1. Introduction

The evolution of cities crosses different historical, cultural and technological periods. At every moment and in each geographic region, the demographic pressure introduces changes to the way in which cities evolve, requiring the development of structural and functional solutions as a response to the needs of human activities.

With the progress of society, the rapid urban growth associated with an intensive use of land and the inability to guarantee the adaptation to the constant and continuous change of its necessities, it becomes fundamental to promote new design strategies and approaches in order to transform today’s city [

1]. In this context, the regeneration of urban areas becomes a key objective, seeking to provide solutions that contribute to the revitalization and adaptation of the physical condition of both the built environment and open spaces of cities. Nevertheless, one of the challenges that urban regeneration has to face is the preservation of the identity and memory of places as well as the close relationship between the history of human activities and its spatialization. The functional requirements of the timing of interventions and their needs fall within a framework of sustainability and make it necessary for heritage to be safeguarded so that it can serve as a reference for future generations. This process of urban regeneration may acquire different modes of implementation, whether through interventions focused on time and space, or through public policies for attracting private sector investments. Regarding the latter, it is important that the public sector regulates and identifies what elements of built heritage preservation and protection should be ensured, and how the interventions in those buildings can take place. In this framework, a wide range of urban regeneration techniques have been developed, as the result of more than a century long history in studies on cities and urbanization. Indeed, the time period from industrial revolution to the 21st Century has drawn more attention from architects and urban planners than other periods [

2].

The role of cultural heritage in developing countries, namely in the Sub-Saharan African Region, has been discussed according to its importance [

3,

4,

5]. The immense economic, social and cultural changes that have occurred in these countries over time have resulted in a unique tangible cultural heritage [

2]. This uniqueness is associated with political [

6] and cultural factors [

7], but also environmental factors (the latter thought to be the adaption of western models to tropical contexts) [

4], mostly during the colonial period. Africa, namely the Sub-Saharan Region, has “(…) a double dimension, as both African and European regions, as a result of colonial influences of the 19th and 20th centuries” [

4], thereby possessing unique and important historical testimonies.

Cultural heritage has been referenced in the international agenda for development and sustainability, namely with Goal 11, Target 4, of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) regarding the action, to “Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” [

8]. Heritage preservation and for-profit use have the potential to promote social and economic development [

4,

5,

9].

Public authorities at national and municipal level both agree on the importance of preserving heritage but severe problems, such as population growth pressure, housing deficits and public health put aside wider urban strategies, where heritage is integrated, as part of the solution [

4,

10]. Thus, heritage can be included in urban regeneration strategies and approaches as important to economic development, but also social cohesion and cultural identity.

This paper presents a heritage-based method to urban regeneration, developed for the city of Luanda (Angola), within the elaboration of its Metropolitan Plan 2016. The city of Luanda provides a valuable case study for the discussion of how the urban regeneration process can influence contemporary public policies and planning at metropolitan scales. The challenges of the Luanda Metropolitan Plan include addressing the future urban development of a city with more than 6 million people and where 80% of the territory is covered by informal settlements [

11]. Nevertheless, the city has a unique and remarkable heritage, with historical buildings from the 15th century to the 20th century with the Modern Movement. After becoming independent in 1975, and the outbreak of civil war in 2002, several buildings have become a reference for their social, cultural and political significance and symbolism. In this framework, the proposed approach puts heritage in focus, aiming to demonstrate how its conservation and valorization in for-profit-use can contribute to urban regeneration in fragile territories, in terms of the social, economic and political context.

2. Literature Review

Heritage has been often discussed regarding its meaning, conservation actions and management approaches [

12]. Heritage is a collective property that shows the history of a society and territory and enables present generations to understand their place in history and thus, better cope with the transformations in society. Therefore, it is “(…) an element of stability in a rapidly changing world” [

3]. Several authors consider heritage to be a cross-cutting subject that can help with urban regeneration. [

13] state the potential of heritage within a social–economic context. Socially, heritage is a stable element that can help with social cohesion and inclusion, which are very important matters in developing countries, that is, regardless of the social status, age or gender, everyone belongs to a common identity. According to [

14,

15], in terms of economics, heritage conservation and valorization is commonly linked to tourism revenues, attraction of private investment and the creation of jobs. Of course, this latter aspect has strong implications for social aspects, since economic stability can help with the social development of the collective and individual. The social benefit of cultural heritage has been connected to the improvement of quality of life by “(…) providing a sense of belonging, creating pleasant environments, mitigating excessive urbanization, and adapting to climate change” [

3]. To reinforce that understanding, [

16] state that cultural heritage can contribute to the development of local communities and to the satisfaction of human needs. [

17] considers that the regeneration of historic urban areas has resulted in culture-led strategies that have had positive impacts in terms of social, economic and environmental aspects. For [

18], cultural heritage is an economic advantage within global competitive markets, because it provides cities with a unique identity.

Plans of main cities, such as the Italian cases of Gubbio and Vicenza, demonstrate the first experiences of holistic integration approach towards heritage, and then Urbino, Bologna and Ferrara follow with other experiences that consider the historical centers in an integrated approach towards urban development, with the focus on heritage buildings [

19].

In England, the cities of Bath, Chicester and York are the first cities that implemented urban restoration programs that view the protection of heritage buildings as a driver for development and regeneration in historical centres’ planning [

20].

However, heritage has complex meanings and its preservation is even more complex due to the diverse themes involved. In contrast to Western societies that are politically and socially stable, developing countries are not yet sufficiently mature to provide and define a clear view of heritage since the priority list of the local population is long. It is mostly due to the existing “informal” heritage marked by local identity (symbolic meanings) and community traditions, economy and routines, among others [

13]. This type of heritage is linked both to tradition and culture, considering the definitions of [

21]: compared with tradition, “(…) culture is almost always a process rather than a fixed, unchanging state of being and part of its unique character is precisely its ability to shape, shift and transform itself and the society producing it.” In constantly changing societies such as the African ones, this “informal heritage” is a significant issue to be considered.

Moreover, in territories that have major priorities such as a weak economy, issues with public health, social injustice and housing deficits, as is the case of Sub-Saharan African territories, heritage is set aside from the main actions for development [

22,

23]. The strategies currently applied are mostly landscape-based approaches that require an interdisciplinary understanding instead of the former idea of “untouchable” heritage. This approach was reflected in the UNESCO 1972 Convention principles that consider heritage to be “Monuments”, “Groups of Buildings” and “Sites” [

19]. Further, this definition evolved to a wider set of urban elements, including natural and intangible ones, such as, “Meeting Places”, “Remarkable Architecture and Urbanism”, “Public Space”, “Temples, “Agricultural Land” or “Sacred Mountains” [

4]. This means that heritage can be a part of urban planning. According to several authors [

19,

21,

24,

25], this integration requires the recognition of heritage values (e.g., historical, social, economic) and heritage-designated attributes (e.g., tangible and intangible) as well as the scale of urban landscape and its social, economic and environmental processes.

After the 1980s, urban regeneration based on culture began to form a huge wave, affecting regenerating projects throughout Europe, particularly through the development of cultural capitals as a successful solution to urban rehabilitation regeneration [

26]. The use of historical and cultural values as resources for development are the most important strategies in this policy. Responsible urban management authorities consider “culture” as an important instrument for urban regeneration and the value of the quality of heritage has been increasingly apparent as a part of innovations and initiatives for regenerating the city [

22].

3. Heritage Conservation in the Sub-Saharan African Region

Heritage in Africa is marked by a vast diversity that combines both local, European and American cultures [

27]. Even the latter is unique, because adaption processes occurred in these territories [

28,

29]. Moreover, this diversity mixes not only historical cities or buildings, but also many other forms of tangible heritage such as cities, cultural landscapes, places of memory or archaeological sites [

30]. According to the UNESCO guide for Africa, [

4] places of memory are highlighted due to the events of the past that took place in Africa. Most of these events are related not only to wars but also to hopes and aspirations. However, as [

31] indicated, regarding memorial heritage: “(…) the concept is useful for architectural historians because it reminds us, first, of the importance of the spatiality of memory, and, second, of the need to address not only the tangible but also the intangible aspects of built form.” Another type of heritage mentioned in this guide is cultural landscapes, that is, landscapes that result from the interaction between nature and man (e.g., a sacred tree, lake or mountain) [

4].

In many of the ancient African towns and cities, urban growth occurred around the city center which means that the historical core street pattern and buildings have remained unchanged [

28]. However, it is crucial to note that political conflicts have resulted in squatting (e.g., in Luanda, for example, several buildings that belonged to the Portuguese were occupied after the independence and are still occupied today) [

32].

The approach to these historical centers is a challenge for urban planners because of the “(…) increasing inner-city housing densities and expanding, large-scale commercial investment” [

28]. Although the most cost-effective solution is to relocate the residents of the city core, demolish the buildings and replace them with modern structures, some authors claim that social, cultural and economic potential is embodied in cultural heritage and thus can bring more long-term benefits [

28,

33,

34,

35]. Adaptive re-use is an alternative to demolishing, through the upgrading of the existing building stock and improvement of service provision, which has direct impacts not only on local community welfare but also within the economy, as a result of tourism [

36]. In fact, tourism can result in significant revenues where visitors may be attracted by the cultural authenticity of the rehabilitated area. Moreover, local traditions or activities such as handicrafts could also be a relevant aspect. Regarding social aspects, preserving heritage helps to maintain the social and cultural roots of the community, that is, promote social cohesion. According to Nayak [

34] in his experience in India, “Residents of historic city cores recognize these values and can become involved in the necessary conservation activities”. Community participation has an important role for the effectiveness of the solutions in terms of social acceptance as well as tourism (maintain heritage authenticity) [

33,

37]. Some experiences have shown that community participation in heritage improves sense of belonging and reflects a greater appreciation and understanding of the area value and potential [

38,

39]. A spontaneous participation model, in which residents have the power to make decisions and control the process [

40,

41], can generate trust, ownership and social capital among the residents [

42], in addition to the provision of adequate solutions that better satisfy needs and simultaneously maintain the authenticity and integrity of the intervention area. According to [

39], this participation model integrates early planning, the planning process itself and the monitoring/usage phase.

Examples of these approaches can be seen in Accra (Ghana), Zanzibar (Tanzania) and Saint-Louis (Senegal). These three cases are similar to the case study of this paper, Luanda, that is, former coastal cities with a structured urban pattern and architecture from the colonial period.

The historical core of Accra is marked by the coast line formed by colonial buildings from the 17th century, the port and the Jamestown lighthouse (the last two are related to the Ga Mashie people and fishing) [

33,

43]. The strategy, in partnership with UNESCO, was to improve the population’s quality of life through consideration of the historical building stock and the local economy (fishery). To start the project, a survey with the local population was done and the result was an inventory of all the historical and cultural (i.e., symbolic) buildings. One of the buildings was selected to accommodate a Heritage Center and eleven buildings were chosen for immediate interventions, within an incremental process. The Stronghold was accentuated, apart from these 11 buildings, due to its importance in the coastal landscape and urban fabric. Inventory supported, in a later phase, the creation of a touristic map and guide where the main “historical attractions” are highlighted.

Rehabilitation is considered to be self-building and thus using local building techniques, as well as, preferably, local materials. In addition to the rehabilitation of the building stock, the roads and adjacent public spaces, as well as all the docks, were also improved. For this purpose, several training courses and training for local guides were created. All training courses provided more skills to the local community and created new job roles (tourism, culture, commerce) and the improvement of the existing ones (fishery and trade). Socially, the project was very well accepted because people had a chance to proudly disseminate their culture and identity [

27].

Stone Town (historical urban core of Zanzibar) had a valorization and preservation strategy, within the Master Plan of Stone Town, as with the case of Accra. The rehabilitation was triggered by the touristic pressure of the region: while several touristic facilities were being created, people could not maintain and rehabilitate their houses that were mostly from the colonial period [

4]. In this case, the first phase was the rehabilitation of the colonial buildings to accommodate two Museums and a Heritage Center. A former English dispensary was adapted to house the center while the museums were accommodated in the Sultan’s residence/House of Wonders in the Palace Museum. The intervention in these three buildings embraced not only the building rehabilitation but also the requalification of the urban environment around them (roads, pedestrian zones, trees). Furthermore, several colonial buildings were transformed into hotels and training centers for the tourism sector.

The third selected example is the city of Saint-Louis, Senegal, formerly occupied by the French, whose heritage dates to the 19th and 20th centuries. A Safeguard and Development Plan was approved and implemented to protect existing buildings. Within this plan, several actions were conducted: a survey of all historical buildings and/or cultural buildings; identification of the cultural and historical value of each urban element such as roads, squares and buildings; and, most importantly, the creation of regulations and guidelines for heritage valorization and rehabilitation. These legal tools would be useful within the decision-making process both for local authorities and technical teams. Therefore, some of the regulations/guidelines consider the following: rehabilitation and reconstruction; license for demolition; building materials; colour palette to ensure the same aesthetical language; definition of protected areas (non-aedificandi) [

4].

These three examples are solutions, supported by UNESCO, that were applied in contexts marked by economic, social and political constraints. They show different ways to preserve heritage while developing the local economy and improving the social condition with communities. However, [

31] states that current approaches are still treating buildings as isolated objects, “(…) describing them in terms of formal appearance, technical innovation, and, in some cases, changes in use (…)”, following Western-based heritage practices. For this author, an alternative reading that re-situates buildings in their urban context is needed, because the “(…) choices of [these buildings’] location is seldom coincidental.”.

On the other hand, the reality of developing countries and the set of priorities that national authorities need to deal with do impose some restrictions on this action.

If we take into account that the vulnerability of heritage buildings is not a static issue, then we need to consider factors as: tenure of the land, urban planning, crime, security, cultural heritage and economy in urban centers. It is then easy to understand the difficulty in creating joint efforts to develop heritage preservation politics.

However, the need to discuss urban regeneration as a national priority to increase economic attractivity and to avoid urban degradation has been established in the discussion with present national authorities in the elaboration of the Luanda Metropolitan Plan 2016.

This paper presents a methodology for heritage preservation, valorization and requalification, developed within the Luanda Metropolitan Plan that is supported by a multi-layered approach for all urban, built and natural environments. It treats heritage as “urban sets” instead of isolated buildings. Here, the criteria to define the “urban sets” are much broader than merely being historical, integrating social, cultural and economic aspects focused on complementarity at both a local and national development level [

44].

4. Methodology

The methodology is based on a theoretical and empirical approach that considers the historical, social, cultural and economic dynamics as well as the territorial/physical urban environment [

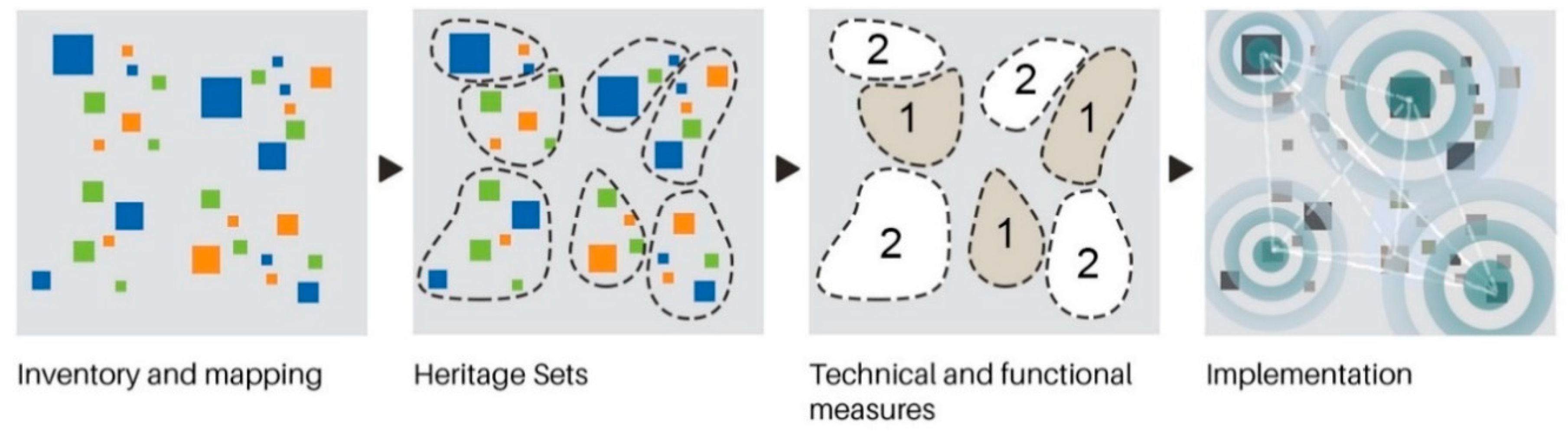

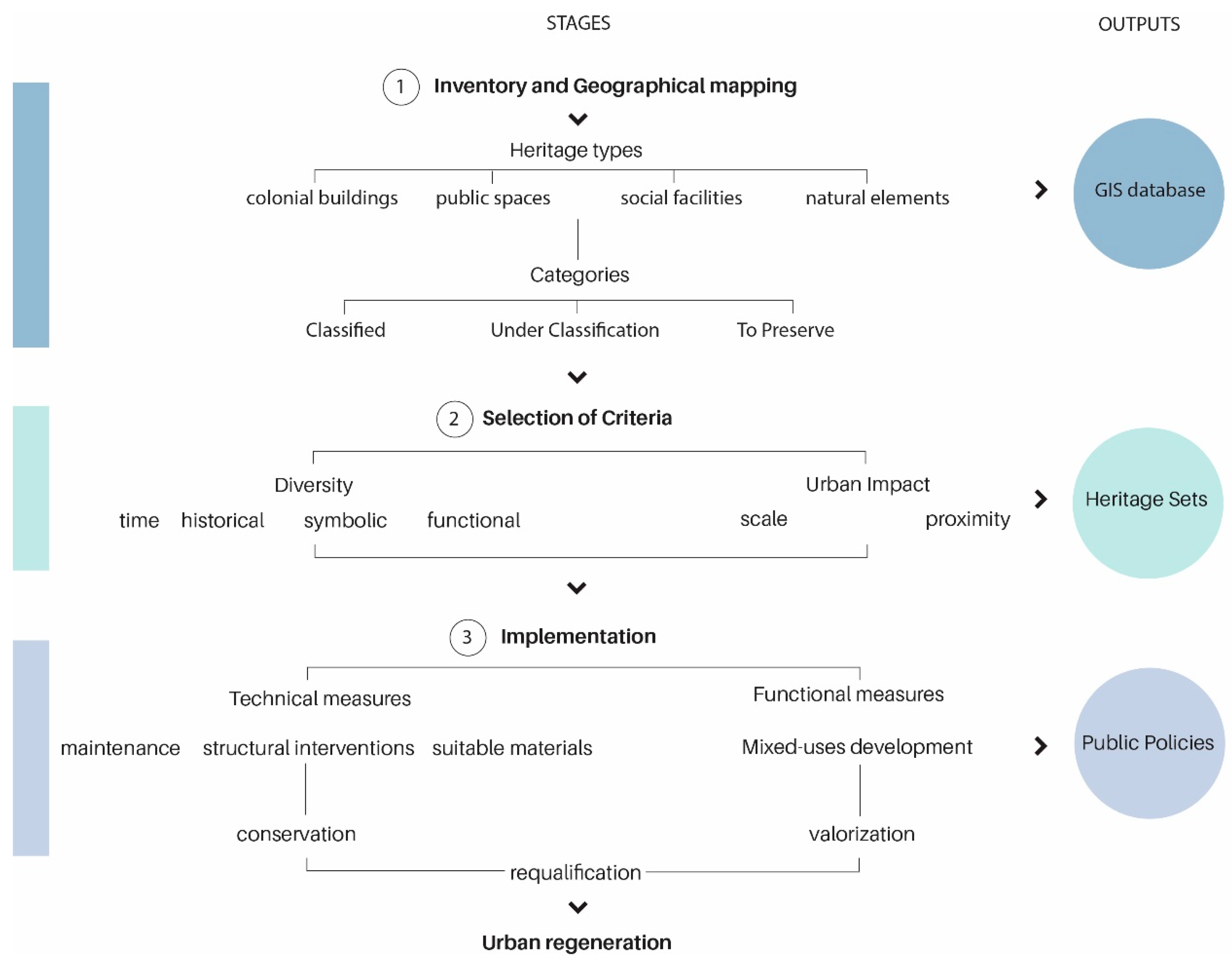

45]. A literature analysis on urban regeneration and its relationship with heritage was conducted, addressing the three main pillars of sustainability: economic, environmental, and social. Moreover, as heritage is the fundamental issue in this approach, the cultural and identity values were examined in even greater depth. In the literature review process, articles, books and other sources have been divided between those which provide ‘scientific’ research-based methodologies—whether empirical, using quantitative and/or qualitative surveys and those which are illustrative, with descriptive reference to practical case studies. To give an operational link between the aforementioned framework and the complexity of the city scale, a conceptual approach based on the geographical urban delimitation of “Heritage Sets”, instead of isolated buildings, was then adopted (

Figure 1).

Appealing to the cellular automata theory, the geographical urban delimitation model assumes the division of the city into “cellular units” according to delimitation criteria [

47]. As a result, a three step methodology on how to develop a heritage-based urban regeneration process was then created and applied to the city of Luanda (

Figure 2).

The first step refers to the time and geographical mapping of historical, social and cultural heritage in the city. To help with the definition of the types of heritage included in these criteria, the Cultural Heritage Law (Law nº14/05 of 7 October) was consulted to understand the current situation of heritage in Angola. This Law enabled verification of heritage labelled as “Classified”, “Under Classification” and “To Preserve”. Moreover, it was possible to check the type of heritage included in these categories, such as colonial buildings, public spaces (e.g., squares), social facilities (e.g., hospitals/schools) and natural elements (e.g., sacred trees). The Municipal Plans also provided essential data on “Heritage to Preserve”, that is, important sites/buildings for the local community that, in some cases, do not have any architectural or historical value. Following the work of [

31], this research has been complemented with a literature review to better comprehend the context and the historic dynamic. In addition, the assessment of building conditions has been done through fieldwork, because most of the provided data was outdated. All the data resulted in a GIS database, with all the information of every element.

The second step deals with the selection of criteria for the delimitation of the Heritage Sets across the city. Heritage sets are formed by several buildings/sites that form an urban unit, criteria of which are based on the concept of “Diversity” and “Urban Impact”.

Regarding “Diversity”, criteria such as time, historical and symbolic diversity as well as functional diversity were considered. Time diversity considers elements from several historical periods that can create a heterogeneous urban set in terms of aesthetics and language. Historical and symbolic diversity refers to elements with different symbolic meanings and forms from different historical periods as well as the cultural and social dynamic. In Angola, this is a relevant factor because of all the transformations that occurred over time, from the Portuguese occupancy to the creation of the Angolan nation. Finally, functional diversity considers the former and current use of the identified heritage. The assessment of these uses will help to fulfil local needs: What uses are needed? Is it possible to adapt the current use or recover the previous use? How can this adaption be achieved? Moreover, this assessment will allow for establishing a framework for complementary uses while defining the Heritage Sets.

Regarding “Urban Impact”, as the potential to disseminate the regeneration process to the surrounding areas, the criteria are based on scale and proximity. Some heritage elements, due to their scale, have a spatial incidence which is independent from other buildings or public spaces. Proximity is linked to the socio-economic organization of the surrounding areas and the potential framework for the development of mixed-use models that they can offer. This is the case of those surrounding areas where the provision of services and goods follows some economic rules that can be associated with an informal market structure, providing a livelihood to many. In this way, the conservation and valorization of different Heritage Sets across the city performs as an urban regeneration process that works according to a network structure within which there is a hierarchy and a flexibility of interventions, based on the heritage itself and its local context.

The third step consists of the implementation phase and it is the most important step, because it leads with the decision-making process to support the elaboration of public policies. Here, Heritage Sets with higher potential for improving the surrounding area or providing faster revenues are identified to develop technical and functional measures.

After the assessment of the building conditions and former/current use during the first step, it is possible to create technical measures to improve the quality of the building, including maintenance practices, structural interventions and use of suitable materials for its conservation. Whenever possible, these measures can be supported by legal tools such as specific regulation for heritage or building codes. Functional measures refer to a phased mixed-uses development plan that involves planning for residential, hotels, religion, commerce, culture (museums, cultural centers, cinema and theatre), social (library, civic centers), parks, sports and open spaces (

Table 1). The functional matrix is designed according to the results collected from step one that might vary depending on the territory.

The methodology will allow for the conservation, valorization and requalification of both built heritage and urban environment. The technical measures in the buildings will ensure the physical conservation of heritage types identified and reinforce their durability and sustainability. The conservation of heritage takes in account the form and design, the materials, use and function, techniques, location and ambient values. Valorization (added value) will be promoted by the functional measures which are defined for each Heritage Set. Requalification is the wider outcome at urban scale, seeking to integrate heritage in urban planning as a driver for urban regeneration.

5. Case Study

The methodology developed in this paper has been applied to the city of Luanda, which is described in this section as the case study. Luanda’s heritage covers several periods, such as: the foundation period, the 15th century marked by the Portuguese strongholds, fortresses, trade ports and churches; in the 19th century, due to Brazil’s independence, the Portuguese started to invest more in Angola as the main trade node of the empire, which resulted in the construction of many palaces and manors as well as many major facilities of the 21st century (e.g., Hospital Josina Machel in Luanda, classified as heritage since 1981,

Figure 3) and infrastructure (Bungo and Cidade Alta train stations classified as heritage since 1992,

Figure 4); the 20th century was marked by the Modern Movement, where architects and artists, oppressed in the motherland, could freely express the modernist ideals and values; later, after the independence (1975) and the consequent civil war until 2002, several monuments with symbolic meaning were created and further labeled as “Classified Heritage” (International Charters on Urban Conservation, 2007). Therefore, heritage in Angola, namely in Luanda city, is as a result of different historical periods, which allow for the identification of different styles of architecture, languages, formalisms and meanings. However, it is essential to note that in the case of Luanda, Modern buildings, regardless of their architectural value, were not attributed any label as far as being not yet covered by any legal protection at national or local level. Within this research, 20 modern buildings have been identified in the city center of Luanda, part of them in precarious, but fully operational condition.

Despite this inventory, social and economic problems (poverty, public health, crime) are still a priority while dealing with urban regeneration. Notwithstanding these issues, the methodology is that heritage conservation and valorization can contribute to the urban regeneration, resulting in social and economic positive impacts, which will not solve the aforementioned problems, but can help with finding the solutions [

46].

The first step was the identification of heritage and its classification. For this purpose, the data from the Ministry of Culture and Municipal Plans within the Region was consulted. The Ministry provided information about the “Classified” and “To Classification” while the Municipal Plans (Cazenga, Sambizanga and Rangel Plan; Viana) provided information about heritage with the intention “To Preserve” (due to its cultural interest).

This intention is related with the assumption of important heritage for the local community which requires an action of protection. A total of 146 heritage buildings/sites were identified, with 72 as “Classified Heritage”, 53 labeled as “To Classification” and the remaining 21 categorized as “To Preserve”. Around 90% of these surveyed buildings are in Luanda city center and can be summarized as shown in

Table 2.

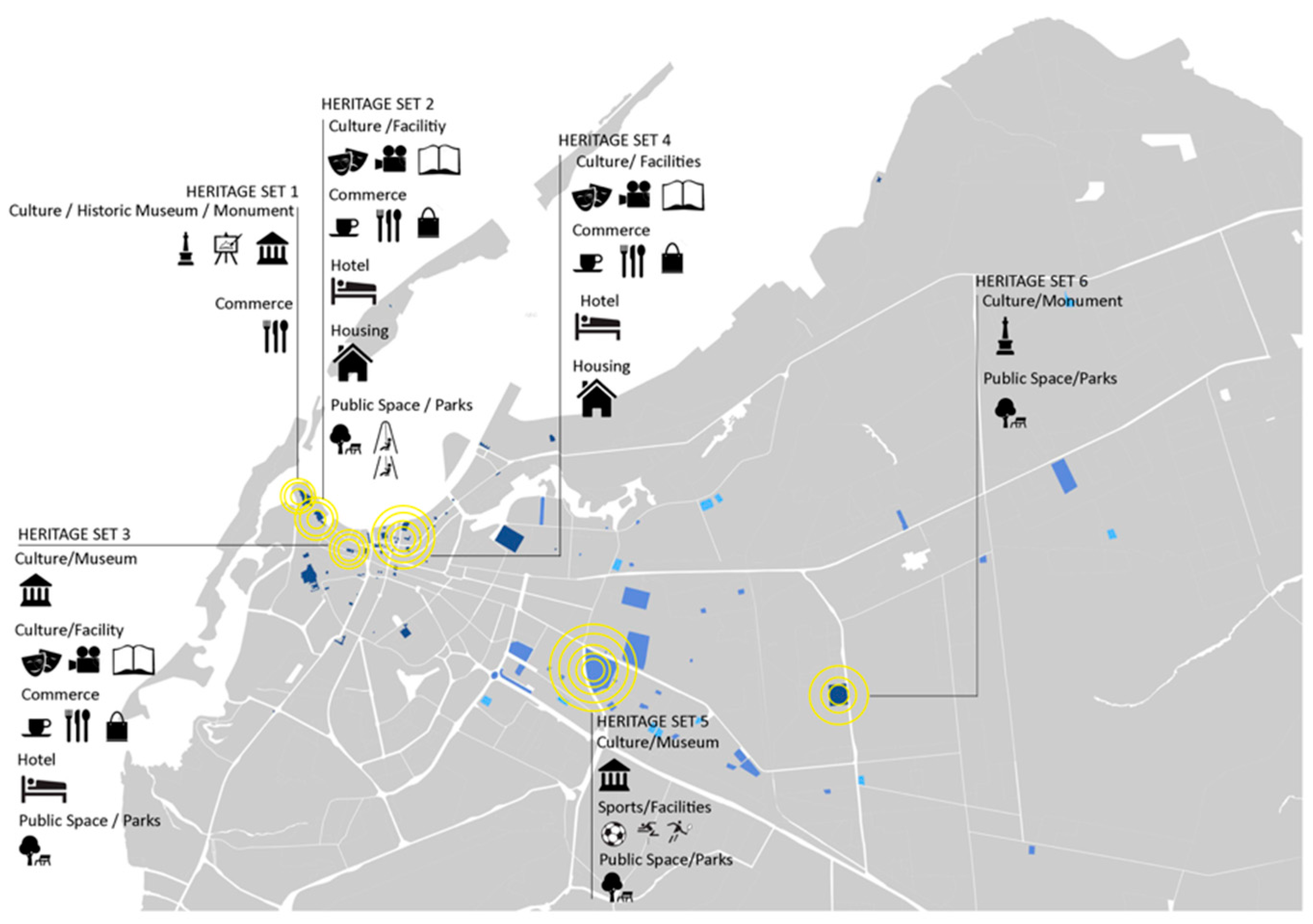

Based on this information, the “Heritage Sets” were then defined. Regarding the objectives and development goals of the Metropolitan Plan, seven sets were defined as major poles to support regeneration alongside with other sectorial strategies for the Province. Heritage Sets 1, 2, 3 and 4 are in Luanda Municipality (city center) while Sets 5 and 6 are in Cazenga Municipality and Set 7 is in Viana Municipality.

This “set” is formed by a single building that has enough scale to propitiate urban regeneration by itself. The building has been classified as heritage since 1938 and refers to a former fortress that is today a museum and a viewpoint over the waterfront (

Figure 5). Conservation state is satisfactory, and the building is fully operational. This set is directly connected to Heritage Set 2 due to the proximity and its functions related to tourism (hotel), culture and commerce. This Heritage Set is aimed at the touristic sector.

Baleizão Square (former Largo Infante D. Henrique) has been classified since 1992 as the more expressive example of this methodology. The Square combines several buildings with different and complementary uses of various historical periods. This context relates a real architectural dynamic of the set (

Figure 6). The buildings involved are the following:

- -

Manors from the colonial period, currently classified but abandoned or in a precarious condition, capable of serving mixed functions: commerce on the ground floor and tourism apartments on the first floor. However, it needs major rehabilitation procedures in terms of structure (masonry) and finishes.

- -

The building of Companhia Geral de Angola, also classified since 1992, is currently on rehabilitation (

Figure 7). Its size and location are suitable to accommodate a social or cultural facility, containing both the local population and tourists. Moreover, this use will also provide support to the functional adaptation of the colonial manors.

- -

Baleizão Square, which has been recently rehabilitated, the central urban element to organize the surrounding buildings and their functions. Due to its scale (around 1600 m2, this square can accommodate a small kiosk to attract more people and provide a spot to stay. This urban element creates a connection to the Fortress (Heritage Set 1).

In addition to the elements mentioned above, the square contains some residential buildings from the 1970s that, apart from their conservation state, are still operational. These buildings will give a “community dynamic” to this area due to the existence of local population. Therefore, Heritage Set 2 is aimed at tourists as well as the local population, also having a function of public space for city regeneration and the improvement of quality of life.

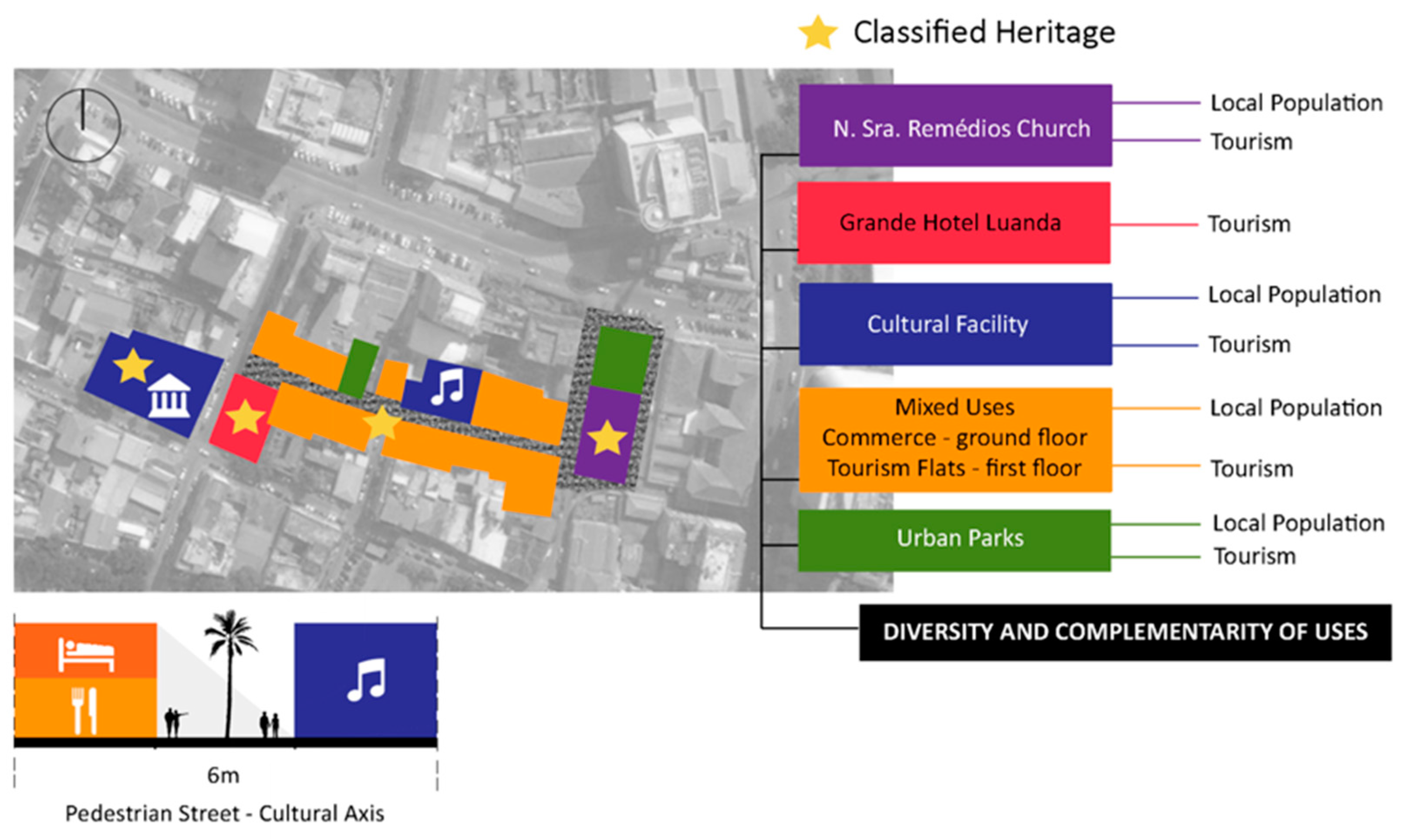

Mercadores Street is another excellent example of diversity and, compared to the other Heritage Sets, contains four classified elements, two of which are in exceptional condition and are fully operational: National Museum of Anthropology (18th century) and the Church of N. Senhora dos Remédios from the 17th century, classified since 1945 (

Figure 8), have been rehabilitated and are fully operational within their functions; the Mercadores Road, formed by colonial buildings from the 17th to the 19th centuries, and Grande Hotel Luanda (20th century) are in precarious condition, the latter that is even in advanced decay. Therefore, we have four elements with origins in different periods of time and with several functions and complementarities.

The first action aims at rehabilitating the Mercadores Street because it is the main axis between the Museum, the Grand Hotel and the Church. Therefore, a cultural axis, focused on tourism, can be implemented in this street in order to complement the existing functions. Mercadores Street contains two storey residential buildings formed with large windows and balconies. Thus, a mixed-use scheme is proposed, particularly, for the ground floor, which is occupied by commerce and the first floor, which is occupied by tourist apartments (although there is no view to the bay, the colonial context and the central location near the main cultural sites can be an important attraction factor). Moreover, one of the buildings (a former manor with a courtyard), will accommodate a cultural facility for both tourists and local population. Due to the state of decay of one of the buildings, it will be demolished and transformed into a small square as an open space in the urban structure. Furthermore, this street will be turned into a pedestrian street only for two main factors: it is a secondary road with viable alternatives nearby; it is a narrow road with about 6 m width and the building does not exceed 6 m height, which gives it a “human scale”; the latter creates good conditions for implementing local commerce.

The second action is the requalification of the churchyard of N. Senhora dos Remédios Church in Luanda’s Waterfront. Most of the tourists come from the Waterfront, the most attractive site of Luanda. The rehabilitation of the churchyard can be the entrance to the “colonial city”. Thus, its connection to the Mercadores Street (cultural axis) can establish an urban unit among heritage elements.

The last action, more expensive and time-consuming, is the rehabilitation of the Grande Hotel Luanda. The building is already marked to be rehabilitated, but its state of decay will require major transformation. Only the façade can be maintained.

This Set is aimed, mostly, at tourism but also, the Church and the Museum, at both ends of the axis, are important services for the local population.

Heritage Set of Mercadores Street was considered a pilot project within the Metropolitan Plan, (

Figure 9) (

Table 3), because it joins the strategic position in the historic urban matrix with the use and function of buildings and public space. Rehabilitation also promotes important social capital and brings environmental and economic advantages, such as reducing energy consumption and CO

2 emissions.

This Set is formed by two major arteries (Kanhangulu Street was the Rua Direita of Luanda, the main artery of the former Portuguese settlements) in the city that are also a major part of the classified heritage, namely the colonial manors that are currently being used as administrative buildings, the train stations of Cidade Alta and Bungo, some churches, and the Iron Palace (Palácio de Ferro) (

Figure 10), one of the main attractions in Luanda. Thus, several buildings related to services are shown in this area: culture (the Iron Palace), commerce (Lello Bookstore is highlighted,

Figure 11)), administrative (e.g., Cultural Heritage Institute) and infrastructure (the train stations).

These two streets are part of an integrated process that will be slower than the previous sets, due to their width and distance between the buildings. This means that their dissemination will be at a local level instead of having a wider impact. Regarding rehabilitation, the buildings of the set are in acceptable condition because most of them are being used as administrative buildings by the government. This set is aimed at the local population by providing services.

The Sports Citadel (Cidadela Desportiva), built in the 20th century, is in itself a Heritage Set due to its scale within the city (

Figure 12). The complex is “To Classification” and contains not only sports facilities (gymnasium, playing field among others), but also the Sports Museum. Moreover, it is in a residential area, becoming an important social facility for the local population. Although Heritage 5 is in another Municipality to the previous ones (Cazenga), these sets are very close to each other, enabling a future connection between them.

Heritage 6 is the S. Miguel Fortress (Set 1). Its scale and symbolism (are categorized as “Classified” heritage) make a unique element as a set by itself. The landmark symbolizes the beginning of Angola’s independence in 1961 and is significant not only at the local but also national level. This Heritage Set has a special feature compared to the others, as it is integrated in a large urban park, having the function of a monument but also a public space in order to serve the community. The conservation state of this building is satisfactory, not only as the landmark but also as an urban park. As Heritage Set 5, the landmark is also located in Cazenga Municipality that is adjacent to the city center.

Figure 13 translates the spatialization of Heritage Sets 1 to 5 in the city, the types of Heritage that the Sets add and the visible distribution of the same in the city. The map makes understandable the concentration of the Heritage Set’s group in the oldest part of the City, which, if analyzed in light of the city’s growth and morphological pattern, is self-evident in terms of historical development.

The Historical Center of Viana is in Viana Municipality, far away from the city center. Although it does not have any classified heritage (except for “To preserve”), this set contains many important buildings for the local community and organizes the urban center of this municipality. Its dissemination potential results from the diversity of uses—health care, religion and culture. The buildings that form this set are as follows: Nossa Senhora da Anunciação College (religion), Viana Church (religion); Red Cross Building (health care); and Kalumbe Cinema.

Moreover, its proximity to Catete Road (the main entrance to the city) can help with the connection to the other sets, namely due to the development of public transport and mobility corridors proposed in the metropolitan plan.

Within the defined sets, some specific elements can be considered as regeneration cores, that is, the main elements to begin regeneration. Such elements are also attraction points for tourism and services (the latter of which is aimed at the local population). Moreover, these cores, due to their importance and symbolism, will support the remaining uses to foster urban regeneration. The criteria of these heritage sets include both tangible and intangible characteristics of the buildings or monuments. The goal must be to reuse these socially recognized elements in a way that allows for its contemporary use by tourists and local population.

Therefore, the regeneration cores are as following: S. Miguel Fortress, due to its unique value as a historical and cultural asset at national level; Nossa Senhora dos Remédios Church due to its architecture and historical value (one of the first churches to be built by the Portuguese in Angola); the Sports Citadel due to its social role for the community as well as its potential to be a tourism asset due to the Sports Museum; the 4th February Landmark, which is an important memory for the Angolan nation, aimed not only at tourism (to disseminate the Angolan history) but, most importantly, for the Angolan population, as an element of collective memory [

33,

49] (

Figure 14).

6. Discussion

The economic development, resulting from the phenomenon of globalization and population growth, has been a cause for concern due to the continuous destruction of natural resources, rural areas, historical urban centers, villages and monuments. Overall, the expansion of urban areas has resulted in an uncontrolled process of urbanization, accompanied by an overproduction of goods with innumerable related problems of a social and environmental nature, regarding affordable housing, security, quality of life, climate change as well as the responsible preservation of local identities and cultures.

Cultural heritage is discussed in the SDG, Goal 11, Target 4, namely in the Sub-Saharan Region that has unique and valuable examples of the historical heritage which is in severe risk of decay. Public authorities have already recognized the importance of preserving cultural heritage but the lack of financial means and other priorities (such as social–economic issues and the housing deficit) have set cultural heritage aside. However, this subject has been discussed and some authors agree that heritage can be integrated into planning strategies as a contribution to urban regeneration [

45]. Moreover, the population can also contribute within the whole process, since, for the people, the identification of valuable heritage (historical, cultural and social) and the definition of design value are some of the best ways to preserve, disseminate and use such heritage. Three examples, supported by UNESCO, are presented: Historical Centre of Accra and Stone Town in Zanzibar, where the community participation, public space improvements and the implementation of social/cultural uses in the built heritage are highlighted; Saint-Louis, Senegal, that has created regulation and treated heritage as urban sets. From these examples, it is evident that heritage can be an important economic and social asset within developing societies.

Given the need to adapt cities to the evolution of human activities, it thus is critical to encourage the integration of heritage conservation and valorization into public policies and local planning practice. In this vein, this article presented a methodology for urban regeneration supported by the conservation and enhancement of heritage and local history and culture. The approach considers the conservation and valorization of a set of built heritage, rather than only one building. The definition of these sets is based on Diversity and Urban Impacts, that is, diversity of uses, historical periods and symbolisms as well as the scale to disseminate its influence on the surroundings. This will increase the impacts over the city both at urban and social–economic levels and will treat “Heritage Sets” as spatial regeneration units.

The methodology consists of three steps: inventory and mapping, definition of criteria for the delimitation of Heritage Sets and implementation, involving technical and functional measures. Mapping and inventory processes with GIS database are essential to further phases, namely the definition of the “Heritage Sets” because they are defined historically but also geographically. Technical measures will ensure the conservation of the building stock, while functional measures based on mixed-uses development will ensure profit (e.g., tourism and commerce) and services (e.g., social facilities, administration).

In the application of the methodology to the case study of Luanda, 146 heritage building/sites were mapped, where almost 50% is “Classified”, 35% is “To Classification” and 15% labeled as “To Preserve”. A total of 90% of these buildings/sites are in Luanda’s city center. Seven Heritage Sets were identified, two of which are single buildings with enough scale to propitiate wider impacts (Heritage Set 1—São Miguel Fortress; Heritage Set 6—the 4th of February Landmark). The remaining heritage sets (HS) are formed by several buildings, from different historical periods and with different (and complementary) uses: HS 2—Baleizão Square; HS 3—Mercadores Street; HS 4—Major Kanhangulu and Rainha Ginga Streets; HS 5—Sports Citadel; HS 7—Viana City Center. The latter is the only one that does not have Classified heritage, but rather, “To Preserve”, to the extent of the buildings being socially and culturally important for the local community. HS 3 was considered a pilot project due to its potential to generate impacts within the city. Diversity of uses and architecture from different periods gives to this HS enormous potential. Moreover, this example has four elements labelled as “Classified Heritage”, namely the whole street, which grants a great potential to attract investment. While some HS focus on tourism, others are aimed at the local community, through the provision of services.

This methodology can be replicated for other cities in developing countries that must face the urban regeneration challenge. Indeed, the rehabilitation of the heritage which is the image and the identity of the past and of the present of built environment can be a fundamental aspect in the urban regeneration process in developing countries, which have often suffered periods of occupation by other countries. Here, heritage allows people to identify the cultural and social dynamics and the model of evolution and expansion of a city, which is important for laying down a solid urban regeneration framework and creating a new cultural tradition.

In Angola, this is a relevant aspect and the elaboration of the Luanda Metropolitan Plan was an opportunity to look at strategic territorial planning as a tool to preserve and promote the historical period that goes from the Portuguese occupation to the creation of the Angolan identity and nation.