The Truth behind the Brexit Vote: Clearing away Illusion after Two Years of Confusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Brexit: Development and Process

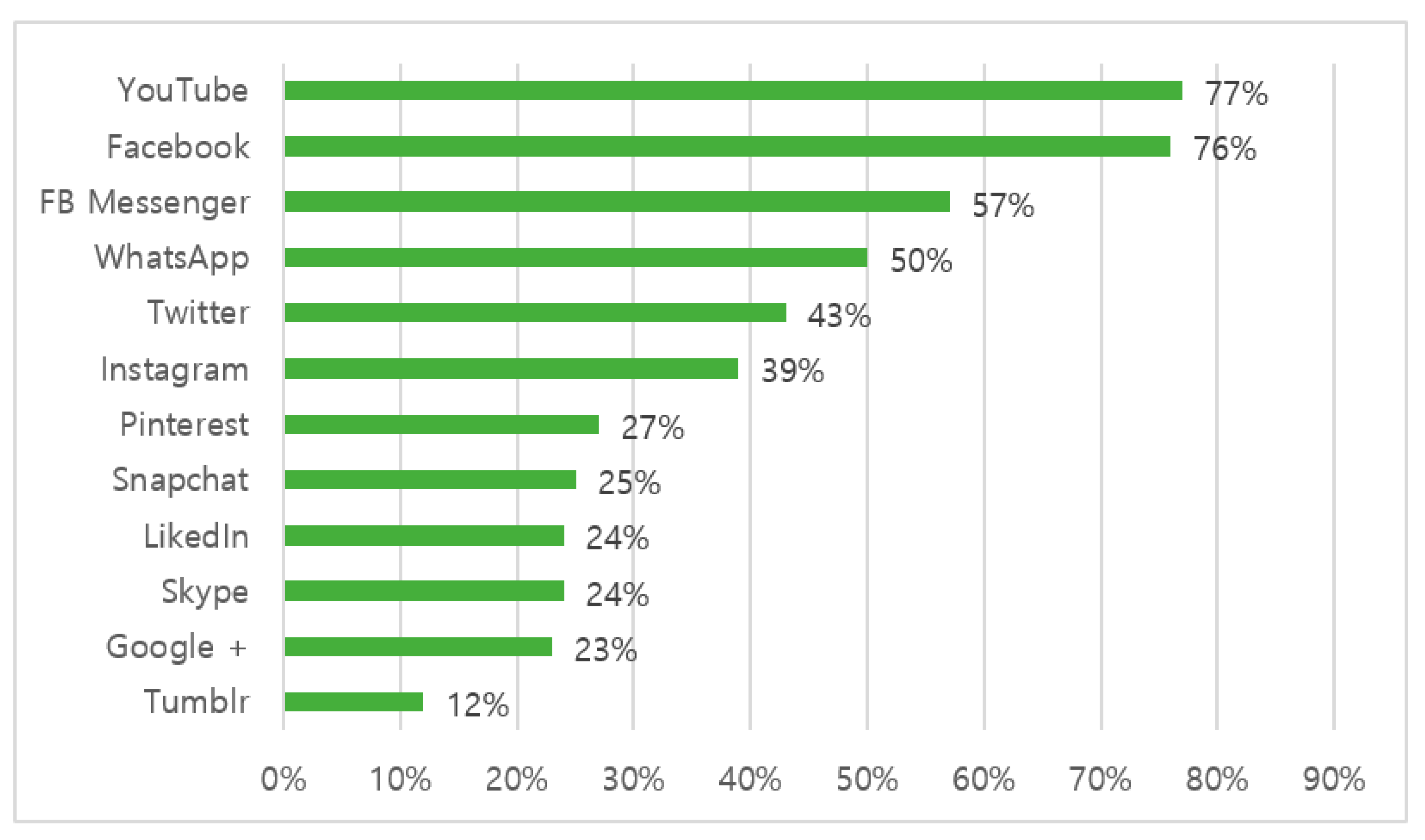

2.2. Brexit: Empirical Studies

3. Theoretical Background and Methodology

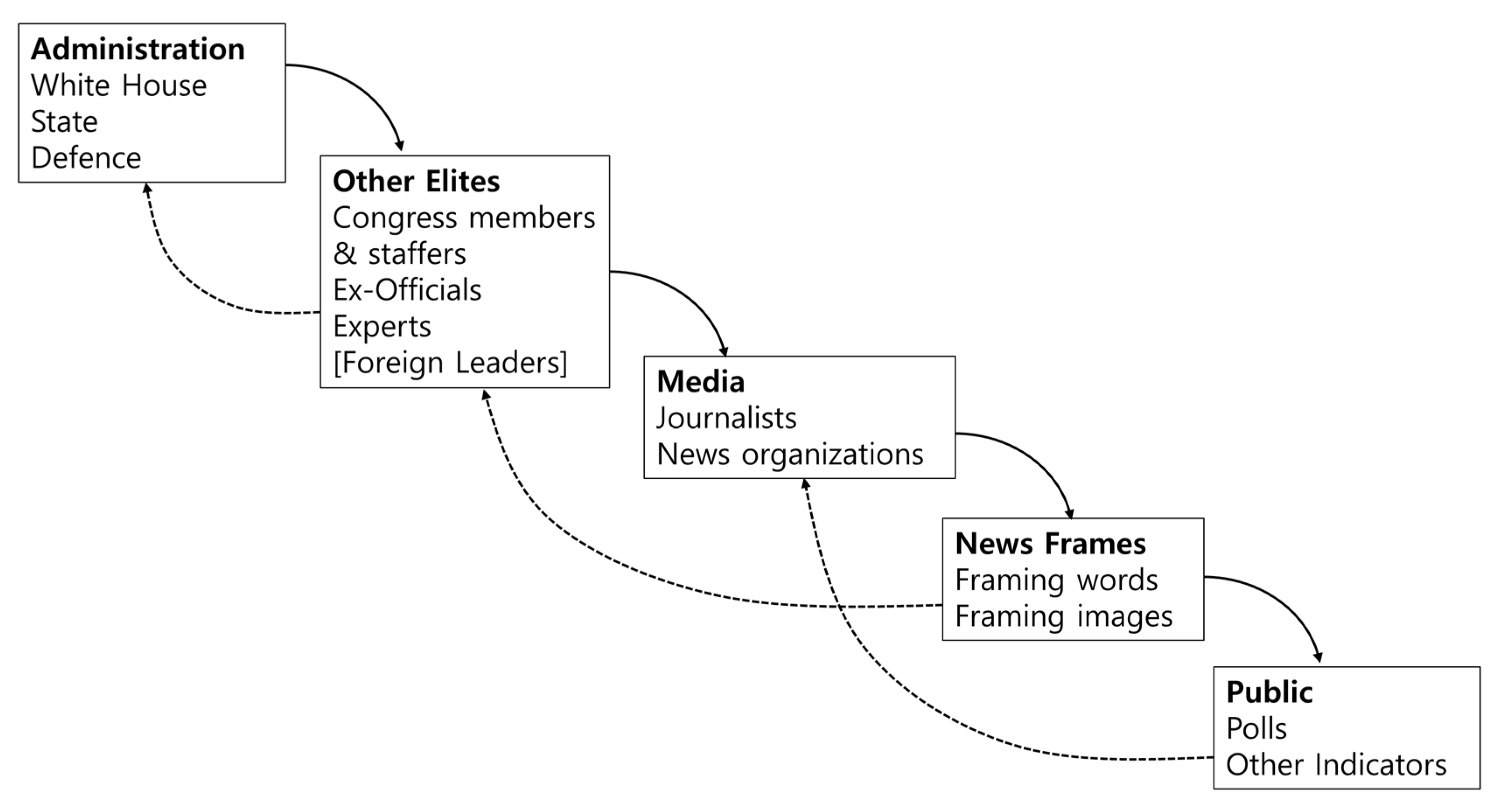

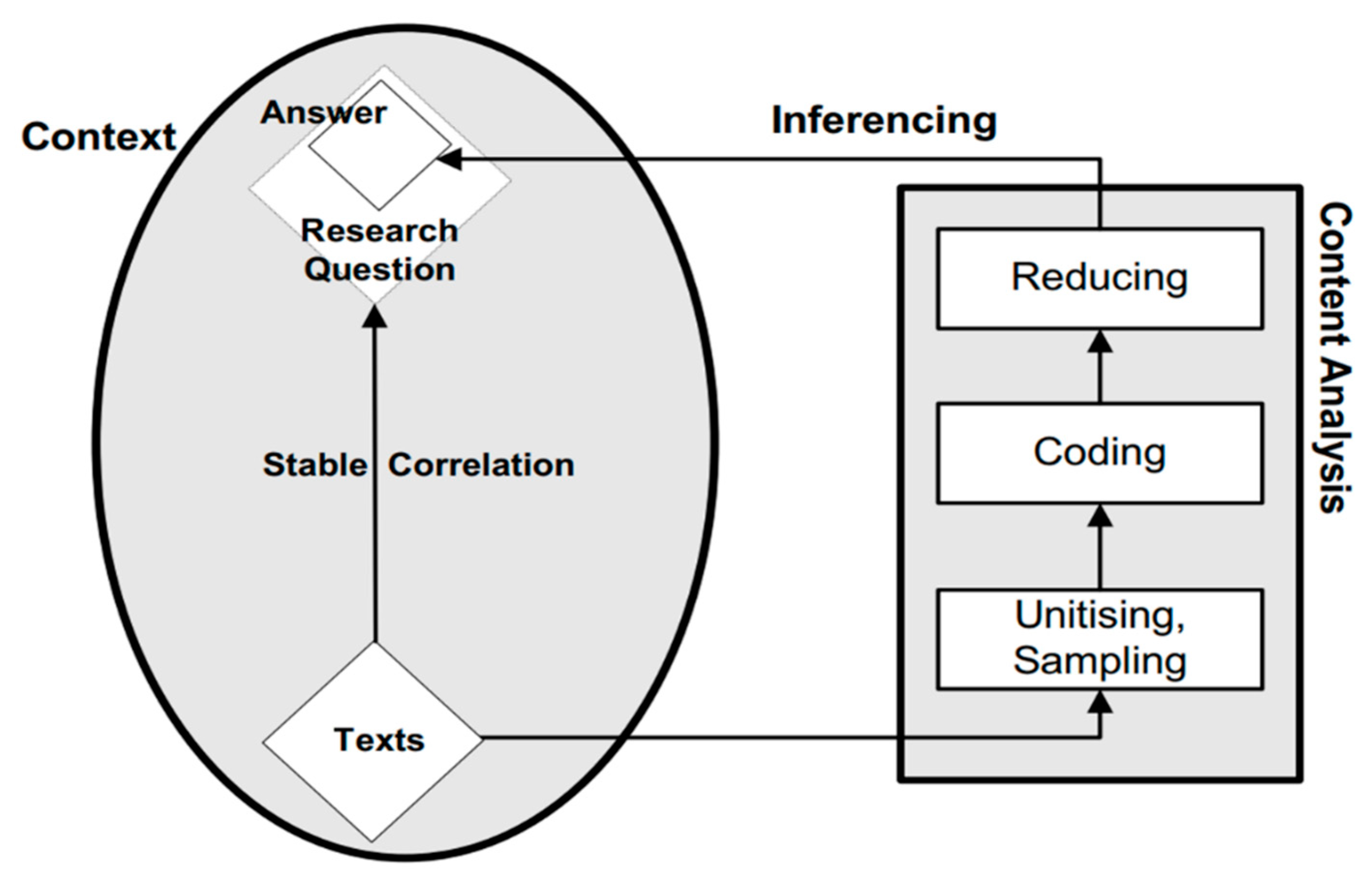

3.1. Framing

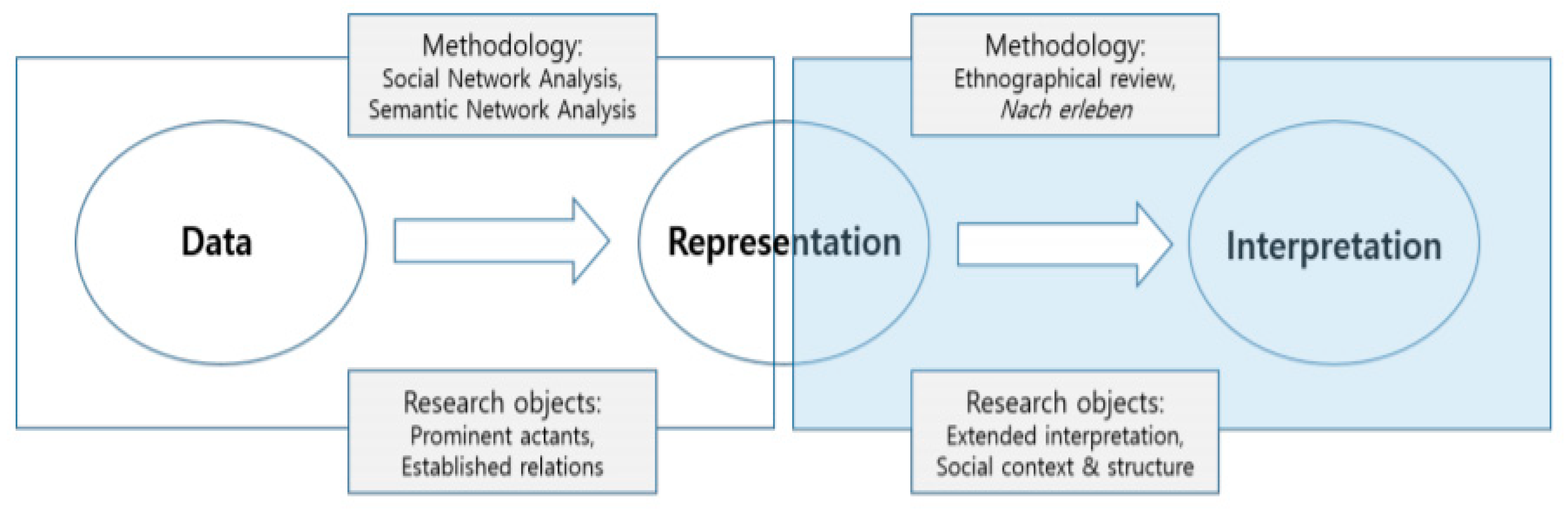

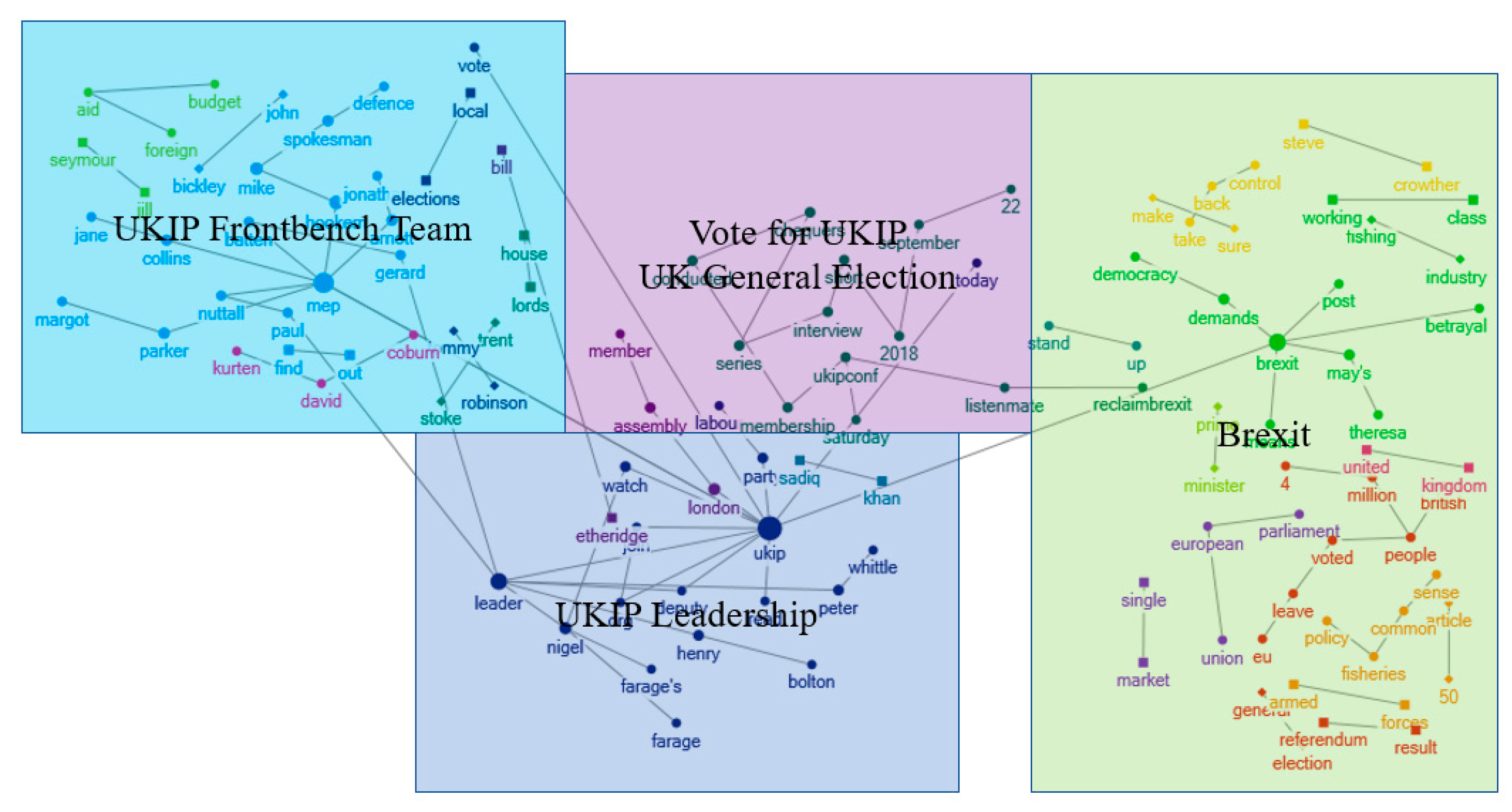

3.2. Semantic Network Analysis

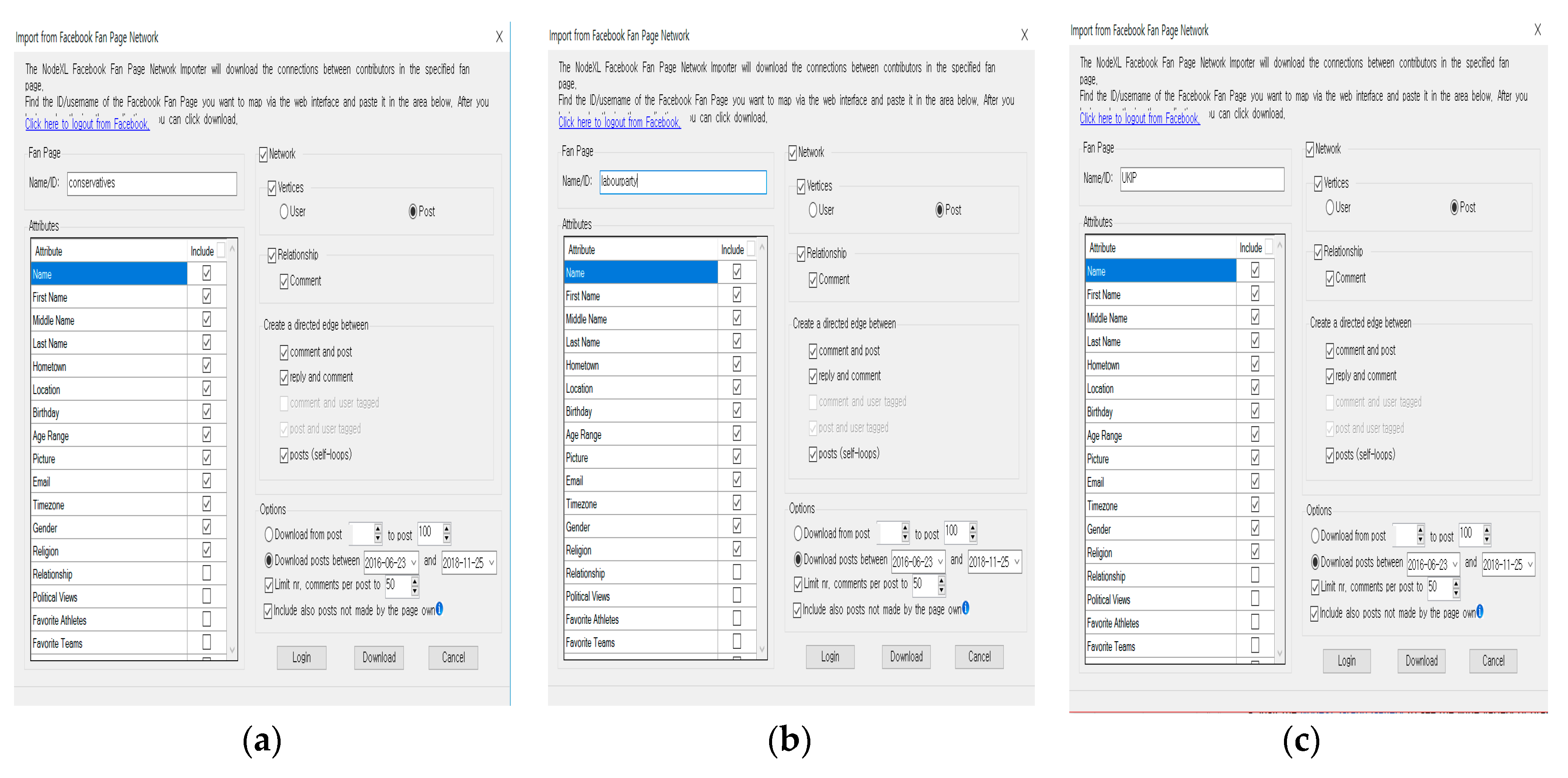

3.3. Research Methodology

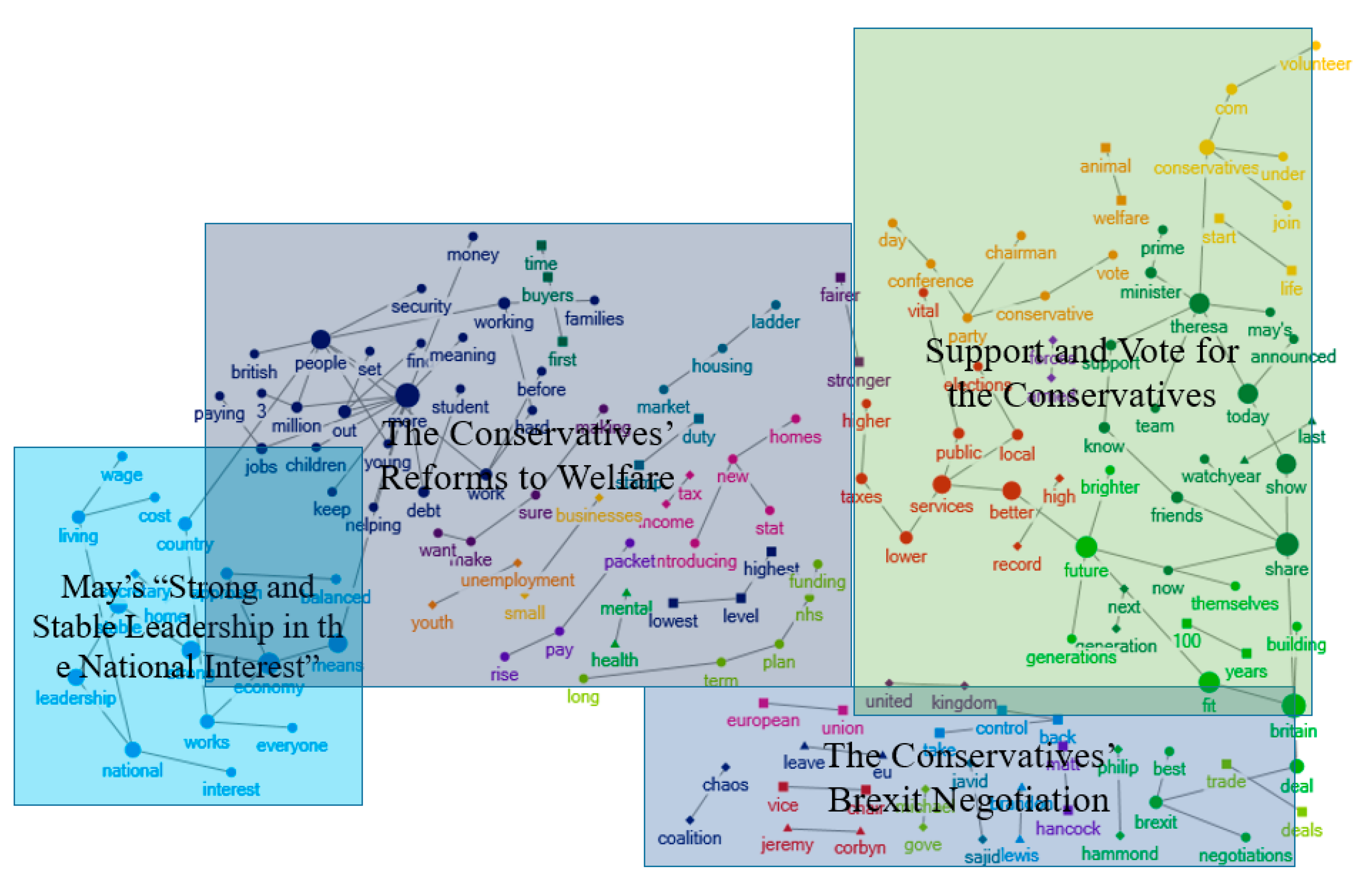

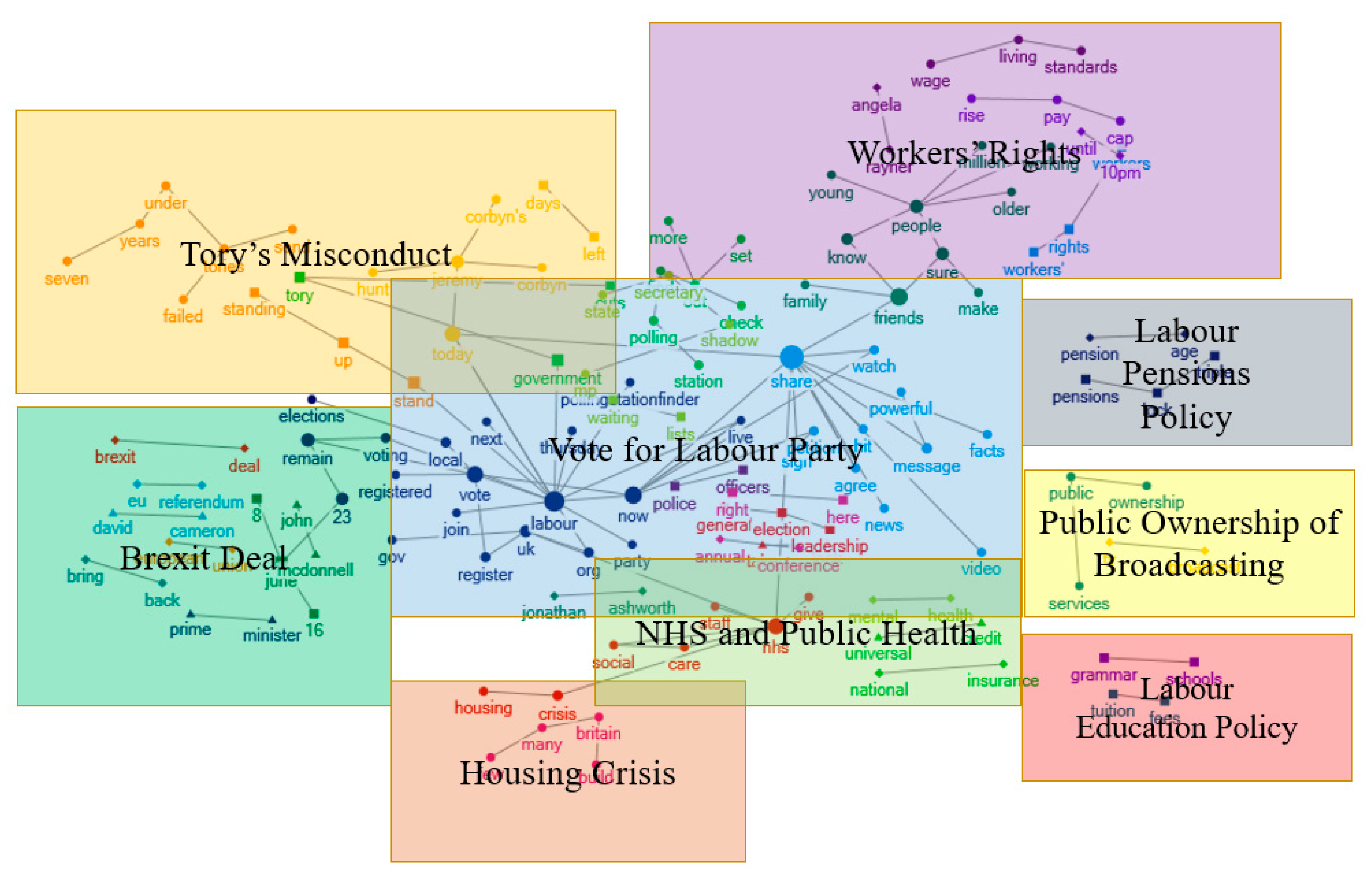

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Llwellyn, C.; Cram, L. The Results Are in and the UK Will #Brexit: What Did Social Media Tell Us about the UK’s EU Referendum? EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. Available online: http://www.referendumanalysis.eu/ (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Office for National Statistics. Internet Access—Households and Individuals, Great Britain: ONS. 7 August 2018. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2018 (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- We Are Social, Global Digital Report 2018. Available online: https://digitalreport.wearesocial.com/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Bale, T. Who leads and who follows? The symbiotic relationship between UKIP and the Conservatives—and populism and Euroscepticism. Politics 2018, 38, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hong, J. The Rise of Euroscepticism and Internal Nationalism in the Westminster Democracy―The Questions of the 2015 British Parliamentary Election. Korean J. Br. Stud. 2015, 33, 197–233. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002008268 (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Travis, A. The Leave Campaign Made Three Key Promises—Are They Keeping Them? The Guardian, 27 June 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/27/eu-referendum-reality-check-leave-campaign-promises (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Full Fact, UK’s EU Membership Fees. Available online: https://fullfact.org/europe/our-eu-membership-fee-55-million/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Johnson, B. The Only Way to Take Back Control of Immigration Is to Vote Leave. Vote Leave Take Control. 23 June 2016. Available online: http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/boris_johnson_the_only_way_to_take_back_control_of_immigration_is_to_vote_leave_on_23_june.html (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Ammerman, P. The Effectiveness of UKIP Campaign Advertising. Navigator, 26 June 2016. Available online: http://www.navigator-consulting.com/articles/the-effectiveness-of-ukip-campaign-advertising/74 (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Portes, J. Immigration, Free Movement and the EU Referendum. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2016, 236, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N. ‘Brexit Means Brexit’: Theresa May and Post-Referendum British Politics. Br. Politics 2018, 13, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copus, C. The Brexit Referendum: Testing the Support of Elites and their Allies for Democracy; Or, Racists, Bigots and Xenophobes, Oh My! Br. Politics 2018, 13, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, H.; Goodwin, M.; Whiteley, P. Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D. Brexit and the Politics of Truth. Br. Politics 2018, 13, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. Brexit, the Left Behind and the Let Down: The Political Abstraction of ‘The Economy’ and the UK’s EU Referendum. Br. Politics 2018, 13, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafts, N. The Growth Effects of EU Membership for the UK: A Review of the Evidence. Social Market Foundation Global Perspectives Series Paper 7. 2016. Available online: http://www.smf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SMF-CAGE-The-Growth-Effects-of-EU-Membership-for-the-UK-a-Review-of-the-Evidence-.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Dhingra, S.; Sampson, T. “Life after Brexit: What Are the UK’s Options Outside the European Union?”. CEP Brexit Analysis No. 1. 2016. Available online: http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/brexit01.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Dhingra, S.; Ottaviano, G.; Sampson, T.; Van Reenen, J. The Impact of Brexit on Foreign Investment in the UK. CEP Brexit Analysis No. 3. 2016. Available online: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/brexit03.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Sampson, T. Brexit: The Economics of International Disintegration. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudgin, G.; Coutts, K.; Gibson, K.; Buchanan, J. The Role of Gravity Models in Estimating the Economic Impact of Brexit; Working Paper No. 490; Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Available online: http://www.cbr.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/centre-for-business-research/downloads/working-papers/wp490.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Coutts, K.; Gudgin, G.; Buchanan, J. How the Economic Profession Got It Wrong on Brexit; Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge Working Paper No. 493; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Available online: http://www.cbr.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/centre-for-business-research/downloads/working-papers/wp493.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Jackson, D.; Thorsen, E.; Wring, D. EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. 2016. Available online: http://www.referendumanalysis.eu/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Usherwood, S.; Wright, K. Talking Past Each Other: The Twitter Campaigns. EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. 2016. Available online: http://www.referendumanalysis.eu/eu-referendum-analysis-2016/section-7-social-media/talking-past-each-other-the-twitter-campaigns/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Mullen, A. Leave Versus Remain: The Digital Battle. EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. 2016. Available online: http://www.referendumanalysis.eu/eu-referendum-analysis-2016/section-7-social-media/leave-versus-remain-the-digital-battle/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Vasilopoulou, S. Campaign Frames in the Brexit Referendum. EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. 2016. Available online: http://www.referendumanalysis.eu/eu-referendum-analysis-2016/section-8-voters/campaign-frames-in-the-brexit-referendum/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Khabaz, D. Framing Brexit: The Roe, and the Impact, of the National Newspapers on the EU referendum. Newsp. Res. J. 2018, 39, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, T. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.; Taylor, S. Social Cognition, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, D. Framing as a Theory of Media Effects. J. Commun. 1999, 49, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House’s Frame After 9/11. Political Commun. 2003, 20, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Kohring, M. The Content Analysis of Media Frames: Toward Improving Reliability and Validity. J. Commun. 2008, 58, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Attelveldt, W. Semantic Network Analysis: Techniques for Extracting, Representing and Querying Media Content; BookSurge Publishing: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, F.; Kleinnijenjuis, J.; Oegema, D.; Utz, S.; van Atteveldt, W. Strategic Framing in the BP Crisis: A Semantic Network Analysis of Associated Frames. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Evans, J.; Endle, C.M.; Solbrig, H.R.; Chute, C.G. Using Semantic Web Technologies for the Generation of Domain-Specific Templates to Support Clinical Study Metadata Standards. J. Biomed. Semant. 2016, 7, 3710–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, L.; Kim, N. Connecting Opinion, Belief and Value: Semantic Network Analysis of a UK Public Survey on Embryonic Stem Cell Research. J. Sci. Commun. 2015, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Chung, S. Promoting a World Heritage Site through Social Media: Suwon City’s Facebook Promotion Strategy on Hwaseong Fortress (in South Korea). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Chung, S. Semantic Network Analysis of Legacy News Media Perception in South Korea: The Case of PyeongChang 2018. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Media Research Foundation, NodeXL, Features. Available online: https://www.smrfoundation.org/nodexl/features/ (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- The Conservatives, Forward Together: The Conservative Manifesto. Available online: https://www.conservatives.com/manifesto (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Mason, R. Labour Voters in the Dark about Party’s Stance on Brexit, Research says. The Guardian, 30 May 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/may/30/labour-voters-in-the-dark-about-partys-stance-on-brexit-research-says (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- The Labour, Accessible Manifesto, Negotiating Brexit. Available online: https://labour.org.uk/manifesto/negotiating-brexit/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Zartaloudis, S. From U-Turn to U-Turn: Did Pro-Brexit Politicians Mislead the British Public? The University of Birmingham, Perspectives. Available online: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/perspective/brexit-eu-nationals.aspx (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Lakoff, G.; Wehling, E. Your Brain’s Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide; Andrews: Exeter, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Musolff, A. How metaphors can shape political reality: the figurative scenarios at the heart of Brexit. Pap. Lang. Commun. Stud. 2017, 1, 2–16. Available online: https://www.uea.ac.uk/documents/241631/16651997/pmus/5b49c7fe-c73d-4905-86e4-6bf3e6dab278 (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- YouGov. May’s Brexit Deal Leads in Just Two Constituencies as It Suffers from Being Everyone’s Second Choice. YouGov, 6 December 2018. Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2018/12/06/mays-brexit-deal-leads-just-two-constituencies-it- (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, M. The Ant-Colony as an Organism. J. Morphol. 1911, 22, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, P. Collective Intelligence: Mankind’s Emerging World in Cyberspace; Bononno, R., Ed.; Plenum Trade: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, S.W.; Kim, Y. The Truth behind the Brexit Vote: Clearing away Illusion after Two Years of Confusion. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195201

Chung SW, Kim Y. The Truth behind the Brexit Vote: Clearing away Illusion after Two Years of Confusion. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195201

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Sae Won, and Yongmin Kim. 2019. "The Truth behind the Brexit Vote: Clearing away Illusion after Two Years of Confusion" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195201

APA StyleChung, S. W., & Kim, Y. (2019). The Truth behind the Brexit Vote: Clearing away Illusion after Two Years of Confusion. Sustainability, 11(19), 5201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195201