Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that world leaders committed to fulfilling by the year 2030 include the protection of labor rights and the promotion of a safe and decent workplace under acceptable health and well-being conditions. The private sector has a critical role in achieving these goals. There are many very good practices in modern organizations to prevent and avoid pain and suffering among workers, but there is another challenge that has guided this research: What happens when the suffering has already occurred? The objective of this research is to explore how the private sector organizations in Spain deal with their workers’ suffering. This study used discourse analysis, extracted from eight in-depth interviews with human resources managers, as well as a discussion group of twelve leaders from various national and multinational companies. It has been found that there is a clear awareness of the existence of suffering in their organizations, but there is also a general reluctance to confront it and address it.

1. Introduction

In 2015, world leaders adopted a series of global objectives to eradicate poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all as part of a new sustainable development agenda [1]. Each goal has specific objectives that must be met by 2030 [2]. One of these goals is to attain a situation of decent employment in an environment of sustainable economic growth. A decent job should be one which does not cause suffering amongst employees, although the traditional method of considering human beings as resources at organizations has led to an increase in suffering at work and, therefore, a decrease in the efficacy of the purported profits [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

Similarly, the highly uncertain environment and accelerated technological change are, in many cases, leading to more suffering. It is important to remember what has happened in well-known companies, such as Renault and France Telecom, as an example of how suffering exists in the modern work environment [4].

Currently, as shows Figure 1, large number of psychosocial risks are identified in the workplace; that is, factors from the organization itself, such as its content or the type of tasks that can put workers’ health at risk. Following a study by the World Health Organization [5], the following factors have been identified: The lack of control and bad decisions [6]; imbalances between effort and reward [7]; monotony [8]; poor communication and information [9]; lack of clarity on roles and objectives [10]; and pressure associated with deadlines.

Figure 1.

Sustainable development goals that must be achieved.

To achieve sustainable economic development, societies must create the necessary conditions so that people have access to quality jobs, stimulating the economy without harming the environment. There should also be job opportunities for the entire working age population, with decent working conditions (sustainable development goal (SDG) 8), without the employees becoming ill or suffering.

The objectives of sustainable development, as Pedersen points out [11], are a great gift to help private sector companies to guide their strategic plans. A key part of that strategy should include workers.

In 2011, the Spanish government wanted to drive forward policies based on sustainability in public sector companies. Despite the legislation and its good intentions, practices that actually promote sustainability in Spain are still few and far between [12]. Spanish companies have considered for many years now that reputation and brand image are essential for their future, as well as the economic agents with which they work and sustainability. A study by González and Morales [13] states that there are data that prove that the reputation of a large number of companies is perceived quite negatively.

In the framework of accounting for sustainability, there is a growing tendency to incorporate new disciplinary perspectives that provide light, beyond the databases, in the registration and control of the achievement of the SDGs [14]. Moreover, the last report of the Observatory of SDGs [15] notes that the results observed in the non-financial report are insubstantial and insufficient, considering the magnitude of the challenge posed by the 2030 Agenda. The main challenge will continue to be the improvement of the content and the depth of the memories.

There are academic works that are finding the relationship between institutional factors and the adoption of SDGs in their sustainability reports [16]; in this aspect, there is still a long path to walk in the Spanish environment, as indicated in the report of the aforementioned Observatory.

The Deloitte report from 2016 “2030 Purpose: Good Business and a Better Future” rates the commitment among the main Spanish companies to sustainable development and the sustainable development goals (SDGs), as well as their degree of integration within company strategy and how they run their companies. The conclusions reached are that in Spain, company commitment to the SDGs is still very small, and only nine per cent of the companies on the IBEX 35 have incorporated proposals into their strategies that specifically integrate any of the goals. This finding reveals the opportunities that companies have to strengthen their plans and become more involved with Agenda 2030. Forty per cent of large listed Spanish companies consider the SDGs in their sustainability reports and on their websites, although only 20% measure the contribution they make. There is concern regarding the road that must be taken to attain the SDGs, although the figures prove that there is still a long way to go. If the incredibly positive effect that the fulfilment of these sustainability goals has proven to have for the benefit of humanity and long-term business success is considered, there is a great opportunity to improve and get to work.

Some organizations have realized that best practices on good governance, environmental, and ethical issues provide market value because they matter to investors, who are increasingly concerned about these matters. These efforts are being recognized by indexes like the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI). There were 18 Spanish companies included on this world index in 2016, and 14 on the DJSI Europe. These numbers inspire hope, although it is important to add that close to 85% of the Spanish gross domestic product comes from small and medium enterprises, and that the organizations referred to above are large banks and other companies (Banco Santander, Ferrovial, Telefónica …), as well as the fact that these indexes focus primarily on the financial sector and make reference to economic sustainability.

In 2016, and for the creation of these indexes, the highest scores were obtained in areas related to corporate governance, codes of conduct, and environmental policy. Conversely, one of the lowest scores was assigned to the development of human capital, which is the focus of our study. The field that grew most in 2016 was philanthropy and corporate responsibility, with 22.09% of companies involved being compliant with this area. Conversely, the field that decreased most was human rights and indicators on employment practices, with a drop of 34.82%. This last figure corroborates the conclusions that are seen in this study on the relationship between suffering in the business world and fulfillment of the sustainable development goals.

The private sector plays a critical role in the development of sustainable development goals. Some of their characteristics, such as the ability to respond, innovate, or be able to find efficiencies, make private companies an essential place for implementing policies in order to achieve objectives [17].

This document aims to highlight the existence of an internal factor of unsustainability that questions the sustainability reports of many companies. If the main objective is to improve the sustainability of organizations, it is necessary to introduce indicators of intangible variables that contribute to the better monitoring of corporate governance—in this case, the management of people.

The sustainability reports of the organizations should incorporate these intangible factors, as already indicated by Rosati and Faria in their work [18]; without them, it will be very difficult to take charge of the complexity and depth of the SDGs.

This work aims to provide an analysis of how private sector companies are responsible not only for their own sustainability, but also for global sustainability. This makes it necessary to demonstrate internal practices and policies that lead to the unsustainability of current models of production and consumption [19]. Models that, in many cases, are sustained in the suffering of their workers.

Pain and suffering of people at work is an issue which very few studies have examined from the viewpoint of company management. This in itself is a relevant point, as is the subjectivity that has to be dealt with. Likewise, although the issue is by no means easy to analyze, it should really be considered to be able to transform the reasons that cause it. Suffering exists; it is difficult to see, and it is also a problem. People managers in companies view it as a difficulty that they do not handle or confront, as is shown later. Tackling employees’ suffering also entails an ethical challenge, which can and should contribute to improving the health of society as a whole, all with the intention of people who are affected by situations of mental exhaustion that cause suffering recovering their vitality [20].

This article offers a theoretical argument in order to indicate how the objective of decent work is seriously threatened, as it is precisely that work which generates suffering in people. Subsequently, the method used to extract the information will be addressed, as well as the composition and characterization of the informants. The study concludes with a description of the results of the discourse analysis carried out and the conclusions that lead to a series of recommendations for organizations and their human resources departments.

The objective of this study is to analyze the existence of malaise and suffering in actual companies, and, as a consequence of that suffering, the inability for labor organizations to be sustainable as soon as its human capital is being eroded by the internal suffering.

The purpose, therefore, is to demonstrate that objective # 8 of the United Nations, “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all” is threatened by the very structure of organizations. Likewise, the intimate relationship of some objectives with others makes the suffering generated a direct threat to the third part: “guarantee a healthy life and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

2. Theoretical Framework

Workplace suffering is manifested by several observable symptoms, which include stress, burnout, anxiety, worry, and depression. Burnout leads to a type of exhaustion and fatigue, a feeling of inefficiency and distancing from tasks [21]. Anxiety is an extremely common symptom seen in professional settings. People suffering from anxiety believe there is danger, even if it is unreal and in the future, but they are not capable of preventing it [22]. These negative scenarios lead to complex situations arising in the workplace. This is also when people are more prone to becoming depressed [23]. Mobbing at the workplace is when an employee is hassled by his or her colleagues and/or superiors or belittled and shown lack of respect, which occurs frequently and is ongoing over time [24]. A study revealed that 15% of employees today feel bullied or mobbed [25].

These psychosocial malaises, associated with labor market precariousness, continue to be outside the radar of official statistics. (The Spanish National Statistics Institute collects the number of labor absences, but does not report on their causes.) In Japan, some 60% of employees suffer, or have suffered, stress or anxiety in the workplace [26]. A research team in Sweden has created a model that can predict the length of absence due to stress and mental disorders [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The European Survey on Working Conditions in the European Union is a questionnaire conducted with personal interviews in all member countries that asks about the most varied aspects of working conditions, such as work organization, the length of the workday, relationships between employees at organizations, and healthy working habits. Conducted with employees in the 27 EU member states, a noteworthy finding among the results of the survey is that nearly half of the 22,000 employees surveyed in the different countries experienced physical or mental distress due to their working conditions [28].

Professionals experience times of pressure during which merely the risk of job loss—even just the possibility—makes them feel extremely vulnerable, due to the responsibilities taken on in modern-day society and that condition us to a greater or lesser degree. Faced with this situation, some people protect themselves by exteriorizing a stance of personal toughness, while others may show emotional suffering or discomfort that society judges as a sign of this vulnerability. In either of the two options, human beings perceive the work they must do for the rest of their professional lives as an arduous and costly task, a dead-end street in which they will always be accompanied by some type of suffering [29].

This perception is clearly influenced by the ideological context and structure of organizations today. If suffering, even non-specific, is a concept that refers to an emotion experienced by human beings by the mere fact of being human, with ‘a state of severe stress associated with events that threaten a person’s integrity’ [30] (p. 639), this cannot be removed from their presence in whatever job they hold, and even more so if the setting of this study is as frequented by professionals as their workplace [31].

A study conducted by Van Woerkom and Meyers [32] showed that the perception workers have of the organizational climate contributes to better professional results or makes them difficult, as well as whether workers have a proactive or reactive feeling. According to Shuler and MacMillan [33], if there is suffering and it is not managed effectively, higher profits will not be achieved and the desired economic sustainability will be harder to reach. There are those who state that the so-called technological revolution is likely to create social tensions in which employees, immersed in the age of knowledge, displace others, marginalizing them and making them unemployed [34]. Marcie LePine and others [35] published an article analyzing the influence of charismatic leaders on stress among their teams and how both can affect work performance. The charismatic leader can lessen the suffering of his or her employees or, conversely, foster it if his or her decisions produce situations of excessive stress. Bontemps [36] claims that workplace suffering involves human, social, and economic costs.

All of these statements could, logically, make it harder to achieve the objective of social and economic sustainability that is analyzed herein. And that is why, as acknowledged by human resources directors, it cannot be confirmed that current people management models include a reference to people’s suffering at business organizations and, therefore, how to prevent it. Many current working methods put the mental, physical, and social health of a large number of people at risk. Employees’ mental health continues to be a field that is practically ignored. Some years ago, several authors, like Christophe Dejours [37], qualified employees’ situation at that time as an existential drama that had an impact on their mental and physical health. Thus, a conflict occurred between individuals’ personal initiatives and the work organization and, therefore, suffering that became more painful the more that people were hiding it. In the modern day, Harrington and Rayner [38] have introduced another factor that directly points to those responsible for people management and the trust they are given by employees with regard to the treatment given to workplace suffering.

As Tom Kochan, co-director of the MIT Institute for Work and Employment Research, states, the ongoing lack of decent working opportunities, insufficient investment, and low consumption erode the basic social contract and everybody has the right to share in progress. The creation of quality jobs continues to represent a large challenge in almost all economies. Individual contracts must be created that provide decent work and quality jobs in which this proper share in progress belongs to everyone. It is not just about jobs with fair remuneration that favor productivity, but also personal growth. To achieve sustainable economic development, societies must create the necessary conditions so that people have access to quality jobs that protect and support people from the multiple factors that can threaten employees’ health. Point eight of Sustainable Development Goal Eight establishes that we must:

8.8. Protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment (it is understood that precariousness often leads to distress).

Sustainable Development Goal 3 states that we must ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for everyone at all ages, and its Sub-Section 3d: Strengthen the capacity of all countries, especially developing countries, on early warning, reduction of risks and management of national and global health risks.

Workplaces are environments in which people live and suffer and should also be, and in many cases are, environments in which they ensure risk management and reduction (SDG 3), although there is still a long road ahead so that they are employed as early warning or ensuring and promoting well-being, as also set out in this goal. The tools requested by company managers (as will be shown) to alleviate or reduce suffering could refer to this ‘risk reduction and risk management’ sought by SDG 3.

It is incompatible to speak of the economic and social sustainability required by the sustainable development goals insofar as suffering and discomfort occurs at companies, impacting productivity and, thus, threatening economic progress and regrettably affecting workers’ health as well.

3. Method and Sample

In this study, the degree of dedication of those in charge of people management is analyzed. This helps to verify whether they are complying with the sustainable development goals drafted by the UN on this issue and that must be achieved by 2030.

The study also analyzes whether the existence of suffering in the professional world means that current employment conditions are fair and decent (SDG 8) and if they put workers’ health and well-being at risk (SDG 3). As may seem logical, both objectives are closely related and their evaluation will have to take place simultaneously [39].

To do so, it is important to be aware that the factor being studied—suffering—has a highly subjective component, which takes place in a daily setting from which it cannot be separated. This means that some variables cannot be controlled, both due to ethical and practical reasons, which therefore forces the use of more hermeneutic and interpretive data collection techniques. Hence, the methodology employed in this work is qualitative. This methodology was selected because it gives priority to sensitivity, in partial detriment to objectivity. It should be stated that the concept of ‘sensitivity’ must be interpreted here according to the definition provided by Juliet Corbin and Anselm Strauss [40] that refers to researchers’ skill and competence to understand the environment being analyzed from their privileged position and using their knowledge as an analysis tool.

Of the different qualitative research methods in use, in-depth interviews have been deemed the most suitable for collecting opinions on suffering from managers involved in people management. These personal interviews represent an extremely useful method due to the quantity and quality of the information they can obtain. As confirmed by several papers on methodology, in-depth interviews are highly suitable for the exploratory phases of studies [41]. Other phases frequently use studies directly or indirectly related to people’s behavior at organizations. The in-depth interview is a commonly used qualitative research method, which consists of a private, professional, and structured conversation with different previously-selected people, with the aim of conducting an analytical study of the responses obtained, in order to establish a diagnosis that is as correct as possible for a specific problem [42].

Prior to this, and with an exploratory nature, the research team participated as observers in a discussion group that brought together diverse people management leaders from some of the main Spanish national and multinational companies. None of these directors were subsequently interviewed. The range of companies whose managers were emailed was determined by the prior information available on their good practices for the issue in question.

The group was formed of twelve managers, eight women and four men, from the technological, large consulting, electrical, insurance, energy, and education sectors.

The discussion was focused on the responsibility of the organization for the welfare of its workers and towards the concept of a ‘healthy company’. The research team’s objective was to see how a group of experts and human resources managers addressed the suffering of their workers to define the keywords and the universe of meanings that were related to that suffering.

All of them were informed that the research was exploratory. After selection, the discussion was recorded and confidential; no participants are identified and the purpose is strictly academic.

This experience also confirmed to the research group that this method of gathering information was not the most suitable for the stated objective. Suffering, as seen time and time again, is a topic which creates emotions such as embarrassment, both among the protagonists as well as the witnesses, and only comes to light in a suitable open and warm environment. Finding this open environment amongst people who are meeting for the first time in a strange place and being observed proved too difficult for the team.

On the other hand, the simple act of gathering three professionals, with senior positions, in the same place also proved to be an impossible task in many cases. Nevertheless, the text that was obtained from this group formed part of the body of text for the project contents. These difficulties meant that the researchers chose in-depth interviews as the main way of obtaining information.

As previously mentioned, the discussion group was primarily used to see which keywords were commonly used to talk about the lack of wellbeing in organizations. Based on this initial keyword analysis, 52 questions were created and these formed part of the in-depth interview.

This list of questions was sent to fifty people management or business ethics experts, university professors, and business leaders. They were all asked to judge the suitability of the questions and classify them as excellent, suitable, unsuitable, or poor. The design of the study and its objectives was explained to them in detail beforehand.

Twelve of these judges made general comments regarding the project and how information could be obtained from human resources managers.

Based on this work, the discussion guide was created, as well as a series of recommendations which helped to see some of the characteristics of the subject being researched.

It is worth dwelling on these four recommendations from the twelve judges, as these are revisited in the results of the content analysis.

- Do not ask directly about suffering.This recommendation highlights a topic which evokes negative emotions or embarrassment—there is resistance to confront pain or those who suffer from pain. Approaching this in the wrong way could cause the respondents to put their guard up.

- Interviews should not be rushed and enough discussion time should be allocated.Suffering is a topic for which it is necessary to create a certain climate of trust and this requires time.

- Care should be taken not to see the interviewer as a victim or as the perpetrator.This recommendation shows the fear of social stigma associated with suffering.

- As much objective information as possible should be gathered.The judges highlighted the need to find objective indicators that can form a strong foundation to work from. It will be shown, subsequently, how these recommendations emphasize factors which are very closely linked to the results discovered in the content analysis.

Thanks to this evaluation of the questions, a five-part discussion guide was created: Introduction, information on the company, data on sick leave and staff turnover and its causes, management of this situation, and future evolution. The aim was always to establish a friendly interview environment without trying to establish who was to blame. Questions which had been classified as unsuitable or poor were never asked.

As mentioned, two actions were carried out with people management directors: (1) A discussion group, and (2) in-depth interviews. The decision that it would be these people managers who helped with this part of the work was made for these reasons:

- Human resources directors are in charge of detecting, alleviating, and, where applicable, managing suffering at companies.

- Human resources directors work very closely with workers and they, themselves, are also employees, so their opinions can be obtained on two different fronts.

- They are also aware, as will be shown, to what degree their policies and practices are implemented and followed in the daily work setting, and how far reaching they could be in other circumstances.

The people selected to be interviewed were a group of human resources directors that were believed to be sufficiently representative due to their ages, genders, career advancement, and years at company, as well as the origins and sizes of their companies.

Human resources managers from different business sectors, and companies of very different sizes, were sought. The participants had extensive experience in the area of people management and, obviously, both women and men were represented. Table 1 shows the characteristics of this sample described.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the human resources directors interviewed.

Based on the interview script resulting from the advice received from the aforementioned experts, the people interviewed were asked for information regarding the focus of this study. Their opinions were completely recorded on audio and notes were taken in situ. A further request was that their answers included concrete cases of experiences and not just opinions.

The sample size was determined by the saturation of content that was obtained by analyzing the responses that were received from the people interviewed [43]. Once in possession of the text for the first interview, the corresponding analysis of keywords and semantic links was carried out.

The analysis of the second interview was added to the first one, in order to validate that almost 50% of the terms used by both were the same, albeit with a different priority order. Subsequently, the following ones were added to the first two interviews, in order to carry out the corresponding analysis.

When further interviews were included, the similarities between keywords were added to.

This research team was checking how it was increasingly difficult to find new semantic content in the interviews, and this was corroborated with their corresponding keyword analysis. By adding the eighth interview to the previous seven, it was found that there was a 97% agreement of terms and that the priority order was the same. The estimate of the likelihood of new content appearing was much less than the cost of continuing to conduct interviews.

Eight participants were sufficient, as shown by the abundance of content and information found in other qualitative studies with similar or fewer samples [44,45,46].

It was established that responses tended to be repeated among the interviews analyzed. Statements from both men and of women were similar, and there was no difference between those with fewer or more years in the job post, those who had resided in other locations, or those working at large companies or smaller ones, regardless of the sector in which they performed their job functions.

Once the dialogue was obtained (from the interviews, as well as the discussion group), the necessary content analysis was carried out using NVivo 11 Pro software.

A decision was made to use a selection of keywords, based on this selection, to see which types of semantic relationships and structures could be found in the text and which of these were most frequent.

This process can be structured in 4 phases:

First phase: Selection of keywords. These words provide a concise and precise summary of a document. The idea was to select words from a text which can give a complete view of its content [47]. There was a focus both on the frequency of use, as well as the relative position in which they appear [48].

The selection of keywords was limited to nouns and verbs and this resulted in 29 keywords.

16 keywords relating to ‘suffering’.

6 keywords relating to ‘problem’.

5 keywords relating to ‘managers’.

2 keywords relating to ‘tools’.

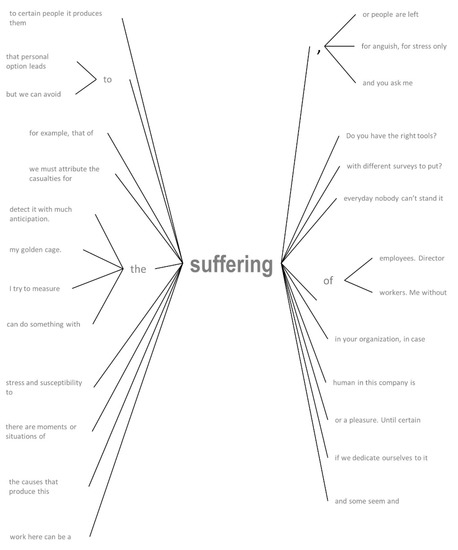

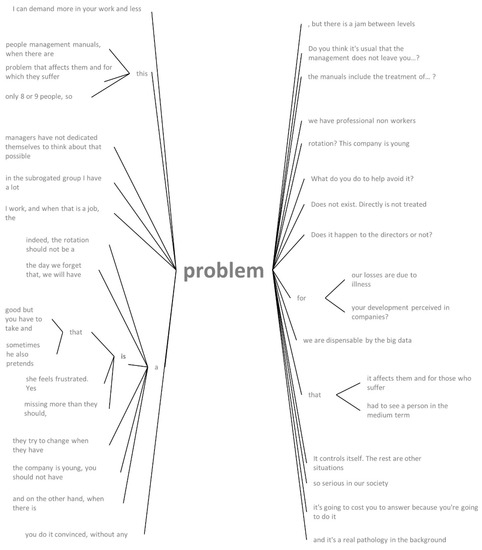

Second phase: Creation of keyword relationship diagrams. Each of these keywords was linked to others in a grammatical sense. Diagrams were created for each of the 29 keywords. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the semantic links between the words ‘suffering’ and ‘problem’. This configuration of related ideas forms the basis for starting the analysis of the ideas which appear in the dialogue that was obtained.

Figure 2.

Relationship diagram for the term ‘suffering’.

Figure 3.

Relationship diagram for the term ‘problem’.

Third phase: Differentiation of grammatical meaning. It should be determined whether the meaning of each phrase is positive (there is suffering, there are problems, management make decisions) or whether they were negative sentences (there is no suffering, there are no problems, management do not make decisions).

This differentiation made it possible to start seeing a series of homogenous discourse amongst the participants, in such a way that only two phrases were found in which ‘suffering’ had a negative meaning. In contrast, only one was found with a positive meaning with regards to directors and managers.

Fourth phase: Looking for redundant discourse and interpretation. Based on the diagrams and separation of meanings, the process of finding common ideas and repetitions started to actively seek contradictions and exceptions in the common discourse. As a result of this analysis, the four statements discussed in the following part of the study emerged.

4. Results

The statements from the people interviewed were subsequently interpreted, with regard to the focus of this study. As mentioned, the most frequent terms and concerns were used, and the conclusions that emerged from the discussions were also read and interpreted iteratively.

As a result of the analysis performed, the following conclusions can be drawn from the human resources directors interviewed:

Research Proposition 1.

Those responsible for people management state that there are people who suffer in their jobs.

To draw this conclusion, any phrases dealing with the suffering of people at organizations were extracted from the texts of the transcribed interviews. These texts were read, and the meaning of the statements relating to the term being studied was analyzed, as well as other synonyms, their possible causes, and observable symptoms. The term that is the objective of our study (suffering, distress, affliction), or surrounding terms, appeared 57 times throughout the interviews conducted.

It was then investigated whether the people interviewed used the semantic field that gives positive or negative meaning to the hypothesis. In other words, an analysis was carried out on whether or not they were claiming that people suffer or, conversely, that they do not suffer. In only two of the cited 57 occasions in which the interpreted terms were used, was a negative regard used to refer to the fact that directors and younger people, in the opinion of an interviewee, suffer. In all other cases, those responsible for people management did indeed state that there are people who suffer in their jobs.

Research Proposition 2.

It is clear that there is suffering, but it is difficult to see.

In this point, it was considered whether human resources directors are doing anything to prevent, manage, or try to alleviate the suffering they acknowledge exists. They then stated that they would do more if they knew who it was happening to, but also said that what tends to happen is that people suffer in silence or do not dare to report what is happening to them. Indeed, in one more in-depth conversation, the person acknowledged that it is possible that some of his or her employees suffer. Furthermore, those involved in people management take refuge under the compulsory respect for privacy to not enquire into possible cases of suffering. One of the reasons that interviewees pointed out to justify their employees’ silence is the fear of ‘what would they say?’ due to it being an embarrassing or shameful situation. They generally do not admit visiting the psychologist, they state.

The interviewees also acknowledge that if someone is suffering, they perform worse and this will affect company profitability. The human resources directors who were interviewed were aware that their functions must include that of giving their employees hope and expectations. They believe that they should be the ones who provide the tools required so that employees’ professional development makes sense. They stated that it is common at offices for some people to not want to participate in group projects and avoid taking on responsibilities.

People who remain silent are largely those people who do not expect or hope to improve or develop further, in the judgement of those interviewed. Thus, a vicious cycle is produced, so that the individual suffering does not believe his or her future will be better, and this situation in turn reinforces the suffering. Sometimes, the excessive eagerness to try to reach a position that is unattainable to them makes them hide their suffering, which makes it difficult to detect. Some people remain quiet when they are having a rough time because, upon expressing or showing their limitations, this could interfere with their personal ambitions.

Another of the causes that human resources directors cited for people not speaking of their suffering is that of the daily and very frequent quarrels and bickering among staff. They believe that it is their mission to try to prevent this situation in order to thus help workers.

Once again, those involved in people management acknowledged that they should take on responsibilities for matters that could cause suffering and distress. What they do not do is handle the end result, but instead the causes that lead to it. In other words, they do not take responsibility for the outcome of their work, but instead for the possible causes, without paying attention to the result. Human resources directors consider their mission fulfilled when they take action to improve their employees’ lives, regardless of the actual outcome.

Research Proposition 3.

Suffering exists and it is difficult to detect and, further, the problem is not confronted due to fear of making negative reports to their superiors.

They claim that it is never simple to deal with the problem. They recognize a complex reality in which human beings do not have it easy. The interviewees tried to make the team understand that handling the issue directly could entail problems for their jobs. Employing the same method as for the semantic field for suffering, the process was repeated for this point with the expressions referring to a problem. These expressions were used 45 times by the interviewees.

Next, an analysis was carried out to establish if they were used in a positive or negative regard. In other words, whether the people managers confirmed the existence of a problem or, conversely, stated that there was no problem. Only one instance was found of a negative sense, which confirms that they did refer to the existence of a problem.

One important claim to bear in mind, as stated by the interviewees, is that they do not deal with the issue of suffering because it has never been done, and they would be the first and only ones, which could be a problem for them. Their words can be interpreted as saying that there is no custom of handling such an important issue, but if there were they would assume responsibility as an essential part of their work because they could also infer its cause. Despite the fact that they stated that they do not handle suffering, present-day people managers acknowledged that suffering is an avoidable problem and that, if they were to handle it, it would improve the situation at companies.

If people’s suffering was confronted, they would try to put the focus on the actual people suffering and not so much on the projects that could appear healthier from the company’s viewpoint. It is about promoting a change in the way of understanding and, therefore, handling a real problem. If suffering does exist at companies, it will have to be handled either sooner or later by human resources directors and, they themselves stated that they are aware that this would be their responsibility.

Research Proposition 4.

Although they wouldn’t like it, it would have to be handled and tools are required in order to do so.

Despite the fact that they stated that they do not deal with suffering, present-day people managers acknowledged that suffering is an avoidable problem and that, if they were to handle it, it would improve the situation at companies. This last statement provides a clue about a reflection repeatedly expressed by the interviewees. They stated that if they had the management tools required, they would possibly dare to confront the problem of suffering at their companies. They referred to this need no less than 36 times. Some also stated that they are given tools when they ask for them, but only one of them claimed to have the intention of using them to this end.

As stated, in this case, not all the assertions are in a negative regard. Not all the interviewees stated that they do not have tools, but instead that they could have them if they asked for them. To be able to justify that they would dare to deal with employee suffering, this cannot be based on mere conjectures in the opinion of those interviewed, but the data must also accompany the statements and support an actual commitment to confronting the problem of suffering at companies. That is why people managers say that they need more tools than those they have today.

The reflection made by these directors was unanimous about the partial, and merely intuitive, knowledge they have that suffering exists at their companies. They also alluded to the need of knowing the reasons why people are suffering, and who is suffering, in order to successfully handle the problem. When they expressed the generalized need for analysis tools, what they really wanted to say is that employees are simply not studied today, either in individual detail or as a group. If what is wanted is not so much to reveal an actuality, but instead to transform what is happening, tools are needed to do so.

In this regard, the analysis shows how the person is seemingly viewed as the center of concern and focus of attention for the professionals who took part in the study. As shown, they acknowledged that they do not handle or concern themselves with this suffering, although they nonetheless stated that people are the priority and that, if they had the necessary tools, they would devote the time the problem deserves to handling suffering at organizations. This is therefore a challenge: Suffering is a challenge for them.

Research Proposition 5.

Suffering is a challenge for them and also for senior management.

This criticism of reality, more or less concealed depending on the case, has been directed at companies’ most senior directors time and again throughout the process of interpreting the interviews that have been conducted. So the task once again was to try to analyze the number of times that terms appear that are related to senior management and to interpret their meaning. References to hierarchical superiors to human resources directors appeared 81 times.

The interviewees assumed that their superiors would not be amenable to implementing policies aimed directly at diagnosing and alleviating, as applicable, the suffering of employees. This is another one of the arguments they provided to avoid decidedly confronting the issue. It is worth considering whether this statement—coinciding among many of the interviewees—is an opinion or a common defensive rationalization. In short, this is an opinion that, while it could be considered a limitation of our methodological approach, nonetheless represents its true raison d’être from a rational viewpoint.

However, they also stated that, if the importance of handling it to improve well-being and, consequently, company profitability were explained, they would attend to the proposals and would give them the support necessary. In short, it is about reasoning with them about the advantages of handling the suffering of workers.

According to the people interviewed, senior managers believed that people doing their jobs satisfactorily in a suitable setting have no reason to suffer. Further, they thought that idleness, a poor work climate contributing to badly executed work and in performing their functions could cause unsought suffering, albeit blameworthy, in some people. If someone is having a rough time at the company, it can be used as a stimulus if it is for a ‘healthy’ reason, or as an example for learning, if it is due to reasons caused by misdirected goals. This is how human resources directors expressed it, to claim that steering committees should take responsibility for employees in any situation, without being unduly hasty.

In the opinion of those interviewed, companies’ steering committee members believe that they do indeed understand and know about everything related to the organization. These senior managers who run organizations stated that all employees should trust in their criteria. They admitted little criticism, which makes them believe that everyone else should trust and heed them, full stop. However, people managers also recognized that for organizations to run well, clearly established leadership is necessary. In their opinions, this leadership must pursue the common good. This statement, however, does not distinguish between the common good, the good of the majority, and personal good.

If suffering was widespread, it would make sense for them to handle it, but if it is not, the satisfaction of the majority is what should be sought. People managers generally acknowledged their organization’s concern for the common good and helping those who need it. Interviewees stated that if it were explained solidly to senior management that there are people suffering, they would attend to the needs of their staff.

5. Discussion

The reality described by current human resources directors at organizations is worrying, and passive attitudes will not change it, but instead the opposite will occur. Due to everything set out above, based on the interpretation of the interviews conducted, it can be stated that:

- Those in charge of people management state that there are people who suffer in their jobs.

- They believe that suffering at companies is a problem that is not being handled.

- Although they would not like it, it should be handled and they would need tools to do so.

- It is a challenge for everyone, including senior management.

Therefore, people managers should not avoid facing the problem, although it is also true, as we have shown, that they have not considered it until now. This fact leads to the preliminary conclusion that current business organizations have the pending task of complying with several of the sustainable development goals for 2030. Concretely, goal three: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”, and goal eight: “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”.

Three fundamental axes are proposed, on which to sustain the policies and practices of human resources aiming to address the suffering in their organizations, and to generate a company focused on people and their welfare.

a—Increase workers’ knowledge.

Two types of knowledge are distinguished: Self-knowledge and the knowledge related to the task and function (meaning and autonomy).

Work activity is one of the most important tasks that any individual faces. There are plenty of opportunities for personal growth and development. Studies on psychological empowerment and its direct relationship with commitment and motivation [49,50] exemplify how work can be done in a workplace in which workers gain security and self-confidence. Likewise, the studies that have been done on psychological flexibility [51] and its relationship with the permeability to new learning and propensity to innovation are very promising.

On the other hand, practices such as mindfulness [52], as well as the experience used [53], are increasingly common in the company, both aimed at improving personal adjustment to the demands of work.

b—Mechanisms of individualized analysis.

Understanding workers is one of the most important and most difficult tasks facing any human resources department. Indeed, it is extremely difficult in large organizations. The aforementioned employee experience is also aimed at improved individualized analysis, as well as the endless satisfaction surveys, commitment, 360° evaluation that are usually carried out in organizations. The analysis of all this data is a complex and large-scale piece of work. It is necessary to provide companies with better technical tools and data analysis to facilitate these analyzes. On the other hand, personal contact will never be replaced by data and metrics. In this sense, new initiatives are observed, such as Chief Happiness Officers [54], that can facilitate that individualized knowledge.

c—Support protocols.

The creation of protocols for suffering situations is a fundamental step to make this type of problem more visible and less embarrassing; but above all, to prevent suffering from worsening and becoming chronic.

In the same way that it is increasingly common for organizations to have protocols to deal with different types of crises, protocols for these eventual crises must be designed. These protocols should be promoted by senior management and be part of the internal marketing plan.

6. Conclusions

This article reinforces the fact that the existence of malaise and suffering in Spanish companies today breaches several of the sustainable development goals with the 2030 agenda, as they are the third objective: “Guarantee a healthy life and promote universal well-being” and the eighth objective: “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.” Moreover, this work tries to contribute a new perspective that contributes to the governance of the sustainability in the companies, and that guides the creation of policies and practices of intervention for the support and treatment of the workers who suffer in the companies.

The sustainability and social responsibility policies of companies tend to focus their objectives on the environment and on external stakeholders. This research shows that there is a large field of action, little explored so far (diagnosis, coping, support for intervention …) focused on the company’s own workers’ well-being. Without this, sustainability is in danger.

There is an astonishing reality: The discovery of a gap, a significant theoretical and practical limitation in the discipline of human resources—or people management—at organizations. This article concludes that this gap does exist and must be rectified to benefit people.

As a result of the qualitative data collection process that was carried out, it is clear that human resources directors acknowledge that suffering is a latent fact at organizations. They state that there are people suffering and who do so silently. They also confirm that handling people’s suffering at their organizations would represent a problem for them. They fear that, if they were to handle the matter, it could bring suffering at their companies too much into the spotlight, which could clarify the prevailing injustice surrounding suffering at organizations.

In all cases they acknowledge that they should handle the problem of suffering at their companies, although they are not doing so. They allude, quite defensively, to the fact that if they were to handle suffering, they would not have sufficient management tools to collect information and suitably individualize it. The human resources directors also allude quite critically, albeit subtly, to their superiors, stating that if they were convinced of the need to handle the problem of suffering at their companies, the way would largely be paved for them to do so. Whatever the reasons, those in charge of people management recognize that suffering exists among their employees and do not do anything to detect it, manage it, and/or prevent it.

Due to their nature and need to be defended, people suffering will try to do so in silence, so it must be the companies—via their human resources departments—that must take charge of the causes that lead to distress and suffering, if they exist, and figure out how to alleviate and prevent them, as applicable. It is highlighted that people managers acknowledge that people suffering do so in silence, which makes it complicated to detect these cases. Awareness of people suffering for professional reasons is usually merely through intuition. However, detection could be more effective if suitable methods for listening to employees’ needs and requirements were institutionalized [55].

This study contributes to the academic debate by showing the resistance to considering and tackling the problem of workers’ suffering. The human resources directors’ discourse shows that, although there are good intentions, there are no policies or processes that can be put in place if their employees raise complaints or show symptoms or behavior suggesting that they are suffering.

The objectives of sustainable development provide an opportunity for the private sector to focus on this reality facing Spanish companies. This reality is unavoidable, given that all sustainability policies should start with a review of what is happening within the organizations.

It cannot be said that companies today watch over the detection, management, and/or prevention of their employees’ suffering or the associated personal suffering. The problem is not being tackled directly, anonymously, on an individual basis, voluntarily and with guarantees, in order to fulfil sustainable development goals three and eight. What can be observed though, is the growing interest in putting employees at the center of company management, which leads to practices like performance assessments. This could be one road towards achieving the aforementioned required knowledge about the person in question.

The conclusion obtained with regard to economic and social sustainability in Spanish companies’ intentions and strategies is that there is still much to do, and this must be seen as an opportunity for growth and economic and social well-being. Along the road to travel, important progress must be made to alleviate the distress and suffering experienced by people in their jobs on a daily basis, which would lead us towards the progressive fulfilment of goals three and eight by the year 2030.

The concept of suffering is so non-specific that many more disciplinary approaches and different methodological perspectives will be required in future research projects. Companies need to be equipped with tools that can minimize, if not eliminate, suffering. It is urgent and necessary to work in favor of economic and social sustainability to, thus, contribute to achieving sustainable development goals three and eight with regard to this study. The future has already started to come into play in the here and now, and it is the outcome of the decisions and actions that are being carried out, which is why it is so important to care for the present [56].

The unspecific nature of the concept of suffering means different approaches will be required in the future, using different methodologies. This aspect should be taken into account in future research projects. Similarly, it would be useful to increase the sample size of companies included in the study and broaden the geographic reach and industrial sectors, so that more generalizable results can be discussed.

The cause or effect of suffering within the companies analyzed has not been studied, although it can be difficult to find objective data of this nature (due to rules around the protection of employees’ data). One of the strengths of this article is that it links the concepts of discomfort and suffering in the Spanish companies analyzed, to the sustainable development objectives. It is important to remember that these objectives are also applicable to private sector organizations in developed countries. This study has also shown, using discourse analysis, that there really is discomfort and pain within the companies analyzed. It would be useful to check in future studies whether there is any activity taking place in companies (either in Spain or elsewhere) whereby the employees are managing their own suffering and proposing support tools so that employees do not feel alone and are able to admit their situation.

Author Contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to the conception or design of this work, and to the analysis and interpretation of data, and has approved the submitted version. They all agree to be personally accountable for their own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature. Conceptualization: G.E., L.J., and F.L.J.; methodology: G.E. and L.J.; interview process: G.E.; data curation: G.L. and F.L.J.; writing: G.E.; and project administration: G.L.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grainger-Brown, J.; Malekpour, S. Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: A Review of Strategic Tools and Frameworks Available to Organisations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colglazier, W. Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science 2015, 349, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudelot, C.; Michael, G. Trabajar Para Ser Feliz? La Felicidady El Trabajo En Francia; Miño y Dávila: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/suicides-renault-france-telecom-workplace-health (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Well-Being at the Workplace Protection and Inclusion in Challenging Times; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Fuhrer, R.; Shipley, M.J.; Marmot, M.G. Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: Prospective results from the Whitehall II Study. Occup. Environ. Med. 1999, 56, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Starke, D.; Chandola, T.; Godin, I.; Marmot, M.; Niedhammer, I.; Peter, R. The measurement of effort–reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suadicani, P.; Hein, H.O.; Gynetelberg, F. Are social inequalities as associated with the risk of ischaemic heart disease as result of psychosocial working conditions? Atherosclerosis 1993, 101, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, D.M.; Wolf, G.D. An integrated approach to reducing stress injuries. In Stress and Wellbeing at Work: Assessments and Interventions for Occupational Mental Health; Quick, J.C., Murphy, L.R., Hurrell, J.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, G.L.; Cook, J.A.; Fogel, S.; Applegate, M.; Frank, B. The effect of patient- focused redesign on midlevel nurse managers role responsibilities and work environment. J. Nurs. Adm. 1999, 29, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, C.S. The UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) are a great gift to business. Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrinaga, C.; Luque-Vilchez, M.; Fernández, R. Sustainability accounting regulation in Spanish public sector organizations. Public Money Manag. 2018, 38, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, G.M.; Vega, M.E. Corporate reputation and firms performance: Evidence from Spain. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1231–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: an enabling role for accounting research. Acc. Audit. Acc. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiñeira, A. La Caixa Foundation, Cátedra de Liderazgos y Gobernanza Democrática. In Proceedings of the La Necesidad de Acelerar la Implantación de la Agenda 2030, ESADE Barcelona, Spain, 29 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Business contribution to the Sustainable Development Agenda: Organizational factors related to early adoption of SDGs reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrinaga, C.; Moneva, J.M.; Ortas, E. Veinticinco años de Contabilidad Social y Medioambiental en España: Pasado, presente y futuro (Twenty-Five Years of Social and Environmental Accounting in Spain: Past, Present and Future). Span. J. Financ. Acc. (Forthcom.) 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligmann-Silva, E. Trabajo y Desgaste Mental. El Derecho a Ser Dueño De Sí Mismo; Octaedro: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. Comprendiendo el Burnout. Cienc. Y Trab. 2009, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sandín, B. Factores de predisposición en lso trastornos de ansiedad. Rev. Psicol. Gen. Apl. 1990, 43, 343–351. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Harris, T. Social Origins of Depression; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C. Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glambek, M.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Hetland, J.; Einarsen, S. Workplace bullying as an antecedent to job insecurity and intention to leave: A 6 month prospective study. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2014, 24, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; Haruyama, Y.; Mitsui, K.; Muto, G.; Nishiura, C.; Kuwahara, K.; Wada, H.; Tanigawa, T. Durations of first and second periods of depression induced sick leave among Japanese employees: The Japan sickness absence and return to work (J-SAR) study. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemés, K.; Frumento, P.; Almondo, G.; Bottai, M.; Holm, J.; Alexanderson, K.; Friberg, E. A prediction model for duration of sickness absence due to stress related disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 250, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Barrachina, V.; Vanroelen, C.; Vives, A.; Martínez, J.M.; Muntaner, C.; Levecque, K.; Otros, Y. Measuring employment precariousness in the European Working Conditions Survey: The social distribution in Europe. Work 2014, 49, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morse, J. Researching illness and injury: Methodological Considerations. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, J.; Cassel, M.D. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. New Engl. J. Med. 1982, 306, 639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Boltanski, L.; Chiapello, E. El Nuevo Espíritu Del Capitalism; Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Woerkom, M.; Meyers, M.C. Effects of a Strengths–Based Psychological Climate on Positive Affect and Job Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R.; MacMillan, I. Gaining competitive advantage through human resource management practices. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 23, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. Fin del Trabajo. Nuevas Tecnologías Contra Puestos de Trabajo; el Nacimiento de Una Nueva Era; Booket: Madrid, España, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, M.; Zhang, Y.; Crawford, E.; Rich, B. Turning their Pain to Gain: Charismatic Leader Influence on Follower Stress Appraisal and Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1036–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Bontemps, S.; Barlet-Ghaleb, M.Z.; Besse, C.; Bonsack, C.; Wild, P. Protocol for evaluating a Consultation for Suffering at work in French-speaking Switzerland. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejours, C. Trabajo y Desgaste Mental. Una Contribución a la Psicopatología del Trabajo; OPS: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, S.; Rayner, C.W. Too hot to handle? Trust and human resource practitioners implementation of anti-bullying policy. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, M.; Hawkes, S.; Buse, K.; Nosrati, E.; Magar, V. Gender, health and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vallés, M. Cuadernos Metodológicos. Entrevistas cualitativas; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, España, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, D.; Gibson, A. Methodology in business ethics research: A review and critical assessment. J. Bus. Ethics 1990, 9, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, J. El Muestreo en la investigacón cualitativa. Investig. Soc. IV 2000, 5, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Haukka, E.; Martimo, K.P.; Kivekäs, T.; Horppu, R.; Lallukka, T.; Solovieva, S.; Viikari-Juntura, E. Efficacy of temporary work modifications on disability related to musculoskeletal pain or depressive symptoms—study protocol for a controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, C.K.; Hart, M.; Bhatkar, S.; Parker-Wood, A.; Dey, S. Access Prediction for Knowledge Workers in Enterprise Data Repositories. In Proceedings of the ICEIS, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 April 2015; pp. 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilahy, G. Organisational factors determining the implementation of cleaner production measures in the corporate sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartena, C.; Brussee, R.; Slakhorst, W. Keyword extraction using word co-occurrence. In Proceedings of the 2010 Workshops on Database and Expert Systems Applications, Washington, DC, USA, 30 August–3 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, E.; Paynter, G.W.; Witten, I.H.; Gutwin, C.; Nevill-Manning, C.G. Domain-specific keyphrase extraction. In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 99), San Francisco, CA, USA, 31 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, G.; Mampilly, S.R. Psychological empowerment as a predictor of employee engagement: An empirical attestation. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2014, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang-Woo, H. Roles of Authentic Leadership, Psychological Empowerment and Intrinsic Motivation on Workers’ Creativity in e-Business. J. Int. Comput. Serv. 2018, 19, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, F.W.; Lloyd, J.; Guenole, N. The work-related acceptance and action questionnaire: Initial psychometric findings and their implications for measuring psychological flexibility in specific contexts. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, D.S. Mindfulness in the workplace. Strateg. HR Rev. 2018, 17, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. How to win the war for talent by giving employees the workspaces they want, the tools they need, and a culture they can celebrate. In The Employee Experience Advantage; John Wiley Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.S. Happiness and Management. In Economics of Happiness; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hard-Lord, M.; Larsson, G.; Steen, B. Chronic pain and distress in older people a cluster analysis. Int. J. Nurs. 1999, 5, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, E.; Scharmer, O.; Eisenstein, C. The beginning is near. In Transformative Ecological Economics: Process Philosophy, Ideology and Utopia; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 186–204. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).