Socially-Inclusive Development and Value Creation: How a Composting Project in Galicia (Spain) ‘Hit the Rocks’

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Building Blocks

2.1. Commoning as a Social Practice

2.2. Commoning as Social Innovation

- (i)

- an actor or small group of actors developing a plan (deciding to change their behavior);

- (ii)

- following on from which, other actors, hearing about these ideas or plans, become interested, leading to;

- (iii)

- discussion and negotiations among a wider group of actors, through which ‘the new form of action [gradually] becomes shaped and solidifies’ (p. 58).

2.3. Commoning and Closing Cycles

3. Materials and Methods

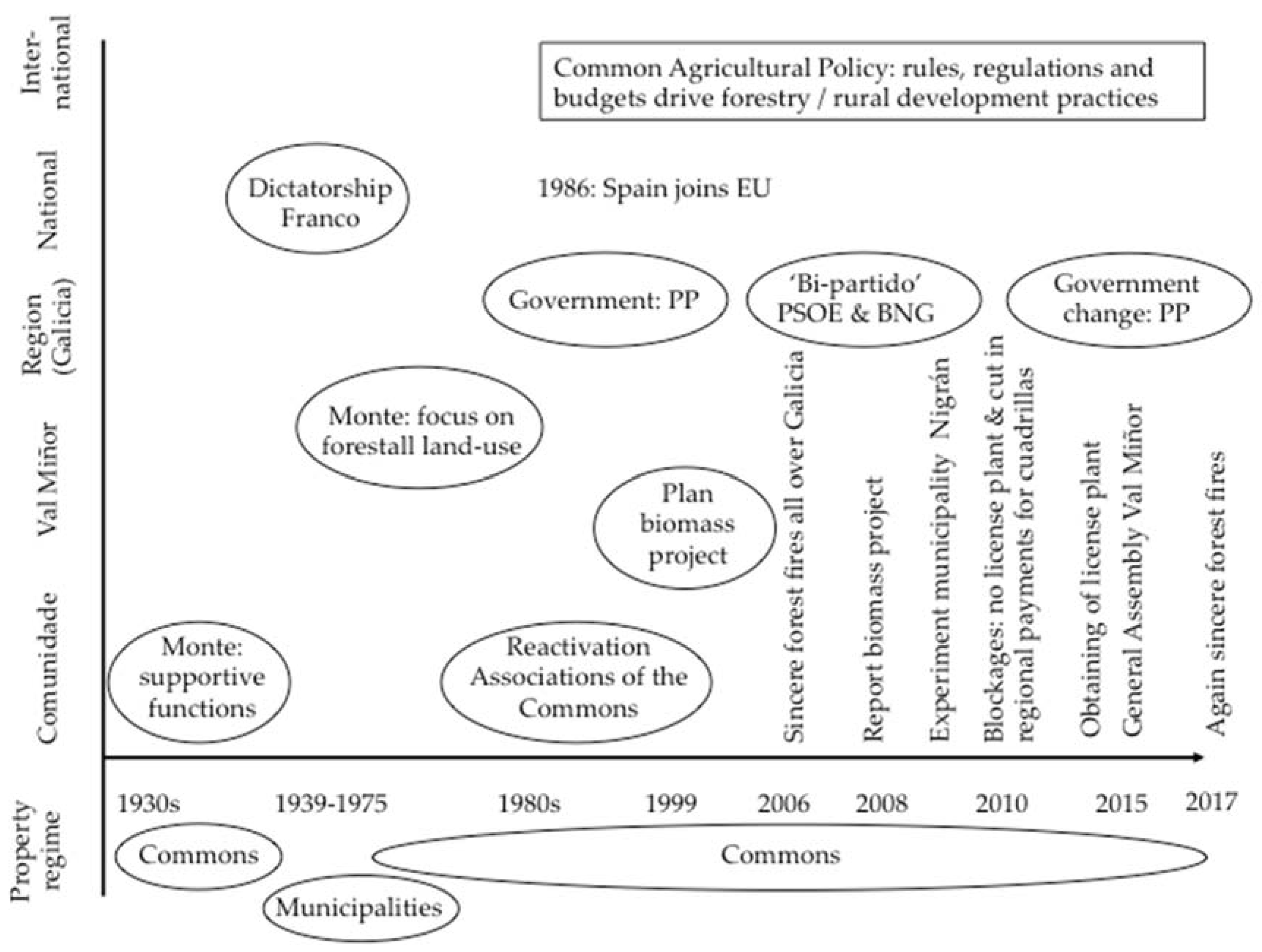

3.1. Communal Management of the Monte

- inalienable, implying that owners can never sell their share, and neither government, nor any other authority, can override this ownership;

- imprescriptible, meaning the owners can never lose their rights to the land, except by expropriation for public needs (such as the construction of roads and hospitals, wind parks or mines, etc.);

- unseizable, meaning neither the government nor a bank can confiscate this land in case of debt, and;

- indivisible, meaning the land cannot be divided and must remain a commonly managed unit with the comuneiros collectively deciding on its management.

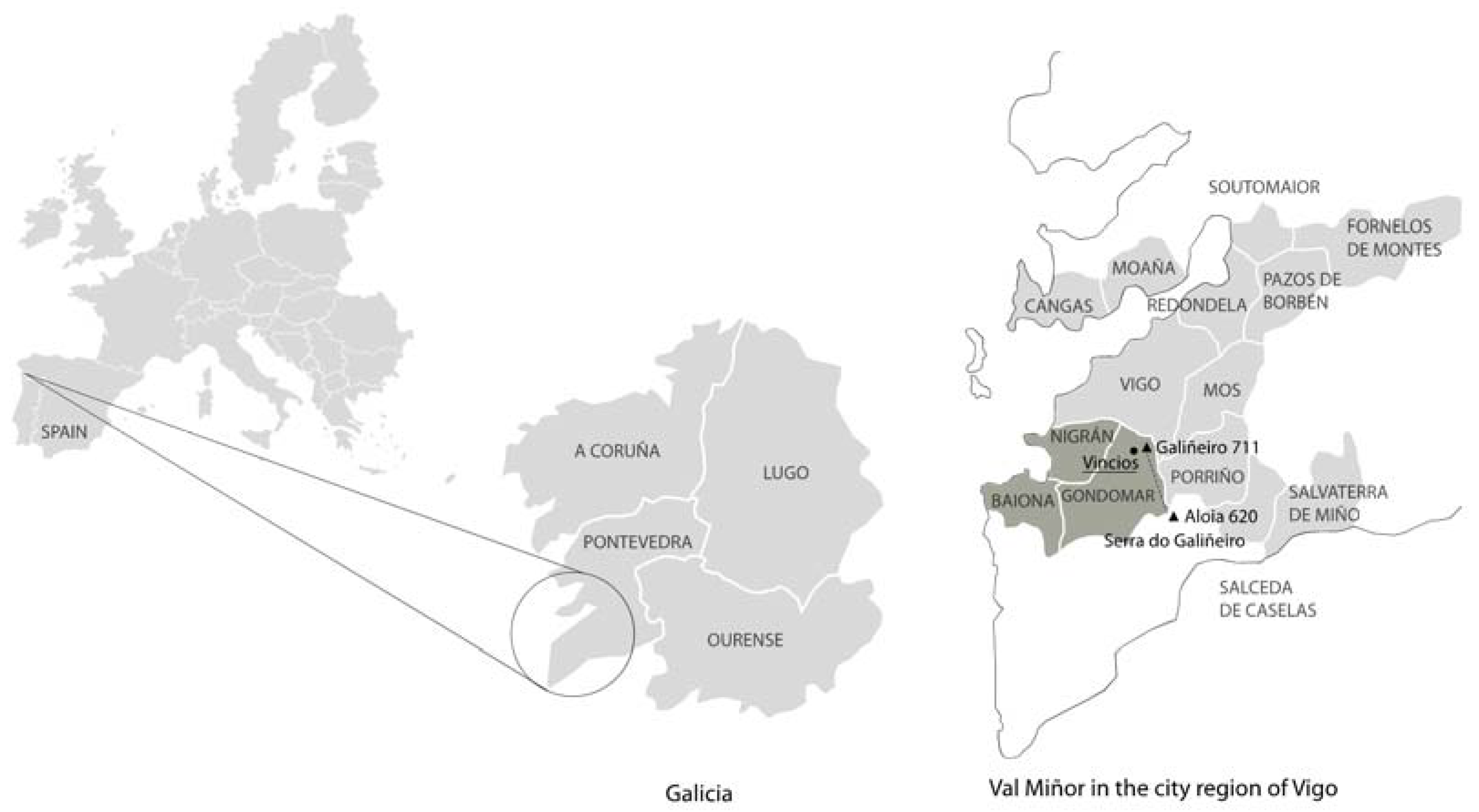

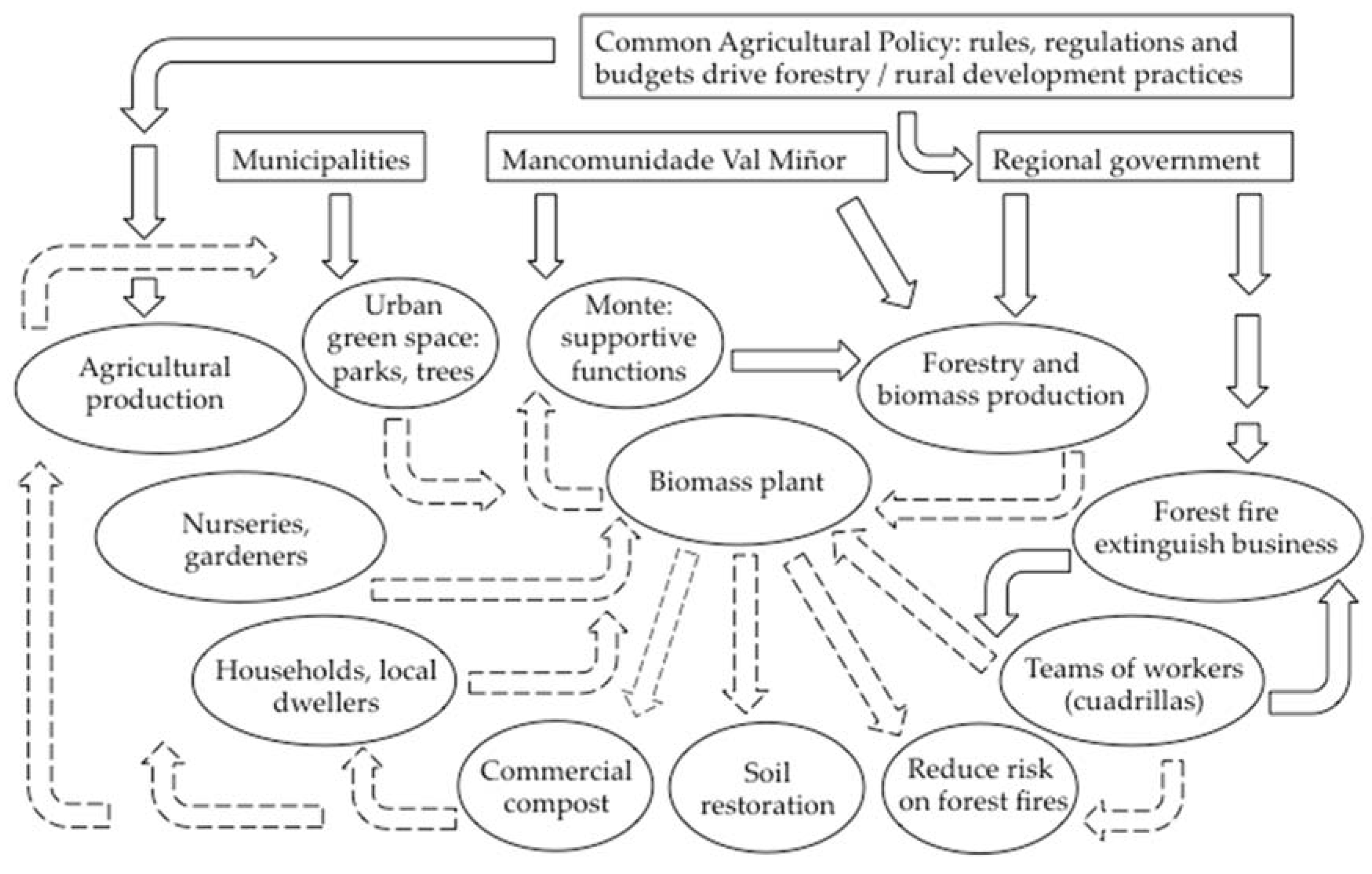

3.2. Upcycling Waste in the City Region of Vigo: The Mancomunidade Val Miñor

3.3. Background and Methodology

4. The Story of the Mancomunidade Val Miñor’s Attempt to Construct a Bio-Composting Plant

4.1. The Management of the Commons

‘Our philosophy, and what we aim to demonstrate, is that the monte is multifunctional, and that it is the comuneiros who have to decide on how to use it. In this organization we provide information and train others, we bring people and ideas together, but nobody is obliged to follow up a proposal. We can make proposals, have ideas, but it is the Comunidade [the local dwellers organized in an Association of the Commons] that has to decide.’

‘It is a democratic system. At least 50% of the membership need to support a proposal at ‘la primera convocatoria’ (the first meeting) and 25–30% in any subsequent meetings. This means that a small group of, say, 5 people cannot manage the monte but that decisions must be quorate. More importantly, there is the right to revocation, which means that if people consider that things are being managed badly they can call for a new meeting. That [opportunity] does not exist at the level of the municipality, nor at the level of the Xunta [the regional government in Galicia] nor at the level of the nation state.’

‘People are not as engaged and participative as they could be. To my mind we talk more within the Xunta rectora [the board of his Association of the Commons] than [the comuneiros in] the assemblea [a meeting of all the comuneiros]. This is a weak point in many places. It is not the case with the Asociación Galega [ORGACCMM, one of the platforms of Associations of the Commons in Galicia], where we do debate things, since all the members of the Asociacion Galega are members of the Xuntas rectoras.’

4.2. Upcycling Solid Organic Waste in Val Miñor

4.3. Building an Actor-Network

‘The value added from the composting plant would benefit the Comunidades de Monte [the Associations of the Commons] and local residents. It would help us to create a living countryside, with the people who live in and from the countryside.’

‘Converting eucalyptus plantations into pastures is not easy because the revenues will be reduced to zero, but we will achieve other goals. The comuneiros understood its relevance and took the decisions to change land-use patterns in our area as they recognized the value of having cattle graze in the area once again.’

‘The biomass project started with the support of the [regional] government. There were the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) and the Bloque (Bloque Nacionalista Galego, a regionalist left-wing party). When the Partido Popular (PP) took over it was all dismantled and we were left without anything. They broke the link between upcycling biomass and the teams of workers in the forest. They disassembled all the Mancomunidades, which can no longer receive subsidies to hire workers.’

‘The idea was to separate the compost into the larger and smaller elements. Our aim was two-fold. First, to promote local employment, and allow the Comunidades de Montes to employ their own teams of workers in the monte. Second: to financially ‘close the loop’ of the work we were doing in the monte. Instead of paying to get rid of the biomass that we were clearing, we wanted to convert it into compost, and use this to improve the degraded parts of the monte, parts lacking organic material or sell to finance the management of the monte.’

4.4. Creating a Value Chain

‘They want biomass to burn and produce energy and to ensure that all of Galicia’s biomass goes to their energy plants. If they had given us permission to start a competing project that conflicted with this then it would have set a precedent and they would not have been able stop others from taking a similar initiative. They didn’t want this type of project to succeed as it would potentially divert biomass from their project. In Val Miñor there are about 3000 hectares that can supply biomass to make compost, which is also of use to them to produce energy.’

‘We initiated the project under a lot of illusions and made large economic investments. The moment that the government had to take the initiative and help bring the project forward we were left completely high and dry. The project turned into a political football. The people in charge of dealing with it had no idea what it was all about at the local level.’

‘When the cuadrillas still existed, we didn’t have permission for the plant and weren’t producing biomass. When the cuadrillas were disbanded we could no longer create the connection between working in the forest and producing biomass, so the plant lost its impetus. […] We already had the machines and, in 2015, wanted to push the project forward, and one of the possibilities was for all the member associations to put in the money to hire the workers. We needed people to transport the biomass from the forest to the plant, crush it, all that type of work […]. The costs of maintaining the plant in combination with the costs for the employing the cuadrillas was too much for the comunidades by themselves.’

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Awareness-Raising

5.2. Collaborative Management and Decision-Making

5.3. Equitable Sharing of Benefits

5.4. Supportive Institutional Environment

5.5. By Way of Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The circular economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B. Shifting from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agudelo-Vera, C.M.; Leduc, W.R.; Mels, A.R.; Rijnaarts, H.H. Harvesting urban resources towards more resilient cities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 64, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart, M.; McDonough, W.; Bollinger, A. Cradle-to-cradle design: Creating healthy emissions—A strategy for eco-effective product and system design. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zeeuw, H.; Drechsel, P. Cities and Agriculture. Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems; Earthscan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hebinck, A.; Vervoort, J.M.; Hebinck, P.; Rutting, L.; Galli, F. Imagining transformative futures: Participatory foresight for food system change. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskerke, J.S.C. On places lost and places regained: Reflections on the alternative food geography and sustainable regional development. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskerke, J.S.C. Urban food systems. In Cities and Agriculture. Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems; de Zeeuw, H., Drechsel, P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bollier, D. Commoning as Transformative Social Paradigm. Esssay for the Next System Project; The Democracy Collaborative: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2016; Available online: https://thenextsystem.org/sites/default/files/2017-08/DavidBollier.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Marsden, T. Third natures? Reconstituting space through place-making strategies for sustainability. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2012, 19, 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- From Waste to Value: The Transition to a Circular Economy. Speech 22 May 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/vella/announcements/waste-value-transition-circular-economy_en (accessed on 5 December 2017).

- Wells, P.; Seitz, M. Business models and closed-loop supply chains: A typology. Supply Chain Manag. 2005, 10, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Or forum the evolution of closed-loop supply chain research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Soleimani, H.; Kannan, D. Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain: A comprehensive review to explore the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste (Waste Framework Directive). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/framework/ (accessed on 6 January 2018).

- MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Cowes, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, First Published 2012. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Schmid, O.; Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Van der Schans, J.W.; Ge, L.; Guyer, C.; Fritschi, R.; Bachmann, S.; Swagemakers, P.; Simón Fernández, X.; López, A.; et al. Deliverable 4.4, Closing of Nutrient, Water and Urban Waste Cycles in Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture. SUPURBFOOD Project, 2015. Available online: www.supurbfood.eu (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Renting, H.; Rossing, W.A.H.; Groot, J.C.J.; van der Ploeg, J.D.; Laurent, C.; Perraud, D.; Stobbelaar, D.J.; van Ittersum, M.K. Exploring multifunctional agriculture: A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swagemakers, P.; Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Onafa Torres, A.; Oostindie, H.; Groot, J.C.J. A values-based approach to exploring synergies between livestock farming and landscape conservation in Galicia (Spain). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraussmann, F.; Schandl, H.; Siferle, R.P. Socio-ecological regime transitions in Austria and the United Kingdom. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duncan, J.; Pascucci, S. Circular solutions for linear problems: Principles for sustainable food futures. Solutions 2016, 7, 58–65. Available online: https://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/article/circular-solutions-linear-problems-principles-sustainable-food-futures/ (accessed on 8 December 2017).

- Ostrom, E. Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivero-Pol, J.L. Food as commons or commodity? Exploring the links between normative valuations and agency in food transition. Sustainability 2017, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundgren, G. Food: From commodity to commons. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Costa, M.R. Food as common and community. Commoner 2007, 12, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Quilligan, J.B. Why distinguish common gooos from public goods? In The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State; Bollier, D., Helfrich, S., Eds.; Levellers Press: Amherst, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 73–81. Available online: http://wealthofthecommons.org/essay/why-distinguish-common-goods-public-goods (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Hardin, G. The tradegy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linebaugh, P. The Magna Carta Manifesto. Liberties and Commons for All; University of California Press: Berkely, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hensen, Z. Sustainable Community Systems: Commoning and Spatial Production. Theory Action 2016, 9, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellbrock, W.; Roep, D.; Mahon, M.; Kairyte, E.; Nienaber, B.; Domínguez García, M.D.; Kriszan, M.; Farrell, M. Arranging public support to unfold collaborative modes of governance in rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongerden, J.; Swagemakers, P.; Barthel, S. Connective storylines: A relational approach to the design and management of urban green infrastructures. Span. J. Rural Dev. 2014, 5, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C.; Smits, R.; Klein Woolthuis, R. Learning towards system innovation: Evaluating a systemic instrument. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bock, B.B. Social innovation and sustainability; how to disentangle the buzzword and its application in the field of agriculture and rural development. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2012, 114, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Voβ, J.P.; Grin, J. Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskerke, J.S.C.; Bock, B.B.; Stuiver, M.; Renting, H. Environmental co-operatives as a new mode of rural governance. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 2003, 51, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Mettepenningen, E.; Swagemakers, P.; Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Jahrl, I.; Koopmans, M.E. The challenges of governing urban food production across four European city-regions: Identity, sustainability and governance. Urban Agric. Reg. Food Syst. 2018, 3, 160006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C. Settling shared uncertainties: Local partnerships between producers and consumers. Sociol. Rural. 2005, 45, 324–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Martinelli, F.; Swyngedouw, E.; Gonzalez, S. Towards alternative model(s) of local innovation. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1969–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rip, A.; Kemp, R. Technological change. In Human Choice and Climate Change; Rayner, S., Malone, E.L., Eds.; Battelle Prêss: Colombus, OH, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 327–399. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeier, S. Why do do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research? —Proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M. Disintegrated rural development? Neo-endogenous rural development, planning and place-Shaping in diffused power contexts. Sociol. Rural. 2010, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratesi, U.; Perucca, G. Territorial Capital and the Effectiveness of Cohesion Policies: An Assessment for CEE Regions. Investig. Reg. 2014, 29, 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Swagemakers, P.; Copena Rodríguez, D.; Domínguez García, M.D.; Simón Fernández, X. Fighting for a future: An actor-oriented planning approach to landscape preservation in Galicia. Dan. J. Geogr. 2014, 114, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. Diverse economies: Performative practices for ‘other worlds’. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Schot, J.; Hoogma, R. Regime shifts through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1998, 10, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilderer, P.; Schreff, D. Decentralized and centralized wastewater management: A challenge for technology developers. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Leverenz, H. The rationale for decentralization of wastewater infrastructure. In Source Separation and Decentralization for Wastewater Management; Larsen, T.A., Udert, K.M., Lienert, J., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Brunori, G.; Galli, F. Sustainability of local and global food chains: Introduction to the special issue. Sustainability 2016, 8, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. Mobilizing the regional eco-economy: Evolving webs of agri-food and rural development in the UK. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Linking Social and Ecological Systems for Resilience and Sustainability: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostindie, H. Unpacking Dutch multifunctional agrarian pathways as processes of peasantisation and agrarianisation. J. Rural Stud. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, H.A.C.; Melman, T.C.P.; Boonstra, F.G.; Erisman, J.W.; Horlings, L.G.; De Snoo, G.R.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Wassen, M.J.; Westerink, J.; Arts, B.J.M. Promoting nature conservation by Dutch farmers: A governance perspective. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 15, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez García, M.D.; Swagemakers, P.; Copena Rodríguez, D.; Covelo Alonso, J.; Simón Fernández, X. Collective agency and collaborative governance in managing the commons: The case of “A Serra do Galiñeiro” in Galicia, Spain. Span. J. Rural Dev. 2014, 5, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Simón Fernández, X.; Swagemakers, P. Edible landscape: Food and services from common-land use in the Vigo city region. Urban Agric. Mag. 2015, 29, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel, S.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Social-Ecological Memory in Urban Gardens—Retaining the capacity for management of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.; Parker, J.; Ernstson, H. Food and green space in cities: A resilience lens on gardens and urban environmental movements. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1321–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S. The potential of ‘Urban Green Commons’ in the resilience building of cities. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, D. Community, institutions and environment in conflicts over commons in Galicia, Northwest Spain (18th–20th centuries). Int. J. Strikes Soc. Confl. 2014, 5, 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhier, A. La Galice. Essai Géographique D’analyse et D’interprétation d’un Vieux Complexe Agraire; Imprimerie Yonnaise: La-Roche-sur-Yon, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, D. Conflicto ambiental, transformaciones productivas y cambio institucional. Los comunales de Galicia (España) durante la transición a la democracia. Hist. Ambient. Latinoam. Caribeña 2016, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Marey Pérez, M.F.; Crecente Maseda, R.; Rodríguez Vicente, V. Claves para comprender los usos del monte en Galicia (España) en el siglo XX. In Proceedings of the 2nd Latin American Symposium on Forest Management and Economics, Barcelona Spain, 18–20 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, G. Community-based forest management institutions in the Galician communal forests: A new institutional approach. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 50, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consulta CC 30/2017. Comité de Flora y Fauna Silvestres. Comité Científico del Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. Available online: http://praza.gal/xornal/uploads/dictamen_comite_cientifcio_eucalyptus-dec2017.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2018).

- Fernández Leiceaga, X.; Iglesias, E.L.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Rodríguez, B.B.; Outeiriño, P.V.; López, X.L.B.; Prieto, L.F.; Fernández, D.S. Os Montes Veciñais en Man Común: O Patrimonio Silente. Natureza, Economía, Identidade e Democracia na Galicia Rural; Edicioìns Xerais de Galicia: Vigo, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Soto, D. From an “integrated” to a “dismantled” landscape. In The Economic Value of Landscapes; Van der Heide, M., Van der Heijman, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 204–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Copena, D.; Swagemakers, P.; Simón Fernández, X. The Metropolitan Area of Vigo in the Northwestern Part of Spain. Deliverable 2.2, Work Package 2. SUPURBFOOD Project. 2013. Available online: www.supurbfood.eu (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Kurtz, C. Working with Stories in Your Community or Organization. Participatory Narrative Inquiry; Kurtz-Fernhout Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.workingwithstories.org (accessed on 14 January 2016).

- Vanclay, F. Guidance for the Design of Qualitative Study Evaluation; A Short Report to DG Regio; Department of Cultural Geography, University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- López, A.; et al. Compostaxe: Prevención e Restauración. Informe Annual 2008 (Composting: Prevention and Restoration. Annual Report 2008); Organización Galega de Montes Veciñais en Man Común, Mancomunidade de Montes Veciñais en Man Común de Val Miñor, Universidade de Vigo: Vigo, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, P.; Rotmans, J. Integrated sustainability assessment: What is it, why do it and how? Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 1, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J. Tools for integrated sustainability assessment: A two-track approach. Integr. Assess. 2006, 6, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Swagemakers, P.; Simón Fernández, X. Deliverable 8.3, City-Region Workshops. Stakeholder Meetings in SUPURBFOOD’s City-Regions. SUPURBFOOD Project, 2013. Available online: www.supurbfood.eu (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Swagemakers, P.; Simón Fernández, X.; Koopmans, M.; Mettepenningen, E.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Kunda, I.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Grīviņš, M.; Reed, M.; et al. Deliverable 8.7, 2nd City-region Workshops Report. SUPURBFOOD Project, 2015. Available online: www.supurbfood.eu (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Swagemakers, P.; Hegger, E.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. Summary Report. In Proceedings of the SUPURBFOOD 1st International Seminar, Vigo, Spain, 26–27 June 2013; SUPURBFOOD Project, 2013. Available online: www.supurbfood.eu (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Swagemakers, P.; Dubbeling, M.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. ICLEI Resilient Cities 2015. In Proceedings of the Urban Food Forum/Second SUPURBFOOD International Seminar, Bonn, Germany, 10 June 2015; SUPURBFOOD Project, 2015. Available online: www.supurbfood.eu (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Turner, S.F.; Cardinal, L.B.; Burton, R.M. Research design for mixed methods: A triangulation-based framework and roadmap. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonos Lourido. Available online: http://abonoslourido.com/es/ (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- What Is a Circular Economy? Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2010. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy (accessed on 6 January 2018).

- Sandstrom, E.; Ekman, A.K.; Lindholm, K.J. Commoning in the periphery—The role of the commons for understanding rural continuities and change. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, J.M.; Iriarte-Goñi, I. Commons and the legacy of the past. Regulation and uses of common lands in twentieth century Spain. Int. J. Commons 2015, 9, 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofie, O.; Jackson, L. Deliverable 3.2, Thematic Paper 1: Innovative Experiences with the Reuse of Organic Wastes and Wastewater in (peri-) Urban Agriculture in the Global South. SUPURBFOOD Project, 2013. Available online: http://www.supurbfood.eu/scripts/document.php?id=71 (accessed on 7 January 2018).

- Wiskerke, J.S.C.; Verhoeven, S. Flourishing Foodscapes: Socio-Spatial Design Principles for Regenerative City Region Food Systems; Valiz: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Pena, M. O Comité Científico do Ministerio Resolve que o Eucalipto é Unha Especie Invasora e Recomenda a Súa Erradicación. Praza Pública, 2018. Available online: http://praza.gal/movementos-sociais/16397/o-comite-cientifico-do-ministerio-resolve-que-o-eucalipto-e-unha-especie-invasora-e-recomenda-a-sua-erradicacion/ (accessed on 6 April 2018).

- Ansede, M. El Gobierno Rechaza Clasificar el Eucalipto Como Especie Invasora. El País, 2018. Available online: https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/04/04/ciencia/1522857047_252833.html (accessed on 6 April 2018).

- Copena, D.; Simón, X. La produccion de energia electrica a partir de la biomasa forestal primaria: Analisis del caso gallego. Revista Galega de Economía 2014, 23, 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, X.; Copena, D. Eolic energy and rural development: An analysis for Galicia. Span. J. Rural Dev. 2012, 1, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón Fernández, X.; Copena Rodríguez, D. Enerxía Eólica en Galicia: O Seu Impacto no Medio Rural [Wind Energy in Galicia: Its Impact on the Countryside]; Universidade de Vigo, Servizo de Publicacións: Vigo, Spain, 2013. (In Galician) [Google Scholar]

| Role of Actors | Number of Interviews |

|---|---|

| Comuneiros (commoners) | 7 |

| Food shop entrepreneurs | 2 |

| Consumer group coordinators | 1 |

| Horticulturists with home delivery | 4 |

| Vegetable nursery entrepreneur | 1 |

| Compost producer | 1 |

| Forest technician | 1 |

| Coordinator market local food products | 1 |

| Representative of local administration | 1 |

| Alderman | 3 |

| Mayor | 1 |

| Activists/consumers | 2 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Swagemakers, P.; Dominguez Garcia, M.D.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. Socially-Inclusive Development and Value Creation: How a Composting Project in Galicia (Spain) ‘Hit the Rocks’. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062040

Swagemakers P, Dominguez Garcia MD, Wiskerke JSC. Socially-Inclusive Development and Value Creation: How a Composting Project in Galicia (Spain) ‘Hit the Rocks’. Sustainability. 2018; 10(6):2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062040

Chicago/Turabian StyleSwagemakers, Paul, Maria Dolores Dominguez Garcia, and Johannes S. C. Wiskerke. 2018. "Socially-Inclusive Development and Value Creation: How a Composting Project in Galicia (Spain) ‘Hit the Rocks’" Sustainability 10, no. 6: 2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062040

APA StyleSwagemakers, P., Dominguez Garcia, M. D., & Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2018). Socially-Inclusive Development and Value Creation: How a Composting Project in Galicia (Spain) ‘Hit the Rocks’. Sustainability, 10(6), 2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062040