1. Introduction

Enterprise social media (ESM) is a special type of electronic media based on the Internet and the technological foundations of Web 2.0 [

1,

2]. Recent research by McKinsey Global Institute found that workers’ productivity can increase 20–25% by using social media technologies within and across organizations, which could contribute 900 billion to 1.3 trillion dollars in annual value to the U.S. economy [

3]. Aware of the benefits that ESM brings to their companies and employees, more and more organizations have implemented ESM platforms [

4]. The widespread use of ESM has piqued the interests of many researchers. For instance, recent studies find that these platforms promote communication [

5,

6] and organizational knowledge sharing [

4,

7,

8] among employees. Further exploring the advantages of ESM, scholars in related fields consider that ESM is conducive to enhancing the social network [

9,

10,

11] and social capital [

7,

12,

13] of employees.

Thriving at work is considered as an employee’s perception of learning and vitality [

14]. Prior studies have revealed the significant correlation between thriving at work and various desirable individual and organizational outcomes, such as job performance, employee sustainability, and organizational citizenship behavior [

15,

16,

17], considering the increasingly fast-paced, complex, and competitive environment in organizations [

18]. However, very little research has been conducted with respect to effectively developing employees’ thriving at work [

17], particularly in the context of social media. Reviewing previous research, we find that the relationship between ESM usage (particularly its use for work-related purposes) and thriving at work is still unclear and full of controversies. On the one hand, numerous studies show that the use of ESM promotes communication and helps employees gain knowledge [

8,

19,

20,

21], contributing to their learning [

14]. The broad information resource shared in ESM [

11,

19] can enhance the vitality of employees [

14] by establishing trust among employees [

12]. One the other hand, some studies have also found that the use of ESM may also lead to information and communication overload, hindering the exchange of knowledge [

5,

8], which is not conducive to knowledge acquisition. Some studies have argued that using social media may lead to social overload and even task overload, which will induce emotional exhaustion and strain [

22,

23,

24] and negatively affect vitality [

25]. The divergence in prior studies demonstrates a need for further investigating the underlying mechanisms of the influence of ESM on thriving in different contexts.

Guanxi is an important factor affecting the relationship between ESM’s use and thriving at work, particularly due to the special environment in China. Some studies indicate that the relationship among employees is a key factor influencing their thriving at work [

14]. Individuals with good guanxi with colleagues have the access to more knowledge [

26], which facilitates their learning [

14]. Individuals who maintain good relational resources always possess higher energy than those without [

14,

17]. Especially, ESM enables employees to connect with more people and build relationships with them [

11,

19], developing a basis for forming a good relationship.

Newcomers in an organization are typically not well acquainted with the entire company and colleagues when they start their new positions. Therefore, we introduce “swift guanxi”, which is referred to as newcomer’s perception of an interpersonal relationship established quickly with veterans [

27] to study the relationship between ESM usage and thriving at work. In particular, focusing on newcomers in our research, we attempt to explore how their work-related use of ESM affects their thriving at work through the swift-guanxi perspective.

Our study makes several significant contributions to the existing literature about ESM. Firstly, we examine the influence of work-related use of ESM on newcomers’ thriving at work from the perspective of swift guanxi, and our findings help manager better understand the impact of ESM on newcomers’ thriving at work, either as a facilitator or as an inhibitor. Second, our study enriches the existing research of thriving in the workplace by analyzing the role of work-related ESM usage. Although the value of thriving at work is widely acknowledged, there is limited effort to improve this line of research, especially in terms of its linkage to ESM with a focus on newcomers. Third, introducing and extending the concept of swift guanxi from its primary field in social commerce, our research proposes an innovative perspective to study the relationship between the thriving of newcomers and their use of ESM in workplaces and tests its mediating effect.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews prior literature on ESM, thriving at work, and swift guanxi.

Section 3 demonstrates our hypotheses and research model.

Section 4 presents our research method, the sample and data collection, and sample demographic information.

Section 5 summarizes the analysis and results of our research.

Section 6 discusses results and highlights the theoretical and managerial implications of our research. The last section concludes the paper with limitations and future research direction.

3. Hypothesis Development and Model

Mutual understanding means understanding each other’s needs or views [

27]. Publicly presenting the information that users share on the platform is considered one of the most basic capabilities of social media, that is to say, any content posted by employees on the platform can be easily viewed and searched by other colleagues in the organization [

28]. Newcomers may encounter various difficulties with their jobs in the new environment. They can use ESM to express their concerns, which helps veterans understand their needs so they can provide guidance timely. At the same time, the accuracy of newcomers’ meta-knowledge (knowledge of “who knows what” and “who knows whom”) can be increased through the use of ESM at work [

11], which enables newcomers to better understand their new organizations and colleagues. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Newcomers’ work-related use of ESM positively affects the mutual understanding between newcomers and colleagues.

Reciprocal favors refer to the positive benefits that can be derived from the interactions between newcomers and veterans [

46,

54,

55,

56]. When newcomers use ESM for work-related purposes, such as sharing their expertise in a particular area through ESM, colleagues may ask for relevant help when they face problems at work. Generally speaking, newcomers who share useful knowledge with their colleagues not only help them solve work problems but also impress their co-workers with the expertise and skills they possess, so newcomers’ use of ESM for knowledge sharing can bring reciprocal favors [

57]. Moreover, as organizational entry is a special period full of uncertainty for newcomers, they always tend to seek various useful information and resource in the organization for accelerating socialization [

28]. Hence, the process of socialization will be facilitated when newcomers use ESM to connect with colleagues with specific competencies or to obtain key resources in the organization. Such a type of socialization is beneficial for organizations, colleagues, as well as newcomers. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. Newcomers’ work-related use of ESM positively affects reciprocal favors between newcomers and colleagues.

Relationship harmony is commonly referred to as mutual respect and conflict avoidance [

27]. Newcomers have to take much time to adapt to their new organization and their own work. When newcomers are not certain about their tasks, they can use the ESM’s feature of “tasks” to check their work. When newcomers understand their roles, they will experience a higher level of clarity to minimize conflicts with colleagues [

58]. Moreover, the work today in an organization usually requires cooperation between different colleagues or different departments. In order to complete the task successfully, employees need to know their co-workers’ work progress in a timely manner. ESM enables employees to improve the visibility organizational activities [

28]; when newcomers post updates on work projects by using ESM, their work progress can be easily and timely recognized by their colleagues, helping to avoid work inconsistencies and reduce conflicts between newcomers and co-workers. Some studies, such as Dimicco et al. [

59], also mention that the use of social media at work can increase employees’ attachment to the organization by allowing them to make and maintain friendships at work, facilitating the formation of harmonious relationships. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. Newcomers’ work-related use of ESM positively affects relationship harmony between newcomers and colleagues.

The concept of learning belongs to the cognitive dimension of psychological experience, conceptualized as the feeling that a person is getting and also able to apply knowledge and skills [

14]. When individuals capture this feeling of learning, they are more likely to be physically healthy. In contrast, vitality belongs to the affective dimension of psychological experience, measuring the positive feeling of individuals when they are energetic [

14]. A sense of vitality helps individual maintain mental health, so depression will be less likely [

60]. At the beginning of entry, newcomers may find it hard to adapt to their new organizations and work because of their unfamiliarity. The use of ESM can promote mutual understanding (e.g., understanding each other’s needs or views) between newcomers and colleagues. When newcomers encounter issues at work, veterans can provide effective help (e.g., information or skills) to foster their learning as veterans understand the needs of newcomers. In addition, the timely and effective support provided by the veterans also allows newcomers to focus more on their work because they will need less time and energy to find solutions to address the issues with the help from veterans. Spreitzer et al. [

14] find that employees, who immersed in their work are more likely to finish tasks efficiently and effectively, which contributes to learning. When employees concentrate on their own works, they will be absorbed in their work and become energized [

61] and, thus, complete their tasks successfully. Consequently, they will tend to possess a sense of accomplishment, full of energy [

14]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4. The mutual understanding between newcomers and colleagues positively affects newcomers’ learning.

Hypothesis 5. The mutual understanding between newcomers and colleagues positively affects newcomers’ vitality.

Social exchange theory believes that reciprocal favors are the premise of exchange behavior; once the exchange parties do not perceive the benefits of the exchanges to each other, these exchanges will stop immediately [

62]. Based on the social exchange theory, when newcomers and veterans perceive reciprocal favors at work, they are more likely to exchange resources, such as information, knowledge, or reputation, with each other. These resources often help newcomers complete their tasks better, further facilitating their learning and vitality. In other words, when newcomers and their colleagues both recognize the benefits of newcomers’ use of ESM, they will be willing to use ESM more actively at work and engage in social interactions or cooperation to gain more benefits from each other. In this way, newcomers will receive more resources from organizations, including knowledge, information, positive emotional resources, and relationship resources [

28], which helps their desire to learn. Prior studies [

14] show that social interactions with colleagues at work arouse employees’ feeling of learning. Resources, such as knowledge and skills, also enable newcomers to perceive vitality and accomplishment by helping them better cope with their tasks [

14,

25]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6. The reciprocal favors between newcomers and colleagues positively affect newcomers’ learning.

Hypothesis 7. The reciprocal favors between newcomers and colleagues positively affect newcomers’ vitality.

The concept of relationship harmony means the respect and conflict avoidance between each other [

27]. Harmonious relationships enable colleagues to cooperate or help each other at work, so newcomers can acquire skills, knowledge, and experience from veterans to successfully complete their work. Additionally, effective work handing increases energy of newcomers by empowering their sense of accomplishment [

14]. Moreover, relationship harmony means mutual respect between newcomers and veterans. Many studies have shown that mutual respect among employees helps promote thriving. Learning and experimentation with new behavior will be facilitated when employees feel safe in an environment with mutual respect [

25,

63,

64]. In addition, when individuals and colleagues respect each other, they are more likely to believe that they are worthy and valued organizational members [

14], which facilitates a sense of relatedness as individuals feel more connected to others [

65]. This sense of relatedness may further increase vitality and openness to learning because such sense may spark feelings of positive emotion and unleash the broaden-and-build model [

25,

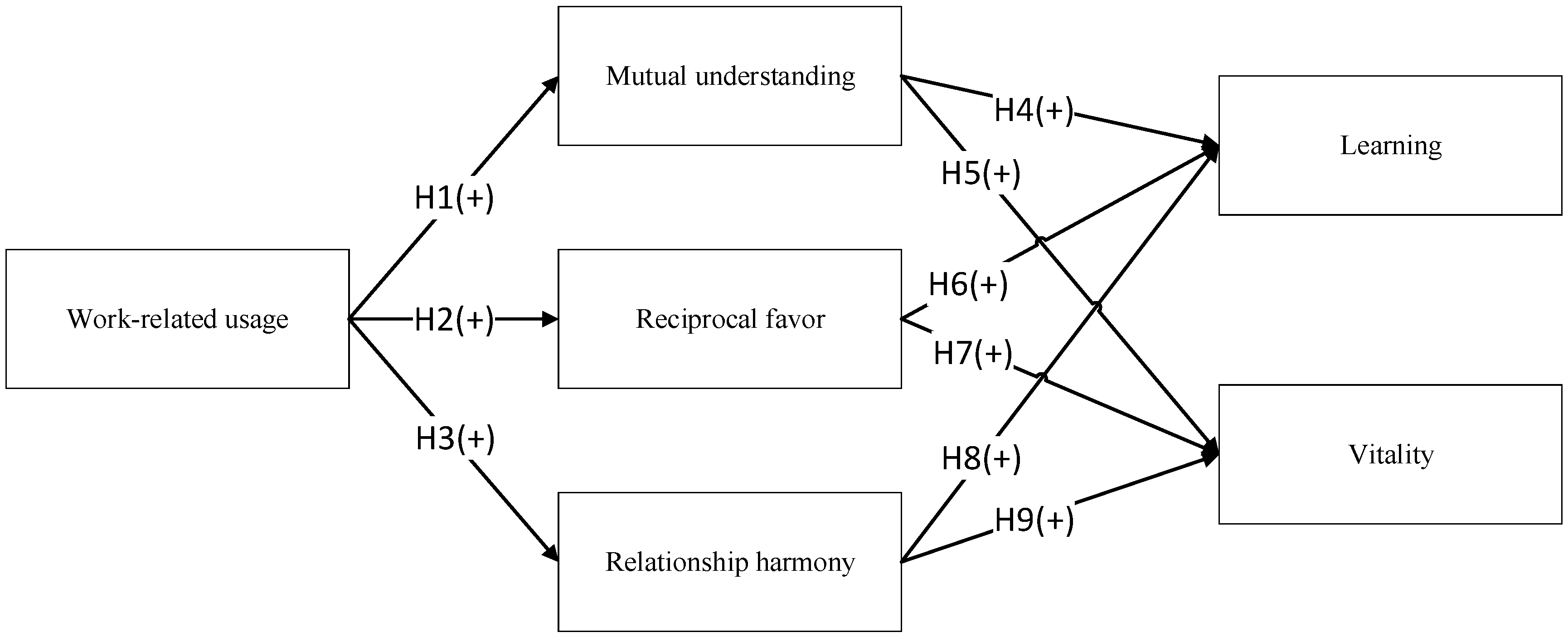

66]. Therefore, we propose Hypotheses 8 and 9. The theoretical model is exhibited in

Figure 1.

Hypothesis 8. The relationship harmony between newcomers and colleagues positively affects newcomers’ learning.

Hypothesis 9. The relationship harmony between newcomers and colleagues positively affects newcomers’ vitality.

6. Discussion

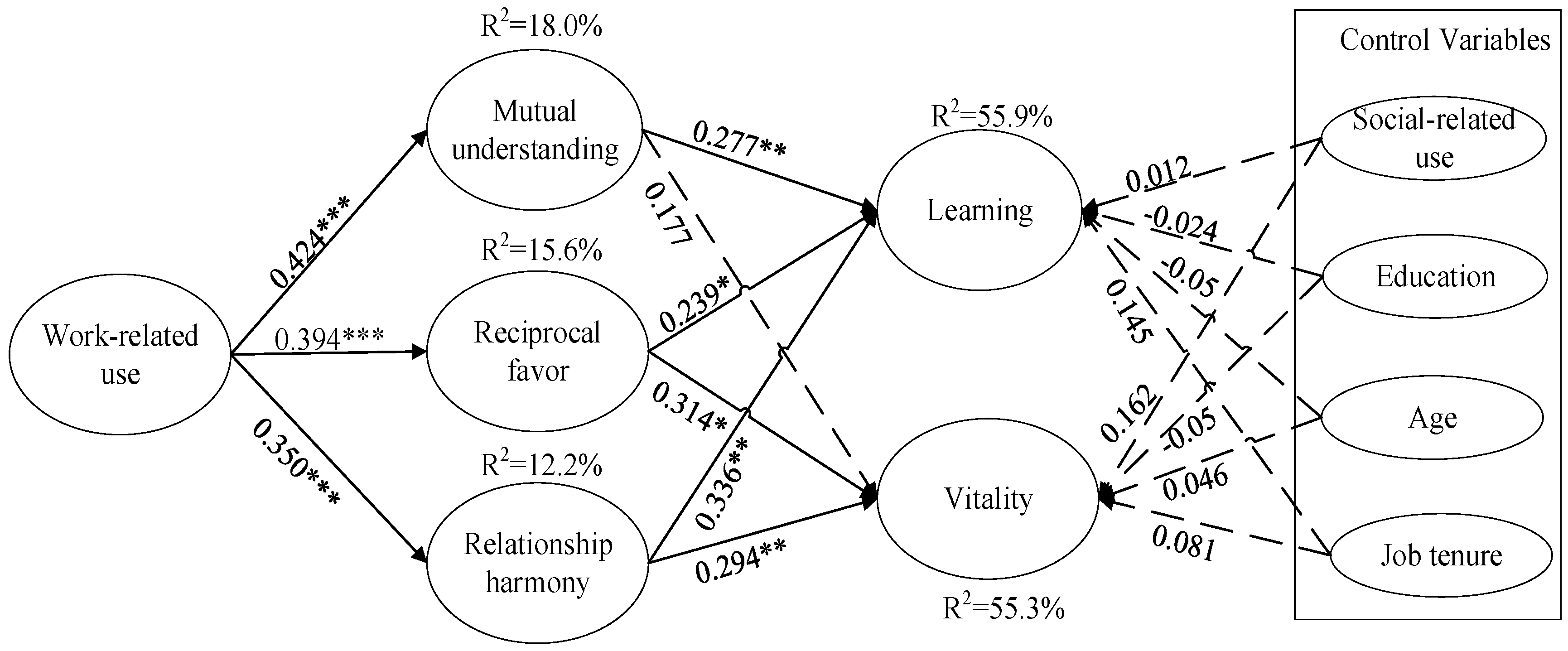

6.1. Discussions

The study explores the relationship between newcomers’ work-related use of ESM and their thriving (i.e., learning, vitality) at work through adopting and extending the concept of swift guanxi. Most of our hypotheses are supported by our empirical analysis. First, the concept of newcomers’ work-related use of ESM plays a positive role on mutual understanding, reciprocal favors, and relationship harmony. Second, reciprocal favors and relationship harmony both have a positive effect on newcomer learning, as well as vitality. Furthermore, mutual understanding significantly facilitates the learning of newcomers.

However, mutual understanding between newcomers and veterans does not significantly promote the vitality of newcomers. As Spreitzer et al. [

14] suggest, individuals feel vital only when they have enough energy. However, because of their unfamiliarity with new jobs, newcomers have to take a great deal of time and energy to understand the task-related views and knowledge shared in ESM by veterans. The more knowledge and skills newcomers are exposed to, the more energy they need to consume to master the new knowledge. Although the acquisition of new knowledge and skills promotes the learning of newcomers, the vitality of newcomers may decrease with energy consumption.

Among the six mediating paths, five of them were proved to be fully mediation. Specifically, the relationship between newcomers’ work-related use of ESM and their vitality was mediated by mutual understanding, reciprocal favors, and relationship harmony, and the relationship between newcomers’ work-related use of ESM and their learning was mediated by mutual understanding as well as reciprocal favors. The results suggest that the formation of swift guanxi between newcomers and veterans has a positive effect on newcomers’ work-related use of ESM and their vitality. Furthermore, the formation of mutual understanding and reciprocal favors between newcomers and veterans also positively affects newcomers’ work-related use of ESM and their learning. That is, as newcomers and veterans establish swift guanxi through using ESM for work, they will feel a sense of energy and accomplishment of acquiring and mastering knowledge and skills.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

Our research has several major implications for extant literature. First, the existing research on the thriving at work seldom considers the impact of information technology. Our research explores the effects of ESM on thriving at work from the perspective of swift guanxi, which enriches our understanding about employees’ thriving, especially the impact of information technology on thriving at work. Specifically, newcomers’ use of ESM for work-related purpose can effectively promote their perception of learning and vitality through establishing reciprocal favors and harmonious relationship with veterans. In addition, newcomers’ perceptions of learning will increase when they establish mutual understanding with veterans through the use of ESM.

Second, this research extends the literature on the value of ESM. Previous empirical studies on ESM mainly focus on how ESM affects organizational knowledge transfer [

7,

83,

84] and employee performance [

85,

86], but very few have considered an employee’s psychological state. Our study addresses this research gap by adopting a guanxi perspective to explore how ESM affects employees’ psychological state—thriving at work. Our results provide additional insights about the value ESM creates for organization.

Third, we study the special target group of newcomers, which is different from previous studies that focus mainly on the group of veterans, but very little on organizational newcomers and their IT usage. Our research has effectively extended current research by exploring the relationship between newcomers’ work-related use of ESM and their thriving. Furthermore, applying the concept of swift guanxi from the field of social commerce to organization and management, we investigate and reveal the influencing mechanism of the use of ESM on newcomers’ thriving at work. Our research provides promising directions for further research on IT use and employees’ thriving.

6.3. Managerial Implications

Revealing the role of ESM in enterprises and employees, our research provides some important guidelines for both organizational managers and employees. First, we suggest managers to encourage newcomers to interact with veterans through ESM to promote mutual understanding. Similarly, organizational managers can also offer some incentives or regulations to encourage veterans to actively understand the ideas and views of newcomers, for example, encouraging veterans to pay more attention to the work status of newcomers and sharing knowledge related to newcomers in ESM to help them solve their work problem quickly. In this way, newcomers’ thriving at work can be effectively enhanced, helping them better adapt to the new organization and achieve better development.

Second, we strongly recommend that managers encourage team activities or collaboration in ESM to cultivate the team awareness between newcomers and veterans, which helps promote a sense of reciprocal favors among them. Managers can promote collaboration between newcomers and veterans by assigning them some interdependent tasks based on their expertise, which will not only help the newcomers learn more skill or knowledge, but also increase their energy at work. Furthermore, we also suggest that managers encourage newcomers to post the issues they encounter in workplace by using ESM to seek advice from their colleagues. This type of interaction between newcomers and veterans is conducive to social exchanges that promote reciprocal favors and develop thriving at work.

Third, managers should consider building harmonious relationships between newcomers and veterans through the use of ESM, for example, encouraging newcomers and veterans to use some of the ESM features such as “liking” and “comments” to express gratitude after getting help from each other. A harmonious relationship will help newcomers sustain their learning and acquire more resources from veterans to boost their vitality.

In summary, current research of ESM has not adequately explored the use of ESM to facilitate newcomers’ thriving at work, which we have addressed in this paper. Our findings indicate that managers need to take appropriate measures to leverage ESM to form swift guanxi between newcomers and veterans and, thus, help newcomers to learn and enhance vitality in workplace.

7. Conclusions

The rapid development of information technology and the Internet in the past decade has dramatically changed the business environment [

87]. Social media, as a result of such development, is regarded as a major impetus revolutionizing the ways of communication among organizations and individuals. On the one hand, organizations use social media to improve their relationship with consumers and attract new clients [

88] and also improve the company’s profitability or innovation performance. On the other hand, employees within organizations also use social media to achieve positive outcomes by improving interpersonal relationships and increasing access to resources [

1,

4,

11,

19]. Our research focuses on the impact of social media on individual employees. Specifically, we explore the impact of ESM on the employees’ thriving at work by focusing on the special target group of newcomers. Adopting the concept of swift guanxi, our research findings suggest that newcomers work-related use of ESM will actively promote the formation of swift guanxi between them and veterans, thus developing their thriving at work.

Although our research makes significant contributions, we would also like to acknowledge some of the limitations in our study for possible directions of future research. First, given the long track time needed and the limited number of newcomers, we have to admit that our research sample size is small. Future studies will need to test large samples to improve the statistical power. Moreover, our research samples were all collected from the technology department, which led to the majority of the subjects in our sample being male, where women only accounted for a small percentage. This test sample is likely to lead to bias in our findings. Therefore, we call for future research to involve different departments while balancing the gender of participants.

Second, we only considered the work-related use of ESM in our study but ignored the social-related use. Many studies have found the important value of social-related use of ESM [

12], especially for newcomers [

32]. Therefore, we suggest that future research should also focus on the impact of social-related use of ESM on employees’ thriving.

Finally, the target group of this study is newcomers, while the effect of ESM on thriving at work of veterans has not been investigated. We believe that it is necessary and valuable to further study the impact of ESM on the thriving at work of veterans, which will enable us to understand the value of ESM more clearly and to better facilitate employees’ growth.