Community-Based Governance and Sustainability in the Paraguayan Pantanal

Abstract

1. Introduction

Political Ecology and Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM)

2. Materials and Methods

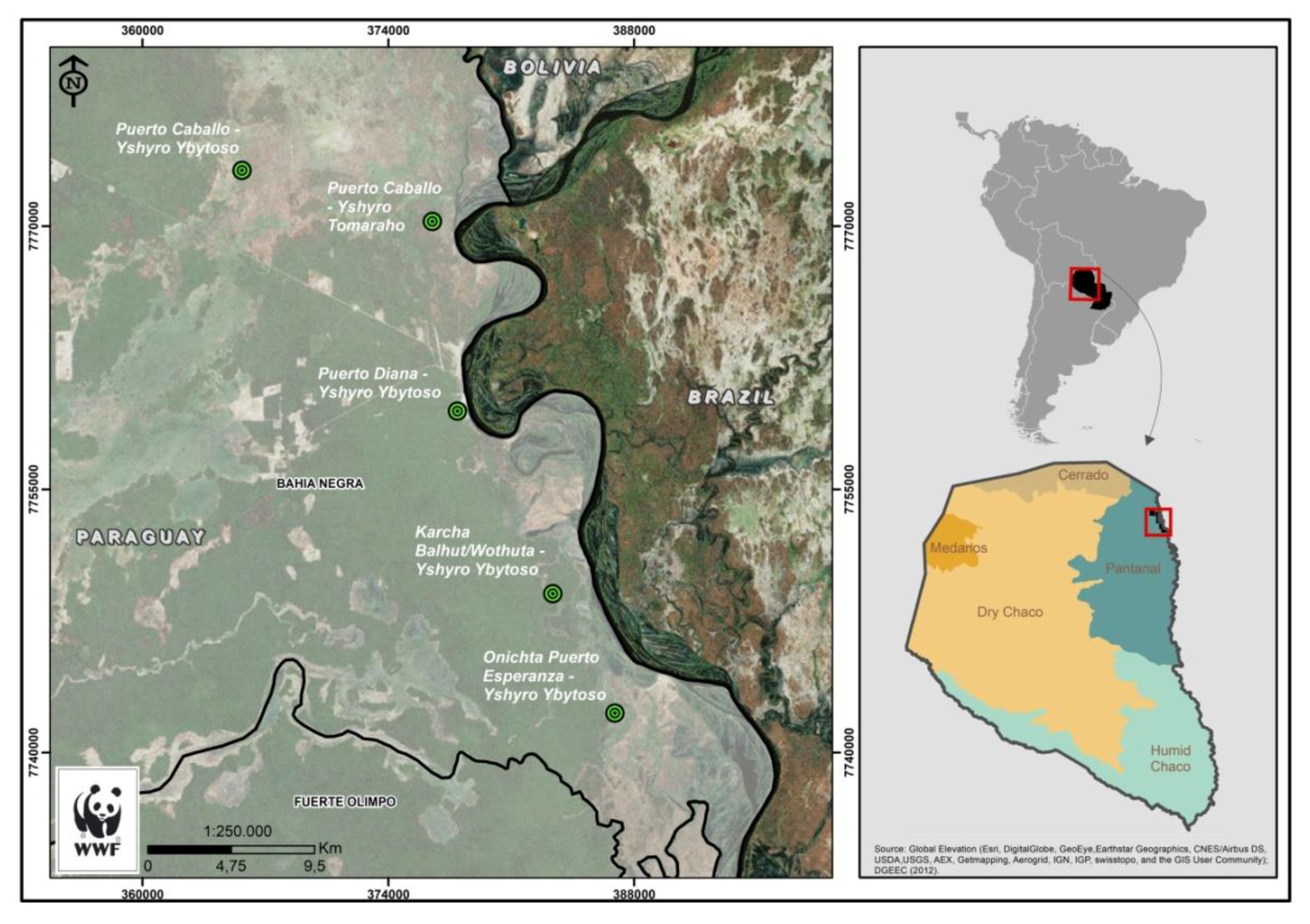

2.1. Case Study Description

2.2. Procedures

3. Results

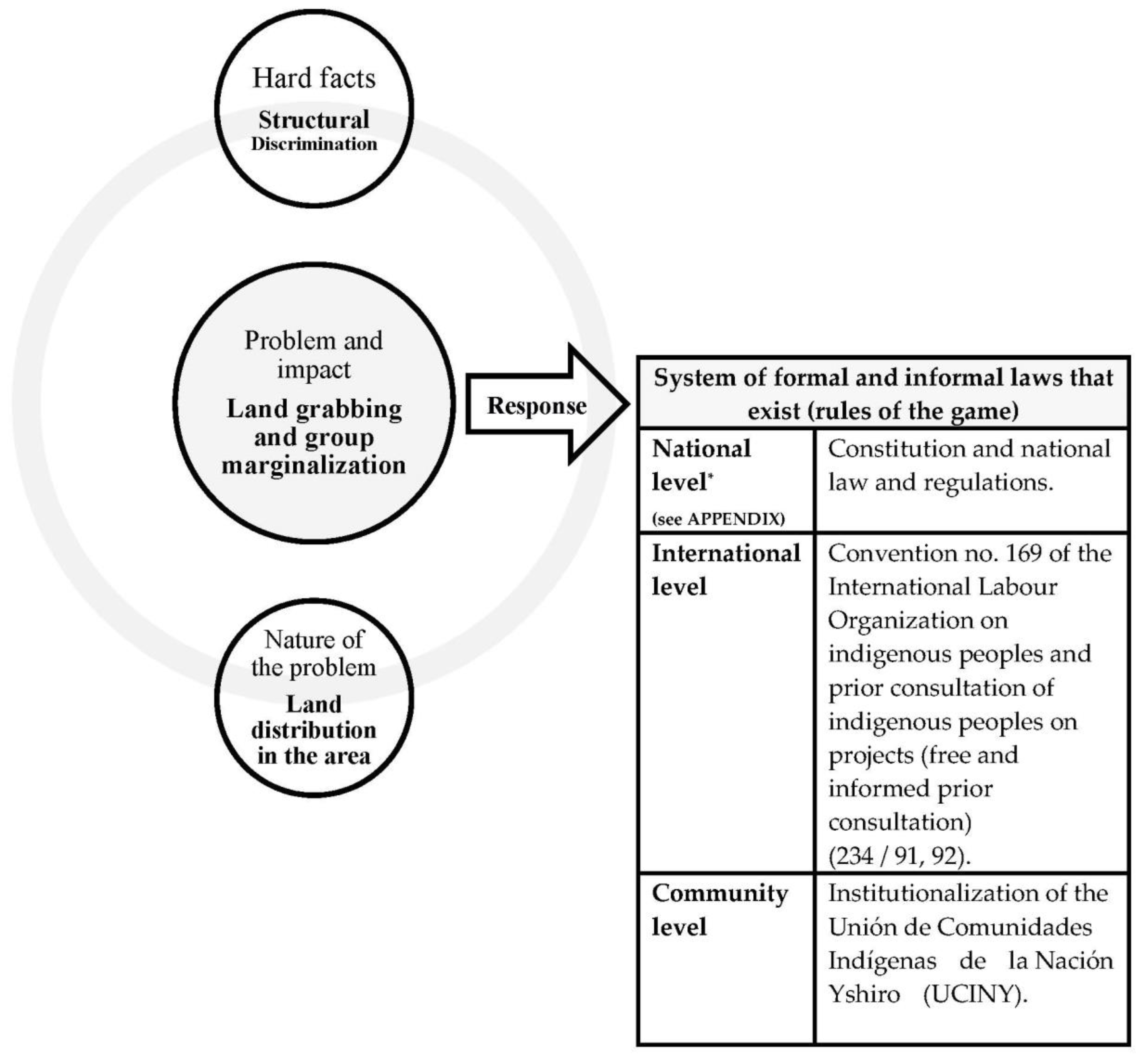

3.1. Problems

3.2. Social Norms

[QCL1] “We (the Yshiro) are like plants, we grow up here, we stay here, and we die here”

[Interpretation] For the Yshiro, the land is the center of the universe, the heart of their culture, and the origin of their identity as a people. As for many other indigenous communities, human and land (or earth) is one unit. It connects the community with their past (as the home of their ancestors), with the present (as a provider of their material needs) and with the future (as the legacy they keep for their children and grandchildren). This is how the Yshiro entail a sense of belonging to a place.

[QCL2] “Our ancestors fought for this land, we need to fight (peacefully) so that our sons and grandsons can stay (and not migrate to the cities).”

[Interpretation] The Yshiro understand their place in the (modern) world as well as their legacy from the past, what they live with today and pass on to future. A perception of vulnerability comes along with the need to maintain those legacies. Conceiving the possibility of development in the modern world implies the inclusion of core values and beliefs (e.g., the concept of reciprocity).

[QCL3] “We shall cross the river on the other side and seek support from other indigenous group from Brazil.”

[Interpretation] Although ancestral territories may be divided by the borders between countries, and by administrative political boundaries, those are fictitious or artificial divisions for the Yshiro. This idea may be seen as a form of indigenous diplomacy, where improving supporting networking with indigenous and non-indigenous communities is perceived as an element of development.

[QCL4] “We use axe and machete to work the land. We need to cultivate and (quite often) go and sell the manioc in the streets of the little town. It is labor intensive (to walk 7 km each way). That’s one of the main reasons people are slowly leaving our indigenous colonies to bigger urban areas (destined to begging, etc.). We need (instead) tractors for the field.”

[Interpretation] The Yshiro understand the impact of marginalization on their labor, thus having an impact on the present and future progress of the community. Alongside the need to strengthen their network, they also understand the need to increase their knowledge of (modern) farm practices in order to improve their economic development.

[QCL5] “The indigenous people cannot only live out of nature (or not anymore). Resources are decreasing with the destruction and depletion of the environment. We need to act and live differently from the past. Our daily hard work on land is merely subsistence. The indigenous should turn from hunters to small producers. We have already started the process but we lack capacity and means.”

[Interpretation] Similar to the interpretation above, the Yshiro need and want to improve their farm practices. This can be seen as a call for support and capacity building from external actors.

[QCL6] “Cattle ranchers and landowners, who are our neighbors, are using tractors, they deforest with chainsaw… They don’t need much human labor. All is mechanized. Cattle ranchers use workforce that comes from other part of the country. They don’t use local workforce.”

[Interpretation] On the one hand, the Yshiro tend to be open to learning and increasing their own productivity, on the other hand, they criticize the lack of labor inclusion in industrialized farming. Once more, this quote shows the openness of the indigenous group to take part in the (modern) local development, although when agriculture and livestock production exclude indigenous labor force, a sense of frustration arises.

[QCL7] “We need to reconstruct our power.”

[Interpretation] To reconstruct the power of the Yshiro means to find new spaces to reaffirm the right to self-determination, as well as to increase their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions.

[QCL8] “We need to fight for our land and territory within a new world (not the one like our ancestors). We shall use a lot of what is offered by the Westernized world; but focus on preserving our (language) and land. We want people and the State to understand that its national constitution talks about a multiethnic and multicultural Paraguay. We are it.”

[Interpretation] Here, the Yshiro advocate for a truly intercultural democracy. The same is based on the complementary exercise and on equal terms of three concepts: direct, participatory, and representative. Alongside the right to self-determination, the Yshiro understanding of democracy implies transforming a condition of exclusion to one of inclusion (e.g., political, economic, etc.).

[QCL9] “Images of indigenous people on publications and reports are good advertising. Not more than that. Real participation and representation of the Yshiro in decision making does not exist. We don’t have any benefit in it even if we are invited to round tables, etc.”

[Interpretation] Once more, community representation includes effective participation in the exercise of decision-making processes. The Yshiro criticize the way in which their image is most commonly used by civil society (e.g., NGOs and development agencies) and by the state. This call to change external approaches to indigenous group shows how imagery representations can foster forms of discrimination (e.g., gender, ethnicity, etc.), resulting in marginalization and exclusion.

[QCL10] “Politics sell the rights of indigenous people.”

[Interpretation] This critique regards the political discourse and propaganda (especially out of election period) that turn the images of the indigenous people into mere ´products´. This idea reinforces the link between political and economic strategies of development (e.g., neo-extractivism), thus causing a negative impact on the community representation of the Yshiro.

[QCL11] “Foreigners come and buy (our) ancestral land.”

[Interpretation] This quote resumes the critique against neo-extractive policies of the state, often forcing indigenous people to leave their ancestral land in order to make way for (foreign) land speculation. Similar to the above, the way in which development is imposed is perceived as a threat to the indigenous land, thus to their identity and survival.

4. Discussion

4.1. Problems

4.2. Social Norms

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| National Level |

| Constitution: |

| Part I |

| Of fundamental declarations, rights, duties and guarantees |

| Title I |

| Of the fundamental declarations |

| Chapter V |

| Of the indigenous peoples |

| Article 62—indigenous peoples and ethnic groups |

| Article 63—of the ethnic identity |

| Article 64—community property |

| Article 65—the right to participation |

| Article 66—education and assistance |

| Article 67—exemption |

| Chapter VII |

| Of education and culture |

| Article 73—the right to education and its purposes |

| Article 77—teaching in maternal language |

| Article 81—of the cultural heritage |

| Article 83—cultural dissemination and tax exemption |

| Part III |

| Of the political ordination of the republic |

| Title I |

| Of the nation and the state |

| Chapter I |

| Of the general declarations |

| Article 140—languages |

| National law and regulations: |

| Law No.904/81: Statute of the Indigenous Communities. |

| Laws 137-143-145 on supremacy of international or regional legal order. |

References

- Fraser, L.H.; Keddy, P.A. The World’s Largest Wetlands: Ecology and Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 21–99. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, E.Y. Gran Pantanal Paraguay; Asociación Guyra Paraguay: Asunción, Paraguay, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Dueñas, D.A.; Mereles, F.; Yanosky, A. Los Humedales de Paraguay; Comité Nacional de Humedales del Paraguay: Asunción, Paraguay, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swarts, F.A. The Pantanal of Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay: Selected Discourses on the World’s Largest Remaining Wetland System; Paragon House: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000; pp. 10–146. [Google Scholar]

- McClain, M.E. The Ecohydrology of South American Rivers and Wetlands; International Association of Hydrological Sciences: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 110–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fachim, E. Safeguarding the Pantanal Wetlands: Threats and Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 714–720. [Google Scholar]

- Junk, W.J.; Brown, M.; Campbell, I.C.; Finlayson, M.; Gopal, B.; Ramberg, L.; Warner, B.G. The comparative biodiversity of seven globally important wetlands: A synthesis. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 68, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eufemia, L.; Bonatti, M.; Sieber, S. Synthesis of Environmental Research Knowledge: The Case of Paraguayan Pantanal Tropical Wetlands. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2018, 7, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, M. Life Projects: Indigenous Peoples’ Agency and Development. In Indigenous Peoples, Life Projects, and Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004; Volume 31, pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hufty, M. Investigating Policy Processess: The Governance Analytical Framework (GAF). In Research for Sustainable Development: Foundations, Experiences, and Perspectives; North-South/Geographica: Bern, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, P. Political Ecology. A Critical Introduction, 2nd ed.; J. Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 39–95. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P. Epilogue: Towards a future for political ecology that works. Geoforum 2008, 39, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Hristov, J. Indigenous Struggles for Land and Culture in Cauca, Colombia. J. Peasant Stud. 2005, 32, 88–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 22–57. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Clark, C.G. Enchantment and Disenchantment: The Role of Community in Natural Resource Conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P.; Brookfield, H.C. Land Degradation and Society; Methuen Books: London, UK, 1987; pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Green, K.E. A Political Ecology of Scaling: Struggles over Power, Land and Authority. Geoforum 2016, 74, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D. Adaptive Capacity and Community-based Natural Resource Management. Environ. Manag. 2005, 35, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.S. Key principles of community-based natural resource management: A synthesis and interpretation of identified effective approaches for managing the commons. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Scoones, I. Environmental Entitlements: Dynamics and Institutions in Community-Based Natural Resource Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1999; pp. 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive Co-management for Building Resilience in Social—Ecological Systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, C.; Schröter, B.; Meyer, A.; Giersch, G.; Meyer, C.; Matzdorf, B. Multilevel Governance in Community-Based Environmental Management: A Case Study Comparison from Latin America. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Estadística, Encuestas y Censos (DGEEC). Paraguay: Proyección de la Población por Sexo y Edad, Según Distrito, 2000-2025; Gobierno del Paraguay: Asunción, Paraguay, January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zanardini, J.; Biedermann, W. Los Indígenas del Paraguay; Editorial Palo Santo: Asunción, Paraguay, 2001; pp. 29–77. [Google Scholar]

- Federación por la Autodeterminación de los Pueblos Indígenas (FAPI). Tierras Indígenas: Compilación de los Datos de Tierras Indígenas en Paraguay; FAPI: Asunción, Paraguay, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, B. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1922; pp. 20–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J.S. Perspectives of Effective and Sustainable Community-Based Natural Resource Management: An Application of Q Methodology to Forest Projects. Conserv. Soc. 2018, 9, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, M. The Threat of the Yrmo: The Political Ontology of a Sustainable Hunting Program. Am. Anthropol. 2009, 111, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.F.; Roy, E.D.; Diemont, S.A.; Ferguson, B.G. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): Ideas, inspiration, and designs for ecological engineering. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alier, J.M.; Jusmet, J.R. Economía Ecológica y Política Ambiental; Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambientea: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2000; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión de Verdad y Justicia (CVJ). Informe Final: Capitulo Conclusiones y Recomendaciones; Gobierno del Paraguay: Asunción. Paraguay, 2008.

- National Research Council. Measuring Racial Discrimination; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Pager, D.; Shepherd, H. The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2008, 34, 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincus, F.L. Discrimination Comes in Many Forms: Individual, Institutional, and Structural. Am. Behav. Sci. 1996, 40, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, F. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1969; pp. 12–100. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, F. Models of Social Organization; Occasional Paper No. 23; Royal Anthropological Institute: London, UK, 1966; pp. 42–72. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, F. Os Grupos Étnicos e suas Fronteiras: Teorias da Etnicidade; Editora da Unesp: São Paulo, Brasil, 1998; pp. 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso de Oliveira, R. Do Índio ao Bugre: O Processo de Assimilação dos Terêna; Francisco Alves: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1976; pp. 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, M.M. Assimilation in American Life; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, I. Ethnicity and National Integration. Cahier d’Etudes Afr. 1960, 1, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 38–98. [Google Scholar]

- Llambí, L. Neo-Extractivismo y Derechos Territoriales en la Orinoquia y Amazonía Venezolana. In Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Rurales; Asociación Latinoamericana de Sociología Rural (ALASRU) and Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones Laborales (CEIL-CONICET): Montevideo, Uruguay, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 126–198. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, A. Extractivismo y neoextractivismo: Dos caras de la misma maldición. Más allá Desarro. 2011, 1, 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gudynas, E. Diez tesis urgentes sobre el nuevo extractivismo. Extr. Política Soc. 2009, 2, 187–225. [Google Scholar]

- Guereña, A. Kuña ha yvy. Desigualdades de Género en el Acceso a la Tierra en Paraguay; ONU Mujeres Paraguay/Oxfam en Paraguay: Asunción, Paraguay, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, M.C. História dos Índios no Brasil; Companhia das Letras, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura; FAPESP: São Paulo, Brasil, 1992; pp. 22–45. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.M. Negros da Terra. Índios e Bandeirantes nas Origens de São Paulo; Cia das Letras: São Paulo, Brasil, 1994; pp. 13–81. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.M. Guia de Fontes para a História Indígena e do Indigenismo em Arquivos Brasileiros; Núcleo de História Indígena e do Indigenismo—Nhii/Usp: São Paulo, Brasil, 1994; pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.M. O Desafio da História Indígena no Brasil. A Temática Indígena na Escola: Novos subsídios para Professores de 1º e 2º Graus; MEC; MARI; UNESCO: Brasília, Brasil, 1995; pp. 11–81. [Google Scholar]

- Guereña, A.; Rojas, V. Yvy Jára. Los Dueños de la Tierra en Paraguay; Oxfam en Paraguay: Asunción, Paraguay, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blaser, M. Storytelling Globalization: From the Chaco and beyond; Duke University Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 28–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nadasdy, P. Hunters and Bureaucrats: Power, Knowledge, and Aboriginal-State Relations in the Southwest Yukon; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2003; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; Sage: London, UK, 1992; pp. 24–69. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 12–33. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. El ‘nuevo’ imperialismo: Acumulación por desposesión. In Socialist Register 2004. El Nuevo Desafío Imperial; Merlin Press; CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W.D. Colonial and Postcolonial Discourses: Cultural Critique or Academic Colonialism? Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 1993, 28, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W.D. Occidentalización, Imperialismo, Globalización: Herencias coloniales y teorías poscoloniales. Rev. Iberoam. 1995, 61, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. Una Epistemología del Sur: La Reinvención del Conocimiento y la Emancipación Social; Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales; Siglo XXI Editores: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R. Law in an Emerging Global Village: A Post-Westphalia Perspective; Transnational Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, E. Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation. Tipití 2004, 2, 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, E. The Inconstancy of the Indian Soul. The Encounter of Catholics and Cannibals in 16th-Century Brazil; Prickly Paradigm Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; pp. 20–68. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Inclusion Matters: The Foundation for Shared Prosperity. New Frontiers of Social Policy; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, M. The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies; Routledge: London, UK, 1922; pp. 10–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bellier, I.; Legros, D. Mondialisation et Stratégies Politiques Autochtones; Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2001; pp. 15–88. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. From industrial society to the risk society: Questions of survival, social structure and ecological enlightenment. In Theory, Culture and Society; Sage: London, UK, 1992; Volume 9, pp. 97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Korovkin, T. Weak weapons, strong weapons? Hidden resistance and political protest in rural Ecuador. J. Peasant Stud. 2000, 27, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. Public Participation and Mobilization |

| 2. Social Capital and Collaborative Partnerships |

| 3. Resources and Equity |

| 4. Communication and Information Dissemination |

| 5. Research and Information Development |

| 6. Devolution and Empowerment Including Establishing Rules and Procedures |

| 7. Public Trust and Legitimacy |

| 8. Monitoring, Feedback, and Accountability |

| 9. Adaptive Leadership and Co-Management |

| 10. Participatory Decision Making |

| 11. Enabling Environment: Optimal Pre or Early Conditions |

| 12. Conflict Resolution and Cooperation |

| 1. Public Participation and Mobilization | (c) |

| 2. Social Capital and Collaborative Partnerships | (b) |

| 3. Resources and Equity | (c) |

| 4. Communication and Information Dissemination | (c) |

| 5. Research and Information Development | (b) |

| 6. Devolution and Empowerment Including Establishing Rules and Procedures | (a) |

| 7. Public Trust and Legitimacy | (c) |

| 8. Monitoring, Feedback, and Accountability | (c) |

| 9. Adaptive Leadership and Co-Management | (a) |

| 10. Participatory Decision Making | (b) |

| 11. Enabling Environment: Optimal Pre or Early Conditions | (a) |

| 12. N/A |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eufemia, L.; Schlindwein, I.; Bonatti, M.; Bayer, S.T.; Sieber, S. Community-Based Governance and Sustainability in the Paraguayan Pantanal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195158

Eufemia L, Schlindwein I, Bonatti M, Bayer ST, Sieber S. Community-Based Governance and Sustainability in the Paraguayan Pantanal. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195158

Chicago/Turabian StyleEufemia, Luca, Izabela Schlindwein, Michelle Bonatti, Sabeth Tara Bayer, and Stefan Sieber. 2019. "Community-Based Governance and Sustainability in the Paraguayan Pantanal" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195158

APA StyleEufemia, L., Schlindwein, I., Bonatti, M., Bayer, S. T., & Sieber, S. (2019). Community-Based Governance and Sustainability in the Paraguayan Pantanal. Sustainability, 11(19), 5158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195158