Social Impact Bonds for a Sustainable Welfare State: The Role of Enabling Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Collaborations and Contractual Schemes

2.2. Alignment of Interests and Principal Agent Issues

2.3. Evaluation and Public Savings

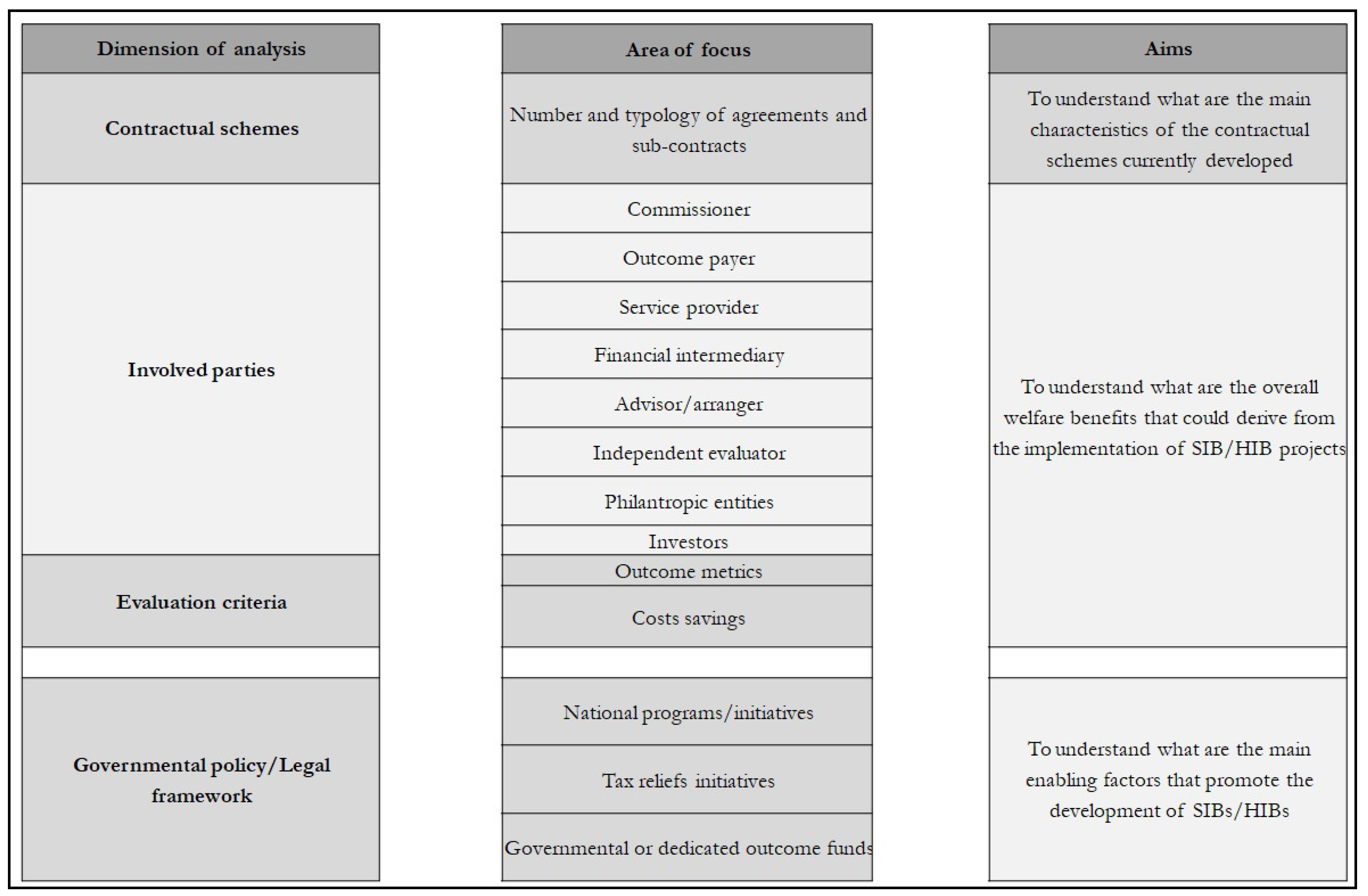

3. Research Design

3.1. Methodological Approach

3.2. Data Sources, Research Protocol and Coding Procedures

4. Case Studies

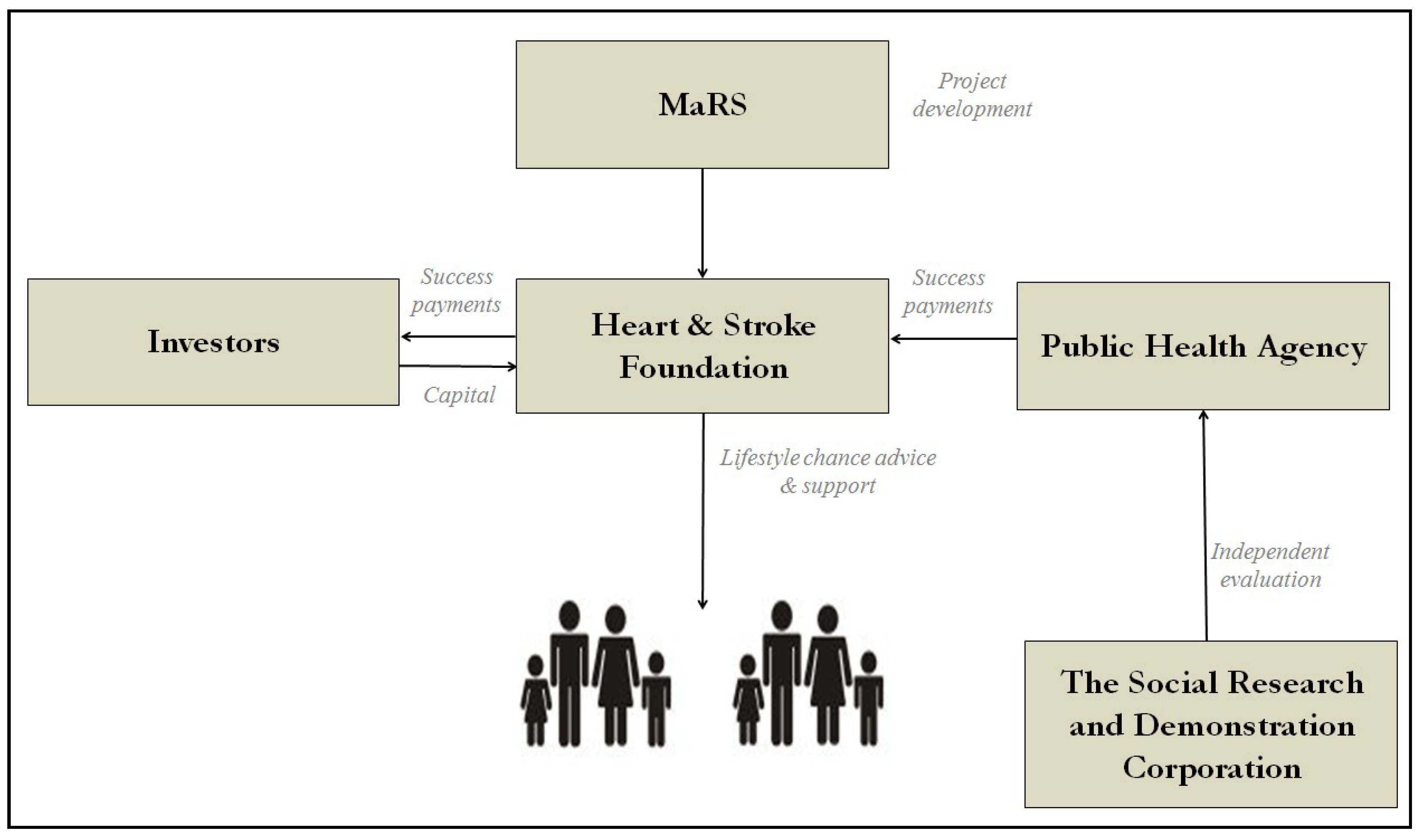

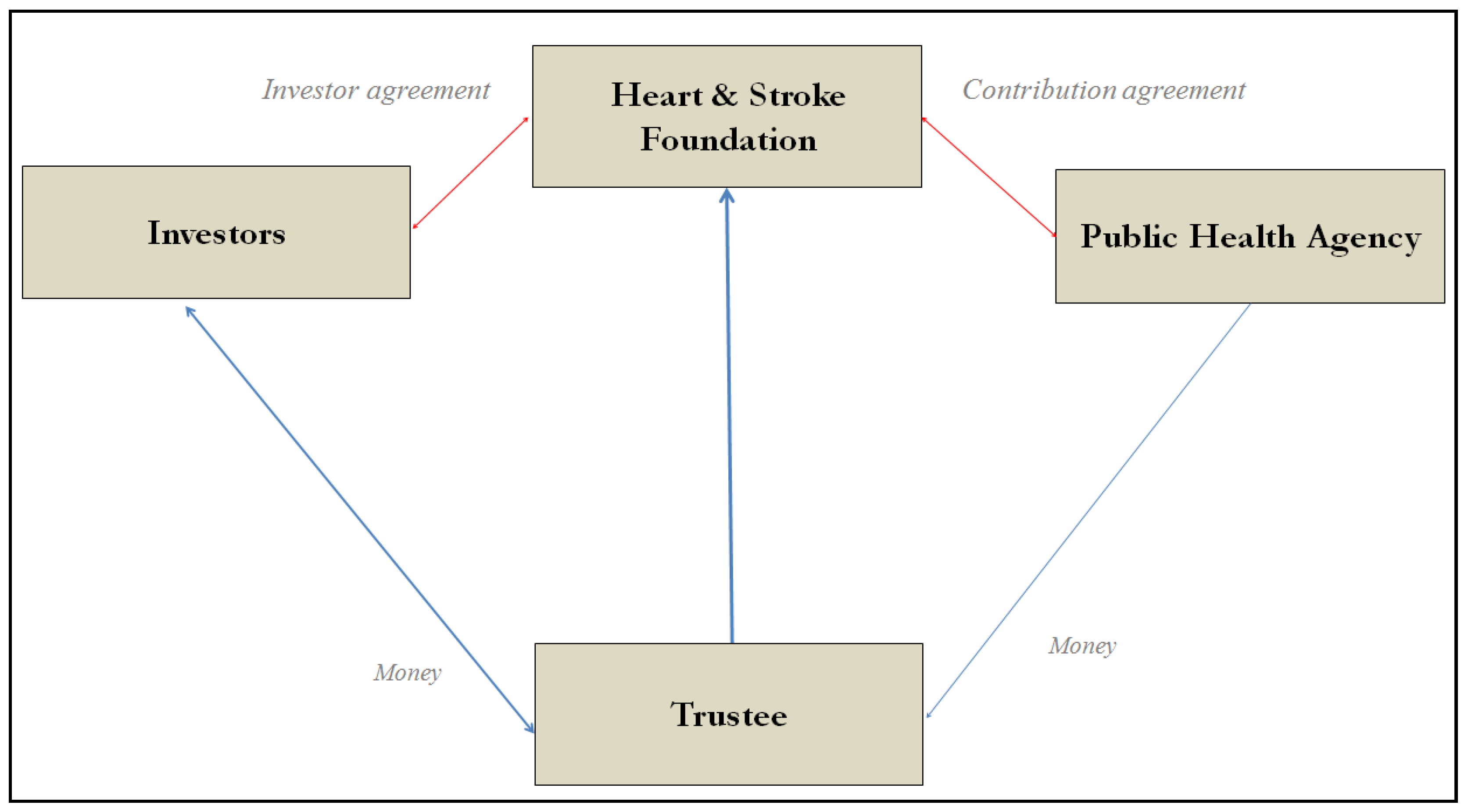

4.1. The Heart and Stroke Healthcare Impact Bond

4.2. The Ways to Wellness HIB

- Social Finance, who provided the estimation of the costs and benefits of the program, and supported the development of the financial model and the outcome metrics;

- Rocket Science, who provided support in managing the procurement of the service providers;

- NHS North East Quality Observatory System (NEQOS), who analyzed local data on long term conditions and provided support in identifying promising areas for cost savings; and

- Vital Services North East, who developed the management information systems and the IT infra-structure [63].

- -

- Outcome A: based on a change in wellbeing measured on the basis of a ‘Wellbeing Star’ at 6-month intervals. These outcomes are the main performance measures in the first two years of the project, with most of the funds coming from central government sources in the early years; and

- -

4.3. Mental Health and Employment Social Impact Bond

4.4. The Reconnections Social Impact Bond

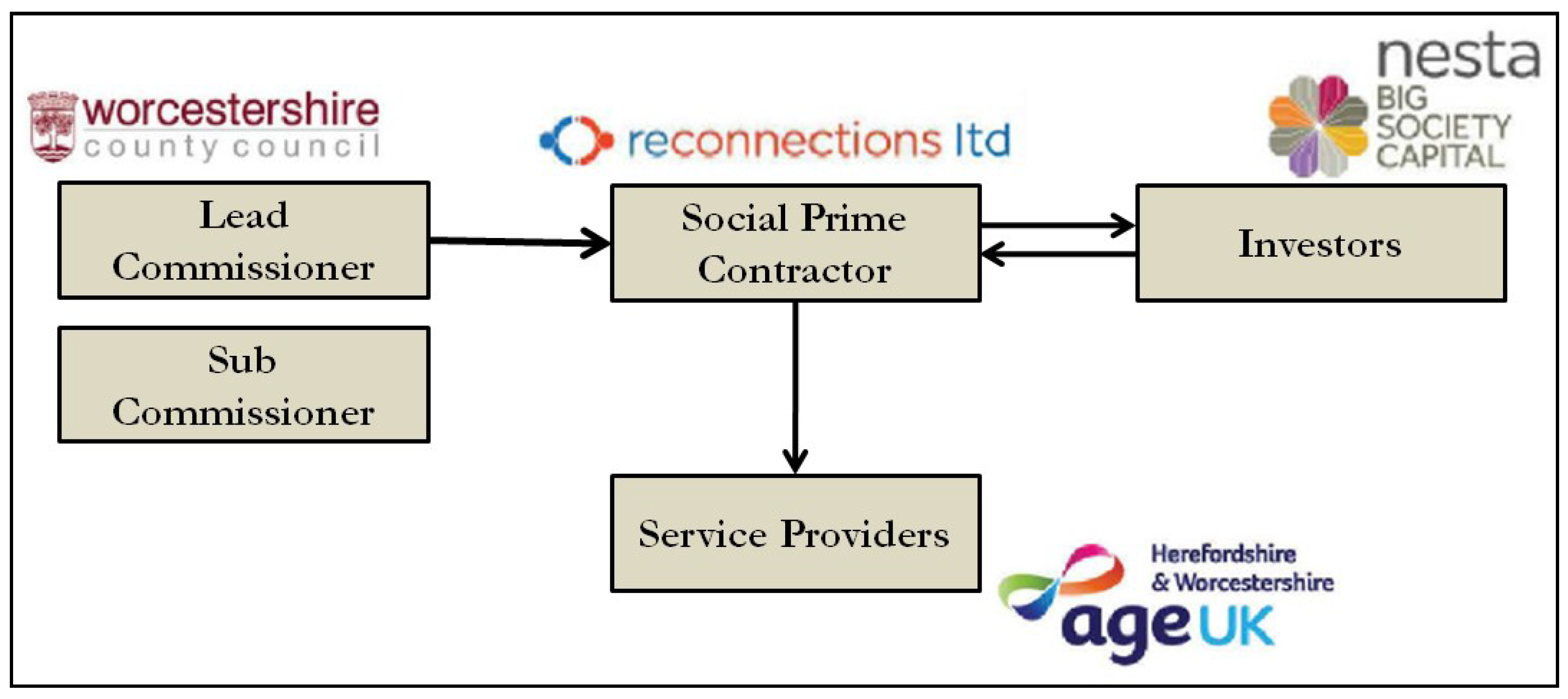

5. Insights from Case Studies: Main Research Findings

6. Enabling Factors

6.1. Building the Market Space: The Role of Governmental Policies

6.2. Improving Scalability and Replicability through Robust Contractual Schemes

6.3. Institutional Variables and the Role of Partnerships for Sustainability

6.4. Dampening the Role of Evaluation and Public Savings

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Towards Social Investment for Growth and Cohesion—Including Implementing the European Social Fund 2014–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karanikolos, M.; Mladovsky, P.; Cylus, J.; Thomson, S.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D.; MacKenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; McHugh, N.; Huckfield, L.; Roy, M.; Donaldson, C. Social Impact Bonds: Shifting the Boundaries of Citizenship. Soc. Policy Rev. 2014, 26, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, S.; Figueras, J.; Evetovits, T.; Jowett, M.; Mladovsky, P.; Maresso, A.; Cylus, J.; Karanikolos, M.; Kluge, H. Economic Crisis, Health Systems and Health in Europe: Impact and Implications for Policy; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, C.; Wirth, M. Market, metrics, morals: The Social Impact Bond as an emerging social policy instrument. Geoforum 2018, 90, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.S.; Brisbois, B.; Zerger, S.; Hwang, S.W. Social Impact Bonds as a Funding Method for Health and Social Programs: Potential Areas of Concern. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmiston, D.; Nicholls, A. Social Impact Bonds: The Role of Private Capital in Outcome-Based Commissioning. J. Soc. Policy 2017, 47, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E. Private finance for public goods: Social impact bonds. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2013, 16, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, A.; Migliavacca, M. Social Impact Bonds and Institutional Investors: An Empirical Analysis of a Complicated Relationship. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 48, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.; Tan, S.; Lagarde, M.; Mays, N. Narratives of Promise, Narratives of Caution: A Review of the Literature on Social Impact Bonds. Soc. Policy Adm. 2016, 52, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.; Albertson, K. Is payment by results the most efficient way to address the challenges faced by the criminal justice sector? Probat. J. 2012, 59, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, E. In the wake of austerity: Social impact bonds and the financialisation of the welfare state in Britain. New Political Econ. 2017, 22, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, J.; Jung, T. Social Impact Bonds: Exploring and Understanding an Emerging Funding Approach. In Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance; Lehner, O., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Social Finance. SIB Database. Available online: https://sibdatabase.socialfinance.org.uk/ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Rowe, R.; Stephenson, N. Speculating on health: Public health meets finance in ‘health impact bonds’. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carè, R.; Ferraro, G. Funding Innovative Healthcare Programs Through Social Impact Bonds: Issues and Challenges. China-USA Bus. Rev. 2019, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Quaglio, G.; Karapiperis, T.; Van Woensel, L.; Arnold, E.; McDaid, D. Austerity and health in Europe. Health Policy 2013, 113, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, M.; Trotta, A.; Chiappini, H.; Rizzello, A. Business Models for Sustainable Finance: The Case Study of Social Impact Bonds. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, I.; Jagelewski, A. Social Impact Bond: Technical Guide for Service Providers. Available online: https://learn.marsdd.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/MAR-SIB6939__Social-Impact-Bond-Technical-Guide-for-Service-Providers_FINAL-ELECTRONIC1.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Morley, J. The ethical status of social impact bonds. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, C.; Carter, E.; Dixon, R.; Airoldi, M. Walking the contractual tightrope: A transaction cost economics perspective on social impact bonds. Public Money Manag. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Finance UK. Social Impact Bond. The Early Years. Available online: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/sibs-early-years_social_finance_2016_final.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Giacomantonio, C. Grant-Maximizing but not Money-Making: A Simple Decision-Tree Analysis for Social Impact Bonds. J. Soc. Entrep. 2017, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, F.; Barbetta, G.P.; Godina, F. Paradoxes of social impact bonds. Soc. Policy Adm. 2018, 52, 1332–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, F.; Meyer, M. Social Impact Bonds and the Perils of Aligned Interests. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stid, D. Pay for success is not a panacea. Community Dev. Invest. Rev. 2013, 9, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Azemati, H.; Belinsky, M.; Gillette, R.; Liebman, J.; Sellman, A.; Wyse, A. Social Impact Bonds: Lessons learned so far. Community Dev. Invest. Rev. 2013, 9, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomantonio, C. Setting realistic expectations: The narrow use-case for Social Impact Bonds. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 2018, 3, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S.; Cordes, J.J.; Pandey, S.K.; Winfrey, W.F. Use of social impact bonds to address social problems: Understanding contractual risks and transaction costs. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2018, 28, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, P.T. An Institutional Theory of Public Contracts: Regulatory Implications (No. w14152); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, P.T. A Tribute to Oliver Williamson: Regulation: A Transaction Cost Perspective. Calif. Manag. 2010, 52, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, N.; Sinclair, S.; Roy, M.; Huckfield, L.; Donaldson, C. Social impact bonds: A wolf in sheep’s clothing? J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2013, 21, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstetter, L.; Lehner, O.M. Opening the Market for Impact Investments: The Need for Adapted Portfolio Tools. Entrep. J. 2015, 5, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.; Young, J.; Barnett, C. Impact Investments: A literature Review; Centre for Development Impact: Brighton, UK, 2015; Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/ds2/stream/?#/documents/29293/page/1 (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Wilson, K.E.; Silva, F.; Ricardson, D. Social Impact Investment: Building the Evidence Base. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2562082 (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Glynn, J.J.; Murphy, M.P. Public management: Failing accountabilities and failing performance review. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 1996, 9, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiatycki, M.; Farooqi, N. Value for money and risk in public–private partnerships: Evaluating the evidence. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M.K. Are public private partnerships value for money? Evaluating alternative approaches and comparing academic and practitioner views. Account. Forum 2005, 29, 345–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carè, R. Social Impact Bond: Beyond Financial Innovation. In Sustainable Financial Innovation; Wendt, K., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Visconti, R.M. Multidimensional principal–agent value for money in healthcare project financing. Public Money Manag. 2014, 34, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease and Control Prevention (CDC). Pay for Success: How-to Guide for Local Government Focused on Lead-Safe Homes. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/docs/pay_for_success_guide.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Schinckus, C. The valuation of social impact bonds: An introductory perspective with the Peterborough SIB. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. J. Bus. 2002, 55, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Reconstructing grounded theory. In The Sage Handbook of Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine Publishing Company: Hawthorne, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, L.M. Case Study Research and Theory Building. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2002, 4, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynham, S.A. Theory building in the human resource development profession. Hum. Dev. Q. 2000, 11, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, J. Building operations management theory through case and field research. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Wang, J.-D.; Huang, Y.-X. Health expenditures spent for prevention, economic performance, and social welfare. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nag, R.; Gioia, D.A. From Common to Uncommon Knowledge: Foundations of Firm-Specific Use of Knowledge as a Resource. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 421–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, A. A Health Outcomes Fund for Canada. How Paying for Outcomes Could Improve Health and Deliver Better Value for Money. MaRS Centre for Impact Investing. Available online: https://www.marsdd.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/A-Health-Outcomes-Fund-for-Canada.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Rizzello, A.; Caridà, R.; Trotta, A.; Ferraro, G.; Carè, R. The Use of Payment by Results in Healthcare: A Review and Proposal. In Social Impact Investing Beyond the SIB; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 69–113. [Google Scholar]

- MaRS. Pionering Pay-for-Success in Canada. A New Way to Pay for Social Progress. Available online: https://www.marsdd.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/MaRS-Pioneering-Pay-For-Success-In-Canada-Oct2016.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- MaRS. Impact Report. Available online: https://www.marsdd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/MaRS_Impact_Report_2018.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Ryan, S.; Young, M. Social impact bonds: The next horizon of privatization. Stud. Political Econ. 2018, 99, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges Ventures. Ways to Wellness SIB. Available online: https://www.bigsocietycapital.com/file/1639/download?token=CqYjHZf_ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Commissioning Better Outcomes (CBO). Ways to Wellness Social Impact Bond: The UK’s First Health SIB. Ways to Wellness Deep Dive Report. Available online: https://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/-/media/Files/Programme%20Documents/Commissioning%20Better%20Outcomes/CBO_ways_to_wellness_report.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Commissioning Better Outcomes (CBO). Update Report. Available online: https://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/-/media/Files/Programme%20Documents/Commissioning%20Better%20Outcomes/CBO%20Update%20Report_Full%20Report.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Tan, S.; Fraser, A.; Giacomantonio, C.; Kruithof, K.; Sim, M.; Lagarde, M.; Disley, E.; Rubin, J.; Mays, N. An Evaluation of Social Impact Bonds in Health and Social Care: Interim Report. Available online: https://piru.lshtm.ac.uk/assets/files/Trailblazer%20SIBs%20interim%20report%20March%202015,%20for%20publication%20on%20PIRU%20siteapril%20amendedpdf11may.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- GoLab. Mental Health and Employment Partnership (Staffordshire, Haringey & Tower Hamlets). Available online: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge/case-studies/mhep/pdf/ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- MHEP, Mental Health and Employment Partnership. Mental Health and Employment Partnership. In Depth Review. Available online: https://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/-/media/Files/Programme%20Documents/Commissioning%20Better%20Outcomes/comissioning_better_outcomes_in_depth_review.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Commissioning Better Outcome (CBO). Reconnections Social Impact Bond: Reducing Loneliness in Worcestershire. An In-Depth Review. Available online: https://www.bigsocietycapital.com/sites/default/files/attachments/CBO_In-Depth%20Reviews_Reconnections.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Gustafsson-Wright, E.; Gardiner, S.; Putcha, V. The Potential And Limitations Of Impact Bonds: Lessons from the First Five Years of Experience Worldwide; Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agapitova, N.; Sanchez, B.; Tinsley, E. Government Support to the Social Enterprise Sector: Comparative Review of Policy Frameworks and Tools. Available online: https://www.innovationpolicyplatform.org/system/files/SE%20Policy%20Note_Jun20.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- Government of Canada. The Next Phase of Canada’s Economic Action Plan: A Low-Tax Plan for Jobs and Growth. News Release, 7 June 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2011/06/government-canada-reintroduces-next-phase-canada-economic-action-plan-low-tax-plan-jobs-growth.html(accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Government of Ontario. Piloting Social Impact Bonds in Ontario: The Development Path and Lessons Learned. 12 November 2015. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/piloting-social-impact-bonds-ontario-development-path-and-lessons-learned (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Government of Alberta. Putting Alberta’s Growing Savings to Work for Our Future. News Release, 4 March 2014. Available online: https://www.farmingsmarter.com/putting-albertas-growing-savings-work-future/(accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Department of Finance—Canada. The Next Phase of Canada’s Economic Action Plan: A Low-Tax Plan for Jobs and Growth. Department of Finance, Canada. Available online: https://budget.gc.ca/march-mars-2011/plan/Budget2011-eng.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Echenberg, H. Government of Canada and Social Finance. Available online: https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/PublicWebsite/Home/ResearchPublications/BackgroundPapers/PDF/2015-140-e.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- Albertson, K.; Fox, C. Payment by Results and Social Impact Bonds: Outcome-Based Payment Systems in the UK and US; Policy Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- HM Government. Growing the Social Investment Market: A Vision and Strategy; HM Government: London, UK, 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61185/404970_SocialInvestmentMarket_acc.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Big Lottery Fund. About Commissioning Better Outcomes and the Social Outcomes Fund. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/261051/CBO_guide.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Cooper, C.; Graham, C.; Himick, D. Social impact bonds: The securitization of the homeless. Account. Organ. Soc. 2016, 55, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; McHugh, N.; Roy, M.J. Social innovation, financialisation and commodification: A critique of social impact bonds. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, A.E.; Warner, M.E. The razor’s edge: Social impact bonds and the financialization of early childhood services. J. Urban Aff. 2018, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giantris, K.; Pinakiewicz, B. Pay for success: Understanding the risk trade-offs. Community Dev. Invest. Rev. 2013, 9, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Child, C.; Gibbs, B.G.; Rowley, K.J. Paying for success: An appraisal of social impact bonds. Glob. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2016, 21, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SIB Name | Country | Healthcare Issues | Target Population | Launch Date | Capital Raised |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Hypertension Prevention Initiative | Canada | Hypertension | 7000 prehypertensive older adults (60+) in Toronto and Vancouver. | October 2016 | C$2 M |

| Mental Health and Employment Partnership | UK | Mental health and employment | 2500 people with severe mental illness (typically with a diagnosis of psychosis, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression or anxiety) currently in contact with statutory mental health services. | January 2016 | £0.4 M |

| Reconnections | UK | Social isolation | At least 3000 people aged 50 years and over classified on the UCLA loneliness scale (a common loneliness measure) as 8 to 12 (though it is expected that most clients will be 65+). | July 2015 | £0.85 M |

| Ways to Wellness | UK | Social prescribing | 11,000 people with long-term health conditions such as lung disease, diabetes and asthma. | March 2015 | £1.7 M |

| Outcome Founder | Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) |

| Service Provider | Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada |

| Independent evaluator | The Social Research and Demonstration Corporation |

| Investors | Foundations, high-net-worth individuals, and companies |

| Project development & performance advisor | MaRS Centre for Impact Investing |

| Legal advisor | Miller Thomson LLP |

| Commissioner | Newcastle Gateshead CCG (the CCG) |

| Outcome payers | Newcastle Gateshead CCG (the CCG), Big Lottery Fund, Commissioning Better Outcomes (CBO) Fund, and the Cabinet Office’s Social Outcomes Fund (SOF) |

| Service Provider | Lead service provider: Ways to Wellness Subcontractors: First Contact Clinical, Mental Health Concern, Healthworks Newcastle, Changing Lives |

| Investment manager | Bridges Fund Management |

| Investors | Bridges Fund Management through its Social Impact Bond and Social Entrepreneurs Fund |

| Intermediaries/consultancies | Social Finance UK, Rocket Science, NHS North East Quality Observatory System (NEQOS), Vital Services North East |

| Commissioners | Staffordshire County Council, London Borough of Haringey, Tower Hamlets Clinical Commissioning Group, Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund, Social Outcomes Fund |

| Intermediary | Social Finance (model development and contract management) |

| Investor | Big Issue Invest |

| Successful Engagement of Users | Job Entry Outcome | Job Sustainment Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (<16 Hours/Week) | (>16 Hours/Week) | (<16 Hours/Week) | (>16 Hours/Week) | ||

| Outcome payment | £790–£1000 | £700 | £1350 | £1400 | £1650 |

| Payment made by | MHEP/Big Issue Invest (20%) Commissioner (70%) Social Outcome Fund/Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund (10%) | Social Outcome Fund/Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund (100%) | Social Outcome Fund/Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund (100%) | Social Outcome Fund/Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund (100%) | Social Outcome Fund/Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund (100%) |

| Commissioners | Worcestershire County Council Clinical Commissioning Groups (South Worcestershire CCG, Redditch and Bromsgrove CCG and Wyre Forest CCG) |

| Service provider | Lead service provider: Age UK Herefordshire and Worcestershire Subcontracted service providers: Age UK Herefordshire and Worcestershire, Age UK Malvern, Onside Advocacy, Rooftop, Simply Limitless, Worcester Community Trust |

| Intermediary | Social Finance |

| Investor | Care and Wellbeing Fund Nesta Impact Investments Age UK |

| Fund | Description |

|---|---|

| Social Outcomes Fund and Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund (Cabinet Office and Big Lottery Fund) | The Social Outcomes Fund (£20 m) and Commissioning Better Outcomes (£40 m) were established by the Cabinet Office and the Big Lottery Fund with the aim to support the development of SIBs in policy areas by providing support/funding in the development stage and by paying for a part of the outcomes payments. Commissioning Better Outcomes was been set up by the Big Lottery Fund. The Social Outcomes Fund is a Government (Cabinet Office) funded initiative. |

| Life Chances Fund (Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) | The Life Chances Fund provides support for locally commissioned SIBs that tackle complex social issues and have been committed by central government to contribute to outcome payments for payments by results (PbR) schemes which involve socially minded investors. The LCF will aim for contributions of around 20 per cent of total outcomes payments, with local commissioners paying for the majority of the outcomes payments. |

| Youth Engagement Fund (Department for Work and Pensions) | The Youth Engagement Fund is a £16 million PbR fund that was established by DWP and the Cabinet Office to help disadvantaged young people aged 14 to 17 to participate and succeed in education or training. |

| Fair Chance Fund (Department for Communities and Local Government and Cabinet Office) | The Fair Chance Fund is used to fund seven Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) focused on improving outcomes for young homeless people. |

| The Rough Sleeping SIB Fund (Department for Communities and Local Government) | The fund aims to help long-term rough sleepers with complex needs over 3 years: 2016 to 2017, 2017 to 2018, and 2018 to 2019. |

| Innovation Fund (Department for Work and Pensions) | The Innovation Fund (IF) pilot was delivered between April 2012 and November 2015 to support young people aged 14 or over who were considered disadvantaged or at risk of disadvantage. The IF pilot was comprised of ten projects, which were commissioned in two rounds. |

| Project | Intervention Area | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Sandwell and Birmingham | End of life services | Not commissioned. |

| Cornwall | Frail older people with LTCs at risk of emergency admission | Not commissioned. |

| East Lancashire | Isolation, unemployment and poor quality of life | Not commissioned (the service has been funded outside a PbR scheme). |

| Leeds | Nursing care for people with neurological trauma | Not commissioned. |

| Manchester | Behavioral interventions for children | In progress. |

| Newcastle | Better self-management of long-term conditions through social prescribing | In progress. |

| Shared Lives | Alternative to care homes for people in need for intensive support | Two SIBs were signed and are under development in Lambeth and Manchester (from 2015), and Haringey and Thurrock (from 2017). |

| Thames Reach | Personalized service pathway for homeless | In progress. |

| Worcester | Loneliness among older people through tailored support | In progress. |

| H&S HIB | Ways to Wellness HIB | Mental Health & Employment HIB | Reconnection HIB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractual model | Two different contracts and presence of a trustee | Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) | (a) Social Investment Partnership (SIP) model, (b) Different local business models. | Special purpose vehicle (SPV) owned by the investors. |

| Project commissioner | Public Health Agency | The HIB has been commissioned by Newcastle Gateshead CCG (the CCG) that received from Big Lottery Fund, Commissioning Better Outcomes (CBO) Fund and the Cabinet Office’s Social Outcomes Fund (SOF) ‘top-up’ payments to help cover some of the outcome payments. | Different local public authorities. | The Reconnections deal is characterized by the presence of a primary commissioner (Worcestershire County Council) and three co-commissioners (Clinical Commissioning Groups, CCGs) that help to ensure a joined up and multiagency approach. |

| Collaboration between different public authorities | The project was developed at the federal level around the collaboration between the Public Health Agency and the Heart and Stroke Foundation. | The deal is developed around the collaboration between a local authority and the outcome funds. | The deal is developed around the collaboration between local and central authorities. | The deal is developed around the collaboration between a local authority with three co-commissioners. |

| Predefined level of public savings | (a) The deal is not related to a predefined level of public savings. | (a) The deal is related to a predefined level of public savings. | (a) The deal is related to a predefined level of public savings. | (a) The deal is related to a predefined level of public savings. |

| Financial advisor | MaRS (model development and contract management). | Social Finance UK (model development and contract management). | Social Finance UK (model development and contract management). | Social Finance UK (model development and contract management). |

| Investors | Businesses, charitable foundations, and wealthy individuals. | Bridges Fund Management. | Big Issue Invest. | Care and Wellbeing Fund; Nesta Impact Investments; Age UK. |

| Rate of return |

|

| Data not provided/unconfirmed. | Data not provided/unconfirmed. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carè, R.; De Lisa, R. Social Impact Bonds for a Sustainable Welfare State: The Role of Enabling Factors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102884

Carè R, De Lisa R. Social Impact Bonds for a Sustainable Welfare State: The Role of Enabling Factors. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102884

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarè, Rosella, and Riccardo De Lisa. 2019. "Social Impact Bonds for a Sustainable Welfare State: The Role of Enabling Factors" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102884

APA StyleCarè, R., & De Lisa, R. (2019). Social Impact Bonds for a Sustainable Welfare State: The Role of Enabling Factors. Sustainability, 11(10), 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102884