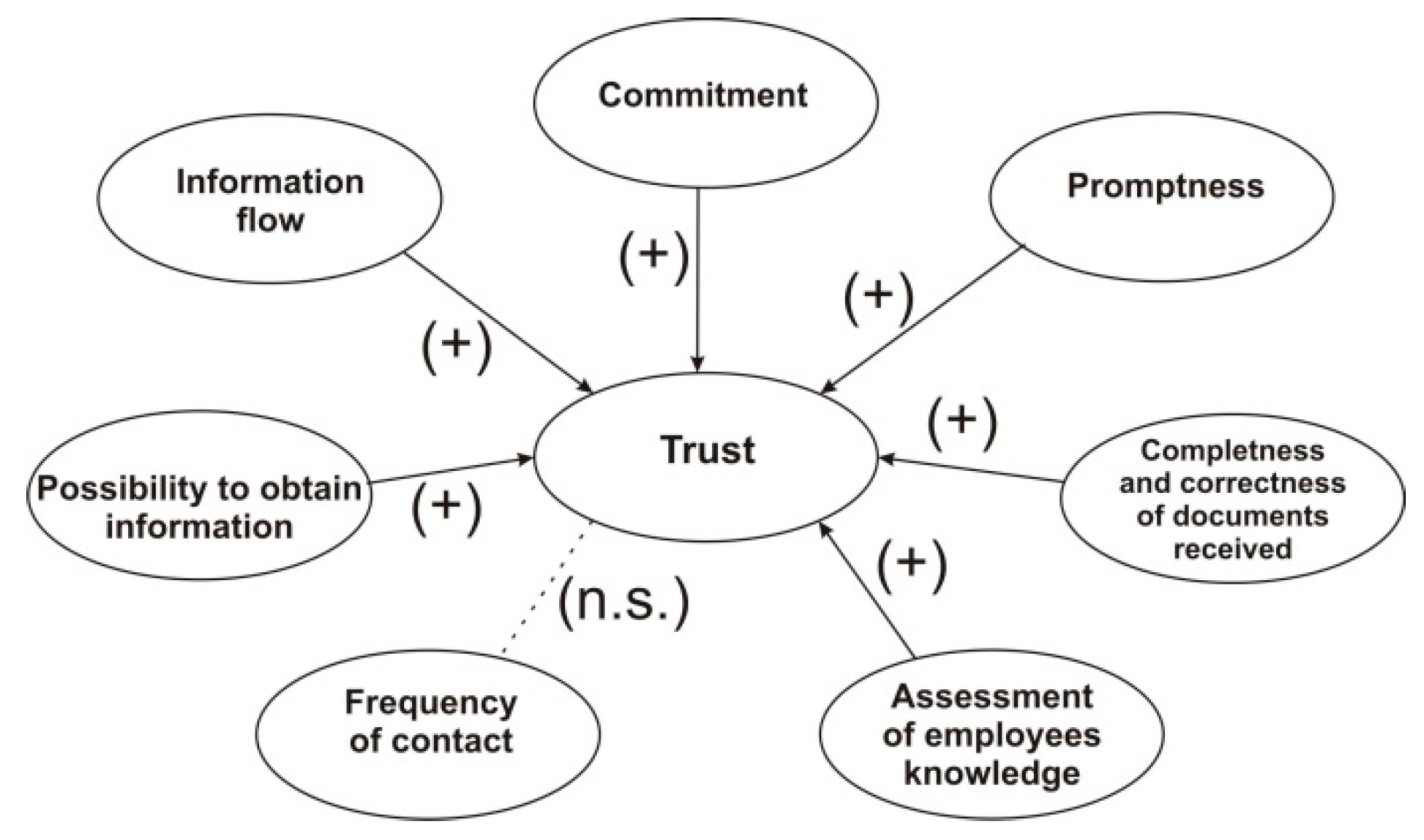

Figure 3 presents a summary of correlations among trust from the perspective of the NGOs and variables pertaining to perceived organizational effectiveness including the variable “frequency of contact”.

A fixed correlation between trust from the perspective of the NGOs and perceived organizational effectiveness in relation to social welfare centers is clearly visible. Nonetheless, the relationship between trust from the perspective of the NGOs and the frequency of contact shows that such a correlation generally does not exist.

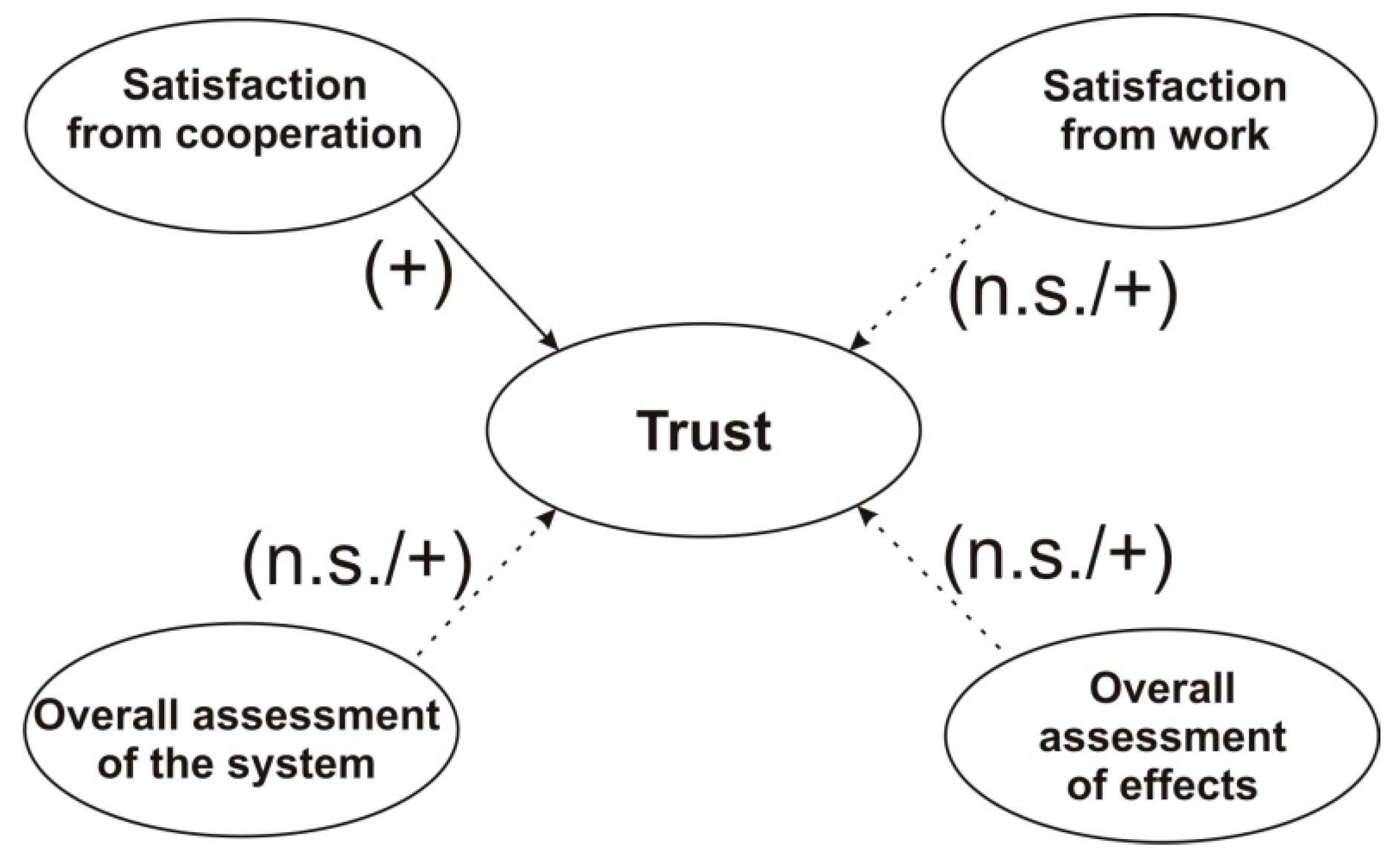

Figure 4 shows correlations among trust from the perspective of the NGOs and variables pertaining to the perceived outcomes of the network. All correlations prove to be statistically significant only in the case of the relationship between trust and satisfaction from cooperation.