1. Introduction

Companies and people are interested not only in economic benefits and profits but also in social sustainability. In order to build a good corporate image and enhance customer loyalty in the long run, companies are strengthening their corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities related to the industries they belong to as well as to the socially underprivileged and the environment [

1]. Individuals are also making efforts to promote social sustainability in a variety of ways, from changing small lifestyle habits such as buying environmentally-friendly products and making sure to recycle used products [

2] to more active acts of donating money and time to the areas of their own interests such as culture, art, the environment, education and women’s, children’s and poverty issues. Considering that private donations in the U.S. (in the amount of US

$286.65 billion) accounted for approximately 70% of the total U.S. donation amount of US

$410.02 billion as of the end of 2017 [

3], individuals’ donation activity is an important aspect of social sustainability [

4]. Donation campaigns that lead to individual donations are generally planned and promoted through various non-governmental organizations (NGOs, non-profit organizations, e.g., UNICEF). At this time, Most NGOs seek ways to improve communication strategies and donation participation methods based on a deep understanding of potential donors in order to increase campaign performance. This situation is similar to that of a commercial enterprise trying to establish an effective marketing strategy for consumers in general consumption situations.

In this study, we focus on using digital means (e.g., online media) as a method to increase the number of opportunities individuals have to donate. Digital markets are growing rapidly in the marketplace of general offerings (goods and services), and this trend is the same in the donation market. This donation trend gives non-profit organizations and individuals that seek to raise funds access to more potential donors without the constraints of time and physical distance and allows individual donors to search efficiently for information on donation opportunities, promoting participation in donations. According to consumption data from Mastercard users [

5], personal online donation behavior in the U.S. has grown steadily from 4.8% to 11.4% annually during the period 2010 through 2017. This is about twice as much as in-person donations as of 2017. In China, which has the fourth-largest number of donors in the world, global companies such as Tencent and Alibaba are also paying attention to the growth potential of online donations and investing in building online donation tools [

6]. In sum, understanding and researching donation activities via online platforms is a vital topic for both researchers and practitioners who design donation marketing. Therefore, this study mainly aims to investigate the mechanism which determines the donor’s willingness to donate in the online context.

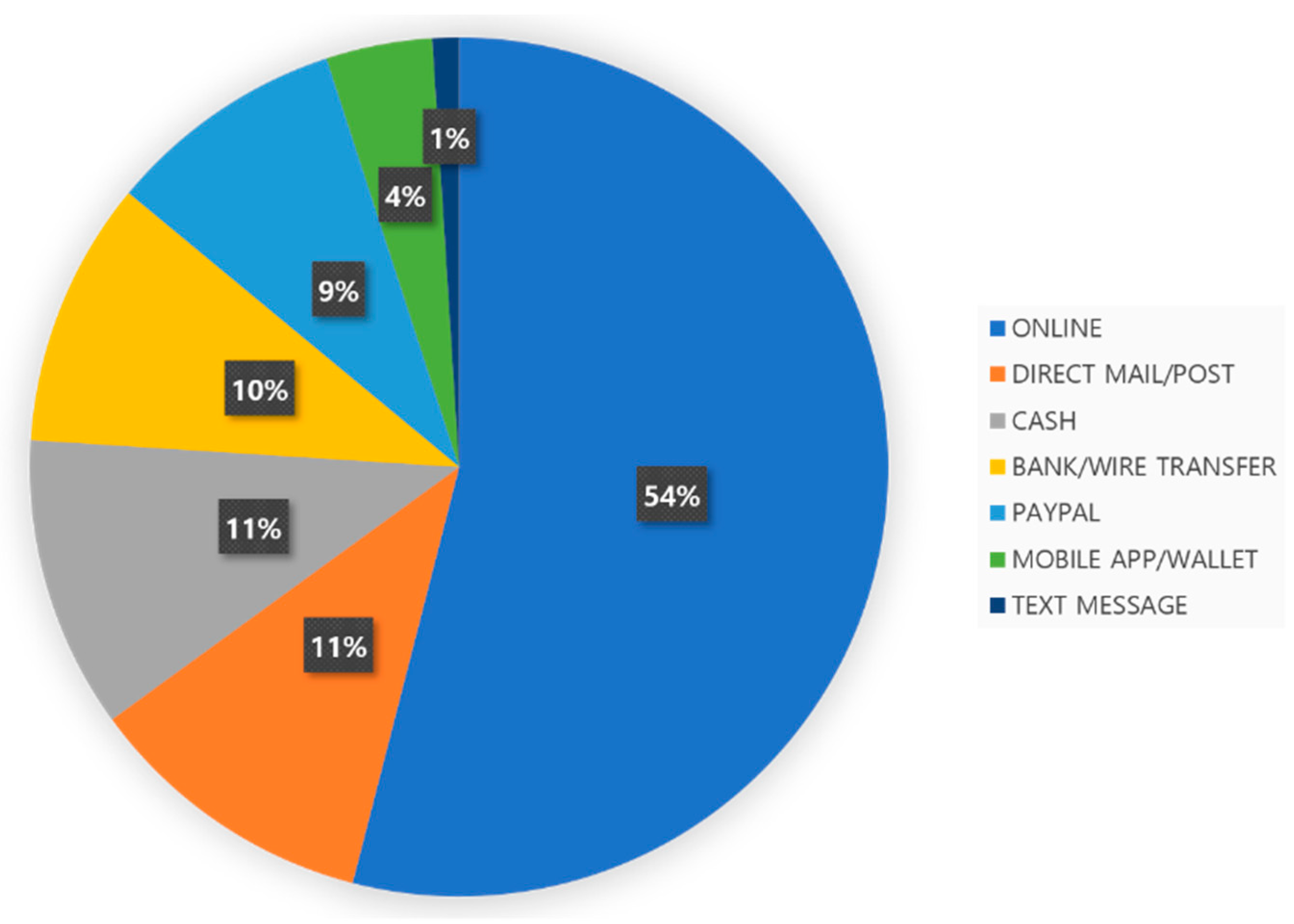

According to a 2018 report on giving [

7], 54% of donors across the world prefer making donations through credit or debit card followed by 9% through PayPal. Donors tend to make fewer donations through mobile apps/wallets (4%) and text messages (1%). See

Figure 1.

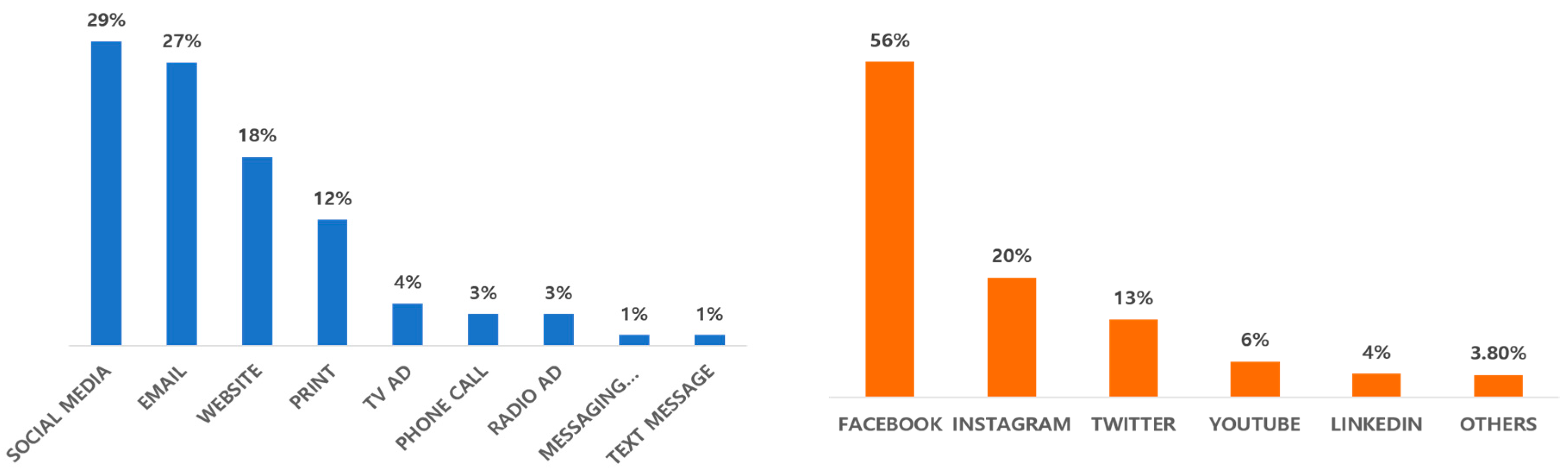

As seen in

Figure 2, 29% of donors across the world say that they were inspired the most by social media to make donations. Among the donors inspired by social media, 56% replied that they were the most inspired by Facebook, 20% said Instagram and 13% said Twitter. Furthermore, 18% of donors across the world made donations to charitable organizations directly through Facebook, and 88% of these donors said they prefer to give through Facebook again. Facebook stands on top among all social media across the world. Its new tools for fundraising will likely transform giving on a global scale. This report [

7] tells us that online fundraising is driven by peer-to-peer platforms which solicit donations through individual networks such as SNS.

The advent of social media has changed peer-to-peer fundraising in that it reduces costs for the fundraiser and, at the same time, makes it easier for potential donors to participate. Ultimately, it can be concluded that the relationship between SNS users and their social networks affects donation behavior. For example, the Ice Bucket Challenge became a global sensation that attracted donators worldwide in a short time without spending much money using the method of early participants attracting the next participants through human networks on SNS.

This study looks into online campaigns, a very effective donation method in this age of ever-increasing interest in social sustainability, and aims to find out the characteristics that influence individuals’ responses to these campaigns. Specifically, this study focuses on the social networks of SNS users who are potential donors and regards these networks as an important factor in online charity-giving. In other words, we expect that participation in online-based donation campaigns differs depending on the level of SNS users’ social interaction. The findings can be used to suggest effective digital marketing strategies to improve the performance of an NGO’s online campaign.

Prior studies report a positive relationship between the use of SNS and social networks [

8]. That is, forming relationships through SNS is easy and does not incur costs [

8], and increasing the use of SNS enables users to form networks with various people [

9] and further to make their relationship more intimate [

10]. Surprisingly, however, little is known about what effects SNS users’ social networks have on online charity-giving behavior. We expect that this study can make up for the shortcomings of prior studies by positing the level of social interaction and empathy as the mechanisms of donation behaviors. For example, generally, the more interactions with other people a person maintains, the better and more opportunities that person has to understand and care about others’ situations, and this experience stirs feelings or empathy toward people in need. Thus, we can expect that the more and wider social networks the SNS user has, the more actively he or she will invite friends to participate in donation and the more donor participation will result. Here, empathy refers to a fundamental emotional factor which generates pro-social behaviors [

11,

12,

13]. When a person with empathy sees other people in difficult situations or in need, the person understands their situation and becomes sympathetic to their feelings, which arouses the willingness and behavior to help those in need. Therefore, we expect that SNS users’ social interaction has a positive effect on donation behavior, and this relationship is operated by the psychological mechanism of empathy.

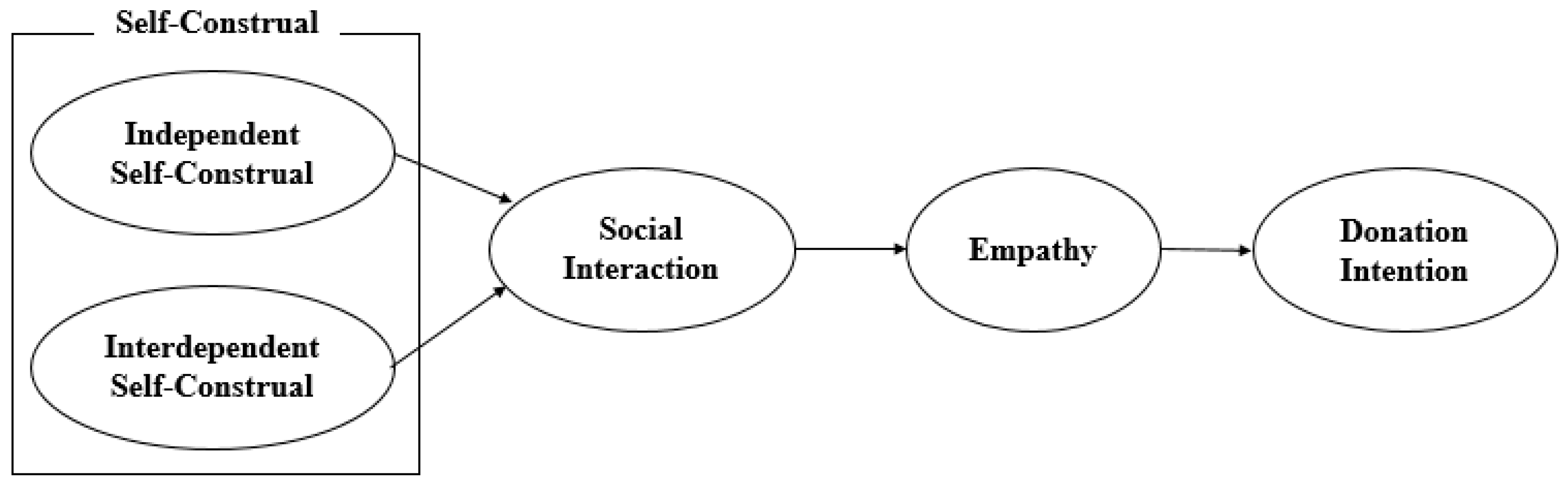

In addition, we use self-construal level theory as a lens to look into individual characteristics (independent self and interdependent self) as an antecedent variable affecting SNS users’ social interactions. Many prior studies using this theory have demonstrated that the interdependent self, which values interaction with family, friends and people around the self, better maintains social relationships than the independent self [

14,

15]. Therefore, SNS users with an interdependent disposition are expected to have broader interpersonal relationships online as they are good at social interactions, which results in increased donation behavior. On the other hand, an independent disposition is not expected to have a positive effect on interpersonal relationships online.

In the next section, we review the literature on SNS users’ social interactions, explore antecedent factors which affect interpersonal relationships based on self-construal level theory and develop a research model by predicting relationships among social interaction, empathy and online donation behavior. We also use structural equation modeling to analyze data collected through online surveys to verify the hypotheses and the research model. Finally, we summarize the study findings and discuss the implications and limitations of this study.

2. Theory and Hypothesis

Prior studies on offline-based donations have investigated the effect of various determinants (e.g., image and brand power of charity organization, demographic characteristics such as age, income, gender, and occupation, internal factors such as the individual’s sense of justice and compassion, previous experience of donation) on donation behaviors [

16]. On the other hand, prior studies on online donation conceptually explain the interaction between the companies hosting online campaigns and the participants [

17], and rarely conduct empirical studies on the factors affecting donation intention. The empirical studies that have been conducted mainly verify that marketing input factors of the organizations which plan and perform online donations can affect donation behaviors. For example, the aesthetics of an online campaign site or the quantity and quality of information obtained through the website have a positive effect on donation intentions [

18], and an online system with quick and easy (efficient) delivery of information can stimulate donation intentions since potential online donors have a high level of need for information about the use of their donations [

19]. However, empirical studies on the relationship between the characteristics of participants in online campaigns and their donation behaviors are difficult to find. This study focuses specifically on participants’ characteristics related to online media (online social relationships).

2.1. Online Social Interaction

Early internet studies suggested that interpersonal relationships built through the medium of the internet are insincere, impersonal and even hostile [

20,

21]. However, these early studies mainly explored how interpersonal relationships were formed through the Internet in laboratory settings and showed that face-to-face situations was more effective for problem-solving tasks than the internet situations [

22]. Many of these studies concluded that it is difficult to form deep and serious interpersonal relationships on the internet [

23,

24,

25].

More recent studies suggest a different view on the formation of interpersonal relationships through the internet; although desirable relationships are not formed by a short-term experiment, it is possible to form a meaningful relationship if an online relationship is maintained in the long run. That is, it is possible to form a good human relationship through the Internet in the long term although the formation of the relationship is delayed. Meta-analyses of studies on computer-mediated communication demonstrate that socio-emotional communication is found more frequently in conversations over the Internet than in face-to-face conversations in the long term [

26]. In addition, it has been found that interpersonal relationships can be formed on the internet which share intimacy and emotional sympathy although the internet cannot help people to meet directly [

27,

28,

29]. Online game users say they have deeper relationships with the people they play with online than with people they meet in real life, and members of a church mentioned that they know people who interact on the church’s website better than their closest friends [

30]. In addition, more dialogues are conducted with people and more friendships are formed by the use of the internet [

31]. There is also a view that the internet helps people to build new and meaningful interpersonal relationships beyond the geographical limitations of physical distance [

32].

Many studies on internet activities and formation of online relationships have reported that the level of internet activity has a positive effect on interpersonal relationships [

33]. As the duration of activity in an online community and the level of participation in the community increase, emotional attachment in online interpersonal relationships also increases [

33]. In addition, the more communication one has through online messaging systems, the greater the emotional bond and the more intimate feeling one has with the other party. These findings suggest that people who are active on the internet for a long time and interact with different people can form deep and varied interpersonal relationships on the internet.

2.2. Self-Construal Level Theory and Social Interaction

Interpersonal relationships develop based on deep and intimate social interaction [

34], but these relationships differ depending on the level of interdependence [

33].

“Self-construal level is a collective concept of an individual’s thoughts, emotions and behaviors in such a way that one individual is considered as independent or as associated with other people" [

19]. Self-construal may be independent, which regards oneself as an independent being separate from others, or interdependent, which regards oneself as a connected entity rather than being separate from others [

35]. People with independent self-construal seek independence and separation from others and emphasize individuality and uniqueness. Because they seek to achieve uniqueness and self-realization, they value individual thoughts, feelings and behaviors over anything else and are less responsive to social or interpersonal settings. On the other hand, a person with interdependent self-construal seeks to harmonize or assimilate with others and emphasizes connections and relationships. These people put parents, friends, colleagues or close friends before themselves [

14,

19].

Extending self-construal level theory to interpersonal relationships in the online context, individuals with independent self-construal maintain distance from specific groups and have low levels of social interaction in online networks due to their characteristic of pursuing a more independent and unique personality. By contrast, individuals with interdependent self-construal are expected to have positive and active social interactions in online networks due to their characteristic of valuing assimilation and bonding with others and desiring to show their orientation toward the group. Thus, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Interdependent self-construal has a positive effect on social interaction in online networks.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Independent self-construal has a negative effect on social interaction in online networks.

2.3. Social Interaction and Empathy

Positive emotions such as emotional support, empathy and sharing of pleasant experiences are vital in the process of forming and maintaining interpersonal relationships. Communication skills that enable one to actively deliver and accept what one wants to communicate are the beginning of interpersonal relationships and understanding toward others empowers one to form desirable interpersonal relationships [

36]. Barnes [

37] demonstrated that understanding and sharing empathy with others can be possible based on positive interpersonal interactions, which implies that empathy toward and understanding of the other party are the basic emotions which form and maintain social interaction.

A sizable body of research on the association between interpersonal relationships and empathy has verified a positive relationship between the two [

12,

38,

39]. Empathy is defined as an emotional bond which enables one to identify with what the other party feels and thinks. Without empathy, it is impossible to convey one’s mind to the other party and it is also difficult to understand the thoughts and actions of the other party [

40]. In particular, empathy effectively maintains interpersonal relationships and includes the ability to think, feel and communicate in an appropriate manner [

41].

Online social interaction also has an important effect on emotion. That is, online interpersonal relationships affect an individual’s positive emotion and help the individual maintain a positive emotional state [

42]. Thus, we can predict that online social interaction has a positive effect on empathy, which enables one to feel the emotions of the other party:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Social interaction in online networks has a positive effect on empathy.

2.4. Empathy and Prosocial Behavior

Many studies show that empathy is related with helping behavior [

38,

43,

44,

45]. According to the empathy-altruism hypothesis (EAH), empathy induces altruistic motivation, and its ultimate goal is to protect or enhance the welfare of the other person with whom one feels empathy [

43]. Prior studies on helping behavior refer to empathy and sympathy as the most frequent motivators for donors [

43,

46]. Most people extend a helping hand more quickly when they feel a stronger emotional pain toward the needy [

38,

47]. This pain decreases more quickly and they feel better when they help than when they do not. Hence, in order for the donation campaigns to be more effective, it is important to draw out a high level of empathy from the donors for the beneficiaries [

12,

48]. A recent study on SNS users confirmed that the simple act of writing with empathy for the other party improves prosocial behaviors. Therefore, we expect that empathy positively affects donation intention and serves as a psychological mechanism to explain the relationship between social interaction and donation intention. The hypothesis is presented as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Empathy has a positive effect on online donation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings and Implications

As mentioned in the introduction, the rapidly growing digital market has a great impact on NGO donation campaigns. This study, based on various previous studies on consumer behavior in digital markets, assumes that consumers’ construal levels are expressed in the digital market (social interaction online) and that these consumers’ characteristics affect individuals’ donation intent. In other words, this study makes the first theoretical contribution to expanding the research spectrum of digital markets from general offerings (products and services that are provided from commercial enterprises) to products emphasizing social sustainability through donations.

This study investigated the types of people who are willing to make donations in an online donation environment and what characteristics they have. The results show that donation participation increases with increased online social interaction and that the relationship between social interaction and donation intention is mediated by the psychological mechanism of empathy. Although social interaction, empathy and donation intention have been studied in various research areas, little research on these topics has been conducted in the online setting. That is, the results of SNS users’ donation behavior demonstrated in this study are very new findings and are expected to broaden the range of online donation research. These findings have the additional theoretical contribution of broadening the spectrum of diverse research on sustainable societies. In particular, the findings of this study offer the following theoretical implications:

First, we investigated donors’ characteristics to confirm the characteristics of people who have more social interactions. Based on the self-construal level theory, we classified users as having an interdependent self and independent self and investigated the effect of each characteristic on online social interaction. The interdependent self values relationships with people and tries to form and maintain diverse relationships with various people. This characteristic plays a positive role in online social interactions as well as in face-to-face relationships. However, our results also reject the hypothesis of a negative effect of the independent self on social interactions. A possible explanation for this is cultural influences. Many Eastern countries such as China, Japan and Korea represent highly collectivistic cultures, where an interdependent self-view prevails. In such cultures, harmony and relatedness are more important than individual uniqueness [

66]. In other words, although we measured survey participants’ self-construal tendency and divided it into an independent self and interdependent self for analysis, we did not rule out the influence of collectivist culture. This collectivist influence combined with the effect of interdependent self may render the effect on online social interaction insignificant.

Second, through additional analysis, this study settles the problem of using consequent variables raised by a recent study on donation behavior [

56]. The research model of this study has even more significant meaning as a donation behavior decision model of online donors as it confirmed that the results of the study when donation intention is used as the consequent variable are not different from those when the donation amount is used as the consequent variable.

Next, empirically, this study shows the need for NGOs to understand potential donors as a sort of consumer and approach them strategically in order to develop a successful online campaign. Specifically, the findings of this study offer the following empirical implications:

First, this study investigated the characteristics of potential donors participating in online donation campaigns. We identified behavioral characteristics of potential donors in online fundraising activities by examining whether those who are active in online social interactions such as SNS activities or online communities participate more in online donations. We expect that users who interact with many people online are leaders of communities or power users who exert significant influence through SNS. As mentioned above, online fundraising campaigns are conducted through peer-to-peer channels such as SNS. Therefore, if practitioners and nonprofit organizations involved in fundraising activities target online influencers in an appropriate manner, these people can be expected to invite their friends to more actively participate, resulting in more donations.

Second, this study investigated the psychological mechanisms of donors who participate in online fundraising. Prior studies have demonstrated that prosocial behaviors are caused by emotions such as empathy and sympathy for beneficiaries. We confirmed that donor empathy works as a psychological mechanism to increase donation participation in the online environment as well. Empathy is one of the factors that best explains altruism as the donor’s emotional response to the beneficiaries. People are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors such as donations when they are highly empathetic with other people [

43,

49,

52]. Hence, in order to promote participation in donation campaigns, it is vital to draw out a high level of donors’ empathy with beneficiaries.

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the findings of this study rejected the hypothesis of a negative effect between independent self-construal and social interaction. This may be due to the dominant collectivist tendency emphasizing relations in the Eastern culture to which the survey participants belong. Future researchers should distinguish and verify individual tendencies and cultural differences more precisely.

Second, academic studies on the relationship between age and donation have contradictory results; some have found that age has a positive effect on donation experience or donation levels [

67,

68,

69], while others found an inconsistent effect on donations [

70,

71,

72]. Thus, we suppose that it is difficult to apply the results of this study to all age groups. In particular, the Millennial generation has different preferences for making donations than the Baby Boomer generation. While 39% of Millennials prefer to make donation via social media, only 19% of Baby Boomers do [

7]. In addition, prior studies on donations have demonstrated that while donor characteristics such as income, occupation, and education level can have an effect on donation behaviors, their results are not consistent. Thus, studies on the relationship between various demographic variables such as donors’ age, gender, income, occupation, and education level and online donation are deemed to be an important follow-up task in the future.

Third, while donors show differential donation behavior based on demographic characteristics such as age, income and religion, they also engage in donation behavior spurred by external motivation such as tax benefits or solicitations or requests from people around them as well as by internal motivations such as empathy and sympathy [

43]. Although this study is limited to a psychological mechanism, it is also possible that external motivations such as recommendations from others and social evaluation due to the nature of online donation will have an effect. Future researchers could provide practical implications if they take into account the multifarious aspects of online donation motivation.

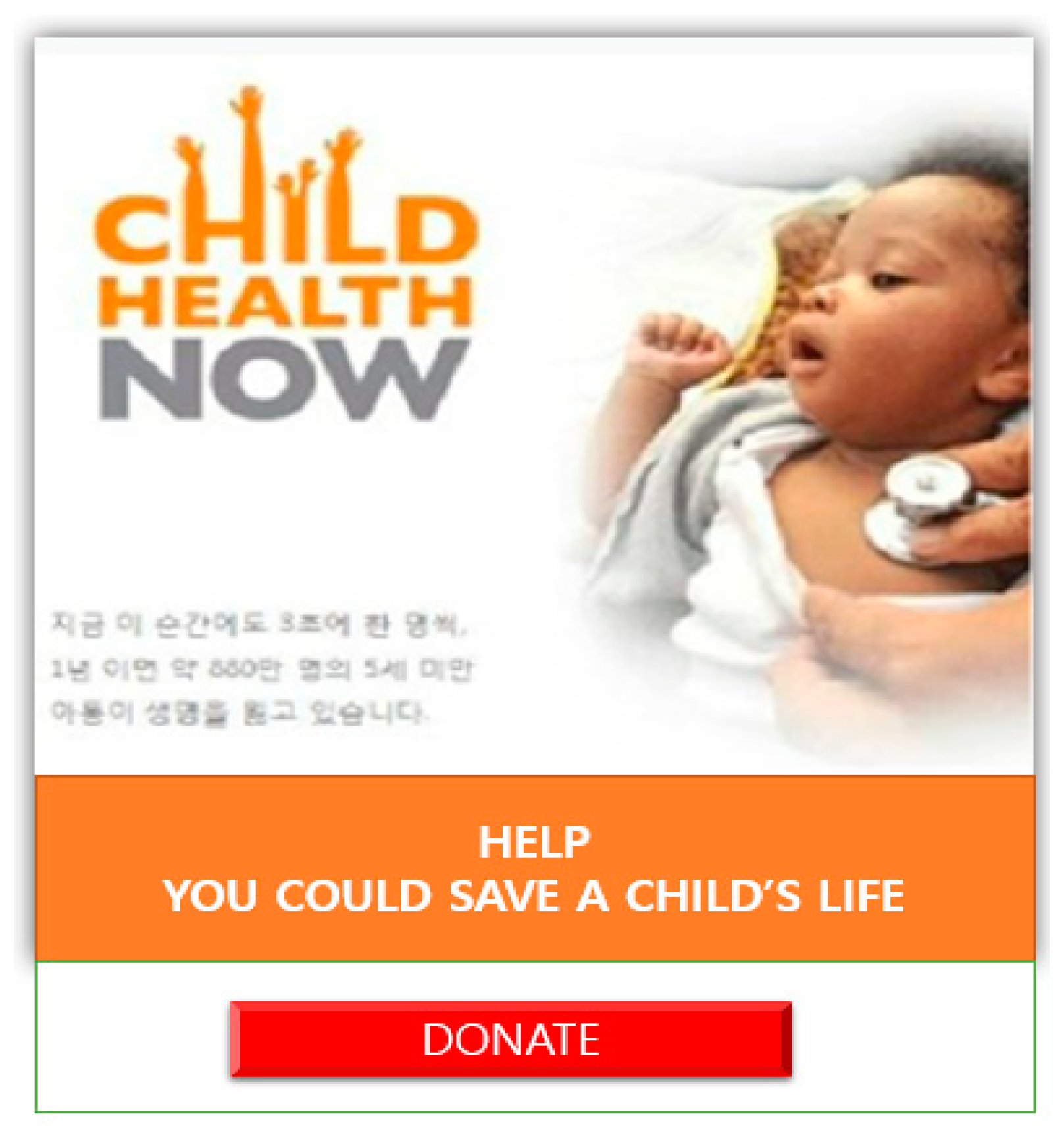

Finally, this study used a survey method in a strictly controlled environment to clarify the causal relationship. Although the online donation advertisement used as the stimulus in this study was similar to a real advertisement, caution is necessary in concluding whether survey participants in a virtual environment would make the same donation decisions in a real online donation campaign. In a real-world setting, we may not obtain the same results depending on participants’ available spending budget, past donation experience and so on. To overcome these limitations, future researchers should consider the influence of various variables using actual field data.