ICT and the Sustainability of World Heritage Sites. Analysis of Senior Citizens’ Use of Tourism Apps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Apps in Destination Marketing and Communication Strategies

2.2. The Cultural Tourist and World Heritage Sites

- Q1. What role do RICTs and, specifically, tourism apps play in the cultural tourist trip (choice, planning, etc.) of senior citizens?

- Q2. To what extent do RICT and, specifically, tourism apps determine the perception of the experience resulting of the cultural tourism trip of senior citizens?

- Q3. Do the tourism apps of the Spanish World Cultural Heritage Sites (WCHS) meet the expectations of senior cultural tourists (in terms of features and functions)?

- O1. Describe the use senior citizens make of RICT and, particularly, of tourism apps in the stages of selection, planning, booking, buying, and visit of the tourist destination.

- O2. Determine the incidence of RICT and, particularly, of tourism apps in the final perception of the experience resulting from the tourist trip.

- O3. Identify the expectations of senior tourists with regards to tourism apps.

- O4. Analyze a sample of tourism apps developed for WCHS.

- O5. Compare the expectations of cultural tourists with the features and functions of the selected tourism apps.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Data Collection

3.1.1. Qualitative Analysis

- The tourist profile of the focus group participants (the role they play in the selection and planning of the trip, preferred destinations, etc.).

- The relationship of tourists with RICT and tourism apps. To this end, we examined the online and offline sources and resources that they use in the different phases of the tourist journey (before, during, and after) and analyzed the expectations of the target regarding the features and functions of apps that can improve the tourist experience.

3.1.2. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Sample Profile

3.2.1. Qualitative Analysis

- -

- Focus group 1:

- ▪

- Five women aged 60, 63, 73, 76, and 86

- ▪

- Four men aged 60, 63, 65, and 75

- -

- Focus group 2:

- ▪

- Four women aged 62, 74, 77, and 82

- ▪

- Five men aged 60, 64, 66, 75, and 77

- -

- Focus group 3:

- ▪

- Four women aged 62, 66, 71, and 75

- ▪

- Three men aged 63, 68, and 72

3.2.2. Quantitative Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Senior Tourists (60 and Over), Relational, Information, and Communication Technologies (RICT), and Tourism Apps

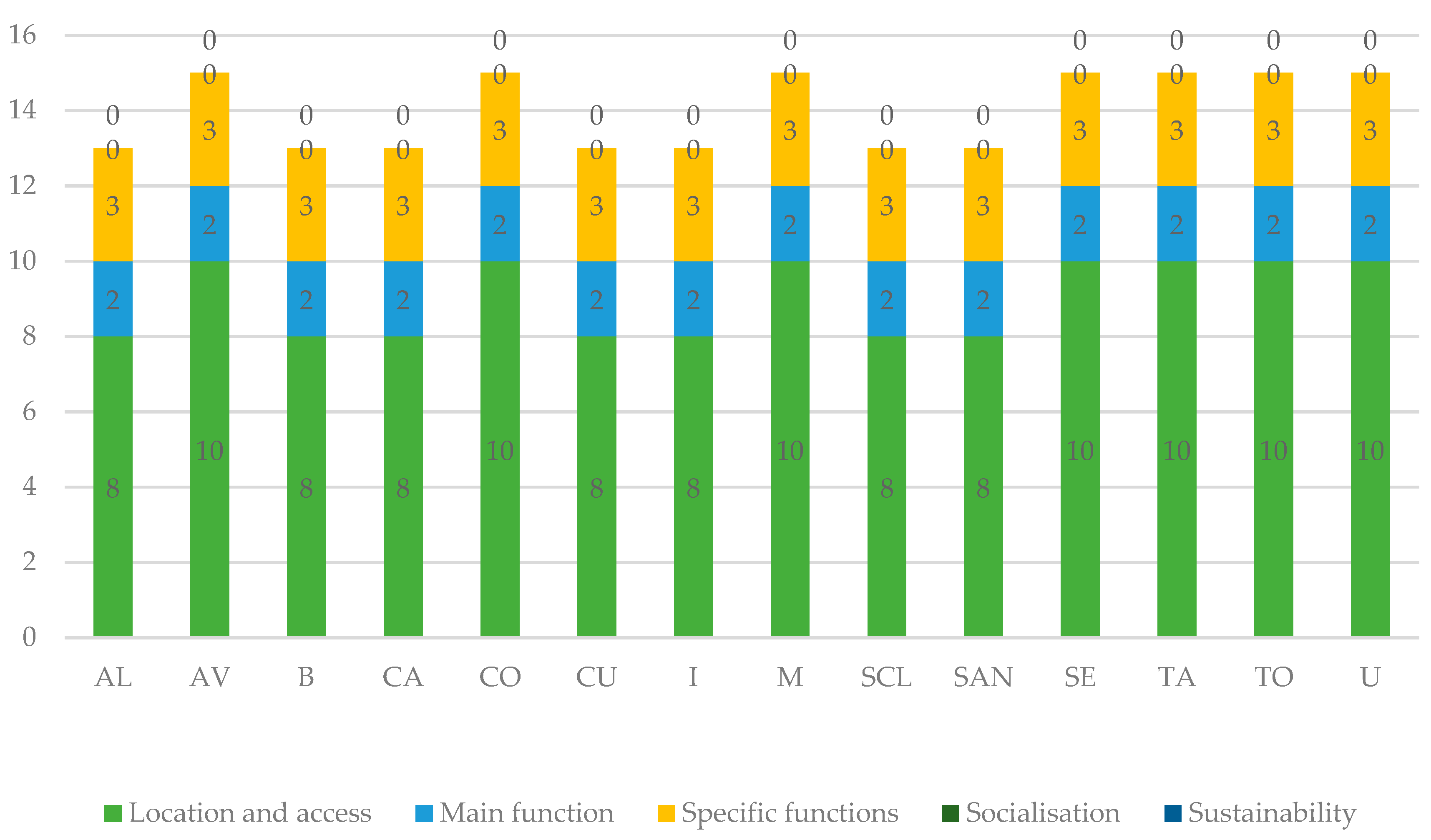

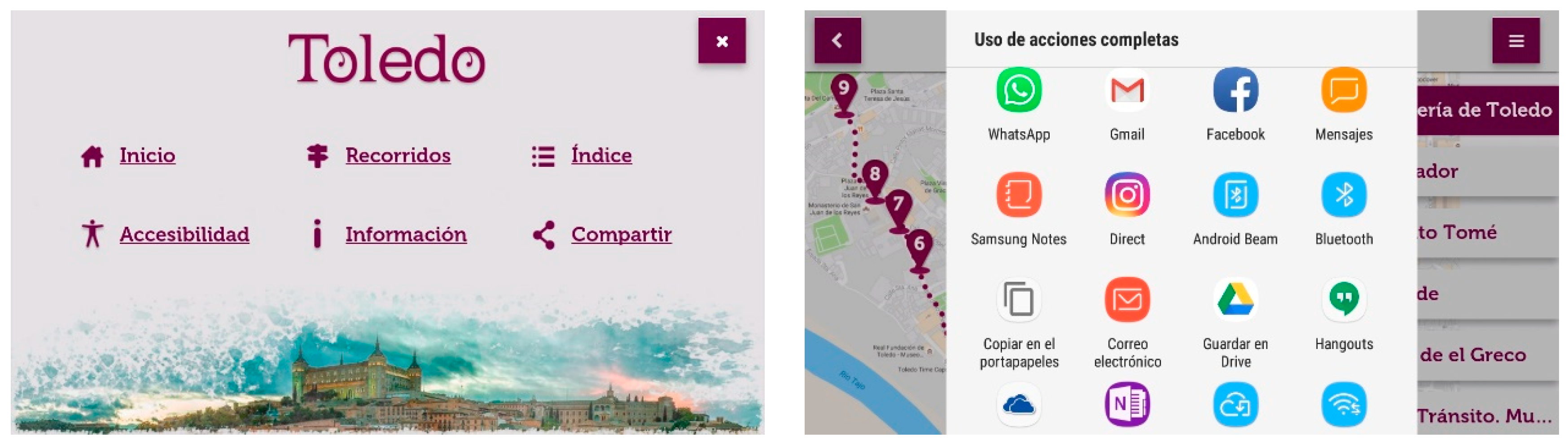

4.2. Analysis of Apps: Features and Functions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameters and Indicators | Description and Analysis Items | Rating Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Location and access | ||

| Location on the Website of the SWHC | Is the app easily located? The assessment focuses on whether the corporate website of the SWHC includes links to the app and whether these links are accessible and usable | |

| Is there a to download the app on the website? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Is the link easily located on the website? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Is the link operational? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Location on the Website of WCHS | Is the app easily located? The assessment focuses on whether the institutional tourism websites includes links to the app of their respective destinations and whether these links are accessible and usable. | |

| Is the link easily located on the website? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Is the link operational? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Suitability of the Name | Does the name of the app contribute to the easy and quick identification of the brand? A suitable name does not use acronyms, diminutives, or other formulas that can cause confusion in the user. | No: 0/Yes: 1 |

| Versions and Adaptation | For what systems is the app available? Apps must be developed to be run on the main operating systems | |

| App Store. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Google Play. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Other (specify). | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Free or Paid | Can the app be downloaded and used in full free of charge or does it include payment features or has a paid version (freemium), or is it a paid app (specify the cost) | Free: 2/Freemium: 1/Payment: 0 |

| Global rating of location and access: the previous results are added | ||

| Main Function | This section evaluates the main function of the app | |

| Planning: mainly provides information about the destination (text content, graphic materials, etc.). Pre-travel | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Action: allows the user to search, arrive, buy, etc. On-travel. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Dissemination: Is it used to disseminate and share the experience. On and Post-travel | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Overall rating of the main function: the previous results are added | ||

| Specific Functions | This section evaluates whether the app offers the general functions well valued by users in general and tourists in particular | |

| Information (agenda, resources, etc.) | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Tourist guides | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Entertainment (games). | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Internal user-user interactivity: web-based content generation (comments, ratings, etc.) | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| External user-user interactivity: web-based content generation (comments, ratings, etc.) | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Internal user-admin interactivity: communication channels with the app developers (consultations, ratings, comments, etc.). | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Image gallery | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Geolocation. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Online reservation: does the app allow the user to book products and services online? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Online payment. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Does the app support more than one form of online payment (credit card, PayPal, etc.)? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Other (Specify). | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Overall rating of specific functions: the previous results are added | ||

| Socialisation | This section evaluates the capacity of the app to enable users to establish relationships with other users | |

| Does the application offer access to social networks? | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| If the answer to the previous question is YES, specify the social networks supported: | ||

| Whatsapp. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Facebook. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| YouTube. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Instagram. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Twitter. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Spotify | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| LinkedIn. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Pinterest. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| TripAdvisor. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Foursquare. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Minube. | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Other (Specify). | No: 0/Yes: 1 | |

| Overall rating of socialisation: the previous results are added | ||

| Sustainability | This section evaluates whether the app provides information and advice that aim to contribute to the care and preservation of cultural heritage. | No: 0/Yes: 1 |

References

- Gómez Oliva, A.; Server Gómez, M.; Jara, A.J.; Parra-Meroño, M.C. Turismo inteligente y patrimonio cultural: un sector a explorar en el desarrollo de las Smart Cities. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 389–411. [Google Scholar]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Baggio, R. Knowledge transfer in smart tourism destinations: Analyzing the effects of a network structure. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interactive Advertising Bureau. Estudio Anual Mobile Marketing 2017. 2017. Available online: https://iabspain.es/wp-content/uploads/estudio-mobile-2017-vcorta.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Martín-Sánchez, M.; Miguel-Dávila, J.A.; López-Berzosa, D. Turitec 2012: IX Congreso nacional turismo y tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones. In M-tourism: las apps en el sector turístico; Universidad de Málaga (UMA), Escuela Universitaria de Turismo: Málaga, Spain, 2012; pp. 407–424. ISBN 978-84-608-0787-2. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rodríguez, L.M.; Torres-Toukoumidis, A.; Aguaded, I. Incidencia de las aplicaciones móviles en la toma de decisiones del potencial turista: Caso Huelva capital. adComunica 2016, 12, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Palos-Sánchez, P.; Reyes-Menéndez, A. Marketing a través de aplicaciones móviles de turismo (m-tourism). Un estudio exploratorio International Journal of World Tourism. Int. J. World Tour. 2017, 4, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira Soares, A.L.; Mendes-Filho, L.; Barbosa Cacho, A.N. Evaluación de la información de una aplicación turística. Un análisis realizado por profesionales del turismo sobre la e-Guía Find Natal (Brasil). Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2017, 26, 884–904. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pino Romero, C.; CastellóMartínez, A.; Ramos-Soler, I. La comunicación en Cambio Constante. Branded Content, Community Management, Comunicación 2.0 y Estrategia en Medios Sociales; Fragua: Madrid, Spain, 2013; ISBN 978-84-70745-47-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sala, A.M.; Monserrat-Gauchi, J.; Campillo Alhama, C. The relational paradigm in the strategies used by destination marketing organizations. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2017, 72, 374–396. [Google Scholar]

- Marta-Lazo, C.; Gabelas, J.A. Comunicación Digital: un Modelo Basado en el Factor Relacional; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-91164-72-2. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, J.L.; Luque, A.; Zayas, B. Nuevas tecnologías para la interpretación y promoción de los recursos turísticos culturales. Pasos 2015, 13, 931–945. [Google Scholar]

- Galmés Cerezo, M. Comunicación y marketing experiencial: Aproximación al estado de la cuestión. Opción 2015, 31, 974–999. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sala, A.M.; Cifuentes Albeza, R.; Martínez-Cano, F.J. Las redes sociales de las organizaciones de marketing de destinos turísticos como posible fuente de eWOM. OBS* 2018, 3, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Chuckert, M.; Law, R.; Masiero, L. The relevance of mobile tourism and information technology: an analysis of recent trends and future research directions. J. Travel & Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 732–748. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, C.; Wang, R. Design and performance attributes driving mobile travel application engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuska, M.; Augustynska, B.; Mikolajewska, E.; Mikolajewski, D. M-tourism as increasing trend within current tourism and recreation - Polish and international experience. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1906, 180009. [Google Scholar]

- Campillo Alhama, C.; Martínez-Sala, A.M. La estrategia de marketing turístico de los Sitios Patrimonio Mundial a través de los eventos 2.0. Pasos 2019, 17, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sala, A.M. Marketing 2.0 applied to the tourism sector: the commercial function of the websites of destination marketing organization. Vivat Acad. 2018, 143, 01–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Meroño, M.C.; Beltrán-Bueno, M.A. Estrategias de Marketing para Destinos Turísticos; Eumed Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-16874-29-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lerario, A.; Varasano, A.; Di Turi, S.; Nicola Maiellaro, N. Smart Tirana. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhong, D. Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O.; Rabjohn, N. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth: The adoption of online opinions in online customer communities. Internet Res. 2008, 18, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Kim, Y. Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, E.; González, Y. Patrimonio cultural y turismo: oportunidades y desafíos de la valorización turística del patrimonio. 2018. Available online: http://www.aept.org/archivos/documentos/informe_patrimonio_ostelea18.pdf (accessed on 27 july 2018).

- Mondéjar Jiménez, J.A.; Cordente Rodríguez, M.; Mondéjar Jiménez, J.; Meseguer Santamaría, M.L. Perfil del turista cultural: una aproximación a través de sus motivaciones. Her. Mus. 2009, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, P.; Galindo, N. Perfil del turista cultural en ciudades patrimoniales. Los casos de San Cristóbal de la Laguna y Córdoba (España). Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2015, 1, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Interactive Advertising Bureau. Estudio Anual de Redes Sociales 2018. 2018. Available online: https://iabspain.es/wp-content/uploads/estudio-redes-sociales-2018_vreducida.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Sherman, L.E.; Greenfield, P.M.; Hernandez, L.M.; Dapretto, M. Peer Influence Via Instagram: Effects on Brain and Behavior in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Passiante, G. Is tourism a driver for smart specialization? Evidence from Apulia, an Italian region with a tourism vocation. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.D.; Goo, J.; Nam, K.; Yoo, C.W. Smart tourism technologies in travel planning: The role of exploration and exploitation. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.C.; Chung, N.; Gretzel, U.; Koo, C. Constructivist Research in Smart Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 25, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Duan, L. The concept of smart tourism in the context of tourism information services. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen. Estilos de Vida Generacionales. 2015. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/latam/docs/reports/2016/EstilosdeVidaGeneracionales.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2018).

- González Oñate, C.; Fanjul Peyró, C. Aplicaciones móviles para personas mayores: un estudio sobre su estrategia actual. Aula Abierta 2018, 47, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Sobre Equipamiento y uso de TecnologíAs de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares. 2019. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176741&menu=resultados&idp=1254735976608 (accessed on 23 February 2019).

- McCann WorldGroup. Truth about Age. 2017. Available online: http://www.mccann.es/assets/contenidos/casos_estudio/2s7S7_TAA_Executive_Summary_short.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2019).

- Ramos-Soler, I. El estilo de Vida de los Mayores y la Publicidad; Obra Social, Fundación “La Caixa”: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-84-76649-53-4. [Google Scholar]

- Losada Sánchez, N.; Alén González, E.; Dominguez Vila, T. Factores explicativos de las barreras percibidas para viajar de los senior. Pasos 2018, 16, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano Benítez, V.; Marín-Gutiérrez, I.; Ordóñez González, K. Comunicación turística 2.0 en Ecuador. Análisis de las empresas públicas y privadas. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 633–647. [Google Scholar]

- Túñez López, M.; Altamirano, V.; Valarezo, K.P. Comunicación turística colaborativa 2.0: promoción, difusión e interactividad en las webs gubernamentales de Iberoamérica. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2016, 71, 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Campillo Alhama, C. El desarrollo de políticas estratégicas turísticas a través de la marca acontecimiento en el municipio de Elche (2000-2010). Pasos 2012, 10, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Lanuza, A.; Pulido Fernández, J.I. El impacto del turismo en los Sitios Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Una revisión de las publicaciones científicas de la base de datos Scopus. Pasos 2015, 13, 1247–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negruşa, A.; Toader, V.; Rus, R.; Cosma, S. Study of Perceptions on Cultural Events’ Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Fernández, J.I.; López Sánchez, Y. Propuesta de contenidos para una política turística sostenible en España. Pasos 2013, 11, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Riganti, P.; Wang, J. Tourism, cultural heritage and e-services: Using focus groups to assess consumer preferences. Tourismos 2012, 7, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S. The Role of Mobile Technology in Tourism: Patents, Articles, News, and Mobile Tour App Reviews. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO/UBC Vancouver Declaration. The Memory of the World in the Digital Age: Digitization and Preservation. 2012. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/mow/unesco_ubc_vancouver_declaration_en.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2018).

- Gretzel, U.; Koo, C.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z. Special issue on smart tourism: convergence of information technologies, experiences, and theories. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cavia, J.; López, M. Communication, destination brands and mobile applications. Comm. Soc. 2013, 26, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Corallo, A.; Trono, A.; Fortunato, L.; Pettinato, F.; Schina, L. Cultural Event Management and Urban e-Planning Through Bottom-Up User Participation. Int. J. Plan. Res. 2018, 7, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Murphy, L. There is no such thing as sustainable tourism: Re-conceptualizing tourism as a tool for sustainability. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2538–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collan, M.; Sell, A.; Anckar, B.; Harkke, V. Approaches to Using e- and m-Business Components in Companies; Turku Centre for Computer Science: Turku, Finland, 2005; ISBN 978-95-21215-0-87. [Google Scholar]

- Sziva, I.; Zoltay, R.A. How attractive can Cultural Landscapes be for Generation Y? Almatourism 2016, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Bueno, M.A.; Parra-Meroño, M.C. Tourist profiles on the basis of motivation for traveling. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 607–609. [Google Scholar]

- Simonato, F.R.; Ariel Mori, M.; Los Millenials y las Redes Sociales. Estudio del Comportamiento, Ideología, Personalidad y Estilos de Vida de los Estudiantes de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata a Través del Análisis Clúster. C. Admin. 2015. Available online: https://revistas.unlp.edu.ar/CADM/article/view/1129 (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Ayala García, A.; Abellán García, A. La brecha digital continúa reduciéndose. Blog Envejecimiento [en-red]. 2017. Available online: https://envejecimientoenred.wordpress.com/2017/10/06/la-brecha-digital-continua-reduciendose/ (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Turismo de Residentes. 2018. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=12448 (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Movimientos turísticos en fronteras. 2018. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=13864 (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, P. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw-Hill Education: México, Mexico, 2014; ISBN 978-14-56223-96-0. [Google Scholar]

- Batthyány, K.; Cabrera, M. Metodología de la Investigación en Ciencias Sociales; Universidad de la República: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2011; ISBN 978-9974-0-0769-7. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Uma Introdução à Pesquisa Qualitativa; Bookman: Poôrto Alegre, Brazil, 2004; ISBN 978-85-36304-14-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, M.M.F.; Zouain, D.M. Pesquisa Qualitativa em Administração; FGV: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004; ISBN 978-85-22504-72-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Algarra, P.; Anguera, M.T. Qualitative/quantitative integration in the inductive observational study of interactive behaviour: impact of recording and coding among predominating perspectives. Qual. Quan. 2013, 47, 1237–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.M.; Ismail, R.; Fabil, N.; Norwawi, N.M.; Wahid, F.A. Measuring Usability: Importance Attributes for Mobile Applications. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 4738–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.M.; Gutiérrez, J. Métodos y Técnicas Cualitativas de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales; Editorial Sintesis: Madrid, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-84-77382-26-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, B.A. Grupo Focal na Pesquisa em Ciências Sociais e Humanas; Líber Livro: Brasília, Brazil, 2005; ISBN 978-85-98843-11-7. [Google Scholar]

- Grande Esteban, I.; Abascal Fernández, E. Fundamentos y Técnicas de Investigación Comercial; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2003; ISBN 978-84-73563-65-9. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación. 20º Navegantes en la Red. 2018. Available online: http://download.aimc.es/aimc/ARtu5f4e/macro2017ppt.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Rodrigues, J.; Pocinho, R.; Belo, P.; Santos, G. Análisis del nivel de educación en participantes de turismo de tercera edad en Portugal. Rev. Lusófona Educ. 2017, 38, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditrendia Informe Mobile en España y en el Mundo 2017. 2018. Available online: https://www.amic.media/media/files/file_352_1289.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2018).

| Destination | App Name | Downloads | Rate (Average/5) 1/03/2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01/08/18 | 01/03/19 | |||

| Alcalá de Henares (AL) | Alcalá de Henares—Guía de turismo | +1000 | +1000 | 4.7 |

| Ávila (AV) | Avilla Turismo | +5000 | +5000 | 3.8 |

| Baeza (B) | Baeza—Guía de visita | +500 | +1000 | 4.2 |

| Cáceres (CA) | Cáceres | +1000 | +1000 | 4 |

| Córdoba (CO) | Córdoba—Guía de visita | +1000 | +1000 | 3 |

| Cuenca (CU) | Cuenca—Guía de visita | +1000 | +1000 | 4.1 |

| Ibiza (I) | Ibiza Ciudad | +100 | +100 | 4-1 |

| Mérida (M) | Mérida—Guía de visita | +1000 | +5000 | 3.6 |

| Salamanca (S) | Salamanca—Guía de visita | +1000 | - 1 | |

| San Cristóbal de la Laguna (SCL) (SCL) | San Cristóbal de la Laguna | +100 | +500 | 3.8 |

| Santiago de Compostela (SAN) | Santiago de Compostela | +1000 | +1000 | 4.8 |

| Segovia (SE) | Segovia para todos | +5000 | +5000 | 3.5 |

| Tarragona (TA) | Tarragona accesible | +1000 | +1000 | 3.7 |

| Toledo (TO) | Toledo | - 2 | +1000 | 3.5 |

| Úbeda (U) | Úbeda Turismo | +1000 | +1000 | 4.7 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos-Soler, I.; Martínez-Sala, A.-M.; Campillo-Alhama, C. ICT and the Sustainability of World Heritage Sites. Analysis of Senior Citizens’ Use of Tourism Apps. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113203

Ramos-Soler I, Martínez-Sala A-M, Campillo-Alhama C. ICT and the Sustainability of World Heritage Sites. Analysis of Senior Citizens’ Use of Tourism Apps. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113203

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos-Soler, Irene, Alba-María Martínez-Sala, and Concepción Campillo-Alhama. 2019. "ICT and the Sustainability of World Heritage Sites. Analysis of Senior Citizens’ Use of Tourism Apps" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113203

APA StyleRamos-Soler, I., Martínez-Sala, A.-M., & Campillo-Alhama, C. (2019). ICT and the Sustainability of World Heritage Sites. Analysis of Senior Citizens’ Use of Tourism Apps. Sustainability, 11(11), 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113203