Improving Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&A Sustainability in the Globalization Age—Research on Acquisition and Application of the Foreign Experience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Hypothesis Development

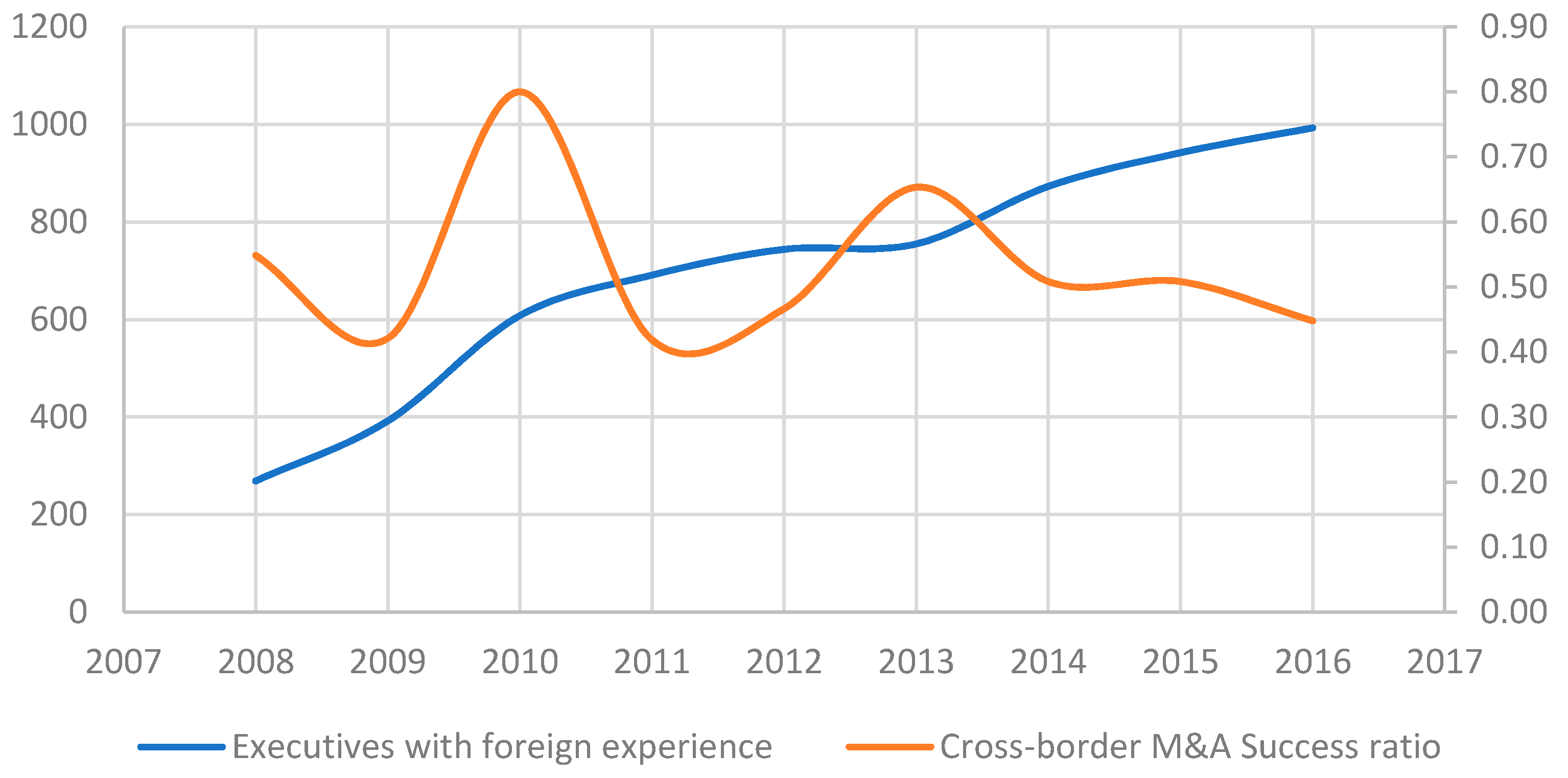

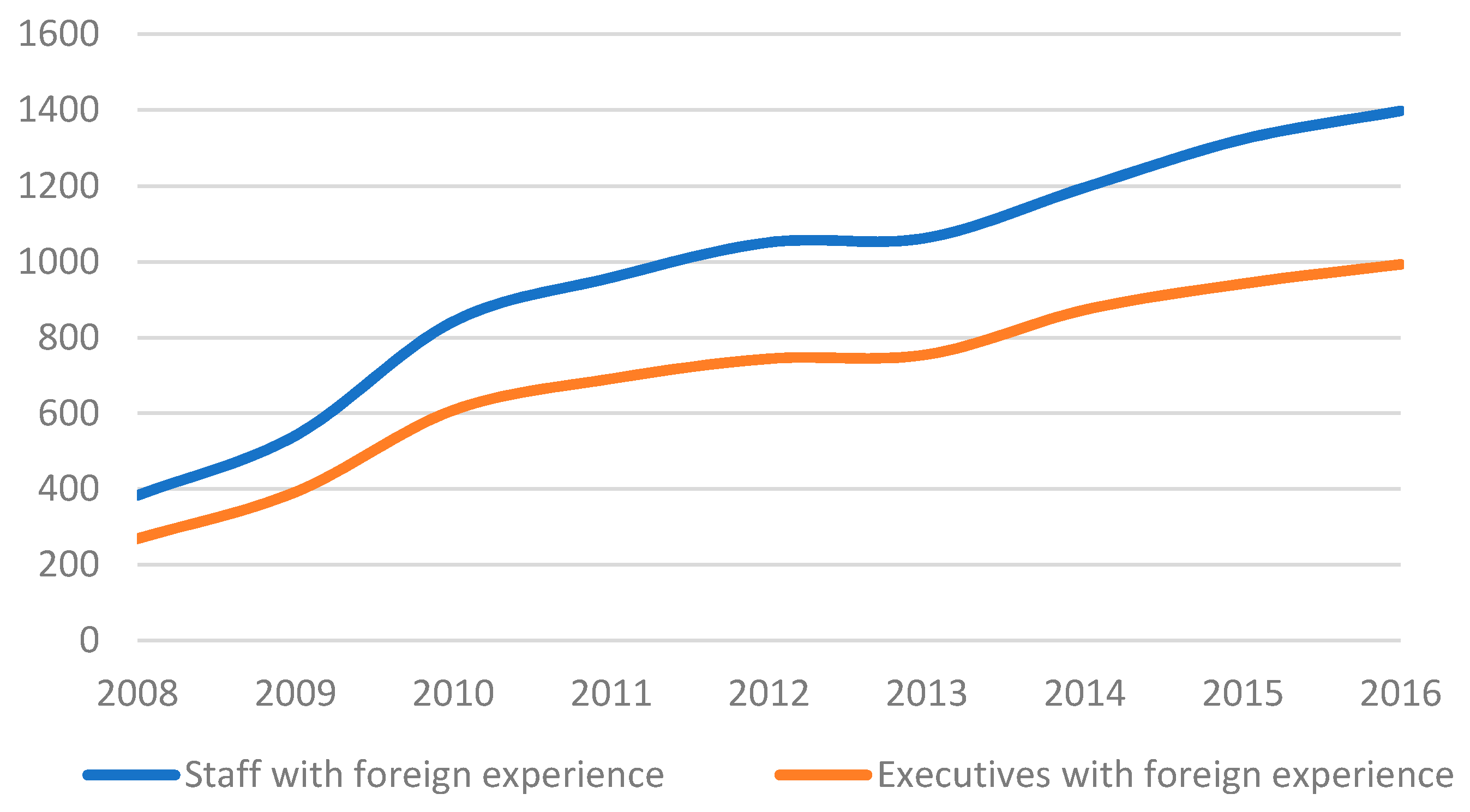

3.1. Foreign Experience and Cross-Border M&A Sustainability

3.2. Application of Experiential Knowledge: The Moderating Role of Executives’ Characteristics

3.2.1. Moderating Effect of Tenure

3.2.2. Moderating Effect of the Pay Gap

4. Methodology

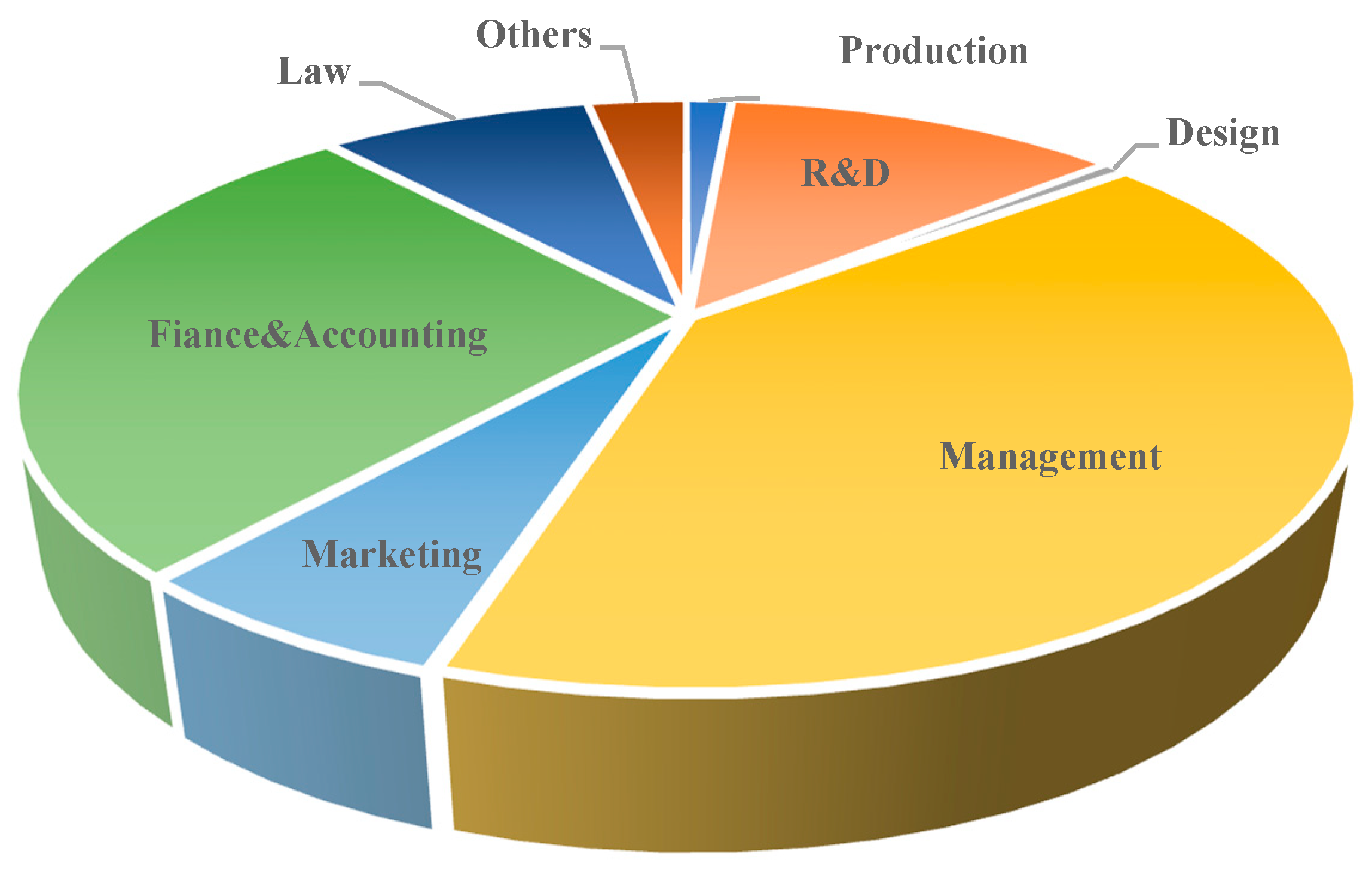

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Measures

5. Result and Findings

5.1. Regression Results

5.2. Further Analysis

5.3. Robustness Test

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, C. Cross-Border M&A and the Acquirers’ Innovation Performance: An Empirical Study in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1796. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, C.; Block, J.; Sandner, P. The impact of acquisitions on Chinese acquirers’ innovation performance: An empirical investigation of 1545 Chinese acquisitions. J. Bus. Econ. 2018, 2018, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Coping with the governance gap and improving cross-border governance of group companies. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2011, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Ma, X.; Tong, T.W.; Li, W. Network Information and Cross-Border M&A Activities. Glob. Strategy J. 2018, 8, 301–323. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, P.; Wang, B. The liability of opaqueness: State ownership and the likelihood of deal completion in international acquisitions by Chinese firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 40, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschi, P.X.; Métais, E. Do firms forget about their past acquisitions? Evidence from French acquisitions in the United States (1988–2006). J. Manag. 2013, 39, 469–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, M.L.A. When do firms learn from their acquisition experience? Evidence from 1990–1995. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.L.; Schmidt, D.R. Determinants of tender offer post-acquisition financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatotchev, L.; Liu, X.; Buck, T.; Wright, M. The export orientation and export performance of high-technology SMEs in emerging markets: The effects of knowledge transfer by returnee entrepreneurs. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Breznitz, D.; Murphree, M. Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high-tech industries. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.T.K.; Wie, Z. Rethinking the literature on the performance of Chinese multinational enterprises. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2016, 12, 269–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, A.; John, A.; Haque, M.Z.; Alice, H. A review of the internationalization of Chinese enterprises. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 2018, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Li, Y.; Meyer, K.E.; Li, Z. Leadership experience meets ownership structure: Returnee managers and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Manag. Int. Rev. 2014, 55, 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Li, W. Experience and success of Chinese Cross-border acquisitions: Moderating role of non-related experience and government factors. World Econ. Study 2015, 8, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. Liability of foreignness, organizational learning and realization of Chinese MNE’s cross-border M&A deals. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 39, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver, J.M.; Yeung, M.B. The effect of own-firm and other-firm experience on foreign direct investment survival in the United States, 1987–1992. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q. CEO tenure and ownership mode choice of Chinese firms: The moderating roles of managerial discretion. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.D.; Fredrickson, J.W. Top management team coordination needs and the CEO pay gap: A competitive test of economic and behavioral views. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 96–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bužavaitė, M.; Ščeulovs, D.; Korsakienė, R. Theoretical approach to the internationalization of SMEs: Future research prospects based on bibliometric analysis. Entrepreneurship Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1297–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čirjevskis, A. Acquisition based dynamic capabilities and reinvention of business models: Bridging two perspectives together. Entrepreneurship Sustain. Issues 2017, 4, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jory, S.R.; Ngo, T.N. Cross-border acquisitions of state-owned enterprises. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 1096–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B.B.; Hasan, I.; Sun, X. Financial market integration and the value of global diversification: Evidence for US acquirers in cross-border mergers and acquisitions. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohli, R.; Mann, B.J.S. Analyzing determinants of value creation in domestic and cross border acquisitions in India. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 998–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masulis, R.W.; Wang, C.; Xie, F. Globalizing the boardroom—The effects of foreign directors on corporate governance and firm performance. J. Account. Econ. 2012, 53, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.F.; Huang, Y.; Sun, G.S. Analysis of institutional factors influencing the cross-border M&A performance. Word Econ. Stud. 2015, 6, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, K.R.; Daminelli, D.; Fracassi, C. Lost in translation? The effect of cultural values on mergers around the world. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 117, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Makhija, A.K.; Shenkar, O. The asymmetric relationship between national cultural distance and target premiums in cross-border M&A. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, R.; Mann, B.J.S. Analyzing the likelihood and the impact of earnout offers on acquiring company wealth gains in India. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2013, 16, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemerling, J.; Michael, D.; Michaelis, H. China’s Global Challengers: The Strategic Implications of Chinese Outbound M&A; Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Luedi, T. China’s track record in M&A. McKinsey Q. 2008, 3, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Klossek, A.; Linke, B.M.; Nippa, M. Chinese enterprises in Germany: Establishment modes and strategies to mitigate the liability of foreignness. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Harrison, J.S.; Ireland, R.D. Mergers and Acquisitions: A Guide to Creating Value for Stakeholders; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.; Haleblian, J. Understanding acquisition performance: The role of transfer effects. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadolska, A.; Barkema, H.G. Learning to internationalise: The pace and success of foreign acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 1170–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, G.; Schijven, M. How do firms learn to make acquisitions? A review of past research and an agenda for the future. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 594–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschi, P.X.; Métais, E. International acquisition performance and experience: A resource-based view. Evidence from French acquisitions in the United States (1988–2004). J. Int. Manag. 2006, 12, 430–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.J.; Caves, R.E. Uncertain outcomes of foreign investment: Determinants of the dispersion of profits after large acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleblian, J.; Finkelstein, S. The influence of organizational acquisition experience on acquisition performance: A behavioral learning perspective. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wright, M.; Filatotchev, I.; Dai, O.; Lu, J. Human mobility and international knowledge spillovers: Evidence from high-tech small and medium enterprises in an emerging market. Strateg. Entrepreneurship J. 2010, 4, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambharya, R.B. Foreign experience of top management teams and international diversification strategies of U.S. multinational corporations. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Fredrickson, J.W. Top management teams, global strategic posture, and the moderating role of uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 533–545. [Google Scholar]

- Ahammad, M.F.; Glaister, K.W. The pre-acquisition evaluation of target firms and cross border acquisition performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E.; Bell, M. The micro-determinants of meso-level learning and innovation: Evidence from a Chilean wine cluster. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, A.; Fosfuri, A.; Tribó, J.A. Managing external knowledge flows: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.C.; Meyer, K.E. Business groups’ outward FDI: A managerial resources perspective. J. Int. Manag. 2010, 16, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Pollock, T.G.; Leary, M.M. Testing a model of reasoned risk-taking: Governance, the experience of principals and agents, and global strategy in high-technology IPO Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, P.; Datta, D.K. CEO successor characteristics and the choice of foreign market entry mode: An empirical study. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikhani, A. A note on the criticisms against the internationalization process model. Mir Manag. Int. Rev. 1997, 37, 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Calantone, R.J.; Zhao, Y. Tacit knowledge transfer and firm innovation capability. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 18, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Roth, K. Adoption of an Organizational Practice by Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations: Institutional and Relational Effects. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, U.; Zander, L. Opening the grey box: Social communities, knowledge and culture in acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chu, H.H.; Chen, Y.Q. Accounting robustness, property right and value creation effect of cross-border M&As. Reform Econ. Syst. 2017, 4, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C. Top-management-team tenure and organizational outcomes: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaw, Y.L.; Lin, W.T. Corporate elite characteristics and firm’s internationalization: CEO-level and TMT-level roles. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Stale in the saddle: CEO tenure and the match between organization and environment. Manag. Sci. 1991, 37, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Al-Shammari, H.A.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.H. CEO duality leadership and corporate diversification behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkovich, G.T.; Newman, J.M.; Milkovich, C. Compensation; Irwin/McGraw-Hill: Burr Ridge, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cowherd, D.M.; Levine, D.I. Product quality and pay equity between lower-level employees and top management: An Investigation of Distributive Justice Theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1992, 37, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.A.; Hambrick, D.C. Pay disparities within top management groups: Evidence of harmful effects on performance of high-technology firms. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2005, 16, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, L. TMT’s acquisition experience and international acquisition performance: The moderating role of TMT’s pay dispersion. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2017, 31, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.W.; Lev, B.; Yeo, G.H. Executive pay dispersion, corporate governance, and firm performance. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2008, 30, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.F.; Yeh, Y.M.C.; Shih, Y.T. Tournament theory’s perspective of executive pay gaps. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, D. Competing for talent: China’s strategies to reverse the brain drain. Int. Labor Rev. 2006, 145, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.; Zhang, C.M. Institutional logics and power sources: Merge and acquisition decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, M.; Liao, G.; Yu, X. The brain gain of corporate boards: Evidence from China. J. Financ. 2015, 70, 1629–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.; Klasa, S.; Walcott, N. Do firms have leverage targets? Evidence from acquisitions. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kan, S. Enterprise culture and M&A performance. Manag. World 2014, 11, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Alimov, A. Labor market regulations and cross-border mergers and acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 984–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Brass, D. Cross-border acquisitions and the asymmetric effect of power distance value difference on long-term post-acquisition performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 972–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolyi, G.A.; Taboaa, A.G. Regulatory arbitrage and cross-border bank acquisitions. J. Financ. 2015, 70, 2395–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Meier, D. What is M&A performance? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Sevilir, M. Board connections and M&A transactions. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 103, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Audia, P.G.; Greve, H.R. Less likely to fail: Low performance, firm size, and factory expansion in the shipbuilding industry. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C. Corporate diversification. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Singhm, H. The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 19, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Introduction: Geert Hofstede’s culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Acad. Manag. Exec. (1993–2005) 2004, 18, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, S.B.; Schlingemann, F.P.; Stulz, R.M. Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. J. Financ. Econ. 2004, 73, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihanyi, L.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Daily, C.M.; Dalton, D.R. Composition of the top management team and firm international diversification. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1157–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuil, D.A.; Datta, D.K. Effects of industry- and region-specific acquisition experience on value creation in cross-border acquisitions: The moderating role of cultural similarity. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 766–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Z.; Yang, G.N.; Yu, X.F. A study on the impact of the board of directors’ foreign backgrounds on the degree of companies’ internalization. Int. Bus. 2017, 1, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dikova, D.; Sahib, P.R.; Witteloostuijn, A.V. Cross-border acquisition abandonment and completion: The effect of institutional differences and organizational learning in the international business service industry, 1981–2001. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, P.C.; Louca, C.; Petrou, A.P. Organizational learning and corporate diversification performance. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3270–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.CBA(△TQ) | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2.GFE | 0.11 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 3.SFE | 0.15 | 0.08 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4.Tenure | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5.PayGap | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 6.Firm Size | −0.14 | 0.17 | −0.40 | −0.20 | −0.38 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 7.Leverage | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.18 | −0.29 | 0.51 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 8.Firm growth | −0.38 | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 1 | |||||||||

| 9.Cash | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.14 | −0.00 | 1 | ||||||||

| 10.R&D | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.09 | −0.31 | −0.36 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 1 | |||||||

| 11.Home GDP | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.94 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 1 | ||||||

| 12.Home GDP growth | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.72 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.15 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.83 | 1 | |||||

| 13.Host GDP | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.45 | −0.0 | 0.07 | −0.43 | −0.06 | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.10 | −0.47 | −0.42 | 1 | ||||

| 14.Host GDP growth | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.48 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.43 | −0.06 | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.48 | −0.42 | 0.50 | 1 | |||

| 15.Openness | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.34 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.37 | −0.21 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 1 | ||

| 16.Institutional distance | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.00 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 1 | |

| 17.Cultural distance | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.45 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.43 | −0.06 | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.06 | −0.48 | −0.46 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.38 | −0.11 | 1 |

| 18.Economic distance | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.48 | 0.11 |

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | VIF | Variables | Mean | S.D. | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBA(△TQ) | 0.02 | 0.53 | - | R&D | 0.36 | 0.01 | 1.29 |

| GFE | 0.22 | 0.06 | 1.49 | Home GDP | 29.65 | 0.07 | 1.52 |

| SFE | 0.09 | 0.03 | 1.53 | Home GDP growth | 8.67 | 0.06 | 1.48 |

| Tenure | 2.60 | 0.12 | 1.09 | Host GDP | 27.79 | 0.68 | 2.39 |

| Pay Gap | 0.36 | 0.03 | 1.26 | Host GDP growth | 2.31 | 0.95 | 1.31 |

| Firm Size | 22.91 | 0.18 | 2.27 | Openness | 1.00 | 0.45 | 4.11 |

| Leverage | 0.46 | 0.04 | 1.95 | Institutional Distance | 3.37 | 0.58 | 3.70 |

| Firm Growth | 0.51 | 0.27 | 1.04 | Cultural Distance | 3.53 | 0.58 | 3.24 |

| Cash | 0.13 | 0.19 | 1.14 | Economic Distance | –1.69 | 0.33 | 4.32 |

| Variables. | Baseline | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFE | 0.351 | 0.321 | 2.745 ** | ||||

| SFE | 2.145 ** | 2.144 * | 7.357 ** | ||||

| Tenure | 0.031 * | 0.009 | |||||

| GFE X Tenure | 0.128 * | ||||||

| SFE X Tenure | 0.250 ** | ||||||

| Pay Gap | −1.741 * | −0.912 | |||||

| GFE X Pay Gap | −5.302 ** | ||||||

| SFE X Pay Gap | −2.75 * | ||||||

| Firm Size | −0.239 *** | −0.255 *** | −0.253 *** | −0.255 *** | −0.252 *** | −0.258 *** | −0.237 *** |

| Leverage | 0.755 | 0.794 | 0.765 | 0.800 | 0.776 | 1.000 * | 0.873 |

| Firm Growth | −0.969 *** | −0.970 *** | −0.976 *** | −0.965 *** | −0.968 *** | −0.978 *** | −0.989 *** |

| Cash | 0.280 | 0.288 | 0.298 | 0.285 | 0.295 | 0.323 | 0.333 * |

| R&D | 0.814 | 0.788 | 0.710 | 0.821 | 0.774 | 0.590 | 0.597 |

| Home GDP | 0.087 | 0.146 | 0.178 | 0.132 | 0.159 | 0.211 | 0.193 |

| Home GDP Growth | 0.408 | 0.255 | 0.251 | 0.298 | 0.305 | −0.026 | 0.124 |

| Host GDP | −0.000 | −0.002 | −0.038 | −0.000 | −0.036 | −0.008 | −0.0478 |

| Host GDP Growth | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 0.022 | 0.0260 |

| Openness | −0.050 | −0.044 | −0.090 | −0.039 | −0.084 | −0.070 | −0.121 |

| Institutional distance | −0.027 | −0.034 | −0.019 | −0.035 | −0.019 | −0.009 | −0.00605 |

| Cultural distance | 0.065 | 0.069 | 0.046 | 0.072 | 0.050 | 0.065 | 0.0424 |

| Economic distance | 0.113 | 0.106 | 0.119 | 0.106 | 0.123 | 0.149 | 0.151 |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-square | 0.8660 | 0.8663 | 0.8664 | 0.8660 | 0.8656 | 0.8655 | 0.8685 |

| Wald chi2 | 1199 | 1198.71 | 1211.00 | 1180.50 | 1182.55 | 1203.23 | 1214.04 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFE_Work | 0.450 * | 0.435 * | |

| SFE_Education | 0.314 | 0.287 | |

| Firm Size | −0.257 *** | −0.239 *** | −0.256 *** |

| Leverage | 0.725 | 0.752 | 0.723 |

| Firm growth | −0.977 *** | −0.972 *** | −0.979 *** |

| Cash | 0.294 | 0.313 | 0.324 |

| R&D | 0.569 | 0.697 | 0.469 |

| Home GDP | 0.169 | 0.144 | 0.218 |

| Home GDP growth | 0.299 | 0.219 | 0.129 |

| Host GDP | −0.030 | −0.012 | −0.039 |

| Host GDP growth | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.025 |

| Openness | −0.078 | −0.072 | −0.097 |

| Institutional distance | −0.016 | −0.016 | −0.006 |

| Cultural distance | 0.042 | 0.059 | 0.037 |

| Economic distance | 0.127 | 0.128 | 0.140 |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-square | 0.8666 | 0.8662 | 0.8667 |

| Wald chi2 | 1207.29 | 1204.92 | 1211.69 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, Z.; Lin, R.; Mi, J.; Li, N. Improving Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&A Sustainability in the Globalization Age—Research on Acquisition and Application of the Foreign Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113180

Xie Z, Lin R, Mi J, Li N. Improving Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&A Sustainability in the Globalization Age—Research on Acquisition and Application of the Foreign Experience. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113180

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Zaiyang, Runhui Lin, Jie Mi, and Na Li. 2019. "Improving Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&A Sustainability in the Globalization Age—Research on Acquisition and Application of the Foreign Experience" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113180

APA StyleXie, Z., Lin, R., Mi, J., & Li, N. (2019). Improving Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&A Sustainability in the Globalization Age—Research on Acquisition and Application of the Foreign Experience. Sustainability, 11(11), 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113180