Circular Economy Indicators as a Supporting Tool for European Regional Development Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

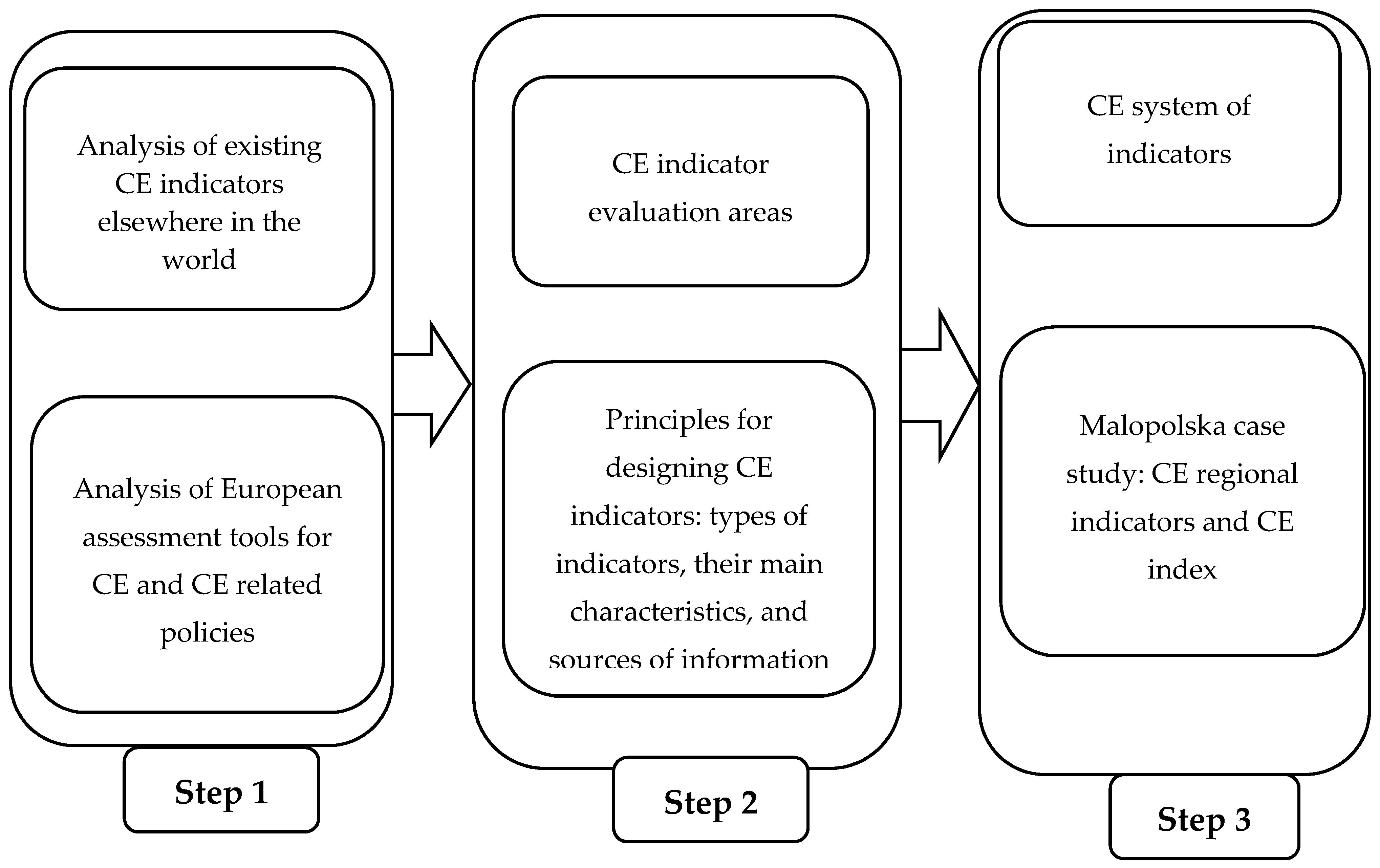

2. The Concept and Method of the Study

- Step 1.

- Firstly, analysis was conducted of existing CE indicators employed around the world, examining their compatibility for use under European conditions. Existing indicators for evaluation of EU policies related to CE issues were also examined. As CE is promoted as a new strategy of development, some measures of evaluating other public development policies could be applied in the case of CE as well.

- Step 2.

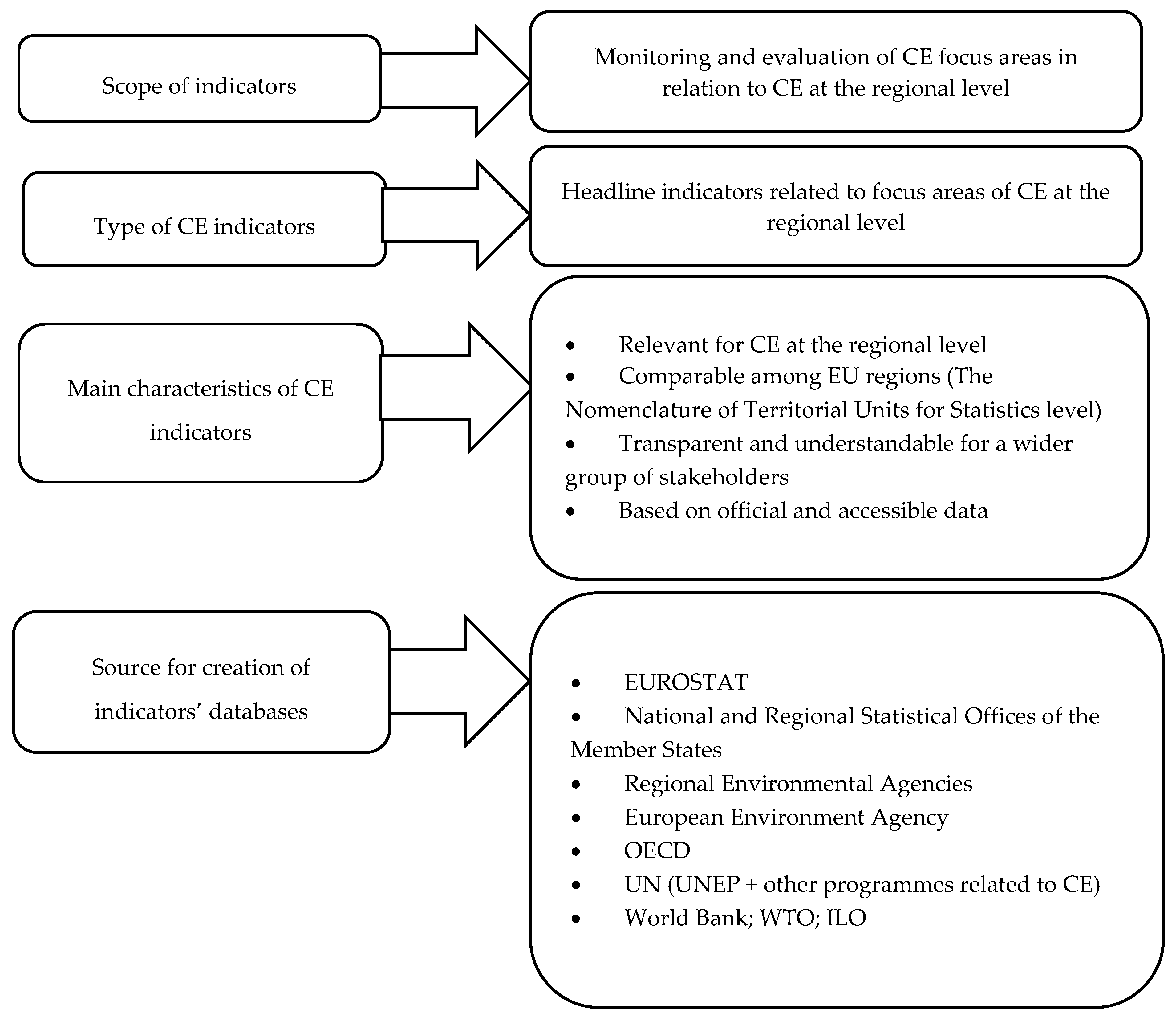

- This step identified the main characteristics necessary for region-specific CE indicators, identifying sources for data collection.

- Step 3.

- The final step analysed the research conducted in the first two steps in order to propose a system of indicators for areas identified as the most important for CE at the regional level. A case study was prepared (for the Malopolska region of Poland) to present a practical application of the indicator system.

3. Analysis of Existing Approaches and Indicators of CE-Based Regional Development

3.1. Analysis of Existing CE Indicators

3.2. European Assessment Tools for CE

4. CE System of Indicators: Assumptions for Design and Proposals for European Regional Indicators

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- (7)

- (8)

- (9)

- (10)

- (11)

- (12)

5. CE Malopolska Region: Case Study

5.1. Malopolska Region

- educational campaign “You Segregate-You Recover” with the purpose of dissemination of information on the Waste Management Plan of the region and the new municipal waste management system;

- regional competition “LPR Clean Community” in cooperation with the Voivodeship Fund of Environmental Protection and Water Management with the purpose of identifying and promoting LPR rural and rural–urban communities that have the most effective systems of waste management at the regional level;

- regional competition “Pass it on” for association of housewives in rural areas with the purpose of organizing information actions aimed at promoting a waste management hierarchy, waste reuse, exchange and decoration and repair of old and used goods; and

- upcycling of Malopolska promotional materials after rebranding—the “eco-campaign promoting waste management hierarchy: recycling/upcycling, promotion of repair networks and reuse”; actions taken were focused on upcycling of out-dated banners and sewing of ecological bags distributed among the LPR population and carrying out an information campaign on a radio station dedicated to the prevention of waste.

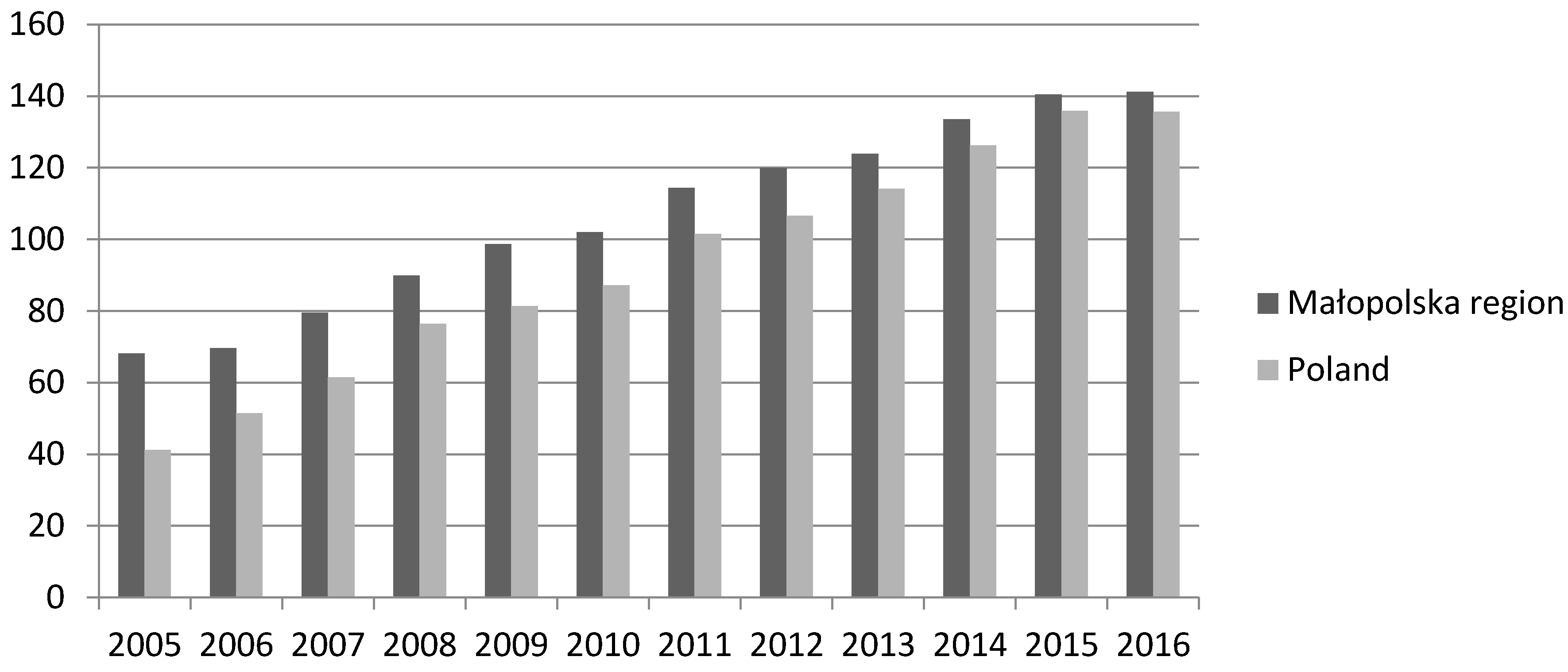

5.2. CE Progress in the Malopolska Region

5.2.1. CE Regional Indicators

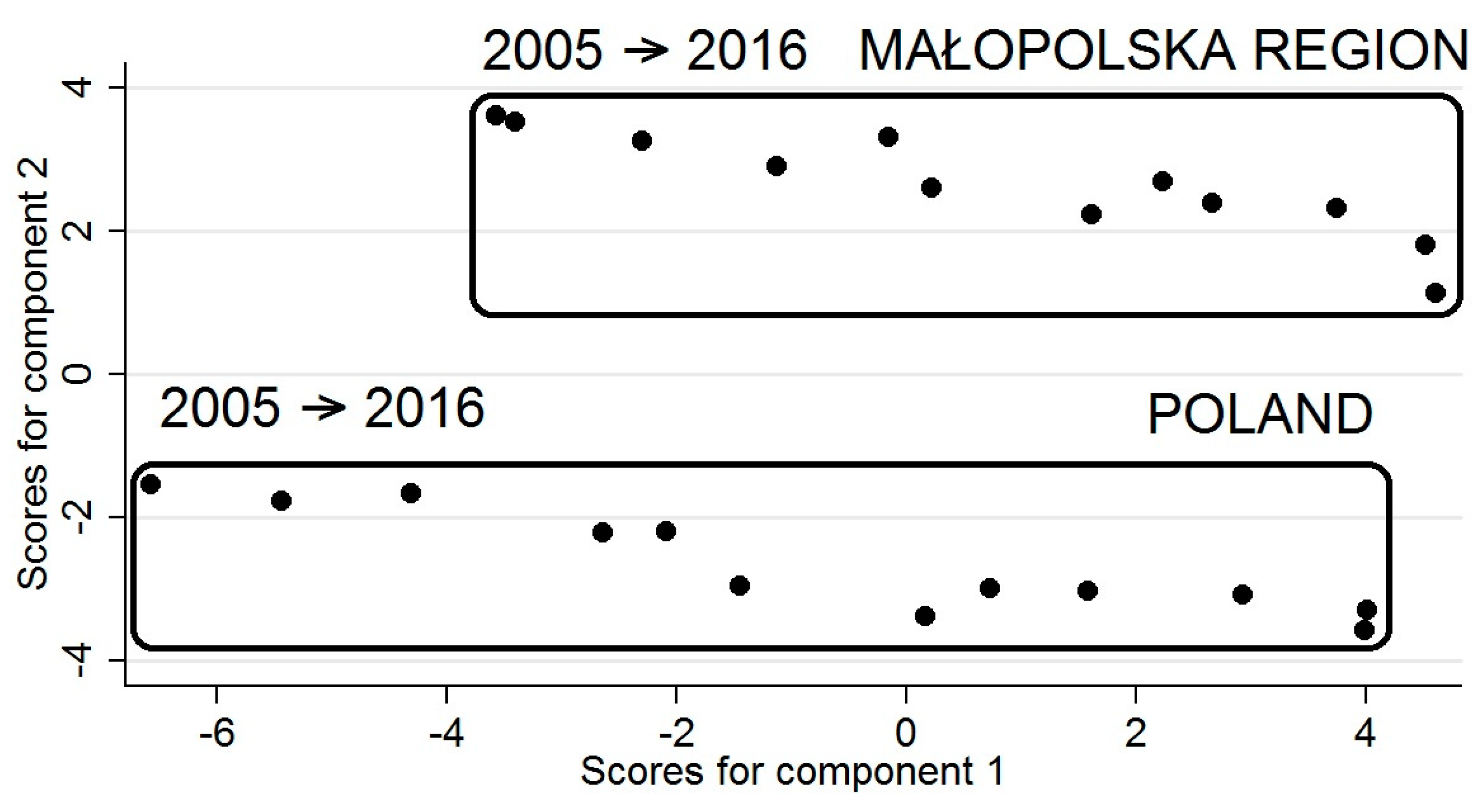

5.2.2. Construction of the CE Index

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

.

.Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kobza, N.; Schuster, A. Building a responsible Europe—The value of circular economy. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy e a new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech, T.; Bleischwitz, R.; Doranova, A.; Panayotopoulos, D.; Roman, L. Mapping Industrial Symbiosis Development in Europe_ typologies of networks, characteristics, performance and contribution to the Circular Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, E.S.; Cioca, L.-I.; Dan, V.; Ciomos, A.O.; Crisan, O.A.; Barsan, G. Studies and investigation about the attitude towards sustainable production, consumption and waste generation in line with circular economy in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, E.C.; Ragazzi, M.; Torretta, V.; Castagna, G.; Adami, L.; Cioca, L.I. Circular economy and waste to energy. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1968, 030050. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, T.G.; Varbanov, P.S.; Su, R.; Ong, B.; Lal, N. Frontiers in process development, integration and intensification for circular life cycles and reduced emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzi, M.; Fedrizzi, S.; Rada, E.C.; Ionescu, G.; Ciudin, R.; Cioca, L.I. Experiencing Urban Mining in an Italian Municipality towards a Circular Economy vision. Energy Procedia 2017, 119, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D.; Droste, N.; Allen, B.; Kettunen, M.; Lahtinen, K.; Korhonen, J.; Leskinen, P.; Matthies, B.; Toppinen, B. Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 716–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G.; Tornese, F. Measuring circular economy strategies through index methods: A critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.C.; Che, F.; Fan, S.S.; Gu, C. Ownership governance, institutional pressures and circular economy accounting information disclosure an institutional theory and corporate governance theory perspective. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2013, 8, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazami, N.; Ymeri, P.; Fogarassy, C. Investigating the current business model innovation trends in the biotechnology industry. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z. Institutional pressures, sustainable supply chain management, and circular economy capability: Empirical evidence from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhao, H.; Guo, S. Evaluating the comprehensive benefit of eco-industrial parks by employing multi-criteria decision making approach for circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2262–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Doberstein, B. Developing the circular economy in China: Challenges and opportunities for achieving “leapfrog development”. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Fu, J.; Sarkis, J.; Xue, B. Towards a national circular economy indicator system in China: An evaluation and critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 23, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Circular Economy in the Netherlands by 2050. Dutch Ministry of Environment 2016. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/ministerial/whatsnew/2016-ENV-Ministerial-Netherlands-Circular-economy-in-the-Netherlands-by-2050.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Leading the Cycle Finnish Road Map to a Circular Economy 2016–2025. Sitra Studies 121. 2016. Available online: https://media.sitra.fi/2017/02/24032659/Selvityksia121.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Germany-German Resource Efficiency Programme (ProgRess II). Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety 2016. Available online: http://www.bmub.bund.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/german_resource_efficiency_programme_ii_bf.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Leading the Transition: A Circular Economy Action Plan for Portugal: 2017–2020. Ministry of Environment of Portugal 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/strategy_-_portuguese_action_plan_paec_en_version_3.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Towards a Model of Circular Economy for Italy—Overview and Strategic Framework. Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea Ministry of Economic Development 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/strategy_-_towards_a_model_eng_completo.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- France Unveils Circular Economy Roadmap. The French Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/FREC%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Roadmap towards the Circular Economy in Slovenia. Circular Change 2018. Available online: http://www.vlada.si/fileadmin/dokumenti/si/projekti/2016/zeleno/ROADMAP_TOWARDS_THE_CIRCULAR_ECONOMY_IN_SLOVENIA.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Promoting Green and Circular Economy in Catalonia: Strategy of the Government of Catalonia. The Government of Catalonia. 2015. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/strategies; http://mediambient.gencat.cat/web/.content/home/ambits_dactuacio/empresa_i_produccio_sostenible/economia_verda/impuls/IMPULS-EV_150519.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Programme Régional En Economie Circulaire 2016–2020. Ministry of Housing, Quality of Life, Environment and Energy of Belgium; Minister of the Economy, Employment and Professional Training 2016. Available online: http://document.environnement.brussels/opac_css/elecfile/PROG_160308_PREC_DEF_FR (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland Report. The Scottish Government. 2016. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/making_things_last.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Circular Amsterdam: A vision and Action Agenda for the City and Metropolitan Area. City Government of Amsterdam. 2016. Available online: https://www.circle-economy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Circular-Amsterdam-EN-small-210316.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- White Paper on the Circular Economy of the Greater Paris. City Government of Paris. 2016. Available online: https://api-site.paris.fr/images/77050 (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Extremadura 2030: Strategy for a Green and Circular Economy. Regional Government of Extremadura. 2017. Available online: http://extremadura2030.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/estrategia2030.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- London’s Circular Economy Route Map. London Waste and Recycling Board. 2017. Available online: https://www.lwarb.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/LWARB-London%E2%80%99s-CE-route-map_16.6.17a_singlepages_sml.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Circular Flanders Kick-off Statement. Vlaanderen Circulair. 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/kick-off_statement_circular_flanders.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Welfens, P.; Bleischwitz, R.; Geng, Y. Resource efficiency, circular economy and sustainability dynamics in China and OECD countries. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2017, 14, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B.; Kovacs, A.; Szőke, L.; Takacs-Gyorgy, K.A. Circular Evaluation Tool for Sustainable Event Management—An Olympic Case Study. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2017, 14, 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- De Medici, S.; Riganti, P.; Viola, S. Circular Economy and the Role of Universities in Urban Regeneration: The Case of Ortigia, Syracuse. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of European Communities. Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Programme for Europe; Communication No. 398; (COM (2014), 398); Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/pdf/circular-economy-communication.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Commission of European Communities. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; Communication No. 614; (COM (2015), 614); Commission of European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8a8ef5e8-99a0-11e5-b3b7-01aa75ed71a1.0012.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Commission of European Communities. Communication No. 33, 2017. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan (COM (2017), 33). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Petit-Boix, A.; Leipold, S. Circular economy in cities: Reviewing how environmental research aligns with local practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Abreu, M.C.S.; Ceglia, D. On the implementation of a circular economy: The role of institutional capacity-building through industrial symbiosis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 138, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Doberstein, B.; Fujita, T. Implementing China’s circular economy concept at the regional level: A review of progress in Dalian, China. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Mingyue, C.; Qiongqiong, G. Research on the Circular Economy in West China. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, Q.; Chen, M. Study and Integrative Evaluation on the development of Circular Economy of Shaanxi Prince. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.-G. Empirical Analysis of Regional Circular Economy Development--Study Based on Jiangsu, Heilongjiang, Qinghai Province. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Geng, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Sterr, T. Comparative assessment of circular economy development in China’s four megacities: The case of Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai and Urumqi. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. When stakeholder pressure drives the circular economy Measuring the mediating role of innovation capabilities. Manag. Decis. 2018, 57, 904–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bi, J.; Fan, Z.; Yuana, Z.; Gea, J. Eco-efficiency analysis of industrial system in China: A data envelopment analysis approach. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomenko, A.; Nelen, D.; Gillabel, J.; Rechberger, H. Measuring the circular economy—A Multiple Correspondence Analysis of 63 metrics. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 210, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, S.G.; Godina, R.; Matias, J.C.O. Proposal of a sustainable circular index for manufacturing companies. Resources 2017, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, W.; Geng, Y.; Huang, B.; Bartekova, E.; Bleischwitz, R.; Turkeli, S.; Kemp, R.; Domenech, T. Circular Economy Policies in China and Europe. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-Q.; Shi, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhu, W.-D. Effectiveness of the policy of circular economy in China: A DEA-based analysis for the period of 11th five-year-plan. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinberg, A.; Nesic, J.; Savain, R.; Luppi, P.; Sinnott, P.; Petean, F.; Pop, F. From collision to collaboration—Integrating informal recyclers and re-use operators in Europe: A review. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 34, 820–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botezat, E.A.; Dodescu, A.O.; Văduva, S.; Fotea, S.L. An Exploration of Circular Economy Practices and Performance among Romanian Producers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, D.A.; Negro, S.O.; Verweij, P.A.; Kuppens, D.V.; Hekkert, M.P. Exploring barriers to implementing different circular business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Heshmati, A.; Geng, Y.; Yu, X. A review of the circular economy in China: Moving from rhetoric to implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 42, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIa, C.-R.; Zhang, J. Evaluation of Regional Circular Economy Based on Matter Element Analysis. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 11, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Europe 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Communication from the Commission. Communication No. 2020, 2010 (COM (2010), 2020). Brussels 2010. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- A Sustainable Europe for a Better World: A European Union Strategy for Sustainable Development Communication from the Commission; (COM(2001)264); Brussels. 2001. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/innovation/pdf/library/strategy_sustdev_en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Next Steps for a Sustainable European Future European Action for Sustainability. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of The Regions; (COM(2016) 739); Brussels. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/communication-next-steps-sustainable-europe-20161122_en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Towards Improved Methodologies for Eurozone Statistics and Indicators. Communication of the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on Eurozone Statistics; (COM(2002) 661). 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2002:0661:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- European Pillars of Social Right. European Commission. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/social-summit-european-pillar-social-rights-booklet_en.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Eurostat: CE overview. 2018. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/circular-economy (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Circular Economy in Europe. Developing the Knowledge Base. European Environmental Agency Report No 2/2016; Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union 2016. Available online: https://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/sites/default/files/Circular%20economy%20in%20Europe.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Indicators for the EU Sustainable Development Goals. Eurostat. 2015. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/sdi/indicators (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Sustainable development in the European Union 2015. Monitoring report of the EU Sustainable Development Strategy. Eurostat. 2015. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/6975281/KS-GT-15-001-EN-N.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Towards the Circular Economy 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. 2012. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Delivering the Circular Economy: A Toolkit for Policymakers. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/EllenMacArthurFoundation_PolicymakerToolkit.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 618–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleva, V.; Bodkin, G.; Todorova, S. The need for better measurement and employee engagement to advance a circular economy: Lessons from Biogen’s “zero waste” journey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskaite, J.; Jouhara, H.; Czajczynska, D.; Stanchev, P.; Katsou, E.; Rostkowski, P.; Thorne, R.J.; Colon, J.; Ponsa, S.; Al-Mansour, F.; et al. Municipal solid waste management and waste-to-energy in the context of a circular economy and energy recycling in Europe. Energy 2017, 141, 2013–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Mendonça, S. Eco-innovation in the transition to a circular economy: An analytical literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2999–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.; Cabras, I. The transition of Germany’s energy production, green economy, low carbon economy, socio-environmental conflicts, and equitable society. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Dong, L.; Rend, J.; Zhang, Q.; Han, L.; Fu, H. Carbon footprints of urban transition: Tracking circular economy promotions in Guiyang, China. Ecol. Model. 2017, 365, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.I.; Krogstiea, J. On the social shaping dimensions of smart sustainable cities: A study in science, technology, and society. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 29, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Tan, R.R.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Chien, C.-F.; Kuo, T.C. Circular economy meets industry 4.0: Can big data drive industrial symbiosis? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 131, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breure, A.M.; Lijzen, J.P.A.; Maring, L. Soil and land management in a circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saavedra, Y.M.B.; Iritani, D.R.; Pavan, A.L.R.; Ometto, A.R. Theoretical contribution of industrial ecology to circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladu, L.; Blind, K. Overview of policies, standards and certifications supporting the European bio-based economy. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 8, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W. The product life factor. In An Inquiry into the Nature of Sustainable Societies. The Role of the Private Sector; Orr, G.S., Ed.; Houston Area Research Centre: Houston, TX, USA, 1982; pp. 72–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godelnik, R. Millennials and the sharing economy: Lessons from a ‘buy nothing new, share everything month’ project. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Davidson, A.; Laroche, M. What managers should know about the sharing economy. Bus. Horizons 2017, 60, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Towfique, R.; Rahman, M.H.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K. Drivers to sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy: A perspective of leather industries in Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 174, 1366–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homrich, A.S.; Galvao, G.; Abadia, L.G.; Carvalho, M.M. The circular economy umbrella: Trends and gaps on integrating pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malopolska Region Report. Marshal Office of Malopolska Voivodeship. Voivodeship Labour Office in Cracow, Regional Center for Social Policy in Cracow: 2016. (In Polish). Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/publikacje/rozwoj-regionalny/wojewodztwo-malopolskie-2016 (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Report on the State of the Environment in Malopolska in the Years 2013–2015; Voivodeship Inspectorate for Environmental Protection in Cracow, Cracow. 2016; (In Polish). Available online: http://www.krakow.pios.gov.pl/Press/publikacje/raporty/raport16/raport2016.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Air Quality in Cities Database. World Health Organization. 2016. Available online: www.who.int/phe/health_topics/outdoorair/databases/cities/en (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Avdiushchenko, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Circular Economy Implementation in the Lesser Poland Region (LPR). In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Waste Management and Technology 2016, Tsinghua University, Basel Convention Regional Centre for Asia and the Pacific, Beijing, China, 21–24 March 2018; pp. 328–340. [Google Scholar]

- SYMBI Interreg Europe. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/symbi/ (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Waste Management Plan for the Malopolska (Lesser Poland) Region. Resolution No. XXXIV/509/17 of the Lesser Poland (Malopolskie) Voivodship Assembly from March 27, 2017 on amending the Resolution No. XI / 125/03 of the lesser Poland (Malopolska) Region Assembly from 25 339 August 2003 on the Waste Management Plan of the Lesser Poland (Malopolskie) Voivodship. Cracow. 2016. (In Polish). Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/_userfiles/uploads/PGOWM_2016-2022.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Spatial Management Plan for the Lesser Poland (Malopolska) Region. Resolution of the Regional Assembly of the Małopolska Region from 22 December 2003. Krakow. 2003; (with Updates in 2018); (In Polish). Available online: http://edziennik.malopolska.uw.gov.pl/WDU_K/2018/3215/akt.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- NUTS 2016 Classification. Eurostat. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/background (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Li, W.F.; Zhang, T.Z. Research on the circular economy evaluation index system in resource based city. Econ. Manag. J. 2005, 8, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.H. Study on indicator system of urban circular economy development. Econ. Manag. 2006, 16, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Wang, H.H.; Zhao, R.M. Assessment of development level of circular economy and its countermeasures in Qingdao. J. Qingdao Univ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 24, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, X.J. Research on circular economy development indicator system and demonstrable assessment. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2005, 15, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rantaa, V.; Aarikka-Stenroosa, L.; Ritalab, P.; Mäkinena, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Monitored EU Policy/Area/Strategy | Characteristics/Types of Indicators | Areas of Monitoring | Relevance for CE Monitoring at the Regional Level ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUROPE 2020 the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs for the current decade. It emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth as a way to overcome the structural weaknesses in Europe’s economy, improve its competitiveness and productivity and underpin a sustainable social market economy. | Six headline indicators | Employment, R&D, climate change and energy, education, poverty and social inclusion. | Partly relevant |

| SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Indicators for monitoring the sustainable development goals (SDGS) in an EU context (the set of indicators was established in 2017, changing the previous one which was used from 2005 to 2015 and was in line with the EU Sustainable Development Strategy). | The set is structured along the 17 SDGs and includes 100 different indicators. | Poverty, agriculture and nutrition, health, education, gender equality, water, energy, economy and labour, infrastructure and innovations, inequality, cities, consumption and production, climate, oceans, ecosystems, institutions and global partnership. | Highly relevant |

| EUROPEAN PILLAR OF SOCIAL RIGHTS | Headline indicators (5 indicators in the first group, 5 indicators in the second group and 4 indicators in the third group). Secondary indicators (10 indicators in the first group, 6 indicators in the second group and 5 indicators in the third group). | Group 1. Equal opportunities and access to the labour market (education, skills and lifelong learning, gender equality in the labour market, inequality and upward mobility, living conditions and poverty and youth). Group 2. Dynamic labour markets and fair working conditions (labour force structure, labour market dynamics and income including employment-related). Group 3. Public support/social protection and inclusion (impact of public policies on reducing poverty, childcare, healthcare and digital access). | Partly relevant |

| CE Specific Area | Evaluation Aspects for Monitoring | Possible Indicators for Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Economic prosperity economy taking into account financial aspects of environmental actions | Economic growth, green economic growth, GDP per capita, green jobs, unemployment level, environmental taxes and levies (share of budget revenues) and business based on CE business models (share) | Increase in household income, income of households, euros per inhabitant or PPS based on final consumption per inhabitant, real growth rate of regional gross value added at basic pricepercentage change over previous year, poverty risk indicator (below the relative poverty line) after taking into account social transfers in income |

| Financial aspects of environmental actions | Green public procurement, expenditure on environmental education | |

| Zero-waste economy | Water, wastes, recycling, reuse, refurbishment and remanufacturing | Municipal waste generated per inhabitant in a region, generation of waste excluding major mineral wastes per GDP unit, generation of waste excluding major mineral wastes per GDP in relation to domestic material consumption, recycling rate of municipal waste, recycling rate of biowaste in kg per capita, recycling rate of all waste excepting major mineral waste in %, rate of reuse, rate of remanufacturing and refurbishment, wastewater reuse, wastewater treatment |

| Innovative economy | Innovation, eco-innovations | Eco-innovations, patents related to recycling sectors, secondary raw materials, renewal, regeneration, expenditure on research and development in relation to GDP, share of innovative enterprises by sector in general enterprises |

| Energy-efficient and renewable energy-based economy | Energy efficiency, renewable energy sources | Final energy intensity of GDP, energy efficiency in households (energy consumption per household), energy productivity (the indicator results from the division of the gross domestic product (GDP) by the gross inland consumption of energy for a given calendar year), electricity consumption for 1 million PLN (Polish currency) of GDP, expenditure on fixed assets for environmental protection related to saving electricity per capita |

| Low carbon economy | Air pollution, CO2 emissions | Carbon dioxide emissions, emission of particulates, outlays/expenditures on fixed assets serving environmental protection and water management related to protection of air and climate |

| Bioeconomy | Biofuels, biomass, bio-based products | Biofuels, biomass, bioproducts, number of patents in the field of biotechnology, expenditures on research and development (R&D) in the field of biotechnology |

| Service/performance economy | Product as service sector | Market share of “product as services sector” |

| Collaborating/sharing economy | Sharing services | Individual used any website or app to arrange an accommodation from another individual, individuals used dedicated websites or apps to arrange an accommodation from another individual, individuals used any website or app to arrange a transport service from another individual *, individuals used dedicated websites or apps to arrange a transport service from another individual |

| Smart economy | R&D in green sector | % of households with Internet access, % of individuals using cloud services, e-commerce indicator: Internet purchases by individuals in % during last 3 months, e-government activities indicator: Internet use in interaction with public authorities (last 12 months) in % of individuals, percentage of households with broadband access, enterprises that provided training to develop/upgrade ICT skills of their personnel (% of enterprises), enterprises with access to broadband Internet |

| Resource Efficient Economy | Resource efficiency, material efficiency | Productivity of resources (GDP per unit of resources used by the regional economy), regional consumption of materials, the circular material use rate (CMU) (% of recyclable materials used in the economy in relation to the total consumption of raw materials) |

| Social Economy | Social innovations, collaboration services (platforms), social awareness of environmental issues | Innovative social enterprises, collaboration services platforms set up by local citizens |

| Spatially effective economy | Public space, green areas, circular spaces, industrial symbiosis areas, urbanization level | Dispersion ratio of housing (number of buildings per 1 km2 area of the region), The area of public spaces in ha, urbanization rate, forest cover indicator, length of bicycle paths, share of legally protected areas in the total area, share of Natura 2000 areas in the total area, passenger transport: % using public mass transport services, % of travellers traveling by nonmotorized means of transport (on foot and bicycle), % of passenger cars |

| Dimensions | No. | Indicators | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic prosperity economy | 1.1 | GDP | per capita, fixed prices, PLN |

| 1.2 | Average life expectancy at birth for men | years | |

| 1.3 | Registered unemployment rate | % | |

| 1.4 | At-risk-of-poverty rate | % | |

| Zero-waste economy | 2.1 | Municipal waste collected selectively in relation to the total amount of municipal waste collected | % |

| 2.2 | Municipal waste collected per one inhabitant | tons/person | |

| 2.3 | Industrial and municipal wastewater purified in wastewater requiring treatment | % | |

| 2.4 | Outlays on fixed assets serving environmental protection and water management related to recycling and utilization of waste | per capita, fixed prices, PLN | |

| Innovative economy | 3.1 | Expenditures on research and development activities | per capita, fixed prices, PLN |

| 3.2 | Average share of innovative enterprises in the total number of enterprises | % | |

| 3.2 | Adults participating in education and training | % | |

| 3.4 | Patent applications for 1 million inhabitants | ||

| Energy-efficient and renewable energy-based economy | 4.1 | Share of renewable energy sources in total production of electricity | % |

| 4.2 | Outlays on fixed assets serving environmental protection and water management related to electricity saving | per capita, fixed prices, PLN | |

| 4.3 | Electricity consumption | kWh/person | |

| Low carbon economy | 5.1 | Carbon dioxide emission from plants especially noxious to air purity | tons/person |

| 5.2 | Emission of particulates | tons/1 km2 | |

| 5.3 | Passenger cars | Cars/1000 population | |

| 5.4 | Pollutants retained or neutralized in pollutant reduction systems in total pollutants generated from plants especially noxious to air purity | % | |

| 5.5 | Outlays on fixed assets serving environmental protection and water management related to protection of air and climate | per capita, fixed prices, PLN | |

| Smart economy | 6.1 | Households with personal computer with broadband connection to Internet | % |

| 6.2 | enterprises with access to the Internet via a broadband connection | % | |

| Spatially effective economy | 7.1 | Forest cover indicator | % |

| 7.2 | Street greenery and share of parks, lawns and green areas of the housing estate areas in the total area | % | |

| 7.3 | Urbanization rate | % |

| Component | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. 1 | 10.8542 | 0.4342 | 0.4342 |

| Comp. 2 | 7.77977 | 0.3112 | 0.7454 |

| Comp. 3 | 1.42008 | 0.0568 | 0.8022 |

| Comp. 4 | 1.24390 | 0.0498 | 0.8519 |

| Comp. 5 | 1.09559 | 0.0438 | 0.8957 |

| Comp. 6 | 0.89274 | 0.0357 | 0.9315 |

| Comp. 7 | 0.62868 | 0.0251 | 0.9566 |

| … | … | … | … |

| Comp. 23 | 0.00020 | 0.0000 | 1.000 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avdiushchenko, A.; Zając, P. Circular Economy Indicators as a Supporting Tool for European Regional Development Policies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113025

Avdiushchenko A, Zając P. Circular Economy Indicators as a Supporting Tool for European Regional Development Policies. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113025

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvdiushchenko, Anna, and Paweł Zając. 2019. "Circular Economy Indicators as a Supporting Tool for European Regional Development Policies" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113025

APA StyleAvdiushchenko, A., & Zając, P. (2019). Circular Economy Indicators as a Supporting Tool for European Regional Development Policies. Sustainability, 11(11), 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113025