Stakeholders of Cultural Heritage as Responsible Institutional Tourism Product Management Agents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Issue

2.1. Governance and Stakeholders in the Cultural Heritage

“common elements emphasized are co-operation to enhance legitimacy, the effectiveness of governing societies, new processes and public–private arrangements”.

“the way in which power is exercised in the management of economic and social resources for the development of a country. Good governance is summarized, among other things, in the development of policies with open information flows”.

2.2. Stakeholders, Strategies, and Tourism Management

2.3. Cultural Heritage and Stakeholders

2.4. Museums and Stakeholders

“The stakeholders of a museum are individuals or organizations that have an interest or influence in the capacity of a museum to achieve its objectives”.

2.5. Responsible Cultural Tourism Product

3. Methodology and Case Studies

3.1. Case Studies

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Strategic Management

4.1.1. Strategic Management of the Real and Potential Stakeholders in the Painted Cave

4.1.2. Strategic Management of Real and Potential Stakeholders in the Néstor Museum

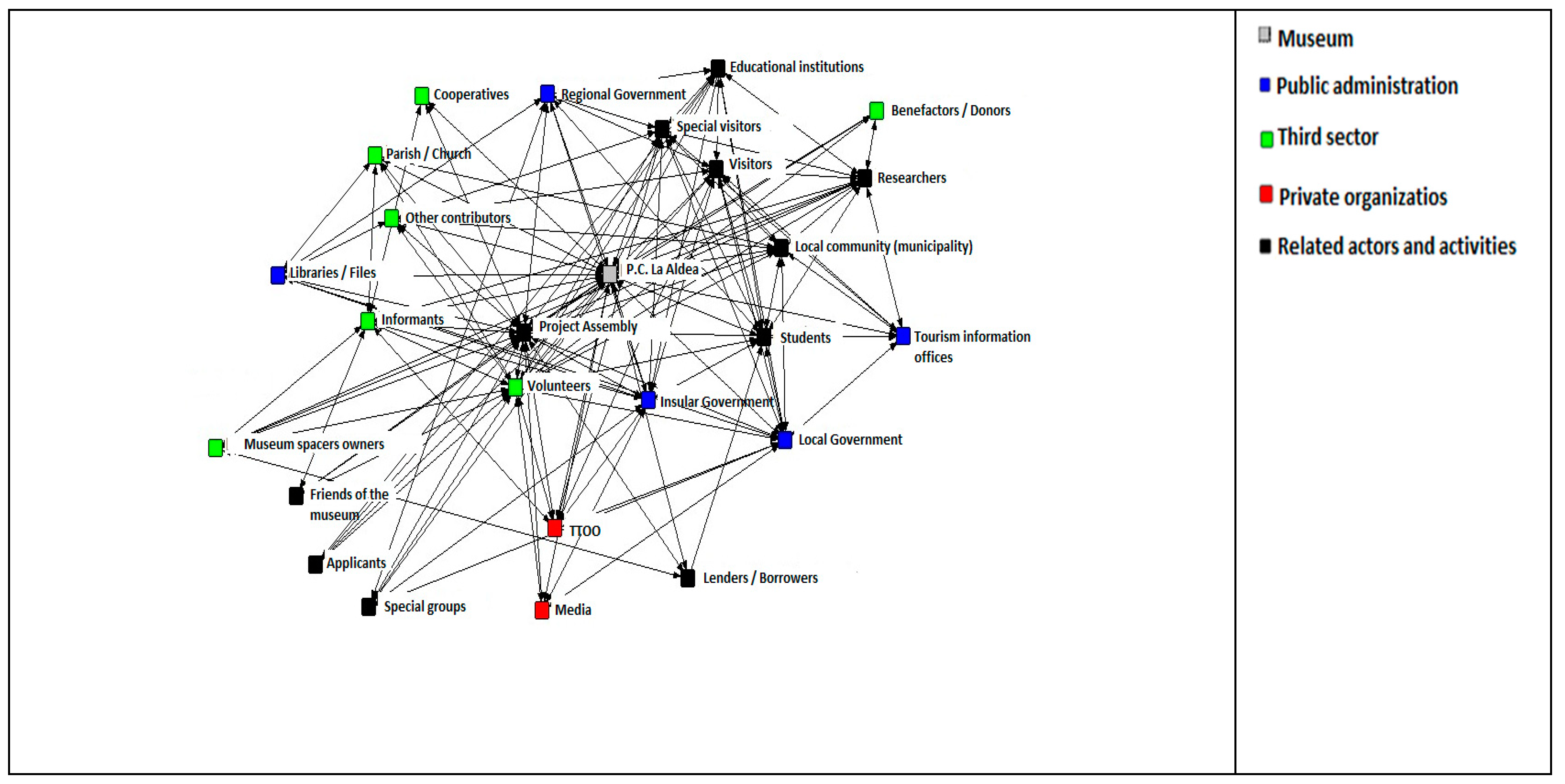

4.1.3. Strategic Management of Real and Potential Stakeholders in the Cultural Project of Community Development of La Aldea

4.1.4. Strategic Management of the Real and Potential Stakeholders in the Cenobio de Valerón

4.2. Analysis of the Results

4.2.1. Governance and Stakeholders in the Case Studies

4.2.2. Stakeholders

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, K. Museum Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Soren, B.J. Museums experiences that change visitors. Museum Manag. Curatorship 2009, 24, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerquetti, M. More is better! Current issues and challenges for museum audience development: A literature review. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2016, 6, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. Responsible Tourism: Using Tourism for Sustainable Development Goodfellow, 2nd ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayadasa, K.H.J. Governance, Heritge and Sustainability; Sarasavi Publishers: Nugegoda, Sri Lanka, 2012; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Yang, T.C. Democracy, rule of law, and corporate governance—A liquidity perspective. Econ. Gov. 2017, 18, 35–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, L.; Walker, D.H. Visualising and mapping stakeholder influence. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, M.; Lehman, K. Communicating sustainability priorities in the museum sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reussner, E.M. Strategic Management for Visitor-oriented Museums. Mus. Manag. Mark. 2007, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T.; Boukas, N.; Christodoulou-Yerali, M. Museums and cultural sutainability: Stakeholders, forces and cultural policies. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2014, 20, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, V.; Costa, C.A. Explicating inter-organizational linkages of a host community’s events network. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2010, 1, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J. Societal governance. In Demokratien in Europa; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2003; pp. 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Unesco. Gestión del Patrimonio Mundial Cultural. Manual de Referencia; Unesco: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: whc.unesco.org/document/130490 (accessed on 22 September 2019).

- Shipley, R.; Kovacs, J. Good governance principles for the cultural heritage sector: Lessons from international experience. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 8, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C. From Indicators to Governance to the Mainstream: Tools for Cultural Policy and Citizenship. Accounting for Culture: Examining the Building Blocks of Cultural Citizenship; University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- San-Jose, L.; Retolaza, J.L. Participación de los stakeholders en la gobernanza corporativa: Fundamentación ontológica y propuesta metodológica. Universitas Psychologica 2012, 11, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá, J.P. De la Burocracia al Management, del Management a la Gobernanza. Las Transformaciones de las Administraciones Públicas en Nuestro Tiempo; (Estudios Goberna), Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública. Ministerio de Administraciones Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J.W. Ética en los Negocios Un Enfoque de Administración de los Stakeholders y de Casos; Thomson Learning: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frooman, J. Stakeholder Influence Strategies. PhD Thesis, University of Pittsburg, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros De Araujo, L.; Bramwell, B. Stakeholder Assessment and Collaborative Tourism Planning: The Case of Brazil’s Costa Dourada Project. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautter, E.T.; Leisen, B. Managing Stakeholders A Tourism Planning Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Getz, D. Resource dependency, costs and revenues of a street festival. Tour. Econ. 2007, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Cortijo, G.I.; Hernández Mogollón, J.M. Los stakeholders del turismo. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Tourism & Management Studies, Algarve, Portugal, 14–17 November 2011; Volume 1, pp. 894–903. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, L.R.; Ritchie, J.B. Destination stakeholders exploring identity and salience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Newsome, D. Planning for stingray tourism at Hamelin Bay, Western Australia: The importance of stakeholder perspectives. Int. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Fernández, J.I. Las partes interesadas en la gestión turística de los parques naturales andaluces. Identificación de interrelaciones e intereses. Revista de Estudios Regionales 2010, 88, 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Matíaz Cruz, G.; Pulido Fernández, J.I. Dinámica relacional interorganizacional para el desarrollo turístico. Los casos de Villa Gesell y Pinamar (Argentina). Revista de Estudios Regionales 2012, 94, 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido Fernández, J.I. Turismo Cultural; Editorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martinell Sempere, A. Los Agentes de la Cultura. En Manual Atalaya. Apoyo a la gestión cultural. Universidad de Cádiz (Organizador). Available online: http://atalayagestioncultural.es/capitulo/agentes-cultura (accessed on 14 June 2017).

- Kotler, N.; Kotler, P. Estrategias y Marketing de Museos; Editorial Ariel Patrimonio Histórico: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Harper-Collins: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Legget, J. Mapping what Matters in New Zealand Museums. Stakeholders Perspectives on Museum Performance and Accountability. Thesis in Management and Museums Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Palmersten North, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chias Suriol, J. Del recurso a la oferta turístico cultural: Catálogo de problemas. In Proceedings of the I Congreso Internacional Del Turismo Cultural, Salamanca, Spain, 5–6 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Deldago, N.L. Planificación de Marketing y Adopción de Estrategias Comerciales. El caso del Parque Turístico Río Canímar. Master’s Thesis, Dpto. de Economía, Facultad de Ingeniería Industrial—Economía, Universidad de Matanzas Camilo Cienfuegos, Maatanaz, Cuba, 2011. Available online: http://revistas.uexternado.edu.co/index.php/tursoc/article/view/3396/3519 (accessed on 10 June 2017).

- Lord, B.; Lord, G.D. Manual de Gestión de Museos; Editorial Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ballart Hernández, J.; Juan I Tresserras, J. Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural; Editorial Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Querol, M.A. Manual de Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural; Ediciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bogartti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeeman, L.C. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Analysis; Analytic Technologies: Harvard, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Fernández, M.C.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. ¿Existe gobernanza en la actual gestión de los destinos turísticos ? Estudio de casos. PASOS: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2014, 12, 685–705. [Google Scholar]

- Merinero Rodríguez, R.; Zamora Acosta, E. La colaboración entre los actores turísticos en ciudades patrimoniales. Reflexiones para el análisis del desarrollo turístico. PASOS: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2009, 7, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? J. Sust. Tourism 2012, 21, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choices in Alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzi, B: Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Quaterly 1997, 42, 35–67. [CrossRef]

- Lasker, R.D.; Weiss, E.S.; Miller, R. Partnership Synergy: A Practical Framework for Studying and Strengthening the Collaborative Advantage. Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Reeve, J.; Woollard, V. The Responsive Museum: Working with Audiences in the Twenty First Century; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2012; pp. 1–276. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Whittington, R. Exploring Corporate Strategy, Text Cases; Organizational Change, Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008; p. 878. [Google Scholar]

- Bertacchini, E.E.; Dalle Nogare, C.; Scuderi, R. Ownership, organization structure and public service provision: The case of museums. J. Cult. Econ. 2018, 42, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Real Relationships | Potential Relationships |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Total relationships | 266 | 282 |

| 2 Density | 12.3% | 13.04% |

| 3 Distance | 1.838 | 1.870 |

| 4 Centrality | 5.66 | 6 |

| 5 Geodetic distance | 55.89% | 57.26% |

| Indicator | Real Relationships | Potential Relationships |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Total relationships | 94 | 104 |

| 2 Density | 6.69% | 7.4% |

| 3 Distance | 1.916 | 1.926 |

| 4 Centrality | 2.474 | 2.737 |

| 5 Geodetic distance | 91.51% | 89.79% |

| Indicator | Real Relationships | Potential Relationships |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Total relationships | 249 | 342 |

| 2 Density | 16.8% | 23.08% |

| 3 Distance | 1.617 | 1.769 |

| 4 Centrality | 6.385 | 7.671 |

| 5 Geodetic distance | 42.84% | 80.80% |

| Indicator | Real Relationships | Potential Relationships |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Total relationships | 141 | 175 |

| 2 Density | 9.04% | 11.22% |

| 3 Distance | 1.838 | 1.892 |

| 4 Centrality | 3.525 | 4.375 |

| 5 Geodetic distance | 65.74% | 62.45% |

| Category/Museum | Painted Cave | Nestor Museum | C. P. La Aldea | Cenobio de Valerón | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real (R)-Potential (P) | R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P |

| Public Administration | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 |

| Third Sector | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| Private Organizations | 11 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| Actors and related activities | 13 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 11 | 17 | 12 | 15 |

| Does not affect | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 10 | 5 |

| Total | 42 | 42 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 39 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno-Mendoza, H.; Santana-Talavera, A.; J. León, C. Stakeholders of Cultural Heritage as Responsible Institutional Tourism Product Management Agents. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195192

Moreno-Mendoza H, Santana-Talavera A, J. León C. Stakeholders of Cultural Heritage as Responsible Institutional Tourism Product Management Agents. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195192

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Mendoza, Héctor, Agustín Santana-Talavera, and Carmelo J. León. 2019. "Stakeholders of Cultural Heritage as Responsible Institutional Tourism Product Management Agents" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195192

APA StyleMoreno-Mendoza, H., Santana-Talavera, A., & J. León, C. (2019). Stakeholders of Cultural Heritage as Responsible Institutional Tourism Product Management Agents. Sustainability, 11(19), 5192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195192