Impact Investing Strategy: Managing Conflicts between Impact Investor and Investee Social Enterprise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framing

2.1. Competing Logics as a Theoretical Framework for Impact Investing

2.2. Inter-Organizational Alignment among Impact Investors

3. Research Method

3.1. Case Selection and Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Cross-Case Analysis

4.1. Expectations of Social Impact Investors and Investees

4.1.1. Investor Expectations

‘Redefining the parameters of blockbuster success—a return of 5 to 10 times on invested capital …’ while ‘Investing in enterprises that gainfully engage rural and economically weaker sections of the populations either as producers, users or owners to deliver commercial returns.’(CEO AF)

‘We’ve done that [seek partners who wants to create systemic (normative) change through innovation, documenting and testing] with the India school leadership institute. We’ve just recently repeated that process with another institution we started called the education alliance. This is an organization that’s focused on public/private partnerships in education.’(CSF MD)

4.1.2. Investee Expectations

‘It was just me and a piece of paper, right. There was nothing on the ground’…’I needed five million dollars to just get started in the first place’…’there were very limited options [of investment], at that time, AF, I just came across them somewhere.’(Investee AF)

‘Impact investors should be putting a premium on impact, right? In terms of market valuation?’(Investee AF)

“‘We started our collaboration with a commitment that [the investors] are going to help us in providing all these [business skills], technical inputs and expertise.’(Investee USV)

4.2. Outcome of Non-Alignment of Investor—Investee Organizational Goals

‘If any of the Conditions Precedent mentioned in Annexure 7 including the investor code on ESG norms is not fulfilled or satisfied by the Long Stop Date, the Investors shall have the right to terminate this Agreement.’(AF legal agreement document)

‘They said you will never pay a bribe to a government official. I was laughing about it, because you know how the business is done in India.’(Investee USF)

‘[The investees] were not following the minimum wages and they were not taking care of [employment] needs in terms of proper working condition as agreed upon.’(Manager AF)

‘In the first meeting, they were asking me how will you give us an exit, I know of impact investors who also put such clauses that, in seven years or five years, you [the social entrepreneur] are forced to back the equity [return the investment] from the impact investor.’(Investee USF)

4.3. Pre-Investment Strategies for Effective Alignment

4.3.1. Due Diligence on Organizational Missions, Goals, and Actions

‘When an investment manager is doing the due diligence—even before the investment committee approves the investment—we go through a very detailed environment and social due diligence. We […] look at what the enterprise has done so far when it comes to environment and social impact. Going forward [we look at the] metrics that they would be measuring for us. [Only then do we] decide if we go ahead with the investment.’(Investor AF)

‘There maybe trade-offs at different times, on which markets you go after, I’m sure there will there will be kinds of conflicts. But what’s important is, that you choose entrepreneurs that you believe sort of have this similar DNA to what you have. If you select well there, then you reduce amount of conflicts.’(Investor USF)

4.3.2. Specialization and Sector Knowledge

‘We work in partnership with the municipal government’s schools we take over, and put in our own staff and teachers and run the schools according to our methodology. But the idea is then to transfer these acquired leanings to the rest of the government schools. So we do research and report our hypothesis, and then through policy advocacy to see that the effective practices are being implemented by the government.’(Investee CSF)

‘In microfinance actually it’s a very well documented model now, so we really can estimate all of these standard things, what should be the ideal holding period, what should be the stage at which you invest and what are the stages at which it should exit, for mainstream players.’(Investor LC)

4.3.3. Communication of Scalability and Earned Income Expectations of the Investee

‘Take, for example, RS [investee]. We invested when they had about one center and about 40 odd employees. Today they are among the largest player. So they run about 20 centers, employ 2500 employees in each of these places. On a commercial stand point, it now generates about 8 million dollars in revenues on an annual basis. Moreover, from an investment returns standpoint, I think we are close to getting an exit out of the center. We will basically be selling [to a] commercial player today and we are making a healthy return.’(Investor LC)

‘Any beneficiary should serve the low income either rural or urban [to guarantee social impact] community. Apart from these criteria we, when we do the inspection and developments, we look at financial scalability, and business scalability of fund (financial logic).’(Investor VI)

4.4. Effective Alignment of Competing Goals During Inter-Organizational Collaboration (Remedial strategies)

4.4.1. Social Impact Measures and Reporting

4.4.2. Engagement and Knowledge Sharing

‘As part of the mentoring we have regular board member calls with the enterprise. […] We find one of the CXOs, CIO, COO and the CEO related to the field. Our board members are really experienced guys in different sectors. Beyond [that], if we feel that an enterprise or an entrepreneur needs support for a specific thing or in a specific sector [and] we think that we cannot provide mentorship, we also connect them to a list of [outside] mentors on our website. They run multiple enterprises in different sectors and are really experienced people.’(Investment Manager VI)

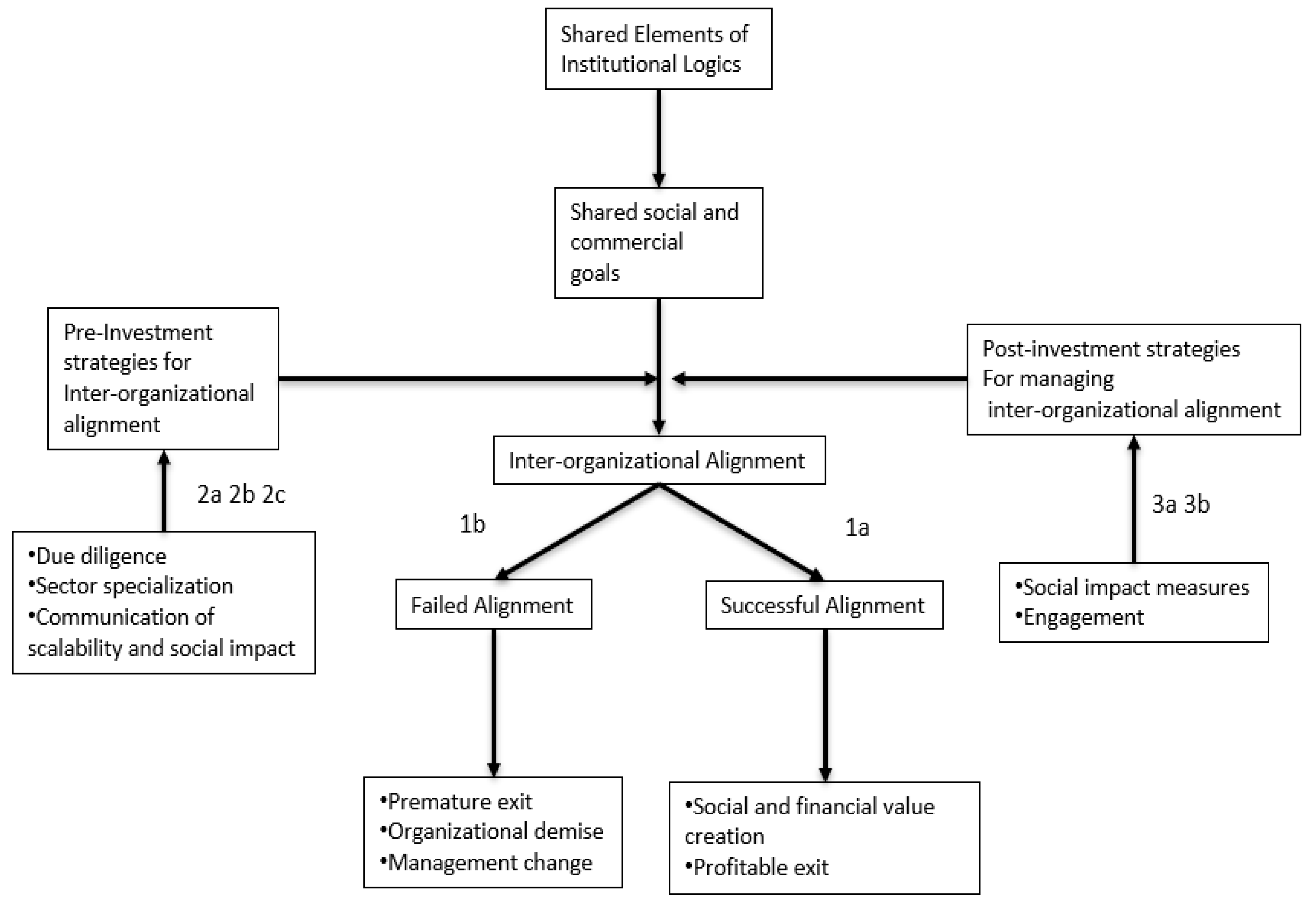

5. Discussion and Theory Development

5.1. Reasons for Alignment

5.2. Antecedents to Effective Inter-Organizational Alignment

5.3. Effective Long-Term Inter-Organizational Alignment

5.4. Inter-Organizational Alignment: An Investing Model

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Höchstädter, A.K.; Scheck, B. What’s in A Name: An Analysis of Impact Investing Understandings By Academics and Practitioners. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daggers, J.; Nicholls, A. Academic Research into Social Investment and Impact Investing: The Status Quo and Future Research. In Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance; No. 5; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hebb, T. Impact investing and responsible investing: what does it mean? J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2013, 3, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugg-Levine, A.; Goldstein, J. Impact Investing: Harnessing Capital Markets To Solve Problems At Scale. Community Dev. Invest. Rev. 2009, 5, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, A.T.; Koserwal, P.; Keerthana, S. The Global Epicenter Of Impact Investing: An Analysis Of Social Venture Investments in India. J. Priv. Equity 2014, 17, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M.; Walker, J.; Dorsey, C. In Search of The Hybrid Ideal. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/in_search_of_the_hybrid_ideal (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Miller, T.L.; Wesley, C.L. Assessing Mission and Resources for Social Change: An Organizational Identity Perspective on Social Venture Capitalists’ Decision Criteria. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, B.; Sievänen, R. Drivers of Socially Responsible Investing: A Case Study of Four Nordic Countries. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Introducing Impact Investing. In Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance; Lehner, O.M., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, F.; Pellegrini, C.; Battaglia, M. The Structuring of Social Finance: Emerging Approaches for Supporting Environmentally and Socially Impactful Projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Bengo, I.; Calderini, M.; Chiodo, V. Unlocking Finance for Social Tech Start-Ups: Is There A New Opportunity Space? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 127, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellas, E.I.-P.; Ormiston, J.; Findlay, S. Financing social entrepreneurship. Soc. Enterp. J. 2018, 14, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, N. De-Risking Impact Investing. World Econ. 2016, 17, 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Roundy, P.; Holzhauer, H.; Dai, Y. Finance Or Philanthropy? Exploring The Motivations and Criteria of Impact Investors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, 4th ed.; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, T.; Hinings, C.R.R. Managing The Rivalry of Competing Institutional Logics. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, O.M.; Nicholls, A. Social Finance and Crowdfunding for Social Enterprises: A Public-Private Case Study Providing Legitimacy and Leverage. Ventur Cap. 2014, 16, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Hockerts, K. Impact investing: review and research agenda. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.; Thornley, B.; Grace, K. Institutional Impact Investing: Practice and Policy. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2013, 3, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.C.; Santos, F. When Worlds Collide: The Internal Dynamics of Organizational Responses To Conflicting Institutional Demands. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Carranza, A.; Longo, F. Managing Competing Institutional Logics in Public-Private Joint Ventures. Public Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.; Santos, F. Inside The Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling As A Response To Competing Institutional Logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R. Conceptualizing the International For-Profit Social Entrepreneur. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Emerson, J. Maximizing Blended Value—Building beyond the Blended Value Map to Sustainable Investing, Philanthropy and Organizations; BlendedValue: CO, USA, 2005; Available online: http://www.blendedvalue.org/wp-content/uploads/2004/02/pdf-max-blendedvalue.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Davila, A.; Foster, G.; Gupta, M. Venture Capital Financing and The Growth of Startup Firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlani, D.; Mullins, J.W. Perceived Risks and Choices in Entrepreneurs’ New Venture Decisions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, J. Is Venture Capital Worth It? Effects on Firm Performance and Founder Returns. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.L.; Jeffrey, S.A.; Lévesque, M. Business Angel Early Stage Decision Making. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, D.; Dacin, M.T. Bankers At The Gate: Micro Fi Nance and The High Cost of Borrowed Logics. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltuk, Y.; Bouri, A.; Leung, G. Insight into the impact investment market: An in-depth analysis of investor perspectives and over 2,200 transactions. Available online: https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/Insight%20into%20Impact%20Investment%20Market2.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B.; Hardy, C. Inter-Organizational Collaboration and The Dynamics of Institutional Fields. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, B.; Nicholls, A. The Role of Legitimacy in Social Enterprise-Corporate Collaboration. Soc. Enterp. J. 2013, 9, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Fenema, P.C.; Loebbecke, C. Sciencedirect Towards A Framework for Managing Strategic Tensions in Dyadic Interorganizational Relationships. Scand. J. Manag. 2014, 30, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahnke, E.C.; Katila, R.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Who Takes You To The Dance ? How Partners Institutional Logics Influence Innovation in Young Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015, 60, 596–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, M.L.; Tracey, P.; Haugh, H. The Dialectic of Social Exchange: Theorising Corporate-Social Enterprise Collaboration. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. The Case Study Crisis: Some Answers. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 8–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W.; Wicki, B. Research Notes and Commentaries What Passes As A Rigorous Case Study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories From Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R. From The Editors: What Grounded Theory Is Not. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, M.E.G.K.M. Theory Building From Cases: Opportunities andchallenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, P.N.; Chatterji, A.K. Scaling Social Entrepreneurial Impact. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, F.; Fernandez, H. Strategies for Scaling Up Social Enterprise: Lessons From Early Years Providers. Soc. Enterp. J. 2012, 8, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Jmatthiesen, J.J.; van de Den, A.H. A Practice Approach To Institutional Pluralism. In Institutional Work Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations, 1st ed.; Lawrence, T.B., Suddaby, R., Leca, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 284–317. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building Social Business Models: Lessons From The Grameen Experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilcsik, A. From Ritual to Reality: Demography, Ideology, and Decoupling in a Post-Communist Government Agency. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1474–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Hardy, C.; Phillips, N. Instiutional Effects on Interorganizational Collaboration: The Emergence of Proto-Institutions. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Q.C.; Munir, K.A. Hybrid Categories As Political Devices: The Case of Impact Investing in Frontier Markets. Res. Sociol. Organ. 2017, 51, 113–150. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, R.; Hall, K. Social Return on Investment (Sroi) and Performance Measurement. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A. The Legitimacy of Social Entrepreneurship: Reflexive Isomorphism in A Pre-Paradigmatic Field. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 44, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Jarvis, O. Toward A Theory of Social Venture Franchising. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 30, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Levels of Differences/Institutional Logics | Commercial Logic | Social Logic |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Group/Individual owns the enterprise through investment or equity (Pache & Santos, 2011) | Group/Individual protects and spreads the social mission (Pache & Santos, 2011) |

| Sources of legitimacy | Return on investment, performance, effectiveness, efficiency (Nicholls, 2010) | Hero entrepreneur, beneficiaries, social change, disruptive change (Zahra, Gedajlovic, Neubaum, & Shulman, 2009) |

| Mission | Efficient allocation of resources; earned income while serving the society (Ruebottom, 2013) | Socially relevant and innovative solutions to serve the society (Neubaum, & Shulman, 2009) |

| Central values | Self-interest, consumer rather than the beneficiary, earned income, growth (Tracey & Jarvis, 2007) | Social value creation, equality, social justice (Zahra, Gedajlovic, Neubaum, & Shulman, 2009) |

| Model of governance | Governance towards defined objectives and performance, linear and rational (Ruebottom, 2013) | A democratic form of governance, high importance on the interest of beneficiaries (Ruebottom, 2013; Defourny & Nyssenes, 2012) |

| Logic behind decision | Profit maximization and fulfilling fiduciary duty (Battilana & Dorado, 2010) | Social value creation, welfare (Battilana & Dorado, 2010) |

| Data/SIVs | LC | AF | USF | USV | VI | CSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews with Investors of SIF | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interviews with Investees | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Interview with Fund Managers | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Documents | 50 pages | 400 pages: news, case study, contracts | 60 pages | 50 pages | 50 pages | 10 pages, YouTube, Website |

| Interview with Experts | Okapi India, Blended Value on India, GIZ India, Ashoka India, Fase-India | |||||

| Total Interviews | 29 interviews; 20–60 min | |||||

| Data/SIVs | LC | AF | USF | USV | VI | CSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founded | 2009 | 2002 | 2008 | 2011 | 2001 | 2012 |

| Founder Background | Developmental economist | Masters in management, with a focus on rural development | Love for India and background in financial services | Love for India and background in social services | Background in social services | Background in private equity |

| Type of Investment | Equity | Equity | Equity | Equity | Incubation and equity | Grant |

| Stage | Growth | Early stage and growth | Start-up, early stage and growth | Early stage | Incubation to growth | Growth and grant |

| Financial Funding | $50,000 to $2 million | $200,000 to $2 million | $50,000 to $2 million | $10,000 to $50,000 | $10,000 to $50,000 | $10,000 to $50,000 |

| Equity | 10–40% | 10–40% | 10–40% | Equity | Incubation and equity | Grant |

| Impact | Growth and capital-oriented social business | Difficult-to-reach, marginalized sections of India | The scalable base of the pyramid business ventures | Difficult-to-reach, marginalized sections of India. Early-stage investor | Social enterprises using innovation and design to address socio-economic problems | Improving the quality of education in India |

| Organizations Funded | 6 | 28 | 10 | 6 | More than 50 | 8 |

| Area of Operation | Microfinance, healthcare, food, education, technology, employment, agriculture | Microfinance, healthcare, food, education, technology, employment, agriculture | Greater focus on BoP innovation; microfinance, healthcare, food, education, technology, employment, agriculture | WISE, social inclusion, skill development, sustainable production | Technology-intensive social enterprises | Education |

| Types of Services Provided | Fund investment for impact, management support, market research, and network support | Fund investment for impact, management support, market research, and network support | Fund investment for impact, management support, market research, and network support | Seed fund, business mentoring | Seed fund, incubation, growth capital | Board position and management |

| Exit Strategy Planned | Yes, and succeeded | Yes, and succeeded | Yes, and succeeded | Yes, and succeeded | No | No |

| Structure of the Company | For-profit private equity firm and non-profit foundation | Group of companies addressing the market intermediary requirements of social entrepreneurship ecosystem in India | Group of companies, all of which focus on BoP segment in India Non-profit firm based out of the US for fundraising | Non-profit firm based out of the US for fundraising, Non-profit firm based in India for impact investment | Non-profit company based out of educational institute in India | Non-profit company |

| Type of Team | Founded by entrepreneur with experience in private equity and run by business graduates | Large interdisciplinary team led by social entrepreneur | Large interdisciplinary team, interdisciplinary advisers | Small team based in Seattle and small operational team led by established social entrepreneur in India | Large interdisciplinary team, incubated in a university office, large operational team led by a group of volunteers with previous entrepreneurial experience | Led by private equity professional with an operational team from non-profit social background sectors |

| Types of Investors | For-profit investors, HNIs, development financial institutions, foundations | For-profit investors, HNIs, development financial institutions, foundations | HNIs and foundations | Foundations | Foundation, Indian government agencies such as DST and Sidbi | Foundations such as Dell Foundation and Gates-Melinda Foundation |

| Social Impact Measures | Brief mention of the social impact | Elaborate reporting system, developed in-house impact-reporting measure with GIZ | Development focussed on the increase in earning, quality of life, quality of work condition | Focussed on social entrepreneur, impact created by the social entrepreneur in terms of jobs created, environmental impact, quality of services provided | Advanced measurement and elaborate reporting system | |

| Investees | Innovative rural education | Innovative fair wage dairy | Childcare | Employment exchange for the poor | High-tech service for the poor at reduced rates | Primary education for the working poor |

| Logic/SIVs | LC | AF | USF | USV | VI | CSF |

| Social Logic | Very low | Average | Average | High | Very high | Very high |

| Commercial Logic | Very high | Average | Average to high | Average to low | Low | Very low |

| Investor Motivation | Focus on return on investment, exits | Looks for a moderate return on investment | Looks for a moderate return on investment | Looks for a moderate return on investment | Looks for a low or very low return | No return on investment |

| Logic/Investee SoCents | Investee LC | Investee AF | Investee USF | Investee USV | Investee VI | Investee CSF |

| Social Logic | High | Average | High-average | High | High | Very high |

| Commercial Logic | Average | Average to high | Average to high | Average to high | Average | Low |

| Investee Motivation | Very high in terms of capital but very low in terms of engagement | Very high in terms of capital but very low in terms of engagement | Very high in terms of capital but very low in terms of engagement | Very high in terms of capital but very low in terms of engagement | Very high in terms of engagement and capital | Very high in terms of engagement and capital |

| LC | AF | USF | USV | VI | CSF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Investment Alignment Measures | Investee LC | Investee AF | Investee USF | Investee USV | Investee VI | Investee CSF |

| Due Diligence | Emphasis on earned income and profitability | Financial plan, location of the investee | Financial plan, beneficiaries, and their income | Rural location, financially social sustainable business models | Unique innovation for the social sector, financial plan | Innovation, financial plan, theory of change |

| Specialization | Expertise in microfinance | Diversified, highly structured, and well-defined management functions | Diversified, well-defined management functions | Poverty elimination through sustainable earned income | High-tech innovation to serve the poor; mentorship-based engagement | Primary education within government-run schools |

| Communication | Scalability and returns | Exit potential and social mission | Scalability, returns, and social problem (BoP); social innovation (BoP) | Social mission and earned income potential | Social mission and social innovation using technology | Social mission, social reach, and scalability potential |

| Post-Investment Alignment Measures | ||||||

| Engagement | Board membership, no-mentor program, little knowledge sharing, lack of field staff | Board membership, high knowledge sharing, limited by the lack of field staff | Board membership, little knowledge sharing, emphasis on investor-investee contract | Board membership, lack of engagement due to a shortage of staff | Very good and high impact mentorship program, good engagement with high knowledge sharing | Very good engagement in which the investor is engaged in each level of a theory of change |

| Social Impact Measures and Reporting | Less emphasis on social measures | High emphasis on social measures, dedicated staff for SIA | High emphasis on social measures, dedicated staff for SIA | Very high emphasis on social measures, dedicated staff for SIA | High emphasis on social measures | Standardized metrics to measure the theory of change, co-development of outcome measures |

| Performance | Profitable exits in the microfinance sector, social returns due to MFI services | Profitable exits in multiple sectors, higher social returns in multiple sectors | High focus on finance and peri-urban BoP social enterprises, moderate returns, moderate social value creation | High social impact, low financial benefits | High social impact, the investee social enterprises create long-lasting social value using innovative business models | High social impact through increased school test scores, emphasis on reporting, focus on policy change based on science |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agrawal, A.; Hockerts, K. Impact Investing Strategy: Managing Conflicts between Impact Investor and Investee Social Enterprise. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154117

Agrawal A, Hockerts K. Impact Investing Strategy: Managing Conflicts between Impact Investor and Investee Social Enterprise. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154117

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgrawal, Anirudh, and Kai Hockerts. 2019. "Impact Investing Strategy: Managing Conflicts between Impact Investor and Investee Social Enterprise" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154117

APA StyleAgrawal, A., & Hockerts, K. (2019). Impact Investing Strategy: Managing Conflicts between Impact Investor and Investee Social Enterprise. Sustainability, 11(15), 4117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154117