A Journey of Self-Reflection in Students’ Perception of Practice and Roles in the Profession

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Research Methodology

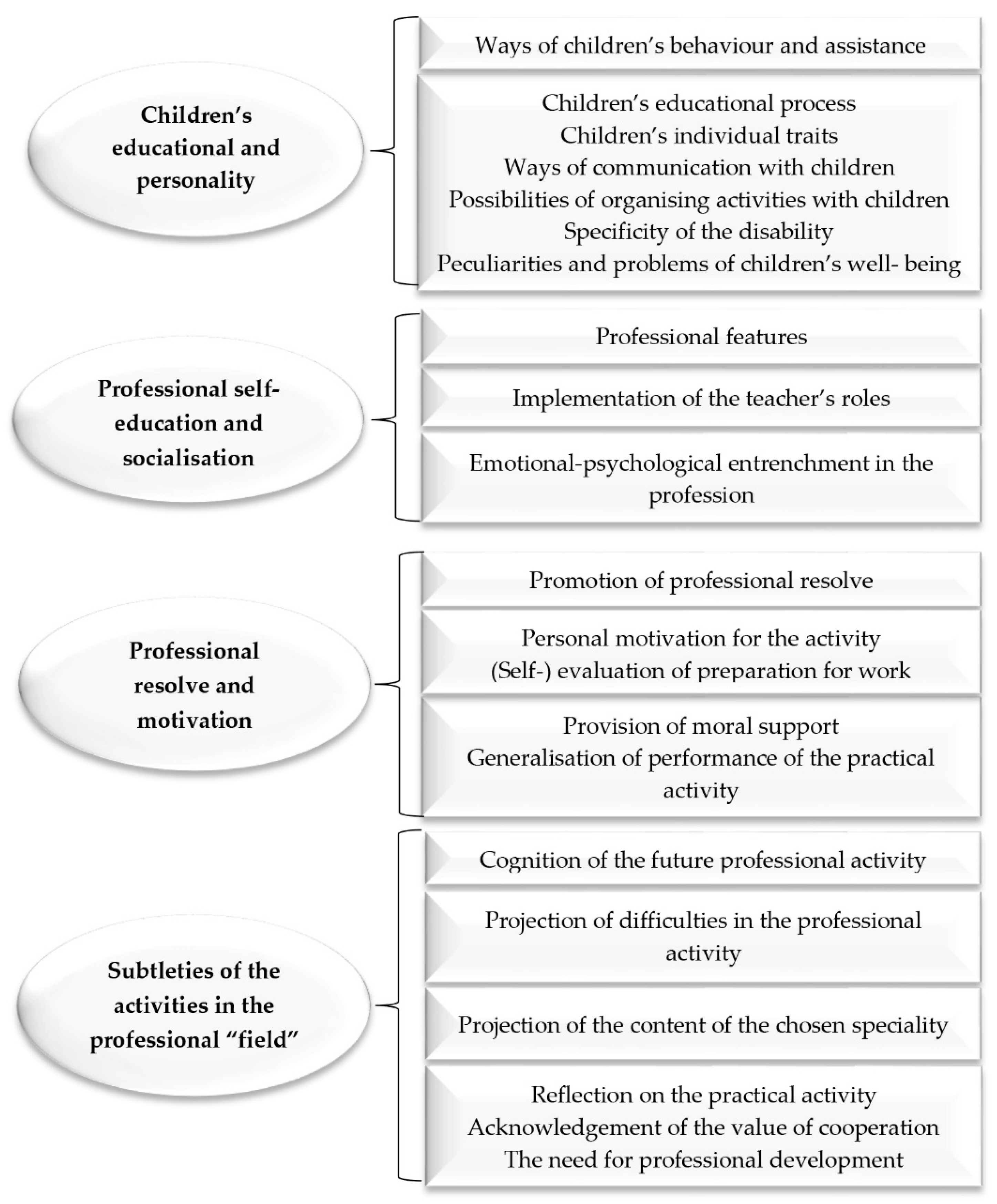

3. Results

3.1. The First Dimension

3.2. The Second Dimension

3.3. The Third Dimension

3.4. The Fourth Dimension

3.5. The Content of the Fifth Dimension

3.6. The Sixth Dimension

3.7. The Seventh Dimension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Education 2030. Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action. Towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Lifelong Learning for All. Paris, UNESCO2016. Available online: http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/incheon-framework-for-action-en.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2018).

- Education Transforms Lives. UNESCO (2017). Paris. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002472/247234e.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2018).

- Education for Sustainable Development Goals Learning Objectives, 2017. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2018).

- The Competences in Education for Sustainable Development. Learning for the future: Competences in Education for Sustainable Development United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Steering Committee on Education for Sustainable Development. 2012. Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/esd/ESD_Publications/Competences_Publication.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Rogers, R. Reflection in Higher Education: A Concept Analysis. Innov. Higher Educ. 2001, 26, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velzen, J.H. Are Students Intentionally Using Self-reflection to Improve how they Learn? Reflective Pract. 2015, 16, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, S.; Clayton, P.H. Generating, Deepening, and Documenting Learning: The Power of Critical Reflection in Applied Learning. J. Appl. Learn. Higher Educ. 2009, 1, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M. The Pedagogical Balancing Act: Teaching Reflection in Higher Education. Teach. Higher Educ. 2013, 18, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, J.M. Reflective Teaching and Learning: Why We Should Make Time to Think. Teaching Innovation Projects 2014, 4. Available online: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/tips/vol4/iss2/7 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Wong, A.C.K. Considering Reflection from the Student Perspective in Higher Education. SAGE Open. 2016. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244016638706 (accessed on 26 October 2018).

- Korthagen, F.A.J.; Vasalos, A. Levels in Reflection: Core Reflection as a Means to Enhance Professional Growth. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2005, 11, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja, R.N.; Margalef, L. Learning from Dilemmas: Teacher Professional Development through Collaborative Action and Reflection. Teach. Teach. 2013, 19, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P.; Mathew, P.; Peechattu, P.J. Reflective Practices: A Means to Teacher Development. Asia Pac. J. Contemp. Educ. Commun. Technol. (APJCECT) 2017, 3, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Special Education and Speech Therapy. 2018. Available online: https://www.aikos.smm.lt/registrai/studiju-programos/_layouts/15/asw.aikos.registersearch/objectformresult.aspx?o=prog&f=prog&key=4148&pt=of (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Dėl Specialiosios Pedagoginės Pagalbos Asmeniui Iki 21 Metų Teikimo Ir Kvalifikacinių Reikalavimų Nustatymo Šios Pagalbos Teikėjams Tvarkos Aprašo Patvirtinimo. 2011. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.403927/qJrWBSSBCu (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Kirch, S.; Bargerhuff, M.; Cowan, H.; Wheatly, M. Reflections of Educators in Pursuit of Inclusive Science Classrooms. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2007, 18, 663–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.; James, R. An Investigation on the Impact of a Guided Reflection Technique in Service-Learning Courses to Prepare Special Educators. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2007, 30, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, N.; Rouse, M. Student Teachers’ Attitudes and Beliefs about Inclusion and Inclusive Practice. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2011, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causarano, A. Becoming a Special Education Teacher: Journey or Maze? Reflective Pract. Int. Multidiscip. Perspect. 2011, 12, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, K.; Somma, M.; Bennett, S.; Gallagher, T.L. Moving Toward Inclusion: Inclusion Coaches’ Reflections and Discussions in Supporting Educators in Practice. Except. Educ. Int. 2015, 25, 55–73. Available online: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/eei/vol25/iss3/4 (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Fisher, T.; Somerton, J. Reflection on Action: The Process of Helping Social Work Students to Develop their Use of Theory in Practice. Soc. Work Educ. 2000, 19, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcilroy, D.; Todd, V.; Palmer-Conn, S.; Poole, K. Students’ Self-Reflections on their Personality Scores Applied to the Processes of Learning and Achievement. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2016, 15, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Chen, H.T.; Lin, H.S.; Hong, Z.R. The Effects of College Students’ Positive Thinking, Learning Motivation and Self-regulation through a Self-reflection Intervention in Taiwan. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, J.; Distad, L.; Germundsen, R. Reflective Practice Groups in Teacher Induction: Building Professional Community via Experiential Knowledge. Education 1998, 118, 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bulpitt, J.; Martin, P.J. Learning about Reflection from the Student. Act. Learn. Higher Educ. 2005, 6, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, N.M. Reflection as dialogue. Br. J. Soc. Work 2007, 37, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Ke, F.; Sharma, P. The Effect of Peer Feedback for Blogging on College Students’ Reflective Learning Processes. Internet Higher Educ. 2008, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet, D. Some Aspects of Collaboration in Inclusive Education–Teachers’ Experiences. CEPS J. 2013, 3, 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kaendler, C.; Wiedmann, M.; Rummel, N.; Spada, H. Teacher Competencies for the Implementation of Collaborative Learning in the Classroom: A Framework and Research Review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 27, 505–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha Le, J.J.; Wubbels, T. Collaborative Learning Practices: Teacher and Student Perceived Obstacles to Effective Student Collaboration. Camb. J. Educ. 2018, 48, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilden, S.; Tikkamäki, K. Reflective Practice as a Fuel for Organizational Learning. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, J.; Hay, A.; Drago, W. The Reflective Learning Continuum: Reflecting on Reflection. J. Market. Educ. 2005, 27, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.C.N.; Souza, T.V.; Oliveira, I.C.S.; Moraes, J.R.M.M.; Aguiar, R.C.B.; Silva, L.F. Theoretical Saturation in Qualitative Research: An Experience Report in Interview with Schoolchildren. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa-Inaty, J. Reflective Writing through the Use of Guiding Questions. Int. J. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 2015, 27, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, A.; Kitto, K.; Bruza, P. Towards the Discovery of Learner Metacognition from Reflective Writing. J. Learn. Anal. 2016, 3, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, S.B.; Sándor, Á.; Goldsmith, R.; Bass, R.; McWilliams, M. Towards reflective writing analytics: Rationale, Methodology and Preliminary Results. J. Learn. Anal. 2017, 4, 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. Learning Journals. A Handbook for Academics, Students and Professional Development; Kogan Page: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra, R. Uses and Benefits of Journal Writing. Promoting Journal Writing in Adult Education. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2001, 90, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoban, G. Using a Reflective Framework to Study Teaching-Learning Relationships. Reflective Pract. 2000, 1, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T. Development of Student Skills in Reflective Writing. Available online: https://nursing-midwifery.tcd.ie/assets/director-staff-edu-dev/pdf/Development-of-Student-Skills-in-Reflective-Writing-TerryKing.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- Thorpe, K. Reflective Learning Journals: From Concept to Practice. Reflective Pract. 2004, 5, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A. A Phenomenological Hermeneutical Method for Researching Lived Experience. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, K. Self-reflection in Reflective Practice: A Note of Caution. Br. J. Soc. Work 2006, 36, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, K.; Daudelin, W. The Role of Reflection in Managerial Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice; Quorum: Westport, CT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Korthagen, F.; Loughran, J.; Lunenberg, M. Teaching Teachers. Studies into the Expertise of Teacher Educators. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swennen, A.; Klink, M. Becoming a Teacher Educator: Theory and Practice for Teacher Educators; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M.A. Practice, Theory and Research in Initial Teacher Education. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 40, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverback, H.R.; Parault, S.J. Pre-service Reading Teacher Efficacy and Tutoring: A Review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 20, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleyan, D.; Eleyan, A. Coaching, Tutoring and Mentoring in the Higher Education as a Solution to Retain Students in their Major and Help Them Achieve Success. In Proceedings of the International Arab Conference on Quality Assurance in Higher Education (IACQA), Amman, Jordan, 10–12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Foong, L.Y.Y.; Nor, M.B.N.; Nolan, A. The Influence of Practicum Supervisors’ Facilitation Styles on Student Teachers’ Reflective Thinking during Collective Reflection. Reflective Pract. Int. Multidiscip. Perspect. 2018, 19, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokking, K.; Leenders, L.; Van Tartwijk, J.; Van Tartwijk, J. From Student to Teacher: Reducing Practice Shock and Early Dropout in the Teaching Profession. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2003, 26, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. A Guide to Teaching Practice; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kiggundu, E.; Nayimuli, S. Teaching Practice: A Make or Break Phase for Student Teachers. South Afr. J. Educ. 2009, 29, 345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Sariçoban, A. Problems encountered by student-teachers during their practicum studies. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Kredl, S.; Kingsley, S. Identity Expectations in Early Childhood Teacher Education: Pre-service Teachers’ Memories of Prior Experiences and Reasons for Entry into the Profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 43, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koross, R. The Student Teachers’ Experiences during Teaching Practice and Its Impact on their Perception of the Teaching Profession. IRA Int. J. Educ. Multidiscip. Stud. 2016, 5, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, M.; Halton, C.; Murphy, M. Reflective Learning in Social Work Education: Scaffolding the Process. Soc. Work Educ. 2001, 20, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockbank, A.; McGill, I.; Beech, N. Reflective Learning in Practice; Gower Publishing: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, M.; Ross, D.; Colón, E.; McCallum, C. Critical Features of Special Education Teacher Preparation: A Comparison with General Teacher Education. J. Spec. Educ. 2005, 38, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn-Stewart, M. From Student to Beginning Teacher: Learning Strengths and Teaching Challenges. Cogent Educ. 2015, 2, 1–18. Available online: https://www.cogentoa.com/article/10.1080/2331186X.2015.1053182.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2018). [CrossRef]

| Theme | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Explanation of behavior and ways of assistance for children | Explanation of children’s behavior and ways of communicating with them. | Explanation of children’s behavior emphasizing the importance of work |

| Explanation of communication with children by encouragement and moral support | ||

| Explanation of main subtleties of practice and ways of behaving with children | ||

| Discussion of tactics of behavior with children | Assistance, foreseeing ways of behavior with children in various situations | |

| Emphasis on ways of assistance for children | Emphasis on ways of necessary assistance for children by encouragement | |

| Foreseeing of ways of assistance for children by discussing | ||

| Promotion of professional resolve | Promotion of conviction to work in one’s profession | Promotion seeking to make sure that the choice of the profession is right by observation |

| Emphasis on the purpose of practice, encouraging to assess one’s choice to study | ||

| Emphasis on professional traits | Emphasis on responsibility and dutifulness | Importance of responsibility and dutifulness, implementing professional roles |

| Promotion of investigative activities | Encouragement to investigate activities | Encouragement to investigate in order to understand |

| Foreseeing difficulties in professional activities | Perception of difficulties in professional activities | Discussion of future professional activities, foreseeing possible difficulties |

| Provision of information about complicated situations in practice | Informing about troubles working with the disabled |

| Theme | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Disclosure of children’s personal characteristic | Informing about children’s personal traits | Assistance with recognizing children’s needs |

| Identification of children’s needs | ||

| Familiarization with children’s personal and family peculiarities | ||

| Provision of knowledge about communication with children | Assistance in communication with children | Informing about individual communication with children |

| Explanation of individual communication with children | Explanation of peculiarities of individual approach to each child | |

| Explanation of organization of activities with children | Presentation of specificity of the activity according to children’s needs | Explanation of peculiarities of special needs of children and specificity of work with them |

| Foreseeing behavior strategies in teaching | Explanation of behavior with disabled children in the teaching process | |

| Explanation of requirements for children according to their needs | Explanation of peculiarities of communication with children: their needs and requirements for them | |

| Transfer of experience, managing situations in communication with children | Transfer of experience of “taming” difficult-to-communicate children through observation | |

| Familiarization with children’s educational process | Sharing experiences about children’s involvement in learning | Advice on how to arouse children’s interest in the subject, allowing to give lessons |

| Informing about the parameters of the educational process | Familiarization with curricula, children and school specificity | |

| Acquisition of knowledge about differentiation of individual tasks | Finding out about peculiarities of tasking for children and communication with children through observed activities | |

| Provision of information about specificity of disability | Provision of knowledge about children’s diseases | Provision of information about diseases inherent in children |

| Provision of knowledge about children’s faculties depending on the disability | Provision of information about children’s faculties, disabilities | |

| Disclosure specificity of the chosen specialty | Presentation of the actual practice situation | Distinguishing of advantages and disadvantages of the chosen specialty |

| Deepening of understanding about the type of work | Development of understanding about difficulty and responsibility of work | |

| Emphasis on moments of the activity | Familiarization with the specificity of work, advising on the future activity | |

| Information about children’s self-feeling and problems | Deepening of understanding of children’s feelings | Explanation of children’s feelings and self-feeling |

| Discussion of children’s problems | Familiarization with children’s learning difficulties | |

| Complexity of performance of the teacher’s professional role | Foreseeing of possible mistakes in practice | Explanation of possible mistakes in the trainee’s activity |

| Performance of the teacher’s role in the actual educational environment | The benefit of practice tasks, perceiving one’s professional role | |

| Plugging in the performance of the teacher’s role in practice | Teacher practitioners’ assistance perceiving positive and difficult moments of the teacher’s role | |

| Promotion of personal motivation for activities | Promotion of plugging in the practical activity context | Encouragement to communicate in order to get to know the complexity of work |

| Promotion of involvement in the activity with children | Encouragement to observe and participate in children’s activities |

| Theme | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Children’s indirect “assistance” | Knowledge of future work | Experiencing of failures through performed work |

| Perception of preconditions for assistance for children | Perception of importance of children’s cognition and provision of assistance for them | |

| Emotional—psychological entrenchment in the profession | Self-entrenchment in the profession due to children’s attachment | |

| Learning to treat children | Understanding of the ways of acting with children in a particular situation | |

| The possibility of implementing practice roles | ||

| Acquisition of skills of communication with children |

| Theme | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of personal readiness | Promotion of evaluation of readiness to work in the chosen profession | Assistance evaluating one’s readiness to become a special educator |

| Reflection on the practical activity by providing feedback | Focus on key moments of practice | Promotion to notice essential moments of activities in practice |

| Reflection on practice | Sharing impressions after practice |

| Theme | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Discussion on performance of the practical activity | Presentation of possibilities and limitations in practice | Explanation of peculiarities of approaching children and providing assistance for them |

| Discussion on activity aims in practice | Finding out and sharing impressions, better understanding one’s further activities | |

| Provision of moral support | Moral support, remaining to study the profession | Encouragement not to quit studies |

| Cooperation through sharing personal experience | Going deep into practice while discussing | Recognition of details while discussing about practice |

| Promotion of imagination, helping to go deep into the role of practice | Sharing previously gained experience during practice |

| Theme | Subtheme 2 | Subtheme 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of the practical activity | Identification of difficulties in professional activities | Foreseeing the course of work and possible difficulties through the observed activity |

| Cognition of practical reality through observation | Cognition of one’s future work by observation | |

| Understanding of children’s behaviour and communication with them in the educational process | ||

| Understanding of tactics of work and behaviour with children | ||

| Understanding of one’s role observing special educators’ activities | ||

| Independent communication with children | Understanding of ways of communicating with children | |

| Systemization of information in practice | Observation of children and analysis by accumulating and recording information. | |

| Cognition of practical reality implementing teaching | Perception of the teacher’s role through activity performance | |

| Solution of problems encountered by children from their given lessons | ||

| Professional development | Curiosity for practice | Demonstration of pro activeness to get to know the specialty. |

| Activeness and personal initiative as a possibility to learn | ||

| Targeted simulation of experienced practitioners’ activity | Understanding of work by observing the teacher’s activities and behaviour | |

| Self-studying | Individual striving to understand | |

| Search for information about children with special needs | ||

| Deepening the understanding of children’s needs | Efforts to take interest in and understand children’s needs | |

| Assistance for children, getting familiar with their diseases and needs | ||

| Solution of problems, implemented by practitioners | Observation of behaviour with children and solved problems | |

| Methodological educational experience | Preparation of educational material | |

| Professional socialization | Identification of oneself with the practical activity | Involvement in pupils’ and teachers’ work, perceiving the aims and tasks of practice |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bubnys, R. A Journey of Self-Reflection in Students’ Perception of Practice and Roles in the Profession. Sustainability 2019, 11, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010194

Bubnys R. A Journey of Self-Reflection in Students’ Perception of Practice and Roles in the Profession. Sustainability. 2019; 11(1):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010194

Chicago/Turabian StyleBubnys, Remigijus. 2019. "A Journey of Self-Reflection in Students’ Perception of Practice and Roles in the Profession" Sustainability 11, no. 1: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010194

APA StyleBubnys, R. (2019). A Journey of Self-Reflection in Students’ Perception of Practice and Roles in the Profession. Sustainability, 11(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010194