1. Introduction

In its more than five-thousand-year history, China has seen constant changes of its dynasties. Despite a few military coups and internal splits in the inner circles of the royal families, most of these dynasties saw an end to their rule upon losing popular support [

1] (pp. 497, 523, 536). Peasant uprisings, instead, ousted the incumbents and inaugurated their own revolutionary heroes into office. This repeated practice of failed regimes overthrown by groups of disgruntled peasants, since the early times of Chinese history, renders ruling legitimacy an essential ingredient for a lasting and thriving reign in China [

2]. Apart from the regular administration of national affairs in the royal palace, the emperors often set out to tour different localities for strategic purposes. For instance, the emperor Qianlong of Qing Dynasty (1711–1799) was known for his diligent but extravagant inspection tours to localities to ensure social stability and popular satisfaction with his governance [

3]. The Emperor Wudi of Han (110 BC) toured the high places on the mountaintops to pay religious tributes to the gods, because an important part of his ruling legitimacy relied upon the popular belief in his heavenly mandated kingship [

4].

In the contemporary China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) conducts inspection tours to boost and maintain public approval. Contemporary government inspections, of course, occur at greater frequencies and with much more proximity to the grassroots than those by ancient emperors. These inspections to localities are intended to police local officials and oversee local governance. Officials in China at all levels are expected to tour areas under their jurisdiction to ensure smooth performance of administrative affairs and proper resolution of local conflicts. Inspections to villages are an important mechanism for the Chinese government to gain legitimacy. However, whether inspections have been effectively utilized for this designated purpose remains less clear. We know very little about how the Chinese government employs inspections to boost its public approval. Are these attempts by higher officials to reach down to localities ever effective in helping the regime stay in power?

Sufficient research has looked into how authoritarian regimes maintains control and prolongs its durability. Traditional literature seeks to outline factors that determine regime survival. The overarching finding of this strand of scholarship is that political institutions, institutions of power succession and political coalition, account for longer regime longevity [

5,

6]. Authoritarian regimes resilient in adapting their structures and efficient in purging political oppositions tend to last longer than those without these credentials. But few have focused upon how the daily governance conducted by different authoritarian leaders on the ground actually benefits or harms regime survival. A sustained level of regime legitimacy is not only a function of power plays among political rivals in the royal palaces, but also a result of pragmatic connection to and resonances among the people ruled.

Inquiring into the utility of inspections in gaining the regime ruling legitimacy is important for a number of reasons. First, inspections tours are costly. Unless they are meeting the desired goals, inspections should be kept to a minimum. In ancient China, the emperors’ lavishing tours required that roads stretch along straight lines, resting stations be constructed to sizes and scale comparable to the capital’s royal palace [

3]. Though inspection tours in contemporary China is much more cost-effective with faster transportation and advanced tele-communication facilities, officials still have to sacrifice valuable time and energy to visit localities. Especially inspections by high-profile officials, such as the premier, take immense administrative resources and cause much disruption to local citizens’ lives.

Second, to the extent that inspections do help the Chinese regime advance its political agenda, understanding the political efficacy of inspections provides us with a unique window to assess authoritarian governance in China. While political institutions are an important variable in evaluating any given polity, how well the administration governs with these institutions is perhaps more important. Chinese history offers the most telling evidence. From the Tang (618–907) through the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the political institutions, including the extensive bureaucracy, expanded while the dynasties have changed from one to another, indicating that how well a dynasty performs is related to how it has utilized political institutions for its favor. Historians attribute the failure of these dynasties mostly to incapable and irresponsive governance [

2].

In this paper, I examine how visits by higher-level officials to villages reinforce the ruling legitimacy of the Chinese regime. Specifically, this study delves into how inspections improve public approval of the village leadership. If inspections help increase popular opinion of the leadership among villagers, they serve the CCP’s best interest in enhancing its ruling legitimacy. I contend that inspection tours to Chinese villages significantly boost the public approval of village leaderships by promoting the governing efficacy of village leaders. This causal relationship holds, first, by improving village social welfare and economic development, and second, by securing for village leaders essential political and financial support from higher authorities to better represent villagers’ interests and mediate conflicts among villagers. Using data of 961 randomly selected villages across China, the empirical analysis shows that Chinese government inspections significantly boost villagers’ approval regarding their village leaders. In the following, I first present the theoretical argument of how Chinese government inspections improve ruling legitimacy of the Chinese regime. Second, empirical analysis tests the theory with multivariate regression models. The study then concludes with a discussion of findings from the analysis and discussion on the future directions of relevant research topics.

2. Theory

Government inspections improve popular legitimacy of the village leadership, first and foremost, through enhancing its governing efficacy. In a comprehensive study of county level governments, the Chinese scholar, Liu Tianxu, argues that Chinese government inspections bring salient improvement to village governance [

7] (p. 117). Governance improves mainly through timely enforcement of relevant policies and resolving challenges in a timely manner. Inspections serve as one of the most important avenues of policy implementation for the Chinese government. While sometimes abused by politicians to collect illegitimate fees and obtain personal gains, most inspections do bring forth considerable improvement in local governance. My fieldwork also confirms the noticeable utility of inspections in village governance. Most government officials I interviewed agree that government inspections, while flawed in many ways, are useful for bolstering the unity of the village leadership and checking behaviors of village leaders. News stories also abound about visits of the central government officials, especially the president or the premier, have prompted immediate actions of local officials to better people’s livelihood in those inspected areas. The higher the authorities that conduct inspections, the more coverage by TV and online news networks the inspection attracts. In particular, the central government officials and provincial governors do well in publicizing their political activities.

The improvement comes both before and after inspections. Before-inspection improvement is mainly a result of preemptive measures by local officials to ensure a good “image” in front of their superiors prior to inspections. Before inspections arrive, local officials are usually on the alert to present competent governance to their superiors in order to secure and promote their positions [

7] (p. 117), [

8] (p. 89). To put smiles on the inspecting superiors’ faces, local officials, often notified “hinted” about the impending inspection, invest extensively on areas under their jurisdiction where the “big figures” are most likely to arrive. For instance, in December 2012, knowing that former Premier Wen Jiabao was about to visit their county but unaware of which specific village in that county, local officials in Huanxian County, northwest China, selectively furnished the residence infrastructure of a couple households that, in their opinion, Wen was most likely to inspect. It turned out that Wen only went to only one of them. Liu Tianxu also reports similar alerted actions by local officials: faking local development by particularly beautifying places where inspecting officials would visit [

7] (p. 118).

Interviews in northwest China also reveal that inspections give incentives to local officials to interact more with village leaders to familiarize themselves with village development when their superiors inspect. Curious about local development, inspecting officials tend to ask local villagers, as well as officials, whether certain projects are being built, if villagers are receiving granted benefits. Local officials have to make sure they are well-informed of local situations and appear knowledgeable in front of their superiors. Furthermore, inspections encourage better interactions between village leaders and local officials, because local officials seek to build trusting relationships with village leaders and eliminate “negative reports” that could potentially arise to tarnish their superiors’ impression of them and worse, even endanger their entire political career. The most popular question these officials ask is regarding the welfare of the people. They do express interest in local stability and conflicts among households as well.

Some of these preemptive actions by local officials can lead to unlawful political detention of disagreeing villagers. For example, to keep potential complaints in Gaozhaigou Village in northwest China (even protests) from reaching the arriving provincial Director of Organization Department, Wu Degang, in 2016, local officials at Huanxian County had started mobilizing public security departments of the county government to isolate the dissenting peasants (diaomin) in Gaozhaigou Village before Wu’s final arrival.

With high levels of job security and lucrative benefits, official positions in the government are highly sought. Local officials are unlikely to lay back when their superiors are inspecting localities under their jurisdiction. While such announced inspections might expose higher authorities to false information regarding local development, they are still useful in terms of inciting more swift actions by local governments to get things done.

What is more significant is that the local government actions motivated by impending inspections tend to last for a considerable period of time. For instance, the same village in Huanxian County that the former Premier Wen visited in 2012, Gaozhaigou, has become the focal point for pilot projects that the Chinese government intends to initiate. It was selected as one of the Pinpointed Poverty-relief (PP) (jingzhunfupin) villages. Hong Mingyong argues that the PP project and its underpinning doctrine was first mentioned in Xi’s inspection tour to Hunan province in November 2013 and then later matured into a systematic anti-poverty methodology and ideology [

9,

10]. The goal of this project is to make pointed efforts to meet the local needs for development and for poverty relief. These efforts include concentrated financial and commercial assistance to impoverished areas to facilitate economic development. The first step in this project is to clearly identify poor households and then employ individually tailored strategies to improve the well-being of each. As a pioneer in the execution of this project, Guangdong province has built “poverty” profiles for 367,000 houses in as many as 3407 villages. In addition, the province has budgeted almost 23 billion RMB (about 3.4 US dollars) financial support and stationed 11,524 government cadres in 3541 groups into villages to keep in direct sight the process.

The PP project assigns a particular provincial department to minister the given village’s development. The provincial department overseeing Gaozhaogou is the Organization Department of Gansu Province. The constant arrival of the departmental head, Wu Degang, at Gaozhaogou has induced a sustained influx of government support grants since 2015. Similarly, the Lankao County, for which the Party icon, Jiao Yulu, was the former party secretary (1962–1964), is also a pilot district for the PP project. The Chinese state media, people.com.cn, has pledged multimedia support for Lankao during this process by setting up a special column to track the progress of the PP project in that county [

11]. Lankao county has been visited by every Chinese president since Deng, for its former governor, Jiao Yulu, has set a laudable example for the CCP of reaching out to the grassroots by being among them. Such concentrated, high-profile support from a state media like

renminwang is unprecedented. The site reports an invigorated dynamic of the flourishing economy in Lankao.

Government inspections favor village governance by immediately impacting village leaders in more personal ways as well. Inspections empower village leaders to properly implement state policies and offer them essential leverage to settle village disputes. That village leaders usually accompany higher officials during inspections conveys to villagers the authority’s consent and support of this village leadership. In the Chinese hierarchy, inspections by higher authorities are usually accompanied by government leaders at lower ranks. For instance, President Xi Jinping’s inspection tours to localities are almost invariably accompanied by provincial leaders of the locality’s province, and municipal leaders of the locality’s municipality. The same is true for inspections by every other level of government. Thus, this framing effect of inspections on village leaders as the legitimate and recognized government representatives earns village leadership popular obedience. More practically, village leaders can appeal to inspection officials for bureaucratic and financial assistance to overcome governing difficulties in their villages. A bureaucratically and financially equipped village leadership thus enjoys much more efficient village governance.

Government inspections can help provide legitimacy to village leadership in a structural context where village leaders possess little autonomy from local government, where they usually work passively under orders from the local government, and where they are deprived of resources and political clout. Government inspections significantly shift the power balance between village leadership and local governments. Inspections entail more autonomy for village leaders.

First, in a country where officials in prestigious and powerful positions are usually less available to the masses, inspections bring to villages the otherwise unreachable and unavailable officials from local governments so that villagers and village leaders can now appeal their grievances to higher authorities at more convenience. Inspections are an important channel for village leaders to articulate to higher authorities the challenges they face in their positions, gaining sympathy both from higher authorities and from the villagers. Petitioning villagers’ grievances to higher authorities, as a result, becomes more effective where inspections are more frequent, because inspections make high governments available to them. By contrast, without inspections, making villagers’ voices heard by higher authorities becomes a more painstaking process. Denied channels of expression, a trivial grievance can spiral into uncontrollable extrajudicial actions, such as mass protests and even riots.

The New York Times recently reported that a Chinese villager, Jia Jinglong, killed his village leader, He Jianhua, after he appealed, unsuccessfully to local officials for two years the unwanted demolition of his three-story house, which led to his fiancée leaving him just a couple days before their wedding. Local officials, however, were simply not available for him [

12]. Many similar cases fuel protests of massive scales. Government inspection exposes and addresses social grievances in a timely fashion by making higher authorities available to receive village leaders’ input. Good-hearted village leaders usually find it hard to persuade the local government to address villagers’ concerns. In front of inspecting superiors, local officials are unlikely to remain indifferent to village leaders’ appeals.

Second, inspections may significantly alter the power balance between village leaders and local governments. Inspections interrupt collusion practices between village leaders and local officials prevalent in rural China. Inspections push village leaders to conduct village affairs in a more professional fashion according to the guidelines issued by the Party. They are thus more effective in settling villagers’ central concerns. In addition, inspections bring village leaders back on track of institutionalized politics by releasing them from deference by local officials to whom these village leaders have to subscribe unwillingly. Even when village leaders have the genuine desire to fulfill their leadership role and govern democratically with transparency, they are sometimes suppressed by the local officials to do so. Inspections offers village leaders the courage to work against the wishes of their immediate superiors, particularly the township and county officials.

There is an established record of higher governments distorting central government policies in order to raise more taxes for local government expenses [

13] (pp. 167, 186). For instance, a significant portion of social conflicts in China are caused by inappropriate land confiscation.

The Beijing News reports that Sichuan Province alone in the first half of 2016 tried 108 local government officials who have manipulated compensation policies to underpay affected households during the demolition of these houses and extort the remaining monies into personal pockets [

14]. The arrival of higher officials provides the immediate victims of these distortions—village leaders and villagers alike—with essential political cover to speak truth to (even against) local governments. Essentially, bringing together political actors of all levels, government inspections open a window of “cross-examination” among these actors, limiting the possibility of any level of authority concealing information, repressing their subordinates or harboring corruption. Thus, inspections free village leaders from potential manipulations from higher authorities.

Most Chinese villagers lend more trust to the central government than the local government [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Perceiving the central government as a more authentic arbiter of social justice and pragmatic politics, Chinese villagers believe that inspections conducted by these higher governments effectively constrain colluding practices between village leaders and local officials. During my field research, I frequently heard Chinese villagers questioning, “Why don’t they (higher authorities) just inspect them (village leaders and local officials)? The corrupted (local) officials would have been sent to prison if inspections happen.” Chinese villagers generally have the impression that the higher government is very effective, once it is resolved to accomplishing certain things. “No one can go against the government at heightened times (of inspections)”, as one villager in a village outside Beijing said in 2004 [

19] (p. 119).

While villagers do not necessarily have solid evidence of collusion between local officials and corporate interests (such as companies), such consensus among villagers across China does tell us that higher government inspections considerably weaken local corporatism [

20,

21] and return relevant parties to political roles they originally belong. China is primarily characterized by a close alliance between business entrepreneurs and the state. Involvement with the latter (either in party membership or other forms of engagement) significantly increases the chances for businesses success. This alliance is similarly prevalent in China’s rural areas. Business leaders, as well as village leaders who strive to get rich, seek to build a reliable (or workable) network with the local government. Local leaders should perform their duties in maintaining a judicial and transparent environment for all villages, while village leaders should only function as mediators between villagers and the higher government within the lawful, institutional boundaries. For instance, village leaders are not supposed to align with local officials against another but to play a role of liaison between local government and villagers.

Third, in addition to being available for village leaders to inform on villagers’ plight, government inspections empower village leaders to better govern villages. This is perhaps most pronounced in competently mediated interest conflicts among villagers. These conflicts may range from interpersonal disputes to large-scale group violence. My interviews show that, to pick a village leader, local governments usually consider, among other important things such as personal qualities of fairness and obedience to local governments, whether the person is able to bring under control village disputes.

While some charismatic village leaders may be able to mediate village conflicts effectively through personal clout and persuasiveness, I argue that, all else equal, village leaders of more inspected villages are more capable in conflict mediation than their counterparts in less inspected villages because of the political support these leaders garner from inspections. The most straightforward causality is that government inspections, accompanied by village leaders, indirectly signals to villagers the higher authorities’ recognition of the village leadership, thus legitimizing the village leaders among the villagers. Such power endowment dramatically increases the weight of village leaders’ intervention in village conflicts. Parties to these conflicts are therefore more willing to come to resolutions proposed by these leaders.

Furthermore, village leaders can more successfully reconcile village conflicts because of the economic and political leverage afforded by these inspections. For example, financial assistance may pour into the village collective revenue due to extensive media coverage of a certain high-profile government inspection. The accumulated financial assets have facilitated development of collective enterprises in that village. Increased public goods bring out good words from villagers about the village leadership [

22] (p. 859). In addition, placing a large sum of collective revenue in the hands of the village leaders makes them more important decision makers in village affairs. It is these village leaders who will decide where the collective wealth will be invested and who will be the primary beneficiaries of these investments. Thus, villagers who are parties to a conflict are more likely to yield to the “rulings” of empowered village leaders, because posing oneself as a spoiler in village affairs invites problems in obtaining favor from village leaders in public goods distribution. One of these public goods provisions is nominating a limited number of “poor households” (dibaohu) to higher authorities. Using the decision-making power over which households are to receive government poverty relief grants in a village as a leverage, village leaders can effectively bring conflicts under control. However, when such power has been deprived from village leaders by corrupted local officials, village leaders lose such governing efficacy. Government inspections streamline provision of such poverty relief funds and these funds further empower village leaders. Even in an event where inspections bring no financial benefit, village leaders can always enhance their mediation efficacy by exporting these conflict cases to higher authorities, as inspections make them accessible.

Lastly, inspections turn village leaders into more effective mediators in village conflicts because inspections increase the chances that village leaders get rich first. During my interviews, most village leaders have expressed heartfelt remarks that village leaders who lead better lives than the village average solicit more obedience from villagers. Their opinions on village affairs usually receive the most positive response if they have managed their personal lives well. By contrast, village leaders who can barely make a living have little influence over village politics. At the same time, my interviews also show that, while inspections do not necessarily bring cash into village leaders’ pockets, they do offer a significant information advantage to these leaders to build their business and run a more successful career. The information advantage refers to the valuable counselling tips and market updates that inspections bring. Local officials hold strongly the view that the government is in a much better position in assessing the outside markets and offering insights on the potentials for a village’s development. One village leader told me that one of the benefits of being a village leader, despite their extremely low salary [

23], is that they enjoy this type of information advantage to get ahead and make more money.

Critics might argue that the authoritarian, top-down inspections might backfire by suppressing democratic urges among villagers in China. On the surface, it seems reasonable that, as democratic practices are more conducive to social order and civilian consent [

24,

25,

26], they call into question the utility of government inspections in winning popular support for the Chinese regime. A closer inspection into the reality in China would reveal a rather different story. First, Chinese government inspections occur mostly for welfare purposes, at least nominally, intending to improve the livelihood of local villagers [

27]. As a result, local villagers are unlikely to see visits by higher officials as intrusion into their space of political freedom.

Second, even in villages where democratic elections have matured, these elections are mostly regarded as “benevolence” from the state [

28]. In the season of elections, inspecting officials arrive in villages not to obstruct the electoral processes, but to administer them according to the Organic Law of Villagers’ Committees (OLVC) promulgated in 1987 [

29]. Most of the rural elections were actually initiated by the central government and imposed top-down [

30,

31]. Lastly, democratic appeals in rural China differ quite significantly from those in liberal democracies in the West. Democratic activists in rural China are more keen to effective means of governance and just ways of distributing public goods, than to expansion of individual political rights. Villagers cast their votes mostly based upon the utilitarian reasons of public service [

32]. Thus, those in full embrace of democratic practices in China do not necessarily see themselves at odds with either the inspecting officials or the Chinese regime in Beijing.

Hypothesis 1. Inspections increase public approval of village leaderships.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Qualitative Approach

Field research was conducted in a number of counties on mainland China from 2012 to 2016. In particular, I visited Huanxian County mentioned in this research for five times during this period, on average about once per year. Personal involvement in local affairs allows me to obtain first-hand information on how locals received high-profile government officials, such as the premier, in 2012. Part of the rationale of choosing this locality for my field research is that Huanxian County has become the archetypical target for the grand national poverty-relief strategy in China, which, as a result, invited a large number of government inspections.

I visited the other four counties during my latest field trip in 2016. The address and names of these counties are not identified in this article for the sake of security. I employed the snowball sampling approach to reach my interviewees. I first started the field trip from Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, my undergraduate alma mater, and interviewed students with rural backgrounds and experience of witnessing inspections. Following this first round of interviews with 22 college students, I asked four of them to tour guide me to their hometowns for a more detailed field observation. While at their hometowns, I also conducted interviews with one county level government official, three village leaders and a couple of villagers. As these interviews are conducted against humans, an Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval was obtained from the University of North Texas, US, before the research was carried out.

While the 22 college students may not be the ideal sample in the first place, it is justifiable that their opinions are valuable and thus offers a first step for conducting the current research. First, though they are college students who mainly focus their time on school, their daily interactions with their parents back in their rural hometowns over an extended period of time enable them to construct a holistic view of how government inspections take their effect on rural governance. Second, Chinese government inspections have exhibited a considerably stable pattern over the past decades [

27] (p. 473). This allows college students, though who are nonprofessional scholars, to grasp a reliable understanding of the utility of government inspections in rural governance. The findings of these field trips are mostly presented in the above sections of the paper.

3.2. Empirical Approach

Data for empirical analysis in this study is from the Chinese Household Income Project (CHIP) 2002 [

33]. This dataset collects information on village governance in 961 randomly selected villages across China. Included in the dataset is the number of inspections paid to a given village as well as variables on village leadership. Most importantly, the dataset records public approval rating of the village leadership by villagers in the year 2002.

The dependent variable for this study is Pub_app, public approval of village leadership. Although village leaders are composed of two independent persons—the Party Secretary (zhishu) and the Village Head (cunzhang)—villagers rate their approval of their leaders as one unitary leadership. Pub_app is thus operationalized as an accumulated score of public ratings of three dimensions of village leadership: village leaders’ willingness to stand up for villagers’ interests, village leaders developing the local economy and village leaders mediating village conflicts.

In the first dimension, villagers express their opinion on village leaders’ ability to properly and resolutely present villagers’ causes to higher authorities in cases where there is a conflict of interest between the government and the villagers. Since village leaders serve as the liaison between the government and villagers, villagers sometimes worry that their leaders do not faithfully represent their interests to higher authorities. Instead, villagers are concerned that these leaders might collude with higher officials to extract more fees and taxes and withhold villagers’ government pensions. In each village of the 961 villages, representatives from the ten randomly selected households within each village were asked to rate between 0 and 5 how well “the village cadre stands as a spokesman for the villagers” with 0 as the least and 5 as the most.

This is a salient concern as my fieldwork confirms that there is very limited autonomy for village leaders from township level officials (the next higher level Chinese government). Villagers display a significant level of distrust toward village leaders in terms of the latter’s willingness to stand up for their interests, when these interests are at odds with those of the township government. Most of village leaders’ decisions are highly controlled by local governments. All of the village leaders I have interviewed indicate that their primary goal is not to represent the villagers’ interest in bargaining with the Party, but to govern the villagers on the Party’s behalf.

By contrast, the second dimension refers to the capability of village leaders to foster robust village economies. Village development is an important parameter for both higher authorities and the villagers to evaluate the village leadership. In each of the 961 villages, representatives from ten randomly selected households within each village were asked to rate between 0 and 5 how well “the village cadre makes efforts to help the villagers get rich” with 0 as the lowest rating and 5 as the highest.

The last dimension captures villagers’ opinion on village leaders’ efficiency in mediating conflicting interests among villagers. Being able to effectively settle villager disputes is a very important, if not the only one, role of village leaders. In each of the 961 villages, representatives from ten randomly selected households within each village were asked to rate between 0 and 5 how well “the village cadre mediates the different interests among villagers” with 0 as the lowest rating and 5 as the highest.

The dependent variable is then generated by adding the rating scores of all three dimensions:

where

stand refers to the dimension of village leaders standing up for villagers’ interests,

economy is the degree to which villagers think that their leaders develop the village economy,

mediation measures how well villagers rate their leaders in terms of the leaders’ ability mediate village conflicts. The dataset records individual scores of each dimension. For the purpose of the current analysis, I aggregate them into one value. The normal distribution of

Pub_app is seen in

Figure 1.

The independent variable for all four models is

Insp, average number of county-level or higher government inspections per year (1998–2002). The distribution of

Insp can be found in

Table 1 with descriptive statistics of all relevant variables in this analysis.

The first group of control variables in the model includes three variables measured at the village level:

Income per capita,

Democracy and

Taxre.

Income per capita accounts for the effect that village economic development has on village leaders’ public approval. Village leaders in poorer villages might strive harder to develop village economy and, as a result, their public approval ratings rises. Alternatively, rich villages possess more resources to better mediate village conflicts and bring contentment to villagers, and villagers in richer villages may be more content than their counterparts in less developed villages are. Leaders in villages holding democratic elections arrive at their positions through contested elections. Electoral politics push village leaders in these elected positions to be more transparent and responsive. Thus, I expect

Democracy to have a positive effect on the outcome variable. I expect to see higher public approval for the elected village leadership than for a non-elected one. Finally,

Taxre is also included to control for the potential alienation that the tax reform launched in 2002 has caused between the Chinese government and village leaders. Juan Wang finds that structural fiscal reform has made the Chinese government lose village leaders to the villagers’ side and these village leaders then become key organizers of protests [

34]. The distribution of these control variables can be found in

Table 1.

Besides village-level controls, I also include idiosyncratic characteristics of both the Party Secretary and the Village Head: Age, Education, Exp_mgmt, Exp_busi, Time in office, Salary. The same as its counterparts at higher levels, the village government is also a dual Party-government system with each village government headed by a Party secretary and a village head. Village leaders’ personal profile matters for their diligence in office and thereafter their public approval. Younger village leaders may be more active in their service, simply because they are more energetic and ambitious. However, age may also be a bonus to village leaders in terms of governing efficacy, as older village leaders may wield more influence by seniority in village politics and their experience may make them more effective in their job. Thus older village leaders might enjoy higher public approval. They can be particularly more effective in standing up for villagers’ interests, mediating village disputes, and mobilizing resources for economic development. Education may play a significant part in the leaders’ ability to better articulate complicated situations to their superiors and fellow villagers. Education also endows village leaders with needed temperaments to foster opportunities for commercial activities in villages. Education helps village leaders find creative ways to develop the economy and to abide by law in policy implementation.

Village leaders’ experience in management in a company (Exp_mgmt) or in running a small business (Exp_busi) may increase the odds of an effective village leadership. Experience in management positions or businesses teaches village leaders to strategically deploy limited resources to achieve maximum utility for village governance. Perhaps more importantly, such experience helps village leaders build connections that can later help him/her develop the village economy. Thus, I expect these two control variables to have a strong impact on the leaders’ public approval. Likewise, village leaders’ time in office may also determine how effective they are managing village affairs. Lastly, village leaders’ salary is another important factor in village leadership. Better paid village leaders are freed from concerns of taking second jobs to make a living. They can instead be more focused on village affairs. Public approval, as a result, may increase as village leaders devote more time and energy to village governance.

4. Results

4.1. Model 1

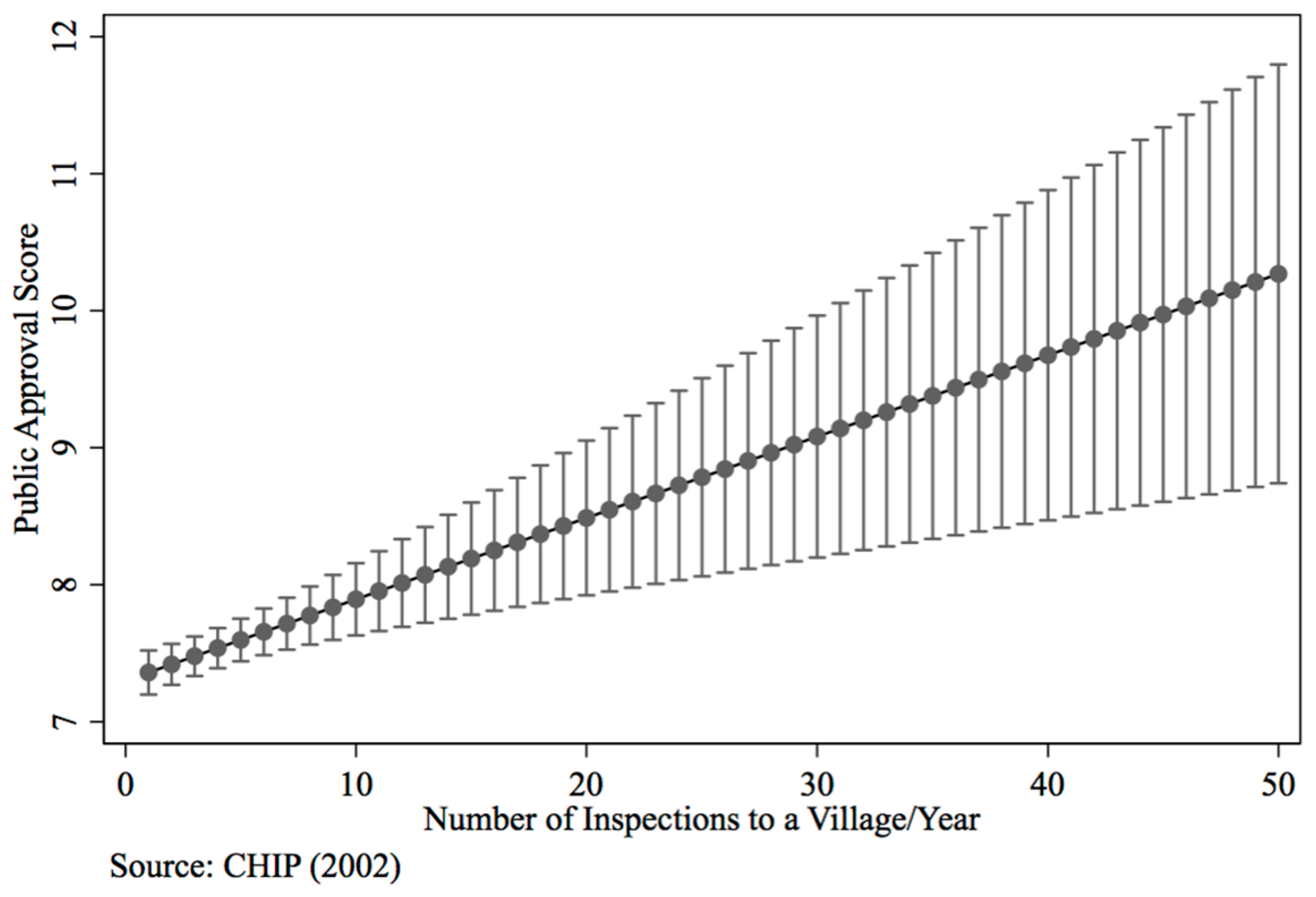

The unit of analysis of this chapter is the village leadership in each village. The number of observations is 794. The village leadership refer to both the village Party secretary and village governor. Given the normal and continuous distribution of the outcome variable, I perform ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Results of this analysis (in

Table 2) show that Chinese government inspections have a positive and statistically significant (

p < 0.01) effect on the dependent variable,

Pub_app, across the four models. This implies that inspections significantly increase village leaders’ public approval. As inspections increase to a village, its leaders enjoy rising public approval among villagers. Substantively, as the frequency of inspections increases from once a year to fifty times a year, the largest value in the dataset, the public approval score of village leaders in this given village is predicted to increase from 7.35 to 10. 27, all else equal (in

Figure 2).

The surprising finding is that, as inspections increase in a village, village leaders are more likely to stand up for the interest of the villagers in the case where villagers’ interest conflict with that of the Party. Intuitively, when the Party’s interests are at stake, the inspecting officials should pressure the village leaders to lean toward the Party, not the opposite. This finding, however, suggests that inspections, with its publicity and influence, release village leaders from local interest groups where village leaders might be enticed by local officials to engage in corruption, or willingly collude with the township officials to extract benefits due the villagers. Such release encourages village leaders to go public and speak for the interests of the villagers. This lends evidence to the argument that village leaders obtain more autonomy upon arrival of higher officials. Granted opportunities to be speak candidly to the higher officials about local grievances, village leaders can now take villagers’ chief concerns to the right personnel.

In addition, a few control variables have also achieved statistical significance in the models. In particular, Income per capita has obtained statistical significance (p < 0.01) in the first model which only includes controls for attributes of the village: its economic development, democratic elections and tax reform. It loses significance, however, when control variables of the characteristics of the Party Secretary are included. It, however, regained significance in the third (p < 0.5) and fourth model (p < 0.1). Economic development in the village appears to be important in weathering villagers’ public opinion on the governing efficacy of the village leadership. As a village becomes richer, the village leadership tends to enjoy a better evaluation from fellow villagers. Substantively, holding all other variables at their mean, as income per capita of a village increases from 1000 RMB (about $147) to 15,000 RMB (about $2205), public approval score of the village leadership increases from 7.32 to 8.9. This makes sense when village leaders, with a considerable amount of resources at their disposal, can make more decisive (and most popular) decisions to better the living conditions of the village. During my fieldwork in China, some village leaders complained that there is little they can do to alleviate the despair in their village and that the poverty has provided the village leadership with little leverage in village politics. Whether a village has held democratic elections does not have any effect on the village leadership’s public approval, a sign of low efficacy of these elections.

The Wald test (Prob > F = 0.0039), giving the comparative weight that each explanatory variable carries relative to others, shows that the core independent variable, Insp, outperforms all the other explanatory variables combined. This indicates the disproportionate significance that this variable of interest carries in the analysis.

Age of the Party secretary and age of the village head have markedly different effects on the outcome variables remains the same in this model. While the age of the village leader has a positive, statistically significant effect on all of the outcome variables, the age of the Party secretary achieves no statistical significance and is in the negative direction. The older a village head is, the higher the approval rating the village leadership as a whole receives, all else equal. The positive effect that village leaders’ experience in business and management positions have on public approval of the village leadership is particularly evident in the case of the Party secretary. It, however, is significantly weaker in the case of the village head.

The above comparison between the control variables of characteristics of the Party secretary and the village head thus reveals that, while business expertise of the Party secretary are much more effective in raising public approval of the leadership, seniority of the village head is more significant in shaping villagers’ views of the leadership. In other words, villagers tend to judge the two village leaders differently in terms of their contribution to the village leadership. Professional credentials of the party secretary, such as experience in businesses, are more appealing to villagers while seniority of the village head appears to be more effective in gaining consent from villagers. This finding reflects the discrepancies in villagers’ perceptual evaluation of the village leadership. Villagers tend to view an older village head plus an experienced party secretary as the most competent partnership in the village leadership. Thus, to select a village leadership that wins the most ruling legitimacy, the CCP should appoint a party secretary who is well-educated and experienced in management and businesses, while helping someone who is older and highly respected in the village get elected as village head.

I am aware of the potential selection bias involved in this analysis. Selection bias refers to the possibility that the Chinese government selectively inspect villages that exhibit higher public approval. If such bias exists, the causal relationship that this analysis identifies could be compromised or even turned to the opposite direction: instead of inspections causing improved public approval, it could be that public approval determines where inspection occurs in the first place. I argue that this selection bias is unlikely because the data used in this analysis captures a significant time lag between inspections and public approval ratings. The independent variable, Insp, is the number of inspections conducted per year during the past three year (1998–2002), while public approval ratings were polled at the time when the survey was conducted, at the end of 2002. Operation of inspections and collection of approval ratings did not happen contemporaneously. As such, this analysis lends convincing evidence to the causal relationship elaborated in the theory section.

Second, even without such time lag between the explanatory variable and the dependent variable, there are few reasons to believe that such selection bias, if any, would challenge the current results. The authoritarian governance under the CCP demands uniform allegiance from all administrative units to support, at least nominally, the regime’s rule. The CCP does not have to avoid “negative villages” to only inspect those in favor of the party. My field research shows that there is a significant level of regime support across villages, especially taking into account the waiver of agricultural taxes since 2004 [

35] and the marked lift of livelihood among the general population. The most likely calculation that the CCP makes in deciding whether to inspect villages supportive or unsupportive of the regime is determined by how the Party strives to ensure its survival. It is unlikely to shun away from areas of trouble. The CCP would most likely prioritize inspections to problematic, not peaceful or supportive, villages to ensure social stability.

4.2. Model 2

In order to parcel out the effects that government inspections have on each dimension of the village leadership (stand up for villagers’ interest, economic development and mediation) and, at the same time, take into account the individual-level characteristics of villagers (Gender, Age, Married, Party_Mem, Minority, Edu and Migrant), I perform a hierarchical model, Ordered Logit regression analysis clustered at the village level. The unit of analysis is individual villager and the number of observations is 7093. An Ordinal Logit model is more appropriate for this analysis, as opposed to the OLS model in the previous examination, because the dependent variables are all ordinal, discrete values from 1 to 5. In conducting the analysis, I also cluster by village to account for the bias caused by village-level control variables (control of villagers, village leaders and villages) in the model.

The core independent variable,

Insp, achieves strong statistical significance (

p < 0.01) in the three models with breakdown of

Pub_app into its specific three dimensions and with controls of idiosyncratic characteristics of villagers (see

Table 3).

Insp continues to have a consistent positive and statistically significant effect on all the dependent variables, implying that, as the number of government inspections to a village per year increases, villagers’ rating of his village leader significantly improves. Government inspections significantly improve villagers’ opinion on their leaders’ governing efficacy in all three aspects: petitioning their causes to higher governments, developing village economy and lastly effectively mediating village conflicts.

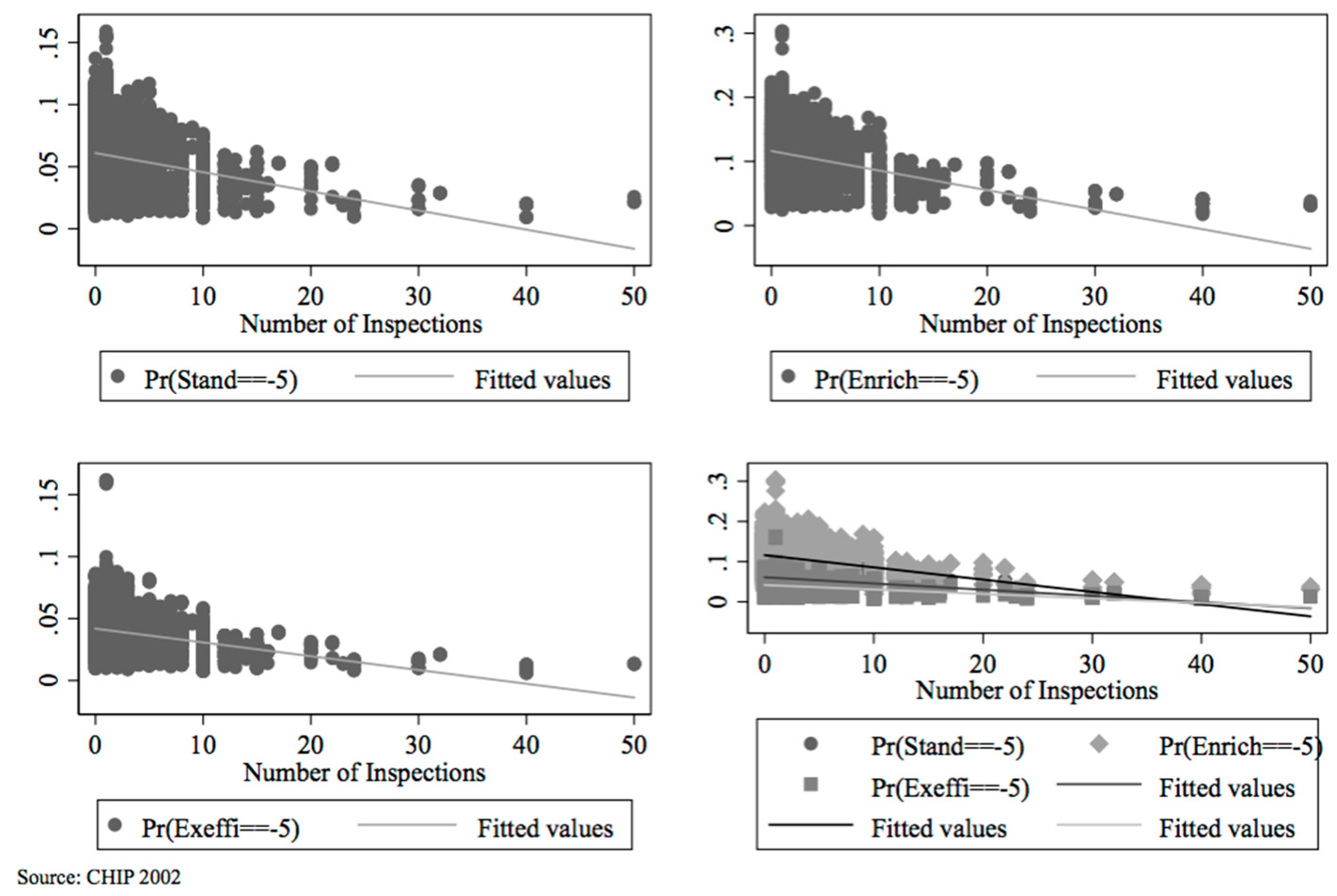

The substantive effects inspections have on public approval rating in its three subcategories appear in

Figure 3. Inspections impact public approval of the village leadership in very similar ways: they help boost the public approval score of village leadership in terms of standing up for peasants’ interests, developing the village economy and mediating village conflicts. However, the effect on public approval of village leaders developing the economy is the strongest among the three (the slope is the steepest in the last chart in

Figure 3). This makes intuitive sense because economic development in the village tends to be the most visible achievement, as peasants’ annual income rises and better infrastructure is being built. This, as a result, can be picked up by villagers more easily than the other two areas of village leadership. The effect that inspections have on the ratings of village leaders’ ability in mediating village conflicts and standing up for villagers’ interests are almost identical (the slopes are almost the same for both graphs).

Some of the control variables in this robustness check have significant impacts on the outcome variables. Economic development continues to exert a positive, statistically significant impact on all three dimensions, confirming my assumption that the economy does matter for the public image of the village leadership and the CCP as a whole. Neither democratic elections nor tax reform plays a significant part in the outcome variable.

Both the Party secretary and the village head’s time in office proves to be a critical factor in winning public approval. The longer they have been in their positions, the higher approval ratings they are likely to receive from fellow villagers, all else equal. This could be a function of the leaders’ familiarity with village affairs: as they serve in office longer, they gain more experience in helping peasants obtain the proper government assistance and fostering relationships among villagers. Education of the Party secretary positively contributes to public approval rating in the areas of developing the economy and mediating village conflicts. Education of the village head, by contrast, does not have any effect on any of the outcome variables.

Lastly, evaluation of the village leadership does not vary significantly over individual characteristics of the villagers. How a given villager rates the village leadership is not dependent upon his gender, age, marital status, education or migrant status. This shows the lack of individualism in Chinese political culture in general and rural political culture in particular. Peasants usually do not form individually unique political beliefs or conviction. Their perspectives on the village leadership are apt to reflect more a communal and general opinion than an individual one. However, a few individual characteristics stand out as significant factors on public approval of the village leadership. The most impressive control is party membership. A villager who is a CCP member views the village leadership much more positively than one who does not belong to the CCP. This is an expected result taking into account the entrenched influence of the CCP in rural areas of China and the conformity of political views that the CCP demands unconditionally from its members.

In addition, minority villagers tend to view the village leadership as more willing to stand up for their interests and develop the village economy, but not necessarily to mediate village conflicts. Aware of its multiethnic population and sensitive to the potential ethnic conflicts in its society, the Chinese government has adopted favorable policies to minority groups. As a result, the village leaders may as well act accordingly to be especially accommodative to minority groups. While villagers who have worked outside the village (Migrant) are indifferent toward the village leadership’s capability to stand up for villagers’ interests and its ability to mediate village conflicts, they tend to view the village leadership’s performance in economic development more negatively than those who do not have migrant work experience. Having seen the extraordinary economic development in urban cities, returning villagers understandably disregard the minimal economic development that their village might have gained.

5. Discussion

This study discusses a unique feature of rural governance in China—government inspections. Via painstaking administrative assignments of official visits to localities, the regime in China manages to connect the extensive official hierarchy to the common masses. Chinese government inspections stand out among other authoritarian states in that they have provided the authorities with essential pathways to build close and concrete relationships with the grassroots. As a result, these administrative endeavors ultimately pay off when the CCP is to reap public support from the very people whom it has elevated out of poverty and protected from social instability.

Both fieldwork and empirical analysis lend strong evidence to the theoretical framework of this study. Chinese government inspections, despite their systematic flaws and occasional superficiality, play an important role in Chinese politics. Diligently touring rural regions of China serves the CCP strategic political interest, as these inspections constantly strengthen the Party’s local foundation and refresh the positive image that the Party has endeavored to construct from its inception. This study argues that Chinese government inspections effectively boost the ruling legitimacy of the Chinese regime. Public approval of village leadership significantly increases as inspections to this village increase, while controlling for other important interfering variables. The institutionalized practice of government inspections in China thus serves as a critical means for sustainable governance in rural China.

Inspections boost the Chinese regime’s ruling legitimacy chiefly by drawing local officials, who may otherwise be far removed from the grassroots, into personal contacts with both villagers and village leaders. Making these officials available to hear appeals from the grassroots alleviate strains between the Party and the people. Effective communication between them not only helps resolve the forthcoming disputes and confusions but also enhances the emotional affinity that the Chinese peasants accords to the CCP’s contribution to the current Chinese state. Moreover, this causal relationship between inspections and improved ruling legitimacy of the CCP exists because inspections alter the power balance between village leaders and local officials, allowing the village leaders to speak boldly to (sometimes against) the inspecting higher officials. Village leaders can now, with less fear of repression from local officials, take grassroots petitions more conveniently and successfully to the right authorities. Inspections also empower village leaders with financial and political leverage to govern village affairs more judiciously and efficiently.

The distinctive cultural values in China provide a helpful context to understand this salient effect that inspections have on the CCP’s approval. China’s cultural values are primarily characterized by obedience to a hierarchical order prescribed by an “unequal distribution of power”, according to Shalom Schwartz’s conception of values [

36] (p. 156). This stands in sharp contrast to the more autonomous and self-expressive cultures most typically represented by the English-speaking world. In addition, according to Ronald Inglehart’s research, despite a fairly low freedom house rating from 1972 through 1997, China obtained a relatively high score on subjective well-being [

37] (p. 227), sitting itself close to South Korea, Spain, and France.

This indicates that, in the contemporary era, the Chinese bid their well-being of happiness more on improved economic development and better living conditions than political freedom and democratic politics. Villagers in China, who are more leaning toward honoring the authorities and feeling indebted to what the CCP accomplishes for the common masses [

38], are more likely to give support to the Chinese regime once in-person visits by high-ranking officials increase.

One of the weaknesses of this research is that the dependent variable is public approval for village leadership, not support for the Chinese regime as a whole. Due to limited data, the current study can only inform us what effect government inspections have upon villagers’ views of their village leaders. Future research, therefore, can delve deeper into the relationship between villagers’ support for village leadership and their support for the CCP. Despite the hypothetical correlation between these two variables, it is interesting to show how immediate approval of the most grassroots government cadres eventually leads to general support for the regime.

Future research can further tap into how the levels of inspecting officials matter in impacting ruling legitimacy. The weight that an inspection by Xi Jinping carries is perhaps much higher than does an inspection conducted by a lower county-level official. More research is also needed in articulating the generalizability of inspection practices in other similar regimes. How can other regimes, such as the Philippines, also learn from Chinese government inspections to institute more regime accountability and responsiveness? Scholars can look at how contacts with legislators affect constituents’ rating of the regime. Lastly, scholars might conduct comparative analysis between authoritarian governance characterized with top-down government interventions and democratic governance where bottom-up elections are more prevalent.

The policy implications for the CCP are mainly that the Party should undertake inspection tours as many as possible to achieve maximum utility. Given the heavy cost of inspections, the Party has to increase the number of inspections, but at the same time keep it below the threshold beyond which their cost outweighs the benefits. It remains another empirical question where this threshold lies. Another important advice for the regime is to pay attention to the make-up of the village leadership. A party secretary who is educated and experienced in business plus a village head who is older and well-respected would make the most promising village leadership. Coopting peasants into the party still remains important as peasants who are party members view the village leadership more positively than those who are not.